Abstract

Extant research on marketing strategy making (MSM) lacks process-based theoretical frameworks that elucidate how marketing strategies are made when sales and marketing functions are involved in the process. Using a grounded theory approach and data collected from (a) 58 depth interviews with sales and marketing professionals and (b) a focus group with 11 marketing professionals, we propose that MSM within the sales-marketing interface is a three-stage, multifaceted process that consists of Groundwork, Transfer and Follow-up stages. Our process-based model explicates the specific activities at each stage that are needed to develop and execute marketing strategies successfully, the sequence in which these activities may unfold, and the role sales and marketing functions may play in the entire process. Managerially, this paper highlights that successful strategy creation and execution requires marketing and sales functions to be equally invested in the entire process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As the two primary revenue generating functions within an organization, sales and marketing should be working together to create and execute successful marketing strategies. This view is held by several scholars who exhort that the sales function be involved in marketing strategy creation, and that both sales and marketing functions synchronize their strategic and tactical activities to create, deliver, and communicate superior customer value (Cespedes 1996; Guenzi and Troilo 2007; Homburg et al. 1999; Rouziès et al. 2005; Slater and Olson 2001).

Yet, evidence from both the academic and trade literature suggests that very often the sales function is not involved in strategy making (Carpenter 1992; Viswanathan and Olson 1992). Rather, in many organizations, strategies are created by marketing without input from sales; the sales personnel are introduced to these new strategies only when their marketing counterparts hand them over for implementation (Kotler et al. 2006). Consequently, many salespeople do not support the strategies marketing develops because they feel these strategies are inappropriate, ineffective, irrelevant, or disconnected from reality (Aberdeen Group 2002; Donath 1999, 2004; Strahle et al. 1996).

An examination of the literature reveals limited insights with respect to the specific roles marketing and sales functions play in creating marketing strategies successfully (cf. Smith 2003 for an extensive review). Further, while scholars studying the sales-marketing interface have stressed the importance of joint involvement of sales and marketing in strategy making, no academic study has explored in depth what such joint involvement entails. Overall, there is a paucity of guiding theoretical frameworks in this area that outline how strategy making within the sales-marketing interface unfolds, and what makes this process more successful. Given that sales and marketing are the primary revenue generating functions for a firm, we wish to delineate the nuances of successful marketing strategy making (henceforth MSM) across the sales-marketing interface, and highlight what may make strategy making more successful within this interface. We do this using the Grounded Theory Approach (Strauss and Corbin 1990, 1998).

Specifically, based on depth interview data from 58 marketing and sales professionals and focus group data from 11 marketing professionals, we propose that MSM across the sales-marketing interface is a three-stage multifaceted process, constituting a continuum of activities that begin at the strategy conceptualization stage and continue through the follow-up stage. Our grounded-theory based model explicates the specific set of activities and processes needed to develop and execute marketing strategies successfully, and highlights what joint involvement of sales and marketing functions in MSM entails. Our findings indicate that during the various stages of the strategy making process, sales and marketing functions assume different roles and responsibilities. Successful strategy creation and execution requires both functions to be equally invested in the entire process.

We organize this paper as follows. In the next section, we review two streams of literature that provide the foundation for this study: (a) literature on marketing strategy making, and (b) sales-marketing interface literature. Next, we discuss the study methodology, followed by a presentation of the study findings. We conclude by highlighting the study contributions, managerial implications, research limitations, and future research directions.

Literature review

Marketing strategy making

Menon et al. (1999) define MSM as “a complex set of activities, processes, and routines involved in the design and execution of marketing plans.” They present a parsimonious model for MSM and highlight how successful MSM may positively affect organizational learning, market performance and strategy creativity. A review of the extant literature in both marketing and management indicates that the extant knowledge around strategy making is fragmented. We outline the many dimensions and perspectives scholars have used to study strategy making within organizations.

First, to a large extent, strategy creation has been studied independent of strategy implementation (e.g., Atauhene-Gima and Murray 2004; Gebhardt et al. 2006; Kennedy et al. 2003; Menguc and Auh 2005; Moorman and Miner 1998). Barring a few exceptions where scholars have tried to present an integrated perspective on strategy making that combines strategy creation with implementation orientation (e.g. Slater et al. 2006; Smith 2003; Tuli et al. 2007); these two streams of literatures have grown in different directions with little efforts to bridge the gap (Smith 2003).

Second, some scholars have viewed strategy making process as a set of rational choices, whereas, other scholars have taken an incremental planning perspective (Menon et al. 1999). Specifically, the rational perspective distinguishes between strategy planning and execution, suggesting that a select group of individuals within an organization (usually the top management) is responsible for creating strategic plans (Smith 2003). The incremental perspective, on the other hand, argues that in many firms, strategy creation and implementation is intertwined and that it is an emergent phenomenon (Sashittal and Jassawalla 2001).

Third, scholars have further fragmented this field by narrowing their foci to a specific aspect of strategy. For example, Shrivastava and Grant’s (1985) command and control perspective views strategy making as a prerogative of the top management. The planning and procedures-based perspective argues that strategy is derived mainly from the logical, sequential, and deliberate set of processes and activities (Ansoff 1965; Mintzberg 1978). The cultural perspective suggests that strategy creation is often guided by organizational norms and cultural frames. Other perspectives such as enforced choice (Aldrich 1979) and political orientation (Anderson 1982; Cyert and March 1963) have also contributed to this stream of literature. Some scholars have taken a narrower focus and examined strategies for properties such as its internal consistency and synergy between areas involved in strategy making process (Piercy 1997), its feasibility within organization’s resources, and whether strategy provides guidance to tactical activities (Ansoff 1965).

Sales-marketing interface

Over a decade ago, an urgent need to study sales-marketing interface was expressed by Montgomery and Webster (1997). Acknowledging its academic and managerial importance, it is only recently that scholars have started to examine this interface in greater detail (e.g. Homburg et al. 2008; Rouziès et al. 2005; Dewsnap and Jobber 2000, 2002). Barring a few notable exceptions, literature in this area is largely conceptual. In addition, scholars have investigated disparate phenomena in order to explore the interface between these functions and that has fragmented this stream of research. Scholars have highlighted major differences between sales and marketing by citing cultural differences, interfunctional conflict, and differences in thought worlds and perspectives about the marketplace (Beverland et al. 2006; Dawes and Massey 2005; Homburg and Jensen 2007; Piercy 2006). However, scholars have also identified avenues where these functions should attempt to set their differences aside and forge strong linkages. Literature suggests that these two functions should work toward aligning strategic capabilities and goals, and enhancing interfunctional cooperation, coordination and collaboration in order to jointly participate in strategic activities (Cespedes 1993; Guenzi and Troilo 2007; Ingram 2004; LeMeuneir Fitz-Hugh and Piercy 2007; Maltz 1997; Matthyssens and Johnston 2006).

While the extant sales-marketing interface research highlights the need for these two functions to work closely with one another to facilitate the strategy creation and its execution, it also acknowledges that many times, these two functions do not share a great rapport. Further, their interaction is characterized by conflict, and lack of cooperation and communication (Dewsnap and Jobber 2000, 2002). Research further suggests that the turf battles between these two functions, differences in goal orientation, lack of role clarity, misalignment of strategic objectives, and poor coordination may also reduce the probability of them working together effectively (Colletti and Chonko 1997; Hutt 1995; Lorge 1999; Strahle et al. 1996). This is reflected in the MSM processes where salespeople do not feel that the marketing strategies are useful or worth implementing (Aberdeen Group 2002; Rouziès et al. 2005).

Overall, our review of these two research streams highlights important gaps in the extant literature. MSM literature offers a fragmented perspective on strategy making by focusing either on a single dimension of strategy, or studying strategy creation and implementation independent of one another. This highlights the need for theoretical models that combine not only the rational and incremental perspectives, but also the strategy creation and implementation points of views on marketing strategy. Further, we learn from sales-marketing interface literature that these two functions ought to play a vital role in the MSM process. However, the extant body of knowledge in this area does not shed light on the specific tasks that MSM entails, how and when the marketing and sales functions should be involved in strategy making, and what roles each function should play in this process. Overall, while the extant research provides conceptual foundation for our work, it does not reveal how MSM may unfold within the sales-marketing interface or what may make strategy making more successful within this interface. We address these gaps in our study.

Research method

We adopted the Grounded Theory method for this study. Before we discuss the specifics of our methodology, we highlight three reasons why we believe a qualitative methodology such as grounded theory is appropriate to study this phenomenon.

First, as we pointed out earlier, extant literature lacks established theoretical frameworks that integrate many divergent perspectives on strategy making. Therefore, methodologies that rely on exploration and theory development, such as grounded theory, are more appropriate to study this phenomenon in contrast to approaches that rely on deductive reasoning.

Second, in grounded theory, the emergent theoretical framework is shaped by the views of the participants who are involved in the process (Strauss and Corbin 1990, 1997, 1998). Given this, we believe a better understanding of the complex issues related to MSM can be obtained by directly talking with people who are involved in MSM, and “allowing them to tell their stories unencumbered by what we expect to find or what we have read in the literature” (Creswell 2007, p 40). Further, grounded theory allows us to understand the context and the settings within which the issues related to MSM are addressed, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Last, as Gioia et al. (1994, p.367) have noted, organizational reality is essentially socially constructed; hence it is beneficial to examine such reality in a way that “taps into the processes used to fashion understanding [of that reality] by the participants themselves, and avoid the imposition of alien meanings upon their actions and understanding.” Consistent with Gioia et al. (1994) and Creswell (2007), we feel that using the grounded theory approach in our study allows us to “represent the experience and interpretations of informants (regarding MSM), without giving precedence to prior theoretical views that might not be appropriate for their context.”

We wish to note here that while we present informants’ perspectives and their subjective understanding of the phenomenon under study as recommended by the grounded theory method, our findings are a result of rigorous qualitative data analysis and not a pure acceptance of whatever our informants said at face value.

Sample and data collection

We obtained data from 69 informants using two data collection methods: (a) depth interviews with 58 sales and marketing professionals, and (b) a focus group with 11 marketing professionals.

Consistent with other marketing studies of a similar nature (e.g. Flint et al. 2002; Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Tuli et al. 2007), we used the theoretical sampling technique to select depth interview informants based their ability to provide an understanding of the phenomenon. Theoretical sampling is a non-random sampling scheme. Its purpose is to obtain a deeper understanding of the issues, and develop explanations and theory rather than provide generalizations (Corbin and Strauss 2008, ch.7). However, by selecting a diverse set of theoretically relevant informants, the researcher can see the conditions under which the emergent categories hold true (Creswell 2007, pp. 240–241).

As Table 1 indicates, our informants were sales and marketing professionals across different hierarchical levels in multiple companies from diverse industries. We wish to emphasize here that we did not deduce the level of our informants purely based on their job titles alone, since individuals with the same job title may represent different hierarchical levels within different firms. Instead, we assessed the level by triangulating two sets of parameters. First, we asked the informants to give their direct assessment of whether they considered their position to be in the middle/lower/higher level in the sales/marketing hierarchy. Second, we looked at more indirect parameters such as their job responsibility and how many layers existed above and below them in their organization.

We recruited our interview informants using personal contacts (e.g., Tuli et al. 2007). Further, we used referral and snowballing techniques to try and obtain dyadic data (i.e., interviews from both sales and marketing professionals from the same company). Specifically, we requested participation from 66 sales and marketing professionals whom we had qualified and determined were appropriate informants for the study. Eight declined the interview request for confidentiality reasons, resulting in a sample size of 58 professionals. Each informant had been in his/her current job for at least 3 years. Informant companies were comparable in size and annual sales. Each firm had distinct sales and marketing functions. There were 11 dyads in the sample. Collecting this dyadic data enabled us to get the perspective of both sales and marketing within an organization, and allowed us to check for differences between dyads and non-dyads.

The depth-interviews were conducted over 12 months. The interviews were discovery-oriented (Deshpande 1983), lasting between 40 and 90 minutes The interviews were conducted at a place and time convenient to informants. Of the 58 interviews, 50 were conducted in person and eight over the phone. The interviews began in an exploratory manner. This allowed the interviewer to focus on each informant’s phenomenological interpretations of the strategy making process as it unfolded in his/her organization (Glaser and Strauss 1967).

The focus group with 11 participants from the financial services industry was conducted toward the end of interview data collection stage. It lasted approximately 50 minutes. The purpose of this focus group was to see if it would reveal any new kind of information that did not emerge through individual interviews. Further, we chose our participants from the financial services industry to increase the variance in our sample (since our interview sample had only three informants from this industry), and also verify if the categories that emerged from the interviews would hold true in a services context. While conducting the focus group, we followed the procedures specified by Krueger and Casey (2009).

The context of discussion, both for the interviews and the focus group, was how well (or not so well) the MSM unfolded across the sales-marketing interface in the informant’s company, and what role each function played in the process. While we had a structured set of questions for the interviews in the form of an interview protocol (See Appendix A), the interviewer allowed informants to guide the flow and content of discussion. They were also encouraged to offer examples, anecdotes, clarifications, and other details as they spoke. While asking additional questions to clarify any ambiguities, we insured that there was no interviewer-induced bias (McCracken 1988). Additionally, the clarification questions provided informants an opportunity to correct anything that was misunderstood or to elaborate on certain aspects, as they deemed necessary. During the focus group, one of the co-authors played the role of a facilitator, facilitating the discussion and allowing informants to guide the discussion flow and content. Interventions were made only to clarify certain aspects of the discussion.

We audio taped all interviews as well as the focus group discussion, and transcribed the data verbatim. The 58 informant interviews represented more than 56 hours of audio recording and approximately 600 pages of single-spaced transcripts. The focus group data totaled approximately 26 pages. Toward the end of 58 interviews and the focus group, we began to encounter the same themes over and over, and no new insights were emerging from the data; a case of theoretical saturation (Strauss and Corbin 1998). At this point, we stopped the data collection process.

Data analysis

We used QSR International’s NVivo software to manage the interview notes and the focus group data. We constantly reviewed interview transcripts as the data collection progressed. This helped us identify emerging ideas and specific themes, which guided subsequent data collection efforts. To code the data, we used the open coding and axial coding schemes proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1998). In open coding, we identified important concepts using in-vivo codes (i.e. concepts based on the actual language used by the informants). We grouped these in-vivo codes into higher level concepts called first-order categories, based on some underlying similarities between them. Next, we used axial coding, wherein we searched for relationships between and among the first-order categories, and assembled them into second-order themes. These second-order themes helped us understand the emergent framework. As Corley and Gioia (2004) note, the coding techniques we used were not linear but, instead, were “recursive, process-oriented, analytic.” We continued this process until no new data relationships were found. Further, throughout the analysis, we avoided forcing emergent patterns into preconceived categories (Gummesson 2003). In Table 2, we present the in-vivo codes, first-order categories, the second-order themes, and the three-stage framework that emerged from our data. Table 3 shows representative informant quotes for specific in-vivo codes.

Reliability and validity of analysis

We took a number of steps following Lincoln and Guba (1985), and Silverman and Marvasti (2008) to maintain data trustworthiness and insure analytical rigor. First, the use of NVivo software as our data management program helped us meticulously maintain informant contact records, interview transcripts, field notes, and other related documents, as they were collected. Next, we used the proportional reduction in loss method to assess the reliability of our coding scheme (Rust and Cooil 1994). For this, we randomly selected 27 informant interviews, asked two independent judges to evaluate our coding, and calculated the proportional reduction in loss based on the judges’ agreement or disagreement with each of our codes in these interviews. The two judges had prior experience with qualitative data analysis but were not involved in the study. The proportional reduction in loss for the current study was 0.81, which is well above the 0.70 cut-off level recommended for exploratory research (Rust and Cooil 1994). Third, we asked an outside researcher experienced in qualitative methodology to conduct an audit of our empirical processes to insure the dependability of our data. This outside researcher went through our field notes, interview protocols, coding schemes, random samples of interview transcripts and documentation to assess whether the conclusions we reached were plausible. These peer-debriefing processes (Corley and Gioia 2004) provided us with an opportunity to solicit critical questions about our data collection and analysis procedures. These discussions also allowed us to have our ideas scrutinized through other researchers’ perspectives.

To insure validity, we followed five interrelated procedures recommended for qualitative research (Silverman and Marvasti 2008, pp. 257–270): (a) respondent validation, (b) refutability, (c) constant comparison, (d) comprehensive data treatment, and (e) deviant-case analysis. Respondent validation, also known as member checks (Creswell 2007, p. 208), requires that researchers go back to the respondents to validate the findings that emerge from the data. To do so, we shared the findings with 23 study participants and asked them to offer their views on our interpretations of the data and the credibility of the findings. Refutability means that researchers seek to refute the assumed relationship between phenomena. We sought to do so by having a diverse sample of both sales and marketing personnel from different companies within multiple industries, then trying to see if findings emerging in one context could be refuted in another. We observed that most of our emergent findings were consistent across the multiple industry contexts. Constant comparison implies that a qualitative researcher should try and find additional cases to validate emergent findings. This requires that the data collection and analysis begin with a relatively small data set which is subsequently expanded based on the emergent categories. Our interviews were conducted in a recursive manner to allow for constant comparison. As new findings emerged, we conducted additional interviews to validate these findings. As noted earlier, we stopped data collection when no further new findings emerged—i.e. after reaching theoretical saturation (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Comprehensive data treatment means that the researchers examine the data thoroughly and comprehensively prior to drawing conclusions. Since all our interviews and focus group discussion were transcribed and we were using the NVivo software to manage the data, we were able to inspect all our data thoroughly. Finally, deviant case analysis requires that the researchers examine all cases where the findings are substantially different, and determine the underlying reasons. In our data, we did not find any cases that could be termed as deviant.

Findings

In discussing our findings, we focus on those ideas that are insightful, were frequently mentioned by informants, are not industry specific, and have not been discussed in extant literature (e.g., Tuli, Kohli and Bharadwaj 2007).

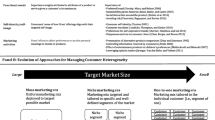

Our data revealed a process view of MSM as it unfolds across the sales-marketing interface. Specifically, it suggested that MSM within the sales-marketing interface consists of three stages: (a) Groundwork, (b) Transfer, and (c) Follow-up. Our informants felt that effective strategy making processes had to start during the strategy conceptualization phase, where sales and marketing functions together could hold formal and informal conversations about the current market conditions and the upcoming strategies, and do most of the Groundwork. Further, contrary to extant literature that discusses the notion of strategy handoff (e.g., Kotler et al. 2006), our data suggest that the Transfer stage, during which sales and marketing functions formally come together and marketing hands the strategy over to sales, constitutes just one stage in this three-stage strategy making process. Last, our data indicate that Follow-up, the third stage in this process, consists of both marketing and sales functions following-up on the activities they agreed upon during the Transfer stage, and making necessary changes to the strategies.

In addition, our data also highlighted the contrast in the characteristics of the Groundwork, Transfer, and Follow-up stages between firms where the strategy making process is sub-optimal, compared with those where the two functions are able to seamlessly create and execute marketing strategies. In Table 4, we summarize these contrasting perspectives.

In the discussion that follows, we outline each stage in the MSM process as it emerged from our data. We note here that our informant responses did not differ significantly across industries nor did the emergent strategy making process framework differ based on industry and/or company size. Further, of the 11 dyads in our sample, none of the dyad partners expressed views that would contradict their sales/marketing counterpart.

Groundwork

Our data suggest that Groundwork is the first stage of the MSM process. Three major themes emerged from our data to characterize the joint activities undertaken by marketing and sales during this first stage: giving and receiving feedback, collective sensemaking, and strategy finalization. Our data suggest that marketers insure that they get key representatives from multiple levels within the sales hierarchy involved in this process so that they get a broader representation from the sales organization. In addition, our data indicate that marketers invite key sales personnel from different territories, making sure that they hear from high and low performing sales territories during the Groundwork stage.

Feedback

Extant literature has highlighted the importance of frequent communication and exchange of ideas among various organizational functions in general (Day 1994; Kohli and Jaworski 1990), and between sales and marketing in particular (e.g., Rouziès et al. 2005; Piercy 2006), to achieve a broader organizational-level understanding of market reality. According to our informants, the MSM process begins with marketing and sales giving (and receiving) feedback to (and/or from) each other about the status quo of the existing products so that they both understand each other’s perspective about why things are (or are not) going well. It is critical that such dialog happen before marketing comes up with any new marketing plans. Our data suggest that such conversations help marketers get a clear picture of their markets so that they can incorporate these insights in strategy creation. Larry’s quote is pertinent here.

When we hear lots of critical feedback about what happens in the marketplace, about how our strategies do or do not work, competitive activities, that is fruitful. However if we just keep looking at sales numbers without discussing with the sales group why things are (not) working, then such activity does not mean a lot. We hear from salespeople before coming up with a new plan of action, we try to understand what is happening behind those sales numbers. Otherwise, we will hand over the new action plan to sales and they will fail again. [Larry, VP-Marketing: Telecom]

Not only do our informants emphasize that getting feedback from the sales group is important as the MSM process begins, but they also mention that both sales and marketing must be open about giving and receiving candid feedback at this stage. Our data indicate that marketers must insist on unearthing bad news, if any, during this stage. Ray’s quote below brings forth this point. As it highlights, if marketers do not insist on finding out the problem areas at an early stage, it is likely that the new plan/strategy will not address those areas; then the sales group will face similar hurdles during strategy implementation.

If something is not going well, marketing should be hearing about that. If salespeople are trying to fix things on their own, they might not share it with marketing. For me, as soon as I hear something that is negative, I ask to hear more. I am interested in the specifics…what is the issue with the product, or customer service? You have to dig a little bit deeper to get the full picture because unless you know all the problems, you will not be able to address them in your new plan and the new plan will also fail because salespeople will encounter the same problems…it has to start here. [Ray, VP-Marketing: IT]

Collective sensemaking emerged as a second theme that characterizes the Groundwork stage. The concept of sensemaking has been studied in extant literature on strategy and organizational learning (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Daft and Weick 1984). Specifically, it refers to the organizational members interpreting the incoming market information in the context of extant organizational knowledge to figure out what is going on in the external environment (Bogner and Barr 2000; Weick et al. 2005). Consistently, our data point out that when both marketing and sales functions collectively interpret market information, and try to make sense of their successes and failures, it provides a strong foundation for the strategies being created. Many of our informants noted that if the two departments did not come together to make sense of what the market data meant, they might not be able to exploit the available information in the best possible manner. This is consistent with the literature on organizational learning, which exhorts that multiple departments within the organization must collectively interpret what market information means in order for the firm to have a superior market insight (Kim 1998; Nonaka 1991, Zahra and George 2002). Our informants further mentioned that such collective sensemaking could set the right tone for strategy transfer (later) because sales organization would be aware of the current market information and its analysis, based on which marketing would create its new plans.

Marketers mentioned that when sales group were involved in the sensemaking process at an early stage, it was easy to get them onboard with marketing strategies later. Rochelle notes:

What we do is we take the sales group along and do an overview of what happened in the previous year from the sales side and marketing side. I will do my part of it and my counterpart in sales will do his part. We let everybody see the performance of last year, the markets we were successful in, the customers we are successful with, some of the campaigns that we did and how they turned out…and then, we argue what went wrong where…what are the learnings…the key here is to have sales organization in this process. Later on, when you come up with a new plan, you do not face many questions such as why this and why not that (laughs). [Rochelle, Marketing Manager: Pharmaceuticals]

Nathan expressed a similar opinion. As his quote below indicates, his marketing colleagues actively involve salespeople in ongoing discussions and they collectively understand what is going on in the marketplace. In fact, the sales function’s opinions and interpretive insights form the foundation for their marketing attack plan, which the salespeople then execute.

We sit down with sales team and together, we decide what we are trying to achieve with this account. We go through their major customers’ organization chart, and the political aspects of it such as who are the influencers versus decision makers…and then we put together a marketing communications attack plan…we also do research on some key industries and find out what are the pain points for customers in those industries. I like to do this before we do a marketing attack plan. [Nathan, VP-Sales: IT]

Randy, another informant from an engineering firm highlighted how it is important to include the sales group in making sense of the market information.

I consider not inviting salespeople to the table and not giving them an opportunity to comment on market information as a wasted opportunity. They have unique insights and marketers must do everything to capture that insight. They often assess the market information from customers’ perspective, which is very valuable…it is worthwhile spending time with salespeople during early stages and making sense of what the market data mean [Randy, Sales Manager: Engineering]

Finalization is the last theme to emerge from our data to characterize the Groundwork stage and represents a collaborative effort between sales and marketing in strategy finalization (Kahn 1996; Ruekert and Walker 1987). It is helpful if marketers review their final strategic plans with select members of the sales group. Jill and Sandra’s quotes below are pertinent:

I think it is critical that they include some of our senior reps while finalizing new strategies and new products for a variety of reasons. First, you want to keep your salespeople happy. Therefore, if you give them a sense that they are involved in the process, then they can own up the strategy later…and the other part is, many times, they have good ideas. So, by listening to new strategies, they can instantly tell you whether it is going to fly. [Jill, District Manager: Industrial products]

When we finalize our plans, we insure that we run it by key sales constituents and get their feedback. It is never late to get salespeople’s feedback. They always have something interesting to say and as marketers, we must exploit their knowledge. [Sandra, Senior Marketing Executive: IT]

When marketing reviews plans with the sales organization, salespeople have an opportunity to comment on whether marketers’ ideas are sound (Piercy 2006). In addition, when included in this step, the sales organization is also able to assess the feasibility of specific activities they would need to perform to implement the plan. As Tricia notes, if marketers use this feedback to modify their plans before introducing it to the sales group, they are less likely to face resistance at a later stage, which extant sales-marketing interface literature highlights as a major concern (Rouziès et al. 2005).

First is looking at what we are trying to launch. We do several layers of process mapping to make sure that if the plan were implemented, it is a process our sales force can easily use. Then we try to get direct feedback from sales such as….does this make sense? Is this something you can relate to? Does this resonate with you? How, based on a 40–50-hour workweek, can you make time to make something like this work? And if you are going to make time to make this work, what aren’t you going to do to free up your time, and what will that cost us. [Tricia, Marketing Manager: Pharmaceuticals]

Our data also suggest that marketers should send out “feelers” to the sales organization about upcoming strategies. Our sales informants noted that they like to get a sense of upcoming strategies so that they could start preparing for them. For example, if future plans entail targeting a new group of customers, its advance knowledge would help salespeople start preparing a list of potential customers that they could target once the new strategy is launched.

Transfer

Transfer emerged as the second stage in the three-stage strategy making process. Our data suggest that once the preparatory work, as outlined in the Groundwork stage is completed, marketers feel ready to discuss the strategies with the entire sales organization. This is the stage where marketers formally present their plans to the sales force during sales meetings or such events. Consistent with the extant literature, such meetings are held periodically at 3-month or 6-month interval in many firms (Donath 1999; Kotler et al. 2006). There are three major themes that characterize the Transfer stage: (a) strategy delineation, (b) creating action plans, and (c) good closure.

Strategy delineation

It entails marketers unveiling the details of their strategies to the entire sales group. Our informants mentioned that marketers needed to follow some cardinal rules during strategy delineation. First, it was necessary that marketers simplified the strategy for the sales group and discussed it using “their language.” When marketers left their “marketing jargon” behind and used “common terminology” to discuss the core strategy with the salespeople, it was very effective. This is consistent with Oliva (2006) who highlights the need to forge stronger linkages in “language” between sales and marketing so that they both are on the same page. Aaron notes:

Salespeople do not really care about whether this strategy will enhance our brand equity…to them, the term brand equity does not mean a squat in the broad scheme of things. However, if I discuss the same idea using language they understand, they are more receptive…so I tell them how this strategy will help get more repeat business or how it will help us change customer perceptions…if you think about it, I am talking brand equity…but in terms that make sense to them. [Aaron, Product Manager: Healthcare]

The second rule was that marketers should not throw any surprises during strategy delineation. The surprises could come in the form of changing the strategic approach radically as compared to what was agreed upon during the Groundwork stage, or setting ambitious sales targets that the sales group would not feel achievable and hence would not agree to. Our data suggested that such surprises were detrimental because they undid all the work that members of both sales and marketing teams had put in during the Groundwork stage. When marketers threw in such surprises, sales organizations felt compelled to deviate from the strategy and recalibrate their goals and objectives. Our informants noted that if marketers engaged in such behaviors, over time, it led to interdepartmental conflict (Dawes and Massey 2005; Dewsnap and Jobber 2002; Montgomery and Webster 1997) and resulted in strategy implementation failures.

We avoid surprises. Nothing upsets the sales organization more than when they feel that something is coming out of the blue…that we agreed upon certain things and then we are telling them to do something else….it just builds up their resistance …and if that happens, you lose them instantaneously. [Tricia, Marketing Manager: Pharmaceuticals]

Third, it was important during the strategy delineation that marketers listened to questions and criticism from the sales group (Carpenter 1992; Rouziès et al. 2005). Our informants mentioned that inviting criticism helped marketers enrich the discussion about the marketing strategies that were on the table. Last, it served marketers well if they co-presented the new strategy with some of the salespeople who were a part of the feedback, sensemaking, and strategy finalization activities during the Groundwork stage. Our informants referred to these individuals as “strategy champions” or “star salespeople.” Since they belonged to the sales force, their comments and enthusiasm about the new strategy enhanced its credibility in the recipients’ eyes. It also allowed the sales force to see that their representatives were involved in strategy creation, which blurred the lines of demarcation between sales and marketing (Donath 1999; Lorge 1999).This facilitated the process of Transfer.

We discuss with the sales group the broad strategic approach and then turn it over to our star salespeople to do the job. Our strategies come across as very authentic when these strategy champions talk about it…I bet if I were to lay it out, I would face tons of questions…and the process would not be nearly as smooth. [VK, VP-Marketing: Financial services]

Action Plans

The second theme that characterized this stage was creating action plans. As many of our sales informants reported, it was important that salespeople were able to take the strategy presented by marketers and translate it into specific action plans that they would execute, once they were out in the field. As Marcus pointed out:

The difference between strategy and tactics is that one is the philosophy and the other is the reality. The philosophy needs to be translated into reality before we can move forward. [Marcus, Regional Sales Manager: Telecom]

Our data suggest that it was helpful when the sales organization was allowed a significant amount of time to come up with action plans that could translate the strategy into tactics during the Transfer stage. It also helped if they got direction from their marketing colleagues as they engaged in this activity. A related facet of this theme was “bringing strategy from ten thousand feel-level to the ground level.” Existing research suggests that salespeople differ from marketers on many fronts such as thought worlds, roles and responsibilities, and cultural orientation (Beverland et al. 2006; Homburg and Jensen 2007). Many of our informants from the sales organization noted that for the strategy making exercise to result in successful strategies, marketers had to make conscious efforts to bring both functions on the same wavelength (Donath 1999). This was consistent with the philosophy-reality distinction and the need to translate ideas into specific action plans mentioned above.

At the end of the day, we have to let everybody digest the strategy…so we get all the notes together and everybody has a chance to look at them. Then we have a session where we look at how to make sense of this plan. So, we start taking what used to be the 10,000 foot view and take a closer look at it…saying does this make sense for the business. Usually, we identify about five strategic goals, put them on the whiteboard, and talk about specifics…for example, what do we need to do to achieve these five goals, what will salespeople do, what will field managers do…the devil is in the details and this process is crucial. [Donald, VP-Sales: Telecom]

Extant strategy research suggests that strategy making process involves a great deal of teamwork involving people within multiple functions, with each participating function contributing its own resources and capabilities throughout the broader process (Ruekert and Walker 1987; Narver and Slater 1990). Our informants expressed similar opinions. Specifically, salespeople believed that marketers’ counsel should be available to them when they needed it during this process. As our data suggested, when the actual action plans were being crafted, it helped if marketers entertained salespeople’s questions and ironed out tactical glitches instantly.

I should be able to sit there and have that discussion with my marketing managers about what we need to do and how we could implement the new plans. We want marketing managers to discuss with us how we are going to attack our customer base with this product strategy… what activities are going to work and what is not going to work with this product. We should be able to get clarifications to our questions right there because once we leave that meeting, we are on our own. [Miles, Sales Representative: Industrial products]

Closure

The third theme that characterized the Transfer stage was having good closure. As our informants noted, good closure served two purposes. First, it was an appropriate culmination of the Transfer stage. Second, it served as a good starting point for salespeople’s activities once they took the new strategies to the field. Our data indicated that throughout the Transfer stage, salespeople received lots of information from their marketing counterparts about the market, their customers and products, as well as competitive activities. Hence, before they left for the field, it was important that they synthesized their key priorities and had a plan of action. Our data indicated that a strong closure helped refocus salespeople’s attention on key aspects of the strategy. Strategy literature has highlighted how leaders, through their involvement, can set a proper tone for various organizational activities (Kirca, Jayachandran and Bearden 2005; Kennedy et al. 2003). Consistently, our data indicated that it was a job of both marketing and sales leadership to insure that both sales and marketing personnel have an appropriate closure at the end of the Transfer stage and that they understand their priorities clearly.

At the end, it is important to refocus salespeople on things that are critical. The timing is important because immediately after the meeting, they get back to the field and start implementing the plan. If they can remember one or two key things that they need to do in the field, if they are able to set their priorities, if they understand what the big opportunities are, and if they are able to create a mental plan to capitalize on those opportunities, that, to me, would be a very good culmination. [Saad, Director of SBU Sales: Healthcare]

Good closure also made salespeople excited about their new plans as Mel indicates.

I think that interaction that takes place…the overall tone of the meeting affects salespeople once they go out in the field. If I do not feel great about my job after interacting with marketing, if I walk away thinking that we, as a company, are not doing the right things, then I am not fired up. On the contrary, I am nervous…and that is the last thing I want…is to be nervous in front of my customers. [Mel, Sales Support Specialist: Engineering products]

Follow-up

Our data indicated that successful strategy making processes did not have a point of demarcation (e.g., the Transfer stage), where marketing would believe that once they discussed the strategy with the sales group, their responsibility was over and that it was up to the sales function to execute the strategies. Effective strategy making included a systematic post-transfer follow-up stage where marketing was equally involved in the execution phase. Our data suggested that interfunctional coordination and connectedness (Narver and Slater 1990) played an important role in insuring that firms handle the Follow-up stage appropriately. Specifically, it indicated that during Follow-up, it was imperative that both departments coordinate their activities, so they could implement the action plans created during the Transfer stage (Colletti and Chonko 1997). Further, implementation of action plans required marketers to offer their resources to the sales organization and be supportive of their activities even after the Transfer stage was over (Rouziès et al. 2005). Three themes emerged from our data that characterized this stage: (a) check-in, (b) bidirectional communication, and (c) strategy fine-tuning.

Check-in

During the Transfer stage, salespeople work out details of specific activities they would undertake to implement strategies. Our informants mentioned that even after action plans were outlined and all details were discussed, once the strategies were executed in the field, it was important that both functions periodically checked-in with each other and made sure that the execution was on the right track. This finding concurs with some marketing strategy literature that argues for frequent interaction among the various strategic and tactical functions to insure that implementation happens seamlessly (Sashittal and Jassawalla 2001). The following two quotes highlight this aspect clearly.

It is important to keep checking in with your sales counterparts about how things are going. You can not simply say, my work is over…now I will sit back and see what happens…you have to be involved…you need to make sure things are on track. [Margaret, Product Manager: Industrial products]

As a salesperson, I feel it is crucial for me to constantly keep checking with my marketing colleagues. It has always helped me to run my ideas by someone in marketing…many times, I have updated my marketing colleagues about the specific problems I am encountering with some customers and sought their opinion about how to handle that situation. [Colleen, Sales Representative: Telecom]

Bidirectional communication (Mohr and Nevin 1990; Mohr and Sohi 1995) emerged as another important facet of the Follow-up stage. Once salespeople went off to the field, such communication allowed marketers to respond to questions and concerns that the sales organization had raised during the Transfer stage. It also allowed marketers to get a first-hand feedback from the salespeople about how their new strategies were received in the marketplace.

Salespeople get all this great front-line feedback, which we could benefit from if we had access to it. It really helps to have good communication lines once people go out in the field…it allows salespeople to share their successes and failures…and in marketing, we can make it clear what types of intelligence, what types of information is of greatest value. We have been trying to work on it for a while now. [Christine, Product Manager: Healthcare]

Strategy fine-tuning

The last theme that characterized the Follow-up stage was strategy fine-tuning. It is intuitive that in business markets where sales-cycles are long, salespeople are likely to face unexpected obstacles while implementing marketing strategies. Our informants mentioned that once salespeople were out in the field, it was necessary that they received marketers’ support in surmounting unanticipated execution challenges (Yandle and Blythe 2000). In addition, implementation success depended on whether the two functions, together, were able to make modifications to the action plans if their original strategies did not succeed as expected. In such instances, marketers’ flexibility and willingness to accommodate deviations from the agreed upon plans was crucial (Carpenter 1992).

The reason why we have been so successful for the past 5 years is that we are open to making changes to our action plans if need be. Last year, two territories on the west coast were struggling. They were doing everything according to our plan…but something was missing there. What we realized that our message was not resonating with three major customers and our salespeople were having a hard time. We assessed the situation and decided to change our message. If we were to not be flexible, and insist they [salespeople] stick to the strategy that would have been foolish. You must make sure that your strategies are working on the field. [Catherine, Marketing Specialist: Financial Services]

I always tell my salespeople that I am open to revisiting parts of our strategy if they felt that it did not work in the field...sometimes, the business environment changes so dramatically that you have to make course-correction. I think that is a great ability and every organization should develop that. [Rory, Senior Marketing Executive: Telecom]

Contrasting effective vs. sub-par strategy making processes

In the preceding section, we highlighted the characteristics of successful MSM process within the sales-marketing interface and presented a nuanced picture regarding the various stages and the facets involved therein. However, our analysis also showed that in some firms, the MSM process was not as successful compared to other firms in our sample.

To categorize firms as effective or sub-par strategy makers, we used three sets of criteria. First, based on our questions related to marketing strategy creation, we assessed the extent to which a company had problems and challenges in terms of sales and marketing working with each other through the various stages of MSM. Related to this, we also examined how they handled these problems and if there were any lacunas in the strategy making process. Second, based on our questions related to strategy implementation, we determined the extent to which the company had effective execution processes. Third, we assessed if the MSM process led to effective/sub-par strategies, by asking the informants whether the particular strategy succeeded or not.

We wish to note here that although we categorized companies as “effective” or “sub-par” strategy makers on a post-hoc basis, we assessed the validity of our categorization during the member checking phase mentioned earlier. For the member checks, we specifically selected informants that represented both the effective and sub-par strategy making firms, and asked them to reflect upon our characterization of their firm’s strategy making process. Our informants were in agreement with our interpretations, which served as a validity check.

We found examples of both sub-par and effective strategy making across diverse industries, and there was no evidence to suggest that the effectiveness of MSM depended on firm size or other firm/industry-related variables. Our analysis showed that the three stages—Groundwork, Transfer, and Follow-up, were notably different for companies with effective strategy making process from those with sub-par processes. Next, we highlight the differences for each stage. Table 4 shows specific examples of these differences.

Groundwork

As noted earlier, collective sensemaking serves as an important activity during the Groundwork stage since it helps companies analyze market data through different perspectives. Since the sales and marketing groups may look at the same issues through different lenses, it is likely to enrich the quality of insights they may get out of such analysis. Our data suggested that even after gathering feedback from salespeople about the existing market conditions, if marketers did not engage them in discussing what the information meant, the strategy making process was affected. As the quote below from Pamela suggests, absence of collective interpretation process is a weakness in her firm’s strategy making process since it does not allow a nuanced picture of the situation to emerge.

Marketing organization gets most of their research from the vendors, internet, anecdotal, bits and pieces from people internally within the organization. Information that is collected by salespeople is from real customers who are using either our products or somebody else’s. We do not have any mechanism to integrate the information that comes from the sales force and marketing and look at it collectively…if we were to do that, it would allow both the strategic and tactical perspectives to come together and present a much-nuanced picture. [Pamela, VP-Sales: Engineering products]

As noted earlier, our data suggest that salespeople liked to get a sense of upcoming strategies so that they could start preparing for them. In firms where the strategy making processes were sub-par, we observed that marketers seldom sent out “feelers” to the sales organization about the upcoming strategies. Mary complained that this never happened in her company.

They never send out any early communication to the field about what to expect [with new strategies]. It is always a guessing game for us. The reps need to get a sense of what they are going to be doing in future so that they can start planning. No one in marketing understands this. We have told them so many times that we are very happy to discuss the strategy with you…and in order for us to be effective; you guys have to bring us onboard…we are still waiting for the invitation. [Mary, Sales Manager: Healthcare]

Transfer

Certain characteristics of the Transfer stage also differed across the two groups. We observed that for firms in the sub-par group, marketers often violated the “cardinal rules” we discussed earlier. First, the plans and ideas marketers presented to the sales group were not consistent with the earlier conversations they had with sales group. In such situations, marketers did not even explain why the strategy was changed. Katie expressed surprise over such behavior.

What surprises me in this company is that many of my marketing colleagues make last-minute changes to their plans and present it to sales…if I were a salesperson; I would be agitated…you promised one thing and you are saying something else. [Katie, Marketing Manager: Pharmaceuticals]

In addition, when marketers presented their ideas, they were less open to entertaining questions from the sales organization. The interfunctional communication was not consultative and bidirectional (Carpenter 1992; Lorge 1999). Rather, it was unidirectional in that marketers were instructing salespeople to perform certain tasks.

All that we [salespeople] do is hear them talk. They present their plans and then it is up to us what we want to do with it. What is most frustrating is they are not willing to listen to our objections. First, they do not ask our opinions before creating their grandiose plans…and then when they present it, they do not even entertain our questions…it is a joke. [Valerie, National Account Manager: Telecom]

We also observed that in companies where the strategy making process was sub-par, salespeople weren’t given an adequate amount of time to come up with action plans that could translate the strategy into tactics. This had a huge effect on strategy implementation later as Libby indicates below.

The product we launched last fall is a great example. We had great intentions, and we believed that the product was good. However, somewhere along the way, the intentions did not translate appropriately into plans and programs. Therefore, there was a big problem when it came to implementing the strategy because the tactical part had little correlation with the strategic part. The biggest problem we identified later was that we did not spend enough time when we met to discuss the specifics of sales tactics. [Libby, Marketing Support Manager: Industrial products]

The last difference in the Transfer stage between these two groups of companies was that companies with sub-par strategy making processes did not pay adequate attention to Closure. In such companies, marketing did not make the key priorities clear to the sales group. The salespeople did not have a proper sense of direction, and marketing did not spend enough time answering their questions and addressing their concerns. Further, salespeople in such companies weren’t too excited when new strategies and programs were presented to them.

In the past 5 years, I do not remember coming out of any meeting and being all charged up…it has never happened, period! And it is not I alone, many of my [sales] colleagues feel the same way…if I do not feel excited about new strategies, no matter how much I try, I am not going to be effective. [Kendra, Sales Representative: Engineering products]

Follow-up

The major difference during the Follow-up stage was that in companies with sub-par MSM processes, once the sales team took strategies to the field, there was no check or control from marketing’s side with respect to whether the strategies were being implemented in the manner they were supposed to be. What came across was that in such companies, marketing “retracted” once they handed the strategies to the sales organization. This lack of follow-up by marketers dampened the momentum that was created during the Transfer stage, thereby affecting implementation.

Sometimes, strategies-once they are rolled out in the field do not sail smoothly…I have seen my salespeople struggle with some customers, or sometimes the message not resonating with customers…and in cases like this, I would like marketing to be there to support my people and answer their questions and insure that things are on track…what is disturbing, and to tell you the truth it is very irritating, about our marketing colleagues is that they simply throw the strategies over the wall and then sit back and just watch it from a distance…it is like it is in your hands now and you deal with it…there is no follow-up about how things are and if salespeople have any issues in the field [Andy, District Manager: Pharmaceuticals]

Discussion

Existing scholarly research in marketing strategy and sales-marketing interface stresses that the sales function be involved in marketing strategy making and that the sales and marketing organizations must synchronize their strategic and tactical activities in order to make strategies that create, deliver, and communicate superior customer value (Cespedes 1996; Guenzi and Troilo 2007). A close examination of the stream of literature on MSM, however, reveals that there is a lack of theoretical frameworks that (a) combine the planning and implementation orientations, (b) highlight the process perspective of MSM, and (c) help us understand how marketing strategies may best be made when different, yet closely-related functions such as sales and marketing are likely to be involved in the process. Extant management literature has highlighted the various types of organizational strategies and broad steps involved in strategy formulation (Chaffee 1985; Feurer and Chaharbaghi 1995; Harrigan 1980; Huff and Reger 1987; Narayanan and Fahey 1982). However, it hasn’t explored the nuances and finer details of the strategy creation process. Further, management literature has pointed out that researchers need to “conduct more studies that explore the effects of the individuals involved in the strategy processes” (Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst 2006). Against this backdrop, the aim of this study was to obtain a detailed understanding of what a joint involvement of sales and marketing functions in the MSM process may entail.

Our findings indicate that successful MSM across the sales-marketing interface entails three main stages—Groundwork, Transfer, and Follow-up. Our data suggest that the strategy making process begins at the Groundwork stage with both marketing and sales functions beginning a conversation about the status quo of their firms’ products and services. It is important at this stage that these functions maintain an open, bidirectional conversation and provide feedback to one another, so that each party gets a clear picture of the environment they are operating in. It helps firms when such open exchange of ideas is followed by collective interpretation—i.e. sales and marketing executives at various levels collectively interpreting the information and sharing those interpretations with each other. This allows many different perspectives about a given situation to emerge, thereby enriching the firms’ understanding of the market reality. Firms that have successful strategy making processes also work toward finalizing their marketing strategies at this stage, before rolling them out to the entire sales force. Marketing executives in such organizations use insights from their dialog with sales colleagues to fine-tune their marketing strategies. Many times, they test-market their strategies in certain territories and tweak them, if necessary.

Once the groundwork is completed, strategies are transferred to the sales force. During this stage, a successful strategy making exercise entails marketers explaining the strategy to the sales organization and explicating its underlying rationale and nuances in greater detail. Our data show that the strategy transfer is facilitated if marketers involve “strategy champions” during the process. It is also important at this stage for marketers to be open to sales force’s questions and concerns regarding the strategies. For Transfer stage to be effective, marketers must also allow their sales counterparts to come up with tactical action plans so the strategies can be implemented in the field. This is an important task since it allows the sales force to translate the strategic “philosophy” into ground “reality” and understand the activities involved in implementing marketing strategies. This is a lengthy process and it is crucial that this task is achieved successfully during the Transfer stage. It is also important that the Transfer stage culminate with appropriate Closure wherein both marketing and sales leadership refocus sales force’s attention on key issues, priorities, and a specific set of activities/action items to implement in the field. Our data suggest that a good Closure also helps in getting salespeople excited about their work ahead.

Marketers’ responsibility does not end once they roll out their strategies. Our analysis indicates that the third stage—Follow-up, requires marketers to be equally involved in the process, albeit on the back end. At this stage, although the sales force “takes over” the strategies, both functions are required to “check in” with one another so as to maintain consistency between the plan and its implementation. It also allows parties involved, to follow-up with each other on the status of the various assignments discussed during the Transfer stage. Bidirectional communication, once again, proves crucial at this stage since it allows information to flow freely, and spots troubles in the marketplace quickly. Using the market information, marketing and sales functions fine-tune their strategies many times during this stage (Fig. 1).

We must reemphasize here what our earlier discussion has already pointed out. The three-stage strategy making process, as it unfolds within this interface, is dynamic. Further, during the entire process, a constant exchange of ideas and information takes place between sales and marketing functions. In addition, these two functions go back and forth during each stage in order to optimize the outcomes.

Our data also revealed some important differences between firms where the strategy making processes and the resultant strategies were effective, versus those where they were sub-par. We observed that the characteristics of each of the stages are somewhat different in the two situations, and if firms stray away from some of the important activities outlined for each of the stages, it hampers the strategy making process and the resultant strategy.

We must note here that of the 58 informants we interviewed, there were 11 dyads in our sample—i.e. sales and marketing professionals belonged to the same companies. When we compared their insights of this phenomenon with those from the remaining informants, no major differences in their perspectives emerged. In addition, we heard many of the same concerns being echoed by both the sales and marketing professionals within each dyad. There were no instances where a sales (or marketing) professional had a contrasting perspective on a particular issue, when compared to his/her dyadic counterpart.

Theoretical contributions

Extant strategy research in marketing and management has examined elements such as strategic orientation, strategy making, and strategy execution at three levels: corporate, SBU, and functional-level (Varadarajan and Yadav 2002). Irrespective of the focus of examination, as noted earlier, theoretical frameworks that combine the strategy planning and implementation orientations, and highlight the process perspective of MSM are absent in extant literature. While Slater and Olson (2001) view strategy as the firm’s broad plan of action to achieve and maintain competitive advantage, it is also suggested that during strategy making and execution, firms must constantly strive to adapt to external environments (Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001; Peteraf and Barney 2003; Varadarajan and Jayachandran 1999). Management scholars argue that this may be achieved by constantly focusing on activities such as planning, organizing, coordinating, creating appropriate organizational structures or developing key resources and capabilities (Barney 1991; Huff and Reger 1987; Sirmon et al. 2007). Marketing scholars, on the other hand, urge firms to deploy their resources in understanding market segmentation, targeting and positioning aspects of strategy as well as building customer relationships, channel management, and new product development capabilities (Hunt and Morgan 1995; Menon et al. 1999; Vorhies and Morgan 2005; Srivastava et al. 2001) so as to keep up with the changing business environment. Overall, the above discussion indicates that extant marketing and management literature has focused on broader, macro-level strategic issues such as adapting to external environment, organization-wide planning, or creating and deploying resources and capabilities to target specific markets, ignoring the micro-level nuances of strategy making at a functional level.

Against this backdrop, the first contribution of our study is that it integrates diverse streams of literatures on strategy making with research on the sales-marketing interface to provide a unified thesis regarding the nature and dynamics of MSM at a micro-level, i.e. within the sales-marketing interface context. Specifically, the process model we propose helps to combine both the strategy creation and execution perspectives as well as the rational and incremental schools of thought that have been explored independently in strategy making literature in marketing and management into one model. Further, offering the MSM model that is consistent with Menon et al.’s (1999) definition allows us to not only highlight the potential building blocks of the firm’s broader plan of action (Slater and Olson 2001) at functional level, but also exhibit how firms may plan, organize, and coordinate various activities (Huff and Reger 1987) at the functional level, to create successful marketing strategies.

Next, in spite of scholars’ repeated exhortations to involve various organizational functions in strategy making in general (Kirca et al. 2005; Krohmer et al. 2002; Menon et al. 1999) and sales function in particular (Cespedes 1993; LeMeuneir-FitzHugh and Piercy 2007), extant literature is silent about how and when the marketing and sales functions should be involved in MSM and the specific roles they may play in this process. The second contribution of this study is that it fills this gap in the existing literature by offering a three-stage, process-based model that explicates how MSM process may unfold within the sales-marketing interface. Specifically, identification of three stages in this process—Groundwork, Transfer, and Follow-up; along with the explication of the various themes that characterize each of the stages helps us appreciate many of the hitherto unexplored facets of MSM. In doing so, this paper also responds to the call by scholars to study the specific set of activities and processes needed to develop and execute strategies (Hutt, Reingen, and Ronchetto 1988; Menon et al. 1996; Mintzberg 1994; Ruekert and Walker 1987) and explore in greater detail the effects of the individuals involved in the strategy processes (Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst 2006).

The third contribution of our study lies in highlighting how the various concepts already studied in strategy literature are fundamental to understanding the MSM process within the sales-marketing interface. A case in point is the notions such as interfunctional communication (Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Ruekert and Walker 1987), coordination (Narver and Slater 1990), or collaboration (LeMeuneir-FitzHugh and Piercy 2007; Rouziès et al. 2005), which as our study shows, play a crucial role in MSM. In addition, the proposed process perspective of MSM extends our knowledge of sales-marketing interface by highlighting the importance of specific activities that characterize successful MSM process within this interface—e.g., collective sensemaking, strategy delineation, creating action plans, achieving good closure, or checking-in with each other. Similar notions have been cursorily been alluded to in the trade literature (e.g. Carpenter 1992; Donath 1999). However, no scholarly research has empirically elucidated what these concepts entail and how they contribute to a strategic process within the sales-marketing interface.

The fourth contribution of this study is that it highlights the contrast between effective and sub-par MSM processes within the sales-marketing interface. Our findings suggest that in firms where strategy making process is sub-par, Groundwork is not exhaustive and marketing does not involve the sales organization in sensemaking and strategy creation processes. Further, in such firms, marketing is not open and receptive to salespeople’s ideas or objections during the Transfer stage. It does not work with the sales function to translate ideas into tactics. Last, there are lapses when it comes to Following-up on the agreed upon action plans and salespeople are left on their own with no support from marketing during the implementation stage. Owing to the lack of process-based models in the extant literature, this comparison helps us gain deeper insights into the theoretical underpinnings of MSM.

The fifth contribution of this study lies in highlighting the fact that successful strategy making constitutes a continuum of activities across the three stages. This suggests that there are no definite lines of demarcation of responsibilities, when one function may “hand over” the strategy responsibility to the other function (Kotler et al. 2006). Further, it highlights that a distinct division of labor between sales and marketing may not lead to optimal strategy making process, and that each function needs to support the other in every step of the way.

Last, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study using qualitative data that explores the nuances of MSM across the sales-marketing interface. In doing so, our study addresses a dire need for empirical work that examines important strategic phenomena within the sales-marketing interface (e.g., Rouzies et al. 2005). In addition, studies using qualitative data in sales context are scarce. Hence, the use of qualitative methodology also constitutes a contribution to the sales literature as such.

Managerial implications

Our findings may help managers identify important lessons with respect to involving sales organization in the process of MSM. The first and the biggest take away for marketing managers is that MSM activity is a multifaceted process that consists of three distinct stages. This suggests that marketing managers must involve (and stay involved with) the sales organization during all three stages of this process if the resultant strategy and its implementation were to be successful. The explication of each of the stages will help managers understand specific activities they need to undertake to come up with the best marketing strategy.

Managers will understand that solid groundwork based on extensive feedback from the field, and collective sensemaking of market information, lays the foundation for successful MSM. Accordingly, during the strategy conceptualization phase, marketers must create avenues for the field force to share their perspectives on the status quo of the products. They will also appreciate the importance of involving the sales force in the data analysis process. Organizations may create joint sales-marketing task forces so that they can share information and collectively analyze market feedback. Marketers must also involve sales force in strategy finalization. Specific activities may include test-marketing some ideas in the field to assess their feasibility or reviewing strategies with some key players (e.g., sales leadership, influencers such as star salespeople/managers) before a large-scale rollout.

During the Transfer stage, marketers must clearly delineate strategies to the field force and remain open to questions and criticism from the field. It helps if they invite members of the sales force to play a devil’s advocate and poke holes in their strategies. Further, marketers may use some members of the sales organization in presenting new strategies. Our findings further suggest that while transferring strategies to the field, marketers must communicate the strategy using the language that salespeople feel comfortable with. This is the stage where marketers must help translate the strategic philosophy into reality; i.e. what it entails and how to execute it. Relatedly, marketers must insure that sales organization prepares specific action plans that are consistent with the core ideas of the marketing strategies. Last, marketers must achieve a good Closure so that the field force is excited about their strategies and feels equipped to implement those in the field.

Marketers’ involvement in the strategy making process is not over once they detail strategies to the sales force and once they prepare action plans. This is the fourth insight from this study that marketers may find useful. Our findings suggest that both functions must check-in with one another periodically after strategy is transferred to sales force. Organizations may create platforms such as weekly conference calls for such check-ins to take place. As our findings indicate, check-in allows marketers to be involved and insure that the strategies are being implemented in an appropriate manner. At this stage, it will help if both functions maintain bidirectional communication. It is also important that marketers remain flexible to tweaking marketing strategies, if need be, after they have been Transferred to the sales group.

Limitations and future research directions