Abstract

Many ethnic minorities in Europe have a higher type 2 diabetes (T2D) prevalence than their host European populations. The risk size differs between ethnic groups, but the extent of the differences in the various ethnic minority groups has not yet been systematically quantified. We conducted a meta-analysis of published data on T2D in various ethnic minority populations resident in Europe compared to their host European populations. We systematically searched MEDLINE (using PUBMED) and EMBASE for papers on T2D prevalence in ethnic minorities in Europe published between 1994 and 2014. The ethnic minority groups were classified into five population groups by geographical origin: South Asian (SA), Sub-Saharan African (SSA), Middle Eastern and North African (MENA), South and Central American (SCA), and Western Pacific (WP). Pooled odds ratios with corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) were calculated using Review Manager 5.3. Twenty articles were included in the analysis. Compared with the host populations, SA origin populations had the highest odds for T2D (3.7, 95 % CI 2.7–5.1), followed by MENA (2.7, 95 % CI 1.8–3.9), SSA (2.6, 95 % CI 2.0–3.5), WP (2.3, 95 % CI 1.2–4.1), and lastly SCA (1.3, 95 % CI 1.1–1.6). Odds ratios were in all ethnic minority populations higher for women than for men except for SCA. Among SA subgroups, compared with Europeans, Bangladeshi had the highest odds ratio of 6.2 (95 % CI 3.9–9.8), followed by Pakistani (5.4, 95 % CI 3.2–9.3) and Indians (4.1, 95 % CI 3.0–5.7). The risk of T2D among ethnic minority groups living in Europe compared to Europeans varies by geographical origin of the group: three to five times higher among SA, two to four times higher among MENA, and two to three times higher among SSA origin. Future research and policy initiatives on T2D among ethnic minority groups should take the interethnic differences into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The global burden of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is high and is increasing rapidly [1]. During the past two decades, the T2D burden has attained far greater proportions in the US and Europe than before [2, 3]. In Europe, T2D is one of the biggest public health challenges. About 6.8 % of the adult population in Europe has T2D, and it accounts for one in ten deaths [4]. Evidence suggests that ethnic minority populations are more affected compared with the European host populations [5]. For example, the prevalence of T2D is 1.3–2.8 times higher in Turkish and 1.9–3.2 times higher in Moroccans than in Europeans [6]. The T2D prevalence rates are not only increased compared to their host populations, they also differ greatly between the ethnic groups [6–8].

In line with the current increase in T2D, there is a worldwide growing epidemic of overweight and obesity. Overweight and obesity as a result of an unhealthy lifestyle are identified as one of the major environmental factors contributing to the higher T2D rates in ethnic minority populations [9]. Rising T2D prevalence rates among ethnic minority groups might therefore coincide with the increasing rates of overweight and obesity.

Despite a wealth of studies comparing ethnic minority groups with the host populations with regard to T2D and overweight and obesity, the extent of the differences in the various ethnic minority groups has not yet been systematically quantified. An up-to-date overview of the extent of the burden of T2D among the various ethnic groups might help identify the groups most at risk, and therefore guide policy makers. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was therefore to quantify the variation in T2D risk among populations of different geographical origin compared to the host European populations. In addition, we reviewed the co-occurrence of obesity with T2D among ethnic minority groups of different geographical origin.

Methods

Search strategy

MEDLINE (via PUBMED) and EMBASE (via Ovid) databases were systematically searched between January 1994 and April 2014 for all published papers or abstracts on T2D prevalence in ethnic minority groups in Europe. Eligibility criteria included studies written in English, conducted in an adult population (as per study criteria) from the general population, and compared ethnic minority groups with the host European population. The search terms were developed by an experienced medical librarian based on MeSH terms with input from the research group (Appendix). Subsequently, the PUBMED search terms were adapted to EMBASE criteria. Ethnicity search included terms such as “race,” “nationality,” or “migrant” as well as names of specific geographical regions. Names of all European countries and regions were included in the search term on Europe. For prevalence, MeSH terms on prevalence and epidemiology were included and terms on vital statistics. We also checked reference lists from primary studies and systematic reviews (snowballing) for finding any relevant study.

Study selection and analysis

Articles selected for full reading were included in the analysis if the article reported T2D prevalence, and the sample size was at least 50 participants for men and women each. We included articles in which the definition of T2D included previously diagnosed T2D cases (based on self-reported, registered at a hospital or other medical facility, by use of oral hypoglycemic drugs, or a combination of either of these), as well as articles that additionally included newly diagnosed T2D cases [based on fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)].

Articles were excluded when the ethnic group was not defined, or when conducted in a selective population such as hospital patients or pregnant women. When two or more articles had a data source in common, the article that most extensively presented the data was included.

Study selection was performed by one reviewer (DF) for all studies clearly meeting the inclusion or exclusion criteria. In case of uncertainty, inclusion of the study was decided upon by two reviewers (DF and KM). Data on demographics (age, gender, and ethnic group) and T2D (prevalence, diagnostic criteria) were extracted by two reviewers (KM and DF) independently into table format. In case of inconsistency of extracted data between both reviewers, the source article was checked. Additionally, reported obesity prevalence data were extracted.

Ethnicity can be defined in many different ways. Currently used definitions encompass characteristics such as shared origins and culture, traditions, common sense of identity, language or religious tradition, and the links with a particular geographical area. We defined ethnic groups primarily by geographical origin as per categorization of International Diabetes Federation (IDF) geographical regions [4] including South Asian (SA), Sub-Saharan African (SSA), Middle Eastern and North African (MENA), South and Central American (SCA), and Western Pacific (WP). IDF geographical region categorization was used to facilitate comparisons of T2D between the various ethnic minority groups and the prevalence in their respective geographical regions. South Asian comprised any ethnic group defined by the authors as South Asian or South East Asian as well as Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, or South Asian Surinamese. Sub-Saharan African origin comprised groups defined by the authors as “African descendant,” Sub-Saharan African, African-Caribbean, or “Black” Caribbean. Middle Eastern and North African comprised Turkish, Moroccan, North African, Syrian, Iraqi, Iranian, or “Other Middle Eastern.” South and Central American comprised Chileans and “Other South American.” Western Pacific comprised Vietnamese and Chinese. Data were pooled stratified by gender using a random-effect model in case of significant (p < 0.05) heterogeneity and fixed-effect model in case of non-significant (p > 0.05) heterogeneity. The I 2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity. Articles not reporting gender-stratified data were included in the total pooled data only. The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3.

Results

Study selection and description of included studies

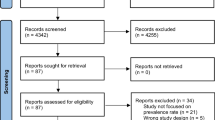

The search yielded 1840 hits on PUBMED and 33 on EMBASE, of which 30 were duplicates with PUBMED. After the assessment of titles and abstracts, 1797 records were further excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Among the 46 full-text articles that were assessed for eligibility, 30 articles were excluded because they met one or more exclusion criteria. Sixteen selected papers remained. Four articles were additionally included after the references’ search. Altogether, 20 articles were used in this meta-analysis (Table 1).

Flow chart of study selection according to the PRISMA Statement [23]

All 20 included articles were a sample from the general population, except one in which the target population included all office staff [10]. Seven articles reported obesity prevalence in addition to T2D prevalence [11–18]. Nine articles originated from the UK [3, 9, 15, 19–24], four from Sweden [11, 13, 17, 25], four from the Netherlands [16, 26–28], two from Norway [14, 15], and one from Denmark [29]. Thirteen studies used a random sampling selection method [11–14, 16–18, 26, 27, 30–33], six studies used a census [10, 25, 28, 29, 34, 35], and one a combination of both [15]. Ethnicity was defined according to self-reported or registered country of birth, self-reported ethnicity, or a combination of both. The age range varied widely among the studies.

Five studies included diagnosed T2D only using self-reported data or data from medical registrations [13, 15, 17, 18, 28]. Additionally to previously diagnosed T2D, the remainder of studies included one or more measurements to screen for newly diagnosed T2D in the study participants. Nine studies used the assessment of fasting blood glucose [10, 12, 14, 25–27, 31, 33, 35], four used HbA1c [14, 16, 29, 33], and nine an oral glucose tolerance test [10–12, 30–35].

South Asian origin populations

Twelve of the included articles presented data on SA populations (Table 1). All found higher T2D prevalence in SA compared to their host European population [10, 12, 14, 15, 18, 25, 26, 30–34] (Table 2). When the data were pooled, overall, SA had 3.7 (95 % CI 2.7–5.1) higher odds ratio for T2D compared to their European host populations (Fig. 2). In meta-analysis, we found Bangladeshis to have the highest odds ratio for T2D, (6.2, 95 % CI 3.9–9.8), followed by Pakistanis (5.4, 95 % CI 3.2–9.3) and Indians (4.1, 95 % CI 3.0–5.7) compared with Europeans (Fig. 3).

Seven studies presented data on SA stratified by gender [12, 14, 18, 25, 26, 30, 32]. Women had higher odds ratios for T2D (4.4, 95 % CI 3.1–6.3) than men (3.5, 95 % CI 2.5–4.7) (Fig. 2).

Sub-Saharan African origin populations

Eight studies provided data on SSA origin populations [10, 12, 18, 25–27, 31, 32], all showing a higher T2D prevalence in SSA than their local European counterparts (Table 2). When the data were pooled, SSA had 2.6 (95 % CI 2.0–3.5) higher odds ratios for T2D than their European counterparts (Fig. 4).

Of the six SSA-included studies, all reported gender-stratified data except one. Higher pooled odds ratios for T2D were observed in women (3.2, 95 % CI 2.2–4.7) than in men (2.2, 95 % CI 1.6–2.8).

Middle Eastern and North African origin populations

All eight studies among MENA origin populations reported higher T2D prevalence among these populations than among European origin populations (Table 2) [11, 13, 15–17, 25, 28, 29]. MENA origin had 2.7 (95 % CI 1.8–3.9) higher pooled odds ratios for T2D than their local European populations (Fig. 5).

Five studies reported prevalence for men and women separately [13, 17, 25, 28, 29]. Out of these, higher prevalence among women was reported for the subgroups of Moroccan, Iraqi, Syrian, and Turkish in three out of four studies that included Turkish origin participants. A more than 10 percentage point higher prevalence in women than men was found among North Africans [25]. In Lebanese and Iranians, higher prevalence rates were reported for men compared with women. The pooled odds ratios for T2D were 2.1 (95 % CI 1.3–3.5) in MENA men and 3.9 (95 % CI 2.2–6.8) in MENA women.

South and Central American origin populations

The two studies that included data on SCA origin populations were both carried out in Sweden (Table 2). One reported a slightly higher prevalence among Swedish than Chilean, while the other found a higher prevalence in Chilean and other South American than in Swedish [13, 25]. SCA origin had overall 1.3 (95 % CI 1.1–1.6) higher odds ratios for T2D than their Swedish local population (Fig. 6). SCA women had similar odds ratios for T2D (1.2, 95 % CI 0.9–1.6), but men had higher odds ratios (1.4, 95 % CI 1.1–1.8) compared with the local European population.

Western Pacific origin populations

Three studies reported data on WP populations [15, 18, 35]. Both in Chinese [18, 35] and Vietnamese origins [15], higher prevalence was reported. When these data were pooled, WP had 2.3 higher odds ratios for T2D than the European population (95 % CI 1.2–4.1) (Fig. 7).

Differences in T2D prevalence between men and women were small. When combined, men had 1.6 (95 % CI 1.1–2.4) higher odds ratios and women had 1.8 (95 % CI 1.1–3.1) higher odds ratios for T2D than the British local population.

Co-occurrence obesity with type 2 diabetes

Seven papers reported obesity prevalence according to BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [11–14, 16–18] (Table 2).

In SA, the pattern of prevalence of obesity across populations differed from the pattern for T2D prevalence. While among all SA groups a higher T2D prevalence was reported than among Europeans, obesity was lower in Bangladeshis [18, 30] and South Asians as defined by Cappuccio et al. [12], higher in Pakistanis [18, 30], and similar in South Asians as defined by Jenum et al. [14]. Among Indians, Bhopal et al. [30] reported a higher obesity prevalence compared to Europeans, while Zaninotto et al. [18] reported a lower obesity prevalence than among Europeans. Overall, women of SA origin had a higher obesity prevalence than men. However, women did not have consistently higher T2D prevalence than men. Zaninotto et al. reported a higher T2D prevalence among Indian and Bangladeshi men compared to women, despite higher obesity prevalence in women [18]. Among Pakistanis and South Asians defined by Jenum et al., a higher T2D prevalence was observed in women as well as a higher obesity prevalence than in men [14].

In contrast, for the African and Middle Eastern populations, we find corresponding patterns of obesity and T2D. The obesity prevalence is higher among African-Caribbeans, Iraqis, Turks, and Moroccans than among Europeans in line with a higher T2D prevalence both overall and for men and women separately [11, 13, 16–18]. Only among Iranians resident in Sweden, a slightly lower obesity prevalence is observed among Iranians compared to Swedish, while T2D prevalence is higher in Iranians than in Swedish [13].

For SCA and WP origin, the pattern of obesity and T2D was reversed in the two studies that reported on both outcome measures [18].

Discussion

Key findings

All ethnic minority groups had higher prevalence and higher odds ratios for T2D than their host European populations. SA origin had the highest odds ratio, followed by MENA origin, SSA origin, WP origin, and SCA origin, respectively. Except for SCA, the odds ratios were higher in women than in men. We find important differences within SA populations among which the highest odds ratios for T2D are observed among Bangladeshis. There is concurrence between T2D and obesity among SSA origin and MENA origin. Among SA, SCA, and WP origins, no clear concurrence pattern is found.

Discussion of the key findings

This meta-analysis shows that the extent of the T2D burden differs by geographical origin. While all ethnic minority groups are more affected by T2D compared to Europeans, SA, MENA, and SSA origins are more affected than West Pacific and SCA origin populations.

The observed differences between geographical origin populations are possibly a reflection of the differences in T2D prevalence between these geographical regions. Differing biological, contextual, and specific risk factors between the regions can contribute to differences in T2D prevalence between these populations. For example, the genetic susceptibility for T2D differs between populations. Some T2D-associated polymorphisms are more common in SA than in Europeans [36]. Despite identification of some promising genetic variants, however, the genetic basis of T2D remains unclear [37].

Differences in T2D prevalence between geographical regions of origin can only explain part of the variation between populations originating from these regions in Europe. Our findings are not completely consistent with T2D prevalence rates reported for the IDF geographical regions. Among the IDF geographical regions, the prevalence is highest in the MENA region (10.9 %), followed by SA (8.7 %), SCA (8.2 %), and WP (8.1 %) with SSA (5.7 %) having the lowest prevalence [4]. The prevalence in SSA region is far lower compared to the high prevalence found among this group in Europe. Undiagnosed T2D may be higher in this region than other regions, which might contribute to the low prevalence rate reported in SSA. [4] Nevertheless, studies, comparing SSA migrants with their compatriots in rural and urban SSA, show a far higher T2D prevalence among the same ethnic group in Europe than in SSA [38]. The high prevalence of T2D among SSA origin populations in Europe may reflect the potential risk for T2D in the SSA region. Additionally, differences between populations may arise as a consequence of differential national contextual factors. For example, ethnic minority groups may obtain a different socio-economic position than in their country of origin or adapt dietary changes after migration that may have a differential effect between ethnic minority groups. Chinese living in China report less energy intake from carbohydrates, and also more physical activity than Chinese resident in the US [39]. Unhealthy dietary changes after migration have also been observed among SSA in Australia [40]. Abouzeid et al. demonstrate that the effects of socio-economic status (SES) on T2D prevalence differ by geographical region of origin [19]. T2D prevalence is three to five percentage points lower among MENA origin in the highest SES quintile compared to those in the lowest [19]. For those of WP origin, prevalence is similar over all SES quintiles. A differential effect of SES on T2D prevalence may therefore contribute to differences in T2D odds observed between geographical origin populations. Nevertheless, some studies show that ethnic differences in the prevalence of T2D remain even adjusted for SES, suggesting that other factors such as genetic predispositions might be relevant [19, 41]. In this meta-analysis, we cannot ascertain the contribution of contextual factors, because too few studies report type 2 diabetes prevalence stratified by factors such as age and socio-economic status to be able to stratify in the meta-analysis.

We also observe large differences within populations originating from one geographical region. We observe especially large differences in the co-occurrence of obesity and T2D among SA subgroups. Bangladeshis have the highest T2D odds compared to Pakistanis and Indians, while they have lower obesity prevalence even compared to Europeans. The included studies did not report ethnic-specific BMI cut-offs for SA origin, which could possibly explain the lack of concurrence. Nevertheless, the lack of concurrence is consistent with other studies showing that obesity accounts only partly for differences in T2D between ethnic groups [16, 27, 42]. A large heterogeneity between SA origin populations has also been observed for other health outcomes such as high blood pressure and other cardiovascular diseases [43]. In Agyemang and Bhopal [44] systematic review, for example, blood pressure levels are slightly higher in Indians, slightly lower in Pakistanis, and much lower in Bangladeshis compared with European local population in the UK. The huge differences in the prevalence of T2D among the SA subgroups emphasize the importance of studying SA groups separately rather than combining them.

Limitations

Studies used different diagnostic methods and cut-offs for T2D that may have affected our study results. Because of this, we used the random-effects model in our analyses when heterogeneity was significant, which is a more conservative approach for estimating differences as compared with the fixed-effect model. Also, diagnostic methods are somewhat similar across studies. Notwithstanding, consistent high prevalence rates are observed in all studies and therefore unlikely to affect our key study conclusions.

We grouped the ethnic minority groups per IDF geographical categorization to shed light on how these populations in Europe are compared with people in their geographical origins. We are aware of the important differences within these broad IDF categories, which might affect our study conclusions. Nonetheless, we also present results on individual studies, which provide further opportunity to assess the differences within IDF geographical regions.

The search performed resulted in articles mainly originating from Western and Northern European countries. No articles on South or Eastern European countries were found. Considering the large differences in diabetes prevalence between European countries, our findings should therefore be interpreted with caution for these other European regions.

The studies span about 20 years, which may potentially affect the comparability and interpretability of the results. However, considering the consistency between studies reporting more T2D among ethnic minority groups compared to European, the observed ethnic differences are likely unaffected.

Conclusions and implications

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis show that the prevalence of T2D varies between populations of different geographical origins. SA origin has three to five times higher odds ratios for T2D compared to European populations, and MENAs have two to four times higher odds ratios. Even though SSA origin is less studied in comparison to other ethnic minority groups, in particular SA, their odds ratios for T2D are also two to three times higher. This calls for attention to SSA origin populations in future research and interventions. Differences in T2D prevalence between regions of origin only explain part of the differences in T2D between populations originating from those regions in Europe. Research comparing ethnic minority populations in Europe with compatriots who have not migrated such as the RODAM study (http://www.rod-am.eu/home) may shed light on the causes of T2D in ethnic minorities. [45] Furthermore, future research studying the causes of T2D in ethnic minority populations should take the interethnic differences into account.

References

Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H (2004) Global prevalence of diabetes estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 27(5):1047–1053

Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Eberhardt MS, Flegal KM, Engelgau MM, Saydah SH, Williams DE, Geiss LS, Gregg EW (2006) Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the US Population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care 29(6):1263–1268. doi:10.2337/dc06-0062

Imkampe AK, Gulliford MC (2011) Increasing socio-economic inequality in type 2 diabetes prevalence–repeated cross-sectional surveys in England 1994–2006. Eur J Pub Health 21(4):484–490. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq106

Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J (2011) IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 94(3):311–321

Agyemang C, Addo J, Bhopal R, de Graft Aikins A, Stronks K (2009) Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and established risk factors among populations of sub-Saharan African descent in Europe: a literature review. Glob Health 5(7):1

Uitewaal P, Manna D, Bruijnzeels M, Hoes A, Thomas S (2004) Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, other cardiovascular risk factors, and cardiovascular disease in Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in North West Europe: a systematic review. Prev Med 39(6):1068–1076

Lanzieri G (2011) Fewer, older and multicultural? Projections of the EU populations by foreign/national background (trans: Eurostat)

Oldroyd J, Banerjee M, Heald A, Cruickshank K (2005) Diabetes and ethnic minorities. Postgrad Med J 81(958):486–490

Seidell JC (2000) Obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes—a worldwide epidemic. Br J Nutr 83(S1):S5–S8

Whitty CJ, Brunner EJ, Shipley MJ, Hemingway H, Marmot MG (1999) Differences in biological risk factors for cardiovascular disease between three ethnic groups in the Whitehall II study. Atherosclerosis 142(2):279–286

Bennet L, Johansson SE, Agardh CD, Groop L, Sundquist J, Rastam L, Sundquist K (2011) High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Iraqi and Swedish residents in a deprived Swedish neighbourhood–a population based study. BMC Public Health 11:303. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-303.

Cappuccio FP, Cook DG, Atkinson RW, Strazzullo P (1997) Prevalence, detection, and management of cardiovascular risk factors in different ethnic groups in south London. Heart 78(6):555–563

Gadd M, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, Wandell P (2005) Do immigrants have an increased prevalence of unhealthy behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 12(6):535–541

Jenum AK, Holme I, Graff-Iversen S, Birkeland KI (2005) Ethnicity and sex are strong determinants of diabetes in an urban Western society: implications for prevention. Diabetologia 48(3):435–439. doi:10.1007/s00125-005-1668-8.

Tran AT, Straand J, Diep LM, Meyer HE, Birkeland KI, Jenum AK (2011) Cardiovascular disease by diabetes status in five ethnic minority groups compared to ethnic Norwegians. BMC Public Health 11:554. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-554.

Ujcic-Voortman JK, Schram MT, Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, Verhoeff AP, Baan CA (2009) Diabetes prevalence and risk factors among ethnic minorities. Eur J Public Health 19(5):511–515. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp096.

Wandell PE, Hjorleifsdottir Steiner K, Johansson SE (2003) Diabetes mellitus in Turkish immigrants in Sweden. Diabetes Metab 29(4 Pt 1):435–439

Zaninotto P, Mindell J, Hirani V (2007) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among ethnic groups: results from the Health Surveys for England. Atherosclerosis 195(1):e48–e57. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.017.

Abouzeid M, Philpot B, Janus ED, Coates MJ, Dunbar JA (2013) Type 2 diabetes prevalence varies by socio-economic status within and between migrant groups: analysis and implications for Australia. BMC Public Health 13(1):252

Cauchi S, El Achhab Y, Choquet H, Dina C, Krempler F, Weitgasser R, Nejjari C, Patsch W, Chikri M, Meyre D (2007) TCF7L2 is reproducibly associated with type 2 diabetes in various ethnic groups: a global meta-analysis. J Mol Med 85(7):777–782

Hu FB (2011) Globalization of Diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care 34(6):1249–1257. doi:10.2337/dc11-0442.

McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ (2004) Type 2 diabetes prevalence in Asian Americans results of a national health survey. Diabetes Care 27(1):66–69

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Roberts A, Cash TF, Feingold A, Johnson BT (2006) Are black-white differences in females’ body dissatisfaction decreasing? A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 74(6):1121

Carlsson AC, Wandell PE, Hedlund E, Walldius G, Nordqvist T, Jungner I, Hammar N (2013) Country of birth-specific and gender differences in prevalence of diabetes in Sweden. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 100(3):404–408. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2013.03.014.

Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, Anujuo K, Zaninotto P, Nazroo J, Nicolaou M, Unwin N, van Valkengoed I, Redekop WK (2011) Diabetes prevalence in populations of South Asian Indian and African origins: a comparison of England and the Netherlands. Epidemiology 22(4):563–567

Meeks K, Beune E, Snijder M, Peters R, Stronks K, Agyemang C (2014) Type II diabetes among Ghanaian residents in the Netherlands; how do they compare with other ethnic groups? The HELIUS study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103:S2

Weijers RN, Bekedam DJ, Oosting H (1998) The prevalence of type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus in an inner city multi-ethnic population. Eur J Epidemiol 14(7):693–699

Kristensen JK, Bak JF, Wittrup I, Lauritzen T (2007) Diabetes prevalence and quality of diabetes care among Lebanese or Turkish immigrants compared to a native Danish population. Primary Care Diabetes 1(3):159–165. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2007.07.007.

Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Yallop J, Walker L, Alberti KG, Harland J, Patel S, Ahmad N, Turner C, Watson B, Kaur D, Kulkarni A, Laker M, Tavridou A (1999) Heterogeneity of coronary heart disease risk factors in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and European origin populations: cross sectional study. BMJ 319(7204):215–220

Riste L, Khan F, Cruickshank K (2001) High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in all ethnic groups, including Europeans, in a British inner city: relative poverty, history, inactivity, or 21st century Europe? Diabetes Care 24(8):1377–1383

Tillin T, Hughes AD, Mayet J, Whincup P, Sattar N, Forouhi NG, McKeigue PM, Chaturvedi N (2013) The relationship between metabolic risk factors and incident cardiovascular disease in Europeans, South Asians, and African Caribbeans: SABRE (Southall and Brent Revisited)—a prospective population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 61(17):1777–1786. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.046.

Webb DR, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Srinivasan B, Taub N, Campbell S, Barnett J, Farooqi A, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Davies MJ (2011) Screening for diabetes using an oral glucose tolerance test within a western multi-ethnic population identifies modifiable cardiovascular risk: the ADDITION-Leicester study. Diabetologia 54(9):2237–2246. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2189-2.

Davies MJ, Ammari F, Sherriff C, Burden ML, Gujral J, Burden AC (1999) Screening for Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the UK Indo-Asian population. Diabetic Med 16(2):131–137

Unwin N, Harland J, White M, Bhopal R, Winocour P, Stephenson P, Watson W, Turner C, Alberti KG (1997) Body mass index, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and glucose intolerance in Chinese and Europid adults in Newcastle, UK. J Epidemiol Community Health 51(2):160–166

Kooner JS, Saleheen D, Sim X, Sehmi J, Zhang W, Frossard P, Been LF, Chia K-S, Dimas AS, Hassanali N, Jafar T, Jowett JBM, Li X, Radha V, Rees SD, Takeuchi F, Young R, Aung T, Basit A, Chidambaram M, Das D, Grundberg E, Hedman AK, Hydrie ZI, Islam M, Khor C-C, Kowlessur S, Kristensen MM, Liju S, Lim W-Y, Matthews DR, Liu J, Morris AP, Nica AC, Pinidiyapathirage JM, Prokopenko I, Rasheed A, Samuel M, Shah N, Shera AS, Small KS, Suo C, Wickremasinghe AR, Wong TY, Yang M, Zhang F, Abecasis GR, Barnett AH, Caulfield M, Deloukas P, Frayling TM, Froguel P, Kato N, Katulanda P, Kelly MA, Liang J, Mohan V, Sanghera DK, Scott J, Seielstad M, Zimmet PZ, Elliott P, Teo YY, McCarthy MI, Danesh J, Tai ES, Chambers JC (2011) Genome-wide association study in individuals of South Asian ancestry identifies six new type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 43 (10):984–989

Carulli L, Rondinella S, Lombardini S, Canedi I, Loria P, Carulli N (2005) Review article: diabetes, genetics and ethnicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 22:16–19. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02588.x.

Mbanya J, Cruickshank JK, Forrester T, Balkau B, Ngogang JY, Riste L, Forhan A, Anderson N, Bennett F, Wilks R (1999) Standardized comparison of glucose intolerance in west African-origin populations of rural and urban Cameroon, Jamaica, and Caribbean migrants to Britain. Diabetes Care 22(3):434–440

Lee MM, Wu-Williams A, Whittemore AS, Zheng S, Gallagher R, Teh C-Z, Zhou L, Wang X, Chen K, Ling C (1994) Comparison of dietary habits, physical activity and body size among Chinese in North America and China. Int J Epidemiol 23(5):984–990

Renzaho AMN, Burns C (2006) Post-migration food habits of sub-Saharan African migrants in Victoria: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Diet 63(2):91–102. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0080.2006.00055.x.

Shamshirgaran SM, Jorm L, Bambrick H, Hennessy A (2013) Independent roles of country of birth and socioeconomic status in the occurrence of type 2 diabetes. BMC Public Health 13(1):1223

Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hu FB (2006) Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of Type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care 29(7):1585–1590. doi:10.2337/dc06-0057.

Oza-Frank R, Ali MK, Vaccarino V, Narayan KV (2009) Asian Americans: diabetes prevalence across US and World Health Organization weight classifications. Diabetes Care 32(9):1644–1646

Agyemang C, Bhopal R (2002) Is the blood pressure of South Asian adults in the UK higher or lower than that in European white adults? A review of cross-sectional data. J Hum Hypertens 16(11):739–51

Agyemang C, Beune E, Meeks K, Owusu-Dabo E, Agyei-Baffour P, Aikins Ad-G, Dodoo F, Smeeth L, Addo J, Mockenhaupt FP (2015) Rationale and cross-sectional study design of the research on obesity and type 2 Diabetes among African Migrants: the RODAM study. BMJ Open 4(3):e004877. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004877.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support received from Science Without Borders (SWG-122/2012) Brazil, for the work of D. Freitas-Da-Silva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human and animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

None.

Appendix: Search terms used in MEDLINE

Appendix: Search terms used in MEDLINE

Ethnic minority groups | ethnic group[tiab] OR group, ethnic[MeSh Terms] OR nationality*[tiab] OR ethnicity[tiab] OR race[tiab] OR racial stock[tiab] OR migrant*[tiab] OR ethnic minority group[tiab] OR non-western migrants[tiab] OR african*[tiab] OR north african*[tiab] OR arab[tiab] OR arabs[tiab] OR arabic[tiab] OR african*[tiab] OR west african*[tiab] OR black[tiab] OR black african*[tiab] OR south sahara african*[tiab] OR moroccan*[tiab] OR somali*[tiab] OR ethiopian*[tiab] OR sudanese*[tiab] OR ghanaian*[tiab] OR sub-sahara african*[tiab] OR afro-arab*[tiab] OR maghrebin*[tiab] OR harki*[tiab] OR asian*[tiab] OR south asian*[tiab] OR east asian*[tiab] OR middle east asian*[tiab] OR turkish*[tiab] OR turk*[tiab] OR indian*[tiab] OR pakistani*[tiab] OR bangladeshi*[tiab] OR palestinian*[tiab] OR syrian*[tiab] OR lebanese*[tiab] OR yemeni*[tiab] OR egyptian*[tiab] OR iraqi*[tiab] OR jordanian*[tiab] OR vietnamese*[tiab] OR iranian*[tiab] OR kurd*[tiab] OR chinese*[tiab] OR japanese*[tiab] OR jew*[tiab] OR muslim*[tiab] OR sri lankan*[tiab] OR oceanian*[tiab] OR oceanic*[tiab] OR australian*[tiab] OR new zealander*[tiab] OR kiwi*[tiab] OR indonesian*[tiab] OR north american*[tiab] OR central american*[tiab] OR south american*[tiab] OR hispanic*[tiab] OR Caribbean*[tiab] OR african caribbean*[tiab] OR african-caribbean*[tiab] OR white caribbean*[tiab] OR black caribbean*[tiab] OR surinamese*[tiab] OR surinaam*[tiab] OR antillean*[tiab] OR aruban*[tiab] OR mexican*[tiab] OR mexican–american*[tiab] OR chilean*[tiab] OR argentinian*[tiab] OR american*[tiab] OR canadian*[tiab] OR brazilian*[tiab] OR us american*[tiab] OR inuit*[tiab] OR asian caribbean*[tiab] OR african caribbean*[tiab] OR african-caribbean*[tiab] |

Europe | europe OR southern europe OR western europe OR northern europe OR albania OR andorra OR armenia OR austria OR azerbaijan OR belarus OR belgium OR bosnia and herzegovina OR bulgaria OR croatia OR cyprus OR czech republic OR denmark OR estonia OR finland OR france OR georgia OR germany OR greece OR hungary OR iceland OR ireland OR italy OR kosovo OR latvia OR liechtenstein OR lithuania OR luxembourg OR macedonia OR malta OR moldova OR monaco OR montenegro OR netherlands OR norway OR poland OR portugal OR romania OR russia OR san marino OR serbia OR slovakia OR slovenia OR spain OR sweden OR switzerland OR the former yugoslav republic of macedonia OR turkey OR ukraine OR united kingdom |

Type 2 diabetes | diabetes[tiab] OR diabetes mellitus[tiab] OR noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus[tiab] OR niddm[tiab] OR type 2 diabetes mellitus[tiab] OR oral glucose tolerance test[tiab] OR ogtt[tiab] OR venous plasma glucose[tiab] OR fasting glucose[tiab] |

Prevalence data | vital statistics OR vital statistics registration OR morbidity OR prevalence[mesh] OR prevalence [tw] OR epidemiology[sh] OR epidemiologic studies[mesh terms] NOT (case–control study OR case–control studies OR seroepidemiologic study OR seroepidemiologic studies) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meeks, K.A.C., Freitas-Da-Silva, D., Adeyemo, A. et al. Disparities in type 2 diabetes prevalence among ethnic minority groups resident in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med 11, 327–340 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1302-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1302-9