Abstract

One of the roles of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) is to provide guidance on the management of patients seeking surgery for adiposity-based chronic diseases. The role of endoscopy around the time of endoscopy is an area of clinical controversy. In 2018, IFSO commissioned a task force to determine the role of endoscopy before and after surgery for the management of adiposity and adiposity-based chronic diseases. The following position statement is issued by the IFSO Endoscopy in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Taskforce. It has been approved by the IFSO Scientific Committee and Executive Board. This statement is based on current clinical knowledge, expert opinion, and published peer-reviewed scientific evidence. It will be reviewed regularly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Preamble

The International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) has played an integral role in educating both the metabolic surgical and the medical community about the best management of patients who have undergone surgery for adiposity-based chronic diseases.

The role of endoscopy around the time of bariatric surgery is currently an area of clinical controversy.

In 2018, IFSO commissioned a task force (Appendix 1) to determine if routine endoscopy should be undertaken prior to and after surgery for the management of adiposity and adiposity-based chronic diseases.

The following position statement is issued by the IFSO Endoscopy in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Taskforce and has been approved by the IFSO Scientific Committee and Executive Board. This statement is based on current clinical knowledge, expert opinion, and published peer-reviewed scientific evidence. It will be reviewed on a regular basis.

Background

Surgery is considered to be the most effective and durable treatment for adiposity-based chronic diseases for individuals with more severe classifications of obesity. These procedures not only provide substantial weight loss but also improve health, well-being and increase longevity [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

The number of bariatric/metabolic procedures being performed world-wide is increasing each year. According to the latest IFSO survey, there were 191,326 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); 340,550 longitudinal sleeve gastrectomy (LSG); 19,332 adjustable gastric bands (AGB), 30,563 one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB); and 685 single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy/one anastomosis duodenal switch (SADI-S/OADS) procedures performed globally in 2017 [9].

Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) is a procedure that allows for visual inspection of the lumen and provides access for biopsying the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. EGD is an important investigative tool for the diagnosis of diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract including hiatal hernias (HH), esophageal mucosal injury secondary to gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett’s esophagus (BE), gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC).

Whilst the ultimate decision to perform an EGD lies with the treating physician, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians currently recommend that screening EGD should not be routinely recommended for heartburn symptoms in isolation in women of any age or for men aged < 50 years. Their recommendations are summarized in Table 1 [10].

A combined statement from the American College of Gastroenterology and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recommends that patients experiencing dyspepsia undergo EGD when they are aged > 60 to exclude upper gastrointestinal neoplasia [11].

It is currently unknown under which specific circumstances, in addition to the above, should an EGD be obtained in patients seeking bariatric surgery. Areas of controversy include if patients with no symptoms should have an EGD and how different EGD findings may impact surgical procedure choice and outcomes.

EGD prior to bariatric surgery allows for the diagnosis of concomitant diseases that may preclude bariatric surgery, such as upper gastrointestinal malignancies or varices due to portal hypertension. It may also lead to the diagnosis of diseases that should be treated prior to surgery, such as peptic ulcer disease and helicobacter pylori infection. EGD also allows for the diagnosis of conditions such as GERD-related esophageal mucosal injury including erosive esophagitis, esophageal ulcers, strictures and BE; and anatomical defects such as HH, which may influence the operative procedural choice [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In addition, EGD allows for a pre-operative assessment of the distal stomach which becomes inaccessible after OAGB and RYGB.

For these reasons, some bariatric surgery centres perform routine EGD prior to any bariatric procedure, independent of symptoms. A recent systematic review noted that only 7.6% of EGD performed prior to bariatric surgery demonstrated findings that led to a change in operative management [19]. This low yield rate arguably makes it difficult to justify the practice of routine screening on the basis of increased costs, possible complications of EGD and uncertainty about the potential impact on outcomes. However, in the same review, 20.6% of patients was noted to have esophagitis, a finding that may become important in view of the current high utilization of LSG, a procedure which is generally considered to contribute to GERD and esophageal mucosal injury [14, 20,21,22,23,24]. An evidence-based practice guideline would help to fill this knowledge gap; however, none is currently available.

Whilst most would agree that EGD is clearly indicated as a part of the management pathway after bariatric surgery when there are symptoms suggesting GERD, BE, EAC or complications of the procedure such as fistulae, ulcers or volume reflux, the role of routine surveillance EGD is less well defined. The anatomical changes created at the time of some bariatric surgical procedures place patients at increased risk of GERD [12,13,14,15,16,17,18], BE [22, 23] and bile reflux [24, 25], which in turn, theoretically place patients at a higher risk to develop upper gastrointestinal malignancy. Additionally, patient symptoms may not be a reliable guide for the development or progression of these diseases [22]. Again, there are currently no evidence-based guidelines to help guide practice.

As the routine use of screening EGD before and surveillance after bariatric surgery is controversial, IFSO commissioned its Scientific Committee to perform a literature review and forward recommendations regarding a position statement to the Executive Board for approval.

Methods

Literature Search

We performed a comprehensive literature search to identify studies reporting outcomes of EGD performed before and after any bariatric procedure. The search was done in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. We searched MEDLINE (1946 to 26 August 2019), EMBASE (1974 to 26 August 2019), PubMed (until 26 August 2019) and the Cochrane Library (until 26 August 2019). Search terms were broad, to encompass all possible procedures. These included terms specifying the endoscopic procedure (endoscopy, gastroscopy, esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy, upper GI endoscopy) and the bariatric procedure (gastric band, sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, mini gastric bypass, one anastomosis gastric bypass, bariatric surgery), single anastomosis (single anastomosis, loop anastomosis, one anastomosis, omega loop, mini). A full list of search terms is presented in Tables 10 and 11. Manual searching of reference lists from reviews, as well as references from selected primary studies, was performed to identify any additional studies.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were selected that reported on findings and changes in management relating to EGD before and after bariatric surgery. All comparative study designs were accepted. We summarized data for studies with greater than 15 adult participants, with all follow-up time frames. Only full text articles were included. Studies with no pre-operative gastroscopy performed or only reports on one specific gastroscopy findings were excluded.

Data Extraction

Information extracted from eligible studies included basic study data (year, country, design, study size), demographic data, surgical technique, follow-up, endoscopic findings and complications.

Results

Literature Search

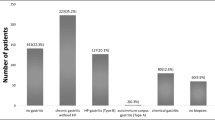

Using the search strategy described, we identified 18,947 studies. After 8678 duplicates were removed, we screened titles and abstracts for 10,269 records. Full text articles for 217 eligible studies were screened, and 154 articles were subsequently excluded. There were 63 full length publications involving 22,495 patients that were identified for inclusion (Fig. 1). The included studies are summarized in Table 2.

EGD Prior to Bariatric Surgery

There were 63 studies involving 22,495 patients reporting on the observed incidence of abnormal findings at EGD in patients planning to have bariatric surgery. The mean percentage of patients with at least one abnormal finding reported in each study ranged from 4.6–89.7% (Tables 2 and 3), with a total of 10,531 patients (55.5% of 18,961 patients) having at least one abnormal finding (Table 3).

The most commonly reported abnormal finding was gastritis. There were 39 papers involving 4345 patients that reported this finding, with the mean percentage of patients affected per paper ranging from 3.0–88.3% (mean 31.8%, pooled mean 19.3%). There were 56 studies that reported HH including 4420 patients. The mean percentage of patients with HH ranged from 0.6–90.2% (mean 23.5%. pooled mean 19.6%). BE was reported in 31 papers including 231 patients. The mean percentage of patients affected ranged from 0.1–9.9% (mean 2.3%, pooled mean 1.0%) (Table 3).

There were eleven studies (Table 4, 7001 patients) that classified their EGD findings based on the presence or absence of patients’ pre-operative symptoms. The mean percentage of symptomatic patients in these studies ranged from 12.1 to 59.6% (mean 32.0%, pooled mean 20.7%). Considering the symptomatic population, there was a mean of 16.0% patients with at least one abnormal finding in their pre-operative EGD (range 7.2–34.1%, pooled mean 15.2%). By way of comparison, abnormal EGD findings were found in a mean of 25.3% of patients with no pre-operative symptoms (range 2.1–63.8%, pooled mean 15.4%).

There were 30 studies involving 15,177 patients that reported on management changes following the pre-operative EGD (Tables 5, 6 and 7). A change in planned surgical management on the basis of an abnormal finding at EGD was reported in 2545 patients (16.8%) (Tables 5, 6 and 7). Gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection and HH were the most common reasons for changing the intended surgical plan (Tables 5, 6 and 7).

Endoscopic findings from these 30 studies were then stratified according to their impact on management (Tables 5 and 8):

-

Group 1—normal EGD with no change in management n = 6171 patients (40.7%)

-

Group 2—abnormal EGD findings that did not result in a change in management n = 5432 (35.8%)

-

Group 3—abnormal EGD findings that led to a change in surgical approach or led to a delay in surgical management n = 2511 (16.5%)

-

Group 4—abnormal EGD finding that were a contraindication to bariatric surgery n = 34 (0.2%).

The types of conditions that were included in each group are summarized in Table 8.

Only two out of these 30 studies reported on patients’ symptoms. In one study, 68% of patients in Group 3 had upper gastrointestinal symptoms [21], and in the other, 78.9% of patients had symptoms [51].

EGD Following Bariatric Surgery

There were eleven studies identified that compared the findings before and after bariatric procedures (n = 1243), with eight prospective studies (n = 555) on AGB and LSG (Table 9).

Following AGB, there was an increase in esophagitis in two studies (n = 44) [48, 49]. There was one study that reported a 39.1% incidence of proximal pouch dilatation at 6 months follow-up (n = 26). Of note, these patients were all symptomatic.

Following RYGB, two studies reported a reduction in pre-operative upper gastrointestinal pathology. Czeczko et al. reported resolution of pre-operative gastritis and hiatal hernia and a reduction of non-erosive gastritis and esophagitis (n = 110) [66]. In contrast, Teivelis et al. reported reduction in gastritis but not esophagitis (n = 42) [71]. Complications of RYGB were reported in three studies [66, 71, 87]. These patients were typically symptomatic.

There were 5 studies reporting pre- and post-operative changes following LSG. In one study, the rates of all grades of esophagitis were increased post-operatively with up to 53% de novo esophagitis [84]. However, another study reported improvement in esophagitis severity in 19% of patients [79].

The de novo incidence of BE in the three reports currently available was 15% [23], 17.2% [22] and 18.8% [20] respectively. Importantly, in these series, a significant proportion of patients who developed BE after LSG were asymptomatic [20, 22, 23].

Discussion

The need for endoscopic inspection of the upper gastrointestinal tract before and after bariatric surgery is an ongoing area of controversy.

This systematic review of the available literature suggests that abnormal EGD findings are likely to be found in at least 55.5% of patients prior to bariatric surgery. The most common abnormal findings were gastritis, HH and esophagitis. Conditions that would lead to the modification or delay of surgery were found less commonly, with 16.5% having findings that led to modification or delay of the planned procedure, and 0.2% having surgery cancelled (Table 8).

If pre-operative EGD is limited to only those with symptoms, there is a small but potentially clinically significant risk of missing conditions that may preclude surgery or lead to a modification of a surgical plan. The current data is difficult to interpret due to its heterogeneous nature; however, a pooled mean of 25.3% of asymptomatic patients had abnormal EGD findings (Table 4). Whilst there is no information on how these findings changed management, the frequency of abnormal findings may justify the routine use of pre-operative endoscopy. This is particularly so in regions where the background incidence of significant gastric and esophageal pathology is high, for example Asian populations [88, 89].

Due to the varying effect of the different bariatric procedures on GERD, bile reflux, BE and malignancy risk, it may be appropriate to tailor the decision regarding EGD according to the procedure planned with EGD recommended routinely for procedures with a risk for bile reflux such as LSG and OAGB and based on symptoms for LAGB and RYGB; however, there is no currently available evidence to support such a stratified approach.

There is limited information on the yield from routine EGD following bariatric surgery. The available studies suggest that there is a change in the pre-operative pathology detected, as well as an incidence of new pathology regardless of the bariatric procedure performed.

In the LAGB and RYGB series, the correlation between symptoms and pathology appears to be high; however, the lack of data in asymptomatic patients is a major potential cause of bias. On balance, it would seem reasonable that EGD only be offered to symptomatic patients after these procedures [48, 49, 66, 71, 87].

Three studies following LSG have shown a poor correlation between GERD symptoms, degree of esophagitis severity and the development of de novo Barret’s esophagus [20, 22, 23]. These studies suggest that if EGD is only performed in patients with upper GI symptoms following LSG, we will potentially miss the opportunity to diagnose BE and intervene before the disease progresses. Most recommendations for patients with Barrett’s metaplasia suggest 2–3 yearly surveillance EGD [90]. Given the lack of data specific to the post-LSG situation, it may be that the higher risk of BE after LSG mandates a similar approach.

There was no information available on the EGD findings after OAGB. There is a theoretical concern of upper GI cancers on the basis of bile reflux; however, to date there has been only one case report of an esophageal adenocarcinoma 2 years after surgery [91]. Given this theoretical risk, it may be reasonable to survey patients who have undergone an OAGB on a similar protocol to the BE recommendations whilst more data accrues.

There are significant limitations to these current data. Many studies are of lesser quality being retrospective reports rather than purposeful prospective trials. There is limited post-operative information available for all procedures and none for OAGB. It is likely that there has been an under-reporting of most endoscopic findings with negative findings not documented in the majority of papers. There is also a risk of observation bias between endoscopists and differing definitions of conditions such as BE. There is no consistency in the way bariatric procedures are performed. Reporting of results is heterogeneous and not standardized making comparison difficult.

The need for more prospective studies and RCT’s is paramount to our understanding of our interventions. However, in the absence of definitive evidence, the need for guidance in areas of controversy is the responsibility of organizations, such as IFSO. Though position statements are not without bias, they are meant to be temporal in nature. Continued re-analysis is necessary in order to remain relevant, and according to the IFSO position statement on position statements, this position statement will be reviewed regularly.

Recommendations of the IFSO Endoscopy in Bariatric Surgery Taskforce

Based on the existing data we recommend the following:

-

1.

Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) should be considered for all patients with upper GI symptoms planning to undergo a bariatric procedure due to the frequency of pathology that may alter management.

-

2.

EGD should be considered for patients without upper GI symptoms who are planning to undergo a bariatric procedure due to the 25.3% chance of an unexpected finding that may alter management or contra-indicate surgery.

-

3.

EGD should be routinely considered in populations where the community incidence of significant gastric and esophageal pathology is high, particularly when the procedure will lead to part of the stomach being inaccessible (for example RYGB and OAGB).

-

4.

EGD should be undertaken routinely for all patients after bariatric surgery at 1 year and then every 2–3 years for patients who have undergone LSG or OAGB to enable early detection of Barrett’s esophagus or upper GI malignancy until more data is available to confirm the incidence of these cancers in practice.

-

5.

EGD should be performed following AGB and RYGB on the basis of upper GI symptoms.

References

Fouse T, Brethauer S. Resolution of comorbidities and impact on longevity following bariatric and metabolic surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:717–32.

O’Brien PE, Hindle A, Brennan L, et al. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss at 10 or more years for all bariatric procedures and a single-centre review of 20-year outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):3–14.

Sjostrom L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. Jama. 2014;311:2297–304.

Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753–61.

Sjostrom L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56–65.

Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416–23.

Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish obese subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219–34.

Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. IFSO Worldwide Survey 2016: Primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):3783–3794.

Shaheen NJ, Weinberg DS, Denberg TD, et al. Upper endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:808–16.

Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988–1013.

Tolone S, Cristiano S, Savarino E, et al. Effects of omega-loop bypass on esophagogastric junction function. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:62–9.

Jammu GS, Sharma R. A 7-year clinical audit of 1107 cases comparing sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and mini-gastric bypass, to determine an effective and safe bariatric and metabolic procedure. Obes Surg. 2016;26:926–32.

Arman GA, Himpens J, Dhaenens J, et al. Long-term (11+years) outcomes in weight, patient satisfaction, comorbidities, and gastroesophageal reflux treatment after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1778–86.

Barr AC, Frelich MJ, Bosler ME, et al. GERD and acid reduction medication use following gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:410–5.

Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;319:255–65.

Chen RY, Burton PR, Ooi GJ, et al. The physiology and pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with laparoscopic adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2434–43.

Wolter S, Dupree A, Miro J, et al. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy prior to bariatric surgery-mandatory or expendable? An analysis of 801 cases. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1938–43.

Parikh M, Liu J, Vieira D, et al. Preoperative endoscopy prior to bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2961–6.

Sebastianelli L, Benois M, Vanbiervliet G, et al. Systematic endoscopy 5 years after sleeve gastrectomy results in a high rate of Barrett’s esophagus: results of a multicenter study. Obes Surg. 2019;29:1462–9.

Salama A, Saafan T, El Ansari W, et al. Is routine preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy screening necessary prior to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? Review of 1555 cases and comparison with current literature. Obes Surg. 2018;28:52–60.

Genco A, Soricelli E, Casella G, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a possible, underestimated long-term complication. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:568–74.

Felsenreich DM, Kefurt R, Schermann M, et al. Reflux, sleeve dilation, and Barrett’s esophagus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: long-term follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27:3092–101.

Braghetto I, Gonzalez P, Lovera C, et al. Duodenogastric biliary reflux assessed by scintigraphic scan in patients with reflux symptoms after sleeve gastrectomy: preliminary results. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(6):822–826.

Lee WJ, Almalki OM, Ser KH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity: comparison of the YOMEGA and Taiwan studies. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3047–53.

Hutopila I, Constantin A, Copaescu C. Gastroesophageal reflux before metabolic surgery. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2018;113:101–7.

Saarinen T, Kettunen U, Pietilainen KH, et al. Is preoperative gastroscopy necessary before sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:757–62.

Schneider R, Lazaridis I, Kraljevic M, et al. The impact of preoperative investigations on the management of bariatric patients; results of a cohort of more than 1200 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:693–9.

Heimgartner B, Herzig M, Borbely Y, et al. Symptoms, endoscopic findings and reflux monitoring results in candidates for bariatric surgery. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:750–6.

Fernandes SR, Meireles LC, Carrilho-Ribeiro L, et al. The role of routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2105–10.

Mora F, Cassinello N, Mora M, et al. Esophageal abnormalities in morbidly obese adult patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:622–8.

Carabotti M, Avallone M, Cereatti F, et al. Usefulness of upper gastrointestinal symptoms as a driver to prescribe gastroscopy in obese patients candidate to bariatric surgery. A prospective study. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1075–80.

Estevez-Fernandez S, Sanchez-Santos R, Marino-Padin E, et al. Esophagogastric pathology in morbid obese patient: preoperative diagnosis, influence in the selection of surgical technique. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:408–12.

Wiltberger G, Bucher JN, Schmelzle M, et al. Preoperative endoscopy and its impact on perioperative management in bariatric surgery. Dig Surg. 2015;32:238–42.

Petereit R, Jonaitis L, Kupcinskas L, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and eating behavior among morbidly obese patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Medicina (Kaunas). 2014;50:118–23.

Schigt A, Coblijn U, Lagarde S, et al. Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:411–7.

Tolone S, Limongelli P, del Genio G, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity: do we need to perform reflux testing in all candidates to bariatric surgery? Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S173–7.

D’Hondt MD, Steverlynck M, Elewaut A, et al. Value of preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Acta Chir Belg. 2013;113:249–53.

Peromaa-Haavisto P, Victorzon M. Is routine preoperative upper GI endoscopy needed prior to gastric bypass? Obes Surg. 2013;23:736–9.

Pilone V, Di Micco R, Monda A, et al. Positive findings in preoperative testing prior to gastric banding- their real value. Minerva Chir. 2013;68:529–35.

Humphreys LM, Meredith H, Morgan J, et al. Detection of asymptomatic adenocarcinoma at endoscopy prior to gastric banding justifies routine endoscopy. Obes Surg. 2012;22:594–6.

Masci E, Viaggi P, Mangiavillano B, et al. No increase in prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus in a surgical series of obese patients referred for laparoscopic gastric banding. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:613–5.

Bueter M, Thalheimer A, le Roux CW, et al. Upper gastrointestinal investigations before gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1025–30.

Kuper MA, Kratt T, Kramer KM, et al. Effort, safety, and findings of routine preoperative endoscopic evaluation of morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1996–2001.

Merrouche M, Sabaté J-M, Jouet P, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders in morbidly obese patients before and after bariatric surgery..pdf. Obes Surg. 2007;17:894–900.

Azagury D, Dumonceau JM, Morel P, et al. Preoperative work-up in asymptomatic patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: is endoscopy mandatory? Obes Surg. 2006;16:1304–11.

Korenkov M, Sauerland S, Shah S, et al. Is routine preoperative upper endoscopy in gastric banding patients really necessary. Obes Surg. 2006;16:45–7.

Gutschow CA, Collet P, Prenzel K, et al. Long-term results and gastroesophageal reflux in a series of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:941–8.

de Jong JR, van Ramshorst B, Timmer R, et al. The influence of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding on gastroesophageal reflux. Obes Surg. 2004;14:399–406.

Suter M, Dorta G, Giusti V, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:959–66.

Frigg A, Peterli R, Zynamon A, et al. Radiologic and endoscopic evaluation for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: preoperative and follow-up. Obes Surg. 2001;11:594–9.

Kavanagh R, Smith J, Bashir U, Jones D, Avgenakis E, Nau P. Optimizing bariatric surgery outcomes: a novel preoperative protocol in a bariatric population with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(4):1812–1818.

Sun WYL, Dang JT, Switzer NJ, et al. The utility of routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy before laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1717–22.

Gomez V, Bhalla R, Heckman MG, et al. Routine screening endoscopy before bariatric surgery: is it necessary? Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care. 2014;9:143–9.

Dutta SK, Arora M, Kireet A, et al. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and associated disorders in morbidly obese patients: a prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1243–6.

Loewen M, Giovanni J, Barba C. Screening endoscopy before bariatric surgery: a series of 448 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:709–12.

Mong C, Van Dam J, Morton J, et al. Preoperative endoscopic screening for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a low yield for anatomic findings. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1067–73.

Vanek VW, Catania M, Triveri K, et al. Retrospective review of the preoperative biliary and gastrointestinal evaluation for gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:17–22. discussioon −3

Zeni TM, Frantzides CT, Mahr C, et al. Value of preoperative upper endoscopy in patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:142–6.

Madan AK, Speck KE, Hiler ML. Routine preoperative upper endoscopy for laparoscopic gastric bypass- is it necessary. Am Surg. 2004;70:684–6.

Sharaf RN, Weinshel EH, Bini EJ, et al. Endoscopy plays an important preoperative role in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1367–72.

Schirmer B, Erenoglu C, Miller A. Flexible endoscopy in the management of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12:634–8.

Mazzini GS, Madalosso CA, Campos GM, et al. Factors associated to abnormal distal esophageal exposure to acid and esophagitis in individuals seeking bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15:710–6.

Viscido G, Gorodner V, Signorini F, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: endoscopic findings and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms at 18-month follow up. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:71–7.

Schlottmann F, Sadava E, Reino R, et al. Preoperative endoscopy in bariatric patients may change surgical strategy. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2017;47:117–21.

Czeczko LE, Cruz MA, Klostermann FC, et al. Correlation between pre and postoperative upper digestive endoscopy in patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal bypass. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29:33–7.

Assef MS, Melo TT, Araki O, et al. Evaluation of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28(Suppl 1):39–42.

Dietz J, Ulbrich-Kulcynski JM, Souto KEP, et al. Prevalence of upper digestive endoscopy and gastric histopathology findings in morbidly obese patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:52–5.

Munoz R, Ibanez L, Salinas J, et al. Importance of routine preoperative upper GI endoscopy: why all patients should be evaluated? Obes Surg. 2009;19:427–31.

de Moura AA, Cotrim HP, Santos AS, et al. Preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: is it necessary? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:144–9. discussion 50-1

Teivelis MP, Faintuch J, Ishida R, et al. Endoscopic and ultrasonographic evaluation before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:8–13.

Abd Ellatif ME, Alfalah H, Asker WA, et al. Place of upper endoscopy before and after bariatric surgery: a multicenter experience with 3219 patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:409–17.

Yardimci E, Bozkurt S, Baskoy L, et al. Rare entities of histopathological findings in 755 sleeve gastrectomy cases: a synopsis of preoperative endoscopy findings and histological evaluation of the specimen. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1289–95.

Mihmanli M, Yazici P, Isil G, et al. Should we perform preoperative endoscopy routinely in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery? Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care. 2016;11:73–7.

Baysal B, Kayar Y, Danalioglu A, et al. The importance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in morbidly obese patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:228–31.

Abou Hussein B, Khammas A, Shokr M, et al. Role of routine upper endoscopy before bariatric surgery in the Middle East population: a review of 1278 patients. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1171–e6.

D’Silva M, Bhasker AG, Kantharia NS, et al. High-percentage pathological findings in obese patients suggest that esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy should be made mandatory prior to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28:2753–9.

Praveenraj P, Gomes RM, Kumar S, et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical implications of preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:465–9.

Sharma A, Aggarwal S, Ahuja V, et al. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux before and after sleeve gastrectomy using symptom scoring, scintigraphy, and endoscopy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:600–5.

Al Akwaa AM, Alsalman A. Benefit of preoperative flexible endoscopy for patients undergoing weight-reduction surgery in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:12–4.

Ng JY, Cheng AKS, Kim G, et al. Is elective gastroscopy prior to bariatric surgery in an Asian cohort worthwhile? Obes Surg. 2016;26:2156–60.

Lee J, Wong SK, Liu SY, et al. Is preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery mandatory? An Asian perspective. Obes Surg. 2017;27:44–50.

Wong HM, Yang W, Yang J, et al. The value of routine gastroscopy before laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in Chinese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:303–7.

Tai CM, Huang CK, Lee YC, et al. Increase in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and erosive esophagitis 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy among obese adults. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1260–6.

Korenkov M, Sauerland S, Shah S, et al. Is routine preoperative upper endoscopy in gastric banding patients really necessary? Obes Surg. 2006;16:45–7.

Schigt A, Coblijn U, Lagarde S, et al. Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:411–7. quiz 565-6

Schirmer B, Erenoglu C, Miller A. Flexible endoscopy in the management of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12:634–8.

Wang Q-L, Xie S-H, Wahlin K, et al. Global time trends in the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:717–28.

Kim Y, Park J, Nam B-H, et al. Stomach cancer incidence rates among Americans, Asian Americans and Native Asians from 1988 to 2011. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015006–e.

Whiteman DC, Kendall BJ. Barrett’s oesophagus: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Med J Aust. 2016;205:317–24.

Aggarwal S, Bhambri A, Singla V, Dash NR, Sharma A. Adenocarcinoma of oesophagus involving gastro-oesophageal junction following mini-gastric bypass/one anastomosis gastric bypass. J Minim Access Surg. 2019;16(2):175–178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

No ethical review is required for this activity.

Conflict of Interest

Wendy A. Brown reports grants from Johnson and Johnson, grants from Medtronic, grants from GORE, personal fees from GORE, grants from Applied Medical, grants from Apollo Endosurgery, grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisc, and personal fees from Merck Sharpe and Dohme, outside the submitted work, and I am a bariatric surgeon so I earn my living from performing these procedures. Scott Shikora reports that he is the editor-in-chief for Obesity Surgery. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The IFSO appointed task force reviewing the literature on Endoscopy in Bariatric Surgery

Appendices

Appendix 1. Members of the IFSO appointed task force reviewing the literature on Endoscopy in Bariatric Surgery

Kelvin Higa—USA

Scott Shikora—USA

Guilherme M. Campos—USA

Yazmin Johari Halim Shah—Australia

George Balalis—Australia

Wendy Brown—Australia

Lilian Kow—Australia

Jacques Himpens—Belgium

Almino Ramos—Brazil

Miguel Herrera—Mexico

Ahmad Bashir—Jordan

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, W.A., Johari Halim Shah, Y., Balalis, G. et al. IFSO Position Statement on the Role of Esophago-Gastro-Duodenal Endoscopy Prior to and after Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Procedures. OBES SURG 30, 3135–3153 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04720-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04720-z