Abstract

Background

The impact of bariatric surgery (BS) on the sexual functioning of patients is poorly studied. Our aim was to analyze the sexual function, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem of morbidly obese women (MOW) undergoing BS.

Patients and Methods

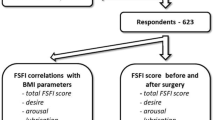

Quality of sexual life was prospectively evaluated in 43 consecutive MOW (18–50 years) who underwent BS. Female sexual function index (FSFI), Beck depression inventory (BDI), and Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) questionnaires were administered to evaluate sexual satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem, respectively. A control group of 36 healthy, non-obese, female patients (HW) was recruited for comparison. Results of questionnaires were compared between three periods (before BS and at 3- and 6-month follow-up) and between MOW and HW.

Results

Before BS, the FSFI score was significantly lower in MOW compared to HW (17 ± 12 vs 27 ± 8, p = 0.0001) while at 3- and 6-month post-BS, a significant amelioration (p = 0.01) occurred. In particular, after BS, all components of the FSFI score (sexual desire, excitement, lubrification, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) were ameliorated. The pre-BS BDI score was higher in MOW than in HW (8 ± 6 vs 5 ± 5, p = 0.004) while at postoperative months 3 and 6, a significant amelioration was found (p = 0.025 and 0.005, respectively). Before BS, no significant differences occurred in the RSES score between MOW and HW (30 ± 7 vs 32 ± 6, p = 0.014), whereas the MOW RSES scores at 6-month post-BS were improved when compared with the HW RSES scores.

Conclusions

BS results in a significant improvement in the quality of sexual life, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem in MOW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity represents a major health problem worldwide. The World Health Organization estimated the presence of approximately 700 million obese adults in 2015, with rising trends of obesity in most countries [1, 2]. In France, the prevalence of obesity was estimated at 15% in 2012 [3]. Obesity is associated with the development of several diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipemia, coronary artery disease, obstructive apnea syndrome, and several cancers including breast, uterus, prostate, and liver cancers [4]. Furthermore, obesity is associated with depression [5] and has a negative impact on the patients’ quality of life [6]. There is evidence that obesity can affect the sexual response in both men and women [7]. In women, sexual dysfunction is a multicausal and multidimensional problem including biological, psychological, and interpersonal factors leading to persistent, recurrent problems with sexual response, desire, orgasm, or pain that distress the woman and/or strain the relationship with her partner [8].

Bariatric surgery (BS) represents an effective treatment option for morbid obesity, and its volume is exponentially rising worldwide [9, 10]. BS has been proven to be effective in improving long-term survival and controlling obesity-related comorbidities [11]. Whereas the effect of BS on metabolic diseases has been widely studied, less is known about its role on the sexual health and functioning of patients. While there is evidence that BS has a positive effect on quality of life and depressive symptoms [12], the effect of BS on sexual health and functioning is still debated. Some studies have found that BS has a positive effect possibly related to the satisfaction of improvement in body image [13, 14]. Other authors, however, did not find significant differences in the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction before and after BS [15]. The aim of this prospective longitudinal study was to analyze the sexual function, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem of morbidly obese women (MOW) undergoing BS compared to a control population of healthy non-obese women (HW).

Patients and Methods

A prospective longitudinal study to evaluate the quality of sexual life of MOW undergoing BS was designed. Indications for BS were consistent with Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) recommendations [16] which mirror those of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders. Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) were performed, after multidisciplinary evaluation by the bariatric team. All MOW, aged between 18 and 50 years, undergoing BS between October and November 2015 were considered for inclusion in the present study, if they were able to understand the French version of the administered questionnaires and if they did not have documented psychiatric diseases. Only patients undergoing primary bariatric procedures were included, whereas patients undergoing revisional surgery were not taken into account to avoid the potential confounding effect of weight recidivism and failure of the first bariatric procedure on patients’ perception of the potential changes observed after the loss of weight. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Department of Research of the Faculty of Medicine (Université Côte d’Azur- Nice, France), and data were retrieved from a prospective database on BS (CNIL number 6009701).

A single author administered the three questionnaires on sexual life, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms to 43 consecutive MOW within 1 month before the day of surgery, and at 3 and 6 months after surgery. The female sexual function index (FSFI) questionnaire was administered to evaluate sexual satisfaction [17, 18]. The Beck depression inventory (BDI) and Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) were used to evaluate depressive symptoms and self-esteem, respectively [19, 20].

A control group of HW between 18 and 50 years of age was recruited for comparison by the same author. Patients included in the control group had no diabetes, blood hypertension, arthritis, hyperlipidemia, thyroid diseases, autoimmune diseases, and psychiatric disorders. The same author administered the questionnaires by email to women in the HW group.

The results of the questionnaires were compared between the three periods (before BS and at 3 and 6 months) and between the study (MOW) and the control group (HW).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were reported as mean ± standard deviation, whereas qualitative data were reported as a percentage. Quantitative data were compared using the Mann–Whitney test, whereas the chi-square test was used for qualitative data. NCSS 2007 (Kaysville, UT) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Thirty-six MOW and 46 HW were included in the present study (Fig. 1). Demographic characteristics of MOW and HW are listed in Table 1. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the two groups in terms of body mass index (BMI), use of contraception, and professional activity. The scores of FSFI and BDI were significantly different between MOW and HW (17 ± 12 vs 27 ± 8, p < 0.05; 8 ± 6 vs 5 ± 5, p < 0.05, respectively), indicating better sexual quality of life and lower depression score in HW, whereas no differences (30 ± 7 vs 32 ± 6, p > 0.05) were found with the Rosenberg questionnaire (Table 2). Professional status, marital status, and contraception had no significant influence on the scores of the tests.

Results of the FSFI Test After Surgery

As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2, before BS, the FSFI score was significantly lower in MOW compared to that in HW (17 ± 12 vs 27 ± 8, p = 0.0001) while at post-BS months 3 and 6, a significant amelioration (p = 0.01) was found. Indeed, there was no significant difference between HW and MOW at 6 months (Fig. 2). In particular, as reported in Fig. 3, after BS, all components of the FSFI score such as sexual desire (Fig. 3a), excitement (Fig. 3b), lubrification (Fig. 3c), orgasm (Fig. 3d), satisfaction (Fig. 3e), and pain (Fig. 3f) were ameliorated.

Results of the BDI Score and RSES Score After Surgery

As reported in Table 2 and Fig. 2, pre-BS BDI score was higher in MOW than in HW (8 ± 6 vs 5 ± 5, p = 0.004) while at postoperative months 3 and 6, a significant amelioration was found (p = 0.025 and 0.005, respectively). Indeed, there was no significant difference between HW and MOW at 6 months.

Before BS, no significant differences were found for RSES score between MOW and HW (30 ± 7 vs 32 ± 6, p = 0.014), whereas MOW RSES scores at post-BS month 6 was improved when compared with the HW RSES scores (Figs.4 and 5). Evolution of the results of the three tests in the study group is reported in Table 3.

Correlation Between FSFI Score, Beck Score, and Rosenberg Score After Surgery

In HW, a significant correlation between sexual quality of life and self-esteem was found, with high self-esteem related to a better quality of sexual life (R2 1.109; correlation 0.333; p = 0.0237) and depression score was inversely correlated to self-esteem (R2 0.5536; correlation − 0.7441; p < 0.00001), as expected. On the other hand, in MOW, at preoperative evaluation, no significant correlation between self-esteem and quality of sexual life was found (R2 0.0725; correlation 0.2692; p = 0.1124), whereas Beck score was inversely correlated to self-esteem (R2 0.3852; correlation − 0.6207; p = 0.0001), indicating that patients with high self-esteem were significantly less prone to depression.

Three months after surgery, a significant correlation between sexual quality of life and self-esteem emerged (R2 0.3837 correlation 0.6195; p = 0.0016), whereas no correlation between sexual life and depression scale was found (R2 0.1440 correlation − 0.3795 p = 0.0741). At 6 months, the correlation between sexual quality of life and self-esteem was still significant (R2 0.3134; correlation 0.5598; p = 0.0103) and a correlation between sexual quality of life and depression score emerged (R2 0.3129; correlation − 0.5594; p = 0.0103). The correlation between self-esteem and depression score was still significant (R2 0.6804; correlation − 0.8249; p = 0.00001).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that BS is followed by a significant improvement in the quality of sexual life, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem in MOW.

Several authors have advocated an improvement in the quality of sexual life after BS. Camps et al. have demonstrated the amelioration of sexual life, orgasms, and corporeal image 1 year after surgery in a group of 28 patients [21]. Kinzl et al. [22] showed amelioration of sexual life in 63% of patients in a study on 82 patients who underwent BS. Other studies focusing on quality of life have pointed out the amelioration of sexual life after BS [23, 24]. However, these studies did not use specific questionnaires for female sexuality. Bond et al. [25, 26] administered the FSFI questionnaire in their studies, but the comparison between preoperative and postoperative results was done on different groups of patients. Assimakopoulos et al. [27, 28] are the only authors reporting a prospective study evaluating FSFI scores, hospital anxiety, and depression scale.

Our results indicate that the MOW have a low quality of sexual life, moderate presence of depressive symptoms, and that the latter are correlated with self-esteem. In comparison with the HW, the MOW had similar marital status but lower contraceptive use (38.9% versus 63%), which is consistent with the French study on sexuality by Bajos et al. [29]. Professional status was also significantly different between the two groups because in the control group, subjects were more active. However, this result may be explained by a selection bias of the control group. Quality of sexual life was lower in MOW and depressive symptoms were more frequent than in controls. Patients waiting for BS had a deterioration in the quality of sexual life affecting all aspects, with a mean FSFI score of 17. In a study by Bond et al. [26], preoperative FSFI score was better, as high as 24.6; however, only patients with declared sexual relationships during the previous months were included in this study. Assimakopoulos et al. [28] found similar results for 60 patients waiting for BS, with a mean FSFI score of 21.3.

Six months after BS, we found a significant improvement in self-esteem, quality of sexual life and lower depression scores. The correlation between self-esteem and depression, detected preoperatively, was also present at 3 and 6 months. These data are consistent with the majority of previous findings. Bond et al. [25] and Assimakopoulos et al. [27] demonstrated significant amelioration of FSFI scores in two studies on 54 and 59 patients, respectively.

However, Janik et al. [15] failed to demonstrate a significant amelioration in the quality of sexual life at 12 and 18 months after surgery. The authors included 21 patients in the preoperative group and 28 in the postoperative group. The main bias of this work relies on the fact that the patients in the two groups were not the same, which may account for the lack of positive results.

Concerning depression, we found a moderate depression score in the MOW group. This score was higher than in the control subjects and was ameliorated at 3 and 6 months after surgery. These results are concordant with those reported by Dymek et al. [30] on a group of male and female patients before and after BS. Regarding self-esteem, we did not find significant differences between patients and controls. At 6-month follow-up, a significant improvement was noted in the self-esteem of the patients, in accordance with the study by Dymek et al. [30].

There is no published study analyzing the correlation between the quality of sexual life, self-esteem, and depression in a longitudinal way. Our results suggest that these three dimensions are linked.

The main strengths of the present study are the use of the FSFI questionnaire, which is the only validated tool for the evaluation of the quality of sexual life in women and the prospective, longitudinal design of the study as well as the presence of a control group of non-obese, healthy women. The main limitation of the present study is the small number of patients included and the limited follow-up. Indeed, it may be argued that other factors may impact the evolution of sexual response with time such as weight regain and changes in body image due to massive weight loss [14]. This study also lacks a power analysis. However, although this may be seen as a limitation, it should be argued that only few studies have been published with the use of these scores in the setting of BS and none includes the three questionnaires. This study should then be interpreted as a pilot study investigating the effect of BS on the sexual function of MOW that is explored not only through the specific FSFI questionnaire on quality of sexual life but also through the analysis of the self-esteem and depression. Indeed, the latter proved to be correlated to sexual quality of life. These results should be confirmed in a long-term longitudinal study including a large cohort of patients designed to assess the effectiveness of BS on the quality of sexual life in MOW.

Conclusion

The present study shows that MOW waiting for BS have a lower quality of sexual life and higher depression scores than HW and that BS significantly improves the quality of sexual life and self-esteem, and diminishes depressive symptoms at 6-month follow-up. BS not only results in medical and quality of life benefits but also provides women with a significant improvement in sexual function.

References

Arroyo-Johnson C, Mincey KD. Obesity epidemiology worldwide. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2016;45:571–9.

Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2010;39(1):1–7.

OBEPI-Roche 2012. Enquête nationale sur l’obésité et le surpoids. http://www.roche.fr/innovation-recherche-medicale/decouverte-scientifique-medicale/cardio-metabolisme/enquete-nationale-obepi-2012.html. Accessed 30 April 2017.

Park J, Morley TS, Kim M, et al. Obesity and cancer--mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(8):455–65.

Preiss K, Brennan L, Clarke D. A systematic review of variables associated with the relationship between obesity and depression. Obes Rev. 2013;14(11):906–18.

Taylor VH, Forhan M, Vigod SN, et al. The impact of obesity on quality of life. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(2):139–46.

Rowland DL, McNabney SM, Mann AR. Sexual function, obesity, and weight loss in men and women. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(3):323–38.

Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888–93.

Debs T, Petrucciani N, Kassir R, et al. Trends of bariatric surgery in France during the last 10 years: analysis of 267,466 procedures from 2005-2014. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(8):1602–9.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO worldwide survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2279–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2666-x.

Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12012. Review

Strain GW, Kolotkin RL, Dakin GF, et al. The effects of weight loss after bariatric surgery on health-related quality of life and depression. Nutr Diabetes. 2014;4:e132. https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.29.

Sarwer DB, Spitzer JC, Wadden TA, et al. Changes in sexual functioning and sex hormone levels in women following bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(1):26–33.

Conason A, McClure Brenchley KJ, Pratt A, et al. Sexual life after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):855–61.

Janik MR, Bielecka I, Paśnik K, et al. Female sexual function before and after bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study and review of literature. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1511–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1721-8.

HAS clinical practice guidelines. Obesity surgery in adults. https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2010-11/obesity-surgery-guidelines.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2017

Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005 Jan-Feb;31(1):1–20.

Female Sexual Function Index Website, http://www.fsfiquestionnaire.com, Accessed 1 May 2017

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Vallieres EF, Vallerand RJ. Traduction et validation Canadienne-Française de l’Echelle de l’Estime de soi de Rosenberg. Int J Psychol. 1990;25:305–16.

Camps MA, Zervos E, Goode S, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on body image perception and sexuality in morbidly obese patients and their partners. Obes Surg. 1996;6(4):356–60.

Kinzl JF, Schrattenecker M, Traweger C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16(12):1609–14.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Gress RE, et al. Two-year changes in health-related quality of life in gastric bypass patients compared with severely obese controls. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(2):250–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2009.01.009.

Dziurowicz-Kozłowska A, Lisik W, Wierzbicki Z, et al. Health-related quality of life after the surgical treatment of obesity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 6):127–34.

Bond DS, Wing RR, Vithiananthan S, et al. Significant resolution of female sexual dysfunction after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(1):1–7.

Bond DS, Vithiananthan S, Leahey TM, et al. Prevalence and degree of sexual dysfunction in a sample of women seeking bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(6):698–704.

Assimakopoulos K, Karaivazoglou K, Panayiotopoulos S, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with reduced depressive symptoms and better sexual function in obese female patients: a one-year follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2011;21(3):362–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0303-z.

Assimakopoulos K, Panayiotopoulos S, Iconomou G, et al. Assessing sexual function in obese women preparing for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16(8):1087–91.

Bajos N, Bozon M, Godelier M. Enquete sur la sexualite en France. Paris: La Decouverte; 2008.

Dymek MP, Le Grange D, Neven K, et al. Quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a cross-sectional study. Obes Res. 2002;10(11):1135–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained for each individual participant included in the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cherick, F., Te, V., Anty, R. et al. Bariatric Surgery Significantly Improves the Quality of Sexual Life and Self-esteem in Morbidly Obese Women. OBES SURG 29, 1576–1582 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03733-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03733-7