Abstract

Background

Patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for the resolution of morbid obesity have significant medical sequelae related to their weight. One of the most common comorbid conditions is joint pain requiring the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). In addition to NSAIDs, patients may engage in behaviors such as smoking and alcohol misuse that increase the risk of long-term postoperative complications to include gastric perforation.

Methods

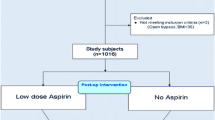

Data on 1,690 patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery were collected prospectively and reviewed retrospectively.

Results

We identified seven patients who presented to an emergency room and subsequently required emergent surgical intervention for repair of gastric perforation. Six of the seven cases involved use or abuse of NSAIDs.

Conclusion

Important characteristics were identified including the use of NSAIDs, alcohol use, and non-compliance with routine long-term postoperative follow-up. Identifying those patients at high risk may decrease the incidence of this potentially life-threatening complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) has emerged as the most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedure in the USA. The number of patients undergoing RYGB surgery is expected to exceed 150,000 cases in 2007. Numerous studies outline the efficacy of bariatric surgery and the dramatic health improvements and gains in longevity that patients experience after undergoing RYGB surgery [1].

However, recent findings indicate that marginal ulcer (MU) can occur after RYGB [2]. MU is defined as a gastric ulcer of the jejunal mucosa near the site of a gastrojejunostomy [2]. Proposed theories of MU etiology include ischemia, foreign body reactions, fistula, acid production, inflammation, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) [3–7]. As with any gastrointestinal anastomosis, incidence of MU is expected to be in the range of 1.8–3.1% [8] Sacks et al. [9] in 2006 conclude that the use of non-absorbable suture material increases incidence of MU. Gastric ulcer perforation in patients who have undergone RYGB surgery can occur in two separate and distinct anatomic places:

-

1.

The stomach remnant, which includes the antral-duodenal region as well as the large stomach body. Evidence exists that the bypassed gastric segment continues to have gastric secreting capabilities. Bjorkman et al. [8] in 1989 contributed an interesting case study demonstrating acid-related gastroduodenal disease in a bypassed gastrointestinal tract. Access and evaluation of the bypassed stomach is challenging and can delay treatment [10, 11].

-

2.

The small stomach pouch and the gastrojejunal region, which would include MU. It has been suggested that the smaller pouch would reduce acid exposure at the anastomosis and adjacent jejunum [4] (Table 1).

There are many variables to consider in the prevention of MU. The extent to which risk factors of MU are sought, identified, avoided, or mitigated varies with each provider. Currently, there is not uniform consensus on prophylaxis against development of ulcer disease. Recent studies, however, indicate that empiric proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy in the first 8 weeks after RYGB may decrease the incidence of MU development [4]. Gumbs et al. [12] in 2006 reported on 16 documented cases of MU after RYGB. It is felt by these investigators that MU is underreported and can successfully be treated with short-term use of PPI therapy.

There are no studies to date which confirm a relationship between H. pylori, gastric bypass, and MU formation. However, a correlation has been suggested by several studies [13]. Madan et al. [14] in 2004 documented a 20% incidence of H. pylori preoperatively among patients undergoing gastric bypass. Schirmer et al. [7] in 2002 investigated 206 patients preoperatively. The results on endoscopic exam identified and treated 62 patients positive for H. pylori and decreased the MU rate from 6.8 to 2.4% in this group. Further studies would be of value to determine standards of care with regard to H. pylori and MU prevention.

Materials and Methods (Case Presentations)

Prospective data are collected on all patients undergoing RYGB surgery. Records of 1,690 patients were reviewed to identify the seven cases presented herein. In each case, the abdomen was thoroughly irrigated at time of surgical repair and a drain placed. No cases of gastro-gastric fistula have been identified in the series. The incidence of gastric ulcer perforation in this series is 0.4%, with average length of time to perforation 32.6 months (Tables 2 and 3).

Case number 1 is a 58-year-old female who underwent laparoscopic retrocolic RYGB surgery in Los Angeles in 2002, approximately 3 1/2 years before presentation at our institution. Although she had experienced resolution of many comorbid conditions, she continued to have severe degenerative joint disease and pain in her spine, hips, and weight-bearing joints. She was receiving monthly corticosteroid injections for the spine and joint disease. She was intermittently taking Prilosec, a proton pump inhibitor, but was non-compliant with daily treatment. On rare occasions, the patient took aspirin orally. She denied the use of alcohol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). This patient developed severe epigastric pain with radiation to the shoulders and back. She presented to the emergency room where she was found to have pneumoperitoneum. She was taken urgently to surgery and was found to have free fluid in the abdomen and a perforation on the anterior aspect of the gastrojejunal anastomosis at the site of a marginal ulcer. The perforation was treated with an oversewing technique and omental patch. She recovered after a 6-day hospital course and was discharged home in stable condition. Discharge medications include: Carafate slurry, 1 g p.o. four times daily and Prilosec, 20 mg p.o. twice daily.

Case number 2 is a 55-year-old female with a history of morbid obesity, diabetes mellitus, degenerative joint disease. She underwent laparoscopic retrocolic RYGB in 2002. Postoperatively, she used NSAIDs extensively for treatment of her degenerative spine and joint pain. She presented to the emergency room in 2003 with an acute abdomen. Abdominal films demonstrated pneumoperitoneum. With surgical exploration, she was found to have a perforation of a prepyloric gastric ulcer. This was treated with oversewing and omental patch. After a difficult hospital course, she recovered to her previous level of functioning. She improved and did well for approximately 2 years until she needed spinal surgery. She later developed complications including osteomyelitis of the thoracic spine. After multiple hospitalizations, she died in 2005 from recurrent sepsis unrelated to abdominal surgery or peptic ulcer disease.

Case number 3 is a 27-year-old female with a history of mild depression, morbid obesity, chronic back pain, headaches, and irregular menses. She had a successful laparoscopic retrocolic RYGB in 2003. After the death of a sibling, she was diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. In 2005, she began abusing alcohol and also started smoking. Resulting chronic abdominal pain was self-treated with NSAIDs, taking “handfuls” of ibuprofen on a daily basis. She presented to a local emergency room with severe abdominal pain where was found to have peritoneal signs and pneumoperitoneum. Upon exploration, she was found to have a perforated marginal ulcer at the gastrojejunal anastomosis. This was treated with oversewing and omental patch. This patient was referred for alcohol dependency treatment and was advised about absolute contraindication of NSAIDs and alcohol. She recovered uneventfully.

Case number 4 is a 22-year-old female who had a history of asthma, chronic back pain, and morbid obesity. She underwent a laparoscopic antecolic RYGB procedure in 2003. She began experiencing headaches in late 2005 and was taking 800 to 1,000 mg of ibuprofen every 6 h. She presented to the emergency room with a 6-h history of increasing abdominal pain and she was found to have pneumoperitoneum. She was taken to surgery and the abdomen was explored with an open laparotomy. She was found to have a perforated ulcer at the gastrojejunal anastomosis. This was treated with oversewing and omental patch. She recovered rapidly with no long-term effects.

Case number 5 is a 46-year-old female with history of morbid obesity and medical sequelae of hypertension and degenerative joint disease. She underwent a successful retrocolic RYGB in 2002. She used NSAIDs for management of persistent bone and joint pain. She presented in 2004 with abdominal pain and was found to have pneumoperitoneum. Upon exploration, she was found to have a perforated ulcer at the gastrojejunal anastomotic region. She was surgically treated with oversewing and omental patch. Two weeks postoperatively, she was admitted with a small bowel obstruction and an internal hernia. A Baker tube was placed at this time. After a brief hospital stay, she was discharged home and maintained on proton pump inhibitor therapy. She has not complained of any further or residual complications.

Case number 6 is a 52-year-old female with history of morbid obesity and medical sequelae of hypertension and degenerative joint disease. She underwent a successful retrocolic laparoscopic RYGB in 2002. Postoperatively, she used NSAIDs for treatment of bone and joint pain. She presented in 2005 with abdominal pain and was found to have pneumoperitoneum. Upon exploration, she was found to have a perforated ulcer at the gastrojejunal anastomotic region. She was treated with oversewing and omental patch. After repair, the patient recovered and was discharged home with instructions for long-term care. Discharge management included Carafate and PPI therapy.

Case number 7 is a 47-year-old male with history of morbid obesity and medical sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea and degenerative joint disease. He underwent a laparoscopic antecolic RYGB in 2002. He lost in excess of 120 lbs and reported a remarkable improvement in his quality of life and health. However, NSAIDs were used for control of spine and joint pain. He presented in 2006 to a small hospital in another state with abdominal and chest pain. Despite reporting previous gastric bypass surgery and repeated documentation of this history, he was treated with Toradol and corticosteroids and then sent home. He returned to the same emergency department the following day in extremis. Upon exploration, he was found to have a perforated gastric ulcer and died of multiorgan failure (Table 4).

Discussion

This report describes seven cases of gastric ulcer perforation in patients who had previously undergone RYGB surgery. These cases represent all those identified in a review of 7,200 patient-years of follow-up in gastric bypass patients at our center. An incidence of 0.4% with 36 months of follow-up is reported. Authors have postulated that larger pouch size, antecolic position, or other anatomic factors increase risk of marginal ulceration [4, 15–18]. Most of our cases have occurred in patients with retrocolic position. Many studies document a positive correlation with the use of irrigation and the placement of drains and resolution of abscess [8, 11, 13]. Some studies have shown an association between gastro-gastric fistula and marginal ulcer [2, 4, 18]. However, this was not evident in the seven cases presented. Pouch size is small but difficult to quantify in this series. Six of the seven cases involved use or abuse of NSAIDs; one case involved alcohol abuse. A particularly troubling case involved a patient who presented twice to an outside hospital where care rendered was provided by health professionals unfamiliar with the complexities of long-term management of gastric bypass.

Gastric ulcer perforation is a serious and relatively frequent event among patients who have undergone RYGB. Identification of risk factors in all these patients suggests that this problem may be preventable with improved patient education. H. pylori presence is not routinely screened preoperatively at most centers, although an increasing number of centers are beginning to do so. Efficacy and safety of eradication of H. pylori in treatment of perforated ulcers is still being examined [19]. Each of the patients discussed in previous case studies was treated empirically against H. pylori after development of ulcer perforation. To our knowledge, at time of submission, none has recurred. Rabeprazole has been noted to be as effective as omeprozole and lansoprazole as part of a triple therapy regimen to treat H. pylori [20]. Selection of PPI at our institution has recently become limited by patient formulary.

What lessons can be learned? MU complication requires increased knowledge and awareness. Long-term patient follow-up appears important in tracking outcomes as well as promoting patient education. Patients who resume care with a health care provider unfamiliar with bariatric medicine may put themselves at increased risk of being prescribed NSAIDs and corticosteroids. These medications appear to increase the risk of ulcer formation and perforation. We believe that the incidence of MU may be reduced with H. pylori investigation, empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy, as well as avoidance of NSAIDs. Our practice has focused on the latter two and in the future will incorporate H. pylori testing and treatment preoperatively. Beginning in 2004, patients were treated with empiric proton pump inhibitors postoperatively. Before 2004, patients were treated with PPI therapy on a case-by-case basis. At this time, no cases have occurred since adopting a two-phased approach to ulcer prevention:

-

1.

Empiric 12-week treatment with proton pump inhibitors immediately after surgery and

-

2.

Zero-tolerance policy toward NSAIDs in gastric bypass patients.

Future studies will need to guide us with respect to H. pylori and anatomic factors which may or may not affect the incidence of this serious problem.

References

Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007 Aug;357:753–61.

Sapala JA, Wood MH, Sapala MA, et al. Marginal ulcer after gastric bypass: a prospective 3-year study of 173 patients. Obes Surg. 1998;8:505–16.

Dallal RM, Bailey LA. Ulcer disease after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:455–9.

Hedberg J, Hedenstrom H, Nilsson S, et al. Role of gastric acid in stomal ulcer after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1375–8.

Pope GD, Goodney PP, Burchard KW, et al. Peptic ulcer/stricture after gastric bypass: a comparison of technique and acid suppression variables. Obes Surg. 2002;12:30–3.

Ramaswamy A, Lin E, Ramshaw BJ, et al. Early effects of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1094–6.

Schirmer B, Erenoglu C, Miller A. Flexible endoscopy in the management of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12:634–8.

Bjorkman DJ, Alexander JR, Simons MA. Perforated duodenal ulcer after gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:170–2.

Sacks BC, Mattar SG, Qureshi FG, et al. Incidence of marginal ulcers and the use of absorbable anastomotic sutures in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:11–6.

Papasavas PK, Yeaney WW, Caushaj PF, et al. Perforation in the bypassed stomach following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:797–9.

Macgregor AM, Pickens NE, Thoburn EK. Perforated peptic ulcer following gastric bypass for obesity. Am Surg. 1999;65:222–5.

Gumbs AA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Incidence and management of marginal ulceration after laparoscopic Roux-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:460–3.

Lublin M, McCoy M, Waldrep DJ. Perforating marginal ulcers after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:51–4.

Madan AK, Speck KE, Hiler ML. Routine preoperative upper endoscopy for laparoscopic gastric bypass: is it necessary? Am Surg. 2004;70:684–6.

Mason EE, Munns JR, Kealey GP, et al. Effect of gastric bypass on gastric secretion. Am J Surg. 1976;131:162–8.

Jordan JH, Hocking MP, Rout WR, et al. Marginal ulcer following gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Am Surg. 1991;57:286–8.

Smith CD, Herkes SB, Behrns KE, et al. Gastric acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption after vertical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1993;218:91–6.

MacLean LD, Rhode BM, Nohr C, et al. Stomal ulcer after gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:1–7.

Rodriguez-Sanjuan JC, Fernandez-Santiago R, Garcia RA, et al. Perforated peptic ulcer treated by simple closure and Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Surg. 2005;29:849–52.

Kumar R, Tandon VR, Bano G, et al. Comparative study of proton pump inhibitors for triple therapy in H. pylori eradication. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:100–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sasse, K.C., Ganser, J., Kozar, M. et al. Seven Cases of Gastric Perforation in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Patients: What Lessons Can We Learn?. OBES SURG 18, 530–534 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9335-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9335-4