Abstract

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) after bariatric surgery is well documented. Although infrequent, it can be associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. The laparoscopic approach to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) has gained widespread popularity for the treatment of morbid obesity since its first description in 1994. One of the theoretical advantages of a minimally invasive technique is reduced intraabdominal adhesions and, consequently, diminution in the incidence of SBO. However, the laparoscopic approach demonstrates a similar rate of obstruction to the open procedure. In this review, an electronic literature search was undertaken of Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases for the period January 1990 to October 2006 on the history, presentation, clinical evaluation, preoperative diagnostic techniques, and management of SBO after LRYGB compared to the open approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Morbid obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the US. Thirty percent of adults are obese and 15% are morbidly obese [1]. This problem is not only confined to the US, but is a major health problem worldwide. Bariatric surgery is the only successful treatment option for maintained long-term weight loss in the morbidly obese, and the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the most common procedure performed [1–3]. The laparoscopic approach to the RYGB has been increasing in popularity with demonstrated advantages over the traditional open technique in terms of fewer wound complications, better cosmesis, less postoperative pain, shorter length of hospital stay, faster recovery, and reduced incidence of incisional hernias [4–7]. However, complications including gastric outlet obstruction, anastomotic leaks, ulcers, and small bowel obstruction (SBO) are similar between the two techniques [8–11]. Some studies report a higher incidence of SBO after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) when compared to the open approach [3, 12, 13]. Also, there are notable differences in the etiology, presentation, and management of SBO after LRYGB [3, 9, 11, 14–16].

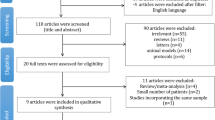

Therefore, an electronic literature search of the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases was undertaken for the period January 1990 to October 2006 on the history, presentation, clinical evaluation, preoperative diagnostic techniques, and management of SBO after LRYGB compared to the open approach. Simplified classification systems were then devised to describe SBO on the basis of the anatomic site of obstruction and timing of onset of symptoms after LRYGB.

Various Surgical Techniques

The first open RYGB for weight loss was performed by Mason and Ito in 1967, and it is now regarded as the gold standard procedure by most bariatric surgeons [2, 17, 18]. Wittgrove et al. introduced the laparoscopic approach in 1994 confirming its safety and feasibility as an alternative technique [19]. The RYGB is performed by creating a small volume gastric pouch and a Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy [20, 21]. A small 15–30 ml proximal gastric pouch based on the lesser curvature is fashioned with exclusion of the fundus and the remainder of the stomach. The jejunum is transected 45–50 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz creating the biliopancreatic limb. The transected distal jejunal loop or alimentary limb is anastomosed to the gastric pouch to create a narrow gastrojejunal anastomoses (GJA) or stoma. The biliopancreatic limb is then anastomosed to the alimentary limb ≥100 cm below the gastrojejunostomy to create a common channel. The majority of the stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum are excluded or ‘bypassed’. Weight loss occurs because of the reduction in gastric volume with restricted intake and early satiety, the dumping syndrome precipitated by ingestion of simple sugars and fats, and a degree of malabsorption [22, 23].

The techniques of open and LRYGB are not standardized, and variations exist between centers. The GJA is traditionally created in a retrocolic retrogastric fashion in open RYGB. In the minimally invasive era, several techniques are used, including antecolic antegastric, retrocolic antegastric, or retrocolic retrogastric approaches [4, 8, 11, 15, 24]. It is technically easier to bring the alimentary limb anterior to the transverse colon rather than creating a retrocolic tunnel, which can be time consuming and inherently hazardous with bleeding from the often bulky mesocolon in the morbidly obese patient [4]. Some surgeons continue to routinely use a retrocolic retrogastric approach to reduce tension on the GJA, particularly in superobese patients with a bulky greater omentum or in those with a foreshortened small intestinal mesentery [25]. The retrocolic defect can be closed in an interrupted fashion, a continuous fashion, or not at all [8, 14, 26]. Other mesenteric defects including the jejunojejunal and Petersen’s space (retro-Roux loop) can be closed or left open [4, 11]. Absorbable or nonabsorbable suture can be used to close the mesenteric defects [11, 14]. The length of the alimentary limb is also not standardized and varies from 75 to 200 cm, according to individual patient’s body mass index and surgeon preference [4, 24]. The jejunal mesentery can be divided to lengthen the roux limb or not [4, 8]. An antikink suture, otherwise known as a Brolin stitch, can be routinely or selectively inserted after the completion of the jejunojejunostomy [8, 27]. The roux limb can be fixed or not when a retrocolic approach is used [11, 26]. The greater omentum can be divided to reduce tension on the GJA, not divided, or a window can be created in it for the roux limb [15]. Circular staplers, linear staplers, handsewn techniques, or a combination of these can be used to create and close the gastrojejunal and jejunojejunal anastomoses [4, 6, 28]. Finally, trocar sites may or may not be closed [4].

Clinical Evaluation

There are many causes of SBO after LRYGB (Table 1). The most common etiologies include iatrogenic causes because of narrow anastomoses, overzealous closure of mesenteric defects, mesenteric or intramural hematoma, anastomotic leak, incarcerated ventral hernias, internal hernias, and adhesions. Depending on the cause, patients develop symptoms in the immediate postoperative period, in the weeks after surgery, months, or even years later. Obstruction can involve the alimentary limb, biliopancreatic limb, common channel, or more distally if adhesive in nature. Because of the differences in surgical technique, the incidence of SBO varies from 0.4% to 7.45% [3]. With the adoption of the laparoscopic approach, there has been a reduction in postoperative SBO secondary to adhesions and incisional hernias. However, a higher incidence of SBO because of internal hernias is seen compared to the open procedure [12, 13]. Early series of laparoscopic bypass reported an incidence of SBO of 1.5–3.5% with most attributed to internal hernias but with a short follow-up period of less than 2 years [7, 29]. Internal herniation can occur at the jejunojejunostomy, Petersen’s space, or the transverse mesocolonic defect after a retrocolic approach. The incidence of internal hernias is higher after the retrocolic retrogastric approach and has been significantly reduced by adoption of the antecolic antegastric approach in reported series from 4.5% to 0.43% [15].

Patients can present acutely with the classical symptoms and signs of SBO or chronically with vague symptoms. Late SBO typically presents with intermittent, recurrent cramping periumbilical pain, which may be associated with intermittent nausea and vomiting. Not uncommonly, patients present to their local emergency room or primary care physician with recurrent vague symptoms and often their complaints are explained by failure to comply with diet, gastroesophageal reflux disease, postprandial pain, or marginal ulceration. Diagnosis is based on symptoms, clinical examination, and investigative tools including blood tests, plain abdominal radiographs, upper gastrointestinal contrast studies, and abdominal computed tomography scans (Tables 2 and 3). A methodical approach facilitates the identification of the site of obstruction in the majority of patients before surgery. Although symptoms are often similar, the presence of gastroesophageal reflux and significant vomiting is suggestive of an obstruction to the alimentary limb or common channel. Distention of the biliopancreatic limb and gastric remnant with elevated liver function tests and hyperamylasemia is suggestive of obstruction of the biliopancreatic limb or common channel (Table 3). Treatment is directed by the clinical condition of the patient and involves nasogastric decompression with early surgical intervention in the form of diagnostic laparoscopy.

Classification Systems

Numerous descriptive terms have been employed in an attempt to classify SBO after LRYGB in reported series based on presentation, onset after surgery, extent of obstruction, or anatomical site (Table 4) [8, 9, 14, 24]. The most commonly used method has been onset of symptoms in relation to duration after surgery in terms of early or late presentation [8, 9, 14, 24]. However, published classification systems of early presentation of SBO range from <3 weeks to <3 months, and similarly late presentation range from >3 weeks to >3 months (Table 5). It is clear that a simplified classification system is required. This would facilitate a uniform system of interpretation, understanding, and diagnosis of SBO after RYGB in the emergency room and facilitate more effective communication between nonbariatric surgeons in the general community with specialists in bariatric centers. An easily applicable system of classification would also enable uniform reporting of data and would allow comparison of postoperative morbidity among bariatric centers. This classification system would also permit a clearer understanding of the nature of the SBO after RYGB with more effective communication between bariatric specialists and accurate reporting of data with increased clarity of data analysis in the published literature.

Our proposed classification system is based on the anatomical site of obstruction, and onset of symptoms from the date of surgery (Tables 5, 6, and 7). With regard to the anatomical site of obstruction, we propose the following classification: type A, alimentary limb obstruction; type B, biliopancreatic limb obstruction; and type C, common channel obstruction (Table 5; Figs. 1 and 2). The time to SBO varies from 0 to 1,414 days after LRYGB in reported series with 44–48% occurring within the first month (Table 7) [8, 9, 14, 15, 24, 30]. In terms of the timing of onset of SBO after surgery, we propose the following additional classification system: acute early SBO, ≤30 days after LRYGB; acute late SBO, ≥30 days and <12 months after LRYGB; and chronic SBO, ≥12 months after LRYGB (Table 8).

The ABC system of classification of small bowel obstruction based on site of anatomic obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. A Alimentary limb, B biliopancreatic limb, C Common channel. With permission from the Journal of the American College of Surgeons and Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

Summary

Early diagnosis and treatment of SBO after LRYGB is crucial to avoid the development of catastrophic complications including anastomotic dehiscence, staple line disruption, small bowel ischemia, infarction, and gangrene. It is important to recognize that the most common cause of SBO after LRYGB is internal herniation, which will result in intestinal ischemia, perforation with peritonitis, sepsis, and death if not managed in a timely and appropriate fashion. Our proposed simplified classification system of SBO after LRYGB, based on the anatomical location of the obstruction and onset after surgery, will facilitate a better understanding of the underlying pathology and allow more effective communication between the nonbariatric and bariatric surgical community to ultimately improve patient management and outcome.

References

Anonymous. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. NIH consensus development conference, March 25–7,1991. Nutrition 1996;12(6):397–404.

Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(7):547–59.

Jones KB Jr, Afram JD, Benotti PN, et al. Open versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a comparative study of over 25,000 open cases and the major laparoscopic bariatric reported series. Obes Surg 2006;16(6):721–7.

Rosenthal RJ, Szomstein S, Kennedy CI, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for morbid obesity: 1,001 consecutive bariatric operations performed at the Bariatric Institute, Cleveland Clinic Florida. Obes Surg 2006;16(2):119–24.

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2001;234(3):279–89.

Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T. Complications of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 1,040 patients—what have we learned? Obes Surg 2000;10(6):509–13.

Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T, Davies OG. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: technique and preliminary results of our first 400 patients. Arch Surg 2000;135(9):1029–33.

Hwang RF, Swartz DE, Felix EL. Causes of small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2004;18(11):1631–5.

Cho M, Carrodeguas L, Pinto D, et al. Diagnosis and management of partial small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic antecolic antegastric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202(2):262–8.

Ukleja A, Stone RL. Medical and gastroenterologic management of the post-bariatric surgery patient. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38(4):312–21.

Higa KD, Ho T, Boone KB. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, treatment and prevention. Obes Surg 2003;13(3):350–4.

Podnos YD, Jimenez JC, Wilson SE, et al. Complications after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a review of 3464 cases. Arch Surg 2003;138(9):957–61.

Brolin RE. Laparoscopic verses open gastric bypass to treat morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2004;239(4):438–40.

Felsher J, Brodsky J, Brody F. Small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgery 2003;134(3):501–5.

Champion JK, Williams M. Small bowel obstruction and internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2003;13(4):596–600.

Macgregor AM. Small bowel obstruction following gastric bypass. Obes Surg 1992;2(4):333–9.

Mason EE, Ito C. Gastric bypass in obesity. Surg Clin North Am 1967;47(6):1345–51.

Nguyen NT, Silver M, Robinson M, et al. Result of a national audit of bariatric surgery performed at academic centers: a 2004 University Health System Consortium Benchmarking Project. Arch Surg 2006;141(5):445–9.

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y: preliminary report of five cases. Obes Surg 1994;4(4):353–7.

DeMaria EJ, Jamal MK. Surgical options for obesity. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34(1):127–42.

Shikora SA. Severe obesity: a growing health concern A.S.P.E.N. should not ignore. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005;29(4):288–97.

Alvarez-Leite JI. Nutrient deficiencies secondary to bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004;7(5):569–75.

Lynch RJ, Eisenberg D, Bell RL. Metabolic consequences of bariatric surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006;40(8):659–68.

Nguyen NT, Huerta S, Gelfand D, et al. Bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2004;14(2):190–6.

Ali MR, Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ. Techniques of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Semin Laparosc Surg 2002;9(2):94–104.

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y 500 patients: technique and results with a 360 month follow-up. Obes Surg 2000;10(3):233–9.

Brolin RE. The antiobstruction stitch in stapled Roux-en-Y enteroenterostomy. Am J Surg 1995;169(3):355–7.

Nguyen NT, Neuhaus AM, Ho HS, et al. A prospective evaluation of intracorporeal laparoscopic small bowel anastomosis during gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2001;11(2):196–9.

Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, et al. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2000;232(4):515–29.

Lauter DM. Treatment of nonadhesive bowel obstruction following gastric bypass. Am J Surg 2005;189(5):532–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tucker, O.N., Escalante-Tattersfield, T., Szomstein, S. et al. The ABC System: A Simplified Classification System for Small Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. OBES SURG 17, 1549–1554 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9273-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9273-1