ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among Hispanics in the United States (US), yet the use of CRC screening is low in this population. Physician recommendation has consistently shown to improve CRC screening.

OBJECTIVE

To identify the characteristics of Hispanic patients who adhere or do not adhere to their physician’s recommendation to have a screening colonoscopy.

DESIGN

A cross-sectional study featuring face-to-face interviews by culturally matched interviewers was conducted in primary healthcare clinics and community centers in New York City.

PARTICIPANTS

Four hundred Hispanic men and women aged 50 or older, at average risk for CRC, were interviewed. Two hundred and eighty (70%) reported receipt of a physician’s recommendation for screening colonoscopy and are included in this study.

MAIN MEASURES

Dependent variable: self report of having had screening colonoscopy. Independent variables: sociodemographics, healthcare and health promotion factors.

KEY RESULTS

Of the 280 participants, 25% did not adhere to their physician’s recommendation. Factors found to be associated with non-adherence were younger age, being born in the US, preference for completing interviews in English, higher acculturation, and greater reported fear of colonoscopy testing. The source of colonoscopy recommendation (whether it came from their usual healthcare provider or not, and whether it occurred in a community or academic healthcare facility) for CRC screening was not associated with adherence.

CONCLUSIONS

This study indicates that potentially identifiable subgroups of Hispanics may be less likely to follow their physician recommendation to have a screening colonoscopy and thus may decrease their likelihood of an early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Raising physicians’ awareness to such patients’ characteristics could help them anticipate patients who may be less adherent and who may need additional encouragement to undergo screening colonoscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a serious health problem among Hispanics in the United States. It is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among Hispanic men and women.1 Colorectal cancer screening has been demonstrated to be an effective tool in decreasing colorectal cancer incidence and is consistently recommended by clinical practice guidelines.2–6 However, the use of CRC screening among Hispanics is low, as only 31.9% of Hispanics report having had a screening test for CRC.1 This low CRC-screening rate may contribute to Hispanics’ later stage of disease at presentation and poorer prognosis than non-Hispanic Whites.7–11

Many studies have investigated the problem of low overall screening rates among Hispanics.12–18 Some have focused on the patient’s perspective and explored a wide spectrum of social, cultural and behavioral factors that could play a role in modifying patients’ willingness to undergo CRC screening. Others have examined system and healthcare access factors that could serve as facilitators or barriers to having CRC screening. Although different factors have been found to influence patients’ screening behavior, the majority of these studies have persistently shown that a physician recommendation is a critical predictor of undergoing a CRC screening test.12,19

Intervention programs created to encourage physicians to recommend CRC screening to patients have been effective in increasing screening rates among patients.20–34 These findings have opened a window of opportunity to increase CRC screening rates by changing healthcare professionals’ practice rather than depending solely on patients’ own motivation to undergo screening. Various plans have been proposed to change primary care practice in ways that would make it easier and more consistent for physicians to recommend CRC screening to their patients. Some examples of these plans include electronic reminders, team-based healthcare delivery, and insurance incentives. However, the literature is scarce when it comes to following up patients who received a physician recommendation to undergo CRC screening test but did not follow through, especially among Hispanics.

Previous studies focused on characteristics of Hispanics who did versus those who did not receive CRC screening.35 This study goes beyond this focus to investigate characteristics of Hispanics who do not adhere to their physician recommendation for CRC screening via colonoscopy versus those who do. Thus, in the present study, self-reported colonoscopy after receipt of physician recommendation is the dependent variable. Identifying the characteristics of non-adherers may present an opportunity for improving CRC screening rates through more specific intervention strategies.

METHODS

This study is a sub-study to a larger parent study. As previously reported in the parent study,35 this IRB approved cross-sectional survey was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained bilingual, Hispanic health educators from January 2008 to January 2009. Recruitment was conducted at three East Harlem health clinics and several community-based sites in New York City (NYC). Potential participants for the study were given a flyer describing the study (by staff at each site and/or project staff). If interested, project staff then described the study in greater detail; in either English or Spanish, and asked if they were interested in the study, and if so, determined their eligibility. Participants were told that The Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Hispanic project was being conducted at Mount Sinai and sponsored by the National Institute of Health with the purpose of identifying factors associated with Hispanics’ readiness to undergo colorectal cancer screening colonoscopies, and screening awareness and knowledge in general.

Inclusion criteria were (a) self-identified Hispanic or Latino, (b) at least 50 years of age, (c) English or Spanish speaking and (d) at an average risk of CRC. Average risk was defined as (i) no previous CRC history, (ii) no immediate family member with CRC, and (iii) no personal history of chronic gastrointestinal disease.

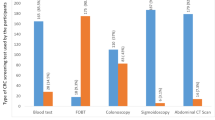

Although there are other methods of CRC screening, such as fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, and double contrast barium enema, we focused on colonoscopy because it is the gold standard for CRC screening and is widely available and promoted in NYC.36,37

Each participant received a study pen, a Center for Disease Control and Prevention brochure on CRC, and a $20.00 incentive. The 50-minute structured interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish (based on participant preference). Of the 400 participants in the parent study, 280 (70%) reported they had received a recommendation to undergo screening colonoscopy and thus were the focus of this study.

MEASURES

For measures requiring translation we used forward and back translation procedures to ensure content equivalency between English and Spanish.

Sociodemographics

Age, gender, income, marital status, employment status, education, place of birth, knowledge about colon cancer and years lived in the US were assessed, as well as language in which the interview was completed, having a regular health care provider, level of satisfaction with the received medical care and insurance coverage.

Physician Variables

Physician Recommendation and Encouragement

Participants were asked if their provider had ever recommended that they have a colonoscopy (Yes/No)38 and rated their provider’s encouragement for colonoscopy.39

Preferred Provider’s Language, Race or Ethnicity

Participants were asked whether they preferred their provider to speak Spanish, English, had no preference, or other. Participants were also asked if they would prefer their doctor to be of a certain race or ethnicity. The options were open ended or “No Preference.”

Organizational Access to Care

Participants rated different components of their interaction with their healthcare provider using the six-item Organizational Access to Care Scale developed by Safran.40 Questions about convenience of the provider’s office location, ability to schedule appointments, ability to get through to the doctor on the phone, waiting time and others were assessed.

Cultural Variables

Acculturation

The 12-item Acculturation Scale for Hispanics41 assessed language use, media preference and ethnic social relations (e.g., “What language(s) do you usually speak with your friends?”) Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (Only Spanish) to 5 (Only English). One additional item was added (“What language(s) does your doctor/provider speak?”)

Medical Mistrust

With the 12-item Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale42,43 participants rated their beliefs about the care they received from health care providers (e.g., “Hispanics/Latinos(as) should be suspicious of modern medicine.”)

Emotional Variables

Fear of Colonoscopy

A six-item scale developed by Manne (personal communication, 2005) assessed fear of aspects of the colonoscopy procedure and its results. Items (e.g., “How fearful are you of the overall colonoscopy procedure”) were rated on a five-point Likert scale.

Attitudinal Variables

Pros and Cons

The Pros and Cons Scale for CRC developed by Manne and colleagues44 with nine items indicating the benefits (Pros) of colonoscopy and 19 items indicating the barriers (Cons) to colonoscopy was administered. Four additional items, based on our prior research,35 were added to address machismo (“Having a colonoscopy would make me feel like less of a man/woman”), embarrassment, and two items to address salience-coherence regarding a colonoscopy (e.g., “Having a colonoscopy makes sense to me”).

ANALYSIS PLAN

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 software package. Categorical data were analyzed by Chi-square analysis and continuous data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Logistic Regression was used to analyze variables in the multivariate analyses. All tests of significance were two-sided using a P value of 0.05. Sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, education, years lived in US) were first analyzed through Student’s t-test, then recoded for Chi-square analyses to obtain odd ratios and confidence intervals. Participants’ age was dichotomized (those less than 65 vs. those more than 65 years of age). Prior research has shown that those who were 65 years and older had higher rates of CRC screening as compared with younger people.15 Other variables included level of education (above or below the mean education level of 9th grade) and years lived in the US (more or less than half of the participants’ lives). For most survey variables, there was no missing data. Missing values were minimal for income (2.5%) and choosing a provider based according to spoken language (5%). Participants who did not answer all scale questions were excluded from individual scale analysis. A multivariate logistic regression model was developed to evaluate the effect of different covariates on screening uptake. Variables that were thought to affect screening uptake were included in the model regardless of whether they were significant or not in the univariate analysis. The model included sociodemographic variables (age, education level, marital status, place of birth, proportion of life in US and preferred interview language), health care provider’s variables (preferred provider’s race, language, gender and level of doctor encouragement to undergo screening colonoscopy), cultural variables (acculturation, medical mistrust) and emotional and attitudinal variables (pros and cons and fear of screening colonoscopy).

RESULTS

A total of 400 Hispanic men and women were interviewed at primary health care and community centers in East Harlem, NYC. Of those, 280 (70%) reported receipt of a physician recommendation to have a screening colonoscopy and were included in the study. Their sociodemographic and health care characteristics are summarized in Table 1, which also includes univariate results for the sample by screening colonoscopy status (Group A reported having completed a colonoscopy, Group B did not complete a colonoscopy).

Characteristics of the non-adherent group of participants were analyzed and compared to those of the adherent group. When sociodemographic variables were analyzed three major differences were identified between the two groups: age, place of birth and preferred interview language (see Table 1).

Age was significantly different between the two groups with younger age being associated with more non-adherence to physician colonoscopy recommendation than older age (P < 0.001). Being born in the US and a preference for conducting the interview in English was associated with lower rates of screening colonoscopy than being born outside the US or a preference for conducting the interview in Spanish (P = 0.019, 0.008 respectively). Other sociodemographic factors (gender, level of education, marital status, income and other variables listed in Table 1) were not different between the two groups.

When cultural, emotional, organizational, and attitudinal variables were analyzed, two significant differences between the two groups were identified: level of fear of undergoing colonoscopy and acculturation (see Table 2).

Participants who did not adhere to their physician recommendation were more fearful of a colonoscopy (e.g., fear of possible cancer detection or of physical discomfort) than those who completed the test (P = 0.026). Also, greater acculturation to US culture was associated with less adherence to screening colonoscopy recommendations than lower acculturation (P = 0.029). Although acculturation is sometimes linked to the length of time lived in the US, the study did not show an association between the number of years lived in the US and adherence to screening colonoscopy (P = 0.248).

Factors that assessed participants’ interaction and experience with the healthcare system (e.g. health insurance, medical mistrust, satisfaction with care) were examined, but none were found to be different between the two groups.

Despite the fact that provider’s language has been cited to be an important predictor of Hispanics’ completion of screening45 and that a large number of our study participants preferred their provider to speak Spanish as compared to those who preferred English (47.1% vs 10.8%), neither the preferred nor the actual spoken language of the healthcare provider was associated with participants’ adherence to their provider’s screening recommendation (P = 0.391). Similarly, the preferred healthcare provider’s race or ethnicity was not associated with adherence.

In summary, the univariate analysis results showed five variables (age, place of birth, preferred interview language, fear of colonoscopy and acculturation) to be significantly associated with participants’ adherence to their provider’s recommendation to screening colonoscopy. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, where all relevant variables whether significant or not on the univariate analysis, were included in the model, two variables showed significant association with participants’ adherence to their provider’s recommendation: age (P < 0.001) and fear of undergoing CRC screening colonoscopy (marginally significant, P = 0.060). Younger age and greater fear of the test were associated with lower levels of adherence to physician recommendation to undergo a CRC screening colonoscopy.

DISCUSSION

Colorectal cancer among Hispanics in the United States is a significant health problem and may be affected by low CRC screening rates.1 Physician recommendation has consistently been found to be the most important motivator of having a screening colonoscopy, yet some Hispanic patients do not follow their physician’s advice.2–6 The current study examined characteristics of Hispanics who did and did not follow their physician recommendation to complete CRC screening via colonoscopy in an effort to identify and understand different subject, provider and system factors that may modify adherence.

The findings of this study are critical because they frame the characteristics of a potentially identifiable group of Hispanics who may be less likely to adhere to their physician recommendation. Being able to anticipate which patients may be less likely to adhere to physician recommendation could enable healthcare providers to plan a more tailored approach of delivering the recommendation to that group.

We found that the largest differences between participants who followed their physician’s advice to undergo screening colonoscopy and those who did not were the characteristics of the study participants, specifically, age, place of birth, acculturation level, fear of undergoing the test, and language preference. Younger age, being born in the US and a preference to be interviewed in English were associated with less follow through on the recommendation for a CRC screening than older age, being born outside of the US and a preference to be interviewed in Spanish. Although an earlier study did not find a relationship between acculturation and screening colonoscopy behavior,46 in this study, participants who reported being more acculturated to US customs reported less adherence to CRC screening.

Fear of the colonoscopy procedure was another factor related to participants’ reported adherence to screening colonoscopy. Physicians should be aware that some Hispanics may not undergo colonoscopy because they are worried about possible cancer detection or about expected physical discomfort. Physicians or staff should inquire about specific fears and concerns and address them when recommending a screening colonoscopy.

The above findings appear to be related to each other and also appear to revolve around one main variable: the participants’ age. Younger Hispanics were more likely to be US born and consequently may be more likely to prefer English and to be more acculturated to US customs (p < 0.001 for all three interactions). Possibly due to their age, younger people may be less likely to think about the possibility of being diagnosed with cancer and thus may be less inclined to undergo screening. This explanation is supported by the results of the multivariate analysis since age remained significant when all other covariates were controlled. Fear may also explain some of the obtained results. It might be that younger patients do not want to know or may be more afraid to find out that they have cancer and thus are less likely to undergo screening.

Both of these findings add more power to the main point of our study: we recognized a potentially identifiable sub-group of Hispanics who may be less likely to adhere to CRC screening recommendation. This sub-group consists of younger Hispanics who fear colonoscopy screening and/or are afraid to learn that they might have cancer. Therefore, more time needs to be spent with younger people to help them overcome their fear, address their concerns about colorectal cancer screening and encourage them to take the test.

Examining the relationship of having undergone colonoscopy or not with the characteristics of the healthcare provider resulted in encouraging findings. None of the physicians’ personal characteristics (race, ethnicity, gender, or spoken language) were associated with participants’ adherence to their physician recommendation. Furthermore, the source and setting of the physician recommendation was not associated with participants’ screening behaviors. No relationship was found between source of recommendation (whether usual healthcare provider, in a community or academic facility) and self-reported adherence. This suggests that if Hispanic patients receive a CRC screening recommendation from a physician, regardless of that physician’s race, gender, affiliation or spoken language, the likelihood that they would undergo screening colonoscopy is the same.

Healthcare system factors may play a less important role in determining participants’ completion of colonoscopy. This maybe influenced, however, by the fact that most of our participants had health insurance which presumably covered screening colonoscopy expenses. Studies that have explored system barriers to screening colonoscopy among Hispanics frequently cited either lack of insurance or lack of physician recommendation as main barriers,10,11 both of which are not applicable to this study.

Although our study has many strengths, there are some potential limitations. The results of this study may not apply to Hispanics who do not have health insurance and/or access to care. The dependent variable (screening colonoscopy) was indicated by participants’ self reports and may be subject to participants’ social desirability bias. Future research should include medical or billing record reviews. This study was also limited by its cross sectional design and causality could not be determined; longitudinal research could address this issue in the future. Finally, this study was conducted in only one community of Hispanics in NYC. Thus, the results may not generalize to Hispanics in different geographical locations and findings will need to be replicated to test their generalizability.

Physician recommendation has been found to be an important predictor of having a screening colonoscopy.12,19 Physician recommendation should be encouraged and efforts should be made to facilitate physician recommendation for screening colonoscopy. Participant factors associated with adherence to physician recommendation in Hispanics included being born outside the US, older age, and a preference to speak Spanish. This association remains strong regardless of the physician’s race, gender, or affiliation, even when that recommendation did not come from the patient’s regular provider. Additional time might need to be spent with younger US born Hispanics to address any possible fear or concerns and to encourage CRC screening; otherwise they may be less likely to complete their screening and thus may be vulnerable to develop CRC. If the same findings were replicated in nationwide studies, the new generation of Hispanics in the United States who may be less likely to follow their physician recommendations for screening colonoscopy could be more vulnerable to develop CRC than their immigrant parents.

References

American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009–2011. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/ffhispanicslatinos20092011.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1681–8.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):99–119.

Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–60.

Pignone M, Levin B. Recent developments in colorectal cancer screening and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(2):297–302.

Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(2):132–41.

National Cancer Institute. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2007. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/index.html. Accessed April 11, 2011.

Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544–73.

Hoffman-Goetz L, Breen NL, Meissner H. The impact of social class on the use of cancer screening within three racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Ethn Dis. 1998;8(1):43–51.

Gilliland F, Hunt W, Key C. Trends in the survival of American Indian, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic white cancer patients in New Mexico and Arizona, 1969–1994. Cancer. 1998;82(9):1769–83.

Green AR, Peters-Lewis A, Percac-Lima S, et al. Barriers to screening colonoscopy for low-income Latino and white patients in an urban community health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):834–40.

Cameron KA, Francis L, Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Investigating Hispanic/Latino perceptions about colorectal cancer screening: A community-based approach to effective message design. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(2):145–152.

Pollack LA, Blackman DK, Wilson KM, Seeff LC, Nadel MR. Colorectal cancer test use among Hispanic and non-Hispanic U.S. populations. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A50.

James TM, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Feng C, Ahluwalia JS. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline based analysis of adherence. Ethnic Dis. 2006;16(1):228–233.

Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–394.

Thompson B, Coronado G, Neuhouser M, Chen L. Colorectal carcinoma screening among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in a rural setting. Cancer. 2005;103(12):2491–8.

Ioannou GN, Chapko MK, Dominitz JA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening participation in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(9):2082–2091.

Fernandez ME, Wippold R, Torres-Vigil I, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among Latinos from U.S. cities along the Texas–Mexico border. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:195–206.

Geiger TM, Miedema BW, Geana MV, Thaler K, Rangnekar NJ, Cameron GT. Improving rates for screening colonoscopy: analysis of the health information national trends survey (HINTS I) data. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:527–533.

Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Marshall R, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. Patient and physician reminders to promote colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(4):364–371.

Lane DS, Messina CR, Cavanagh MF, Chen JJ. A provider intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in county health centers. Med Care. 2008;46:S109–16.

Zapka JG, Puleo E, Vickers-Lahti M, Luckmann R. Healthcare system factors and colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1):28–35.

Nease DE Jr, Ruffin MT 4th, Klinkman MS, Jimbo M, Braun TM, Underwood JM. Impact of a generalizable reminder system on colorectal cancer screening in diverse primary care practices. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S86–73.

Wei EK, Ryan CT, Dietrich AJ, Colditz GA. Improving colorectal cancer screening by targeting office systems in primary care practices. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:661–6.

Klabunde CN, Lanier D, Breslau ES, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening in primary care practice: innovative strategies and future directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1195–1205.

Sabatino SA, Habarta N, Baron RC, et al. Interventions to increase recommendation and delivery of screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by healthcare providers. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1S):S67–S74.

Ling BS, Schoen RE, Trauth JM, et al. Physicians encouraging colorectal screening: a randomized controlled trial of enhanced office and patient management on compliance with colorectal cancer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(1):47–55.

Ayanian JZ, Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Johannes RS. Physician reminders to promote surveillance colonoscopy for colorectal adenomas: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):762–7.

Sansbury LB, Klabunde CN, Mysliwiec P, Brown ML. Physicians’ use of nonphysician healthcare providers for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3):179–186.

Hudson SV, Ohman-Strickland P, Cunningham R, Ferrante JM, Hahn K, Crabtree BF. The effects of teamwork and system support on colorectal cancer screening in primary care practices. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(5):417–23.

Seres KA, Kirkpatrick AC, Tierney WM. The utility of an evidence-based lecture and clinical prompt as methods to improve quality of care in colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):420–5.

Ye J, Xu Z, Aladesanmi O. Provider recommendation for colorectal cancer screening: examining the role of patients’ socioeconomic status and health insurance. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33(3–4):207–11.

Janz NK, Lakhani I, Vijan S, Hawley ST, Chung LK, Katz SJ. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening use, attempts, and non-use. Prev Med. 2007;44(5):452–8.

Jerant A, Kravitz RL, Rooney M, Amerson S, Kreuter M, Franks P. Effects of a tailored interactive multimedia computer program on determinants of colorectal cancer screening: A randomized controlled pilot study in physician offices. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(1):67–74.

Jandorf L, Ellison J, Villagra C, et al. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among low income immigrant Hispanics. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):462–9.

Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Haford WV, et al. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal-occult testing and examination of the distal colon. N Eng J Med. 2001;345(8):555–60.

Levin B, Lieberman D, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2008;30(2):133–46.

Cokkinides VE, Chao A, Smith RA, Vernon SW, Thun MJ. Correlates of underutilization of colorectal cancer screening among U.S. adults, age 50 years and older. Prev Med. 2003;36:85–91.

Myers RE, Trock BJ, Lerman C, Wolf T, Ross E, Engstrom PF. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an HMO population. Prev Med. 1998;19:502–14.

Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–39.

Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jandorf L, Redd W. Perceived disadvantages and concerns about abuses of genetic testing for cancer risk: differences across African American, Latina and Caucasian women. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:217–27.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The group-based medical mistrust scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38:209–18.

Manne S, Markowitz A, Winawer S, et al. Correlates of colorectal cancer screening compliance and stage of adoption among siblings of individuals with early onset colorectal cancer. Health Psychol. 2002;21:3–15.

Natale-Pereira A, Marks J, Vega M, Mouzon D, Hudson SV, Salas-Lopez D. Barriers and facilitators for colorectal cancer screening practices in the Latino community: perspectives from community leaders. Cancer Control. 2008;15(2):157–65.

Shah M, Zhu K, Potter J. Hispanic acculturation and utilization of colorectal cancer screening in the United States. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(3):306–12.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend thanks to the study participants, and the study sites, the East Harlem community, and the East Harlem Partnership for Cancer Awareness’ Community Advisory Board for their insight and support. The authors would also like to thank Simay Gokbayrak for her assistance throughout the writing of this paper. This project was supported by Grant No. R21 CA119016 from the National Institutes of Health. A presentation on the results from the parent study included some of these findings with a smaller sample size (prior to data completion) entitled: “Patient–Provider Interaction Effects on Colorectal Cancer Screening among Urban Hispanics” presented at the Public Health Association of New York City’s (PHANYC) Fourth Annual Student Conference, New York, USA on June 14th, 2009.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jibara, G., Jandorf, L., Fodera, M.B. et al. Adherence to Physician Recommendation to Colorectal Cancer Screening Colonoscopy Among Hispanics. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 1124–1130 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1727-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1727-4