Abstract

Introduction

Safety-net hospitals provide care to an inherently underprivileged patient population. These hospitals have previously been shown to have inferior surgical outcomes after complex, elective procedures, but little is known about how hospital payer-mix correlates with outcomes after more common, emergent operations.

Methods

The University HealthSystem Consortium database was queried for all emergency general surgery procedures performed from 2009 to 2015. Emergency general surgery was defined as the seven operative procedures recently identified as contributing most to the national burden. Only urgent and emergent admissions were included (n = 653,305). Procedure-specific cohorts were created and hospitals were grouped according to safety-net burden. Multivariate analyses were done to study the effect of safety-net burden on hospital outcomes.

Results

For all seven emergency procedures, patients at hospitals with a high safety-net burden were more likely to be young and black (p < 0.01 each). Patients at high-burden hospitals had similar severity of illness scores to those at other hospitals. Compared with lower burden hospitals, in-hospital mortality rates at high-burden hospitals were similar or lower in five of seven procedures (p = NS or < 0.01, respectively). After adjusting for patient factors, high-burden hospitals had similar or lower odds of readmission in six of seven procedures, hospital length of stay in four of seven procedures, and cost of care in three of seven procedures (p = NS or < 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

Safety-net hospitals provide emergency general surgery services without compromising patient outcomes or incurring greater healthcare resources. These data may help inform the vital role these institutions play in the healthcare of vulnerable patients in the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Safety-net hospitals provide healthcare and health-related services to disadvantaged populations, including the uninsured and Medicaid beneficiaries.1,2,3 These organizations provide necessary but often unprofitable services to these vulnerable patients.4 As a result, hospitals with a high safety-net burden have relied heavily on federal funding and other government subsidies, such as the Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program, to help cover their financial losses.5

In an effort to offset these losses, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into US healthcare policy on March 23, 2010. The primary aim of the ACA was to increase access to quality care by mandating health insurance and expanding Medicaid coverage among vulnerable populations.6 However, the consequences of this law have yet to be fully realized. While nearly 17 million more Americans have become insured since its enactment7, Medicaid reimbursements are lower than the cost of care, and many states have actively impeded its expansion.8,9 Moreover, the ACA has called for a $30 to $50 billion reduction in DSH funding, further decreasing repayment to hospitals serving impoverished patients.8,9 Due to these changes and an insecure future for healthcare policy and reimbursement, safety-net hospitals face growing concerns regarding their financial stability.5,9,10

Given the dynamic landscape of current healthcare delivery in the USA, surprisingly little is known about how hospital payer-mix affects outcomes in common, emergent surgical procedures. We must understand the role safety-net hospitals play in the delivery of emergency general surgery (EGS) services in order to inform any future changes to healthcare policy. In the present study, we analyzed the effect of safety-net burden on surgical outcomes and hospital resource utilization after EGS procedures. We hypothesized that hospitals with greater safety-net burden would have inferior outcomes, owing to systemic deficiencies and limited resources.3

Methods

Data Sources

The primary data source for the study was the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) Clinical Database and Resource Manager. The UHC represents a nonprofit alliance of 118 academic medical centers and 298 of their associated hospitals. Data collected by the UHC include International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnoses, patient demographics, financial data, and procedural data. Estimated cost of care for each patient encounter is calculated using hospital-specific, Medicare cost-to-charge ratios and federally reported wage indices, as previously described.11,12 Complete UHC data were available for the study period from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2015.

Patients undergoing EGS procedures during the study period were identified using ICD-9 procedural codes (Table 1). We chose to study a cohort of seven procedures previously defined and validated by Scott et al. as representing approximately 80% of all admissions, complications, deaths, and cost of care for EGS in the USA.13 Patients were divided into seven cohorts based on procedure type. Of note, patients were categorized according to primary procedure code; thus, patients included in the laparotomy cohort were not included in other procedure cohorts. These patients had diagnoses including “acute vascular insufficiency of intestine”, “peritoneal abscess”, “nontraumatic hemoperitoneum”, “paralytic ileus”, or “other unspecified intestinal disorders” and underwent laparotomy without concomitant small bowel resection or partial colectomy. Patients undergoing small bowel resection were most commonly noted to carry diagnoses of “intestinal or peritoneal adhesions with obstruction”, “acute vascular insufficiency of intestine”, “incisional hernia with obstruction”, “unspecified intestinal obstruction”, or “perforation of intestine”. Patients undergoing partial colectomy were most commonly noted to carry diagnoses of “diverticulitis of colon”, “volvulus”, “acute vascular insufficiency of intestine”, “perforation of intestine”, or diagnoses related to presence of malignant neoplasms. Only urgent and emergent admissions were included in the study. Trauma admissions and patients aged < 18 years were excluded from analysis.

Variables Defined

The following data were collected from the UHC database: age, race (white, black, Asian, Hispanic, or other), gender, severity of illness (SOI) scores, insurance type (private, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured, or other), overall hospital length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, 30-day readmission, discharge disposition, and total direct cost. SOI scores, which estimate the degree of physiologic decompensation for each patient on admission, are derived from a proprietary formula that is based on all payer refined diagnoses related groups and has been validated in a nationwide database that included 8.5 million discharges from more than 1000 hospitals.14 These scores classify patients into minor, moderate, major, or extreme groups and are used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to define and measure hospital case-mix complexity.15 Readmissions were defined as those occuring within 30 days of the index admission discharge date.

Safety-net burden was used to group hospitals, as previously described.2,3 Briefly, hospital safety-net burden was defined as the percentage of all inpatient discharges during the study period that were either uninsured or covered by Medicaid. Hospitals were stratified into low-burden (LBH), middle-burden (MBH), and high-burden (HBH) groups based on their safety-net burden: LBHs included hospitals in the lowest quartile; MBHs, in the middle two quartiles; and HBHs, in the highest quartile of safety-net discharges. Safety-net hospitals were represented by the HBH cohort.

Statistical Analysis

For univariate analysis, categorical data were compared using χ2 tests and are described as percentages (%). Continuous data were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and are described as median values with interquartile ratio (IQR) where applicable. For multivariate analysis, several statistical models were utilized. Predictors of readmission were calculated as odds ratios (OR), while predictors of cost of care and hospital LOS were calculated as risk ratios (RR). These models were adjusted for patient factors, including age, race, insurance type, and SOI scores. A random-effects model was used in all analyses in order to account for patient clustering.

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical packages JMP Pro 11 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati.

Results

Study Population

A total of 310 hospitals were included in the analysis. After stratification, 79 were identified as LBHs, 153 as MBHs, and 78 as HBHs. A total of 653,305 procedures were performed during the study period. Cases identified include appendectomy (n = 115,558), cholecystectomy (n = 192,182), laparotomy (n = 60,329), lysis of peritoneal adhesions (n = 141,466), partial colectomy (n = 70,933), peptic ulcer disease (PUD) repair (n = 9643), and small bowel resection (n = 63,194).

Demographic information and patient outcomes after EGS procedures are highlighted in Table 2. For all seven procedures, patients at HBHs were more likely to be black race and younger than those presenting to LBHs (p < 0.01 each). For five of seven procedures, patients at HBHs were more likely to be male gender (p < 0.01 each). Patients at HBH had similar severity of illness scores to those at other hospitals.

Surgical Outcomes

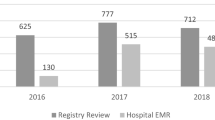

Surgical outcomes at HBHs were non-inferior to their lower burden counterparts on univariate analysis. For five of seven procedures analyzed, HBHs had similar or lower in-hospital mortality rates (p = NS or < 0.01, respectively). For six of seven procedures, hospital LOS was equal or shorter in HBHs (p = NS or < 0.01, respectively). For all seven procedures, readmission rates were lower at HBHs (p < 0.05 each). With regard to cost, four of seven procedures were found to be costlier at HBHs (p < 0.01 each). After adjusting for covariates (Table 3, Fig. 1), HBHs had similar or lower odds of readmission in six of seven procedures, hospital LOS in four of seven procedures, and cost of care in three of seven procedures (p = NS or < 0.01, respectively).

Discussion

Safety-net hospitals provide a broad range of care to socially disadvantaged patients. These hospitals have traditionally depended on government subsidies to remain financially viable, but with the enactment of the ACA, healthcare repayment systems are undergoing considerable reform. Evidence is limited on how these changes in federal funding will affect the provision of healthcare services to vulnerable populations. In the current study, we found that safety-net hospitals provide EGS services to these populations without compromising patient outcomes or incurring greater resources.

EGS hospitalizations constitute a significant fraction of US healthcare spending. These common surgical procedures account for over 3 million admissions and $28 billion in healthcare expenditure each year.16,17,18,19 Comparatively, the total costs of EGS exceed those of treating diabetes, myocardial infarctions, and all new cancer diagnoses combined.16,20 These costs are projected to increase dramatically in coming years, with some experts designating EGS as an impending public health crisis.20 A recent study by Scott et al. found that seven commonly performed operations—adhesiolysis, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, laparotomy, partial colectomy, small bowel resection, and operative management of PUD—account for 80% of EGS-related admissions, costs, morbidity, and mortality.13 Naturally, the authors contend that these seven procedures should be the focus of quality improvement and cost reduction efforts.

Safety-net hospitals are tasked with providing quality EGS services to vulnerable patients. Previous studies have found that HBHs deliver less efficient care, perform worse on Surgical Care Improvement Project measures, and have higher rates of surgical complications.3 Despite these deficiencies, in the current study, we found that HBHs achieve similar outcomes and costs after EGS as compared to lower burden hospitals. This differs from complex elective operations, where outcomes are inferior and hospital costs are greater, independent of patient factors.2,3 The reasons underlying this discrepancy are likely multifactorial. One explanation is that lower burden hospitals have more experience with major, elective cases as compared with emergent procedures. Another potential explanation is that surgeons at HBHs have learned to work with their institutional shortcomings in emergent procedures, but are limited by available services for complex, elective operations. Hospital characteristics including subspecialty accreditation, surgeon experience, intensive care resources, bed count, staff-to-patient ratio, teaching status or trainee presence, and geographical location were beyond the scope of the current study, but represent additional factors that may impact outcomes. Ultimately, understanding the reasons behind this discrepancy between EGS and elective complex surgery is crucial for improving quality of care at safety-net hospitals.

Readmission rates are another major focus of surgical quality improvement efforts.21,22 As part of the ACA, in 2012, the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program implemented financial disincentives for hospitals with excess readmission rates.23 This policy change sparked backlash amidst growing concerns that safety-net hospitals would be disproportionately penalized for higher readmission rates, exacerbating preexisting disparities in care.24,25,26,27 For emergent surgical hospitalizations, we found that HBHs subvert expectations and achieve lower readmission rates after all seven procedures. Again, these findings differ from major, elective procedures, where readmission rates are higher among safety-net hospitals.3 These findings persist after accounting for patient factors, suggesting that intrinsic qualities of HBHs may be accountable for this discrepancy between elective and emergent cases.

The current state of the healthcare industry is fraught with financial disincentives for substandard outcomes, and safety-net hospitals may be disproportionately affected by these penalties. Moreover, financial strain negatively impacts the quality of care delivered, resulting in increased complications and mortality.28,29,30,31 Thus, the financial health of safety-net hospitals indirectly affects patient outcomes. One potential solution to this self-perpetuating problem is the regionalization of surgical procedures. Proponents of regionalization have argued that operative volume is a benchmark of surgical quality, and operative procedures should be referred to high-volume centers.32,33,34,35,36 While this is an attractive solution, volume-based referral has its drawbacks including fragmentation of care, reduction in eligible providers, and travel costs. A recent editorial contends that complex surgeries benefit from regionalization, while simple, low-risk surgeries are poor candidates for referral.32 Our findings, though lacking granular details regarding several patient and procedural measures, suggest that for emergent surgical cases, referral may not be required in all cases. Not only do safety-net hospitals achieve comparable outcomes after EGS cases, any referral delay with an emergent surgical indication may be detrimental to patient care.

Additional consideration must be given to the fact that safety-net hospitals consist of both academic and non-academic centers that may be urban or rural. With academic teaching institutions often having access to resources including critical care or acute care surgery specialists as well as receiving additional financial subsidies, ACA associated reductions in DSH payments estimated to be between $30 and $50 billion dollars from 2017 to 2024 may disproportionately affect non-academic safety-net hospitals.9 Hence, the cohort of hospitals included in the current study may not represent the most vulnerable institutions at risk for bearing the burden of uncompensated care delivery. Compounded by a lack of Medicaid expansion in certain states, DSH payment reductions may exacerbate financial concerns for both academic and non-academic safety-net institutions and force them to eliminate service lines critical to indigent patients. By examining which healthcare services are delivered adequately by these institutions, the current study serves to inform policymakers at the state level responsible for allocating Medicaid DSH funds. Further research utilizing data resources that capture outcomes at non-academic, rural safety-net hospitals would provide even greater insight into the effect DSH payment reductions may have on these susceptible institutions. It is important to note that while safety-net hospitals may achieve comparable outcomes, for four of the seven procedures examined in the current study, total direct costs for inpatient admissions were higher at HBHs. These findings suggest that while it remains critical to advocate for appropriate allocation of funds to financially susceptible HBHs, there may be inefficiencies in care delivery at these centers that require ongoing improvement and standardization. Conversely, meeting the demands of vulnerable patients with complex social needs and limited resources requires HBHs to offer costly services not needed by patients treated at lower burden centers.

Our results should be taken in context of their limitations. First is the retrospective nature of our analysis. Second, our results are derived from data collected through the UHC database. While this database contains information patient outcomes, such as in-hospital mortality and 30-day readmission rates, it fails to capture granular data on the reasons for death or readmission. Whether procedures were truly “emergent” or “urgent” was also unknown and subject to coding bias within the UHC database as specific scheduling reasons were not captured or available for analysis. As a result, cases that were urgencies of convenience for social or scheduling reasons may have been included with truly “emergent” or “urgent” cases in the study cohort. Additionally, readmissions to outside hospitals or different facilities may not be captured in the dataset. Hospital level characteristics including staff-to-patient ratio, bed count, teaching status, and geographical location were also unavailable for analysis and may represent institutional factors that may contribute to differences in outcomes. Third, the UHC database is limited to patients admitted at academic hospitals. Safety-net hospitals that are non-teaching, non-academic centers may be even more vulnerable than academic centers due to a lack of resources such as high-volume acute care surgery and critical care specialists. Given that a significant proportion of safety-net hospitals are urban academic medical centers, however, our results are likely representative of a large subset of safety-net hospitals nationwide.37

Conclusions

Safety-net hospitals provide indispensable healthcare services to millions of uninsured and underinsured patients, often sacrificing their own profitability for philanthropy. In the current study, we found that these institutions provide emergent surgical care to socially disadvantaged populations without jeopardizing patient outcomes or incurring greater healthcare costs. While US healthcare repayment systems have been subject to well-intended reform in recent years, safety-net hospitals have become disproportionately penalized by these changes. Future policy changes should strive to alleviate the financial strain placed on these institutions, in order to improve the quality of care provided to vulnerable populations in our country.

Abbreviations

- ACA:

-

Affordable Care Act

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DSH:

-

Disproportionate Share Hospital

- EGS:

-

emergency general surgery

- HBH:

-

high burden hospital

- LBH:

-

low burden hospital

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- MBH:

-

medium burden hospital

- NS:

-

not significant

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- PUD:

-

peptic ulcer disease

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SNH:

-

safety-net hospital

- SOI:

-

severity of illness

- UHC:

-

University HealthSystem Consortium

References

Schoniger-Hekele M, Muller C, Kutilek M, Oesterreicher C, Ferenci P, Gangl A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Central Europe: prognostic features and survival. Gut. 2001;48(1):103–109.

Go DE, Abbott DE, Wima K, et al. Addressing the High Costs of Pancreaticoduodenectomy at Safety-Net Hospitals. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):908–914.

Hoehn RS, Wima K, Vestal MA, et al. Effect of Hospital Safety-Net Burden on Cost and Outcomes After Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(2):120–128.

El-Serag HB, Siegel AB, Davila JA, et al. Treatment and outcomes of treating of hepatocellular carcinoma among Medicare recipients in the United States: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1):158–166.

Neuhausen K, Davis AC, Needleman J, Brook RH, Zingmond D, Roby DH. Disproportionate-share hospital payment reductions may threaten the financial stability of safety-net hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):988–996.

Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(1):130–135.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

Hoofnagle JH. Hepatocellular carcinoma: summary and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S319–323.

Cole ES, Walker D, Mora A, Diana ML. Identifying hospitals that may be at most financial risk from Medicaid disproportionate-share hospital payment cuts. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):2025–2033.

Yeung YP, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong BC, Fan ST, Wong J. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(9):1995–2004.

Quillin RC, 3rd, Wilson GC, Wima K, et al. Neighborhood level effects of socioeconomic status on liver transplant selection and recipient survival. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(11):1934–1941.

Wilson GC, Quillin RC, 3rd, Wima K, et al. Is liver transplantation safe and effective in elderly (>/=70 years) recipients? A case-controlled analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16(12):1088–1094.

Scott JW, Olufajo OA, Brat GA, et al. Use of National Burden to Define Operative Emergency General Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):e160480.

Jalisi S, Bearelly S, Abdillahi A, Truong MT. Outcomes in head and neck oncologic surgery at academic medical centers in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(3):689–698.

Horn SD, Horn RA, Sharkey PD. The Severity of Illness Index as a severity adjustment to diagnosis-related groups. Health Care Financ Rev. 1984;Suppl:33–45.

Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: A 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample--2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):202–208.

Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: National estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):444–448.

Ogola GO, Shafi S. Cost of specific emergency general surgery diseases and factors associated with high-cost patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(2):265–271.

Shah AA, Haider AH, Zogg CK, et al. National estimates of predictors of outcomes for emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):482–490; discussion 490–481.

Paul MG. The Public Health Crisis in Emergency General Surgery: Who Will Pay the Price and Bear the Burden? JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):e160640.

Lucas DJ, Pawlik TM. Readmission after surgery. Adv Surg. 2014;48:185–199.

Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(5):483–495.

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):693–699.

Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Wilson IB, Milstein AS, Becker ER. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1314–1322.

Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. The Financial Effect of Value-Based Purchasing and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on Safety-Net Hospitals in 2014: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):427–436.

Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

Sheingold SH, Zuckerman R, Shartzer A. Understanding Medicare Hospital Readmission Rates And Differing Penalties Between Safety-Net And Other Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):124–131.

Bazzoli GJ, Chen HF, Zhao M, Lindrooth RC. Hospital financial condition and the quality of patient care. Health Econ. 2008;17(8):977–995.

Encinosa WE, Bernard DM. Hospital finances and patient safety outcomes. Inquiry. 2005;42(1):60–72.

Lindrooth RC, Konetzka RT, Navathe AS, Zhu J, Chen W, Volpp K. The impact of profitability of hospital admissions on mortality. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 Pt 2):792–809.

McHugh M, Martin TC, Orwat J, Dyke KV. Medicare's policy to limit payment for hospital-acquired conditions: the impact on safety net providers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(2):638–647.

Chhabra KR, Dimick JB. Strategies for Improving Surgical Care: When Is Regionalization the Right Choice? JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1001–1002.

Colavita PD, Tsirline VB, Belyansky I, et al. Regionalization and outcomes of hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer surgery in USA. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(3):532–541.

Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):244–251.

Salazar JH, Goldstein SD, Yang J, et al. Regionalization of Pediatric Surgery: Trends Already Underway. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1062–1066.

Swan RZ, Niemeyer DJ, Seshadri RM, et al. The impact of regionalization of pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic Cancer in North Carolina since 2004. Am Surg. 2014;80(6):561–566.

Coleman DL. The impact of the lack of health insurance: how should academic medical centers and medical schools respond? Acad Med. 2006;81(8):728–731.

Acknowledgements

Vikrom Dhar and Young Kim contributed equally as co-first authors to this manuscript.

Category 1

Conception and design of study:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Richard S. Hoehn MD, and Shimul A. Shah MD MHCM.

Acquisition of data:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Koffi Wima MS.

Analysis and/or interpretation of data:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Koffi Wima MS, Richard S. Hoehn MD, and Shimul A. Shah MD MHCM.

Category 2

Drafting the manuscript:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD.

Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Koffi Wima MS, Richard S. Hoehn MD, and Shimul A. Shah MD MHCM.

Category 3

Final approval of the version of the manuscript to be published:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Koffi Wima MS, Richard S. Hoehn MD, and Shimul A. Shah MD MHCM.

Category 4

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work:

Vikrom K. Dhar MD, Young Kim MD, Koffi Wima MS, Richard S. Hoehn MD, and Shimul A. Shah MD MHCM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, each author certifies that this material or similar material has not been and will not be submitted to or published in any other publication before its appearance in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati.

Grants and Financial Support

University of Cincinnati Department of Surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dhar, V.K., Kim, Y., Wima, K. et al. The Importance of Safety-Net Hospitals in Emergency General Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 22, 2064–2071 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3885-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3885-8