Abstract

Background

The predictive risk factors of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula (CR-PF) following distal pancreatectomy (DP) remain to be identified.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of a single-institution database of patients undergoing DP, taking into account usual demographic, operative, and pathologic variables and visceral fat area (VFA), total muscle area (TMA), and surface muscle index (SMI) measured on preoperative CT scan. The primary end point was CR-PF. All variables associated with a p value < 0.05 on univariate analysis were included in a logistic regression model for multivariate analysis.

Results

From 2012 to 2016, 208 patients operated by 4 pancreatic surgeons underwent DP including 32 (15%) who developed CR-PF. Risk factors of CR-PF on univariate analysis were: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (p = 0.050), VFA ≥ 92 cm2 (p = 0.006), laparotomy (p = 0.023), main pancreatic duct dilatation (p = 0.035), open passive drainage (versus closed suction drainage) (p = 0.001), and blood loss ≥ 225 ml (p = 0.001). Sarcopenia did not influence the risk of CR-PF (p = 0.076). On multivariate analysis, VFA ≥ 92 cm2 (OR 3.14; IC 95% (1.18–8.31), p = 0.022), blood loss ≥ 225 ml (OR: 2.72; IC 95% (1.06–6.96), p = 0.037), and open passive drainage (OR 3.72; IC 95% (1.40–9.87) p = 0.008) were three independent predictive factors of CR-PF. A CR-PF risk score was developed, predicting a 0% risk of CR-PF when no risk factors were present and a 39% risk when the 3 risk factors were present.

Conclusions

Visceral obesity, blood loss ≥ 225 ml and open passive drainage significantly increase the risk of CR-PF following DP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Distal pancreatectomy (DP) represents approximately 20% of pancreatectomies1 and has a low mortality < 2%2 but a high morbidity, ranging from 23 to 40%.3,4 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is the most frequent complication and occurs in 15 to 60% of patients.3,4,5 Clinically relevant pancreatic fistula (CR-PF) prolongs the hospital stay and can induce life-threatening events including hemorrhage or sepsis6,7 so preventing this complication is a major challenge.

Thus far, the suggested risk factors of CR-PF following DP are intraoperative features including the texture of the pancreatic remnant and the absence of ligation of the main pancreatic duct (MPD).8, 9 Recently, there has been increasing interest in various characteristics of nutritional status and their potential influence on the risk of PF.10 These parameters include body mass index,11 leucocyte count, serum albumin level12,13 as well as morphological criteria indicating visceral obesity14 and sarcopenia.15

Although several studies have incorporated these characteristics to develop predictive scores of the risk of PF following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD),16,17 there are no existing studies evaluating patients who undergo DP. The aim of the present retrospective cohort analysis was to assess the risk factors of CR-PF following DP, including anthropometric factors. We also attempted to develop a simple prognostic score of CR-PF.

Methods

Study Population

All patients who underwent elective DP (distal pancreatectomy and distal splenopancreatectomy) from 2012 to 2016 without an associated extra-pancreatic procedure (except cholecystectomy) for benign or malignant disease were included.

Data Collection

After institutional review board approval (IRB 12–055), standard data were extracted from a prospective database in a single institution that automatically collected various preoperative and intraoperative data retrieved from medical records. Measurements for the evaluation of sarcopenia and visceral adiposity were specifically performed for this study.

Surgical Management

All patients underwent laparoscopic or open DP with or without splenectomy as previously described.18,19,20 Splenectomy was performed in case of distal malignancy or marked inflammatory changes involving the splenic hilum. Pancreatic transection was performed at the splenomesenteric confluence in most cases. DP with splenic preservation included preservation of splenic vessels whenever this was technically and oncologically feasible, otherwise the splenic vessels were resected (Warshaw’s procedure). The diameter of the main pancreatic duct and the texture of the pancreatic parenchyma (soft or hard) at the level of transection were evaluated on imaging and by manual or laparoscopic palpation. The method of pancreatic stump closure was chosen by the operating surgeon, usually by linear stapler in laparoscopic DP and manual suture in open DP. Suture ligation of the MPD was performed whenever possible. The type of abdominal drainage was chosen by the operating surgeon: an open passive drainage (multichannel silicone open drain, Porges-Coloplast™, Humlebæk, Denmark) or a closed suction drainage (three fourth fluted silicon drain, Peters Surgical™, Bobigny, France) was placed near the pancreatic stump. Historically, we exclusively used open passive drainage8 and shifted progressively to closed suction drainage during the study period. No other types of drain were used. Neither fibrin glue nor patches (hemostatic, omental, or ligamentum teres) were used. For all patients, amylase assay in drainage fluid was routinely performed at days 3 and 5, and day 7 when drain was still in place. Drains were removed from postoperative day 5, in the absence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). Postoperative CT scan was routinely performed in patients with POPF to detect collection. Only symptomatic collections (pain, fever, inability to eat) were treated by intervention. Amylase assay was performed routinely for every collection treated by percutaneous drainage or reoperation.

Imaging Analysis

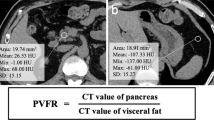

All patients underwent a preoperative unenhanced and contrast-enhanced multiphasic CT scan within 6 weeks after surgery. Attenuation of the pancreas was measured in Hounsfield units (HU) to evaluate parenchymal fat content. Sarcopenia was assessed by semi-automated measurement and manual outlining of the psoas muscle borders at L3 with the attenuation threshold set between − 30 and 110 HU. This provided an automatic calculation of total muscle area (TMA) by excluding vasculature and areas of fatty infiltration. The skeletal muscle index (SMI) was obtained by measuring TMA at L3 with normalization for size (SMI = TMA (cm2)/height2 (m2)). Patients were considered to have sarcopenia when the SMI was below 52.4 cm2/m2 in men and 38.9 cm2/m2 in women.21,22,23,24

The visceral fat area (VFA) was calculated by subtracting the subcutaneous fat area (SFA) from the total fat area (TFA) at L3. Pixel attenuation analysis within the 190–30 HU range was used to outline total and visceral compartments and to calculate the cross-sectional area of each in square centimeter. Visceral obesity has already been defined as a VFA between 100 and 130cm2.14,25 Our group previously showed that VFA > 84 cm2 increased the risk of CR-PF following PD.26 In the present study, we determined cut-off values for risk factors of PF using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis with the optimal value defined by the Youden index.

All measurements were performed using the OsiriX software (Pixmeo™, Geneva, Switzerland) which is a picture archiving and communication system supporting the DICOM standard. Measurements were performed by a surgery resident (CV) and 10% of randomly selected patients underwent a second set of measurements, in a blinded fashion, by a senior radiologist (MR) (Fig. 1).

Postoperative Complications

Postoperative complications that occurred within 90 days after surgery were stratified according to the Dindo–Clavien classification.27 Postoperative PF (POPF) was defined according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF).28 Patients with POPF routinely underwent abdominal imaging to detect collections and adapt drain management. CR-PF included grade B and C POPF according to ISGPF criteria. Post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH)29 and delayed gastric emptying (DGE)30 were defined according to ISGPS criteria.

Statistical Analysis

The primary end point was the development of CR-PF. Quantitative variables were expressed as means (± standard deviation) or medians (range) as appropriate. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages). A Student test or Mann-Whitney U test was used for intergroup comparisons of quantitative variables as appropriate and a chi 2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical data.

To be included in a score, all relevant continuous variables were converted to categorized values. Cut-off values for quantitative variables were determined using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis with optimal values defined by the Youden index. The probability of developing CR-PF was estimated by the multivariate logistic regression model with backward selection. All relevant variables that were identified in univariate analysis with a p value < 0.05 were included in the logistic model. This threshold was voluntarily chosen to limit the number of factors included in the model given the low number of events. The surgeon’s and radiologist’s measurements were compared by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient, and with a Bland and Altman plot.

To build a simple score to predict CR-PF after DP, all factors independently associated with CR-PF on multivariate analysis were given one point. This score was validated by a bootstrap method using N = 2000 bootstrap repetitions, and the confidence interval for the prediction of CR-PF was determined.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R statistical analysis software with the “boot” and “rms” modules.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-three of 231 patients who underwent DP with associated non-gallbladder extra-pancreatic resection (colon, adrenal gland, stomach, liver, or celiac trunk) were excluded. The final population included 208 patients (Table 1), 121 men (58%), mean age 58 years old (range 19–87). The most frequent indications for DP were ductal adenocarcinoma (n = 60; 29%), intraductal papillary and mucinous neoplasms (n = 50; 24%), and neuroendocrine tumors (n = 34; 16%). Patients were mainly ASA I or II (94%). Thirty-nine and 18 patients were active smokers and receiving neoadjuvant treatment, respectively.

Preoperative Imaging Analysis

Results of preoperative imaging are presented in Table 1. The mean VFA for the entire series was 134 cm2 (13–490). Based on the abovementioned SMI thresholds, 156 patients (75%) were sarcopenic, with an equal distribution between men and women.

Measurement of anthropometric and radiological parameters required 5 to 6 min per patient. The intraclass correlation coefficients between the two readers for the TMA, TFA, and SFA were 0.96, 0.99, and 0.99, respectively. The Bland and Altman plot showed a bias (and 95% limits of agreements) of 0.8 (− 24/+ 25] for TMA, − 5.5 (− 71/+ 60) for TFA, and − 15 (− 50/+ 21) for SFA.

Intraoperative Data

DP was performed by four pancreatic surgeons. A laparoscopic approach was used in 110 (53%) patients. Eighty-two patients (39%) underwent splenectomy and 16 (8%) a superior mesenteric or portal vein resection (Table 2). The pancreas was “soft” in 182 (83%) and the MPD was dilated (≥ 3 mm) at the level of transection in 51 (25%) patients. MPD ligation was performed in 119 patients (57%). Closure of the pancreatic stump was performed manually (61%) and by stapler (39%). Blood loss was higher after the open approach than after the laparoscopic approach (blood loss ≥ 225 mL 65 (66%) versus 40 (36%), p < 0.001). Closed suction drainage and open passive drains were used in 92 (44%) and 112 patients (54%), respectively. No drainage was used in four patients (2%). Fifteen (7%) patients required intraoperative transfusion (1 to 5 units). Mean operative time was 187 min (60–255).

Postoperative Course

Sixty-five patients (31%) developed PF (Table 3), including 32 (15%) with CR-PF (grade B = 30 and grade C = 2). Forty-six (22%), including 23 with CR-PF, had fluid collections and 8 patients presented with delayed hemorrhage (4%) including one who developed hemorrhage secondary to CR-PF. The seven other patients (three operated by the laparoscopic and four by open approach, including two receiving therapeutic anticoagulation therapy) bled without CR-PF (two from the pancreatic bed, one from the pancreatic cut surface, two from portal reconstruction, and two from the abdominal wall).

Seventy-nine patients developed major 16 (8%) and minor 63 (30%) complications. The hospital stay was longer in patients with CR-PF (25 vs. 12 days; p < 0.001; (SD 9 vs. 6)). One patient (0.5%) died postoperatively from a stroke. There was a trend towards a higher VFA in the group of patients with CR-PF, (158 vs. 129 cm2, p = 0.054) than in those without CR-PF. A VFA threshold of 92 cm2 was found to maximize the Youden Index, with a sensitivity and specificity of 81 and 45%, respectively, for the occurrence of CR-PF. A threshold of blood loss of 225 ml was determined with a sensitivity and specificity of 81% of 54%, respectively. There were no significant differences in the density of the pancreas (p = 0.271) between patients who did or did not develop CR-PF.

Factors Associated with CR-PF

Patients with CR-PF had a significantly higher BMI (mean 26.0 vs. 24.7 kg/m2, p = 0.026; (SD 4.8 vs. 3.9)). In univariate analysis (Table 4), BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (p = 0.039), VFA ≥ 92 cm2 (p = 0.006), an open approach (p = 0.023), dilatation of the MPD (p = 0.035), intraoperative blood loss ≥ 225 ml (p = 0.001), and use of open passive drainage (p = 0.001) significantly increased the risk of developing CR-PF. The CR-PF rate did not significantly differ in relation to pathological diagnosis, neoadjuvant treatment, preoperative active smoking (Table 1), or operating surgeon (Table 2). Particularly, the rates of CR-PF observed after DP performed by surgeons A, B, C, and D were 16% (13/83), 20% (14/70), 13% (5/39), and 0% (0/16), respectively (p = 0.235, not significant). The risk of CR-PF was not significantly influenced by the soft consistency of the parenchyma and the elective ligation of the main duct (p = 0.072 and p = 0.068, respectively).

There was a trend towards a lower rate of CR-PF in patients with sarcopenia (p = 0.076) and when a linear stapler was used for closure of the pancreatic stump (p = 0.079). Eighty patients (38%) had both visceral obesity and sarcopenia, including 15 (19%) who developed CR-PF compared to 4 (5%) in non-obese patients with sarcopenia (p = 0.009).

On multivariate analysis, VFA ≥ 92 cm2 (OR 3.14; IC 95% (1.18–8.31), p = 0.022), blood loss ≥ 225 ml (OR 2.72; IC 95% (1.06–6.96), p = 0.037), and open passive drainage (OR 3.72; IC 95% (1.40–9.87) p = 0.008) were three independent predictive factors of CR-PF (Table 4).

We developed a simple score from 0 to 3 by giving 1 point to visceral obesity, intraoperative blood loss > 225 ml, and open passive drainage. The number of patients who received one point due to visceral obesity, intraoperative blood loss > 225 ml, and open passive drainage were 123, 105, and 112, respectively. Overall, 25 (12%), 71 (34%), 63 (30%), and 49 (24%) patients had a score of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The rate of CR-PF was 0, 8, 11, and 39% for a score of 0 to 3, respectively (p < 0.001). Because the CR-PF rates in patients with scores of 1 and 2 were close, these patients were merged to create a three-scale score from 0 to 2. Overall, 25(12%), 134 (64%), and 49 (24%) patients had a score of 0, 1–2, and 3, with rates of CR-PF of 0, 10, and 39%, respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 5). This score predicted CR-PF with an area under the ROC curve of 0.741 (95% CI 0.647–0.834). After bootstrapping, the mean AUC for 10,000 tests in the original regression model was 0.73 leading to an optimism in the apparent performance of 0.011. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test did not show any deviation between the model and the observed rates (p = 0.882). An increased score was associated with a prolonged hospital stay (p < 0.001). The rate of patients who stayed in the ICU was 0, 11, and 12%, respectively.

Discussion

Visceral obesity, high intraoperative blood loss, and open passive drainage were three independent risks factors of CR-PF in this series of DP in a tertiary-referral center. On the other hand, sarcopenia was not associated with an increased risk of CR-PF. We chose CR-PF as a primary end point because the ISGPF recently confirmed that grade A PF does not influence the postoperative course, and re-categorized “grade A postoperative PF” as “biochemical leaks,” so they are no longer considered “true” PF.31 We also developed a score that accurately predicted CR-PF and identified patients with no risk, low risk, and a high risk of this complication and was also helpful in predicting the overall length of hospital stay. These results could improve perioperative management of DP and help to tailor preventive measures depending on the predicted risk of CR-PF.

Although the predictive risk factors of PF have been extensively studied in PD,16,17,26,32,33,34 only a few predictive risk factors have been suggested for PF following DP, including BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2,9 the absence of ligation of the MPD,8 division of the pancreas at the body level,8 and blood loss > 150 ml.35 Previous studies have also suggested that certain morphometric parameters were risk factors of PF following DP.10,14,36,37 To date, there are very few data on PF following DP even though this is the most frequent complication.28 Some of the risk factors of CR-PF following DP that were identified in this study on univariate analysis have been reported in prior studies: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m29 or dilated MPD.8,38,39 BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was not associated with a higher risk of CR-PF in the present study. It could be due to the low number of obese patients in our population (Table 1) and the relatively low prevalence of obesity (around 15%) in the general population in France (https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Obesity-Update-2017.pdf). One study recently analyzed imaging features predictive of PF after DP10 and identified margin thickness, but not density of the pancreas or fat infiltration, as relevant findings. However, other morphometric parameters and drainage modalities were not studied.

The first independent predictive factor of CR-PF identified in the present study was visceral obesity assessed on CT, which also favors morbidity after colorectal surgery,25 liver transplantation,40 and pancreatic surgery. We have previously shown that VFA > 84 cm2 increased the risk of CR-PF following PD.26 A threshold of 100 cm2 has been also proposed in this same setting.41 The present study identified a slightly lower threshold (≥ 92cm2), and more than 80% of the patients who developed CR-PF had a VFA above this threshold. Measurement of VFA is easy, does not require radiological skill, and uses software which is mainly a picture archiving and communication system so the cost can be depreciated by daily use.

To our knowledge, the influence of sarcopenia on morbidity following DP has never been evaluated. Sarcopenia is frequent in patients with pancreatic disease14 and was present in 75% of the patients in the present study. Sarcopenia did not increase the risk of PF after DP in the present study, unlike in previous reports concerning PD.15,42 Indeed, the influence of sarcopenia on the early postoperative course of pancreatectomies has been studied in the literature but the results of DP were always mixed with that of PD, the latter being always the most frequent procedure, so specific results of DP were not available.

Closed suction drainage was also associated on multivariate analysis with a significant decrease in the rate of CR-PF compared to open passive multichannel open drainage. To our knowledge, this is the first time this result has been reported. Although the need for abdominal drainage following PD is controversial,43,44 this cannot be transposed to DP since the former includes three anastomoses. Historically, we exclusively used open passive drainage after DP,8thus explaining that this modality was used in the present study. Modalities of abdominal drainage following DP are still debated. One recent multicenter randomized controlled trial compared the postoperative course of DP with and without drainage and did not find any significant difference in the rates of CR-PF and severe complications between both arms. The only difference was a higher rate of abdominal collections in the non-drainage arm.45 In that study, closed suction drains were used in most patients who received drainage but the drainage policy was not consistent. Another retrospective multinational study of 2026 patients reported that intraoperative drainage was associated with a greater rate of fistulas (OR 2.09, p < 0.001) but also reduced severity of fistulas,46 suggesting that drainage cannot be routinely excluded after DP but should only be used in a subset of patients.

The third independent predictive risk factor of CR-PF after DP that was identified in our study was blood loss ≥ 225 ml. Malleo and al. have already reported that patients with blood loss ≥ 150 mL were more likely to develop major postoperative complications after laparoscopic DP.35 Intraoperative blood loss is clearly a risk factor of CR-PF after PD and it was therefore included a prognostic score of CR-PF.16 These thresholds ranging from 150 to 225 mL represent very limited blood loss. Although intraoperative blood loss can be related to several factors including the surgical approach, tumor stage, or local inflammation, intraoperative techniques designed to minimize blood loss may help to reduce the risk of CR-PF.

Because multivariate analysis identified three independent factors with a cumulative effect, we developed a simple scoring system with an accurate predictive value. The respective weight of each of these 3 factors was equivalent since each was present in approximately 110 patients. Since patients with one or two risk factors were exposed to an equivalent risk of CR-PF, we simplified this score by merging patients with scores of 1 and 2. Overall, the risk of CR-PF in patients with a score of 0, 1–2, and 3 were 0, 10, and 39%, respectively (p < 0.001). The aim of a predictive score of PF is to tailor preventive measures and perioperative management. The intraoperative strategy should be adapted to include covering of the pancreatic stump with ligamentum teres47 in patients at high risk of PF following DP, including those with visceral obesity, as well as wrapping the cut surface of the pancreas with polyglycolic acid mesh,5 or perioperative use of pasireotide which seems to effectively prevent CR-PF.48 Closure of the pancreatic stump by either manual sutures or stapler provides similar results.49 Covering of the pancreatic stump with ligamentum teres and routine use of closed suction drain are the most easily available and less costly measures to implement during both open and laparoscopic DP. However, it is still unclear whether patients with visceral obesity and benign disease should lose weight before surgery to decrease the risk of CR-PF.

The present study has some limitations. First, it was performed in a single institution and the number of patients is fairly small. Second, the design is partially retrospective since anthropometric data were not collected prospectively. Thirdly, some uncontrolled confounding factors were likely omitted, particularly regarding operative approach and drainage type which were chosen at the discretion of the operating surgeon, and blood loss which was influenced by the operative approach and probably by the underlying disease. Lastly, we did not analyze the influence of parenchyma alterations at the level of pancreatic transection on the risk of CR-PF since this should have needed to review all histological slices by a pathologist blinded to the postoperative course.

Conclusions

Visceral obesity, open passive drainage, and blood loss ≥ 225 ml were associated with an increased risk of postoperative CR-PF following DP. Sarcopenia does not seem to influence this risk. Thus, intraoperative blood loss should be limited as much as possible and routine use of a closed suction drainage should be emphasized. Preoperative assessment of VFA should be performed because patients with visceral obesity have an increased risk of CR-PF, which could justify additional preventive measures.

Abbreviations

- CR-PF:

-

Clinically relevant pancreatic fistula

- DP:

-

Distal pancreatectomy

- PD:

-

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary and mucinous neoplasm

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiology

- SFA:

-

Subcutaneous fat area

- VFA:

-

Visceral fat area

- TFA:

-

Total fat area

- TMA:

-

Total muscle area

- SMI:

-

Surface Muscle Index

References

Bruns H, Rahbari NN, Löffler T, Diener MK, Seiler CM, Glanemann M, Butturini G, Schuhmacher C, Rossion I, Büchler MW, Junghans T. Perioperative management in distal pancreatectomy: results of a survey in 23 European participating centers of the DISPACT trial and a review of literature. Trials. 2009;10:58.

Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693–698.

Pedrazzoli S, Liessi G, Pasquali C, Ragazzi R, Berselli M, Sperti C. Postoperative pancreatic fistulas: preventing severe complications and reducing reoperation and mortality rate. Ann Surg. 2009;249:97–104.

Casadei R, Ricci C, Taffurelli G, D'Ambra M, Pacilio CA, Ingaldi C, Minni F. Are there preoperative factors related to a “soft pancreas” and are they predictive of pancreatic fistulas after pancreatic resection? Surg Today. 2015;45:708–714.

Jang J-Y, Shin YC, Han Y, Park JS, Han HS, Hwang HK, Yoon DS, Kim JK, Yoon YS, Hwang DW, Kang CM, Lee WJ, Heo JS, Kang MJ, Chang YR, Chang J, Jung W, Kim SW. Effect of Polyglycolic Acid Mesh for Prevention of Pancreatic Fistula Following Distal Pancreatectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2017;152:150–155..

Knaebel HP, Diener MK, Wente MN, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of technique for closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:539–546.

Reeh M, Nentwich MF, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, Gebauer F, Tachezy M, Izbicki JR, Bockhorn M. High surgical morbidity following distal pancreatectomy: still an unsolved problem. World J Surg. 2011;35:1110–1117.

Pannegeon V, Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Vullierme MP, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J. Pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: predictive risk factors and value of conservative treatment. Arch Surg 2006;141:1071–1076.

Sledzianowski JF, Duffas JP, Muscari F, Suc B, Fourtanier F. Risk factors for mortality and intra-abdominal morbidity after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:180–185.

Jutric Z, Johnston WC, Grendar J, Haykin L, Mathews C, Harmon LK, Shen J, Hahn HP, Coy DL, Cassera MA, Helton WS, Rocha FG, Wolf RF, Hansen PD, Hammill CW, Alseidi AA, Newell PH. Preoperative computed tomography scan to predict pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy using gland and tumor characteristics. Am J Surg. 2016;211:871–876.

Chen Y-T, Deng Q, Che X, Zhang JW, Chen YH, Zhao DB, Tian YT, Zhang YW, Wang CF. Impact of body mass index on complications following pancreatectomy: Ten-year experience at National Cancer Center in China. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015;21:7218–7224.

Kang J, Park JS, Yoon DS, Kim WJ, Chung HY, Lee SM, Chang N. A Study on the Dietary Intake and the Nutritional Status among the Pancreatic Cancer Surgical Patients. Clin Nutr Res. 2016;5:279–289.

Kanda M, Fujii T, Kodera Y, Nagai S, Takeda S, Nakao A. Nutritional predictors of postoperative outcome in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:268–274.

Pecorelli N, Carrara G, De Cobelli F, Cristel G, Damascelli A, Balzano G, Beretta L, Braga M. Effect of sarcopenia and visceral obesity on mortality and pancreatic fistula following pancreatic cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103:434–442.

Joglekar S, Asghar A, Mott SL, Johnson BE, Button AM, Clark E, Mezhir JJ. Sarcopenia Is an Independent Predictor of Complications Following Pancreatectomy for Adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:771–775.

Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM Jr. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:1–14.

Roberts KJ, Sutcliffe RP, Marudanayagam R, Hodson J, Isaac J, Muiesan P, Navarro A, Patel K, Jah A, Napetti S, Adair A, Lazaridis S, Prachalias A, Shingler G, Al-Sarireh B, Storey R, Smith AM, Shah N, Fusai G, Ahmed J, Abu Hilal M, Mirza DF.. Scoring System to Predict Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A UK Multicenter Study. Ann Surg 2015;261:1191–7. .

Dokmak S, Fteriche FS, Aussilhou B, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, Cros J, Vullierme MP, Khoy Ear L, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. The largest European single-center experience: 300 laparoscopic pancreatic resections. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:226–234.

Shi N, Liu S-L, Li Y-T, You L, Dai MH, Zhao YP. Splenic Preservation Versus Splenectomy During Distal Pancreatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:365–374.

Fernández-Cruz L, Orduña D, Cesar-Borges G, López-Boado MA. Distal pancreatectomy: en-bloc splenectomy vs spleen-preserving pancreatectomy. HPB. 2005;7:93–98.

Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley JE, Newman AB, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, Bauer J, Breuille D, Cederholm T, Chandler J, De Meynard C, Donini L, Harris T, Kannt A, Keime Guibert F, Onder G, Papanicolaou D, Rolland Y, Rooks D, Sieber C, Souhami E, Verlaan S, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: An Undiagnosed Condition in Older Adults. Current Consensus Definition: Prevalence, Etiology, and Consequences. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:249–256.

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, Baracos VE. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629–635.

Mourtzakis M, Prado CMM, Lieffers JR, Reiman T, McCargar LJ, Baracos VE. A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008;33:997–1006.

Voron T, Tselikas L, Pietrasz D, Pigneur F, Laurent A, Compagnon P, Salloum C, Luciani A, Azoulay D. Sarcopenia Impacts on Short- and Long-term Results of Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1173–1183.

Cakir H, Heus C, van der Ploeg TJ, Houdijk APJ. Visceral obesity determined by CT scan and outcomes after colorectal surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:875–882.

Tranchart H, Gaujoux S, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Dokmak S, Levy P, Couvelard A, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Preoperative CT scan helps to predict severe pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2012;256:136–45.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M; Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138(1):8–13.

Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–25.

Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761–768.

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017; 161:584–591.

Braga M, Capretti G, Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Doglioni C, Ariotti R, Di Carlo V. A prognostic score to predict major complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254:702–707.

Wellner UF, Kayser G, Lapshyn H, Sick O, Makowiec F, Höppner J, Hopt UT, Keck T. A simple scoring system based on clinical factors related to pancreatic texture predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula preoperatively. HPB. 2010;12:696–702.

Shubert CR, Wagie AE, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Que FG, Reid Lombardo KM, Truty MJ, Smoot RL, Kendrick ML. Clinical Risk Score to Predict Pancreatic Fistula after Pancreatoduodenectomy: Independent External Validation for Open and Laparoscopic Approaches. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(3):689–698.

Malleo G, Salvia R, Mascetta G, Esposito A, Landoni L, Casetti L, Maggino L, Bassi C, Butturini G. Assessment of a complication risk score and study of complication profile in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:2009–2015.

Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, Gallagher D, St-Onge MP, Albu J, Heymsfield SB, Heshka S. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;97:2333–2338.

Arai T, Kobayashi A, Yokoyama T, Ohya A, Fujinaga Y, Shimizu A, Motoyama H, Furusawa N, Sakai H, Uehara T, Kadoya M, Miyagawa S. Signal intensity of the pancreas on magnetic resonance imaging: Prediction of postoperative pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy using a triple-row stapler. Pancreatology 2015;15:380–386.

Sugimoto M, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Takahashi S, Kinoshita T, Shibasaki H, Nomura S, Konishi M, Kaneko H. Risk factor analysis and prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy with stapler use. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:538–544.

Sahakyan MA, Røsok BI, Kazaryan AM, Barkhatov L, Lai X, Kleive D, Ignjatovic D, Labori KJ, Edwin B. Impact of obesity on surgical outcomes of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: A Norwegian single-center study. Surgery. 2016;160:1271–1278.

Terjimanian MN, Harbaugh CM, Hussain A, Olugbade KO Jr, Waits SA, Wang SC, Sonnenday CJ, Englesbe MJ. Abdominal adiposity, body composition and survival after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:289–294.

Park CM, Park JS, Cho ES, Kim JK, Yu JS, Yoon DS. The effect of visceral fat mass on pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Investig Surg 2012;25:169–173.

Nishida Y, Kato Y, Kudo M, Aizawa H, Okubo S, Takahashi D, Nakayama Y, Kitaguchi K, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, Konishi M. Preoperative Sarcopenia Strongly Influences the Risk of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula Formation After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:1586–1594.

Van Buren G, Fisher WE. Pancreaticoduodenectomy Without Drains: Interpretation of the Evidence. Ann Surg. 2016 ;263:e20–1.

Witzigmann H, Diener MK, Kienkötter S, Rossion I, Bruckner T, Bärbel Werner, Pridöhl O, Radulova-Mauersberger O, Lauer H, Knebel P, Ulrich A, Strobel O, Hackert T, Büchler MW. No Need for Routine Drainage After Pancreatic Head Resection: The Dual-Center, Randomized, Controlled PANDRA Trial. Ann Surg. 2016;264:528–537.

Van Buren G, Bloomston M, Schmidt CR, Behrman SW, Zyromski NJ, Ball CG, Morgan KA, Hughes SJ, Karanicolas PJ, Allendorf JD, Vollmer CM Jr, Ly Q, Brown KM, Velanovich V, Winter JM, McElhany AL, Muscarella P II, Schmidt CM, House MG, Dixon E, Dillhoff ME, Trevino JG, Hallet J, Coburn NSG, Nakeeb A, Behrns KE, Sasson AR, Ceppa EP, Abdel-Misih SRZ, Riall TS, Silberfein EJ, Ellison EC, Adams DB, Hsu C, Tran Cao HS, Mohammed S, Villafañe-Ferriol N, Barakat O, Massarweh NN, Chai C, Mendez-Reyes JE, Fang A, Jo E, Mo Q, Fisher WE. A Prospective Randomized Multicenter Trial of Distal Pancreatectomy With and Without Routine Intraperitoneal Drainage. Ann Surg. 2017;266:421–431.

Ecker BL, McMillan MT, Allegrini V, Bassi C, Beane JD, Beckman RM, Behrman SW, Dickson EJ, Callery MP, Christein JD, Drebin JA, Hollis RH, House MG, Jamieson NB, Javed AA, Kent TS, Kluger MD, Kowalsky SJ, Maggino L, Malleo G, Valero V 3rd, Velu LKP, Watkins AA, Wolfgang CL, Zureikat AH, Vollmer CM Jr. Risk factors and mitigation strategies for pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Analysis of 2026 resections from the international multi-institutional Distal Pancreatectomy Study Group. Ann Surg. 2017 Aug 29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002491.

Hassenpflug M, Hinz U, Strobel O, Volpert J, Knebel P, Diener MK, Doerr-Harim C, Werner J, Hackert T, Büchler MW. Teres Ligament Patch Reduces Relevant Morbidity After Distal Pancreatectomy (the DISCOVER Randomized Controlled Trial). Ann Surg 2016;264:723–730

Allen PJ, Gönen M, Brennan MF, Bucknor AA, Robinson LM, Pappas MM, Carlucci KE, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Kingham TP, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR. Pasireotide for postoperative pancreatic fistula. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2014–2022.

Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, Tomazic A, Bruns CJ, Busch OR, Farkas S, Belyaev O, Neoptolemos JP, Halloran C, Keck T, Niedergethmann M, Gellert K, Witzigmann H, Kollmar O, Langer P, Steger U, Neudecker J, Berrevoet F, Ganzera S, Heiss MM, Luntz SP, Bruckner T, Kieser M, Büchler MW. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2011;377:1514–1522.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Charles Vanbrugghe: Conception of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Maxime Ronot: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

François Cauchy: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Christian Hobeika: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Safi Dokmak:Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Béatrice Aussilhou: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Emilia RAGOT: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Sébastien GAUJOUX: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Olivier SOUBRANE: Conception or design of the work, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Philippe LEVY: Acquisition and interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Alain SAUVANET: Conception of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Oral Presentation: European Pancreatic Club, Budapest (Hungary), 29th June 2017

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vanbrugghe, C., Ronot, M., Cauchy, F. et al. Visceral Obesity and Open Passive Drainage Increase the Risk of Pancreatic Fistula Following Distal Pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 23, 1414–1424 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3878-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3878-7