Abstract

Background

Temporary loop ileostomy is a routine procedure to reduce the morbidity of restorative proctocolectomy. However, morbidity of ileostomy closure could reduce the benefit of this concept. The objective of this systematic review was to assess the risks of ileostomy closure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis.

Materials and Methods

Publications in English or German language reporting morbidity of ileostomy closure after restorative proctocolectomy were identified by Medline search. Two hundred thirty-two publications were screened, 143 were assessed in full-text, and finally 26 studies (reporting 2146 ileostomy closures) fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Weighted means for overall morbidity and mortality of ileostomy closure, rate of redo operations, anastomotic dehiscence, bowel obstruction, wound infection, and late complications were calculated.

Results

Overall morbidity of ileostomy closure was 16.5 %, there was no mortality. Redo operations for complications were necessary in 3.0 %. Anastomotic dehiscence occurred in 2.0 %. Postoperative bowel obstruction developed in 7.6 %, with 2.9 % of patients requiring laparotomy for this complication. Wound infection rate was 4.0 %. Hernia or bowel obstruction as late complications developed in 1.9 and 9.4 %, respectively.

Conclusion

The considerable morbidity of ileostomy reversal reduces the overall benefit of temporary fecal diversion. However, ileostomy creation is still recommended, as it effectively reduces the risk of pouch-related septic complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is the surgical standard therapy for patients with refractory ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis who require proctocolectomy.1 Despite the evolving surgical techniques, including double stapling anastomosis and omission of routine proctomucosectomy, pouch-related septic complications remain feared consequences of pouch-anal anastomosis. They occur in about 10 % of restorative proctocolectomies.2 – 4 Pouch-related septic complications have substantial negative impact on pouch function and pouch failure rate,5 – 9 and they account for more than half of all pouch failures.9 Temporary fecal diversion by loop-ileostomy is a very effective strategy to reduce these complications. In her meta-analysis, Weston-Petrides 2 calculated a risk of anastomotic dehiscence of 9.4 % without covering ileostomy versus 4.3 % with covering ileostomy (OR = 2.37, p = 0.002).

However, in most publications (including the abovementioned meta-analysis) morbidity of ileostomy reversal is not taken into account. This morbidity is generally underestimated and several studies reported morbidity rates of more than 10 %.10 – 12 In our own series of two-stage restorative proctocolectomies, the morbidity surrounding ileostomy closure of 14.8 % substantially reduced the advantages of loop ileostomy.10 In some series, the risks of ileostomy creation and reversal even outweighed its advantages, leading to the recommendation of single-stage procedures in selected patients.13 – 15

The aim of this systematic review was to clarify the risks of ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy in order to allow a critical assessment of advantages and risks of fecal diversion.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and checklist.16 The A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist was used as additional reference to ensure methodological quality.17 Objective of the review and specific outcomes of interest (see below) were defined before starting the literature search.

Eligibility Criteria

All studies reporting outcomes of ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis were considered. Language restrictions were made to English and German language.

Inclusion Criteria (All Must be Fulfilled)

-

1.

Study includes patients with ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy.

-

2.

Study reports at least one of the defined outcome criteria (see below).

-

3.

Sufficient data extraction (calculation of exact number of affected patients) is possible.

Exclusion Criteria (None is Allowed)

-

1.

Study does not include patients with ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy.

-

2.

Study does not report any of the defined outcome criteria.

-

3.

Double publication (in this case, the newest publication is included in the analysis).

-

4.

Sufficient data extraction is not possible (e.g., study reporting pooled outcomes of ileostomy reversals both after rectal resection for cancer and after proctocolectomy, not allowing to calculate the outcome criteria for proctocolectomy separately).

-

5.

Case reports.

-

6.

Case series reporting exclusively patients developing complications (morbidity 100 %).

Literature Search

The literature search was performed in Medline using PubMed. The latest search date was October 28, 2011. The following search string was used: (Loop Ileostomy OR Defunctioning Ileostomy OR Ileostomy) AND (Reversal OR Closure) AND (Complications OR Complication OR Morbidity) AND (Ulcerative Colitis OR FAP OR Proctocolectomy OR Familial Adenomatous Polyposis).

This search led to 223 results. References of all papers were cross-checked, leading to the identification of further nine publications. The flow diagram of study selection is depicted in Fig. 1.

The assessment of all publications was independently performed by two reviewers (RM and WS); in any case of different assessment a consensus was reached by discussion with all authors. Screening of abstracts led to the exclusion of 89 publications, the full text of the remaining studies was carefully reviewed (n = 143). After exclusion of double publications and assessment of eligibility and exclusion criteria, 26 publications10 – 12 , 15 , 18 – 39 were included in the data analysis. The study selection and review procedure including the reason for exclusion for each study was protocolled.

Outcome Criteria

-

1.

Demographic data on study populations, such as age, gender, and underlying disease (ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis).

-

2.

Surgical details of ileostomy reversal (e.g., type of anastomosis, need for laparotomy, and length of hospital stay).

-

3.

Morbidity of ileostomy reversal, including early complications (such as redo operation, anastomotic dehiscence at the stoma closure site, postoperative bowel obstruction, and wound infection) and late complications (stoma site hernia and bowel obstruction later than 30 days after ileostomy reversal).

-

4.

Mortality of ileostomy reversal.

Data Analysis

Raw data (numbers) of affected patients and patients at risk were calculated from the included studies for the respective outcome criterion. If only percentages were given, raw numbers were calculated whenever possible. Weighted means (percentages) of all studies reporting the respective outcome criterion were calculated dividing the number of patients affected by the number of patients at risk. A funnel plot was used as visual aid to identify a possible publication bias or systematic heterogeneity of the included studies.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies and Study Populations

After the review process, 26 publications were included in the data analysis9 – 11 , 14 , 17 – 38 (Table 1). Publication years ranged from 1985 to 2011. Most studies were retrospective series (n = 18), whereas eight studies declared prospective data collection during follow-up, e.g., by means of a prospectively maintained database.11 , 18 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 34 However, there were no controlled prospective randomized trials.

Two thousand seven hundred twenty-four patients were reported in these studies. However, as several studies were not exclusively reporting patients with restorative proctocolectomy, 2429 patients with ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis undergoing restorative proctocolectomy were identified. About 91.1 % of these patients (n = 2212) had a temporary ileostomy while the remainder had a one stage procedure. A temporary ileostomy was created during a two-stage proctocolectomy in 82.5 %, during a three-stage procedure in 17.5 %. As some patients did not undergo planned ileostomy reversal, some 2146 ileostomy reversal procedures remained for inclusion in the analysis of morbidity.

The total study population consisted of 56.7 % men and 43.3 % women, with a mean age of 35.5 years. The indication for restorative proctocolectomy was ulcerative colitis in 94.3 % and familial adenomatous polyposis in 5.7 %, respectively. Immunosuppressive medication was present at the time of proctocolectomy in 61.7 % of patients, as reported in seven studies.10 – 12 , 15 , 18 , 25 , 33 Although it can be presumed that steroids and immunosuppressive medication were completely weaned before ileostomy reversal in virtually all patients, most authors did not explicitly comment on this topic.

Details of Ileostomy Reversal

Fifteen studies provided data on the time interval between proctocolectomy and ileostomy reversal.11 , 18 – 21 , 25 – 27 , 30 – 33 , 35 – 37 The weighted mean duration of fecal diversion was 92 days; the range of reported means was 61–128 days. All 13 authors who commented on this topic performed routine pouchoscopy and pouchography before ileostomy reversal in 100 % of patients.10 , 11 , 23 , 25 – 28 , 30 – 32 , 35 , 36 , 38

Ileostomy reversal technique, as reported in eight publications,10 , 20 , 21 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 32 was hand-sewn anastomosis in 56.6 % and stapler anastomosis in 43.4 %. A laparotomy was needed for stoma reversal in 8.0 % (as reported in six publications).20 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 35 , 38

Morbidity of Ileostomy Reversal: Early Complications

Morbidity of ileostomy reversal including different categories of early complications is summarized in Table 2. Overall morbidity was 16.5 %; there was no mortality. Postoperative complications mandated redo surgery in 3.0 % of patients. Anastomotic dehiscence at the stoma closure site occurred in 2.0 %, postoperative bowel obstruction in 7.6 %. Most cases of postoperative bowel obstruction could be managed conservatively; however, 2.9 % required laparotomy for postoperative bowel obstruction. The rate of wound infection after ileostomy reversal was 4.0 %.

Despite the routine endoscopy and pouchography before ileostomy reversal, pouch-related septic complications (including dehiscence of the pouch-anal anastomosis, pouch fistula, and pelvic abscess) developed early after stoma reversal in 1.9 % (as reported in eight studies).10 , 26 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 37 – 39

Morbidity of Ileostomy Reversal: Late Complications

Stoma site hernias and bowel obstruction (developing later than 30 days after ileostomy reversal) were studied as late complications (Table 3); they occurred in 1.9 and 9.4 %, respectively.

In 3.5 % of patients, the initial diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was revised to Crohn′s disease during follow-up (as reported in nine studies).19 , 22 , 27 – 29 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 39 Although this cannot be considered as “surgical” late complication, Crohn′s disease led to pouch failure at a later stage in 2.4 % of patients in these studies.

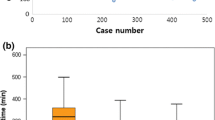

Assessment of Possible Publication Bias: Funnel Plot

As a visual aid to detect a possible publication bias or systematic heterogeneity of the studies, a funnel plot of effect size (reported morbidity of ileostomy reversal) against study size (number of ileostomy reversals included in the respective study) was created, Fig. 2. The funnel plot shows a roughly symmetric inverted funnel shape which makes publication bias unlikely. Reported morbidity values of larger studies are close to the average morbidity (16.5 %), whereas smaller studies report lower and higher values without systematic preference.

Sensitivity Analysis

Since the effect sizes may differ according to the size of the included studies, a sensitivity analysis was performed including only studies reporting on more than 50 ileostomy reversal procedures, thus excluding extreme values of smaller studies (see funnel plot, Fig. 2). In this subset of large studies, overall morbidity of ileostomy reversal was 17.0 % (as reported in six studies10 , 11 , 15 , 20 , 28 , 35), redo surgery was necessary in 2.3 % (as reported in three studies10 , 30 , 34), anastomotic dehiscence occurred in 1.7 % (as reported in eight studies10 , 15 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 28 , 30 , 35), postoperative bowel obstruction in 7.1 % (as reported in five studies10 , 18 , 20 , 28 , 35). These parameters showed no systematic trend towards higher or lower values compared to the complete study population.

Discussion

This systematic review of ileostomy reversals after proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis reveals a considerable morbidity of 16.5 % associated with this procedure. Redo surgery for complications was necessary in 3.0 % of patients, and postoperative bowel obstruction was the main determinant of early postoperative morbidity, occurring in 7.6 %.

Most surgeons prefer to create a temporary loop ileostomy during restorative proctocolectomy,40 and this policy is supported by several studies demonstrating the reduction of severe complications, especially pouch-related septic complications.10 , 41 – 45 However, some publications suggested that one-stage procedures can be considered for selected low-risk patients.46 – 49 This issue has been elucidated by a meta-analysis of studies on the use or omission of a diverting ileostomy.2 The risk of anastomotic dehiscence was significantly reduced; however, a difference for pouch-related sepsis was only found if exclusively high-quality studies were included in the analysis. The advantage of fecal diversion was challenged by a higher rate of anastomotic strictures in the ileostomy group (15.3 versus 5.1 % without stoma; p = 0.045). Importantly, the risks of scheduled ileostomy reversal were not included in the overall morbidity.2

The risks of ileostomy closure tend to be underestimated. Usually, it is regarded as low-risk standard procedure; in many centers, this is a typical operation to be done by trainees under the supervision of an experienced senior surgeon. However, details on the degree of experience of the operating team are not available from the studies included in this review. Only few publications discussing the potential benefits of a covering ileostomy take the morbidity of stoma reversal into account. For restorative proctocolectomy, the cumulative morbidity of ileostomy creation and reversal often outweighed the morbidity reduction achieved for the proctocolectomy.10 , 13 – 15 The systematic review of ileostomy reversals by Chow 50 was one of the first reports that brought into mind the concerning complication rates of about 17 %. Recently, several publications on morbidity of ileostomy reversal report rates of 20–40 %,51 – 56 possibly reflecting an increasing awareness and an honest reporting of this issue. These values are higher than those found in the actual review and in that of Chow, 50 so it seems possible that there is a certain publication bias (underreporting) in older studies. Interestingly, the interpretation of these complication rates can differ completely; while many authors are concerned about the rather high complication rates, other authors even propose performing ileostomy reversal as day case surgery.57 , 58

Previous reports on the morbidity of ileostomy reversal, including the abovementioned systematic review by Chow, 50 do not differentiate the underlying primary procedures that led to ileostomy creation; they rather provide pooled data on various indications, such as anterior rectal resection, colonic resection, or restorative proctocolectomy. A priori, we hypothesized that patients after restorative proctocolectomy might have a different risk profile compared to patients after rectal or colonic resection. From the technical point of view, after restorative proctocolectomy, the ileostomy site usually is located more proximal in the ileum. Furthermore, the lack of the ileocecal valve and of residual colon could make a difference especially for postoperative bowel obstruction. Therefore, we exclusively included patients undergoing ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy in our present analysis.

However, the main outcome measures (overall morbidity, redo operations, and postoperative bowel obstruction) found in our study were quite similar to those reported by Chow 50 indicating that the underlying type of surgery does not significantly influence complication rates. Nevertheless, there are two important novel aspects in our study that are only relevant after restorative proctocolectomy. First, we could show that 1.9 % of patients develop pouch-related septic complications after ileostomy reversal. This indicates that preoperative endoscopy and pouchography cannot completely rule out unapparent fistulas and leakages that lead to these complications once the fecal stream is reestablished. Second, 3.5 % of patients supposed to have ulcerative colitis will later be diagnosed as having Crohn′s disease. This is important, as the pouch failure rate is as high as 20 % at 10 years after proctocolectomy in patients with Crohn′s disease.4

The high morbidity of ileostomy reversal leads to the question if the policy of covering ileostomy should be modified. On one hand, adding the morbidities of proctocolectomy and ileostomy reversal basically leads to comparable overall morbidity rates for one- and two-stage proctocolectomy procedures, and ileostomy creation means one additional surgical procedure and a longer total hospital stay for the patient. On the other hand, pouch-related septic complications are significantly reduced by ileostomy,2 even if the few cases developing pouch-related septic complications after stoma reversal are taken into account. These severe complications have the greatest impact on pouch function and failure rate, and they are difficult to manage.5 – 9 , 59 Taken together, the reduction of pouch-related septic complications is achieved by accepting other complications, like bowel obstruction, wound infections, and others. Because of the extraordinary impact of pouch-related septic complications on pouch function, pouch failure, and postoperative quality of life, routine creation of a covering ileostomy still is advocated. However, the considerable morbidity of ileostomy reversal has to be recognized, especially when informing the patient about indication and risks of a covering ileostomy.

The reported work-up before ileostomy reversal was basically similar in all studies; all authors performed endoscopy and pouchography; the mean time interval between fecal diversion and ileostomy reversal was 3 months. However, as mentioned above, routine pouchography did not prevent pouch-related septic complications after ileostomy reversal. Selvaggi 60 recently showed that negative pouchography does not exclude future complications. In addition, all anomalies detected by pouchography were already suspected clinically. This led to the conclusion that routine pouchography may be safely omitted before ileostomy closure.60

Postoperative bowel obstruction was the main determinant of early postoperative morbidity after ileostomy reversal, and strategies to reduce this type of complication are necessary. The recent HASTA trial61 showed similar rates of postoperative bowel obstruction for both hand-sewn and stapler anastomosis, so there is no recommendation on either technique in this respect. Laparoscopic surgery might improve the situation, as a recent report demonstrated that ileostomy reversal after laparoscopic surgery was associated with a significantly lower rate of overall complications compared to previous open surgery.62 Bowel obstruction was the most common complication in both groups; however, due to small numbers of complications, the difference of bowel obstruction rate did not reach significance. Royds 63 performed a randomized clinical trial comparing standard ileostomy reversal with and without consecutive laparoscopy allowing the diagnostic assessment of the peritoneal cavity. If adhesions were present, these were divided completely during laparoscopy. Additional laparoscopy was associated with shorter hospital stay, faster return to normal bowel function, lower overall morbidity, and reduced costs.

But even if the rate of early postoperative bowel obstruction can be reduced, bowel obstruction at a later time point remains a problem. At 1 year after ileostomy reversal, the cumulative incidence of bowel obstruction is about 15.0 %, and laparoscopic approach of the previous restorative proctocolectomy does not appear to change this risk.18 A meta-analysis2 comparing restorative proctocolectomy with and without ileostomy showed that there is a non-significant trend towards lower rates of bowel obstruction as long-term adverse event in patients without ileostomy (odds ratio = 0.65, 95 % CI = 0.38–1.12; P = 0.12). Possible reasons for this observation remain speculative; additional adhesions induced by stoma creation and reversal could be an explanation for a potentially higher risk of bowel obstruction in diverted patients.

Some limitations of our study have to be addressed. The studies included in the analysis were different in design and setting, and most of them were retrospective in nature. In most studies, morbidity of ileostomy reversal was not a primary outcome measure. The potential risk of publication bias (with the actual morbidity possibly being underestimated) has already been discussed. The pooled data of such different studies do not allow an analysis of the impact of certain factors, like patients′ risk factors, type of anastomosis, laparoscopic surgery, and others, on morbidity of ileostomy reversal.

Conclusion

The considerable morbidity of ileostomy reversal after restorative proctocolectomy reduces the benefit of temporary fecal diversion. However, ileostomy creation is still recommended, as it effectively reduces the total number of pouch-related septic complications, which in turn are the main risk factor for bad pouch function, impaired quality of life, or even pouch failure.

References

Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J 1978;2:85–88.

Weston-Petrides GK, Lovegrove RE, Tilney HS, Heriot AG, Nicholls RJ, Mortensen NJ, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. Comparison of outcomes after restorative proctocolectomy with or without defunctioning ileostomy. Arch Surg 2008;143:406–412.

Hueting WE, Buskens E, van der Tweel I, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Results and complications after ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a meta-analysis of 43 observational studies comprising 9,317 patients. Dig Surg 2005;22:69–79.

Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, Coffey JC, Heneghan HM, Kirat HT, Manilich E, Shen B, Martin ST. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg 2013;257:679–685.

Raval MJ, Schnitzler M, O′Connor BI, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Improved outcome due to increased experience and individualized management of leaks after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg 2007;246:763–770.

Heuschen UA, Allemeyer EH, Hinz U, Lucas M, Herfarth C, Heuschen G. Outcome after septic complications in J pouch procedures. Br J Surg 2002;89:194–200.

Sagap I, Remzi FH, Hammel JP, Fazio VW. Factors associated with failure in managing pelvic sepsis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA)--a multivariate analysis. Surgery 2006;140:691–703; discussion 703–694.

Farouk R, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH, Larson D. Incidence and subsequent impact of pelvic abscess after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1998;41:1239–1243.

Tulchinsky H, Cohen CR, Nicholls RJ. Salvage surgery after restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 2003;90:909–921.

Mennigen R, Senninger N, Bruwer M, Rijcken E. Impact of defunctioning loop ileostomy on outcome after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26:627–633.

Fajardo AD, Dharmarajan S, George V, Hunt SR, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW, Mutch MG. Laparoscopic versus open 2-stage ileal pouch: laparoscopic approach allows for faster restoration of intestinal continuity. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:377–383.

Araujo SE, Nahas SC, Seid VE, Marchini GS, Torricelli FC. Laparoscopy-assisted ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: surgical outcomes after 10 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2005;15:321–324.

Grobler SP, Hosie KB, Keighley MR. Randomized trial of loop ileostomy in restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 1992;79:903–906.

Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, Lucas M, Heuschen G, Herfarth C. One- or two-stage procedure for restorative proctocolectomy: rationale for a surgical strategy in ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 2001;234:788–794.

Ikeuchi H, Nakano H, Uchino M, Nakamura M, Noda M, Yanagi H, Yamamura T. Safety of one-stage restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1550–1555.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10.

Dolejs S, Kennedy G, Heise CP. Small bowel obstruction following restorative proctocolectomy: affected by a laparoscopic approach? J Surg Res 2011;170:202–208.

Selvaggi F, Sciaudone G, Limongelli P, Di Stazio C, Guadagni I, Pellino G, De Rosa M, Riegler G. The effect of pelvic septic complications on function and quality of life after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a single center experience. Am Surg 2010;76:428–435.

Gunnarsson U, Karlbom U, Docker M, Raab Y, Pahlman L. Proctocolectomy and pelvic pouch--is a diverting stoma dangerous for the patient? Colorectal Dis 2004;6:23–27.

Fonkalsrud EW, Thakur A, Roof L. Comparison of loop versus end ileostomy for fecal diversion after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg 2000;190:418–422.

Dolgin SE, Shlasko E, Gorfine S, Bekov K, Leleiko N. Restorative proctocolectomy in children with ulcerative colitis utilizing rectal mucosectomy with or without diverting ileostomy. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:837–840.

Edwards DP, Chisholm EM, Donaldson DR. Closure of transverse loop colostomy and loop ileostomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1998;80:33–35.

Bain IM, Patel R, Keighley MR. Comparison of sutured and stapled closure of loop ileostomy after restorative proctocolectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1996;78:555–556.

Khoo RE, Cohen MM, Chapman GM, Jenken DA, Langevin JM. Loop ileostomy for temporary fecal diversion. Am J Surg 1994;167:519–522.

Seow-Choen F, Ho YH, Goh HS. The ileo-anal reservoir: results from an evolving use of stapling devices. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1994;39:13–16.

Braun J, Schumpelick V. [Direct ileum pouch-anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Technique and complications]. Chirurg 1992;63:361–367.

Poppen B, Svenberg T, Bark T, Sjogren B, Rubio C, Drakenberg B, Slezak P. Colectomy-proctomucosectomy with S-pouch: operative procedures, complications, and functional outcome in 69 consecutive patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35:40–47.

de Silva HJ, de Angelis CP, Soper N, Kettlewell MG, Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP. Clinical and functional outcome after restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 1991;78:1039–1044.

Sugerman HJ, Newsome HH, Decosta G, Zfass AM. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis without a temporary diverting ileostomy. Ann Surg 1991;213:606–617; discussion 617–609.

Sutter PM, Schuppisser JP, Ackermann C, Herzog U, Tondelli P. [Early and long-term results following ileum-anal pouch anastomosis]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1991;121:741–743.

Lewis P, Bartolo DC. Closure of loop ileostomy after restorative proctocolectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1990;72:263–265.

Matikainen M, Santavirta J, Hiltunen KM. Ileoanal anastomosis without covering ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1990;33:384–388.

Wexner SD, Wong WD, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM. The ileoanal reservoir. Am J Surg 1990;159:178–183; discussion 183–175.

Feinberg SM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z. Complications of loop ileostomy. Am J Surg 1987;153:102–107.

Harms BA, Hamilton JW, Yamamoto DT, Starling JR. Quadruple-loop (W) ileal pouch reconstruction after proctocolectomy: analysis and functional results. Surgery 1987;102:561–567.

Nasmyth DG, Williams NS, Johnston D. Comparison of the function of triplicated and duplicated pelvic ileal reservoirs after mucosal proctectomy and ileo-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg 1986;73:361–366.

Metcalf AM, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Beart RW, Jr., Wolff BG. Ileal "J" pouch-anal anastomosis. Clinical outcome. Annals of surgery 1985;202:735–739.

Nicholls RJ, Pezim ME. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis: a comparison of three reservoir designs. Br J Surg 1985;72:470–474.

de Montbrun SL, Johnson PM. Proximal diversion at the time of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: current practices of North American colorectal surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1178–1183.

Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 2003;238:229–234.

Cohen Z, McLeod RS, Stephen W, Stern HS, O′Connor B, Reznick R. Continuing evolution of the pelvic pouch procedure. Ann Surg 1992;216:506–511; discussion 511–502.

Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Milsom JW, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Fabre JM. Omission of temporary diversion in restorative proctocolectomy--is it safe? Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:1007–1014.

Williamson ME, Lewis WG, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, Johnston D. One-stage restorative proctocolectomy without temporary ileostomy for ulcerative colitis: a note of caution. Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:1019–1022.

Aberg H, Pahlman L, Karlbom U. Small-bowel obstruction after restorative proctocolectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:637–642.

Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Gorgun E, Ooi BS, Hammel J, Preen M, Church JM, Madbouly K, Lavery IC. The outcome after restorative proctocolectomy with or without defunctioning ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:470–477.

Kiran RP, da Luz Moreira A, Feza H. Remzi FH, Church JM, Lavery I, Hammel J, Fazio VW. Factors Associated With Septic Complications After Restorative Proctocolectomy. Ann Surg 2010;251:442–446.

Davies M, Hawley PR. Ten years experience of one-stage restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1255–1260.

Lovegrove RE, Symeonides P, Tekkis PP, Goodfellow PB, Shorthouse AJ. A selective approach to restorative proctocolectomy without ileostomy: a single centre experience. Colorectal Dis 2008;10:916–924.

Chow A, Tilney HS, Paraskeva P, Jeyarajah S, Zacharakis E, Purkayastha S. The morbidity surrounding reversal of defunctioning ileostomies: a systematic review of 48 studies including 6,107 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 2009;24:711–723.

Luglio G, Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Cima RR, Nelson H. Loop ileostomy reversal after colon and rectal surgery: a single institutional 5-year experience in 944 patients. Arch Surg 2011;146:1191–1196.

van Westreenen HL, Visser A, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA. Morbidity related to defunctioning ileostomy closure after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and low colonic anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:49–54.

D′Haeninck A, Wolthuis AM, Penninckx F, D′Hondt M, D′Hoore A. Morbidity after closure of a defunctioning loop ileostomy. Acta Chir Belg 2011;111:136–141.

Akesson O, Syk I, Lindmark G, Buchwald P. Morbidity related to defunctioning loop ileostomy in low anterior resection. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:1619–1623.

Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. Loop ileostomies in colorectal cancer patients--morbidity and risk factors for nonreversal. J Surg Res 2012;178:708–714.

El-Hussuna A, Lauritsen M, Bulow S. Relatively high incidence of complications after loop ileostomy reversal. Dan Med J 2012;59:A4517.

Peacock O, Law CI, Collins PW, Speake WJ, Lund JN, Tierney GM. Closure of loop ileostomy: potentially a daycase procedure? Tech Coloproctol 2011;15:431–437.

Baraza W, Wild J, Barber W, Brown S. Postoperative management after loop ileostomy closure: are we keeping patients in hospital too long? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:51–55.

Mennigen R, Senninger N, Bruewer M, Rijcken E. Pouch function and quality of life after successful management of pouch-related septic complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2012;397:37–44.

Selvaggi F, Pellino G, Canonico S, Sciaudone G. Is omitting pouchography before ileostomy takedown safe after negative clinical examination in asymptomatic patients with pelvic ileal pouch? An observational study. Tech Coloproctol 2012;16:415–420.

Loffler T, Rossion I, Bruckner T, Diener MK, Koch M, von Frankenberg M, Pochhammer J, Thomusch O, Kijak T, Simon T, Mihaljevic AL, Kruger M, Stein E, Prechtl G, Hodina R, Michal W, Strunk R, Henkel K, Bunse J, Jaschke G, Politt D, Heistermann HP, Fusser M, Lange C, Stamm A, Vosschulte A, Holzer R, Partecke LI, Burdzik E, Hug HM, Luntz SP, Kieser M, Buchler MW, Weitz J. HAnd Suture Versus STApling for Closure of Loop Ileostomy (HASTA Trial): results of a multicenter randomized trial (DRKS00000040). Ann Surg 2012;256:828–835; discussion 835–826.

Hiranyakas A, Rather A, da Silva G, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Loop ileostomy closure after laparoscopic versus open surgery: is there a difference? Surg Endosc 2013;27:90–94.

Royds J, O′Riordan JM, Mansour E, Eguare E, Neary P. Randomized clinical trial of the benefit of laparoscopy with closure of loop ileostomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:1295–1301.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mennigen, R., Sewald, W., Senninger, N. et al. Morbidity of Loop Ileostomy Closure after Restorative Proctocolectomy for Ulcerative Colitis and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis: a Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg 18, 2192–2200 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2660-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2660-8