Abstract

Purpose

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated that a laparoscopic approach provides short-term benefits, such as reduced blood loss and a shorter hospital stay, in patients who undergo rectal surgery. On the other hand, a few RCTs investigating proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) for ulcerative colitis (UC) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) suggested limited advantages of laparoscopic surgery over open surgery. A substantial proportion of patients with UC or FAP may undergo staged operations with IPAA, but no study has compared the two approaches for proctectomy with IPAA after total abdominal colectomy.

Methods

We examined 61 consecutive patients with UC or FAP who underwent proctectomy with IPAA after colectomy in our hospital. Patients were divided into the Lap group (n = 37) or the Op group (n = 24) according to surgical approach. Patient background and outcomes, such as operative time, blood loss, first bowel movement, postoperative complications, and pouchitis, were compared between these groups.

Results

One patient required conversion to open surgery in the Lap group. The median volume of blood loss was 90 mL in the Lap group and 580 mL in the Op group (p < 0.0001). The Lap group showed a shorter time to first bowel movement than the Op group (median: 1 vs 2 days, p = 0.0003). The operative time, frequencies of postoperative complications, and accumulation rate of pouchitis were similar between the two groups.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery was beneficial for patients undergoing restorative proctectomy in terms of blood loss and bowel recovery without increasing the operative time or rate of complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal-anastomosis (IPAA), first described by Parks and Nicholls [1], has become the standard for surgical treatment in patients in whom medical therapy for ulcerative colitis (UC) failed, or who developed colitis-associated cancer or dysplasia [2, 3]. The procedures are also indicated for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients who have a high risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) [4, 5]. One-stage proctocolectomy with IPAA can be performed on patients with otherwise minimal comorbidities as it has the advantages of lower cost and shorter hospitalization, and avoids temporary fecal diversion. However, in cases of refractory medical management, especially fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, and perforation, emergency colectomy is first selected [6]. In addition, FAP patients who undergo total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis may develop cancer in the residual rectum metachronously. Therefore, a substantial proportion of patients with UC or FAP may undergo proctocolectomy with IPAA in two or three stages [6].

Great advances in laparoscopic surgery have been made within the last two decades in many areas, including the colorectum, with less blood loss, faster postoperative recovery, fewer complications, and better cosmetic outcomes [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], although oncological outcomes have been controversial among randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing laparoscopic and open approaches for rectal cancer [12,13,14,15]. As such, surgeons have attempted to apply laparoscopic techniques for IPAA. Previous cohort studies and case-matched series investigating laparoscopic total proctocolectomy with IPAA for UC suggested several advantages, such as faster bowel function recovery and shorter hospital stay, over open surgery [17,18,19,20]. However, only a few RCTs were conducted for comparison between hand-assisted or fully laparoscopic and open proctocolectomy with IPAA for UC or FAP; the results of these RCTs suggested that the benefits of laparoscopic IPAA were limited [21, 22]. Moreover, there has been no study comparing the two approaches for proctectomy with IPAA after total abdominal colectomy as the second-stage surgery. A staged approach is generally considered a safer option for high-risk patients receiving IPAA such as those who are malnourished, anemic, or have physical deterioration due to uncontrolled inflammation [6]. In addition, potential intra-abdominal adhesions due to the past colectomy and suboptimal trocar positions may make laparoscopic proctectomy and IPAA more challenging.

In the current study, we compared the perioperative and postoperative outcomes of restorative proctectomy as a staged operation between laparoscopic and open approaches.

Materials and methods

Patients and classification

We retrospectively examined consecutive patients who underwent proctectomy and IPAA after total or subtotal abdominal colectomy in the University of Tokyo Hospital between January 2001 and November 2021. We excluded patients who underwent proctectomy without pouch surgery such as abdominoperineal resection and the Hartmann procedure.

Patients were classified into the laparoscopic group (“Lap group”) or open group (“Op group”) by the surgical approach for proctectomy.

This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital (reference number: 3252-13). For inclusion in the current study, written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the opportunity to opt-out was also offered.

Surgery

The indications and procedures of IPAA were described previously [23]. We scheduled handsewn IPAA with mucosectomy for patients with neoplasia or severe inflammation around the lower rectum, and stapled IPAA for UC patients without neoplasia or severe inflammation.

First, ileostomy and mucus fistula were closed whether the preceding colectomy was performed by open surgery (Fig. 1a) or laparoscopically (Fig. 1b). In laparoscopic proctectomy, the sites of the ileostomy and mucus fistula (when in the left lower quadrant) were then utilized for trocar placement (Fig. 1c), and additional trocars and a camera port at the umbilicus were placed. Thus, the position of the trocar for the surgeon’s left hand was shifted medial to the standard position in rectal surgery (Fig. 1d). Surgical resection of the rectum was performed based on total mesorectal excision (TME) [24] regardless of disease type. The mesentery of the ileum was fully mobilized before making an ileal J-pouch extracorporeally. When necessary, a few SMA branches towards the ileal pouch were divided and the mesentery was fenestrated. After anal anastomosis, a leak test was performed and loop ileostomy created above the pouch. An abdominal tube was placed towards the pelvis and a decompression tube was placed in the pouch through the anastomosis. If the pouch did not reach the anus, open conversion was attempted in order to carefully push the pouch into the pelvis manually until anastomosis was completed. When the pouch did not reach even after open conversion, the surgical procedure was changed to abdominoperineal resection.

Trocar placement for laparoscopic proctectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis after total abdominal colectomy in our hospital. Gray circles indicate ileostomy and mucus fistula, and closed circles indicate trocars. Dashed lines indicate surgical scars. a Typical status after colectomy with ileostomy and mucus fistula via open surgery. A mucus fistula may be created in the left lower quadrant. b Typical status after total colectomy with ileostomy and mucus fistula via laparoscopic surgery. c Ileostomy and mucus fistula (when in the left lower quadrant) were utilized as trocar sites after closure. Two additional trocars and a camera port at the umbilicus were placed. d Standard trocar position in laparoscopic surgery for sporadic rectal cancer

The laparoscopic approach was applied for early CRC in our hospital around 2003, and that for advanced CRC was standardized after 2012, as reported previously [25]. Laparoscopic colorectal resections for UC and FAP were gradually introduced in a similar time course.

Data collection

Demographic data, such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking habit (never or ex-/current smoker), serum levels of albumin, hemoglobin before surgery, type of disease (refractory UC, CAC/dysplasia, or FAP), and past treatments for UC, such as 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), steroids, immunomodulators, antibodies, and granulocyte and monocyte apheresis (GMA), were retrospectively obtained from medical records. Surgery-related parameters, such as total number of staged operations (two or three), surgical approach for the preceding colectomy, period of IPAA (2001–2010 or 2011–2021), type of IPAA (stapled or handsewn), diverting stoma, operative time for proctectomy and IPAA, estimated blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, conversion to open surgery, postoperative complications, first bowel movement and hospital stay after IPAA, pouchitis, and pouch failure, were collected from medical charts. Postoperative complications were categorized and assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification [26].

Statistical analysis

Categorized data were compared by the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact probability test, whereas continuous variables were compared by the Student t-test or Wilcoxon test. The accumulated incidence of pouchitis was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and analyzed by the log-rank test. All analyses were performed using JMP software ver. 15.1.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and associations were considered significant when a p value was < 0.05.

Results

Patient overview

A total of 64 patients received proctectomy as a stage surgery after total abdominal colectomy for UC or FAP during the study period. After excluding three patients who did not undergo pouch surgery, 61 patients were examined in the subsequent analyses (Fig. 2).

The preoperative clinical data of the patients according to the surgical approach for restorative proctectomy are summarized in Table 1. Overall, UC outnumbered FAP as the background disease, with refractory UC being more frequent than CAC or dysplasia. In all patients with CAC or dysplasia, the diagnosis was first made by histological evaluation of the resected specimen of total abdominal colectomy aiming to control refractory inflammation or acute exacerbation. All FAP patients received ileorectal anastomosis decades ago and developed metachronous cancer. The mean albumin level was lower in the Lap group than in the Op group (3.8 g/dL vs 4.1 g/dL, p = 0.013). Immunomodulators, antibodies, and GMA were more frequently used in the Lap group, whereas there was no difference in 5-ASA or steroid use between the groups.

Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic vs open restorative proctectomy

Parameters related to surgical treatments between the Lap and Op groups are shown in Table 2. Most patients underwent three-stage operations in the Lap group (97%); in contrast, modified two-staged operations without diverting stoma were selected for 71% in the Op group (p < 0.0001). Total abdominal colectomy was performed previously via a laparoscopic approach in 65% of the Lap group, whereas all patients of the Op group underwent open colectomy as the first surgery (p < 0.0001). Ileorectal anastomosis was previously performed on two FAP patients who underwent resection of the rectum bearing metachronous cancer. No marked differences were observed in the frequencies of stapled or handsewn IPAA between the two groups. Conversion to open surgery was noted in only one patient (3%) of the Lap group because of dense intra-abdominal adhesions, but there was no case of the ileal pouch not reaching the anus.

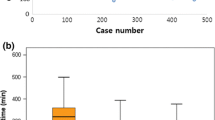

The operative time for proctectomy and IPAA in the Lap group was 44 min longer than that in the Op group, but the difference was not significant. In contrast, the estimated volume of blood loss was markedly lower in the Lap group than in the Op group (median: 90 mL vs 580 mL, p < 0.0001). Moreover, six patients (25%) required blood transfusion during surgery in the Op group (vs 0% in the Lap group, p = 0.002).

Postoperative complications are summarized in Table 3. There was no significant difference in overall morbidities between the Lap and Op groups. Moreover, no intergroup difference was observed in each morbidity. Four patients of the Lap group developed grade 3 complications (peritoneal abscess formation in 2, anastomotic bleeding in 1, and cholecystitis in 1), whereas a patient who underwent open proctectomy without a diverting stoma experienced anastomotic leakage on day 9 which required emergency surgery (abdominal drainage and stoma creation). Of note, stoma outlet obstruction (SOO) developed in 11 patients (30%) of the Lap group who underwent loop ileostomy creation (n = 36), whereas all six patients who underwent open IPAA with diverting stoma were free from SOO (p = 0.16). SOO was treated conservatively by inserting a decompression tube from the stoma in all patients.

The Lap group showed a shorter time to bowel movement than the Op group (median: 1 day vs 2 days, p = 0.0003). The duration of hospital stay after surgery was similar between the two groups. No mortality within 30 days of surgery was documented in either group.

Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic vs open restorative proctectomy

Lastly, long-term outcomes were assessed. The median follow-up time was 63.5 months. As shown in Fig. 3, the incidence of pouchitis in the Lap group did not differ from that in the Op group (p = 0.75). No pouch failure was observed during the follow-up period. One patient in the Op group (4%) died of catheter-related sepsis that was not associated with CAC or pouchitis 7.7 years after handsewn IPAA, and one patient in the Lap group (3%) died of primary lung cancer with brain metastasis 7.7 years after stapled IPAA.

Discussion

The current study was the first to compare the surgical outcomes of laparoscopic and open proctectomy and IPAA after total abdominal colectomy for UC or FAP. It demonstrated that the laparoscopic approach significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss during surgery without affecting other perioperative postoperative parameters.

Regarding total restorative proctocolectomy, previous RCTs failed to demonstrate a reduction in intraoperative blood loss via a laparoscopic approach [21, 22], which is in contrast to RCTs for CRC reporting that laparoscopic colectomy or rectal surgery is favorable regarding this endpoint [7,8,9,10, 12,13,14,15]. Our study revealed a clear advantage of laparoscopic proctectomy and IPAA as a staged operation in terms of blood loss. More complicated and technically demanding surgical procedures in panproctocolectomy plus IPAA increase the chance of bleeding via any approach, which may reduce this benefit.

On the other hand, several studies reported that the operative time for total proctocolectomy plus IPAA was prolonged by a laparoscopic approach [19, 21, 22]. In contrast, the difference in the operative time for restorative proctectomy between the two groups was not significant in the current study despite suboptimal port placement for laparoscopic surgery. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of type II error, the experience of expert surgeons may have avoided this issue.

Conversion to open surgery was required in only 3% in the Lap group in the present study. This satisfactory rate was lower than the reported percentage of conversion (24%) for laparoscopic proctocolectomy in a previous RCT [22] and the pooled conversion rate (5.5%) in a meta-analysis including nine non-randomized cohort studies or case-matched series [20]. A sufficient working space after total abdominal colectomy may lead to the reduced possibility of conversion compared with proctocolectomy.

Previous meta-analyses favored laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy over open surgery in terms of bowel recovery and hospital stay [17,18,19,20]. The current study showed a shorter time to first bowel movement in the Lap group. Nevertheless, both groups showed long durations of hospitalization without significant difference. This can be explained by the following reasons: Japan’s statutory health insurance programs provide a fixed rate of hospitalization costs regardless of its length. Thus, patients are likely to leave hospital only when they have no severe complications, are able to take similar amount of food to preoperative levels, and have no excessive stress of living at home. Potentially, laparoscopic approach may have decreased hospital days, but a diverting ileostomy was created in many patients; it took much time for them to take care of their stoma by themselves with confidence.

Several systematic reviews showed that complication rates of laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy were lower than open surgery [19, 20], whereas others failed to demonstrate the advantages [17, 18]. In the current study, no marked differences in postoperative complication rates were found between the approaches for proctectomy. On the other hand, we acknowledged an increased frequency of SOO (30%) in the Lap group, although not significant. SOO developed in 5–7% during surgery for sporadic rectal cancer [27,28,29], but the frequency was higher (17–27%) in patients who underwent IPAA for UC [27, 30,31,32]. Reported risk factors included high-output stoma, loop ileostomy, age younger than 16 years, low BMI < 21, abdominal rectal muscle thickness ≥ 10 mm, and subcutaneous fat thickness at the stoma site ≥ 20 mm [27,28,29,30, 32]. Loop ileostomy is well accepted as a method to mitigate the incidence of anastomotic leakage. In addition, we routinely created a diverting stoma in recent cases because the use of antibodies almost coincided with the application of laparoscopic surgery in our hospital. Initial reports suggested that infliximab increases morbidities in IPAA [33, 34]. Whether the use of antibodies increases overall or pouch-related complications of IPAA is under debate [35,36,37]. Therefore, decision of creating a diverting stoma should be based on the trade-off relationship between the risks of these postoperative complications and SOO. Laparoscopic IPAA without a stoma (modified two-stage restorative proctocolectomy) may be a realistic option when the leak test is negative in the future, as there was no anastomotic leakage in 37 consecutive patients of the Lap group.

There are several limitations of the current study due to its retrospective nature and inherent biases. The total number of patients analyzed was relatively small. The study period was relatively long, and progress in the perioperative management and treatment of UC over time may influence surgical outcomes. As laparoscopic surgery was performed mostly in the later period, patients treated by immunomodulators, antibodies, or GMA in the Lap group outnumbered those in the Op group. Furthermore, there were differences in other patient characteristics, such as serum albumin level and approach of the preceding colectomy, between the Lap and Op groups. Lastly, we did not address cosmesis or bowel function outcomes because of the difference in stoma creation rate between the two groups.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that laparoscopic restorative proctectomy after total abdominal colectomy is safe and beneficial for patients in terms of intraoperative blood loss and postoperative bowel recovery regardless of a suboptimal condition for rectal surgery. Our study results should be confirmed using a larger number of patients.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are derived from the patient database of the hospital and hence subject to confidentiality, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Parks AG, Nicholls RJ (1978) Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J 2:85–88

Williams NS (1989) Restorative proctocolectomy is the first choice elective surgical treatment for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 76:1109–1110

Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK (1995) Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg 222:120–127

Kartheuser A, Parc R, Penna C, Tiret E, Frileux P, Hannoun L, Nordlinger B, Loygue J (1996) Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis as the first choice operation in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. A ten-year experience. Surgery 119:615–623

Nyam DC, Brillant PT, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG (1997) Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg 226:514–521

Thompson DT, Hrabe JE (2021) Staged approaches to restorative proctocolectomy with ileoanal pouch—when and why? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2021.0060

Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J (2002) Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 359:2224–2229

The Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group (2004) A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2050–2059

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM, MRC CLASICC trial group (2005) Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365:1718–1726

Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M, Lacy AM, COlon cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group (COLOR) (2005) Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 6:477–484

Kitano S, Inomata M, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Watanabe M, Yamamoto S, Ito M, Saito S, Fujii S, Konishi F, Saida Y, Hasegawa H, Akagi T, Sugihara K, Yamaguchi T, Masaki T, Fukunaga Y, Murata K, Okajima M et al (2017) Survival outcomes following laparoscopic versus open D3 dissection for stage II or III colon cancer (JCOG0404): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:261–268

Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, Choi HS, Kim DW, Chang HJ, Kim DY, Jung KH, Kim TY, Kang GH, Chie EK, Kim SY, Sohn DK, Kim DH, Kim JS, Lee HS et al (2014) Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:767–774

Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Lacy AM, Bemelman WA, Andersson J, Angenete E, Rosenberg J, Fuerst A, Haglind E, COLOR II Study Group (2015) A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 372:1324–1332

Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M, Peters WR Jr, Maun D, Chang G, Herline A, Fichera A, Mutch M, Wexner S, Whiteford M, Marks J, Birnbaum E, Margolin D, Larson D, Marcello P et al (2015) Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:1346–1355

Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ, Davies L, Wilson K, Hague W, Simes J, ALaCaRT Investigators (2015) Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALaCaRT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:1356–1363

Matsumoto S, Bito S, Fujii S, Inomata M, Saida Y, Murata K, Saito S (2016) Prospective study of patient satisfaction and postoperative quality of life after laparoscopic colectomy in Japan. Asian J Endosc Surg 9:186–191

Tan JJ, Tjandra JJ (2006) Laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis—a meta-analysis. Color Dis 8:626–636

Ahmed Ali U, Keus F, Heikens JT, Bemelman WA, Berdah SV, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ (2009) Open versus laparoscopic (assisted) ileo pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD006267

Wu XJ, He XS, Zhou XY, Ke J, Lan P (2010) The role of laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Color Dis 25:949–957

Bartels SA, Gardenbroek TJ, Ubbink DT, Buskens CJ, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA (2013) Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open colectomy with end ileostomy for non-toxic colitis. Br J Surg 100:726–733

Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA, Gouma DJ, van Deventer SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Bemelman WA (2004) Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 240:984–991

Schiessling S, Leowardi C, Kienle P, Antolovic D, Knebel P, Bruckner T, Kadmon M, Seiler CM, Büchler MW, Diener MK, Ulrich A (2013) Laparoscopic versus conventional ileoanal pouch procedure in patients undergoing elective restorative proctocolectomy (LapConPouch Trial)—a randomized controlled trial. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 398:807–816

Emoto S, Hata K, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T, Shuno Y, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Murono K, Iida Y, Ishii H, Yokoyama Y, Anzai H, Sonoda H, Ishihara S (2021) Risk factors for non-reaching of ileal pouch to the anus in laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with handsewn anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. https://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2020.00158

Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD (1982) The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery—the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg 69:613–616

Nozawa H, Ishizawa T, Yasunaga H, Ishii H, Sonoda H, Emoto S, Murono K, Sasaki K, Kawai K, Akamatsu N, Kaneko J, Arita J, Hasegawa K, Ishihara S (2021) Open and/or laparoscopic one-stage resections of primary colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastases. Medicine 100:e25205

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications. A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Okada S, Hata K, Emoto S, Murono K, Kaneko M, Sasaki K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kawai K, Nozawa H (2018) Elevated risk of stoma outlet obstruction following colorectal surgery in patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Today 48:1060–1067

Tamura K, Matsuda K, Yokoyama S, Iwamoto H, Mizumoto Y, Murakami D, Nakamura Y, Yamaue H (2019) Defunctioning loop ileostomy for rectal anastomoses: predictors of stoma outlet obstruction. Int J Color Dis 34:1141–1145

Sasaki S, Nagasaki T, Oba K, Akiyoshi T, Mukai T, Yamaguchi T, Fukunaga Y, Fujimoto Y (2021) Risk factors for outlet obstruction after laparoscopic surgery and diverting ileostomy for rectal cancer. Surg Today 51:366–373

Okita Y, Araki T, Kondo S, Fujikawa H, Yoshiyama S, Hiro J, Inoue M, Toiyama Y, Kobayashi M, Ohi M, Inoue Y, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M (2017) Clinical characteristics of stoma-related obstruction after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg 21:554–559

Ohira G, Miyauchi H, Hayano K, Kagaya A, Imanishi S, Tochigi T, Maruyama T, Matsubara H (2018) Incidence and risk factor of outlet obstruction after construction of ileostomy. J Anus Rectum Colon 2:25–30

Kitahara T, Sato Y, Oshiro T, Matsunaga R, Nagashima M, Okazumi S (2020) Risk factors for postoperative stoma outlet obstruction in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointestinal Surg 12:507–519

Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Harrington JR, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, Wolff BG, Pemberton JH (2007) Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg 204:956–962

Schluender SJ, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, Vasiliauskas EA, Papadakis KA, Mei L, Targan SR, Fleshner PR (2007) Does infliximab influence surgical morbidity of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis? Dis Colon Rectum 50:1747–1753

Selvaggi F, Pellino G, Canonico S, Sciaudone G (2015) Effect of preoperative biologic drugs on complications and function after restorative proctocolectomy with primary ileal pouch formation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21:79–92

Yang Z, Wu Q, Wang F, Wu K, Fan D (2012) Meta-analysis: effect of preoperative infliximab use on early postoperative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing abdominal surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 36:922–928

Hicks CW, Hodin RA, Bordeianou L (2013) Possible overuse of 3-stage procedures for active ulcerative colitis. JAMA Surg 148:658–664

Funding

Hiroaki Nozawa is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Challenging Research (Exploratory): grant number: 20K21626, and B: grant number: 21H02778). Shigenobu Emoto is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (C: grant number: 19K09115).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: HN, KH, and SI; acquisition of data: HN, KS, KM, KK, SE; analysis and interpretation of data: HN, KH, KS, and SI; drafting of manuscript: HN; critical revision of manuscript: KH, KS, KM, KK, SE, and SI

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital.

Consent to participate

For inclusion in the current study, written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the opportunity to opt-out was also offered.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the present article and authorized its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nozawa, H., Hata, K., Sasaki, K. et al. Laparoscopic vs open restorative proctectomy after total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 1605–1612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02492-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02492-x