Abstract

Background

Pyloromyotomy by single-incision pediatric endosurgery (SIPES) is a new technique that leaves virtually no appreciable scar. So far, it has not been compared to conventional laparoscopic (CL) pyloromyotomy. This study compares the results of the first 15 SIPES pyloromyotomies of a surgeon to his last 15 CL cases.

Methods

Data were collected on all SIPES pyloromyotomies. Age, gender, operative time, estimated blood loss, conversion/complication rate, and outcome in the SIPES patients were compared to the CL cohort.

Results

There was no difference in age, weight, gender, blood loss, or hospital stay. A trend toward shorter operating time was found in the CL group (21.7 ± 9.9 versus 30.3 ± 15.8, p = 0.08, 95%CI 20.9–39.7 min). Two mucosal perforations occurred in the SIPES cohort. Both cases were converted to conventional laparoscopy, the defect was repaired, and both patients had an uncomplicated postoperative course. There were no wound infections or conversions to open surgery. Parents were uniformly pleased with the cosmetic results of SIPES.

Conclusion

SIPES pyloromyotomy may have a higher perforation rate than the CL approach. If recognized, a laparoscopic repair is feasible. Improved cosmesis must be carefully weighed against the potentially increased risks of SIPES versus conventional laparoscopic pyloromyotomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pyloromyotomy by single-incision pediatric endosurgery (SIPES) has recently been described1 and is a new laparoscopic approach that leaves virtually no appreciable scar. More than 25 of these procedures have been performed in our hospital so far. To date, studies comparing conventional laparoscopic and SIPES pyloromyotomy have not been published.

In order to evaluate the risks and benefits of SIPES pyloromyotomy and whether improved cosmesis is worth giving up the advantages of conventional laparoscopic instrument triangulation, the results of the first 15 SIPES pyloromyotomies of a single surgeon were compared to those of the surgeon’s last 15 conventional laparoscopic cases.

Material and Methods

After IRB approval (protocol no. X090814001), data were prospectively collected on all SIPES pyloromyotomies performed at our institution, including age, gender, operative time, estimated blood loss, conversion and complication rate, as well as time to hospital discharge reflecting time to full oral feeds. Clinical outcome and parent satisfaction at ambulatory follow-up 1 to 4 weeks later was assessed as well. Data for the conventional laparoscopic pyloromyotomies were collected by retrospective chart review. The parameters of the surgeon’s first 15 SIPES cases were compared to his last 15 conventional laparoscopic cases. Dichotomous variables were compared using Fischer’s exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed by Student’s t test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

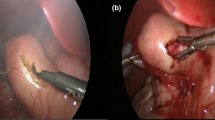

The diagnosis of pyloric stenosis was confirmed by ultrasound in all patients. A muscular wall thickness of over 4.0 mm or a pyloric length of 1.6 cm or greater was considered positive for the diagnosis. The patients were admitted for iv hydration and the surgery was performed once the serum bicarbonate level was below 30 mg/dl and the chloride concentration was above 90 mmol/l. The technique for SIPES pyloromyotomy has been previously described,1 while the technique of laparoscopic pyloromyotomy has been well established and evaluated at our institution.2,3 The main difference of the two techniques was the location of the 3-mm working instruments. In the conventional laparoscopic approach, these were placed into the abdomen through separate full-thickness stab incisions in the right and left upper quadrants. In the SIPES procedure, they were introduced through a single 1-cm horizontal skin incision in the umbilicus, lateral on both sides of the optical port (Fig. 1).

Instrument configuration for SIPES pyloromyotomy. The pylorus is stabilized by holding the proximal duodenum with a grasper in the surgeon’s left hand. This orients the pylorus in an oblique fashion toward the left upper quadrant, which facilitates incising the serosa longitudinally. The arthrotomy knife is then replaced by a second grasper to bluntly spread the muscle layer down to the submucosa.

Results

There was no significant difference between the groups in age, weight, gender, pyloric dimensions, blood loss, complication rate, or length of stay (Table 1). A trend toward shorter operating time was found in the conventional laparoscopic group (21.7 ± 9.9 versus 30.3 ± 15.8 min, p = 0.08, 95%CI 20.9–39.7 min).

Two perforations occurred in the SIPES cohort. In one case, after completing the spread of the muscular layers, there was a small perforation visible in the pyloric mucosa at the duodenal aspect. The case was immediately converted to angulated conventional laparoscopy with two 3-mm stab incisions in the right and left upper quadrants. The defect was closed using two simple 4–0 polyglactin sutures using intracorporeal knot tying. Fibrin glue was applied to the muscular gap and an omental patch was placed onto the pylorus for reinforcement. In the second patient, the pyloromyotomy was completed using the single-incision approach without difficulty. Upon inspecting the pylorus, a small traumatic full-thickness perforation was noticed in the anterior proximal duodenum where the left-hand grasper had been placed to stabilize the pylorus during the cut and spread. After converting to conventional laparoscopy, the defect was sutured using three inverting (Lambert-type) 4–0 polyglactin sutures. Both patients were kept NPO overnight with a nasogastric tube in place to gravity drainage. The following morning, an upper gastrointestinal contrast study was obtained, which showed normal passage of contrast and no leak in both cases. The patients were given ad lib feeds and discharged home in the afternoon of the first postoperative day.

When both patients with perforation were excluded from the statistical analysis, the operation times for SIPES and laparoscopic pyloromyotomy were more similar (25.2 ± 9.4 versus 21.7 ± 9.9 min, respectively, p = 0.34).

There were no wound infections or conversions to open surgery in either group. One patient was readmitted with persistent vomiting after conventional laparoscopy, but eventually discharged home on ranitidine and metoclopramide for gastroesophageal reflux.

All patients were seen in our ambulatory clinic 1 to 3 weeks after the operation. Parents were uniformly pleased with the cosmetic results of SIPES. Upon questioning, the parents of all 15 patients in whom the SIPES approach was attempted said they would chose the procedure again if a future sibling required a pyloromyotomy.

Discussion

Single-incision laparoscopy is becoming a routine approach for many standard surgical procedures such as appendectomy4 and cholecystectomy.5 Pyloromyotomy is one of the most frequently performed operations in pediatric surgery. Since March 2009, we have offered single-incision endosurgical pyloromyotomy to our patient, and our initial experience has recently been published.1

In this study, the cases of a single surgeon were included to minimize the effect of technical variability, personal experience, and instrumentation preference on the outcomes and thereby make the study cohorts more comparable. Because the single-incision approach was offered to all parents after March 2009, and all parents agreed to it, selection bias was avoided. This is confirmed by the comparable preoperative characteristics of both groups.

Likewise, there was no statistical difference in the outcome variables. The longer mean operating time in the SIPES group was mostly due to conversion to triangulated laparoscopy and the repair of the defect in the patients with perforation. However, the SIPES operating times were within the mean operating times of conventional laparoscopic pyloromyotomy (20 to 31 min) reported in the literature.6–8

Although not statistically proven, SIPES pyloromyotomy may have a higher perforation rate than the conventional laparoscopy. A high index of suspicion for this problem is warranted because if it is recognized intraoperatively, a laparoscopic repair can be performed without postoperative sequellae. It is crucial to inspect the antrum, the pylorus along with the exposed mucosa, as well as the duodenum for any potential injuries after the completed pyloromyotomy. As in the laparoscopic procedure, care must be taken not to crush or stab the duodenal wall when stabilizing it with the left-hand grasper.

In the literature, a perforation rate as high as 8% to 9% has been reported for conventional laparoscopic pyloromyotomy.9–11 Nevertheless, the rate of two perforations in the 15 SIPES patients seem quite high, especially when comparing it to the conventional laparoscopic control group in this study. Partially, they may be attributed to the initial learning curve of a new technique. According to a study by Kim,12 the learning curve for conventional laparoscopic pyloromyotomy is the steepest in the first 15 cases and plateaus after about 30 cases. If this is correspondingly applicable to SIPES pyloromyotomy, the complication rate should decrease in the future.

Due to the possibility of perforation, SIPES pyloromyotomy should be done in centers where laparoscopic management of complications is possible. Otherwise, conversion to an open procedure would be necessary, which could increase morbidity and ultimately decrease parent satisfaction. When obtaining informed consent, it should be clearly stated that there may be a higher complication rate for SIPES and that conversion to conventional triangulated laparoscopy or an open surgical procedure is possible.

Correspondingly, a surgeon should not hesitate to convert if the SIPES operation becomes difficult or endoscopic vision is impaired. Some suggestions that may help facilitate the SIPES procedure are the use of a long endoscope with 45° optical angulation (to spatially separate the cameraman’s hand from the surgeon’s as much as possible) and working instruments of different lengths (to separate the surgeon’s hands from each other). In general, a more longitudinal working axis can be beneficial in SIPES cases as well. This can be accomplished by lining up the pylorus for the cut and spread in an oblique fashion, with the antral side pointing toward one to two o’clock instead of the more conventional horizontal alignment.1

Interestingly, one set of parents had heard of single-incision laparoscopy from a popular press article they had encountered on the Internet. The other parents did not comment on their knowledge of single-incision endosurgery preoperatively. None specifically asked for a single-incision approach.

A drawback of this study is that parent satisfaction was not formally quantitated in the SIPES group. Furthermore, data on parent satisfaction were not consistently queried or recorded in the retrospective conventional laparoscopic patients.

Conclusion

If performed with care, SIPES pyloromyotomy is a reasonable alternative to the standard laparoscopic approach, leaving almost no appreciable scar. Parent satisfaction is extremely high. However, improved cosmesis must be carefully weighed against a potentially higher perforation rate. A decline in the complication rate should be observed before SIPES pyloromyotomy can be universally recommended. The introduction of novel angulated instruments may help simplify the operation in the future. Ultimately, the parent’s expectations and choices will determine whether SIPES pyloromyotomy will become a popular treatment option.

References

Muensterer OJ, Adibe OO, Harmon CM, Chong A, Hansen EN, Bartle D, Georgeson KE. Single-incision laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2010; Dec 24. PMID: 20033707 (in press).

Haricharan RN, Aprahamian CJ, Morgan TL, Harmon CM, Georgeson KE, Barnhart DC. Smaller scars—-what is the big deal: a survey of the perceived value of laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:92–96.

Yagmurlu A, Barnhart DC, Vernon A, Georgeson KE, Harmon CM. Comparison of the incidence of complications in open and laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: a concurrent single institution series. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:292–296.

Hong TH, Kim HL, Lee YS, Kim JJ, Lee KH, You YK, Oh SJ, Park SM. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (TUSPLA): scarless intracorporeal appendectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2009;19:75–78.

Chamberlain RS, Sakpal SV. A comprehensive review of Single-Incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) and Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) Techniques for Cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1733–1740.

Peter SD, Holcomb III GW, Calkins CM Murphy JP, Andrews WS, Sharp RJ, Snyder CL, Ostlie DJ. Open versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for pyloric stenosis. A prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 2006;244: 363–370.

Kim SS, Lau ST, Lee SL, Schaller Jr R, Healey PJ, Ledbetter DJ, Sawin RS, Waldhausen JHT. Pyloromyotomy: a comparison of laparoscopic, circumumbilical, and right upper quadrant operative techniques. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:66–70.

Adibe OO, Nichol PF, Flake AW, Mattei P. Comparison of outcomes after laparoscopic and open pyloromyotomy at a high-volume pediatric teaching hospital. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:1676–1678.

Ford WD, Crameri JA, Holland AJ. The learning curve for laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:552–554.

Sitsen E, Bax NM, van der Zee DC. Is laparoscopic pyloromyotomy superior to open surgery? Surg Endosc 1998;12:813–815.

Campbell BT, McLean K, Barnhart DC, Drongowski RA, Hirschl RB. A comparison of laparoscopic and open pyloromyotomy at a teaching hospital. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:1068–1071.

Kim SS, Lau ST, Lee SL, Waldhausen JH. The learning curve associated with laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2005;15:474–477.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muensterer, O.J. Single-Incision Pediatric Endosurgical (SIPES) Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Pyloromyotomy: A Single-Surgeon Experience. J Gastrointest Surg 14, 965–968 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1199-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1199-6