Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review objectively evaluates the safety and outcomes of extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer involving critical adjacent vessels namely the superior mesenteric-portal veins, hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery, and celiac axis.

Methods

Electronic searches were performed on two databases from January 1995 to August 2009. The end points were: firstly, to evaluate the safety through reporting the mortality rate and associated complications and, secondly, the outcome by reporting the survival after surgery. This was synthesized through a narrative review with full tabulation of results of all included studies.

Results

Twenty-eight retrospective studies comprising of 1,458 patients were reviewed. Vein thrombosis and arterial involvement were reported as contraindications to surgery in 62% and 71% of studies, respectively. The median mortality rate was 4% (range, 0% to 17%). The median R0 and R1 rates were 75% (range, 14% to 100%) and 25% (range, 0% to 86%), respectively. In high volume centers, the median survival was 15 months (range, 9 to 23 months). Nine of 10 (90%) studies comparing the survival after extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection versus standard pancreaticoduodenectomy reported statistically similar (p > 0.05) survival outcomes. Undertaking vascular resection was not associated with a poorer survival.

Conclusions

The morbidity, mortality, and survival outcome after undertaking extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer with venous involvement and/or limited arterial involvement is acceptable in the setting of an expert referral center and should not be a contraindication to a curative surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The current curative treatment paradigm for pancreatic cancer entails a strategy of complete surgical resection combined with adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Randomized clinical trials have reported a median survival of approximately 22 months compared to 18 months in patients undergoing adjuvant therapy with gemcitabine chemotherapy after surgery compared to observation alone.1,2 When chemotherapy is combined with radiation therapy as a radio-sensitizer, the survival benefit appeared to be more pronounced with the chemoradiation group having a median survival of about 25 months compared to 19 months in patients undergoing observation alone.3 Although these strategies have not shown a significant difference in overall survival, they may delay the time to recurrence and may, therefore, be useful in treating patients with a microscopically positive margin (R1). In patients with unresectable tumors otherwise termed locally advanced pancreatic cancer, gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin evaluated in the GERCOR and GISCAD phase-III trial yielded a median survival of 9 months.4 When treated with chemoradiation, the median survival may increase to about 13 months as reported in the 2001-01 FFCD/SFRO study.5 The survival disparity in nonresectable tumors as compared to resectable tumors in these trials emphasizes the positive impact of a complete surgical resection (R0) and a rationale towards undertaking aggressive curative surgery where possible.

A common contraindication for resection in the current clinical practice for patients with locally advanced tumors (T3/T4 tumors) is the presence of vascular involvement of the critical adjacent vessels. However, there is a recognized arbitrary state of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer where tumors involve the superior mesenteric-portal veins but may remain relatively resectable with additional vascular surgical procedure. Hence, the definition of resectability may vary between different treatment centers with varying level of expertise and willingness to undertake extended pancreaticoduodenectomy. The concept of a regional pancreatectomy as first described by Fortner6 was an attempt to improve results of surgical resection of pancreatic cancer by performing a subtotal or total pancreatic resection which usually involves resection and reconstruction of the pancreatic segment of the portal vein, en bloc regional lymphadenectomy, and in highly selected cases resection and reconstruction of a major artery. Such extended pancreatectomy may facilitate resection in patients with tumors that are classified as T3/T4 and total clearance of the peripancreatic, hepatoduodenal, mesenteric, and celiac lymph nodes. The clinical benefit of extended pancreatic resections must, however, be balanced with the risk of the procedure. With regard to extended lymphadenectomy, its role as a routine procedure is no longer proven following evidence from randomized trials that showed no survival advantage and increased morbidity.7,8 It has been shown that the prognosis in patients with lymph node involvement is related more so to the number of nodes involved than just the nodal status itself.9 Therefore, lymphadenectomy may still have a role in the management of patients with nodal disease. Observations from a multicenter study of patients following R0/R1 pancreatectomy showed that patients with node positive disease are likely to benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation treatment.10 With regard to vascular resection as part of an extended pancreatectomy procedure, it continues to remain controversial due to the procedural complexity, the safety and consequential morbidity imposed on the patient in a disease that portends a poor survival, and the lack of randomized evidence to demonstrate its efficacy.

A previous systematic review by Siriwardana and colleague failed to recognize the heterogeneity in survival outcomes that reflected the expertise of the treatment center, hence, leading to an overstated conclusion that did not reflect the current consensus of expert pancreatic surgeons.11 More recently, a collective review of recent publications of pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection concluded that the procedure was safe, feasible, and provides important survival benefits.12 The objective of the current review serves to provide a systematic review with full tabulation of published studies with stratification of vessel (vein or artery) involvement and level of expertise (high- or low-volume centers) and to compare the extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular procedure to a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy alone to thoroughly supplement and establish the current evidence in this field.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

Original published studies on pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection of both veins and arteries for pancreatic cancer were identified by searching the MEDLINE database (1995 to August 2009) and PubMed (January 1995 to August 2009) using the keywords: “pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreatic cancer, vascular resection, portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, hepatic artery, celiac axis, and superior mesenteric artery.” The search was limited to human articles published in the English language. The reference lists of all retrieved articles were manually reviewed to further identify potentially relevant studies. All relevant articles identified were assessed with application of a predetermined selection criterion.

Selection Criteria

Studies which specifically addressed pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection and reported the complications, mortality, and survival outcomes were evaluated. Studies which reported vascular resection as a subset analysis in pancreatectomy without evaluating the mentioned endpoints of review or not comprehensively reported were excluded. To ensure that the sample size would not bias the reporting of the morbidity and mortality outcomes, only studies reporting more than 10 patients were included. For institutions reporting updated experiences, only the most recent or complete paper was selected for review. Studies were selected for evaluation if they were level I evidence: randomized controlled trials; level II evidence: nonrandomized controlled clinical trials or well-designed cohort studies; level III evidence: observational studies, as described by the US Preventive Services Task Force.

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

Two reviewers (T.C.C. and A.S.) independently critically appraised each article using a standard protocol. Data extracted include the methodology, quality criteria, perioperative variables, morbidity and mortality outcomes, and survival data. All data were extracted and tabulated from the relevant articles’ texts, tables, and figures. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. Following tabulation of the results, the morbidity, mortality, and survival outcomes were synthesized. Stratification was made based on whether the institution was considered as a high- or low-volume center by searching the literature for publications on pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. High-volume centers were assigned if prospective case series from the institution reported at least 20 pancreatic resection cases per year irrespective of the number of pancreatic surgeons in the institution. Meta-analysis was inappropriate because of the heterogeneous nature of the included studies and the lack of a controlled comparative arm.

Results

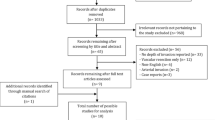

Quantity and Quality of Evidence

Literature search using the above-described search strategy through both MEDLINE and PubMed databases identified 182 articles. Through reviewing of the abstracts and references lists, 58 relevant articles were identified. The specific selection criteria were applied, and serial publications of papers reporting accumulating number of participants or increased length of follow-up were excluded with only the most recent and definitive update from each institution or the paper that fulfilled the specified endpoints of this review being included for appraisal and data extraction. In total, 28 articles were critically evaluated and tabulated (Table 1). The level of evidence from these studies was low (all level III). They comprised of retrospective observational studies. The 28 articles arose from institutions in the USA (n = 7), Europe (n = 11), and Asia (n = 10). In total, 1,458 patients were evaluated.

Treatment Criteria

In selecting patients for treatment, 21 studies13–33 reported the mode of investigations performed. This include computed tomography scans in all 21 institutions (100%), magnetic resonance imaging or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in 12 institutions (57%), and angiography in nine institutions (43%). After treatment investigations, all studies (n = 28) reported patients with pancreatic head tumors (100%), 12 studies (43%) included patients with pancreatic body tumors, and seven studies (25%) included patients with pancreatic tail tumors.

The priori basis of selecting patients for extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection and reconstruction was reported in 21 studies (75%).13–22,24,26–29,31,32,34–37 Among which, vein thrombosis was a reported contraindication to surgery in 13 of 21 studies (62%), and arterial involvement was a reported contraindication to surgery in 15 of 21 studies (71%) (Table 1).

Procedure of Extended Pancreaticoduodenectomy with Vascular Resection and Reconstruction

All 28 studies undertook resection of superior mesenteric-portal vein. Five of 28 studies (18%)21,22,30,35,37 undertook resection of the celiac axis, six studies (21%)21,22,30,31,35,37 undertook resection of the hepatic artery, and five studies (18%)21,22,30,31,35 undertook resection of the superior mesenteric artery. One thousand, one hundred thirty-six patients (78%) underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. In undertaking vascular resection, 23 of 28 studies (82%)13–15,17–27,29–32,34–36,38,39 examined the resected vessel histologically. The histopathological analysis of the resected vessel indentified true neoplastic invasion in between 21% and 100% of cases with a median of 63%. The most common techniques of reconstruction after vascular resection include end–end anastomosis and graft reconstruction (using either an autologous vein graft or synthetic graft). The surgical procedure resulted in estimated blood loss that was reported in 18 of 28 studies (64%)15–20,22–24,26–29,32,33,37,40 ranging between 700 and 3,083 mL with a median of 1,494 mL (Table 2).

Postoperative Complications and Mortality Outcome

The mortality rate was reported in 27 of 28 studies (96%)14–40 and ranged from 0% to 17% with a median of 4%. The median rate of bleeding was 4% (range, 0% to 16%), rate of collection or abscess was 5% (range, 0% to 29%), rates of vascular thrombosis was 0% (range, 0% to 4%), rate of pancreatic fistula was 6% (range, 0% to 18%), rate of biliary leak was 0% (range, 0% to 16%), rate of pancreatic duct leak was 1% (range, 0% to 17%), and the reoperation rate was 9% (range, 0% to 25%). The median average length of hospital stay was 17 days (range, 11 to 69 days; Table 3).

Treatment Efficacy

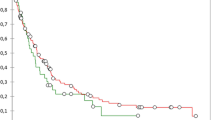

Twenty-one of 28 studies (75%)13–19,22–25,27–29,31–34,36–40 reported margin status after extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection. Microscopically clear margin (R0) rates ranged from 14% to 100% with a median of 75%. The rate of margins that were grossly clear but microscopically involved (R1) ranged from 0% to 86% with a median of 25%. The median survival in studies reporting vein resection was 13 months (range, 5 to 23 months), with a median 1-year survival rate of 56% (range, 23% to 88%), median 3-year survival rate of 18% (range, 0% to 49%), and median 5-year survival rate of 12% (range, 0% to 25%). The median survival in studies reporting both vein and artery resection was 18 months (range, 3 to 20 months), with a median 1-year survival rate of 65% (range, 26% to 83%), median 3-year survival rate of 13% (range, 0% to 35%), and median 5-year survival rate of 0% (range, 0% to 20%; Table 4).

Outcomes in High-Volume Centers

Sixteen high-volume centers each reporting more than 20 pancreatectomy procedures per annum were identified, and their outcomes were reported separately in Table 5.14,16,18,22,23,25,27–33,36,37,40 In these centers, 10 of 16 studies (63%)14,16,18,22,25,27,28,31,36,40 reported a comparison of survival between patients who underwent extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection versus standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Nine of 10 (90%) studies reported statistically similar survival outcomes.14,16,18,22,25,28,31,36,40 The median survival of patients undergoing extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection was 15 months (range, 9 to 23 months).

In the analysis of prognostic factors after extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection, 11 studies14,16,18,22,27–29,31,32,36,37 reported univariate analysis of clinicopathological factors associated with survival. There were no consistent adverse factors associated with a poor survival. Venous tumor infiltration was commonly identified as having no effect on survival. Seven studies14,16,23,25,28,36,40 reporting a combined univariate analysis of patients undergoing both extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy reported that undergoing vascular resection was not associated with a poorer survival (Table 5).

Discussion

Surgery remains the only curative option for pancreatic cancer. It is commonly performed in selected patients with localized disease of the pancreas (T1 and T2 tumors). In the past, this procedure has been morbid with mortality rates of up to 25% in early series. However, improved techniques and training in the last decade have led to improved operative results and long-term survival outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer following pancreaticoduodenectomy, hence leading to a renewed interest in the surgical oncologic management of this disease.41 Through cumulated experience in the operative and perioperative management of patients undergoing pancreatic surgery, the criteria for resectability has gradually expanded. Extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection has been offered in various institutions to treat patients with tumors that has involved or invaded the adjacent blood vessels. This would represent a large number of patients as the siting of the pancreas and its relationship with the adjacent critical blood vessels make these structures a common site of tumor involvement through direct invasion. Performing vascular resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy would often be the goal of a surgeon who seeks to attempt a total resection. With now established safety, it appears that such a procedure may be considered given the grim outlook of patients with unresectable tumors even after treatment. It is unlikely that the conduct of a randomized trial to determine if extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection versus a comparator group such as a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy with adjuvant chemoradiation to treat the remnant tumor burden or a treatment of chemoradiation alone would be feasible given the known prognosis of incomplete resections. Therefore, a systematic review that critically examines the important aspects of this procedure, namely the safety, survival outcomes in relation to the resection of involved vessels in the context of expert centers, would be invaluable in achieving consensus and acceptance of this procedure.

Results from this review show that vascular resection is commonly performed in patients with venous only involvement. The median mortality rate of 4% of extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection, the similar rates of postoperative complications that occur, and a median average length of hospital stay of 17 days suggest that the perioperative outcome is similar to that of a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. In 16 centers which were classified as high-volume centers where at least 20 pancreatectomy procedures were performed per annum, the median survival of patients undergoing extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection was 15 months. These survival results when compared with their independent cohorts who underwent standard pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures were not different. Studies that analyzed prognostic factors showed that undergoing vascular resection was not associated with a poorer survival. A 75% chance of a clear margin (R0) rate after this radical procedure further supports the rationale of undertaking extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection when total resection of a locally advanced tumor is achievable.

Pancreatic cancer involvement of key vessels on preoperative imaging may not necessarily imply vascular invasion of the tumor into macroscopic vessels. It is not easy to determine definitively based on imaging the texture of the tumor and its associated adherence. Intraoperatively, the involvement or encasement that is present may occur as part of a peritumoral inflammatory reaction of the peripancreatic stromal tissue that leads to fibrotic change that may mimic tumor.42 However, even in instances when there is true tumor involvement after histopathological examination of the resected vessel, venous tumor infiltration was not identified to affect survival. This may lead to a proposal for a change in surgical approach in patients with venous involvement on preoperative imaging scans and when examined at laparotomy. An en bloc vascular resection after adequate mobilization of proximal and distal ends to facilitate an end to end or graft reconstruction may be performed instead of an attempted dissection along the superior mesenteric-portal vein that risk injuring the thin and friable venous intima.

Clearly, the key of a successful surgical treatment arises from appropriate patient selection that preoperatively determines the extent of venous or arterial involvement, nodal disease, and absence of distant metastatic sites together with a patient’s overall performance status and fitness for surgery. The majority of studies (71%) performing vascular resections reported arterial involvement as a contraindication to surgery. However, in centers such as that reported by Martin et al.,22 Yekebas et al.,31 and Stitzenberg et al.,37 with expertise in en bloc resection of the hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery, or even the celiac trunk itself, this may be performed with equivalent survival outcomes with median survival of 18, 20, and 17 months reported, respectively. In contrast, less experienced centers who have undertaken this procedure have shown poorer outcomes following arterial resection than after venous only resection.35

Improved survival in pancreatic cancer has evolved from standard pancreatectomy to extended pancreatectomy in selected patients in the setting of an expert referral center through increasing the resectability rates in borderline resectable patients after careful selection and achieving high R0 resection rates. Vascular resection and reconstruction of the adjacent vein and in some highly selected instances, the arteries appear to be feasible, without compromising R0 resection rates, and allow for patients with “unresectable tumors” to undergo a curative procedure for a chance at having long term survival. Presently, further surgical advancement to resect pancreatic cancer in patients with nonlocalized disease is unlikely to be beneficial. To improve the survival from now, the search for an effective systemic chemotherapeutic agent and testing of these agents in trials of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant therapy with radiotherapy as well as with immunotherapy is necessary to complement the oncological benefit achieved after a complete surgical resection.

References

Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:267–277.

Ueno H, Kosuge T, Matsuyama Y, et al. A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;101:908–915.

Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group.[see comment]. Ann Surg 1999;230:776–782; discussion 782–774.

Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncology 2005;23:3509–3516.

Chauffert B, Mornex F, Bonnetain F, et al. Phase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2000-01 FFCD/SFRO study. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1592–1599.

Fortner JG. Regional resection of cancer of the pancreas: a new surgical approach. Surgery 1973;73:307–320.

Michalski CW, Kleeff J, Wente MN, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of standard and extended lymphadenectomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2007;94:265–273.

Farnell MB, Pearson RK, Sarr MG, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing standard pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2005;138:618–628; discussion 628–630.

House MG, Gonen M, Jarnagin WR, et al. Prognostic significance of pathologic nodal status in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. J Gastroint Surg 2007;11:1549–1555.

Merchant NB, Rymer J, Koehler EAS, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiation therapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: who really benefits? J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:829–838; discussion 838–841.

Siriwardana HPP, Siriwardena AK. Systematic review of outcome of synchronous portal-superior mesenteric vein resection during pancreatectomy for cancer.[see comment]. Br J Surg 2006;93:662–673.

Ramacciato G, Mercantini P, Petrucciani N, Giaccaglia V, Nigri G, Ravaioli M, Cescon M, Cucchetti A, Del Gaudio M. Does portal-superior mesenteric vein invasion still indicate irresectability for pancreatic carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16(4):817–825

Al-Haddad M, Martin JK, Nguyen J, et al. Vascular resection and reconstruction for pancreatic malignancy: a single center survival study. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1168–1174.

Bachellier P, Nakano H, Oussoultzoglou PD, et al. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal venous resection safe and worthwhile? Am J Surg 2001;182:120–129.

Capussotti L, Massucco P, Ribero D, et al. Extended lymphadenectomy and vein resection for pancreatic head cancer: outcomes and implications for therapy. Arch Surg 2003;138:1316–1322.

Carrere N, Sauvanet A, Goere D, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal vein resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. World J Surg 2006;30:1526–1535.

Howard TJ, Villanustre N, Moore SA, et al. Efficacy of venous reconstruction in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:1089–1095.

Illuminati G, Carboni F, Lorusso R, et al. Results of a pancreatectomy with a limited venous resection for pancreatic cancer. Surg Today 2008;38:517–523.

Kaneoka Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: prognostic value of the length of venous resection. Surgery 2009;145:417–425.

Koniaris LG, Staveley-O’Carroll KF, Zeh HJ, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the presence of superior mesenteric venous obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:915–921.

Li B, Chen FZ, Ge XH, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy with vascular reconstruction in treating carcinoma of the pancreatic head. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2004;3:612–615.

Martin RCG 2nd, Scoggins CR, Egnatashvili V, et al. Arterial and venous resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: operative and long-term outcomes. Arch Surg 2009;144:154–159.

Muller SA, Hartel M, Mehrabi A, et al. Vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery: survival determinants. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:784–792.

Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with En Bloc Portal Vein Resection for pancreatic carcinoma with suspected portal vein involvement. World J Surg 2004;28:602–608.

Riediger H, Makowiec F, Fischer E, et al. Postoperative morbidity and long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy with superior mesenterico-portal vein resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1106–1115.

Shibata C, Kobari M, Tsuchiya T, et al. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection for adenocarcinoma in pancreas. World J Surg 2001;25:1002–1005.

Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T. Clinical implications of combined portal vein resection as a palliative procedure in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1569–1578.

Tseng JF, Raut CP, Lee JE, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection: margin status and survival duration. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:935–949; discussion 949–950.

van Geenen RC, ten Kate FJ, de Wit LT, et al. Segmental resection and wedge excision of the portal or superior mesenteric vein during pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery 2001;129:158–163.

Wang C, Wu H, Xiong J, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for local advanced pancreatic head cancer: a single center retrospective study. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:2183–2190.

Yekebas EF, Bogoevski D, Cataldegirmen G, et al. En bloc vascular resection for locally advanced pancreatic malignancies infiltrating major blood vessels: perioperative outcome and long-term survival in 136 patients. Ann Surg 2008;247:300–309.

Zhou GW, Wu WD, Xiao WD, et al. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection: report of 32 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2005;4:130–134.

Jain S, Sacchi M, Vrachnos P, Lygidakis NJ. Carcinoma of the pancreas with portal vein involvement - our experience with a modified technique of resection. Hepatogastroenterology 2005;52:1596–1600.

Kawada M, Kondo S, Okushiba S, et al. Reevaluation of the indications for radical pancreatectomy to treat pancreatic carcinoma: is portal vein infiltration a contraindication? Surg Today 2002;32:598–601.

Nakao A, Takeda S, Inoue S, et al. Indications and techniques of extended resection for pancreatic cancer. World J Surg 2006;30:976–982; discussion 983–974.

Roder JD, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Carcinoma of the periampullary region: who benefits from portal vein resection? Am J Surg 1996;171:170–174; discussion 174–175.

Stitzenberg KB, Watson JC, Roberts A, et al. Survival after pancreatectomy with major arterial resection and reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1399–1406.

Launois B, Stasik C, Bardaxoglou E, et al. Who benefits from portal vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer? World J Surg 1999;23:926–929.

Nakagohri T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, et al. Survival benefits of portal vein resection for pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg 2003;186:149–153.

Harrison LE, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Isolated portal vein involvement in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A contraindication for resection? Ann Surg 1996;224:342–347; discussion 347–349.

Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg 2006;244:10–15.

Wilentz RE, Hruban RH. Pathology of cancer of the pancreas. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 1998;7:43–65.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding

Dr. Terence C. Chua is a surgical oncology research scholar funded by the St George Medical Research Foundation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chua, T.C., Saxena, A. Extended Pancreaticoduodenectomy with Vascular Resection for Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg 14, 1442–1452 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1129-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1129-7