Abstract

In pancreatic cancer patients, survival and palliation of symptoms should be balanced with social and functional impairment, and for this reason, health-related quality of life measurements could play an important role in the decision-making process. The aim of this work was to evaluate the quality of life and survival in 92 patients with different stages of pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical and/or medical interventions. Patients were evaluated with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy questionnaires at diagnosis and follow-up (3 and 6 months). At diagnosis, 28 patients (30.5%) had localized disease (group 1) and underwent surgical resection, 34 (37%) had locally advanced (group 2), and 30 (32.5%) metastatic disease (Group 3). Improvement in quality of life was found in group 1, while in group 3, it decreased at follow-up (p = 0.03). No changes in quality of life in group 2 were found. Chemotherapy/chemoradiation seems not to significantly modify quality of life in groups 2 and 3. Median survival time for the entire cohort was 9.8 months (range, 1–24). One-year survival was 74%, 30%, and 16% for groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively (p = 0.001). Pancreatic cancer prognosis is still dismal. In addition to long-term survival benefits, surgery impacts favorably quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer remains the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA. Of the 32,180 patients diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 2006, the great majority will die within 2 years from initial diagnosis.1 Less than 20% of the patients are candidates for surgical resection, which remains the only treatment offering the possibility of long-term survival, even if this is only 10% to 25%.2–4 The remaining patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease, and for them, chemotherapy or chemoradiation represent the current standard of care with the aim of improving survival.5–7

During the course of disease, 70% to 80% of patients with pancreatic head tumors develop obstructive jaundice, and 10% to 20% duodenal obstruction.8–10 Many also will manifest pain, which is probably the most disturbing and incapacitating symptom in advanced pancreatic cancer.11 Adequate palliation of biliary and duodenal obstruction, as well as of pain, is one of the goals in the treatment of these patients. However, optimal methods of palliation remain controversial in terms of patient benefit perception and durability.12–15 Many studies have compared different treatments and palliative procedures in different stages of the disease, but few have considered these issues among the entire spectrum of pancreatic cancer patients.4,16

To assess the value of a treatment, physicians routinely use “physician-centered” objective outcomes, such as disease recurrence, complications, treatment toxicity, or survival, but infrequently consider patients’ perception and quality of life.17 Health-related quality of life (HQOL) seeks to measure the impact of disease process on physical, psychological, and social aspects of the person’s life and feeling of well-being,18–20 and recently, has become an important subject in pancreatic cancer care, with the aim of measuring the impact of different interventions on patients’ health and life.18,21–24 It has become clear that in a disease-like pancreatic cancer, in which patients have a short life expectancy, improvements in survival and treatment-related complications must be carefully balanced against HQOL outcomes to define better approaches while considering patients’ personal needs.

The aim of this prospective study is to analyze the effects of therapeutic and palliative treatments on health outcomes and HQOL in a contemporary cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, 105 patients with histologically proven ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, treated at Massachusetts General Hospital between September 2004 and January 2006, were enrolled in this study after obtaining informed consent. Demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory and radiologic findings, type of surgery, postoperative morbidity and mortality, pathology, neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments, type of palliation, disease recurrence, and number of readmissions were recorded. Patients with adenocarcinoma arising in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas were excluded.

Patients were classified in three clinical stages: apparently localized cancer (group 1), locally advanced (group 2), and metastatic (group 3). Localized cancer permitted resection. Locally advanced cancer was defined as extension of the neoplasm outside the pancreas with major vascular encasement or other features precluding potentially curative resection. Local recurrence was defined as recurrent retroperitoneal mass or regional lymph nodes in patients who had undergone pancreatic resection with curative intent. Metastases were defined as a relapse of disease in the peritoneal cavity or at any distant site.

Follow-up data was obtained through direct contact with patients’ oncologists, primary care physicians, and families.

Quality of Life Assessment

To assess health-related quality of life, the fourth version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) and the hepatobiliary and pancreatic specific module (FACT-Hep) were used. The FACT-G is a 27-item self-report instrument that assesses four different dimensions of quality of life: physical (seven items), social (seven items), emotional (six items), and functional (seven items). The specific subscale for hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases (FACT-Hep) has 18 additional items. Patients responded to HQOL questions on a five-point Liker-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). FACT-G and FACT-Hep have been previously validated in cancer populations.25–27

From these two questionnaires, three scores were obtained: the FACT-G score, which is the sum of the four subscales; the FACT-Hep, which is the sum of the FACT-G and the disease-specific module (FACT-Hep), and the Trial Outcome Index (TOI), which is the sum of the physical, functional and disease-specific module. The TOI has been demonstrated to be a sensitive indicator of clinical outcome.27

Each questionnaire was applied at diagnosis (baseline) and sent by mail after 3 and 6 months from the initial diagnosis.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. We performed paired and unpaired t student and χ 2 tests when comparing nominal and categorical variables, respectively. In the case of a nonparametric distribution, a Mann–Whitney U was done. One-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis was performed for multiple comparisons with normal distribution, and the probability was adjusted by Tukey’s correction. A 5% of significance was accepted. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan–Meier method.

HQOL scores were analyzed from a statistical and clinical significance viewpoint. For the statistical analysis, due to a lack of complete sets of questionnaires in some patients, a cross-sectional analysis was done, and all patients who provided HQOL questionnaires at baseline were compared with all those provided follow-up HQOL data. Thus, scores available at 3- and 6-month follow-up were grouped together as “follow-up scores.” For the purpose of the clinical analysis, scores available at 3- and 6-month were considered separately. HQOL scores were compared among the three groups at baseline and follow-up and within each group (baseline versus follow-up scores). Moreover, HQOL scores were compared in the entire cohort (n = 92) or in groups 2 and 3 patients (n = 64) to evaluate differences in the following independent variables: age, resection, CA 19.9 level, adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatment in the entire cohort, and need for stents, chemotherapy/chemoradiation, and celiac block in groups 2 and 3.

Clinical significance was determined using the meaningful important difference (MID). MID is defined as “the smallest difference in score in the outcome of interest that informed patients perceive as important, either beneficial or harmful, and that would lead the patient or clinician to consider a change in the management”.27,28 MIDs measure the clinical relevant changes in HQOL perception derived from a treatment or the disease itself. To estimate MID, the mean of all HQOL scores (FACT-G, FACT-Hep, TOI) were first assessed, and subsequently, differences between mean HQOL scores at baseline and at 3- and 6-months were evaluated. Differences in mean HQOL scores considered clinically significant (MIDs) were as follows: 8–9 for FACT-Hep, 7–8 for FTOI and 6–7 for FACT G.27

Results

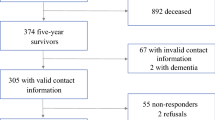

Of the 102 patients initially enrolled, ten with no complete HQOL questionnaires at baseline were excluded, and therefore, final analysis was performed in 92 patients (46 women and 46 men; mean age ± SD of 66 ± 10 years; range, 42–88).

At diagnosis, 28 patients (30.5%) had localized disease (group 1), 34 (37%) had locally advanced disease (group 2), and 30 (32.5%) had metastatic disease (group 3).

Demographics

Demographic characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 1. There were no differences among the three groups with regard to age, sex, and tumor location. Jaundice was the most common presenting symptom in group 1 (86% of patients), while its frequency was lower in groups 2 and 3 (21% and 14%, respectively; P = 0.0001). Abdominal pain and weight loss were more likely to be associated with locally advanced or metastatic disease. As expected, median CA 19.9 was significantly higher in patients with metastatic disease.

Diagnostic and Palliative Procedures

Table 2 shows diagnostic and palliative procedures as well as data regarding hospital stay and readmissions. All the patients underwent at least one computed tomography (CT) scan. The mean number of CTs performed per patient was significantly greater in those with localized disease. The number of endoscopic ultrasounds (EUS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopically placed biliary stents was greater in group 2 patients, but the difference was significant only when comparing EUS between groups 2 and 3 (83% versus 53%, P = 0.01). Only three patients (10%) in groups 3 and two (6%) in group 2 required a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage during their clinical course. No patient in group 1 underwent percutaneous or intraoperative celiac block compared to 14 patients (41%) in group 2 and 6 (20%) in group 3. Enteral stents were used to palliate malignant duodenal obstruction in six patients (18%) in group 2 and in two patients (7%) in group 3. Four patients in group 2 and one in group 3 had both enteral and biliary stents.

The overall mean hospital stay and the number of readmissions were significantly shorter in patients with metastatic disease. Fifty-six percent of patients with locally advanced disease required two or more readmissions, compared to 36% in group 1 and 27% in group 3. There were no differences between groups 2 and 3 in the number of surgical palliative procedures. Five patients with locally advanced disease received intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in association with palliative surgery.

Treatment

Twenty-nine patients underwent pancreatic resection with curative intent. Of these, 28 patients had localized disease at diagnosis, and one patient had locally advanced disease and underwent resection after chemoradiation. Table 3 shows the intraoperative, postoperative, and pathologic features of these patients. Overall morbidity was 24%, mortality was nil, and no patient required surgical re-exploration.

Of the 29 resected patients, four underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation (three patients of group 1 and one of group 2), and 21 underwent adjuvant chemoradiation. Of these patients, ten received gemcitabine, and the remaining, 5-fluorouracil. Four patients declined further treatment.

With regard to the 34 patients in group 2, 18 (53%) underwent chemoradiation (including the five who received also IORT), 11 (32%) chemotherapy alone, and five (15%) refused any treatment or were considered unsuitable for chemotherapy or chemoradiation because of major comorbidities. In group 3 (n = 30), 24 patients (80%) underwent chemotherapy, three (10%) chemoradiation, and three (10%) refused treatment. In patients who underwent chemotherapy alone, gemcitabine was administrated as single agent in 14 cases, and in association with new agents, as part of clinical trials in the remaining ten patients.

Survival

All but two patients were followed until death or at least 12 months. The median survival for the entire cohort was 9.8 months (mean ± SD, 9.5 ± 6; range, 1–24). Figure 1a shows survival of the entire cohort, and Fig. 1b the survival of the three different groups. One- and 2-year survival for the entire cohort was 39% and 23%. One-year survival was 74%, 30%, and 16% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P = 0.001). The median survival for group 3 was 5.8 months, for group 2 8.6 months, and for group 1, it has not been reached. With regard to the 29 patients who underwent surgical resection, 12 of them developed tumor recurrence at a median time of 7 months from operation. Sites of recurrence were distant metastases in eight patients and locoregional in four. Ten patients died of disease while two remain alive with disease. The remaining 17 patients are alive with no evidence of disease at a median of 14 months (range, 12–23).

a Kaplan–Meier overall survival curve in 92 patients with pancreatic cancer. One- and 2-year survival was 39 and 23 months. b Kaplan–Meier survival curves in patients with localized (group 1, n = 28), locally advanced (group 2, n = 34), and metastatic pancreatic cancer (group 3, n = 30) at initial presentation. One-year survival was 74%, 30%, and 16% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P = 0.001).

The mean survival for the five patients who underwent IORT was 10.6 ± 6.2 months. Two of these patients died for tumor progression after 8.8 and 8.6 months, while the remaining patients are alive with stable disease.

Quality of Life

Baseline questionnaires were completed in 92 patients (100%). The rate of completed questionnaires decreased to 56% at 3 months and to 48% at 6 months. Excluding dead patients, the rate of completed questionnaires was 63% at 3 months and 59% at 6 months.

Table 4 shows HQOL scores at baseline and during follow-up. At baseline, no statistical differences were found in the HQOL scores among the three groups, while during follow-up, patients in group 1 had higher HQOL scores compared to groups 2 and 3. Comparisons within each group showed an improvement of HQOL scores from baseline to follow-up in groups 1 and 2, and a worsening of all scores in group 3.

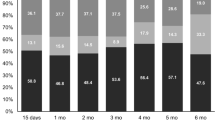

Clinically meaningful changes (MIDs) from baseline to 3- and 6-months were found in groups 1 and 3 but not in group 2 (Fig. 2). The MIDs in group 1 were toward improvement and in group 3 toward deterioration.

Since HQOL scores at baseline were homogeneous among the three groups, we performed statistical analysis of HQOL scores considering different variables in the entire cohort (n = 92; Table 5). Patients who underwent resection (n = 29) had significantly higher HQOL scores at follow-up compared to nonresected ones (n = 63; P = 0.001). Patients with CA 19–9 values above 200 U/l (n = 46) had lower HQOL scores both at baseline (P = 0.01) and during follow-up (P = 0.04). There were no statistically significant differences in HQOL scores regarding age (cut-off, 60 years) and chemotherapy/chemoradiation both at baseline and during follow-up.

Patients in groups 2 and 3 who required biliary or enteral stents, celiac block, and chemoradiation/chemotherapy alone were analyzed from a clinical viewpoint (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). Patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease who underwent stent placement had a decrease in HQOL scores at 3 months but a clinically significant recovery at 6 months, whereas patients without stents did not have significant changes in HQOL mean scores at 3 and 6 months (Fig. 3). Patients who underwent chemoradiation showed no significant differences in HQOL scores at 3 and 6 months, whereas those who received chemotherapy alone presented a significant decrease in HQOL score at 3 months with a nonsignificant improvement at 6 months (Fig. 4). Patients who underwent celiac block had a decrease in HQOL score at 3 months and a significant recovery at 6 months. No changes in quality of life were found in patients without celiac block from baseline to follow-up (Fig. 5).

The statistical analysis of these variables in groups 2 and 3 patients was not significant.

Discussion

“The outlook in carcinoma of the pancreas continues to be grim.” With this peremptory sentence, Morrow and colleagues summarized the 1975–1980 experience of Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center in treating 231 patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas.29 They reported a resecability rate of 16.9% and a median survival of 18 months for patients who underwent resection, and of only 4 months for those who had surgical bypass. Over the last 25 years, many efforts have focused on improving outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients. Morbidity and mortality after pancreatic surgery have decreased markedly, chemotherapy and chemoradiation regimens have been developed, and 5-year survival rates of up to 25% have been reported in resected patients.2,16,30–35

While many studies have evaluated specific stages of pancreatic cancer, few have reported data on the entire spectrum of disease, considering treatments, palliative procedures, and outcomes.16 The present study specifically addresses this point to give the reader a “snapshot” of pancreatic cancer treatment at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, the picture that emerges continues to be as grim as that described by Morrow 25 years ago. Our data shows that, despite chemotherapy and chemoradiation, the median survival is only 5.8 months for patients with metastatic disease and 8.6 months for those with locally advanced cancers, these two groups together constituting two thirds of the pancreatic cancer population seen in a cancer center. The one-year survival rate for the entire cohort was only 39%, and 58% of these are patients who underwent resection. Our survival rates did not significantly differ from those generally reported in the literature.4–7,30–35 Moreover, we considered a consecutive series of patients newly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, not a selected population with favorable prognostic factors in which better survival rates can be achieved.16,24,33

Surgery remains the only possibility of long-term survival for patients with pancreatic cancer, but the great majority of them are not amenable to resection even after neoadjuvant treatments.16,36 In this series, 53% of group 2 patients underwent chemoradiation, but only in one case was sufficient “downstaging” obtained to allow subsequent surgical resection. These data underscore that palliation rather than curative treatment still remains the most relevant goal in the great majority of patients with pancreatic cancer.

In addition to evaluating treatment and survival, our study assessed longitudinal changes in HQOL, using validated instruments administrated at diagnosis and during follow-up. Physicians aiming to keep patients comfortable and free of symptoms must evaluate the impact of these interventions on patients’ quality of life.17 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that considers HQOL in patients with the full spectrum of localized, locally advanced, and metastatic pancreatic cancer.

The instruments used for HQOL evaluation in pancreatobiliary diseases range from visual analogue scales to generic HQOL (FACT-G or EORTC QLQ-C30) or disease-specific (FACT-Hep) questionnaires.18,23,24,37 We used both the FACT-G and FACT-Hep questionnaires, which have an excellent test–retest reliability, and high internal consistency are easy to complete and have been validated for patients with pancreatobiliary cancers.23–26 In addition to the general and disease-specific scores we also evaluated the F-TOI, a functional index that is a sensitive indicator of clinical outcome.27

In the present study, data were analyzed to look for both statistical and clinical significance, which account for two different perspectives in HQOL interpretation.28,38 The purpose of statistical analysis is to quantify the importance of differences in a cohort of patients (population), and the sample sizes inevitably affect statistical power. However, statistically significant changes in a general population setting may not be meaningful in the context of single or few individuals. Clinical significance focuses upon detecting changes that are important in the patient’s perspective and therefore relevant in the management of individual patients. MIDs were used to define clinical significance in this study.27

Interestingly, our data shows no statistical or clinical significant differences in HQOL scores at baseline among the three groups, which were also homogeneous for age, sex, and site of tumor. Only patients with localized disease who underwent surgical resection (group 1) had a subsequent improvement in quality of life: Scores on almost all HQOL scales improved during follow-up after surgical resection. In contrast, a decrease of all the scores was evident in group 3, while a slight increase was found in group 2 (Table 4).

It is difficult to compare HQOL results among different studies because of differences in instruments, methodology, and patient population.37,39 In some, various periampullary tumors or pancreatic diseases were considered,18,21 or HQOL was not assessed longitudinally but only after the therapeutic intervention.23 Not surprising therefore, our results differ from those previously reported in the literature. Schniewind et al.37 in a prospective study evaluating HQOL in a group of 91 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer, showed a large decrease in most HQOL scales after surgery, followed by a slow recovery to preoperative levels. A similar trend was found by Nieveen van Dijkum et al.21 who compared pancreaticoduodenectomy versus biliary and duodenal bypass for pancreatic and periampullary carcinomas. Farnell et al.24 comparing pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without extended lymphadenectomy in pancreatic cancer, found a decrease in most of HQOL scores from baseline to 4 months after surgery in both groups.

In contrast, we found an improvement of HQOL scores from baseline to follow-up only after surgical resection. This difference was clinically but not statistically significant despite pancreatic surgical resections being extensive procedures associated with potential major complications. The difference between group 1 versus groups 2 and 3 certainly depend upon the differences in cancer stage and are influenced by the curative potential of surgical resection and the rapid evolution of the disease in unresected patients. It is nonetheless remarkable that HQOL scores improved during follow-up in group 1 patients, even though 73% of them underwent adjuvant chemoradiation.

A common methodological problem of HQOL studies is missing data, which may lead to bias.21,23,37 Specifically, missing data can result in overestimation of HQOL since very sick or dying patients are less likely to complete the questionnaires. In our study, this defect might be more prevalent in groups 2 and 3, but it is unlikely that overestimation affected group 1 because the majority of patients were alive with no recurrent disease 3 and 6 months after surgery.

In patients with advanced disease, we evaluated the impact of different palliative procedures and treatment on HQOL. In patients who develop jaundice and/or gastrointestinal obstruction but who are judged to be unresectable, endoscopic procedures are our first choice for palliation, while surgical bypass is generally performed for tumors found to be unresectable at laparotomy. Several studies in assessing the feasibility and efficacy of endoscopic biliary and enteral stenting as an alternative to surgical bypasses have shown that stenting is associated with lower costs and better quality of life when compared to surgical bypass.10,12,13 In our cohort, patients who underwent stent placement had a decrease in HQOL at 3 months but a clinically significant improvement at 6 months, while there were no significant changes in patients who did not require or receive stents (Fig. 3).

Pain control is a major issue in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.11,15 Recently, Yan et al. and Wong et al. showed that,14,40 compared with standard analgesia, celiac block is associated with a significant but limited reduction of pain but does not improve either quality of life or survival. They concluded that celiac block should not replace standard pain control measures but should be used selectively as an adjunct. Pain relief based on systemic analgesics was successfully obtained in 59% of group 2 and 80% of group 3 patients. Patients who underwent celiac block had a decrease in HQOL at 3 months but a clinical significant improvement at 6 months, while no changes in HQOL were detected in the remaining patients (Fig. 5).

Chemotherapy and chemoradiation did not seem to impact HQOL differently in patients with locally advanced and metastatic disease. At 3 months, worse scores were found in the chemotherapy group, although this can be explained by the fact that chemotherapy was preferentially performed in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer (Fig. 4).

Conclusion

In conclusion, because the rate of cure for pancreatic cancer continues to be very low, palliation of symptoms remains the more attainable goal for most cases. This study shows that there is a good overall impact of surgical and medical interventions on the quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer. Despite potential perioperative and long-term complications, pancreatic resection improves quality of life of those with localized disease. Chemoradiation and chemotherapy do not negatively impact the quality of life in patients with locally advanced disease, but chemotherapy in patients with metastatic disease is associated with a significant decrease in quality of life during follow-up, due either to chemotherapy, the progression of the cancer, or both.

References

Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics, 2005 CA. Cancer J Clin 2005;55:10–30.

Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Hruban RH. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg 2002;236:355–366.

Ferrone CR, Finkelstein DM, Thayer SP, Muzikansky A, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Perioperative CA19-9 levels can predict stage and survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2897–2902.

Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, Winchester DP. Pancreatic caner: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the national cancer database. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:1–7.

Talamonti MS, Small W, Mulcahy MF, Wayne JD, Attaluri V, Coletti LM, Zalupski MM, Hoffman JP, Freedman GM, Kinsella TJ, Philip PA, McGrinn CJ. A multi-institutional phase II trial of preoperative full-dose gemcitabine and concurrent radiation for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:150–158.

Yip D, Karapetis C, Strickland A, Steer CB, Goldstein D. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for inoperable advanced pancreatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;19:CD00093.

Ko AH, Dito E, Schillinger B, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Phase III study of fixed dose rate gemcitabine with cisplatin for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:379–385.

Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA. Palliation. Surgical and otherwise. Cancer 1996;78:605–614.

Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1999;230:322–328.

Mortenson MM, Ho HS, Bold RJ. An analysis of cost and clinical outcome in palliation for advanced pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg 2005;190:406–411.

Labori KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Wester T, Buanes T, Loge JH. Symptom profiles and palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer 2006;14:1126–1133.

Artifon EL, Sakai P, Cunha JE, Dupont A, Filho FM, Hondo FY, Ishioka S, Raju GS. Surgery or endoscopy for palliation of biliary obstruction due to metastatic pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2031–2037.

Maire F, Hammel P, Ponsot P, Aubert A, O’Toole D, Hentic O, Levy P, Ruszniewski P. Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:735–742.

Yan BM, Myers RP. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for pain control in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:430–438.

Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Kaufman HS, Yeo CJ, Pitt HA, Sauter PK. Chemical splanchnicectomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1993;217:447–455.

Kuhlmann KF, de Castro SM, Wesseling JG, ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:549–558.

Velanovich V. Using quality-of-life measurements in clinical practice. Surgery 2007;141:127–133.

Huang JJ, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Hruban RH, Cameron JL. Quality of life and outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2000;231:890–898.

Velanovich V. Using quality-of-life instruments to assess surgical outcomes. Surgery 1999;126:1–4.

Testa MA, Simonson D. Assessment of quality of life outcomes. N Engl J Med 1996;334:835–840.

Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Kuhlmann KF, Terwee CB, Obertop H, de Haes JC, Gouma DJ. Quality of life after curative or palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. Br J Surg 2005;92:471–477.

Billings BJ, Christein JD, Harmsen WS, Harrington JR, Chari ST, Que FG, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Sarr MG. Quality-of-life after total pancreatectomy: is it really that bad on long-term follow-up? J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:1059–1066.

Nguyen TC, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Campbell KA, Coleman J, Sauter K, Abrams RA, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ. Standard vs. radical pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: a prospective, randomized trial evaluating quality of life in pancreaticoduodenectomy survivors. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:1–9.

Farnell MB, Pearson RK, Sarr MG, DiMagno EP, Burgart LJ, Dahl TR, Foster N, Sargent DJ, Pancreas Cancer Working Group. A prospective randomized trial comparing standard pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2005;138:618–628.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–579.

Heffernan N, Cella DF, Webster K, Odom L, Martone M, Passik S, Bookbinder M, Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart L. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with hepatobiliary cancers: the functional assessment of cancer therapy—hepatobiliary questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2229–2239.

Steel JL, Eton DT, Cella D, Olek MC, Carr BI. Clinically meaningful differences in health-related quality of life in patients diagnosed with hepatobiliary carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2006;17:304–312.

Brożek JL, Guyatt HG, Schünemann HJ. How a well-grounded minimal important difference can enhance transparency of labeling claims and improve interpretation of a patient reported outcome measure. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:1–7.

Morrow M, Hilaris B, Brennan MF. Comparison of conventional surgical resection, radioactive implantation, and bypass procedure for exocrine carcinoma of the pancreas 1975–1980. Ann Surg 1984;199:1–5.

Trede M, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy: 118 consecutive resections without mortality. Ann Surg 1990;211:430–438.

Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Zahurak ML, Grochow LB, Abrams RA. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, outcomes. Ann Surg 1997;226:248–260.

Warshaw AL, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Pancreatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1992;326:455–465.

Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby TV, van Heerden JA. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg 1995;221:59–66.

Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas—616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastroint Surger 2000;4:567–579.

Riall TS, Nealon WH, Goodwin JS, Zhang D, Kuo YF, Townsend CM Jr, Freeman JL. Pancreatic cancer in the general population: improvements in survival over the last decade. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1212–1224.

Masucco P, Capussotti L, Magnino A, Sperti E, Gatti M, Muratore A, Sgotto E, Gabriele P, Aglietta M. Pancreatic resections after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced ductal adenocarcinoma: analysis of perioperative outcome and survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1201–1208.

Schniewind B, Bestmann B, Henne-Bruns D, Faendrich F, Kremer B, Kuechler T. Quality of life after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Br J Surg 2006;93:1099–1107.

Revicki D. FDA draft guidance and health-outcomes research. Lancet 2007;369:540–542.

Holzner B, Bode RK, Hahn EA, Cella D, Kopp M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Kemmler G. Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:3169–3177.

Wong GY, Schroeder DR, Carns PE, Wilson JL, Martin DP, Kinney MO, Mantilla CB, Warner DO. Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1092–1099.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Crippa was supported by the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (2007 Warren Fellowship Award). Dr. Domínguez was supported by the Fundacion Mexico en Harvard A.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Discussion

Thomas J. Howard, MD (Indianapolis, IN): This study is unique and what is unique about it is that they classified patients into three clinically relevant stages: Stage I is patients with localized cancer, stage II is patients with locally advanced cancer, and stage III is patients with metastatic cancer. They used a validated instrument to prospectively measure health-related quality of life, and they have an acceptable 59% response rate at 6 months. Their survival rates were as expected with a median survival of 9.8 months in the entire cohort and significant improvement in survival and health-related quality of life in those patients able to be resected. In contrast, patients with metastatic disease showed significant overall decline in health-related quality of life over time. These data fail to show the benefit of the use of chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in these patients, and I have several questions regarding this.

Question number one is, bias, in particular in studies with limited accrual, is a constant nemesis. I assume these patients represent a nonselected sampling of patients who were seen over this 16-month period at the MGH. Besides the 102 patients that were enrolled in your study, how many other patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma were treated at your institution who declined to be part of this enrollment?

My second question is that the FACT-G questionnaire, as you know, covers multiple health dimensions expressed by four subscale measurements: physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being. Did you find any differences either within or between groups in these subscales rather than just the overall scale to explain the findings that you report?

And my last question is could you speculate to the reasons, e.g., perhaps lack of a control group, underpowered, or the use of combination therapy, that you failed to identify any clinical benefit response to the use of systemic chemotherapy in your cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer?

Stefano Crippa, MD (Boston, MA): Thank you for reviewing our manuscript in advance and for these excellent questions. The first question is whether our patients represent no selected sampling of patients seen at Mass General Hospital during the study period. Well, every year, approximately 250 patients are referred to our hospital with the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and of these, 15% will undergo surgical resection. They come through different routes. Some are referred to the department of surgery, basically patients with localized disease, but many others with advanced pancreatic cancer and metastatic pancreatic cancer are referred to the department of oncology just for a second opinion or to the department of gastroenterology to have a stent placed. Many patients with advanced pancreatic cancer after the workup at Mass General will be followed out in other hospitals outside MGH. Therefore, we first tried to enroll in this study those patients who were actually treated at our institution to have more specific and detailed data regarding their treatment, the need for readmission, stents, and so on. And I have to say that a few patients declined to participate in the study.

The second question regards differences in subscale analysis among the three groups. Actually, we did not perform a subscale analysis. We analyzed only the FACT-G and the FACT-Hep models and the TOI, the trial outcome index, which is the sum of the functional, physical, and disease-specific models. Basically, the TOI gives you a better idea on the functional and physiological status of these patients, and we found an improvement of the TOI in patients with localized disease who underwent surgery, and this was a surprise for us. As expected, a decrease of the physiological and functional status in patients with advanced and, in particular, metastatic pancreatic cancer was found.

Finally, why our study failed to show a clinical benefit in patients with metastatic cancer. I agree with you that our study is certainly underpowered and we have a small sample size for each group. However, when we talk about patients with metastatic cancer and we look at the studies reported in the literature, we have to consider that, in many cases, the clinical benefit is measured in terms of a few weeks of improved survival, and I am not sure that this data is perceived as important, meaningful, or whether relevant by the single patient. Therefore, I think that, in this subset of patients, probably more detailed quality of life studies are needed.

Jennifer F. Tseng, MD (Boston, MA): This is a very nicely presented work from a great center. I have a comment and a question. It is a truism in those people who study quality of life that all quality of life is relative and that, in fact, when they have done studies of people that have either (a) won the lottery or (b) had an amputation, 12 months later, those people’s quality of life is equivalent. Therefore, my question to you is about the arbitrary nature of time points at 0, 3, and 6 months, et cetera. Did resection occur at 0 months, and so then, the first data point was three months after presumably any complications?

Dr. Crippa: Yes.

Dr. Tseng: Can you stratify by people that actually had surgical complications and people that did not have surgical complications?

Dr. Crippa: We did not do that because we had only 29 patients who had surgical resection, 28 with localized disease and one with locally advanced. Sorry, I cannot answer.

Dr. Tseng: And then if you follow those patients out, it will be interesting if you can present this in a year or two and see actually if those patients who underwent resections quality of life also diminishes, as one would expect, to the same level as those who did not undergo resection.

Dr. Crippa: For this study, we decided to evaluate quality of life at 3 and 6 months because this study was not focused only on patients with localized pancreatic cancer who had resection but also on patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Therefore, we scheduled the questionnaire time at 3 and 6 months because the median survival of metastatic patients is only 6 months. This is why we chose also this particular time.

O. Joe Hines, M.D. (Los Angeles, CA): I enjoyed your talk. Although pancreatic cancer is a grim disease, there are some lights of hope, so I don’t absolutely agree with your comparison to data that is from the 1970s and 1980s. There are some groups of patients that are having significantly improved survivals over the past 5 years, upwards of 35% to 40% 5-year survivals. My question for you really relates to the way you grouped your patients. You chose to group them by a staging system that is something that you developed for your study, and so, when someone looks at your paper and reads your data, it is going to be difficult for them to compare it to their own experience. I wonder why it is that you used this grouping. And secondly, have you had the chance to use something like the AJCC staging system to compare the groups so that others can understand the information in your paper a little better?

Dr. Crippa: We did not use the AJCC system. We basically decided to classify the patients according to their status at presentation. Therefore, these patients had a CT scan, endoscopic ultrasound, a detailed imaging workup, and they were classified in localized disease and locally advanced if there was an encasement of the vessel or an infiltration of the retroperitoneum without evidence of metastatic disease, and finally, patients with metastatic disease. We decided to do that because that was the presentation of our patients, and we did not do a stratification according to the AJCC system, which is a pathological and not a clinical classification.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crippa, S., Domínguez, I., Rodríguez, J.R. et al. Quality of Life in Pancreatic Cancer: Analysis by Stage and Treatment. J Gastrointest Surg 12, 783–794 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0391-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0391-9