Abstract

This study extends the current state of research on venture capital (VC) determinants by introducing a behavioral perspective. We focus on individuals’ risk perception and connect it to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of individualism and uncertainty avoidance. Individualism is related to overoptimism and uncertainty avoidance is related to overcaution, and hence affect the perception of risk. In a cross-country empirical analysis with 49 countries, we find that individualism is positively associated with VC activity, whereas uncertainty avoidance is negatively associated with VC activity. Our results are robust to controlling for other determinants as well as using other proxies of VC activity, other time periods, and subsamples of countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A number of recent studies show that behavioral finance is able to explain several empirical findings that traditional finance theory leaves unexplained (Baltussen2010). Behavioral finance aims at augmenting the understanding of financial markets by using insights from behavioral sciences like psychology and sociology. Our paper incorporates behavioral models into the area of venture capital (VC).

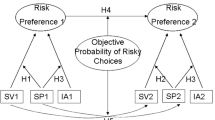

We examine the extent to which VC is impacted by behavioral biases leading to different perceptions of risk. Behavioral explanations discussed in this context refer to overoptimism and overcaution. In particular, we examine whether the availability of VC is induced in countries where investors and entrepreneurs are likely to exhibit these psychological biases. We focus on what psychologists refer to as “individualism” and “uncertainty avoidance”. We use the individualism and uncertainty avoidance indexes reported by Hofstede (2001) which have become widely accepted and used by many researchers in other business disciplines. We argue that individualism is likely to be correlated with overoptimism and uncertainty avoidance with overcaution.

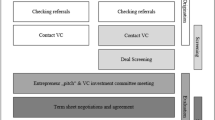

VC is investment in privately held, young growth companies with no or few intangible assets that is provided by professional investors (Lerner1994; Gompers and Lerner2001b). Investors usually purchase large equity stakes, use their control rights extensively, and provide entrepreneurs and their companies with funding, strategic advice, contacts, and reputation. The field of VC research has been attracting much interest, given its importance for the funding of young innovative firms (Barry et al.1990). Literature has argued that young growth companies feature a favorable setting for the promotion of innovation (Kortum and Lerner2000; Zingales2000). Innovations are vital for the long-term growth of any economy as they generate positive impulses that enhance the economic welfare (Gebhardt and Schmidt2002; Lerner and Gompers2002).

Previous research has well documented international differences in venture capital markets (Black and Gilson1998; Jeng and Wells2000; Bascha and Walz2001; Schwienbacher2002; Mayer et al.2005; Antonczyk et al.2008; Lerner et al.2009), which are both of size and substance. VC investments differ across countries in terms of investment activity, technological stage, sector and funding sources. Figure 1 illustrates the varying levels of VC availability across countries as reported in the World Economics Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2008–2009. The VC availability index evaluates answers to the question: “In your country, how easy is it for entrepreneurs with innovative but risky projects to find venture capital? (1 = impossible, 7 = very easy)”.

There is a growing body of work examining the factors influencing the development of VC markets internationally. Nevertheless, research in this field of VC is rather limited so far, as most studies have primarily focused on financial market properties like the number of initial public offerings (IPOs) or the legal institutions and verified some meaningful determinants of VC activity. Table 1 provides an overview of the most relevant empirical studies on VC activity.

Against this background, this paper contributes to the issue of how country-specific differences in VC activity can be explained. Mayer et al. (2005) point out that most of the cross-country variation in VC is associated with country dummies, which could proxy for a variety of factors. Black and Gilson (1998) argue that traditional determinants only partially explain cross-country variations in VC development and one should look for alternative explanations. An under-researched area in the context of cross-country comparisons of VC concerns the influence of wider environmental factors, especially the role of the social and cultural context (Wright et al.2005).

More specifically, several authors refer to the importance of cultural differences towards risk for the development of VC. Baygan and Freudenberg (2000) point out the importance of a supply of capital willing to finance risky investment, whereas Black and Gilson (1998) propose that Germans could be less entrepreneurial and less willing to risk failure than Americans, leading to less demand for VC. Megginson (2004) examines VC activity in a series of countries and concludes that VC markets will likely remain different due to different country-specific features regarding, among others, a tradition of entrepreneurial risk-taking. Bontempo et al. (1997) acknowledge that differences in risky choice behavior can be either due to differences in risk attitude or differences in risk perception. Distinct subjective impressions of the risk of VC may therefore influence VC activity in a country.

In an extensive survey of the literature, Hayton et al. (2002) document that culture has important effects on entrepreneurial behavior. In general, it has been established that entrepreneurship is facilitated by cultures that are high in individualism and low in uncertainty avoidance (Shane1993; McGrath et al.1992; Mueller and Thomas2000; Baughn and Neupert2003). Similarly, Lee and Peterson (2000) propose that only countries with specific cultural tendencies will engender a strong entrepreneurial orientation. Literature thus provides fair support for the importance of cultural values for entrepreneurship, i.e. the demand side of VC activity. Evidence regarding the supply side for VC activity in general is rather inexistent so far. In a recent study, Li and Zahra (2012) attribute different levels of VC investment to variation in institutional development, and thereby examine mediation effects of individualism and uncertainty avoidance. They argue that the institutional development is the main driver for VC activity, but find that the effect of formal institutions is weaker in more uncertainty avoiding and more collectivist societies. However, in contrast to our study, Li and Zahra (2012) do not provide any behavioral explanations for the impact of culture. Besides, they merge several institutional features into a single variable raising concerns about the rigor of their results. Without doubt, the institutional environment is highly influential on the expansion of VC worldwide (Bruton et al.2005), but as previous studies have often produced ambiguous results providing contradictory predictions about the determinants of VC activity, an in-depth analysis of institutional factors is required.

We extend the literature by providing a behavioral analysis of VC activity focusing on different perceptions of risk. To our knowledge, this is the first study that empirically examines the influences of behavioral finance on VC. We consider a large dataset of 49 countries worldwide and present a cross-country cultural based analysis of VC availability. Our variable for VC availability overcomes particular shortcomings of real investment data used in other studies (amongst others, Li and Zahra2012), as we discuss in Sect. 4. While we focus on the impact of biases as suggested by behavioral finance theory, we nevertheless control for a number of other variables that could account for varying degrees of VC investments among countries. The controls include market conditions, legal environment, entrepreneurial environment, and economic development. Such thorough analysis is essential regarding the mixed evidence of prior studies about the determinants of VC activity. Our findings with respect to the importance of uncertainty avoidance and individualism are robust to all of these control variables. We provide additional robustness checks with alternative measures for VC activity and national culture, an alternative sample composition and period as well as an alternative estimation methodology.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review the literature on behavioral finance and relate it to VC investment. In Sect. 3, we discuss the link between individualism and overoptimism as well as uncertainty avoidance and overcaution and develop hypotheses on the way culture may affect VC. In Sect. 4, we describe the data applied. In Sect. 5, we discuss the results of our empirical analysis and report several robustness checks. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background

To better explain certain market phenomena, economics and finance have been shifting from a rational agent approach towards a behavioral approach (Conlisk1996). Most financial decisions are characterized by a high degree of uncertainty and complexity, where the “homo economicus” operates as if she or he undertakes exhaustive searches over all possible choices, evaluates all consequences and then picks the best alternative (Baltussen2010). However, psychological understanding suggests that people are not able to behave in such a way, as people are limited in their abilities and capabilities to solve particularly complex problems (Simon1959). Therefore various financial phenomena can be better understood incorporating models in which agents are not fully rational, either because of preferences or because of mistaken beliefs. Behavioral finance has two peculiar building blocks: cognitive psychology and the limits of arbitrage (Ritter2003). Cognitive psychology refers to how people think and is one of the fundamentals of our analysis.

Behavioral finance argues that psychological forces intervene with the concept of the traditional rational agent approach (Shefrin1999). Because psychology systematically explores human behavior, it can provide important insights about how humans differ from the way they are traditionally characterized by economists (Rabin1998). To offer a concise forecast, behavioral models usually specify the pattern of agents’ irrationality, referring to the widespread evidence provided by cognitive psychologists (see for an overview Barberis and Thaler2003). The biases that arise when beliefs or preferences diverge from rationality are considerable (Kahnemann et al.1982). This heterogeneity in beliefs can be due to asymmetric information or to intrinsic differences in how to view the world. Intrinsic differences in perception are caused by underlying social norms and immanent emotions which might be inherited either biologically or culturally (Conlisk1996).

The goal of our empirical research is to understand whether sentiment does affect venture capital investment, and if so, through which channel. VC is a special type of equity finance provided to young, high-risk and often high-technology firms without tangible assets and is therefore also known as “risk capital” (see Gompers and Lerner2001a; Denis2004; Wright et al.2005, for reviews of the literature). New ventures involve a high level of uncertainty as well as a high risk of failure, and statistically less than one third of VC investments will finally undergo an IPO or an acquisition by another company (Fenn et al.1997). As indicated above, countries have shown different success in channeling funds to early-stage companies in high growth sectors, and disparities in VC markets across countries could arise from several factors. On the supply side, there may not be sufficient funds available or investors may be unwilling to finance risky projects. On the demand side, differences may be due to a lack of investment-ready small firms or the absence of risk-taking entrepreneurs (Thompson and Wehinger2006). We therefore can assume that the risk associated with a certain VC project plays a prominent role in the evaluation of whether the project will be realized or not.

Previous research has demonstrated that risk propensity, i.e. the willingness to knowingly take risk, is particularly not related to venture formation (Busenitz and Barney1997). Instead, risk perception is the crucial factor which drives entrepreneurial activity (Forlani and Mullins2000). Risk perception is found as the intermediate construct that influences entrepreneurial decision making (Sitkin and Weingart1995). Kahneman and Lovallo (1993) have suggested that individuals take risky actions because they perceive less risk than others. Even when evaluating identical situations, some individuals conclude the situation is very risky, whereas others believe it is not. Following this reasoning, individuals start ventures because they do not perceive the risks involved, not because they knowingly accept high levels of risk. Accordingly, perceived risk is a significant aspect of how entrepreneurs evaluate proposed projects (Keh et al.2012).

Literature provides extensive support for cross-country variations in risk perception. It has been established that individuals in some countries generally tend to overestimate risk, whereas in others tend to underestimate risk, depending on the cultural background (Boholm1998). For example, Slovic et al. (1991) demonstrate cross-cultural differences in the perception of the riskiness that poses threats to health. Kleinhesselink and Rosa (1994) report evidence of perceptions of risk related to safety concerns determined by national culture. Bontempo et al. (1997) observe cross-national differences in the perception of the riskiness of financial gambles. Weber and Hsee (1998) find cross-cultural differences in risk preference as measured by prices for risky financial options and show that these differences are almost entirely predictable by differences in the way respondents perceived the risk of these options.

Risk perception is a subjective assessment of risk resulting in overestimation or underestimation of the true risk. Some observers have suggested that decisions in the context of VC are primarily subjective assessments (Ruhnka and Young1991). Returns from VC investments are usually highly uncertain due to a lack of quantifiable financial and market data (Cochrane2005). Hence, different risk perceptions may considerably affect the generation of higher or lower estimates of the true probability of success of a potential project. If an entrepreneur or an investor overestimates the success probability of a VC project, the project is more likely to be realized. If they underestimate the success probability, the project is more likely to be neglected.

3 Individualism, uncertainty avoidance and venture capital

In the following, we discuss the relation between the cultural dimensions of individualism and uncertainty avoidance and VC. Simon et al. (1999) show that risk perceptions may differ between individuals because certain types of cognitive biases lead individuals to perceive more or less risk. Individualism and uncertainty avoidance are related to behavioral biases, in particular overoptimism and overcaution, which induce distorted risk perceptions and consequently may influence investments (and thus VC activity) in a country. Therefore, a complete explanation of VC financing and investment patterns requires examining both types of irrationality at the same time. In addition, overoptimism and overcaution can affect the entrepreneur as well as the investor.

3.1 Individualism and venture capital

Individualism describes the relationship between the individual and the collectivity that prevails in a given society. In individualist societies the ties between individuals are loose, and everyone is expected to look after him- or herself. In the polar type, collectivist societies, people are integrated into strong groups which they are unquestioningly loyal to (Hofstede2001).

The evidence in the psychology literature suggests a tight relationship between individualism and overoptimism, i.e. unrealistic optimism. Markus and Kitayama (1991) indicate that people in individualistic cultures think positively about their abilities. Van den Steen (2004) argues that when individuals are overoptimistic about their abilities, they tend to overestimate the precision of their predictions, whereas in collectivist cultures, people are concerned with behaving properly and exert high self-monitoring. Church et al. (2006) discuss that high self-monitoring helps to reduce the cognitive bias caused by overoptimism. Odean (1998) demonstrates that overoptimism leads to a miscalibration in beliefs. Van den Steen (2004) further shows that an agent who tries to choose the action that is most likely to succeed, is more likely to select an action of which he overestimated the likelihood of success.

Overoptimism is likely to affect both the demand and the supply side of VC. As Smith (1926, p. 109) already noticed, entrepreneurs must be invoked with “the contempt of risk and the presumptuous hope of success”. In this vein, Cooper et al. (1988) show that business owners tend to be overoptimistic about the outcome of their business, thereby overestimating the likelihood of success. De Meza and Southey (1996) propose that only optimists become entrepreneurs. Camerer and Lovallo (1999) verify that optimistic biases influence the entry into competitive markets. Giat et al. (2010) argue that optimism affects investment decisions.

The survey of the literature suggests that entrepreneurs and investors in individualistic cultures are likely to be overoptimistic about project outcomes and tend to overestimate the true probability of success of a VC project. Projects are more likely to be realized when the level of overoptimism is higher, and therefore we expect to find higher VC activity in those countries.

Hypothesis 1:

The VC activity in a country is positively related to its level of individualism.

3.2 Uncertainty avoidance and venture capital

Uncertainty avoidance deals with a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity and refers to its search for truth. Uncertainty avoiding cultures try to avoid unusual and unknown situations and cope with them through strict rules and security measures. The opposite type, uncertainty accepting cultures, is more tolerant and tends to have only few rules (Hofstede2001).

Psychology literature suggests a connection between uncertainty avoidance and overcaution. Following Hofstede (2001), cultures with high levels of uncertainty avoidance are motivated by a fear of failure as opposed to a desire to achieve success. Fear is a feeling that distorts the risk perception by exaggerating risk. Lerner and Keltner (2001) find that fearful people have tendencies to focus on potential “worst case” outcomes. Lerner et al. (2003) analyze the effects of fear on risk judgments and find that people who experience stronger fear express pessimistic risk estimates and increase plans for precautionary measures. This behavior of overcautious reaction is supported by Johnson and Tversky (1983) who show that negative emotions trigger more pessimistic risk estimates. Lerner et al. (2004) demonstrate that the results hold when testing the impact of fear on behavior with financial consequences.

Overcaution is likely to be associated with the supply and demand side of VC. Kihlstrom and Laffont (1979) argue that overcautious and more risk averse individuals become workers while only individuals with opposed characteristics become entrepreneurs. McGrath et al. (1992) find that business owners emphasize cultural values of risk and excitement whereas non-business owners highlight caution and fear of failure. Beugelsdijk and Frijns (2010) reason that uncertainty avoiding countries are more risk averse and perceive investments as more risky than they really are.

The review of the literature indicates that entrepreneurs and investors in uncertainty avoiding cultures are likely to be overcautious about project outcomes and tend to underestimate the true probability of success of a VC project. Projects are more likely to be neglected in countries with higher levels of overcaution, and therefore we expect to find lower VC activity in those countries.

Hypothesis 2:

The VC activity in a country is negatively related to its level of uncertainty avoidance.

4 Data description and summary statistics

We attempt to explain the cross-country variation in VC activity based on variations in individualism and uncertainty avoidance and a set of control variables. Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for our dataset can be found in Table 2.

4.1 Dependent variable: venture capital

The key variable we look at is the VC availability index as reported in the World Economics Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2008–2009. The report draws on data from the Executive Opinion Survey, where actual participants in the economies provide their expert opinions on various aspects of the business environment in which they operate. The survey was completed by 12,297 business leaders in 134 countries, which represents an average of 91 respondents per country. Despite skepticism among some researchers, the use of survey data is growing in economic analysis as it offers timely and unique measures which are not available otherwise.

The VC availability index evaluates the answers to the question: “In your country, how easy is it for entrepreneurs with innovative but risky projects to find venture capital? (1 = impossible, 7 = very easy)”. Due to the large sample size and the large number of participating countries, the data provides a distinctive source of insight and a qualitative portrait of each country’s environment and allows comparing the economic situation among countries. Alternative measures for VC activity are based upon real investment data. Data on the amount of VC investments in a country can be obtained, for example, from the VentureXpert database from Thomson Reuters. We use data on real investment volume for robustness checks of our empirical analysis. As expected, VC availability and VC investments are correlated (p = 0.61, p £ 0.01). However, our main analysis focuses on the surveyed availability of VC because data which rely on real VC investment feature several shortcomings. Kaplan et al. (2002) compare actual contracts and VC databases and find that measures provided by databases are often incomplete and noisy. Imad’Eddine and Schwienbacher (2012) discover that VC databases are biased towards the US and have less developed coverage of Europe and Asia. Dai et al. (2012) unveil that small firms are likely to be underrepresented in VC databases. Moreover, when investment data is scaled by the GDP in each country, countries with exceptionally high or low VC activity compared to the size of the economy obtain extreme values. This is for instance the case with notably small countries featuring a very large VC industry (like Singapore for example) or relatively big countries with a still underdeveloped VC industry (like Argentina for example). More importantly, we are worried that because of the relative recentness of VC, real investment data until now is of very limited use for cross-country comparison. The latter issue is crucial for numerous countries. Lerner et al. (2009) demonstrate that the volume of VC in Africa, the developing Middle East, Eastern Europe, central Asia and Latin America experienced enormous increases in 2006 and 2007 but was almost non-existing before that time. Hence, investment data in those countries probably does not yet fully reflect the principal availability of VC, as the VC markets are still at an early stage, but developing rapidly. Until in those countries the VC market has stabilized and reached an equilibrium state, investment data will be a suboptimal measure for the theoretically optimal extent of VC activity. The finding of Lerner et al. (2009) also implies that averaging investment volume over a period which includes years prior 2007 seriously biases the data. Average investment volume over such time periods incorrectly suggests low VC availability in countries where VC has only recently begun to develop. We can support this conjecture by comparing the two different measures of VC activity for subsamples of our data. The correlation between VC availability and VC investments is 0.75 for the OECD founder states, but significantly lower with 0.50 for other countries. We interpret this that only in countries which have been among the wealthy nations for a long time already, VC availability and actual VC investments are close substitutes. However, for other countries, due to the relatively recentness of VC financing, only VC availability has sufficient predictive power of the willingness of market participants to either demand or supply VC. Besides, data on real investments is highly leptokurtic, which makes it less suitable for an empirical analysis.

4.2 Independent variables: individualism and uncertainty avoidance

Data on individualism and uncertainty avoidance comes from a cross-country psychological survey conducted by Geert Hofstede. The database contains survey results collected from 116,000 IBM employees in 72 countries between 1967 and 1973. Through theoretical reasoning and statistical analysis, Hofstede revealed four main cultural dimensions on which country cultures differ and which address basic societal problems: individualism, power distance, masculinity and uncertainty avoidance. A fifth dimension labeled long-term orientation was added later. Each index is calculated from the country mean scores on several questions about the employees’ attitudes toward work and private life. We only consider individualism and uncertainty avoidance in our analysis, as the literature does not report any established links between the other cultural dimensions and behavioral biases in the context of VC activity.

Uncertainty avoidance scores are highest in Greece (most uncertainty avoiding) and lowest in Singapore (least uncertainty avoiding). Individualism is highest in the US (most individualistic) and lowest in Venezuela (least individualistic). VC availability appears to be positively associated with individualism (p = 0.36, p £ 0.10) and negatively associated with uncertainty avoidance (p = − 0.56, p £ 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Following prior studies, we refer to Hofstede’s model as the main cultural model in our study. The initial dimensions of Hofstede are derived from cross-cultural research which took place from 1967–1973 and concerns may be raised that the data is outdated. There have been several novel alternative cultural dimensions and over the last decade there has been considerable debate over the use of such models. However, Hofstede’s values are still the most widely used for the measurement of national culture and therefore most established (Kirkman et al.2006). Their employment helps to develop a commonly acceptable, well-defined and empirically based framework to characterize culture and facilitate comparison with other studies. In addition, Hofstede’s dimensions are unlikely to have lost their validity over time as, on the one hand, cultural values remain very stable over time (Sondergaard1994), and on the other hand, cultural values provide rather than an absolute position information about a country’s relative position to other countries, which changes scarcely (Tang and Koveos2008). In this vein, Tang and Koveos (2008) further show that certain cultural dimensions indeed reflect stable institutional factors such as religion, language, climate, and legal origin. Moreover, recent cross-cultural research has also validated Hofstede’s work (see, for an overview, Leung et al.2005). Most of the cultural dimensions identified by recent studies are conceptually related and empirically correlated with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, suggesting that the Hofstede framework is quite robust.

4.3 Control variables

In addition to individualism and uncertainty avoidance, we explore a large number of variables that might explain cross-country variation in VC activity. These variables are discussed in later sections and described in more detail in Table 3. Almost all control variables exhibit high correlations with VC availability. From the mixed results from the different studies, we may infer that neither financial nor legal systems, nor other determinants like labor market rigidities or tax rates are the main explanations for the pronounced differences in VC activity in different countries (Mayer et al.2005), which supports our approach.

5 Empirical findings

To explore the relationship between individualism, uncertainty avoidance and VC while controlling for other country factors, we estimate multivariate regression models. We first present a linear regression model of the continuous variable VC availability as a function of our focal variables of interest, individualism and uncertainty avoidance, and a set of other factors. In the latter part of the section we provide a linear model using an alternative dependent variable and an alternative empirical model using a logistic specification.

5.1 Regression results

Table 4 presents results of the multivariate regression of the continuous variable VC availability on individualism and uncertainty avoidance after controlling for several control variables. The model is of the form

where VC is the VC availability, IND is the individualism index, UAI is the uncertainty index, and Ci is a set of country-specific control variables representing the market conditions, legal and entrepreneurial environment as well as the economic development in a country. To avoid multicollinearity, we first cluster control variables with a similar background, but then include all variables together, in order to reduce concerns about omitted variables. Since our cultural variables are measured at the country level, we do not include country fixed effects. We standardize both the dependent and independent variables (the mean is set to zero and the standard deviation to one) so that the coefficient estimates can be directly compared within and across regressions.

The results indicate that individualism and uncertainty avoidance play a significant role in explaining the cross-country variation in VC availability. As expected, individualism has a significant positive impact on the VC availability in a country, whereas uncertainty avoidance has a significant negative impact. When including the legal environment separately in the regressions, individualism loses its significance once, which can be traced back to problems of multicollinearity. The condition number of this regression is 43.75 (≫ 15 = critical value) and the variance proportion of accounting standards is 0.88 (≫ 0.5 = critical value), suggesting that a collinearity problem associated with this variable occurs. We have estimated a considerable number of unreported regression models with varying clusters of control variables, and individualism and uncertainty avoidance load significantly with a consistent sign on VC availability, suggesting that our earlier inferences are not due to the exclusion of country-level variables that are correlated with national culture. We continue to estimate strong relations between our cultural variables and VC availability in the horserace regression, which includes all country-level control variables. In the basic specification in the first column, the cultural variables are able to explain 44% of cross-country variations in VC.

Since both dependent and independent variables have been standardized for our regressions, the estimates are easy to interpret in economic terms. The original variable VC availability before standardization has a mean of 3.48 and a standard deviation of 0.83; and in the first column individualism has a coefficient estimate of 0.32, and uncertainty avoidance has a coefficient estimate of − 0.49. This estimate implies that, all else equal, a one-standard-deviation increase in individualism would induce a 0.32 ´ 0.83 = 0.2656 increase in the VC activity measure, whereas a one-standard deviation increase in uncertainty avoidance would induce a 0.49 ´ 0.83 = 0.4067 decrease in the VC measure. In percentage terms, relative to the mean of VC availability, this corresponds to about an 8% increase and 12% decrease respectively in VC availability, which is economically significant. Uncertainty avoidance exhibits a stronger influence on VC availability than individualism, which is consistent with the correlations reported above.

We acknowledge that the data on VC availability might be biased towards the supply side of VC but believe that it is an appropriate measure for overall VC activity nevertheless. As we have demonstrated in the introductory section, several studies have shown that the level of entrepreneurship in a country is positively related to its level of individualism and negatively related to its level of uncertainty avoidance. The demand side of our hypotheses is therefore already well supported from the literature, whereby our empirical analysis documents similar effects for the supply side of VC. As both the demand and supply side of VC are likely affected by individualism and uncertainty avoidance in the same direction, VC activity should be impacted as a whole. Robustness checks with an alternative variable on real VC investments support this reasoning.

One might still object that the VC availability measure actually captures the specific relation between demand and supply of VC. If VC demand is low, but VC supply is even lower, this would result in a high value of VC availability. However, in this case, overall VC activity in absolute terms would be low due to a lack of entrepreneurial activity. Likewise, if VC supply is high, but VC demand is even higher, this would result in a low value of VC availability, but total VC activity would indeed be high. Though these combinations of VC supply and demand might eventuate, the high correlation between VC availability and real VC investment (p = 0.61, p £ 0.01) suggests that these would be rare exceptions.

The empirical findings confirm both of our hypotheses. The higher the degree of individualism, and the lower the degree of uncertainty avoidance in a country, the higher the VC activity. Though the values of R2 can be increased after including control variables, the general results hold. The various control variables will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

5.1.1 Control for market conditions

Several papers have used an institutional perspective in order to explain cross-country differences of VC markets. Early work focused on the financial environment, in particular the stock market as one of the central exit alternatives. The exit process is of principal interest to VC investors because portfolio companies typically do not generate enough cash to pay dividends or repurchase shares. Thus, adequate returns can only be derived from capital gains upon divesture. Furthermore, an exit mechanism provides a well-working financial incentive for equity-compensated managers. While there are different mechanisms to liquidate an investment, as a sale to another financial investor or an industrial company, an IPO is generally seen as the most rewarding exit for the venture capitalists as well as the entrepreneur (Black and Gilson1998; Cochrane2005; Fleming2004; Cumming et al.2006). Going public normally yields the highest returns and also strengthens the entrepreneurial control as shareholding becomes more diffused. Specifically, Black and Gilson (1998) argue that the ability to realize gains through an IPO is critical to the existence of an active VC market because it allows the venture capitalist and the entrepreneur to enter into an implicit contract over future control of the portfolio company and this contract may not be easily duplicable in a bank-centered system. Going public will simultaneously return wealth to the venture capitalist and control to the entrepreneur (assuming that shareholding following an IPO is typically dispersed), while a sale to another investor will not result in a return of control to the entrepreneur. Hence, if only a sale to another single investor can ex ante be realistically expected, the entrepreneur’s incentives will be diluted.

In this spirit, Black and Gilson (1998) test the significance of the relation of IPOs and capital contribution to venture capital funds over time in the US and find evidence that IPOs trigger fundraising in the succeeding year. Jeng and Wells (2000) examine the determinants of VC for a sample of 21 countries and also demonstrate the importance of IPOs. In their US based study, however, Gompers and Lerner (1998) do not find any significant relation between IPOs and VC activity. In a recent study conducted by Lerner et al. (2009) on private equity worldwide, the importance of equity market development, measured by stock market capitalization divided by GDP, for the development of VC is confirmed (see also Schertler2003). On the other hand, Jeng and Wells (2000) find that market capitalization growth is not a significant determinant of VC. Groh et al. (2008), in a questionnaire based survey, further demonstrate that public stock markets and the IPO markets are not as relevant as expected for the international allocation of VC.

We control in our empirical analysis for the availability of public equity funding by using the Global Competitiveness Report index on how easy equity can be raised by issuing shares on the public stock market and for the stock market capitalization scaled by GDP (taken from Djankov et al.2006). Table 4 indicates that the potential exit through an IPO is important for the VC activity which is in line with the results from Black and Gilson (1998) and Jeng and Wells (2000). The relative size of the stock market does not have explanatory power which again is consistent with Jeng and Wells (2000) but contrasts with Schertler (2003) and Lerner et al. (2009).

5.1.2 Control for legal environment

The view of the importance of stock markets for VC has been questioned, among others, by Armour and Cumming (2006), who claim that the legal environment matters as much as the strength of stock markets and that liberal bankruptcy laws foster entrepreneurial demand for venture capital. The importance of law for many aspects of finance is widely recognized. Several studies illustrate that legal institutions influence capital structure, dividend payout ratios, repurchasing of shares, and returns on capital markets (La Porta et al.1997,1998,2000; Berkowitz et al.2003; Himmelberg et al.2002; Klapper and Love2004). Legality, in this view, is a central mechanism to mitigate agency problems between outside shareholders and entrepreneurs and therefore enhances the development of (VC) markets. Because an active public market is necessary for a vibrant VC market (Black and Gilson1998), we would expect that a better legal system would go along with more VC activity.

In addition, stronger investor protection should foster VC funding because investing in support activities, which are an essential part of VC (Sahlman1990; Barry1994), is only worthwhile if the legal system ensures that these efforts will not be wasted (Bottazi et al.2008). Furthermore, to mitigate the agency conflicts arising at the financing of young growth companies with few tangible assets (Amit et al.1998), venture capitalists typically use a relatively complicated contractual design consisting of, among others, financing instruments such as convertible securities and staging (Kaplan and Strömberg2003,2004; Antonczyk et al.2008). The feasibility of using these contracts depends on the legal regime (Lerner and Schoar2005; Cumming et al.2010). Cumming et al. (2006) illustrate that, for the Asia-Pacific region, a higher quality of a country’s legal system is related with a greater likelihood of exit through IPO or trade sale. They further demonstrate that the quality of the legal system is considerably more directly connected to IPO exits than the size of a country’s stock market. Also, Lerner et al. (2009) provide evidence that the protection of minority shareholders impacts the level of VC activity in a country.

Jeng and Wells (2000) note the importance of good accounting standards. Investors will demand a higher risk premium if reliable information is scarce, resulting in more expensive funding for the company. High quality accounting standards can lower information asymmetries between the entrepreneur and the venture capitalist and therefore make funding more feasible and lower the cost of capital. Information asymmetries are particularly pronounced for early stage investments in high-tech companies (Sahlman1990; Kaplan and Strömberg2003). However, since VC funds scrutinize the possible investments and hold major portions of the equity, reporting quality might be of less importance for VC funds than for outside investors (Wright and Robbie1998). This could result in less VC activity in countries with good accounting standards as other external capital sources besides VC, which rely more on financial statements, might be easier available. Consistent with this thought, Jeng and Wells (2000) even find a negative relationship between the quality of accounting standards and VC activity. On the other hand, Cumming et al. (2010) show that a higher legality index, including accounting standards, has a positive impact on the governance structure of investments in the VC industry.

One would also expect that lower tax rates support the level of VC activity by enhancing investment incentives. Gompers and Lerner (1998) demonstrate that the capital gains tax rate influences the level of VC activity. But neither Jeng and Wells (2000), Romain and van Pottelsberghe (2004), nor Lerner et al. (2009) find any significant influence of the tax rate on VC activity in a particular country.

Thus, we anticipate that better legality should have a positive impact on the level of VC activity. We control for the impact of legal institutions by considering the quality of minority stockholders’ protection and accounting standards. Both determinants are represented by indices taken from the Global Competitiveness Report. We further control for the total tax rate in the respective country. Table 4 indicates that the strength of accounting standards has a positive influence on VC availability. This result is in line with the arguing—but not the empirical findings—in Jeng and Wells (2000) and the findings in Armour and Cumming (2006) and Cumming et al. (2010). However, our result in relation to the impact of accounting standards is only weak insofar that the significance merely holds before simultaneously controlling for other variables.

Unlike Lerner et al. (2009) we are unable to find any relationship between investor protection and VC activity which might indicate that venture capitalists are able to implement favorable contracts regardless of the legal regime (Kaplan et al.2007). The tax rate has apparently no influence on VC activity, which is consistent with most other empirical studies on VC.

5.1.3 Control for entrepreneurial environment

Jeng and Wells (2000) demonstrate the importance of labor market rigidities for early stage investments. They argue that labor market rigidities have a negative impact on the development of VC markets. Strict labor laws make hiring employees difficult for companies because they deprive the company of the flexibility to dismiss people later should this become necessary. In addition, in some countries, leaving a company is accompanied by large costs stemming from losing pension benefits (Sahlman1990). The importance of labor market rigidities is also demonstrated by Romain and van Pottelsberghe (2004). However, Lerner et al. (2009) do not find any significant impact of labor market rigidities on VC activity while Schertler (2003) surprisingly shows a significantly positive relationship.

Baygan and Freudenberg (2000), in the context of OECD countries, highlight the importance of the barriers to entrepreneurship as a principal determinant on VC market differences across countries. However, Lerner et al. (2009), in their worldwide study, report no significant influence of barriers to entrepreneurship on VC.

We use several measures for the entrepreneurial environment. We control for labor market rigidities by using the index on hiring and firing practices provided by the Global Competitiveness Report. To reflect the barriers to entrepreneurship, we use the burden of government regulation index which is also taken from the Global Competitiveness Report. In both settings the control for labor market rigidities does not have explanatory power which is in line with Lerner et al. (2009) and with the mixed results from other studies. Our results further weakly indicate that less burdensome government regulation fosters VC availability which is consistent with Baygan and Freudenberg (2000).

5.1.4 Control for economic development

As Gompers and Lerner (1998) point out, there are likely to be more attractive opportunities for entrepreneurs if the economy is large and growing. The development of the economy should therefore be correlated with entrepreneurial activity which is generally assumed to be an important determinant of VC development (Armour and Cumming2006; Romain and Van Pottelsberghe2004; Da Rin et al.2006). Thus, we may expect a positive relationship of the development of VC markets to macroeconomic variables such as the level of GDP per capita, since a strong economy should exhibit a high level of start-up activity and an increase in the demand for VC funds (Lerner et al.2009).

We therefore control in our empirical analysis for the level of development by using GDP per capita. We find only weak evidence that the level of VC availability is determined by the level of wealth, as the significance is lost when controlling simultaneously for other variables as well. Latter outcome is consistent with the results from Jeng and Wells (2000) as well as Armour and Cumming (2006).

5.2 Results using an alternative measure for the dependent variable

To ensure accurate inference for the main results presented above, we provide additional checks in this section using an alternative measure for the dependent variable. Despite the drawbacks mentioned before, we use data on real VC investments in a country. Data is from the Thomson Reuters VentureXpert database. We use the total sum of VC invested in each country for each year in million US-dollars and compute the average over the years 2003 until 2007 in order to obtain a representative sample of volume. We select this period so that our data is not affected by the private equity crash from 2000 to the beginning of 2003 and the credit crunch in the late-2000s.

As discussed earlier, averaging investment data which include years before 2007 are probably subject to serious distortions due to the recentness of VC in many countries. But because VC investment data are highly volatile year-on-year we are left with no other choice. While some authors use averaging as we do (Jeng and Wells2000; Armour and Cumming2006; Lerner et al.2009), other apply a panel regression (Schertler2003, or Li and Zahra2012). We do not use a panel regression because we are concerned that the observations are not independent. As the features of the countries only change slowly, using annual data likely results in inflated significance levels (Lerner et al.2009).

We divide the data for each country by GDP for comparative purposes across countries. VC investment/GDP is highest in Singapore (18.42) and lowest in Argentina (0.00), the mean is 2.61, the median is 1.12, and the standard deviation is 3.63. Given the highly leptokurtic distribution of the data points, we exclude countries with values that depart more than three standard deviations from the mean (Singapore, Israel, the US). Including these countries does not change the sign of the coefficients but weakens the significance contingently and reduces the overall fit of the model measured through R2 considerably by about one third. Winsorising the data instead yields results similar to those for the trimmed data set. We again standardize the data and estimate the same regression models as before. The findings are reported in Table 5.

The main results of our study remain unaffected. Individualism has a significantly positive impact on VC investments, whereas uncertainty avoidance exhibits a significantly negative effect. These relationships are stable throughout all regression models and provide additional support for our hypotheses.

Including control variables into the basic regression model reported in the first column does not improve the model significantly, as the values of R2 remain almost unchanged. Interestingly, in all of the regressions, none of the control variables displays any significant effects on VC investments in a country. This finding supports the reservations against this variable we expressed before. Data on real VC investments exhibit severe biases which render it less suitable for an empirical analysis of VC activity.

5.3 Results using an alternative sample period

We alternate the sample period in order to insure that our results are not driven by selecting a particular year during national or international business cycles that is in some sense special. We check whether our results are robust across time and reproduce our regression analysis with data from 2003. The results in Table 6 (column one and two) using this alternative sample period are again fundamentally unchanged in both sign and significance to the previous findings. National culture has important effects on VC activity across countries. For brevity, we only report the results for the basic specification and the horserace regression including all country-level controls. We solely present the coefficient on the two cultural variables of interest as the other coefficients are very much alike to those presented beforehand.

5.4 Results using an alternative sample composition: sub-sample regression

Concerns about the validity of the dataset could occur from the fact that the cultural variables have been collected from 1967–1973, whereas the data for the explained VC variable as well as other explanatory variables are from 2008. This might be problematic, in particular since the political and economic environment in some countries of our dataset has changed substantially in the last 40 years. A prominent large group of countries which experienced disruptive shifts are the Eastern European countries. In Eastern Europe, the political system has changed completely in the 1990s, triggering high economic growth. These processes might also have altered the perception of people in these countries.

To isolate such effects, we perform out-of-sample tests that do not include Eastern Europe. We therefore remove the nine Eastern European countries and repeat our main analysis using the subsample. In Table 6 (column three and four) we show that the previous results are not driven by sample composition biases. The results for the cultural variables remain unchanged. We find again that individualism has a significant and positive impact on VC activity whereas the effect of uncertainty avoidance is significantly negative.

5.5 Results using an alternative measure for national culture

To capture a possible change of culture over time we also consider alternative measures of individualism and uncertainty avoidance. Tang and Koveos (2008) develop an integrated empirical model to update the Hofstede cultural dimensions based on the changing economic environment within countries. They presume that cultural values should reflect both the institutional characteristics and the economic conditions of a country. As institutional features change very little over time, Tang and Koveos (2008) use religion, language, ethnic heterogeneity, climate, legal system, and female labor participation rate as institutional variables to explain the Hofstede cultural scores, and then derive updated scores based on GDP per capita from the 1990s. This update of cultural values has also been used by other authors (Beugelsdijk and Frijns2010).

We replicate our empirical tests using these recently developed updates of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Consistent with our previous results, the outcome in Table 6 (column five and six) shows that the updated cultural variables do not change our findings. The estimated coefficient of the updated individualism index is significantly positive, the estimated coefficient of the updated uncertainty avoidance index is significantly negative.

The usage of GDP adjusted cultural variables also addresses endogeneity concerns. Due to long time lags regarding the original Hofstede cultural dimensions, some of the explanatory variables become potentially endogenous, depending on the cultural variables (as a function of risk perception in the past) as well. Using the growth adjusted Hofstede scores support the robustness of our results and help dispel concerns that our findings could be distorted by endogeneity.

5.6 Results using an alternative model: logistic regression

We next examine the relation between the cultural dimensions of individualism and uncertainty avoidance and VC activity using a logit model. We estimate the likelihood that a country has a well developed VC market, assuming this probability is a function of our main explanatory variables of interest, individualism and uncertainty avoidance. Let VC be an indicator variable that takes 1 if a country has above average VC availability and 0 otherwise. Let P be the probability that a country has above average VC availability. The natural log of this likelihood, given the explanatory variables, is specified by

where β and γ are vectors of parameters to be estimated and F(β ´ IND, γ ´ UAI) is the cumulative logistic distribution evaluated at (β ´ IND, γ ´ UAI). In modeling the likelihood of VC availability, we use a logistic function as the underlying probability distribution. Due to the small sample size we refrain from including controls in this logistic regression.

Table 7 confirms our findings that individualism and uncertainty avoidance explain certain extents of cross-country variation in VC activity. National cultures characterized by high individualism and low uncertainty avoidance are more likely to have high VC activity. The individualism index enters the regressions with a positive coefficient and is statistically significant at the 5% level. The uncertainty avoidance index enters the regressions with a negative coefficient and is statistically significant at the 1% level. The logistic model with individualism and uncertainty avoidance as sole explanatory variables can already classify 76% of the countries correctly into above or below average VC activity countries. This simple approach again underlines the importance of individualism and uncertainty avoidance for VC.

6 Summary and conclusions

Cross-country differences in VC activity provide a challenge for traditional and behavioral finance theory. Traditional theory has already shown that market conditions, legal environment, entrepreneurial environment, and economic development impact VC investment. Behavioral theory must explain why individuals in some, but not all countries, are subject to psychological biases that influence VC investment. Our behavioral analysis helps to explain a significant portion of the variation in VC activity across countries.

The results of our study indicate that culture has an important effect on VC activity. This finding is consistent with the idea that individuals in different cultures are subject to different behavioral biases which lead to different risk perceptions. We find evidence that individuals in more individualistic countries are likely to be overoptimistic and tend to overestimate the success probability of a VC project, resulting in higher VC activity. Individuals in more uncertainty avoiding cultures are likely to be overcautious and tend to underestimate the success probability of VC projects, inducing lower VC activity.

The evidence in this paper supports the proposition that some cultures are more favorable for VC than others. This issue should be particularly interesting to countries stimulating VC activity as a means of promoting entrepreneurship. From a policy perspective, our study shows that it is necessary for policymakers to account for cultural values when designing formal policies to promote VC activities. Programs to foster VC in cultures that are low in individualism and high in uncertainty avoidance, but which assume economic behavior guided by the opposite underlying values, may run serious risk of failure.

References

Amit R, Brander J, Zott C (1998) Why do venture capital firms exist? Theory and canadian evidence. J Bus Ventur 13:441–466

Antonczyk RC, Breuer W, Brettel M (2008) Venture capital financing in Germany: the role of contractual arrangements in mitigating incentive conflicts. In: Fuchs EJ, Braun F (eds) Emerging topics in banking and finance. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge, pp 65–102

Armour J, Cumming D (2006) The legislative road to silicon valley. Oxford Econ Pap 58(4):596–635

Baltussen G (2010) Behavioral finance: an introduction. SSRN Working Paper.

Barberis N, Thaler R (2003) A survey of behavioral finance. In: Constantinides GM, Harris M, Stulz RM (eds) Handbook of the economics of finance. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1053–1128

Barry CB (1994) New directions in research on venture capital finance. Finan Manage 23(3):2–15

Barry CB, Muscarella CJ, Peavy JW III, Vetsuypens MR (1990) The role of capital in the creation of public companies. J Finan Econ 27:447–471

Bascha A, Walz U (2001) Financing practices in the German venture capital industry: an empirical study. In: Gregoriou GN, Kooli M, Krauessl R (eds) Venture capital in Europe. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 217–247

Baughn CC, Neupert KE (2003) Culture and national conditions faciliating entrepreneurial start-ups. J Int Entrep 1:313–330

Baygan G, Freudenberg M (2000) The internationalisation of venture capital activity in OECD countries: implications for measurement and policy. STI Working Papers 2000/7, OECD: Paris

Berkowitz D, Pistor K, Richard J-F (2003) Economic development, legality and the transplant effect. Europ Econ Rev 47(1):165–195

Beugelsdijk S, Frijns B (2010) A cultural explanation of the foreign bias in international asset allocation. J Bank Finance 34:2121–2131

Black BS, Gilson RJ (1998) Venture capital and the structure of capital markets: banks versus stock markets. J Finan Econ 47:243–277

Boholm A (1998) Comparative studies of risk perception: a review of twenty years of research. J Risk Res 1(2):135–163

Bontempo RN, Bottom WP, Weber EU (1997) Cross-cultural differences in risk perception: a model-based approach. Risk Anal 17(4):479–488

Bottazi L, Da Rin M, Hellmann T (2008) What is the role of legal systems in financial intermediation? Theory and evidence. J Finan Intermediation 18:559–598

Bruton G, Fried VH, Manigart S (2005) Institutional influences on the worldwide expansion of venture capital. Entrep Theory Pract 29(6):737–760

Busenitz L, Barney J (1997) Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. J Bus Ventur 12:9–30

Camerer C, Lovallo D (1999) Overconfidence and excess entry: an experimental approach. Am Econ Rev 89(1):306–318

Church A, Katigbak MS, Del Prado AM, Ortiz FA, Mastor KA, Harumi Y, Tanaka-Matsumi J, De Jesus Vargas-Flores J, Ibanez-Reyes J, White FA, Miramontes LG, Reyes JAS, Cabrera HF (2006) Implicit theories and self-perceptions of traitedness across cultures: toward integration of cultural and trait psychology perspectives. J Cross Cult Psychol 37:694–716

Cochrane JH (2005) The risk and return of venture capital. J Finan Econ 75:3–52

Conlisk J (1996) Why bounded rationality? J Econ Lit 34:669–700

Cooper AC, Woo CY, Dunkelberg WC (1988) Entrepreneurs’ perceived chances for success. J Bus Ventur 3:97–108

Cumming D, Fleming G, Schwienbacher A (2006) Legality and venture capital exits. J Corp Financ 12:214–245

Cumming D, Schmidt D, Walz U (2010) Legality and venture governance around the world. J Bus Ventur 25:54–72

Da Rin M, Nicodano G, Sembenelli A (2006) Public policy and the creation of active venture capital markets. J Public Econ 90(8–9):1699–1723

Dai N, Jo H, Kassicieh S (2012) Cross-border venture capital investments in Asia: selection and exit performance. J Bus Ventur forthcoming

Denis DJ (2004) Entrepreneurial finance: an overview of the issues and evidence. J Corp Financ 10:301–326

De Meza D, Southey C (1996) The Borrower’s Curse: optimism, finance and entrepreneurship. Econ J 106:375–386

Djankov S, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2006) The law and economics of self-dealing. J Finan Econ 88:430–465

Fenn G, Liang N, Prowse SD (1997) The private equity market: an overview. Finan Mark Inst Instrum 6(4):1–105

Fleming G (2004) Venture capital returns in Australia. Ventur Cap 6(1):23–45

Forlani D, Mullins JW (2000) Perceived risks and choices in entrepreneurs’ new venture decisions. J Bus Ventur 15:305–322

Gebhardt G, Schmidt KM (2002) Der Markt für Wagniskapital: Anreizprobleme, Governance Strukturen und staatliche Interventionen. Perspekt Wirtschaftspolitik 3:235–256

Giat Y, Hackman ST, Subramanian A (2010) Investment under uncertainty, heterogeneous beliefs, and agency conflicts. The Rev Financ Stud 23(4):1360–1404

Gompers P, Lerner J (1998) What drives venture capital fundraising? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics 7:149–204

Gompers P, Lerner J (2001a) The money of invention. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge

Gompers P, Lerner J (2001b) The venture capital revolution. J Econ Perspect 15(2):145–168

Groh AP, Liechtenstein H, Canela MA (2008) International allocation determinants of institutional investments in venture capital and private equity limited partnerships. Working Paper No. 726, IESE Business School-University of Navarra

Hayton JC, George G, Zahra SA (2002) National culture and entrepreneurship: a review of behavioral research. Entrep Theory Pract 26:33–52

Himmelberg CP, Hubbard RG, Love I (2002) Investor protection, ownership, and the cost of capital. Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Columbia University and the World Bank

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences; comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Imad’Eddine G, Schwienbacher A (2012) International capital flows into the european private equity market. Europ Finan Manage, forthcoming

Jeng LA, Wells PC (2000) The determinants of venture capital funding: evidence across countries. J Corp Financ 6:241–289

Johnson E, Tversky A (1983) Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. J Personal Soc Psychol 45(1):20–31

Kahneman D, Lovallo D (1993) Timid choices and bold forecasts: a cognitive perspective on risk taking. Manage Sci 39:17–31

Kahnemann D, Slovic P, Tversky A (1982) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kaplan SN, Strömberg P (2003) Financial contracting theory meets the real world: an empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Rev Econ Stud 70(2):281–315

Kaplan SN, Strömberg P (2004) Characteristics, contracts, and actions: evidence from venture capitalist analyses. J Finance 59(5):2177–2210

Kaplan SN, Strömberg P, Sensoy BA (2002) How well do venture capital databases reflect actual investments. SSRN Working Paper.

Kaplan SN, Martel F, Strömberg P (2007) How do legal differences and experience affect financial contracts? J Finan Intermediation 16(3):273–311

Keh HT, Foo MD, Lim BC (2012) Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: the cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrepr Theory Pract 27(2):125–148

Kihlstrom R, Laffont JJ (1979) A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. J Polit Economy 87:719–748

Kirkman BL, Lowe KB, Gibson CB (2006) A quarter century of culture’s consequences: a review of empirical research incorporating hofstede’s cultural values framework. J Int Bus Stud 37:285–320

Klapper LF, Love I (2004) Corporate governance, investor protection, and performance in emerging markets. J Corp Financ 10:703–728

Kleinhesselink RR, Rosa EA (1994) Cognitive representation of risk perceptions: a comparison of Japan and the United States. J Cross Cult Psychol 22:11–28

Kortum S, Lerner J (2000) Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation. RAND J Econ 31:674–692

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1997) Legal determinants of external finance. J Finance 52(3):1131–1150

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (1998) Law and finance. J Polit Economy 106:1113–1155

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (2000) Agency problems and dividend policies around the world. J Finance 55(1):1–34

Lee SM, Peterson SJ (2000) Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness. J World Bus 35(4):401–416

Lerner J (1994) Venture capitalists and the decision to go public. J Finan Econ 35:293–316

Lerner JS, Keltner D (2001) Fear, anger, and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol 81(1):146–159

Lerner J, Gompers P (2002) Short-term America revisited? Boom and bust in the venture capital industry and the impact on innovation. In: Jaffe A, Lerner J, Stern S (eds) Innovation policy and the economy. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 1–27

Lerner J, Schoar A (2005) Does legal enforcement affect financial transactions? The contractual channel private equity. Quart J Econ 120:223–246

Lerner JS, Gonzales RM, Small DA, Fischhoff B (2003) Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: a national field experiment. Psychol Sci 14(2):144–150

Lerner JS, Small DA, Loewenstein G (2004) Heart strings and purse strings: carryover effects of emotions on economic decisions. Psychol Sci 15(5):337–341

Lerner J, Sorensen M, Strömberg P (2009) What drives private equity activity and success globally? The Global Economic Impact of Private Equity Report 2009. World Economic Forum, Geneva, pp 65–98

Leung K, Bhagat RS, Buchan NR, Erez M, Gibson CB (2005) Culture and international business: recent advances and their implications for future research. J Int Bus Stud 36:357–378

Li Y, Zahra S (2012) Formal institutions, culture, and venture capital activity: a cross-country analysis. SSRN Working Paper

Markus H, Kitayama S (1991) Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev 98:224–253

Mayer C, Schoors K, Yafeh Y (2005) Sources of funds and investment activities of venture capital funds: evidence from Germany, Israel, Japan and the United Kingdom. J Corp Financ 11:586–608

McGrath RG, MacMillan IC, Yang EA-Y, Tsai W (1992) Does culture endure, or is it malleable? Issues for entrepreneurial economic development. J Bus Ventur 7:441–458

Megginson W (2004) Toward a global model of venture capital? J Appl Corp Financ 16(1):7–26

Mueller SL, Thomas AS (2000) Culture and entrepreneurial potential: a nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. J Bus Ventur 16:51–75

Odean T (1998) Volume, volatility, price, and profit: when all traders are above average. J Financ 53(6):1887–1934

Rabin M (1998) Psychology and economics. J Econ Lit 36:11–46

Ritter JR (2003) Behavioral finance. Pacific-Basin Finance J 11:429–437

Romain A, van Pottelsberghe B (2004) The determinants of venture capital: a panel data analysis of 16 OECD countries. Working Paper WP-CEB 04/015

Ruhnka JC, Young JE (1991) Some hypotheses about risk in venture capital investing. J Bus Ventur 6:115–133

Sahlman WA (1990) The structure and governance of venture-capital organizations. J Finan Econ 27:473–521

Schertler A (2003) Driving forces of venture capital investments in europe: a dynamic panel data analysis. Working Paper No. 03–27

Schwienbacher A (2002) An empirical analysis of venture capital exits in Europe and the United States. Working Paper

Shane S (1993) Cultural influences on national rates of innovation. J Bus Ventur 8:59–73

Shefrin H (1999) Behavioral corporate finance. J Appl Corp Financ 14(3):113–124.

Simon HA (1959) Theories of decision-making in economics and behavioral science. Amer Econ Rev 49(3):253–283

Simon M, Houghton SM, Aquino K (1999) Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: how individuals decide to start companies. J Bus Ventur 15:113–134

Sitkin SB, Weingart LR (1995) Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: a test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Acad Manage J 38(6):1573–1592

Slovic P, Kraus NN, Lappe H, Majors M (1991) Risk Perception of prescription drugs: report on a survey in Canada. Can J Public Health 82:15–20

Smith A (1926) The wealth of nations. Modern Library, New York

Sondergaard M (1994) Hofstede’s consequences: a study of reviews, citations, and replications. Organ Stud 15(3):447–456

Tang L, Koveos PE (2008) A framework to update Hofstede’s cultural value indices: economic dynamics and institutional stability. J Int Bus Stud 39(6):1045–1063

Thompson J, Wehinger G (2006) Risk capital in OECD countries: past experience, current situation and policies for promoting entrepreneurial finance. Financ Mark Trends 90:111–151

Van den Steen E (2004) Rational overoptimism (and other biases). Amer Econ Rev 94(4):1141–1151

Weber EU, Hsee C (1998) Cross-cultural differences in risk perception, but cross-cultural similarities in attitudes towards perceived risk. Manage Sci 44(9):1205–1217

Wright M, Robbie K (1998) Venture capital and private equity: a review and synthesis. J Bus Financ Account 25(5 & 6):521–570

Wright M, Pruthi S, Lockett A (2005) International venture capital research: from cross-country comparisons to crossing borders. Int J Manage Rev 7(3):135–165

Zingales L (2000) In search of new foundations. J Financ 55(4):1623–1653

Danksagung

We are grateful to Wolfgang Breuer and an anonymous referee for their useful comments and suggestions. We thank Jan Ossenbrink for excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antonczyk, R., Salzmann, A. Venture capital and risk perception. Z Betriebswirtsch 82, 389–416 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0556-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0556-1