Abstract

Homelessness and housing instability is a significant public health problem among young sexual minority men. While there is a growing body of literature on correlates of homelessness among sexual minority men, there is a lack of literature parsing the different facets of housing instability. The present study examines factors associated with both living and sleeping in unstable housing among n = 600 sexual minority men (ages 18–19). Multivariate models were constructed to examine the extent to which sociodemographic, interpersonal, and behavioral factors as well as adverse childhood experiences explain housing instability. Overall, 13 % of participants reported sleeping in unstable housing and 18 % had lived in unstable housing at some point in the 6 months preceding the assessment. The odds of currently sleeping in unstable housing were greater among those who experienced more frequent lack of basic needs (food, proper hygiene, clothing) during their childhoods. More frequent experiences of childhood physical abuse and a history of arrest were associated with currently living in unstable housing. Current enrollment in school was a protective factor with both living and sleeping in unstable housing. These findings indicate that being unstably housed can be rooted in early life experiences and suggest a point of intervention that may prevent unstable housing among sexual minority men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An emerging body of literature has demonstrated homelessness among sexual minority (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning) youth (SMY) to be a significant public health problem.1 – 4 A 2010 report places the total number of SMY experiencing homelessness and/or housing instability in the USA between 320,000 and 400,000.5 While this estimate represents only 20 % of all homeless youth in the USA, the prevalence of homelessness among SMY may in fact be underestimated, and therefore the number of SMY affected by homeless is likely much higher. Truly accurate estimates of unstably housed SMY are difficult to obtain due in part to housing status questionnaires that often do not include items on sexual orientation,6 and in general, SMY are less likely to report their sexual orientation on surveys.4 , 7

Of the limited number of studies that have examined homelessness and housing instability among SMY, findings have suggested that SMY are distinct from homeless youth in general in several key ways. For instance, SMY are more likely to have run away and/or live on the street independently as opposed to living as part of a homeless family/unit.6 With regard to sexual minority men, a Los Angeles-based cohort study found 17 % of participants had been forced to move from a family or friend’s home because of their sexuality.8 These data suggest that housing instability may manifest itself in many forms and consequently may produce a range of physical and mental health outcomes. Homeless SMY have particularly high rates of HIV risk behaviors, suicidality, depression, physical victimization, and substance abuse problems.9 – 12 Moreover, this population as whole experiences more sexual and/or physical abuse combined with parental neglect and rejection.13 , 14 Understanding how distinct levels of housing instability among SMY correlate with the aforementioned risk factors will help to advance mechanisms to overcome them.

Many studies investigating SMY and housing stability have assessed homelessness exclusively in terms of where individuals were residing, as opposed to examining overall housing stability with regard to both living and sleeping situations. For example, Rosario and colleagues evaluated homelessness by whether or not participants had run away or been removed from the home by their parents/guardians,2 Cochran et al. examined drivers of homelessness among those who had left stable residences,9 and Gattis et al. obtained data from Toronto youth who utilized drop-in services at homeless youth agencies.12 These studies have all obtained their data from cohorts who were, at the time, unstably housed. Other more nuanced forms of housing instability exist, such as intermittently sleeping in non-residential settings. Therefore, examining housing stability and its correlates in a broader context is warranted.

Many conditions that either arise from housing instability or contribute to its emergence are known be associated with negative health outcomes. It has been documented that homeless SMY resort to survival crimes including theft, trespassing, and sex work as a means of securing shelter or resources and, as a result, they are at higher risk for interacting with the juvenile and criminal justice system.1 , 15 , 16 Engaging in sex at an earlier age is also associated with unstable housing conditions, and homeless youth have been shown to have earlier ages of same-sex sexual debut than those who are stably housed.2 Experiencing any type of adverse childhood experience (e.g., emotional or physical abuse or substance abuse/criminal behavior) is also associated with a younger age of sexual debut.17 Determining how these facets of housing instability interact with one another is essential to understanding their impact on the well-being of SMY.

In light of the extant literature, a main objective of this study was to provide a more nuanced perspective on housing stability, particularly among a sample of young sexual minority men. Specifically, by moving beyond an examination of housing instability as only defined by homelessness and instead considering unstable sleeping situations as well, we hope to provide an additional context from which to examine housing instability. This contribution to our understanding is particularly important in the lives of sexual minorities because unstable sleeping and living circumstances may provide insights into the lack of acceptance that they face from their family/peers and may also be a precursor to actual homelessness. In addition, we examined these distinct housing situations in relation to sociodemographic, interpersonal, and behavioral factors.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

Data from this analysis were derived from the baseline visit of the Project 18 Study (P18), an ongoing cohort study of young sexual minority men in the New York City metropolitan area. Study details were previously described in detail and are briefly summarized here.18 , 19 Participants were recruited through a combination of community outreach methods including flyers and Internet advertisements as well as venue-based (e.g., community centers, college campuses, bars/clubs, etc.) methods between June 2009 and May 2011. Participants were eligible if they were 18–19 years old, lived in the NYC metropolitan region, born biologically male, self-reported sex with another man in the last 6 months, and self-reported an HIV-negative or unknown serostatus. A total of n = 600 participants were enrolled into the study, and this present study employs data from the n = 598 participants with complete baseline data which was collected through an audio-computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). All study activities were reviewed and approved by New York University’s Institutional Review Board.

Main Dependent Variable

Housing status was first assessed based on an item that asked, “in the past 6 months, have you ever slept in any of these places?” Answer choices included sleeping in/on the street, park, abandoned building/automobile, public place (subway/bus station), shelter, limited stay/single room occupancy, and/or a welfare motel/hotel. Additionally, participants were asked, “in the past 6 months, have you lived in any of these places?” For this question, answer choices included living in temporary/transnational housing, jail, drug treatment facility, halfway house, and/or temporarily living with friends/family.20 For this analysis, the sleeping variables and the living variables were collapsed into two separate non-mutually exclusive binary variables: “housing slept” (yes vs. no) and “housing lived” (yes vs. no).

Covariates

Sociodemographic Characteristics

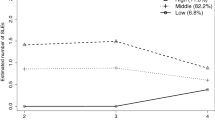

P18 participants self-reported information on their racial/ethnic background, perceived familial socioeconomic status, current educational status, sexual orientation, current relationship status, lifetime arrest history, and self-reported health. Race was categorized as Hispanic/Latino, White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Asian non-Hispanic, and Mixed Race/Other, non-Hispanic. Perceived familial socioeconomic status was categorized as “lower,” “middle,” and “upper” class. Using the work of Kinsey and colleagues, sexual identity was measured on a 7-point scale ranging from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Selecting a score from 1 to 5 allows for varying level identification with either end of the scale (0, exclusively heterosexual; 1, predominantly heterosexual, only incidentally homosexual; 2, predominantly heterosexual but more than incidentally homosexual; 3, equally heterosexual and homosexual; 4, predominantly homosexual but more than incidentally heterosexual; 5, predominantly homosexual, only incidentally heterosexual; 6, exclusively homosexual).21 In this dataset, the distribution is as follows: exclusively homosexual, 0 %; predominantly heterosexual, only incidentally homosexual, 2 % (n = 11); predominantly heterosexual but more than incidentally homosexual, 3 % (n = 15); equally heterosexual and homosexual, 12 % (n − 70); predominantly homosexual but more than incidentally heterosexual, 13 % (n = 78); predominantly homosexual, only incidentally heterosexual, 29 % (n = 176); and exclusively homosexual, 41 % (n = 248). In the present analysis, we coded the response options for the Kinsey Scale for Sexual Orientation dichotomously as exclusively homosexual versus not exclusively homosexual to be consistent with our previous research and because, as previously demonstrated, risk behavior varies by sexual behavior.18 , 22 – 24 Relationship status was assessed by whether a participant had a relationship with a male in the last 3 months and self-rated health was categorized as “excellent,” “very good,” and “good/fair/poor.” Educational status was examined dichotomously as “not currently in school/currently in school,” and lifetime arrest history was analyzed dichotomously as “yes/no.”

Interpersonal Factors

Outness

To determine sexual orientation outness, participants were asked, “Who knows that you have had sex with a man?” and for the purpose of this analysis, we examined whether participants were out to their parents, friends, teachers, and other family members including grandparents, siblings, aunts/uncles, and other relatives.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse childhood experiences were assessed by examining self-report data on the number of times a parent or other adult caregiver left the participant alone by the time they were in sixth grade, did not provide adequate clothing, hygiene, or food (lack of basic needs), and physically and/or sexually abused the participants throughout their childhood.25

Behavioral Factors

Age of sexual debut was obtained by asking participants a series of questions about their sexual history. Questions included, “At what age did you: first masturbate with someone else, perform oral sex, receive oral sex, have insertive anal sex, have receptive anal sex and have vaginal sex?” This analysis looked at each of these items both individually and collectively; extreme outliers under the age of 10 were removed.

Analytic Plan

Bivariable analyses in the form of a chi-square test of independence were used to examine the relationship of housing status with demographic characteristics, sexual orientation outness, and adverse childhood experiences variables. Correlates of housing status and age of sexual debut were also used to examine the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, outness with regard to sexual orientation status, adverse childhood experiences, and housing status in the past 6 months. Covariates significantly associated with housing status in the bivariable analyses were entered into multivariable logistic models to explain housing instability. All final multivariable logistic regression models controlled for perceived familial SES and race/ethnicity given the relationship these factors have with homelessness and housing instability. Using Pearson χ 2 goodness-of-fit tests and −2 log likelihood statistics, model fit was assessed and the final models presented are the most parsimonious models. All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 23.

Results

In this sample of young sexual minority men, 12.7 % (n = 76) self-reported unstable sleeping conditions and 18.2 % (n = 109) self-reported unstable living conditions in the prior 6 months to assessment. In bivariable analysis (Tables 1 and 2), sleeping in unstable housing was associated with educational status; those who were not currently in school were more likely to report unstable sleeping and/or living conditions (34.2 and 32.1 %, respectively) compared to those who had not slept and/or lived in unstable housing (11.5 and 10.4 %, respectively) (p < 0.05). There was a strong association between history of arrest and unstable housing where 28.9 % of those arrested had slept in and 29.4 % had lived in unstable housing compared to those who had not slept and/or lived in unstable housing (13.8 and 12.7 %, respectively) (p < 0.001). Participants who self-reported lower (48.6 vs. 30.1 %) perceived familial SES were more likely to report living in unstable housing compared to those who self-reported middle (28.4 vs. 39.1 %) or upper levels of perceived familial SES (22.9 vs. 30.9 %) (p < 0.001). Black and Mixed/Native American/Other Non-Hispanic participants were more likely to report living in unstable housing (22.0 and 19.3 %, respectively) than White, Hispanic, and Asian participants (19.3, 36.7, and 2.8 %, respectively) (p = 0.007). Self-rated health was also associated with housing stability; 33.9 % of sexual minority men who reported good/fair/poor health were unstably housed (vs. 20.4 %) compared to the 37.6 and 28.4 % who reported very good or excellent health, respectively (p = 0.009).

Regarding sexual orientation, participants who reported being out to their friends were more likely to have slept in unstable housing (p = 0.034), whereas participants who reported being out to their parents, other family members, and teachers were more likely to have lived in unstable housing (p = 0.003, p = 0.002, and p < 0.001, respectively). Numerous findings also emerged with regard to adverse childhood experiences. Facing neglect and abuse as a child was associated with unstable housing as a young adult; 59.2 % of participants who slept in and 61.4 % who lived in unstable housing had been left alone at least one time by the time they were in sixth grade (p = 0.017 and p = 0.018, respectively). Experiencing lack of basic needs as a child was significantly associated (p < 0.001) with both sleeping and living in unstable housing. Experiencing physical abuse in the form of kicking, hitting, or punching from a parent and/or adult caregiver at least once (71.1 % who slept in and 77.1 % who lived in) was significantly associated (p = 0.013 and p = <0.001, respectively) with unstable housing and participants who experienced sexual abuse from a parent and/or adult caregiver were more likely to live in unstable housing (p = 0.007).

In terms of behavioral factors, a younger age of sexual debut was significantly associated with unstable housing. The mean age of sexual debut of participants sleeping in unstable housing was 14.03 (SD = 2.11), compared to 14.71 (SD = 2.03) in those who did not sleep in unstable housing conditions (p = 0.014). For those who lived in unstable housing, the mean age of sexual debut was 13.98 (SD = 2.17) compared to 14.76 (SD = 1.99) in those who were not living in unstable housing (p < 0.001). To further elucidate the role of onset of sexual behaviors in relation to housing instability, we examined the debut of specific behaviors. Table 3 summarizes the age of sexual debut by each specific sexual act and shows the initial age of mutual masturbation and performing oral sex and anal sex (both insertive and receptive). Across almost all sexual behaviors, a younger age was associated with both living and sleeping in unstable housing.

In the final multivariable model for sleeping in unstable housing (Table 4), the odds of reporting sleeping in unstable housing conditions were higher among those who experienced lack of basic needs as a child 1–10 times (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.52, 95 % CI 1.11, 5.72) and even higher for those who experienced this more than 10 times (AOR = 5.47, 95 % CI 1.82, 16.45), whereby being enrolled in school is protective (AOR = 0.32, 95 % CI 0.18, 0.58). With regard to living in unstable housing, those who had a lifetime arrest history (AOR = 1.99, 95 % CI 1.15, 3.44) and experienced physical abuse as a child (1–10 times; AOR = 1.92, 95 % CI 1.10, 3.36, and more than 10 times; AOR = 3.51, 95 % CI 1.85, 6.09) were more likely to have lived in unstable housing. Additionally, those who had a lower perceived familial SES were more likely to live in unstable housing compared to those from the middle and upper class (lower AOR = 1.67, 95 % CI 0.93, 3.03, middle; AOR = 0.85, 95 % CI 0.46, 1.59). Being enrolled in school (AOR = 0.32, 95 % CI 0.18, 0.55) and self-rated health (very good; AOR = 0.73, 95 % CI 0.40, 1.34 and good/fair/poor; AOR = 0.51, 95 % CI 0.30, 0.89) were inversely associated with living in unstable housing.

Discussion

Our findings from this diverse cohort study of sexual minority men provide strong evidence that there are several factors associated with unstable housing in this population. Sexual minority men face more physical and mental health challenges than their heterosexual counterparts throughout the course of their lives, which may predispose individuals to these unstable housing states.26 , 27 Many studies on this topic explore the similarities and differences between heterosexual and homosexual youth,6 , 9 , 28 whereas this sample consisted of sexual minority men exclusively which may help guide more effective interventions.

Our data indicate that both childhood- and familial-based environments are salient factors related to the housing status of sexual minority men. Similar to Whitbeck et al., we found instances of childhood neglect, namely experiencing lack of basic needs from their parent(s) or other adult caregiver(s) increased the odds of sleeping in unstable housing.10 Physical abuse from a parent or other adult caregiver also increased odds of living in unstable housing. Additionally, reporting poorer self-rated health increased the odds of living in unstable housing conditions and, as prior evidence suggests, being unstably housed can increase negative health behaviors and outcomes. Furthermore, Rosario and colleagues also indicate earlier sexual debut among those who are unstably housed.2 In effect, housing instability may be viewed as one of several diminished health states imparted by these early life experiences.

Of the factors examined in our model, only one demonstrated protective associations. Those who were currently in school had lower odds of being unstably housed compared to those who were not, similar to what has been demonstrated in past research. O’Malley and colleagues examined whether family structure (including one- and two-parent households, foster care, and homelessness) and academic achievements moderated the effect of students’ perceptions of school climate.29 Their findings suggest that students who lack structure at home but rather obtain it from a supportive school environment achieve more than students who do not have a positive school climate29 Having access to counselors, social workers, teachers, or other trusted adults and an overall positive school climate might help prevent potentially adverse housing circumstances.

A key strength of our study is a more nuanced approach to examining housing instability by assessing both sleeping and living situations. As indicated previously, homelessness and housing states are assessed through several different mechanisms and they are often looked at with an either-or approach. By looking at a spectrum of unstable housing circumstances, we can begin to tease out the different experiences that may indicate sleeping in unstable housing and living in unstable housing, distinctly. Furthermore, sleeping in unstable housing may, for some young sexual minority men, be a precursor for living in unstable housing/homelessness, so understanding these nuances will undoubtedly aid in developing services and programming tailored to those most at risk.

Limitations

Prior to drawing final conclusions, limitations should be noted. First, this is a cross-sectional analysis that examines housing stability at one point in time, and thus, a causal relationship cannot be ascertained. A future analysis examining a change in housing status over time is warranted to try and decipher directionality between sleeping and living in unstable housing and not being unstably housed. This future research could examine the different aspects of housing instability assessed in the current study, which we did not have power to disaggregate in models. Second, non-probability recruitment methods were utilized, so this sample may not be generalizable to the larger population of sexual minority youth. Third, all data collected was self-reported and as such is subject to socially desirable reporting. Participants may be more likely to underestimate or not recognize their instances of housing instability and inversely have overestimated age of sexual debut, but the use of the ACASI technology minimizes these concerns.30 Because the parent cohort study was not designed specifically to examine housing stability, a limited number of variables with which to investigate the associations are available—for example, there were no measures addressing why participants had been unstably housed. Finally, as in all observational research, residual confounding is likely to be an issue.

Conclusions

The findings of our investigation are consistent the theory of syndemics which notes the interconnectedness of health states and the psychosocial stressors that drive these states in sexual minority men.31 In this study, we propose that understanding how mental, physical, and social health, which may include housing instability, relate to one another is critical to developing holistic services and programs to help combat negative health effects experienced by sexual minority men.19 More importantly, this theory provides a lens through which to examine the psychosocial drivers that predispose sexual minority individuals to higher rates of HIV,32 substance use,33 violence,34 and housing instability, among other interconnected health challenges, with the potential to develop holistic, all-encompassing interventions.

The findings of our analyses also lend themselves to important and salient recommendations for future policies and programming. There is a demonstrated need to increase funding for LGBTQ-focused homeless service providers/agencies because almost one fifth of our sample were unstably housed.7 , 35 Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence-based interventions for providers working with SMY.11 Continued re-authorization of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (RHYA), the existing federal legislation that funds drop-in centers, street outreach programs, and basic needs for homeless youth, is also essential.11 , 36 Access to counselors, social workers, and other school-based resources may contribute to why educational status is a protective factor in this population. Training educators and school-based officials on best practices for working with young sexual minority men and utilizing school-based resources (e.g., LGBT Centers and gay-straight alliances) reduce housing instability. Because parents also play pivotal roles in the lives of children throughout their developmental trajectory, structural interventions with parents around issues of sexuality can protect against housing instability.11 , 37 – 39 Finally, recognizing the distinctions between housing states and intervening early may help prevent progression from housing instability to homelessness.

References

Lolai D. You’re going to be straight or you’re not going to live here: child support for LGBT homeless youth. Tul JL & Sexuality. 2015; 24: 35.

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Risk factors for homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a developmental milestone approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012; 34(1): 186–93.

Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010; 31: 457–77.

Van Leeuwen JM, Boyle S, Salomonsen-Sautel S, et al. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: an eight-city public health perspective. Child Welfare. 2006; 85(2): 151–70.

Quintana S, Rosenthal J, Kehely J. On the streets: the federal response to gay and transgender homeless youth. Washington DC: Center for American Progress (CAP); 2010.

Corliss HL, Goodenow CS, Nichols L, Austin SB. High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative Massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health. 2011; 101(9): 1683–9.

Durso LE, Gates GJ. Serving our youth: findings from a national survey of service providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund; 2012.

Kipke MD, Weiss G, Wong CF. Residential status as a risk factor for drug use and HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2007; 11(6 Suppl): 56–69.

Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92(5): 773–7.

Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Tyler KA, Johnson KD. Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. J Sex Res. 2004; 41(4): 329–42.

Keuroghlian AS, Shtasel D, Bassuk EL. Out on the street: a public health and policy agenda for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014; 84(1): 66–72.

Gattis MN. An ecological systems comparison between homeless sexual minority youths and homeless heterosexual youths. J Soc Serv Res. 2013; 39(1): 38–49.

Frederick TJ, Ross LE, Bruno TL, Erickson PG. Exploring gender and sexual minority status among street-involved youth. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2011; 6(2): 166–83.

Zerger S, Strehiow AJ, Gundlapalli AV. Homeless young adults and behavioral health: an overview. Am Behav Sci. 2008; 51(6): 824–41.

Marshall BD, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, Wood E. Survival sex work and increased HIV risk among sexual minority street-involved youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010; 53(5): 661–4.

Walls NE, Bell S. Correlates of engaging in survival sex among homeless youth and young adults. J Sex Res. 2011; 48(5): 423–36.

Brown MJ, Masho SW, Perera RA, Mezuk B, Cohen SA. Sex and sexual orientation disparities in adverse childhood experiences and early age at sexual debut in the United States: results from a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2015; 46: 89–102.

Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Siconolfi DE, et al. Individual, psychosocial, and social correlates of unprotected anal intercourse in a new generation of young men who have sex with men in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103(5): 889–95.

Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Storholm ED, Solomon TM, Bub KL. Measurement model exploring a syndemic in emerging adult gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013; 17(2): 662–73.

Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav. 2005; 9(3): 251–65.

Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WR, Martin CE. Sexual behavior in the human male. 1948. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93(6): 894–8.

Duncan DT, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Examination of spatial polygamy among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New York City: the P18 cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014; 11(9): 8962–83.

Halkitis PN, Figueroa RP. Sociodemographic characteristics explain differences in unprotected sexual behavior among young HIV-negative gay, bisexual, and other YMSM in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013; 27(3): 181–90.

Moreira AD, Halkitis PN, Kapadia F. Sexual identity development of a new generation of emerging adult men: the P18 cohort study. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2015; 2(2): 159–67.

Harris KMU, J. R. Wave III codebooks. The National Longitudinal Study of adolescent to adult health. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/codebooks/wave3. Accessed 12 Sep 2015.

Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Weiss G, et al. Original article: the health and health behaviors of young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2007; 40: 342–50.

Lock J, Steiner H. ARTICLES: gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth risks for emotional, physical, and social problems: results from a community-based survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999; 38: 297–304.

Kipke MD, Simon TR, Montgomery SB, Unger JB, Iversen EF. Homeless youth and their exposure to and involvement in violence while living on the streets. J Adolesc Health. 1997; 20(5): 360–7.

O’Malley M, Voight A, Renshaw TL, Eklund K. School climate, family structure, and academic achievement: a study of moderation effects. Sch Psychol Q. 2015; 30(1): 142–57.

Langhaug LF, Sherr L, Cowan FM. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2010; 15(3): 362–81.

Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Millett GA. A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Am Psychol. 2013; 68(4): 261–73.

Halkitis PN. Reframing HIV, prevention for gay men in the United States. Am Psychol. 2010; 65(8): 752–63.

Salomon EA, Mimiaga MJ, Husnik MJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, utilization of mental health care, substance use and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men in EXPLORE: implications for age-specific interventions. AIDS Behav. 2009; 13(4): 811–21.

Stall R, Friedman M, Catania JA. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, eds. Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Choi SK, Wilson BDM, Shelton J, Gates G. Serving our youth 2015: the needs and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth experiencing homelessness. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund; 2015.

Runaway and homeless youth program authorizing legislation. In: Bureau FaYS, ed. Vol 110–378. Washington DC; 2012.

Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E. Sexual health information seeking online among runaway and homeless youth. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2011; 2(2): 88–103.

Rice E, Monro W, Barman-Adhikari A, Young SD. Internet use, social networking, and HIV/AIDS risk for homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010; 47(6): 610–3.

Mayer KH, Garofalo R, Makadon HJ. Promoting the successful development of sexual and gender minority youths. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104(6): 976–81.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Contract no. R01DA025537.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, K.D., Kapadia, F., Ompad, D.C. et al. Early Life Psychosocial Stressors and Housing Instability among Young Sexual Minority Men: the P18 Cohort Study. J Urban Health 93, 511–525 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0049-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0049-6