Abstract

This article analyzes the subjective well-being and life satisfaction of 1033 Chilean children (507 girls and 526 boys) aged 9 to 14 years (M = 11.02, SD = 1.18) living in the socio-economic state of poverty. Different subjective well-being scales were administered to assess both affective and cognitive components, be they context-free or different domains of life satisfaction, including the use of free time. A structural equation modelling was put to the test measuring to what degree the various components of well-being were correlated to a second order latent variable showing good fit. Later, the general results returned middle high scores on these scales with significant differences found by gender, especially for affective and overall life satisfaction components. Boys displayed higher overall subjective well-being scores than girls. These differences were less evident when assessing the subjective well-being in specific domains; the boys’ and girls’ scores were closer here. These results are discussed along with their contributions toward understanding subjective well-being in childhood as a complex, multi-faceted concept. These findings may turn out to be particularly interesting when it comes to designing and evaluating public policies geared toward children by providing evidence that supports the inclusion of socio-emotional and relational variables in the promotion of improved quality of life for children living in poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Subjective Well-Being of Children and Adolescents

Children’s self-assessment of their own well-being has been studied in the last several years. This particular interest in the well-being of children and adolescents is manifest in a large number of scientific articles, book chapters and academic texts, including a Handbook (Ben-Arieh et al., 2014; Casas et al., 2014; Cummins, 2014; Rees, 2021). The prior standard approach presented the perceptions, opinions and ways of understanding children’s lives through an adult perspective. These were used by governments, institutions and professionals (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020) to make decisions about childhood. The new focus is on collecting and trusting the data gleaned directly from children without any adult interpretation or mediation, also known as an adult-centric viewpoint. This new approach has been recently substantiated by increased research into children’s opinions that has clearly displayed the differences in perceptions between adults and children (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020).

Another interesting change is the incorporation of a positive perspective into the study of childhood. As is the case with the majority of the human and social sciences, when one reviews the overall history, a large part of the contributions in the fields of psychology or mental health have been done with a scarcity mindset or by contemplating the problems/illnesses of individuals and communities. Only recently in the last couple of decades it has been seen publications with a positive perspective in terms of development and promotion. Topics like children’s participation and subjective well-being have experienced a renewed push, having drawn the attention of researchers and academics (Casas, 2011).

This research perspective into children’s subjective well-being has not been free from debate. One of the most sensitive issues has been whether or not children should be viewed as reliable informants of their own well-being. The findings and scientific evidence have supported their contribution, which is now getting some consideration by those responsible for creating public policy (Bradshaw et al., 2017; Casas et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2017). The Convention on the Rights of the Child as well as increasing study and research into childhood give support to the idea that children are persons with rights, thus they are also actively involved in their own development. Progress has recently been made around the consensus view that determining childhood well-being is in fact not possible without directly asking children to assess their own lives (Bradshaw & Richardson, 2009; Casas et al., 2013; Mullender et al., 2002).

Subjective well-being refers to how people evaluate their own lives both in general terms as well as specific life domains such as the family, friends and free time (Ben-Arieh et al., 2014). Subjective well-being is often divided into cognitive (satisfaction with life overall and specific domains) and affective (positive and negative) components (Campbell et al., 1976; Diener, 1984). Research has shown that positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction are three interrelated components that comprise subjective well-being (Lucas et al., 1996). Although both affect and life satisfaction are connected in the sense that they imply making judgments about life circumstances, they can also be differentiated. While affect is defined in terms of emotional responses, life satisfaction is expressed cognitively. Life satisfaction, which can be indirectly influenced by affect, is for the most part defined as an evaluative response to life in its entirety or in regard to specific domains of life such as the family, friends or school (Diener, 1984).

Considering multiple domains as well as overall life satisfaction can help facilitate a more precise understanding of subjective well-being, which may help in designing better focused intervention programs. For example, a child or group of children that present lower satisfaction scores in the domains of school or classmates would need a different intervention than a child or group of children who indicate having less satisfaction in the family sphere. The research of Seligson et al. (2005) shows that the domains of greatest impact on overall life satisfaction for children and adolescents include family, friends, school, their surroundings and satisfaction with self.

Another important domain of well-being that has been studied and identified is the use of time. Children’s well-being seems connected to the ways in which they occupy their time. The time use factor can give us information about their opportunities for acquiring and applying skills that are essential for well-being (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020). Until today, however, the large majority of such research has been done in high-income countries. This means there are substantial gaps in understanding in this regard in countries with greater levels of social vulnerability (Rees, 2018).

From a theoretical point of view, the Bronfenbrenner (1987) ecological model is one of the more relevant proposals regarding the study of subjective well-being, given that it integrates different levels of context in a process of bidirectional and systemic interactions (Bedin & Sarriera, 2014; González-Carrasco et al., 2019; Lawler et al., 2017). The empirical evidence attests to the importance of including contextual variables in the study of subjective well-being (Gilman & Huebner, 2003; Oyarzún Gómez, 2016). These latter authors suggest that life satisfaction can be better explained if indicators are included from the various systems and micro-systems that are involved in children’s development, such as the social and family context.

The creation of psychometric instruments to assess subjective well-being in child and teen populations has helped gather rich information and evidence. This in turn has amplified the interest of a range of disciplines in studying this subject, including sociology, psychology, education, and economics (Oliveros Werner, 2015; Oyanedel et al., 2014). This is how subjective well-being has become a topic of interest at the international level, which has enabled very rapid progress in recent years. This has decreased the gap in study results between adult and child populations. The systematic work of the Children’s Worlds project with its three waves of studies comparing countries in terms of childhood subjective well-being has created new evidence-based knowledge, improved assessment tools and indicators, and also enabled collaboration to better understand children’s lives, their subjective well-being, and use of time (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020). This has subsequently demonstrated the validity of the scales used in measuring children’s life satisfaction in a comparative international context (Casas & Rees, 2015; Casas, 2017). Research in Chile has progressively advanced in the study of subjective well-being in childhood. The first publications began in the 2000s (Farías Olavarría et al., 2015), primarily in the adult population. Interest in childhood publications has gradually increased in Chile. Participation in the international study of Children’s Worlds, in addition to the lines of research that have been developed in different regions of the country, provide information about the SWB of children in Chile (Alfaro et al., 2015; Álvarez & Briceño, 2016; Oyanedel et al., 2015; Alfaro Inzunza et al., 2013; Oyarzún et al., 2019; Rees, 2021; Reyes Reyes et al., 2019).

Factors Affecting children’s Subjective Well-Being

Available findings have shown that children in general have a high level of overall subjective well-being. In most cases they are satisfied with their lives at present and with what they expect may happen to them in the future (Rees, 2021). A small percentage of children, however, do present lower levels of well-being, which serves as a warning indicator for those who care for them.

The data on hand have shown that life satisfaction tends to decrease around the ages of 10 to 16 in most countries (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2019; Žukauskienė, 2014; Shek & Li, 2016).

Children’s Subjective Well-Being and Socioeconomic Levels

Economic situations are often associated with children’s subjective well-being even when findings are inconsistent. Some results demonstrate a significant connection between financial status measured by income and subjective well-being (Gross-Manos, 2017; Rees et al., 2011; Saunders & Brown, 2020; Sarriera et al., 2015), whereas others are not conclusive (Carlsson et al., 2014; Knies, 2011).

A recent study done by Rees (2021) based on the results of the third wave of Children’s Worlds that compared 35 countries in terms of children’s well-being and levels of overall satisfaction for various domains of their lives concluded that there are significant differences in well-being depending upon material circumstances. Those with fewer material resources than the average tended to have a significantly lower level of well-being than those children with more resources than the average. Results such as these were obtained in several measures of general well-being and satisfaction with a number of life domains in samples from Brazil, Chile and Spain. These findings are consistent with other comparative studies (Dinisman & Ben-Arieh, 2016).

One potential reason why there is variation in research outcomes is that household income, which is a commonly used poverty measure, cannot precisely or consistently represent the real life experience of children. It has been observed that their subjective well-being weakly correlates with objective poverty levels, which can be viewed as adult-centric measurements (Knies, 2011; Main, 2019; Rees et al., 2011). Empirical results have suggested that family relationships and friendships may mediate or moderate the connection between poverty and the subjective well-being of children. Good family relationships may prevent more extensive declines in subjective well-being (Cho, 2018).

The conclusions of studies conducted so far concur with the idea that further research is needed, especially in less wealthy countries and in areas with greater socioeconomic risk (Rees, 2021).

Subjective Well-Being and Differences by Gender

Various studies have looked at the differences in the subjective well-being of children according to gender. The evidence so far is inconclusive. While some studies have found no significant differences (Sarriera et al., 2012; Huebner et al., 2006), other findings report differences in the subjective well-being between girls and boys (Bradshaw et al., 2011; Chui & Wong 2016; Dinisman et al., 2013; Dinisman & Ben-Arieh, 2016; Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017; Llosada Gistau et al., 2020). Some have suggested that such differences may be even more evident when particular domains of subjective well-being are focused on. For example, some studies conclude that girls tend to have higher levels of subjective well-being when it comes to interpersonal relationships (Bradshaw et al., 2011; Ma & Huebner, 2008). For girls, relationships with classmates and family members as well as satisfaction with oneself seem to have greater impacts on their subjective well-being compared to boys. Some authors conclude that girls’ subjective well-being seems to be affected by social relationships, while boys’ subjective well-being is more closely associated with measures of success connected to achievement, such as performance at school. This may be related to the traditional gender socialization differences between girls and boys (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017).

One study that used data from the Children’s Worlds third wave that compared subjective well-being in countries on different continents found differences between the girls’ and boys’ results depending upon their ages. At ten years of age relatively few differences by sex were found for the children’s subjective well-being. The main exception was that girls in many countries said they felt more satisfied with aspects of school life. At 12 years of age the boys were showing a slightly better well-being level than the girls. This was more pronounced regarding satisfaction with one’s own appearance. In Brazil, Chile and Spain, boys had a significantly higher degree of satisfaction with their appearance than the girls in this age group (Rees, 2021). These longitudinal studies have shown a crossed effect between age and sex between 10- to 16-year-olds. The girls start out with higher scores but end up with significantly lower ones due to the higher speed with which positive affect decreases and negative affect increases for them compared to the boys (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2020).

Other studies on Chilean children evaluating their global life satisfaction have shown significant differences between girls and boys, with boys displaying higher scores (Céspedes Carreño et al., 2019; Reyes Reyes et al., 2019). These gender differences are still observed when analysing separately native Chilean children and migrant children residing in Chile, whose majority origin has been from Latin American countries (Céspedes Carreño et al., 2019).

Child Well-Being and Poverty

In Chile a large percentage of the child population is living in poverty with high rates of social vulnerability and fewer opportunities for comprehensive development. Around one third of the child population (30.4%) lives in housing with unaddressed needs as shown by indicators of housing type, material structure, access to potable water and crowding (Centro Iberoamericano de Derechos del Niño, 2019). Multidimensional poverty indicators measured in Chile show that 22.9% of the child and teen population live in poverty (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, 2020). While progress on poverty reduction has been made in recent decades, a serious problem remains for a significant number of children and adolescents. Most studies that address this target group have focused solely on scarcity and setbacks, so there is scant evidence that depicts their levels of well-being. This means little information is available to guide decision-makers in creating programs and setting priorities in terms of public policies and initiatives (Alfaro-Inzunza et al., 2019; Bilbao et al., 2020; Contreras et al., 2015).

This Study

The purpose of this article is to contribute to the scientific understanding of the subjective well-being and life satisfaction of school-age Chilean children living in poverty. The specific objectives include:

-

a) Assessing the subjective well-being and overall life satisfaction of children living in conditions of high social risk.

-

b) Comparing children’s subjective well-being according to their gender

In addition to the research objectives, we will discuss the ways in which these findings contribute to the design of evidence-based interventions to promote the subjective well-being of children living in situations of high social vulnerability.

Method

Participants

The sample is comprised of 507 girls and 526 boys totaling 1033 children. Their ages are ranged between 9 and 14 years (M = 11.02, SD = 1.18). Of the total, 919 (89%) live in urban areas and 114 in the rural parts (11%) of the Metropolitan Region of Chile. According to their nationality, 841 are Chilean (81.4%) and 192 are foreigners (18.6%). Data collection was carried out between May and December 2019.

All the children and adolescents were socioeconomically situated in poverty in accordance with the Educational Vulnerability Index used in Chile (IVE-SINAE in Spanish). The IVE-SINAE is a socioeconomic indicator calculated every year by the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships public service (JUNAEB in Spanish). The IVE-SINAE ranges from 0 to 100%. Higher numbers indicate increased vulnerability levels. This indicator expresses the poverty risk status associated with the children in each school (Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas, JUNAEB, 2020). The children in the sample attended schools that had an average IVE in the quintile with the greatest amount of social vulnerability at 88.12%.

Instruments

The study included psychometric scales of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and use of free time that are used internationally and were validated in Chile by prior research (Alfaro et al., 2016; Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020; Rees, 2021).

-

1.

The Children’s Worlds Positive and Negative Affect Scale (CW-PNAS). It measures the affective component of subjective well-being and is based on the Core Affect Scale (Russell, 2003; Feldman Barrett & Russell, 1998). Just as the earlier scales, this version is part of the third wave of Children’s Worlds.Footnote 1 The instructions state: Check the box that best describes how you have felt over the last two weeks. It has an 11-point response range in which 0 means “I never feel like this” and 10 means “I always feel like this”. Positive affect are included such as happy, calm, and full of energy. Negative affect are included such as sad, stressed and bored (see Table 3). With this sample, the CW-PNAS affective scale presented a good fit considering the six items (χ2 = 13.311; CFI = 0.997; RMSEA = .047; SRMR = .009). The reliability for the positive and negative effects is moderate (α = .54 y α = .63, respectively).

-

2.

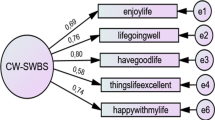

Children’s Worlds Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-SWBS). This scale measures the context-free cognitive dimension of subjective well-being. It was designed based on the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale - SLSS (Huebner, 1991), validated in Chile by Alfaro et al. (2016). This is a new version that was improved to make it more interculturally comparable in the spirit of the third wave of the Children’s Worlds international study (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020). The wording is Please say how much you agree with each of the following sentences about your life as a whole. According to Casas and González-Carrasco (2021), the CW-SWBS did not fit well enough with the original six items but displayed an excellent fit with five items and they recommended to use that version (CW-SWBS5) (χ2 = 13.311; CFI = 0.997; RMSEA = 0.047; SRMR = 0.009). It includes the items: “I enjoy my life”, “My life is just as it should be”, “The things that happen in my life are excellent”, “I like my life”, “I am happy with my life”. The response scale format was an 11-point Likert type scale with values ranging from 0 for “Not at all agree” up to 10 for “Totally agree” and its reliability was (α = .91).

-

3.

The multidimensional Children’s Worlds Domain Based Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-DBSWBS) measures the cognitive dimension of subjective well-being assessed via satisfaction with different domains of life. It was created taking the Brief Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) of Seligson et al. (2003). The version used in this study was the one modified by Casas and Rees (2015) and validated in Chile (Alfaro et al., 2016). The wording is How satisfied are you with …The 11-point scale runs from 0 to 10 in which 0 means “Not satisfied at all “ and 10 is “Totally satisfied”. The CW-DBSWBS scale presents an optimal fit for the sample using five items (χ2 = 13.549; CFI = 0.988; RMSEA = 0.041; SRMR = 0.021). It includes the items: “Satisfaction with your friends”, “Satisfaction with the area where you live”, “Satisfaction with your family”, “Satisfaction with your life as a student”, “Satisfaction with the way that you look”. The reliability of the scale for the sample was α = .67.

-

4.

Items regarding the use of free time based on those used in the Children’s Worlds project, including two items on satisfaction with the use of time. Satisfaction was measured with a 11-point scale, where 0 is “Not satisfied at all” and 10 “Totally satisfied”. The items are: “how do you use your time” and “the amount of free time you have to do what you want”

-

5.

Overall Life Satisfaction Scale (OLS) has a single cognitive SWB item. The OLS evaluates overall life satisfaction as proposed by Campbell et al. (1976). The OLS has shown sufficient validity concordant with other school satisfaction measures for Chilean, Brazilian, Spanish, and Romanian students (Casas et al., 2015a, b). The 11-point scale runs from 0 to 10 and asks: How satisfied are you with your life as a whole?

Procedure

A pilot study was done during November 2018 with children to observe how they view the questions and the length of the survey. Afterward the definitive version of the questionnaire was finalized.

The sample drew from 60 schools located in high-risk areas of different neighborhoods in the Metropolitan Region. The sample included schools in 31 out of 52 communes that make up the Metropolitan Region.

Data collection was done during the 2019 school year between May and December. Each school was contacted, and they formally authorized the survey application at an agreed upon time and date. Informed consent forms for the children’s parents or guardians were delivered to the schools. Children whose parents did not authorize the use of the questionnaire were given an alternate activity while the others answered the survey. The research term was present in person to administer the scales to the group.

Data Analysis

Any questionnaires that left 25% or more of the answers unaddressed were excluded. Each scale was subsequently analyzed and any forms that had 25% of more of answers left blank for a given scale were also excluded. Out of the 1099 children who participated, 66 questionnaires were eliminated, so the final sample size was 1033 children. Once the database was refined, the missing values were imputed by regression with the SPSS 21 software.

With the maximum likelihood method in the Amos 21 software, a Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to test a second order model, incorporating affective and cognitive measures of well-being: the positive and negative affect components (CW-PNAS) and the general context-free (CW-SWBS) and by domains (CW-DBSWBS) cognitive components. In keeping with the criteria used in an analysis done by Casas et al. (2015a, b), a subjective well-being model with a sample of children and adolescents from three countries (Spain, Brazil, and Chile) was then used to verify the validity of its factorial structure. The chi-squared test, Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Steiger-Lind Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were used as fit indices of the model. Values greater than .95 on the CFI and lower than .05 on the RMSEA and SRMR were viewed as having excellent fit (Arbuckle, 2010; Byrne, 2010).

Squared Multiple Correlations (SMC) were calculated for each model because they indicate how accurately each variable is predicted by the other variables in the model (Arbuckle, 2010; Byrne, 2010). Each SMC value is an estimate from the lower band of reliability relating to its variable (Arbuckle, 2010; Byrne, 2010).

Next the model was tested with multigroup analysis by sex in order to determine if the parameters of the psychometric instruments were invariant for both groups, thus comparable in their scores. Three levels of invariance were tested: (a) configural invariance (model without constrains), (b) metric invariance (factor loadings constrained), and (c) scalar invariance (factor loadings and intercepts constrained). The metric invariance enables a comparison of correlations and regressions while the scalar invariance allowing means comparison. The measurement invariance was acceptable if upon adding each new restriction a change in CFI of less than .01 was observed (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Once the factorial structure of the model was checked, descriptive statistics and t-tests between gender were calculated. The overall index for each scale is presented in a range of 0–100 to facilitate visual comparison.

Ethical Aspects

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out by the Universidad de Girona in the Doctoral Program in Psychology, Health and Quality of Life for research on people as well as the protocols for ethical research that guides scientific studies in Chile (CONICYT/FONDECYT, 2008). School directors were contacted and formally invited to participate, who then authorized the application of the questionnaire, which was registered in a signed document. The children’s parents or legal guardians were asked to sign the consent form that had been sent to them before to the survey was conducted. Informed consent was requested of the children through a document that explained that study participation was voluntary, their responses would remain anonymous and strictly confidential, and the information would be used solely for the purposes of this research.

Results

Structural Equations Modelling

The integrative model, which was designed to incorporate affective and cognitive components that include context-free aspects as well as particular domains of satisfaction, showed an optimal fit (χ2 = 293,454; CFI = 0.966; RMSEA = 0.044; SRMR = 0.034. The model incorporates four latent variables that correspond to each of the utilized psychometric scales, which in turn are related to a second-order latent variable. Analysis of modification indexes suggested how to improve the fit of the model by excluding one of the items of the CW-SWBS5 and by adding two error covariances, which in fact are very low (<.2) and therefore do not suggest any serious overlapping, so both items are kept in the model in both cases.

Specifically, the four items from the CW-SWBS included were “The things that happen in my life are excellent”, “I like my life”, “I enjoy my life”, “I am happy with my life”. The full affect scale, CW-PNAS, was included, the three items from the positive affect scale and the three items from the negative affect scale (“you feel happy”, “you feel calm”, “you feel full of energy”; and “you feel sad”, “you feel stressed”, “you feel bored”).

The items concerning satisfaction with the use of time were tested as related to the CW-DBSWBS latent variable to assess whether or not they made a unique contribution that increased the fit of the model. Previous to include them in the model, a multiple linear regression was done with the OLS scale as a dependent variable in keeping with the criteria established by the International Wellbeing Group (2013). Satisfaction with time use showed a contribution of 2.5% with unique explained variance. Then the structural equation model was revised by excluding the item on satisfaction with the amount of free time, as it provided no unique variance (see Supplementary materials). Therefore, in this model six items have been related to a latent variable named CW-DBSWBS: satisfaction with your friends, with the area where you live, with your family, with your life as a student, with the way that you look, and with how you use your time. This version of the CW-DBSWBS including the satisfaction with time use item presented an excellent fit (χ2 = 24.911; CFI = .982; RMSEA = .041; SRMR = .025) and its reliability was α = .70.

Figure 1 shows this model displays an excellent fit (χ2 = 293.454, gl = 97, p < .001; CFI = .966; RMSEA = .04 [.039–.050 with 90% CI)]; SRMR = .034). According to the SMC scores the explained variance of the second order latent-variable on each first-order latent variable is of 76% for the CW-SWBS, of 74% for the CW-DBSWBS, of 86%for the Positive Affect, and of 27% for the Negative Affect.

The results of the multigroup analysis by gender are shown in Table 1, displaying that the model achieved metric and scalar invariance. This suggests that the correlations, factorial loadings and means can be compared between boys and girls.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Using the total sample, the results show that the participants had medium high scores for the well-being scales with values of skewness and kurtosis within acceptable rangesFootnote 2 (Kline, 2015). Means for the OLS, CW-SWBS, DBSWBS and positive affect scales returned high scores with more than 80 points out of 100, whereas the negative affect average was low (see Table 3).

For the affect scales, the item with the highest scores was “you feel happy”. Regarding the Children’s Worlds (CW-SWBS) context-free scale, the item with the highest scores was “I’m happy with my life”. The highest scoring item on the CW-DBSWBS scale that measures the cognitive dimension of subjective well-being assessed through satisfaction with different domains of life was “satisfaction with the family”.

The correlations were calculated to assess the association between the subjective well-being scales. The correlations among the positive measures ranged between r = 0.364 and r = 0.703 (p < .001), with all of them being statistically significant, i.e., the higher the score on the well-being scales, the higher the score on the others, including the positive affect scale. The negative affect scale negatively correlates to the other scales, with all of them being statistically significant. The values range from r = −0.215 and r = −0.351 (p < .001); i.e., the higher the score on the well-being scales, the lower the score on the negative affect scale (see Table 2).

Comparing the Scores of the Subjective Well-Being Scales and Items by Gender

The scales and items were compared between the groups by sex using the t-test for independent samples. As shown in Table 2, the majority of the items on the well-being and life satisfaction scales report significant differences between girls and boys. The single-item OLS Overall Life Satisfaction scale and the CW-PNAS Children’s Worlds Positive and Negative Affect scale demonstrate differences by sex with statistical significance in that the boys had higher scores than the girls. The boys showed more subjective well-being than the girls for all positive and negative affect items except for one (You have felt calm). The boys said they were more satisfied with life, felt happier, had more energy, felt less sad, less stressed and less bored than the girls.

The boys had significantly different and higher scores on the context-free subjective well-being Children’s Worlds scale (CW-SWBS) (Girls: M = 85.12, SD = 22.22; Boys: M = 89.15, SD = 18.14). Different results were obtained with the CW-DBSWBS depending on the domain being assessed. The domain of greatest satisfaction was the family and the one with the lower satisfaction scores was in relation to the neighborhood. Differences between boys and girls were not significant, except for satisfaction with the family - boys displaying significantly higher scores than girls.

Discussion

The main aim of this article was to contribute to the scientific understanding of the subjective well-being and life satisfaction of school-aged Chilean children living in poverty. The study was conceptually based on an understanding of the subjective well-being of girls and boys that considers affective (positive and negative affect) and cognitive components (either context-free or considering different satisfaction domains). This is why information was collected in view of a number of scales that address these components based on evidence accumulated in several countries including Chile (Alfaro et al., 2016; Arthaud-day et al., 2005; Ben-Arieh et al., 2014).

An integrative model of subjective well-being was designed and tested in this study using SEM with the data provided by our sample – this model displaying an excellent fit. The model integrated affective and cognitive components, which provide empirical support to the tripartite theory considering three components of subjective well-being. These include a cognitive component referred to as the cognitive assessment with respect to life satisfaction at the overall level and in different domains. The second component is positive affect, and the third being negative affect (Arthaud-Day et al., 2005; Metler & Busseri, 2017). The array of components at the foundation of this subjective well-being construct has also been reported in earlier studies (Bedin & Sarriera, 2014; Casas, 2017; Strelhow et al., 2020).

A multiple regression analysis showed a relevant contribution with unique explained variance of an item on satisfaction with time use to an overall life satisfaction scale. This underscores the importance of including satisfaction with the use of time as a domain to consider when assessing subjective well-being, an analysis that was done with the model used in this study. Consequently, an item on satisfaction with time use was added to our model, and it was related to the cognitive domain-based latent variable.

The second order model tested in this study displayed excellent fit. Three of the four first-order latent variables showed very high explained variance from the second-order latent variable, as measured by SMC. Only the Negative Affect latent variable showed low SMC scores suggesting it is much less important to explain the core component of subjective well-being, than positive affect or the cognitive components. Such result is consistent with previous findings suggesting Negative Affect has lower correlations with cognitive components than positive affect (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2020).

Generally, in regard to the first objective, the child participants had high levels of subjective well-being and overall life satisfaction, which is in agreement with other studies’ results (Rees, 2021). Values greater than 80 points on a 0- to 100-point scale were obtained on all scales except for the negative affect scale, which had an average of less than 40. Considering the fact that all of the children who participated in this study live in highly vulnerable social conditions, the relatively high score averages for subjective well-being and overall life satisfaction observed herein strengthen proposals to distinguish the assessments of adults and children. Children’s subjective well-being appears to be affected differently by objective poverty levels than in the adult population (Bruck & Ben-Arieh, 2020; Main, 2019). As demonstrated in other studies, the quality of relationships maintained with other adults may mediate or moderate the effects of socioeconomic factors in children’s subjective well-being (Cho, 2018; Knies, 2011; Main, 2019).

These findings may turn out to be important for creating evidence-based public policies designed for children by indicating the essential utility of considering not only material variables, but socio-emotional and relational ones as well in order to help improve the quality of life of children living in poverty. From an academic standpoint, these results add to our understanding of the well-being level of children living in developing countries like Chile while helping to decrease the current disparity of studies undertaken in European, North American and Asian countries as compared to Latin America as a whole.

Regarding the second objective, important gender differences were observed for SWB scores, particularly in the affective components and in global life satisfaction - boys showing higher levels of well-being than girls. These results are consistent with those reported in other studies in Chile in which boys express being more satisfied with life than girls, even in the case of migrant children living in Chile (Céspedes Carreño et al., 2019) and consistent with results in other countries (Casas et al., 2013; Rees et al., 2011). The results of this study turn out to be worrying, in terms of the fact that girls showed on average a lower level of SWB than boys. In this regard, and considering an ecological systemic perspective, these results can be associated with existing gender gaps at the macrosocial level. As has been suggested by some authors (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017; Tesch-Römer et al., 2007), gender inequalities in the development of the country, as well as the presence of differentiated and stereotyped socialization patterns, may be important for understanding differences in SWB between girls and boys.

These differences were less evident when assessing SWB in specific domains, with more similar results being observed between boys and girls. The domain in which girls and boys were most satisfied with was family and the one with the least satisfaction was the neighborhood. There are studies in other countries that conclude that in the domain of relationships with others, for example, the SWB of girls is higher than that of boys (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017; Uyan-Semerci et al., 2017). In this study, the only domain in which boys had significantly higher levels of SWB was satisfaction with their families. These results contrast with those obtained in an international study that used data from the Children’s Worlds survey in which the subjective well-being of 12-year-old girls and boys was compared, noting that no gender differences were observed related to satisfaction with the family (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017). Upon reviewing the evidence so far, reports on this topic are not conclusive, which means more comparative studies are needed. In summary, the results of this research highlight the importance of considering gender as an outstanding analytical variable when it comes to the SWB of children living in vulnerable social conditions.

With respect to how these results can be incorporated into social interventions with children, we see a marked growing trend of integrating such empirical evidence into public policy and program design guidelines around childhood (UC Center for Public Policies, 2017; Chaves & Ramírez, 2020; UNICEF, 2018). Studies on subjective well-being have supported the formulation of public initiatives that bear in mind the children’s own opinions as active citizens and social agents involved in the very matters that affect them. This fulfills one of the rights inscribed in the Convention on the Rights of the Child that was ratified by most countries around the world (Cabieses et al., 2020).

Additionally, Chile has committed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development agreed upon in 2015 by the international community within the framework of the United Nations General Assembly (Asamblea General de Naciones Unidas, 2015). This new development agenda proposes 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) and 169 targets, some of which directly impact children’s lives. The SDGs lay out broad-based challenges such as bringing at least half of children and teens out of poverty, ensuring that all of them can access quality education, eliminating all forms of violence against children and adolescents, and more.

The results of this study lend conceptual and methodological support to the idea that the construct of child well-being is quite multi-faceted. Various aspects such as these must be considered when designing programs and initiatives aimed at promoting well-being and quality of life for children who live in poverty and experience social exclusion.

An orientation toward evidence-based social program design has been more evident in so-called developed countries where it is part of social policy in some places. Knowledge production, data generation and a systematization of best practices are a few of the strategies that will help produce the inputs needed for designing innovative, quality and high-impact policies and programs. The challenge still remains to make progress on integrating such well-being indicators in Latin American countries, as is the case of Chile.

The results of this study have some limitations. One is that the sample only included children living in poverty, so the conclusions are restricted to this specific group in Chile. At the same time, the sample considered only girls and boys in the Metropolitan Region, so these results cannot be generalized to other regions of the country, which due to their diverse characteristics could yield different results. Thus, for example, in the Descriptive Report of Chile of the third wave of the Children’s Worlds research: International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB), differences in life satisfaction were observed for different domains between children from the Metropolitan Region and the Bío-Bío Region (Centro de Investigación en Complejidad Social & Centro de Estudios en Bienestar y Convivencia Social, 2021). Future research should consider the inclusion of other socioeconomic groups, as well as the participation of boys and girls from other regions of the country. Furthermore, expanding the sample to include children in other Latin American countries may further elucidate the analysis of the effects of material conditions and poverty on children’s SWB.

Change history

03 December 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10001-3

Notes

Project website: www.isciweb.org

The ranges of skewness and kurtosis are considered to be problematic for the distribution when the values are greater than 3 for skewness and above 10 for kurtosis (Kline, 2015).

References

Alfaro, J., Casas, F., & López, V. (2015). Bienestar en la infancia y adolescencia. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://www.psicoperspectivas.cl/index.php/psicoperspectivas/article/view/601.

Alfaro, J., Guzmán, J., Reyes, F., García, C., Varela, J., & Sirlopú, D. (2016). Satisfacción Global con la Vida y Satisfacción Escolar en Estudiantes Chilenos. Psykhe, 25(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.25.2.842

Alfaro Inzunza, J., Valdenegro Egozcue, B., & Oyarzún Gómez, D. (2013). Análisis de propiedades psicométricas del Índice de Bienestar Personal en una muestra de adolescentes chilenos. Diversitas: Perspectivas En Psicología, 9(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-9998.2013.0001.01.

Alfaro-Inzunza, J., Ramírez-Casas Del Valle, L., & Varela, J. J. (2019). Notions of life satisfaction and dissatisfaction in children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status in Chile. Child Indicators Research, 12(6), 1897–1913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9618-4

Álvarez, V., & Briceño, A. M. (2016). Calidad de Vida, Bienestar y Felicidad en Niños y Adolescentes: una aproximación conceptual. Revista Chilena de Psiquiatría y Neurología de la Infancia y adolescencia, 27(1), 61–71.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 user’s guide (p. 635). Amos Development Corporation.

Arthaud-day, M. L., Rode, J. C., Mooney, C. H., & Near, J. P. (2005). The subjective well-being construct: A test of its convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity. Social Indicators Research, 74(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8209-6

Asamblea General de Naciones Unidas. (2015). Transformar Nuestro Mundo: la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible. Resolución aprobada por la Asamblea General el 25 de septiembre de 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from http://www.chileagenda2030.gob.cl/storage/docs/Transformar_nuestro_mundo_La_agenda_2030_para_el_Desarrollo_Sostenible.pdf.

Bedin, L. M., & Sarriera, J. C. (2014). Propriedades psicométricas das escalas de bem-estar: PWI, SWLS, BMSLSS e CAS. Psychometric Properties of the Well-Being Scales: PWI, SWLS, BMSLSS and CAS., 13(2), 213–225.

Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J. E. (2014). Multifaceted concept of child well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, J.E. Korbin, (Eds.), Handbook of child wellbeing: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp. 1–27). Springer.

Bilbao, M., Torres-Vallejos, J., & Juarros-Basterretxea, J. (2020). Bienestar subjetivo en niños, niñas y adolescentes del Sistema de Protección de Infancia y Justicia Juvenil en Chile. Inclusão Social, 13(2).

Bradshaw, J., Crous, G., & Turner, N. (2017). Comparing children’s experiences of schools-based bullying across countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2017.06.060

Bradshaw, J., Keung, A., Rees, G., & Goswami, H. (2011). Children’s subjective well-being: International comparative perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(4), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.05.010

Bradshaw, J., & Richardson, D. (2009). An index of child well-being in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 319–351.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1987). La ecología del desarrollo humano. Paidós.

Bruck, S., & Ben-Arieh, A. (2020). La historia del estudio Children’s Worlds. Sociedad e Infancias, 4, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.5209/soci.68411

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cabieses, B., Obach, A., & Molina, X. (2020). La oportunidad de incorporar el bienestar subjetivo en la protección de la infancia y adolescencia en Chile. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 91(2), 183. https://doi.org/10.32641/rchped.v91i2.1527.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage.

Carlsson, F., Lampi, E., Li, W., & Martinsson, P. (2014). Subjective well-being among preadolescents and their parents – Evidence of intergenerational transmission of well-being from urban China. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 48, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2013.10.003

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9093-z

Casas, F. (2017). Analysing the comparability of 3 multi-item subjective well-being psychometric scales among 15 countries using samples of 10 and 12-year-olds. Child Indicators Research, 10(2), 297–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9360-0

Casas, F., Alfaro, J., Sarriera, J. C., Bedin, L., Grigoras, B., Bălţătescu, S., Malo, S., & Sirlopú, D. (2015a). El bienestar subjetivo en la infancia: Estudio de la comparabilidad de 3 escalas psicométricas en 4 países de habla latina. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 14(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol14-Issue1-fulltext-522

Casas, F., Bello, A., González, M., & Aligué, M. (2013). Children’s subjective well-being measured using a composite index: What impacts Spanish first-year secondary education students’ subjective well-being? Child Indicators Research, 6(3), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2019). Subjective Well-Being Decreasing With Age: New Research on Children Over 8. Chid Development, 90(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13133.

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2020). The evolution of positive and negative affect in a longitudinal sample of children and adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1503–1521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09703-w

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2021). Analysing comparability of four multi-item well-being psychometric scales among 35 countries using Children’s worlds 3rd wave 10 and 12-year-olds samples. Child Indicators Research, online first. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09825-0

Casas, F., González, M., & Navarro, D. (2014). Social psychology and child well-being. In F. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frones, & J. Korbin, handbook oh child well-being. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Casas, F., & Rees, G. (2015). Measures of Children’s subjective well-being: Analysis of the potential for cross-National Comparisons. Child Indicators Research, 8(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9293-z

Casas, F., Sarriera, J. C., Alfaro, J., González, M., Bedin, L., Abs, D., Figuer, C., & Valdenegro, B. (2015b). Reconsidering life domains that contribute to subjective well-being among adolescents with data from three countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9520-9

Centro Iberoamericano de Derechos del Niño, CIDENI. (2019). Derechos en acción: ¿Cómo ha cambiado la Infancia en Chile en 25 años?. Santiago. http://www.cideni.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/01_DerechosEnAccion-Cideni-3.pdf

Centro de Investigación en Complejidad Social & Centro de Estudios en Bienestar y Convivencia Social (2021). Informe Descriptivo Proyecto de investigación: Estudio Internacional Sobre Bienestar Infantil. Proyecto ISCWeB 2017–2019. Concurso Interfacultades UDD Año 2018. Dirección de Investigación y Doctorados. Universidad del Desarrollo.

Centro de Políticas Públicas UC. (2017). Protección a la Infancia Vulnerada en Chile: La Gran Deuda Pendiente. Temas de la Agenda Pública, 12(101). https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Paper-N%C2%BA-101-Protecci%C3%B3n-a-la-infancia-vulnerada-en-Chile.pdf

Céspedes Carreño, C., Viñas i Poch, F., Malo Cerrato, S., Rubio Rivera, A., & Oyanedel Sepúlveda, J. C. (2019). Comparación y relación del bienestar subjetivo y satisfacción global con la vida de adolescentes autóctonos e inmigrantes de la Región Metropolitana de Chile. RIEM: Revista Internacional de Estudios Migratorios, 9(2), 257–281.

Chaverri Chaves, P. C., & Arguedas Ramírez, A. A. (2020). Políticas Públicas Basadas en Evidencia: una revisión del concepto y sus características. Revista ABRA, 40(60), 49–76.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Cho, E. Y.-N. (2018). Links between poverty and Children’s subjective wellbeing: Examining the mediating and moderating role of relationships. Child Indicators Research, 11(2), 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9453-z

Chui, W. H., & Wong, M. Y. H. (2016). Gender differences in happiness and life satisfaction among adolescents in Hong Kong: Relationships and self-concept. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 1035–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0867-z

CONICYT/FONDECYT. (2008). Bioética en Investigación en Ciencias Sociales. Ministerio de Educación-Chile. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from http://repositorio.conicyt.cl/bitstream/handle/10533/206683/BIOETICA_EN_INVESTIGACION_EN_CIENCIAS_SOCIALES.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Contreras, J. I., Contreras, L., & Rojas, V. (2015). Análisis de programas relacionados con la intervención en niños, niñas y adolescentes vulnerados en sus derechos: La realidad chilena. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 14(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol14-Issue1-fulltext-528

Cummins, R. A. (2014). Understanding the well-being of children and adolescents through homeostatic theory. Handbook of child well-being, 635–661.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Dinisman, T., & Ben-Arieh, A. (2016). The characteristics of Children’s subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0921-x

Dinisman, T., Zeira, A., Sulimani-Aidan, Y., & Benbenishty, R. (2013). The subjective well-being of young people aging out of care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1705–1711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.07.011

Farías Olavarría, F., Orellana Fonseca, C., & Pérez, C. (2015). Perfil de las Publicaciones sobre Bienestar Subjetivo en Chile. Cinta de Moebio, 54, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-554X2015000300002

Feldman Barrett, L., & Russell, J. A. (1998). Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 967–984. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.967

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858

González-Carrasco, M., Vaqué, C., Malo, S., Crous, G., Casas, F., & Figuer, C. (2019). A qualitative longitudinal study on the well-being of children and adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9534-7

Gross-Manos, D. (2017). Material well-being and social exclusion association with children’s subjective well-being: Cross-national analysis of 14 countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.048

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034391123010

Huebner, E. S., Seligson, J. L., Valois, R. F., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). A review of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 79(3), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5395-9

International Wellbeing Group. (2013). Personal wellbeing index – Adult - manual, 5th version: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from http://www.acqol.com.au/iwbg/wellbeing-index/index.php.

Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas, JUNAEB. (2020). Indicadores de vulnerabilidad. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://junaebabierta.junaeb.cl/catalogo-de-datos/indicadores-de-vulnerabilidad/.

Kaye-Tzadok, A., Kim, S. S., & Main, G. (2017). Children’s subjective well-being in relation to gender — What can we learn from dissatisfied children? Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.058

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

Knies, G. (2011). Life satisfaction and material well-being of young people in the UK. In: Understanding Society: Early Findings from the First Wave of the UK’s Household Longitudinal Study. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/research/findings/early.

Lawler, M. J., Newland, L. A., Giger, J. T., Roh, S., & Brockevelt, B. L. (2017). Ecological, relationship-based model of Children’s subjective well-being: Perspectives of 10-year-old children in the United States and 10 other countries. Child Indicators Research, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9376-0

Llosada Gistau, J., Casas Aznar, F., & Montserrat Boada, C. (2020). The subjective well-being of children in kinship care. Psicothema. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from http://www.psicothema.com/pdf/4527.pdf.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.616.

Ma, C. Q., & Huebner, E. S. (2008). Attachment relationships and adolescents’ life satisfaction: Some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychology in the Schools, 45(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20288

Main, G. (2019). Money matters: A nuanced approach to understanding the relationship between household income and child subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1125–1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9574-z

Metler, S. J., & Busseri, M. A. (2017). Further evaluation of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Evidence from longitudinal and experimental studies. Journal of Personality, 85(2), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12233

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (2020). Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes. Síntesis de resultados CASEN, 2017. Observatorio Social. Retrieved April 16, 2021 from http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/storage/docs/casen/2017/Resultados_nna_casen_2017.pdf.

Mullender, A., Hague, G., Imam, U., Kelly, L., Malos, E., & Regan, L. (2002). Children's perspectives on domestic violence. SAGE Publications.

Navarro, D., Montserrat, C., Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F., & Crous, G. (2017). Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child and Family Social Work, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12215

Oliveros Werner, C. (2015). Medición del bienestar subjetivo y cumplimiento de participación infantil en Chile. Revista de Psicología UVM. Retrieved April 16, 2021 from https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12536/579.

Oyanedel, J. C., Alfaro, J. & Mella, C. (2015). Bienestar Subjetivo y Calidad de Vida en la Infancia en Chile. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 13(1), 313–327.

Oyanedel, J. C., Alfaro, J., Varela, J., & Torres, J. (2014). ¿ Qué afecta el bienestar subjetivo y la calidad de vida de las niñas y niños chilenos? Resultados de la Encuesta Internacional sobre Bienestar Subjetivo Infantil. LOM.

Oyarzún Gómez, D. M. V. (2016). Predictores del bienestar subjetivo de niños, niñas y adolescentes en Chile. TDX (Tesis Doctorals En Xarxa). Retrieved April 15, 2021 from http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/669315.

Oyarzún, D., Casas, F., & Alfaro, J. (2019). Family, school, and Neighbourhood microsystems influence on children’s life satisfaction in Chile. Child Indicators Research, 12(6), 1915–1933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9617-5

Rees, G. (2018). Children’s leisure activities and subjective well-being: A comparative analysis of 16. In L. Rodriguez de la Vega & W. N. Toscano (Eds.), Handbook of leisure, physical activity, sports, recreation and quality of life (pp. 31–49). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75529-8_3

Rees, G. (2021). Comparación del bienestar subjetivo de los niños en todo el mundo. Sociedad e Infancias, 5, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.5209/soci.72096

Rees, G., Pople, L., & Goswami, H. (2011). Understanding children’s wellbeing: Links between family economic factors and children’s subjective well-being: Initial findings from wave 2 and wave 3 surveys. The Children’s Society.

Reyes Reyes, F., Alfaro Inzunza, J., Varela Torres, J., & Guzmán Piña, J. (2019). Diferencias en el bienestar subjetivo de adolescentes chilenos según género en el contexto internacional. Journal De Ciencias Sociales, (13). https://doi.org/10.18682/jcs.vi13.894.

Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.145

Sarriera, J. C., Casas, F., Bedin, L., Abs, D., Strelhow, M. R., Gross-manos, D., & Giger, J. (2015). Material resources and Children’s subjective well-being in eight countries. Child Indicators Research, 8(1), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9284-0

Sarriera, J. C., Saforcada, E., Tonon, G., de La Vega, L. R., Mozobancyk, S., & Bedin, L. M. (2012). Bienestar Subjetivo de los Adolescentes: Un Estudio Comparativo entre Argentina y Brasil. Psychosocial Intervention, 21(3), 273–280. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/inter/v21n3/04.pdf.

Saunders, P., & Brown, J. E. (2020). Child poverty, deprivation and well-being: Evidence for Australia. Child Indicators Research, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09643-5

Seligson, J.L., Huebner, E.S, Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale (BMSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 61, 121–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021326822957.

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2005). An investigation of a brief life satisfaction scale with elementary school children. Social Indicators Research, 73(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-2011-3

Shek, D. T. L., & Li, X. (2016). Perceived school performance, life satisfaction, and hopelessness: A 4-year longitudinal study of adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 921–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0904-y

Strelhow, M. R. W., Sarriera, J. C., & Casas, F. (2020). Evaluation of well-being in adolescence: Proposal of an integrative model with hedonic and eudemonic aspects. Child Indicators Research, 13(4), 1439–1452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09708-5

Tesch-Römer, C., Motel-Klingebiel, A., & Tomasik, M. J. (2007). Gender differences in subjective well-being: Comparing societies with respect to gender equality. Social Indicators Research, 85(2), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9133-3.

UNICEF. (2018). Agenda de Infancia 2018–2021. Desafíos En Un Área Clave Para El País, Unicef Chile, Santiago de Chile. Retrieved April 15, 2021 fromhttps://www.unicef.org/chile/media/1911/file/agencia_infancia_2018-2021.pdf

Uyan-Semerci, P., Erdoğan, E., Akkan, B., Müderrisoğlu, S., & Karatay, A. (2017). Contextualizing subjective well-being of children in different domains: Does higher safety provide higher subjective well-being for child citizens? Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.050.

Žukauskienė, R. (2014). Adolescence and Well-Being. In Handbook of Child Well-Being (pp. 1713–1738). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_67.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Directorate of Academic Development and the Faculty of Psychology of the Universidad del Desarrollo for financial support for research that is part of the Doctoral Program for Psychology, Health and Quality of Life of the Universitat de Girona.

Funding

This article is part of a doctoral thesis, which received partial financial support from the Universidad del Desarrollo. The University supported the information gathering process for the thesis. Some of that information is included in this article. The University had no participation in the design of the study, data analysis or results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Loreto Ditzel, Ferran Casas; Methodology: Javier Torres, Ferran Casas, Loreto Ditzel; Formal analysis and investigation: Loreto Ditzel, Javier Torres; Writing - original draft preparation: Loreto Ditzel; Writing – review and editing: Javier Torres, Ferran Casas, Alejandra Villarroel; Funding acquisition: Loreto Ditzel; Supervision: Ferran Casas.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Aspects

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out by the Universidad de Girona in the Doctoral Program in Psychology, Health and Quality of Life for research on people as well as the protocols for ethical research that guides scientific studies in Chile (CONICYT/FONDECYT, 2008).

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ditzel, L., Casas, F., Torres-Vallejos, J. et al. The Subjective Well-Being of Chilean Children Living in Conditions of High Social Vulnerability. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 1639–1660 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09979-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09979-7