Abstract

To date, most cross-country comparisons of children’s subjective well-being have been conducted using single-item scales. Despite multi-item scales being more powerful for this purpose, they have seldom been tested on children when comparing results among more than 4 countries. Moreover, with very few exceptions, international comparisons have mostly been carried out using samples of children aged 12 or over and it is therefore uncertain how the scales available might work among younger populations, even if some scales have been tested in a few countries. We tested 3 psychometric scales on a sample of over 34,000 children from 15 countries aged mostly 10 and 12: the SLSS, the BMSLSS and the PWI-SC. We used the pooled database to identify models with a good fit by means of Confirmatory Factor Analysis, providing construct validity for each of the three scales for this set of countries. The comparability of the scales among countries was tested using Multi-group Confirmatory Factor Analysis to assess to what extent it is valid to make cross-national comparisons. Our results suggest that it is acceptable to compare correlations and regressions between most of the countries in our survey using each of these measures, with only a few exceptions. Some of the models using the specific modified SLSS version adopted in this research displayed promising results due to the fact that their correlations and regressions appeared to be comparable among all countries in the sample. However, mean scores for the overall indexes are only comparable among countries in some cases using partial intercept constraints. Two Multi-group Structural Equation Models including the three correlated multi-item psychometric scales plus two single-item scales (Overall Life Satisfaction and Overall Happiness Scale) displayed good fit indexes with constrained loadings for all countries, both for the 10 and 12-year-old samples. This result suggests that subjective well-being comparability increases among countries when using the five psychometric scales all together. With semi-partial constrained loadings and intercepts, fit statistics suggest that the means of this overall model can cautiously be compared among all countries: comparable items and not strictly comparable items were identified. Correlations among the psychometric scales and regressions of the multiple-item scales on the single-item scales clearly show different patterns among countries and variations according to age group, suggesting a high diversity of interrelations among these measures depending on age and different language and socio-cultural contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

In the psychometric tradition, it is well-established that multi-item scales are more robust than single item scales for measuring any non-directly observable construct (Furr 2010; Diamantopoulos et al. 2012). This basic principle seems to be ignored by international agencies, which often compare countries and construct lead tables based only on single-item scales. Children’s subjective well-being (SWB) has mostly been assessed in international comparisons using the Cantril ladder test - a well-known single-item scale - with data taken from the HBSC survey (see Adamson 2007).

In the scientific literature, the cross-country comparability of multi-item SWB scales has in some cases been analysed using samples of adolescents aged 12 or above. In general, such analysis has been limited to 2, 3 or 4 countries, with a few exceptions, such as Casas and Rees (2015). For example, Casas et al. (2012) analysed the performance of several single-item and three multi-item measures (PWI, SWLS and BMSLSS) in four Romance-language speaking countries. In relation to the multi-item measures, by means of structural equation modelling they found support for factor invariance across the four countries, meaning that the measures could be used to compare country differences at least in terms of correlations and regression coefficients. This study also highlighted some of the complexities and challenges involved in translating and representing the same psychometric well-being measures in different languages. English words such as ‘happiness’ and ‘satisfaction’ cannot necessarily be directly and precisely translated, and the same goes for some of the concepts covered in the scales – for example ‘community’; the opposite situation is illustrated in Casas et al. (2013b), which use an item in Spanish and Arabic on satisfaction with love life that cannot be precisely translated into English. In this last quoted study, the authors also found support for comparisons of correlations and regressions between samples, but not mean scores, when analysing adolescents’ data from Spain and Algeria. They suggested that the differences in mean scores between countries may be partly attributable to different response styles, which in turn may be related to differences in culture and socialisation. The authors concluded that caution is required in making simple cross-national comparisons of mean scores for subjective well-being measures.

There is a lack of large-scale data sets containing children’s subjective well-being scores for large ranges of countries and related to this there is a limited body of work on the subjective well-being of children under 12 years of age.

The ISCWeB international project database offers a unique opportunity to test the comparability of some subjective well-being psychometric scales because items from it have been included in questionnaires for 8, 10 and 12-year-old children already administered in 15 countries. This project consists of a cross-national survey of children’s subjective well-being and daily activities developed by an international group of researchers linked to the International Society of Child Indicators. The overall aims of the ISCWeB project are to collect solid and representative data on children’s lives and daily activities, their use of time and, in particular, their own perceptions and evaluations of their well-being in order to improve said well-being by influencing opinion leaders, decision makers, professionals and the general public, both in the project countries and internationally.

1.2 Aims

The aim of this article is to contribute to this ongoing debate regarding the potential comparability of some of the children’s subjective well-being multi-item psychometric scales across nations, cultures and languages by determining the extent to which each of the analysed scales and its items are comparable.

We have chosen Multi-group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MCFA) by means of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) as one of the ways of analysing the comparability of psychometric scales across countries, cultures or languages. SEM is a multivariate technique that seeks to explain the relationship between multiple variables (even unobservable or “latent” variables), including the measurement errors in the model. It takes advantage of psychometric and econometric knowledge, and it is founded in factor analysis and multiple regression analysis (Hair et al. 2014). CFA is used to assess the construct validity of a measurement model (e.g., a psychometric scale). When using the same model with different groups (e.g., samples from different countries) we need to examine the degree to which the models are equivalent across groups (i.e., their comparability) (Comşa 2010).

2 Data

The data set used here is taken from the second wave of the International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB: www.isciweb.org). The ISCWeB data were collected by means of group-administered questionnaires within the school context. Three different versions of the questionnaires were used for the three age groups (8, 10 and 12), each questionnaire including more items the older the group (Rees and Main 2015). An international committee supervised data collection design in order to guarantee appropriate representativity of the data from each region or country. More details on the data collection procedure in each country can be obtained in www.isciweb.org.

In this study, only data from five psychometric scales included in the questionnaire from the 10 and 12-year-old groups are used, because identical 0 to 10 scales were used for all psychometric scales, while a five-point emoticon scale was used in the 8-year-old questionnaires, requiring a separate further analysis.

2.1 Data Sets

In each country, approval was obtained from the relevant ethics committee prior to the survey being conducted. The children were informed that their answers would be treated anonymously, that any information given would be considered confidential, that their participation was voluntary and that they could stop answering the questionnaire at any time.

Paper questionnaires were used in 13 countries, while in the United Kingdom (England) and in most cases in Spain (Catalonia) the survey was administered online.

The original questionnaire was written in English. In countries other than the United Kingdom the questionnaires were translated into other languages as required. The translation process involved an initial translation from English, a translation of the resulting questionnaire back into English and then a resolution of any resulting anomalies in wording between the original version and the back-translated version. This resolution included taking into account discussions with children where possible and the knowledge of the local research teams. Additionally, an effort was made to ensure that the visual presentation of the questionnaire and labelling of responses (e.g., anchoring points for scales) was consistent in all countries, as variations in these aspects may result in variations in response patterns (Rees and Main 2015). Advice from children was required in some of the participating countries in order to improve the format used to present the scales and the format they recommended was the one used in the questionnaires for all countries in this project (Casas et al. 2013a).

2.2 Measures

The ISCWeB questionnaires for both 10 and 12-year-olds include the items on the modified versions of the SLSS, BMSLSS, and PWI-SC multiple-item subjective well-being scales, as well as the two single-item scales on Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS) and Overall Happiness (OHS).

2.2.1 SLSS (Modified Version)

The Student Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) was developed in the US by Huebner (1991). The original scale consists of seven items designed to refer to context-free life satisfaction, and respondents are asked to agree or disagree with them. The initial version used a four-point frequency response scale, but a six-point agree-disagree scale was subsequently recommended by the author. The scale has been shown to have good reliability and validity with general samples of young people in the US (for a summary, see Huebner and Hills 2013) and has also been used in a number of other countries. Because of the well-known optimistic bias effect, particularly important among children, unlike the original version an 11-point scale from ‘Do not agree at all’ to ‘Totally agree’ is used in the Children’s Worlds project in order to make the instrument more sensitive and capture more variance. This option has already been adopted by some authors with similar scales when administered to adolescents (e.g., with Diener et al.’s SWLS, in Casas et al. 2012).

During the piloting of this scale in different countries and with different languages it was decided that only four of the original items would be used – i.e., not including any of the reversed items – (see the wordings of the first four items in Table 3), and that one more item would be added (‘the things in my life are excellent’) adapted from the SWLS (Diener et al. 1985), in order to improve the scale’s reliability.

2.2.2 BMSLSS (Modified Version)

Seligson et al. (2003) developed the Brief Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS), which contains single-item measures of five key domains in children’s lives – family, friends, school, self and living environment. The scale has subsequently been tested and validated in the US with children and young people aged 8 to 18 (Huebner et al. 2006, ) as well as in some other countries. Response options for the original version were based on a seven-point scale from ‘Terrible’ to ‘Delighted’, originally proposed by Andrews and Withey (1976). Unlike the original version, an 11-point scale from ‘Not at all satisfied’ to ‘Totally satisfied’ was used on the 10 and 12 year-olds in the Children’s Worlds project.

During the piloting of this scale in different countries it was decided that slightly different wordings would be used to assess the same five domains of the original scale so as to increase understanding and comparability among different languages. The items used were satisfaction with: ‘Your family life’, ‘Your friends’, ‘Your school experience’, ‘Your own body’ and ‘The area you live in, in general’.

2.2.3 PWI-SC (Two Modified Versions)

Cummins and Lau (2005) developed a children’s version of the adults’ PWI: the Personal Well-Being Index – School Children (PWI-SC). Both versions of the PWI consist of seven items, with a response scale from zero to ten. The PWI-SC was validated in Australia (Tomyn and Cummins 2011). The original scale used an 11-point bipolar scale. However, the latest manual of the PWI recommends using unipolar scales and therefore labels ranging from ‘Not at all satisfied’ to ‘Totally satisfied’ were included.

During the piloting of this scale in different countries it was decided that slightly different wordings be used to assess the fourth domain of the original scale so as to increase understanding and comparability among different languages. The items used here were satisfaction with: ‘All the things you have’, ‘Your health’, ‘The things you want to be good at’, ‘Your relationships with people in general’, ‘How safe you feel’, ‘Doing things away from home’ and ‘What may happen to you later in your life’.

2.2.4 Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS)

The importance of including a single-item scale on overall life satisfaction when studying subjective well-being was first highlighted by Campbell et al. (1976). In our research we have included a question on ‘Satisfaction with your life as a whole’, using a 0–10 scale, from ‘Not at all satisfied’ to ‘Totally satisfied’.

This item will be used to check for the convergent validity of the psychometric scales in each different language and cultural context. According to Cummins et al. (2003), this item represents the most abstract and least deconstructed level of life satisfaction and any other deconstructed instrument should therefore display a high contribution when regressed on the OLS. It is important to acknowledge that taking this approach implies an underlying assumption that people’s ratings of domain satisfaction contribute to their rating of overall life satisfaction – that is, at least to some extent, survey respondents use their assessments of how they feel about different aspects of their lives to come to a conclusion about their assessment of their life as a whole (Casas and Rees 2015).

2.2.5 Overall Happiness Scale (OHS)

The importance of including a single-item scale on overall happiness when studying subjective well-being was also pointed out by Campbell et al. (1976). In our research we have included a question asking ‘Overall, how happy have you been feeling during the last 2 weeks?’ using a 0–10 scale, from ‘Not at all happy’ to ‘Totally happy’.

3 Procedure

3.1 Data Preparation

The data set used for this analysis had been cleaned and prepared as part of the international project. This process included identifying and excluding cases with high proportions of missing data, and identifying and excluding cases with systematic response patterns. The latter point is particularly relevant to the topic of this article because, for example, Cummins and Lau (2005) recommend that respondents who score at the top or bottom of the scale for all items on the PWI-SC should be excluded from analysis due to constant extreme answers tending not to be reliable. There are problems with this approach, however, in that it automatically excludes anyone who expresses complete satisfaction with all aspects of their life covered by one instrument – and many children at these ages seem to be extremely satisfied with their lives, although that does not mean they are satisfied with all aspects or dimensions in their life measured by other instruments. With the current data set it was possible to take a broader approach because the questionnaire included a number of different sets of items. Thus, the approach taken was that of identifying uniform response patterns for five different sets of items in the data set and excluding cases if they exhibited such patterns for more than one of the five item sets. Cases excluded on this basis are therefore not included in the sample used in this paper (Rees and Main 2015).

In addition, basic checks were carried out on the extent of missing data for each variable included in the analysis. It was decided to exclude from the analysis any variable with more than 5 % of values missing (Rees and Main 2015). The remaining missing values for satisfaction items were then substituted by regression, as implemented in SPSS version 19.

3.2 Sample

A representative sample for the entire country was obtained in Estonia, Ethiopia, Israel, Nepal, Norway, Romania and South Korea, while a representative regional sample was obtained in Algeria (El Bayedh, Tlemcen and Oran), Colombia (Antioquia), Germany (Thuringia, Hesse, Baden-Wurttemberg and North Rhine-Westphalia), Poland (Wielkopolska), South Africa (Western Cape), Spain (Catalonia), and Turkey (Istanbul), and representative data from England were collected as a part of the United Kingdom.

After data depuration, the final sample was N = 17,148 children for the 10-year-old group and N = 17,463 children for the 12-year-old group. Taking into account that N = 66 cases were deleted because of missing gender values among the 10-year-olds and N = 25 among the 12-year-olds, the distribution of the final sample according to country, gender and age group is that reflected in Table 1.

As data collection was based on class-groups at school, the mean age of each age group was slightly above the selected age, although not all children display exactly the same age distribution in all of the countries, as may be expected. The precise age distribution at the time of data collection is displayed in Table 2.

3.3 Data Analysis

In order to first assess the validity of the factorial structure of multi-item scales, we tested different CFA models for each of the measures. AMOS 19 software with maximum likelihood estimation was used to this end. Because subjective well-being data usually differ greatly from statistical normality, data were handled in Structural Equation Models by means of the bootstrap method to compute standard errors.

The fit indices considered were the CFI (Comparative Fix Index), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). We assumed that results higher than .950 for the CFI and results below .05 for the RMSEA and SRMR are excellent, in accordance with Arbuckle (2010) and Byrne (2010). According to some other authors, RMSEA values up to .08 represent acceptable errors of approximation in larger samples (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Byrne 2010; Marsh et al. 2010), while CFI values greater than .90 reflect acceptable fit to the data (Marsh et al. 2010).

In order to meaningfully compare statistics across groups, measurement invariance is required. Three steps are necessary to check for this: (a) configural invariance (unconstrained variables); (b) metric invariance (constrained factor loadings); (c) scalar invariance (constrained factor loadings and intercepts). Metric invariance allows meaningful comparison of correlations and regressions. Scalar invariance allows meaningful comparison of the latent means (Coenders et al. 2005). Therefore, we will test each multi-group model in three steps. When any constraint is added to a model, a change in the CFI of more than .01 is considered unacceptable (Chen 2007; Cheung and Rensvold 2002).

The analytical procedure for each of the four measures being tested was as follows. First, a CFA was conducted for each measure using the pooled sample to test the model fit and identify any problematic items. Once any modifications had been made to the initial model (exclusion of items and/or inclusion of error covariance constraints), a multi-group CFA was conducted to test measurement invariance across countries.

The final step was to test an overall Structural Equation Model including the correlated three multi-item psychometric scales (the 7-item version in the case of the PWI-SC) and the two single-item scales (OLS and OHS), in order to explore the relationships among the different psychometric scales in each of the 15 countries and with the pooled sample. We analyse the Squared Multiple Correlations (SMC) obtained with this model with constrained loadings because they indicate how accurately each variable is predicted by the other variables in the model (Arbuckle 2010; Byrne 2010). Additionally, the remaining % variance is accounted for by its unique factor error. If error represented measurement error only, we could say that the estimated reliability of the variable is the value displayed for each variable SMC. Therefore, each SMC value is an estimate from the lower band of reliability relating to its variable (Arbuckle 2010; Byrne 2010).

4 Results

Descriptive statistics for the measures used in the analysis are shown in Table 3.

4.1 SLSS

4.1.1 10-Year-Olds

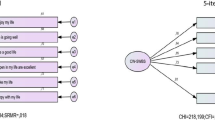

This scale fits well enough for the 10-year-olds’ responses to the 5 original items used in this project when including two error covariances in the model (Fig. 1; Model 2 in Table 4). The multi-group model with 15 countries fits very well, even with constrained loadings (Models 3 and 4 in Table 4). Therefore, correlations and regressions of this model are comparable among the 15 countries in our database.

The multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts does not fit because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 (Model 5 in Table 4). However, a semi-partial constrained model with good fit is observed when item 2 intercept is unconstrained (Model 6 in Table 4). The mean scores for item 2 are therefore not strictly comparable cross-culturally, whereas those of all other items are. In this situation, it is recommended that the mean scores for the overall scale be compared cautiously among countries.

4.1.2 12-Year-Olds

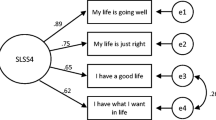

This scale does not fit for the 12-year-old pooled database of the 15 countries and the 5 original items used in this project (Model 7 in Table 4). When item 4 is deleted, it fits well enough with no error covariance (Fig. 1; Model 8 in Table 4) – we will call this version the SLSS4.

The multi-group model of the SLSS4 with 15 countries fits very well, even with constrained loadings (Models 9 and 10 in Table 4). Therefore, correlations and regressions are comparable among countries.

The multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts does not fit because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 (Model 11 in Table 4). However, it fits very well when only items 1 and 3 have constrained intercepts (Model 12 in Table 4). The means for items 2 and 4 are therefore not strictly cross-country comparable, whereas those of items 1 and 3 are. In this situation, it is recommended that the mean scores for the overall scale be compared cautiously among countries.

4.2 BMSLSS

4.2.1 10-Year-Olds

This scale fits well enough for the 10-year-old pooled database and the 5 original items used in this project with no error covariance (Fig. 2; Model 1 in Table 5). The multi-group model with 15 countries fits very well (Model 2 in Table 5).

The multi-group model with constrained loadings only fits when 4 countries are excluded: Algeria, Colombia, Germany and Turkey (Model 5 in Table 5). Therefore, correlations and regressions are comparable among countries only when the aforementioned countries are excluded.

The multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts does not fit because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 (Model 6 in Table 5). However, it fits very well when only items 1 and 2 have constrained intercepts (Model 7 in Table 5). The mean scores for items 3, 4 and 5 are therefore not strictly cross-country comparable, whereas those of items 1 and 2 are. In this situation, it is recommended that the mean scores for the overall scale be compared cautiously only among the countries included in Model 5.

4.2.2 12-Year-Olds

This scale fits well enough with the 12-year-old sample and the 5 original items used in this project (Model 8 in Table 5). However, with one error covariance its fit is excellent (Fig. 2; Model 9 in Table 5). The multi-group model with 15 countries fits very well (Model 10 in Table 5).

The multi-group model only fits with constrained loadings when 4 countries are excluded: Algeria, Ethiopia, Germany and Romania (Model 14 in Table 5). Therefore, correlations and regressions are comparable among countries only when the aforementioned countries are excluded.

Definitively, the mean scores for this scale do not appear to be comparable among countries in any of the cases. No model with constrained loadings and intercepts fits, even when excluding the aforementioned countries and testing different semi-partial constraints, because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 in all cases. The domains included in this scale appear to be understood differently and answered by means of different response styles by 12-year-old children from different countries, languages or cultural contexts. However, we also believe the commonly used fit requirements to perhaps be too strict for the number of countries we are comparing.

4.3 PWI-SC

4.3.1 10-Year-Olds

This scale fits moderately well with the 7 original items used in this project (Model 1 in Table 6). However, with 2 error covariances it fits very well (Fig. 3; Model 2 in Table 6).

The unconstrained multi-group model with 15 countries fits very well (Model 3 in Table 6). With constrained loadings it only fits when 4 countries are excluded: Colombia, Nepal, Poland and Romania (Model 5 in Table 6). Therefore, correlations and regressions are comparable among countries only when the aforementioned countries are excluded.

The multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts does not fit even when excluding these four countries, because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 (Model 7 in Table 6). However, it fits very well when only items 2 and 4 have constrained intercepts (Model 8 in Table 6). The mean scores for items 1, 3, 6 and 7 are therefore not strictly cross-country comparable, whereas those of items 2 and 4 are. In this situation, it is recommended that the mean scores of the overall scale be compared cautiously only among the countries included in Model 6.

4.3.2 12-Year-Olds

This scale fits moderately well with the 12-year-old sample and the 7 original items used in this project (Model 9 in Table 6). However, with 3 error covariances it fits very well (Fig. 3; Model 10 in Table 6).

The unconstrained multi-group model with 15 countries fits very well (Model 11 in Table 6). With constrained loadings it only fits when 4 countries are excluded: Algeria, Colombia, Nepal and Romania (Model 15 in Table 6). Therefore correlations and regressions are comparable among countries only when the aforementioned countries are excluded.

The multi-group model with constrained loadings and intercepts does not fit even when excluding these four countries, because the decrease in CFI is above 0.01 (Model 16 in Table 6). However, it fits very well when only items 4, 5 and 7 have constrained intercepts (Model 17 in Table 6). The mean scores for items 1, 2, 3, and 6 are therefore not strictly cross-country comparable, whereas those of items 4, 5 and 7 are. In this situation, it is recommended that the mean scores of the overall scale be compared cautiously only among the countries included in Model 14.

4.4 Overall SEM Including the Three Correlated Multi-Item Scales Plus the Two Single-Item Scales (OLS and OHS)

Theoretically, different multi-item scales measuring SWB should correlate highly with one another. In previous research, medium to high correlations among the scales used here have been reported in several countries (Casas et al. 2012), as has the fact that they appear to be related to a second order latent variable, suggesting the existence of an SWB supra-construct (Stones and Kozma 1985; Diener et al. 1999; Casas et al. 2012). An SE model including the three multi-item scales used in this study related to a second order latent variable displayed good fit statistics both for the 10-year-old (χ 2 = 2659.92; df = 111; p = .000; CFI = .979; RMSEA = .037 . < 035–.038>; SRMR = .023) and the 12-year-old groups (χ 2 = 2520.09; df = 94; p = .000; CFI = .981; RMSEA = .038 . < 037–.040>; SRMR = .023) with pooled data. We therefore decided to design a more complex overall model to test whether the psychometric scales used to assess subjective well-being have consistent relationships across countries. The multi-group model includes the five measures used in this study: the three multi-item measures correlated with one another and regressed on the two single-item measures (Fig. 4).

4.4.1 10-Year-Olds

Using the pooled sample, the overall SE model displays good fit statistics (Model 1 in Table 7; Fig. 4). Both the unconstrained and constrained loadings multi-group models fit well, suggesting, therefore, that correlations and regressions are comparable among all countries. Because these results do not exclude any country, they also suggest that comparability of the measures improves when using several psychometric scales together. Standardized regression loadings and correlations for each country are displayed in Table 8 (Annex).

The model with constrained loadings and intercepts is not acceptable because the CFI decreases by above .01 (Model 4 in Table 7). When intercepts of several items are unconstrained the model fits well (Model 5 in Table 7): My life is just right (SLSS), Satisfaction with own body, with the area I live in and with my school experience (BMSLSS) and Satisfaction with the things I have, with the things I like to be good at and with doing things away from home (PWI-SC). This means that the intercept for the item on Satisfaction with what may happen to me later in life (PWI-SC) has remained constrained without affecting the fit of the model, as happened when we analysed the scalar invariance of the PWI-SC model alone with the 10-year-old sample. Once again, this result supports increased comparability when using several scales together.

4.4.2 12-Year-Olds

Using the pooled sample, the model displays good fit statistics (Model 6 in Table 7; Fig. 4). Both the unconstrained and constrained loadings multi-group models fit well, suggesting, therefore, that correlations and regressions are comparable among all countries. Because these results do not exclude any country, they also suggest that comparability of the measures improves when using several psychometric scales together. Standardized regression loadings and correlations for each country are displayed in Table 8 (Annex).

The model with constrained loadings and intercepts is not acceptable because the CFI decreases by above .01 (Model 9 in Table 7). When intercepts of several items are unconstrained the model fits well (Model 10 in Table 7): My life is just right, Things in my life are excellent (SLSS), Satisfaction with own body, with the area I live in and with my school experience (BMSLSS) and Satisfaction with the things I have, with health, with the things I like to be good at and with doing things away from home (PWI-SC). This means that the intercept for the items on Satisfaction with my family and Satisfaction with my friends (BMSLSS) have remained constrained without affecting the fit of the model, as happened when we analysed the scalar invariance of the PWI-SC model alone with the 12-year-old sample. Once again, this result supports increased comparability when using several scales together.

A detailed analysis of the results in Table 8 (Annex) reveals a large diversity in relationships among the scales, which differ by country and age group when analysed together in a multi-group SEM.

For the 10-year-old sample:

-

The regression weight of the PWI-SC on the OLS is .535 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .411 in Turkey and .416 in Israel to .682 in Poland and .698 in Spain.

-

The regression weight of the BMSLSS on the OLS is .530 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .434 in Ethiopia and .449 in Romania to .680 in Poland and .687 in Spain.

-

The regression weight of the SLSS on the OLS is .452 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .286 in South Africa and .306 in Colombia to .582 in Poland and .563 in Norway.

-

The regression weight of the PWI-SC on the OHS is .354 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .202 in Spain and .216 in Poland to .432 in Germany and .464 in Israel.

-

The regression weight of the BMSLSS on the OHS is .370 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .203 in Spain and .275 in Poland to .428 in Romania and .437 in Ethiopia.

-

The regression weight of the SLSS on the OHS is .447 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .272 in Poland and .346 in Norway to .524 in Algeria and .570 in Colombia.

-

The correlation between the OLS and the OHS is .481 for the pooled sample and ranges from .274 in Nepal and .287 in Romania to .630 in South Korea and .653 in Norway.

-

The correlation between the BMSLSS and the SLSS is .644 for the pooled sample and ranges from .343 in Spain and .525 in the United Kingdom to .842 in Israel and .951 in Algeria.

-

The correlation between the PWI-SC and the BMSLSS is .953 for the pooled sample and ranges from .836 in South Africa and .854 in Estonia to 1 in Algeria, Nepal, Ethiopia, England and Norway.

-

The correlation between the PWI-SC and the SLSS is .631 for the pooled sample and ranges from .268 in Spain and .437 in Norway to .869 in Nepal and 1 in Algeria.

For the 12-year-old sample:

-

The regression weight of the PWI-SC on the OLS is .528 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .387 in Nepal and .415 in Israel to .576 in Spain and .601 in South Korea.

-

The regression weight of the BMSLSS on the OLS is .549 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .353 in Nepal and .416 in Ethiopia to .621 in United Kingdom and .635 in South Korea.

-

The regression weight of the SLSS4 on the OLS is .462 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .302 in South Africa and .336 in Colombia to .558 in the United Kingdom and .616 in Norway.

-

The regression weight of the PWI-SC on the OHS is .365 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .223 in Colombia and .309 in South Korea and .462 in Norway and .536 in Nepal.

-

The regression weight of the BMSLSS on the OHS is .398 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .297 in Colombia and .303 in South Korea to .458 in Romania and .523 in Ethiopia.

-

The regression weight of the SLSS4 on the OHS is .470 for the pooled sample, and ranges from .335 in Norway and .399 in the United Kingdom to .556 in South Africa and .558 in Romania.

-

The correlation between the OLS and the OHS is .538 for the pooled sample and ranges from .296 in South Africa and .323 in Nepal to .673 in South Korea and .680 in Norway.

-

The correlation between the BMSLSS and the SLSS4 is .637 for the pooled sample and ranges from .485 in South Korea and .501 in Norway to .711 in Colombia and .790 in Nepal.

-

The correlation between the PWI-SC and the BMSLSS is .919 for the pooled sample and ranges from .757 in Algeria to .826 in Israel.

-

The correlation between the PWI-SC and the SLSS4 is .585 for the pooled sample and ranges from .441 in Colombia and .461 in Germany to .622 in Poland and .908 in Nepal.

An analysis of the squared multiple correlations (SMC) (Table 9 in the Annex) for this overall model including the 5 psychometric scales brings us to the following notable conclusions:

-

The degree that each of the 3 latent variables (corresponding to the 3 multi-item psychometric scales) is explained for by each of the single-item psychometric scales displays important variations from country to country. For example, with the 10-year-old sample:

-

63.1 % of the PWI-SC variance in Poland, 62.8 in Spain and 60.3 in South Korea is accounted for by the OLS, while this is true for only 31.8 % in Turkey, 32.4 % in Romania and 33 % in South Africa.

-

67.8 % of the BMSLSS variance in Poland, 65.2 % in Germany and 63.9 % is accounted for by the OLS, while this is true for only 32.8 % in Romania, 34.5 % in Turkey and 34.7 % in Nepal.

-

62.3 % of the SLSS variance in Norway and 61.5 % in South Korea is accounted for by the OLS, while this is true for only 22.3 % in South Africa, 22.9 % in Colombia, 27.2 % in Ethiopia and 27.4 % in Nepal.

-

50.1 % of the PWI-SC variance in Germany, 49.3 % in England and 48.7 % in Norway is accounted for by the OH2W, while this is true for only 19.5 % in Colombia, 24.7 % in Nepal and 27.1 % in Romania.

-

50.7 % of the BMSLSS variance in Germany and 49.3 % in England is accounted for by the OH2W, while this is true for only 21 % in Colombia, 24.4 % in Nepal and 27.7 % in Catalonia.

-

58.5 % of the SLSS variance in South Korea, 57 % in England and 52.4 % in Algeria is accounted for by the OH2W, while this is true for only 23.7 % in Romania, 26.6 % in Ethiopia and 32.9 % in Poland.

-

-

The variance explained by each of the single-item scales, or by the two together, on each of the multiple-item scales tends to increase with the pooled sample between the ages of 10 and 12. However, important variations are observed depending on the country.

-

In general, much more explained variance of the latent variables is accounted for by the OLS than by the OH2W. However, there are a few exceptions. For example, in Algeria and Spain, the SLSS is accounted for in a higher percentage by the OH2W than the OLS.

-

In general, when the OLS and OH2W are considered together, moderate increases are displayed in the percentages of explained variance.

-

Items on the SLSS display a much higher explained variance in relation to their latent variable than those on the PWI-SC or BMSLSS.

-

Item 4 on the SLSS (Have what I want) displays a much lower explained variance in relation to its latent variable than any of the other items, in all countries. In some countries, item 5 also displays a lower squared multiple correlation, as is the case for both age groups with item 2 in Colombia.

5 Discussion

A first important observation comes from analysing Table 3, which displays very high means for all items in the five measures of subjective well-being used in this study, much higher than expected for any adults’ or even older adolescents’ population according to homeostatic theory (Cummins 1998; Cummins and Nitisco 2002; Cummins et al. 2002). These high scores are observed in all 15 countries, and the profile of responses in all countries tends to have the shape of the right half part of a “U”, that is to say, a non-normal distribution. It is for this reason that all of our calculations have been based on the bootstrap ML method.

Results with the pooled sample consistently support the proposition that young children tend to score as being more optimistic, happy and satisfied with their lives than adults or older adolescents and that such high scores tend to decrease with age as part of a natural process (Holte et al. 2013). In our sample, the mean scores for all items in the 12-year-old sample are lower in all cases than those in the 10-year-old sample, the only exception being in Israel; in addition, all standard deviations increase from the ages of 10 to 12 in so far as responses are less concentrated in the extreme scores, with exceptions in only two items (Table 1).

We have identified models with good fit indexes using each of the three different psychometric scales with the pooled database from all countries, supporting the construct validity of each multi-item scale. Therefore, the models presented here can be used for in-country analysis and even cross-group analysis in each country, although specific testing is advisable with each country’s data depending on the type of analysis to be undertaken.

Correlations and regressions of the separate scales appear to be comparable among all but a few countries, as indicated in the previous tables.

The SLSS displays promising results, because it is the only one of the three scales whose correlations and regressions are comparable among all countries in this sample. Additionally, its items display much higher squared multiple correlations, indicating higher explained variance than other items on its respective latent variable. However, not all of its items display comparable mean scores and the explained variance of item 4 is much lower than that of the other items. The non-comparability of the mean scores of some items suggests different response styles, probably due to linguistic and cultural factors.

SLSS mean scores are comparable: (a) for the 10-year-old database, when item 2 is unconstrained, demonstrating that the means of items 1, 3, 4 and 5 are comparable; (b) for the 12-year-old database, when item 4 is not included and items 2 and 5 are unconstrained, demonstrating that only the means of items 1 and 3 are strictly comparable.

The comparability among countries of means for the BMSLSS items is more problematic. In fact, only 2 items on the BMSLSS display comparable means among 11 countries, and only with the 10-y.o. database.

PWI-SC mean scores are comparable among 11 countries: (a) using the 10-year-old database, when items 1, 3, 6, 7 are unconstrained, demonstrating that only the means of items 2, 4 and 5 are strictly comparable; (b) using the 12-year-old database, when items 1, 2, 3, 6 are unconstrained, demonstrating that only the means of items 4, 5 and 7 are comparable.

When testing an overall SE Model including the five psychometric scales used in this study, metric invariance was met, suggesting that correlations and regressions are comparable among all countries when used together (not as separate scales). Additionally, semi-partial scalar invariance was also met when some items did not have their intercepts constrained. In comparison with the scale-by-scale CFA, in the overall SEM the number of comparable items has slightly increased, including two more items from the BMSLSS for the 12-year-old sample and one more item from the PWI-SC for the 10-year-old sample. All of these results suggest that for cross-national, cross-cultural and cross-linguistic comparability it is advisable to use models that include several subjective well-being psychometric scales rather than only one scale. Indirectly, this result also suggests that the overall indexes of the five psychometric scales used here should be tested as potential indicators of the SWB supra-construct.

Table 10 shows a summary of the comparability of all items included in the psychometric scales used here.

The overall SEM has provided us with evidence of an impressive diversity of interrelationships among the five psychometric scales used here, depending on the different cultural and linguistic context. For example, the correlation between the OLS (which refers to a summary of satisfaction with overall life) and OHS (which refers to the feeling of happiness during the last 2 weeks) is extremely low for the two age groups in Nepal, for 10-year-olds in Romania and for 12-year-olds in South Africa (always below .300), while it is very high for the two age groups in South Korea and Norway (above .600). These results suggest that in some countries positive feelings during the last 2 weeks are understood by children of these age groups as being very much related with evaluations on overall life, while in other countries these two ideas are much more weakly related.

The multiple-item scales BMSLSS and PWI-SC (both domain-based subjective well-being scales) display extremely high correlations in several countries, showing multi-collinearity and suggesting they overlap or they may be measuring the same supra-construct. However, when the OLS is taken as the “golden standard” on which to regress other variables, as suggested by homeostasis theory, the regression weights of either of these two scales on the OLS are much lower than expected in some of the countries studied. For example, the two scales display regression weights of below .400 in Nepal with the 12-year-old sample; below .450 on the BMSLSS in Ethiopia for the two age samples and for 10-year-olds in Romania; and below .450 on the PWI-SC in Israel for the two age samples and in Turkey for the 10-year-olds. The regression weights for these two scales on the OHS are in all cases clearly lower than on the OLS.

By contrast, the SLSS (the context-free subjective well-being scale) displays very different correlations with the two domain-based scales depending on the country, from very high with the BMSLSS in Israel and Algeria for the 10-year-olds and in Colombia and Nepal for the 12-year-olds, to low in Spain for the 10-year-olds and medium in South Korea for the 12-year-olds – and from very high for the PWI-SC in Nepal and Algeria for the 10-year-olds and in Nepal and Poland for the 12-year-olds, to very low in Spain and medium in Norway for the 10-year-olds and medium in Colombia and Germany for the 12-year-olds.

Regression weights for the SLSS on the OLS are similar to that on the OHS in many but not all countries. In Poland, the regression weight for the SLSS on the OLS for 10-year-olds is high, while on the OHS it is low; the same pattern is observed for Norway for the 12-year-olds, while the opposite happens for this age group in South Africa.

These results imply that cultural and linguistic contexts - and the specific meaning and understanding of each item in each context - seem to have an important impact not only on response styles, but also on how subjective well-being items and scales relate to one another.

If we compare our results with those published by Casas and Rees (2015), it would seem clear that the fact of using representative samples and representativity having been supervised by an international committee of experts has provided much higher quality data.

In terms of the data sets used here, several limitations should be noted. Firstly, because the survey was school-based in all countries it naturally excludes those children not attending a mainstream school. And secondly, the data are cross-sectional – future research should also focus on collecting longitudinal data.

References

Adamson, P. (Ed.) (2007). Child poverty in perspective: an overview of child well-being in rich countries. Report Card 7. Innocenti Research Centre. UNICEF.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: American’s perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 user’s guide. Chicago: Amos Development Corporation.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of estimating model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rogers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage: Nueva York.

Casas, F., & Rees, G. (2015). Measures of children’s subjective well-being: analysis of the potential for cross-national comparisons. Child Indicators Research, online first.

Casas, F., Sarriera, J. C., Abs, D., Coenders, G., Alfaro, J., Saforcada, E., & Tonon, G. (2012). Subjective indicators of personal well-being among adolescents. Performance and results for different scales in latin-language speaking countries: a contribution to the international debate. Child Indicators Research, 5(1), 1–28. doi:10.1007/s12187-011-9119-1.

Casas, F., González, M., Navarro, D., & Aligué, M. (2013a). Children as advisers of their researchers: assuming a different status for children. Child Indicators Research, 6, 193–212. doi:10.1007/s12187-012-9168-0.

Casas, F., Tiliouine, H., & Figuer, C. (2013b). The subjective well-being of adolescents from two different cultures: applying three versions of the PWI in Algeria and Spain. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0229-z.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Coenders, G., Batista-Foguet, J. M., & Saris, W. (2005). Temas avanzados en modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Madrid: La Muralla.

Comşa, M. (2010). How to compare means of latent variables across countries and waves: testing for invariance measurement. An application using Eastern European societies. Sociológia, 41(6), 639–669.

Cummins, R. A. (1998). The second approximation to an international standard of life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 43, 307–334.

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. L. (2005). Personal wellbeing index – school children. Manual (3rd ed.). Melbourne: School of Psychology, Deakin University.

Cummins, R. A., & Nitisco, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: the role of positive cognitive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 37–69.

Cummins, R. A., Gullone, E., & Lau, A. L. D. (2002). A model for subjective well-being homeostasis: The role of personality. In E. Gullone & R. A. Cummins (Eds.), The universality of subjective well-being indicators. Social indicators research book series. Dordrech: Kluwer.

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., van Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: the Australian unity wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 64(2), 159–190. doi:10.1023/A:1024704320683.

Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Smith, H. L. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Furr, R. M. (2010). Scale construction and psychometrics for social and personality psychology. Los Angeles: Sage.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., & Anderson, R.L. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Harlow (Essex). Pearson Education Ltd (7th ed., Pearson New International Edition).

Holte, A., Berry, M. M., Bekkhus, M., Borge, A. I. H., Bowes, L., Casas, F., et al. (2013). Psychology of child well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frones, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being (pp. 555–631). Dordrecht: Springer.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240. doi:10.1177/0143034391123010.

Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2013). Assessment of subjective well-being in adolescents. In D.H. Saklofske, C.R. Reynolds, & V.L. Schwean (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Child Psychological Assessment. Oxford University Press.

Huebner, E. S., Seligson, J. L., Valois, R. F., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). A review of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 79, 477–484.

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Muthén, B., Asparouhov, T., Morin, A. J. S., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2010). A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment, 22(3), 471–491.

Rees, G., & Main, G. (2015). Children’s views on their lives and well-being in 15 countries: an initial report on the children’s worlds survey, 2013–14. Children’2 Worlds. Retrieved from www.isciweb.org.

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale (BMSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 61(2), 121–145. doi:10.1023/A:1021326822957.

Stones, M. J., & Kozma, A. (1985). Structural relationships among happiness scales: a second order factorial study. Social Indicators Research, 17, 19–28.

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). The subjective wellbeing of high-school students: validating the personal wellbeing index—school children. Social Indicators Research, 101(3), 405–418. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9668-6.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to all principal investigators and to all research team members who have participated in the data collection in the 15 countries included in our sample and to the co-ordinating team of the Children’s Worlds project for kindly allowing us to use their data, to the Jacobs Foundation for supporting the project, and to Barney Griffiths for the English editing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex

Annex

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casas, F. Analysing the Comparability of 3 Multi-Item Subjective Well-Being Psychometric Scales Among 15 Countries Using Samples of 10 and 12-Year-Olds. Child Ind Res 10, 297–330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9360-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9360-0