Abstract

Character strengths are positively valued traits that are expected to contribute to the good life (Peterson and Seligman 2004). Numerous studies have confirmed their robust relationships with subjective or hedonic well-being. Seligman (2011) provided a new framework of well-being suggesting five dimensions that encompass both hedonic and eudemonic aspects of well-being: positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning and accomplishment (forming the acronym PERMA). However, the role of character strengths has not been studied so far in this framework. Also, most studies on the relationships between character strengths and well-being only have only relied on self-reports. This set of two studies examines the relationships of character strengths and the orientations to well-being in two cross-sectional studies (Study 1: N = 5521), while also taking informant-reports into account and utilizing different questionnaires to control for a possible method bias (Study 2: N = 172). Participants completed validated assessments of character strengths and the PERMA dimensions (self-reports in Study 1, self- and informant-reports in Study 2). Results showed that in self-reports, all strengths were positively related to all PERMA dimensions, but there were differences in the size of the relationships. Accomplishment, for example, showed the strongest associations with strengths such as perspective, persistence, and zest, whereas for positive relationships, strengths such as teamwork, love, and kindness were the best predictors. These findings were largely confirmed by informant-reports in Study 2. The findings provide further support for the notion that character contributes to well-being and they could guide the development of strengths-based interventions tailored to individual needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Character strengths are stable traits and represent the positively valued part of personality, in comparison to neutral (such as in the Big Five; John and Srivastava 1999) or negative concepts (such as in maladaptive personality traits; Krueger et al. 2012). By definition, character strengths are expected to contribute to the good life, for oneself and others (Peterson and Seligman 2004). Numerous studies have examined the relationships of character strengths with different indicators of the good life, such as hedonic well-being (Berthold and Ruch 2014; Martínez-Martí and Ruch 2017a; Ruch et al. 2010b; see also Baumann et al. 2019 in this special issue), eudemonic well-being (Goodman et al. 2017), and different orientations to well-being (Buschor et al. 2013; Peterson et al. 2007). However, research in this area has so far neglected two important issues. Firstly, while there are few studies on the associations of character strengths with the presence of well-being (Hausler et al. 2017), no study so far has examined the relationships of strengths with a comprehensive, current model of different orientations to well-being. Secondly, almost all studies so far have relied on self-reports and their results are therefore susceptible to common method bias. We aim at addressing these two issues by examining the associations of character strengths with the orientations to a comprehensive framework of well-being: The orientations to positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (i.e., the PERMA dimensions in Seligman’s 2011 well-being theory) while considering both self- and informant-reports in two studies.

Character Strengths

The study of positive traits (i.e., character) has been largely neglected within personality psychology for a long time: Since Allport’s (1921) suggestion that psychology should be focusing on neutral descriptions of behaviors, only few endeavors were undertaken to create a comprehensive system of positive traits. With the beginning of the new century, interest in the study of character has risen again, and Peterson and Seligman (2004) have provided the currently most influential model of character with their Values-in-Action (VIA) classification of strengths (see Höfer et al. 2019 in this special issue).

The VIA classification encompasses 24 positive traits, so called character strengths. It does not represent a factorial model (such as the Big Five), but a list of traits that were derived from a variety of sources in different fields (including psychology, psychiatry, youth development, and philosophy; see Ruch and Proyer 2015) and that have empirically been shown to contribute to a positive life. Nonetheless, various factorial models based on the VIA-IS, the instrument for the assessment of the 24 character strengths, have been suggested (e.g., McGrath 2014). Based on theoretical assumptions, the character strengths are assigned to six ubiquitous virtues, wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence (see Ruch and Proyer 2015, for an empirical test of this assignment). In order to be included in the classification, a potential strength had to meet most of ten criteria (Peterson and Seligman 2004). The first of these criteria states that “A strength contributes to various fulfillments that constitute the good life, for oneself and for others” (Peterson and Seligman 2004; p. 17). This study will supplement data that tests this first criterion as it is expected that all strengths will be positively related to facets of well-being (used as a proxy for the good life).

Orientations to Well-Being

There are numerous approaches on how a good life or well-being should be conceptualized or measured (see Huta and Waterman 2014). Most current psychological models agree that well-being entails both hedonic (as in happiness, life satisfaction, and the presence of positive and the absence of negative affect) and eudemonic components (indicators of positive psychological functioning, such as having a sense of meaning, or positive relationships to other people). Although current models do not agree on the number, terminology or specific content of the components of well-being, they show a considerable overlap. One of the more recent models comprising both, hedonic and eudemonic aspects, is Seligman’s (2011) well-being theory. He argues that there are five distinct dimensions of well-being that are pursued for their own sake: Positive emotions, engagement (i.e., being often completely focused and losing the track of time, as in flow experiences; cf. Csikszentmihalyi 1990), positive relationships (i.e., having close interpersonal relationships), meaning (i.e., having a sense of purpose in life), and accomplishment (i.e., having ambitions, goals, and experiencing mastery); forming the acronym PERMA.

Butler and Kern (2016) provided an instrument for the assessment of the presence of the PERMA dimensions, and showed that all dimensions strongly relate to other indicators of well-being. Further, there are studies suggesting that also the pursuit of each of the PERMA dimensions is positively related to well-being. Peterson et al. (2005b) developed the Orientations to Happiness questionnaire for the assessment of the components of the predecessor of Seligman’s well-being theory, the authentic happiness theory (Seligman 2002), comprising the orientation to pleasure (i.e., the pursuit of positive emotions), engagement, and meaning. Gander et al. (2017) extended this instrument by adding two scales for the assessment of the orientations to positive relationships and accomplishment. They showed that all orientations to the PERMA dimensions are positively related but still distinguishable and go along with a broad array of indicators of well-being and positive psychological functioning. Further, it has been shown in an intervention study that focusing on each of the PERMA dimensions goes along with an increase in well-being, thus suggesting causal relationships between the pursuit of PERMA and well-being (Gander et al. 2016).

While Seligman (2011) described the five orientations to well-being as components of global well-being, the PERMA framework has also been applied to various settings, such as the education sector (e.g., Norrish et al. 2013) or in the work context (e.g., Slavin et al. 2012). In fact, the three elements of the authentic happiness theory are relevant across a broad range of work-related variables (e.g., Johnston et al. 2013; Martínez-Martí and Ruch 2017b; Proyer et al. 2012).

Character Strengths and Orientations to Well-Being

Previous studies examining the associations between character strengths and the presence of flourishing (using the conceptualization of flourishing suggested by Su et al. 2014, that allows for distinguishing between subjective and psychological well-being, and eighteen facets of well-being) reported strong relationships of character strengths with both, subjective and psychological well-being, with stronger relationships for the latter (Hausler et al. 2017).

Since character strengths are assumed to contribute to fulfillments, they are also expected to contribute to the direct pursuit of well-being. Seligman (2011) suggested that the “twenty-four strengths underpin all five elements” (p. 24) of PERMA. Thus, character should positively relate to the pursuit of all (effective) strategies for attaining well-being. Certain strengths might be predictive of specific strategies, whereas other strengths might be predictive of multiple strategies. Further, strengths have been found to be a valuable starting point for interventions that aim at increasing well-being (e.g., Ghielen et al. 2017; Norrish et al. 2013).

Peterson and colleagues (Peterson et al. 2007) were the first to investigate the links between character strengths and the orientations to happiness (i.e., the pursuit of pleasure/positive emotions, engagement, and meaning) empirically. They found that most character strengths showed positive correlations with all three orientations to happiness. However, there were also differential effects: The numerically highest correlations with the orientation to pleasure were reported for the strengths of hope, zest, and humor. The orientation to engagement showed the numerically highest correlations with zest, curiosity, hope, and persistence. Finally, the orientation to meaning showed the numerically highest correlations with spirituality and gratitude.

Buschor et al. (2013) provide support for these relations by examining the associations of self- and informant-rated character strengths (i.e., ratings by close others) with self-ratings of the orientations to happiness. Whereas they also found positive relations of most self-rated character strengths to all orientations, five strengths contributed to all orientations in informant-ratings: hope, zest, curiosity, love of learning, and creativity. These associations are particularly robust, as they can not be explained by a potential shared method bias. Again, there were also differential effects: Across both self- and informant-ratings, pleasure related strongest to hope, zest, curiosity, humor, and bravery; engagement was mostly related to hope, zest, curiosity, humor, creativity, love of learning, and persistence; while meaning showed the strongest relationships to spirituality, hope, curiosity, gratitude, creativity, leadership, and love of learning.

Thus far, no study has examined the relationships between character strengths with the orientations to all PERMA dimensions to the best of our knowledge. Further, ratings of one’s orientations to well-being by knowledgeable others have never been considered. This analysis will provide a fuller evaluation of the association between strengths and well-being and their overlap. We will also replicate and extend findings on the association between the pursuit of pleasure, engagement and meaning (Buschor et al. 2013; Peterson et al. 2007) with character strengths, and also include the pursuit of positive relationships and accomplishment.

Aims and Overview of Studies

We present two studies that investigate the relationships between character strengths and the orientations to all five dimensions of Seligman’s (2011) well-being theory, which we refer to as orientations to well-being. In Study 1, we examine these relationships through self-ratings, by applying both a variable-centered and a person-centered approach. In Study 2, we extend these findings by also taking informant-ratings of both character strengths and the orientations to well-being into account.

Study 1

Peterson et al. (2005b) suggested studying whether the interaction of the orientations to pleasure, engagement, and meaning relates to well-being beyond the mere effects of each of the dimensions alone. They distinguished between participants low in all three orientations to happiness and characterized them as those with the lowest life satisfaction (“empty life”), while participants high in all three scales were characterized by the highest life satisfaction (“full life”). Taking this idea further, Kavčič and Avsec (2014) presented an analysis based on a person-centered approach. In a cluster analysis they identified four clusters: 1) full life (high scores in all three dimensions), 2) pleasurable life (high scores in pleasure, average scores in engagement, and low scores in meaning), 3) meaningful life (low scores in pleasure, average scores in engagement, and high scores in meaning), and 4) empty life (low scores in all three dimensions). These results could largely be replicated in a sample from seven different countries (Avsec et al. 2016). For most countries, Avsec et al. (2016) reported higher scores in well-being for those with a full life than for those with empty lives, whereas those with pleasurable and meaningful lives were in between, and in most cases not distinguishable from each other with regard to well-being.

In Study 1, we examine the relationships between character strengths and the orientations to the PERMA dimensions in a variable-centered and a person-centered approach. For the former approach, we analyzed the relationships among the dimensions and expected to replicate previous findings; namely, positive associations of character strengths to most orientations to well-being, and particularly strong correlations for specific strengths-orientation relationships (e.g., pleasure with humor, engagement with persistence, and meaning with spirituality). For the orientations to positive relationships, we expected the strongest relationships for those strengths that “involve tending and befriending others” (Peterson and Seligman 2004; p. 29), namely love, social intelligence, and kindness, and teamwork. For the orientation to accomplishment, we expected the strongest relationships for the strengths of persistence, curiosity, love of learning, zest, and hope, and self-regulation – since we expected these strengths to go along with having and pursuing ambitions and goals. For the person-centered approach, we compared the mean levels of strengths of different prototypes of people with regard to the PERMA dimensions (i.e., people showing specific configurations of the PERMA dimensions). This approach was conducted on an exploratory basis.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of N = 5521 (78.4% female) participants. Their mean age was 45.48 years (SD = 12.01), ranging from 18 to 86 years. The majority of the participants (71.9%) indicated living in Germany, 13.8% in Switzerland, 11.1% in Austria, and 2.9% in other countries. Regarding their highest level of education, 0.1% indicated having left school without obtaining a degree, 3.5% having completed secondary school, 18.0% having completed vocational training, 19.4% having a school degree that allowed them to attend university, and 59.0% having completed a university degree. Most participants (72.8%) were currently employed or self-employed, 8.5% were students, attending school, vocational training, military service, or an internship, 15.3% were currently not working (e.g., retired or looking for a job), and 3.4% did not answer the question on their employment status.

Instruments

The VIA-IS (Peterson et al. 2005a; in the German adaption by Ruch et al. 2010b) is the standard instrument for the assessment of the 24 character strengths (10 items per strength) of the VIA classification (Peterson and Seligman 2004) in the German-speaking area. All items are positively keyed and answered on a 5-point Likert-style scale (from 5 = “very much like me” to 1 = “very much unlike me”). A sample item is “I find the world a very interesting place” (curiosity). The German version of the VIA-IS has often been used in research studies that supported its sound psychometric properties (e.g., Martínez-Martí and Ruch 2017a; Ruch et al. 2017). Internal consistencies in the present study were satisfactory and ranged from α = .72 (kindness) to α = .91 (spirituality), median: α = .79.

The Orientations to Happiness questionnaire (OTH; Peterson et al. 2005b; in the German adaption by Ruch et al. 2010a) is a 18 item self-report questionnaire for the assessment of three approaches to well-being as suggested in Seligman’s (2002) authentic happiness theory: the pursuit of pleasure, the pursuit of engagement, and the pursuit of meaning (6 items per scale). All items in the OTH are positively keyed and use a 5-point Likert-style scale (from 1 = “very much unlike me” to 5 = “very much like me”). A sample item is “I seek out situations that challenge my skills and abilities” (engagement). The OTH has been frequently used in research in diverse settings (e.g., Isler and Newland 2017; Martínez-Martí and Ruch 2017b; Proyer et al. 2016). As suggested by Gander et al. (2017), each OTH scale was shortened by one item when used together with the short scales for the assessment of positive relationships and accomplishment. Internal consistencies in the present study were acceptable and comparable to earlier findings (pleasure: α = .68, engagement: α = .65, meaning: α = .75).

The short scales for the assessment of positive relationships and accomplishment (Gander et al. 2017) are self-report scales for the assessment of the orientation towards positive relationships and accomplishment with 5 items each. Together with the OTH, they can be used to assess the endorsement of each of the PERMA dimensions in Seligman’s (2011) well-being theory. All items use the same response format as the OTH (5-point Likert-style scale ranging from 1 = “very much unlike me” to 5 = “very much like me”). A sample item is “A good life means to me that I can share it with others” (positive relationships). Gander et al. (2017) showed that the scales were well-represented by the intended factorial model, were not redundant with the OTH factors, predicted relevant external criteria above the influence of the OTH dimensions (e.g., life satisfaction), and were stable over longer time periods (6 months), but still amenable for change. In the present study, internal consistencies for these scales were satisfactory (positive relationships: α = .76, accomplishment: α = .71).

Procedure

Participants were recruited within a larger project to participate in a one-week online strengths-based positive psychology intervention (see Gander et al. 2016) by means of online-advertisement (forums, mailing lists etc.) and university press releases on other (unrelated) studies. The data used here were collected as part of the baseline assessment using an online survey, before the start of the intervention. Participants received an individual feedback on their character strengths and well-being after completion of the intervention as a method of incentivizing their participation. Participants gave informed consent and an ethics committee approved the study.

Results

Relationships Between Self-Rated Character Strengths and PERMA Dimensions

Firstly, we examined the relationships between the self-ratings of both character strengths and orientations to the PERMA dimensions while controlling for gender and age (see Table A1 for means, standard deviations, and correlations with gender and age). In addition, we examined the shared variance between the character strengths and the orientations to well-being by predicting one’s level of each of the 24 character strengths by all PERMA dimensions and vice versa, while controlling for age and gender. Results are given in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that — with the exception of modesty and prudence — all character strengths were positively related to all PERMA dimensions with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Overall, the pursuit of engagement, meaning, and accomplishment were predicted best by character strengths, with close to or over 40% of shared variance. The pursuit of pleasure and positive relationships was still predicted well (29% and 26% shared variance, respectively).

When rank ordering the correlation coefficients numerically from highest to lowest, pleasure was predicted best by the strengths of zest, humor, hope, and curiosity (all at least medium effects; in descending order). Engagement showed the strongest relationships with persistence, zest, hope, curiosity, bravery, love of learning, and leadership. Positive relationships were mostly related to teamwork, love, and kindness (medium to large effects). Meaning was predominantly related to spirituality (large effect), but also showed at least medium-sized relationships to gratitude, hope, leadership, curiosity, zest, appreciation of beauty and excellence, and creativity. Finally, accomplishment was mostly related to hope, persistence, and zest (large effects), but also to curiosity, bravery, perspective, love, love of learning, leadership, social intelligence, and self-regulation (at least medium-sized effects). Thus, whereas strengths such as zest, hope, and curiosity were among the strongest predictors for most PERMA dimensions (i.e., all with the exception of positive relationships), other strengths were most strongly related to only one of the dimensions: For example, humor went along with pleasure, teamwork with positive relationships, spirituality with meaning, and persistence with both engagement and accomplishment. Overall, engagement and accomplishment showed a rather similar correlational pattern with character strengths.

Cluster Analysis

In addition to the variable-centered approach, we applied a person-centered approach and compared the levels of character strengths among different prototypes of people with regard to their orientations to the PERMA dimensions. Therefore, we computed cluster analyses according to the procedure described by Asendorpf et al. (2001). Firstly, Ward’s hierarchical clustering procedure was applied (using squared Euclidean distances), suggesting a two- or a four-cluster solution. In line with previous findings (Avsec et al. 2016), we decided to proceed with a four-cluster solution. Secondly, the cluster-centers of the four-cluster solution were used in a non-hierarchical clustering procedure (k-means). We tested the replicability of the solution by splitting the full sample in two random subsamples and conducting both steps separately for both subsamples in a first step, and by classifying both subsamples again based on the cluster-centers of the other subsample (using the k-means procedure) in a second step. Then, we estimated the agreement between the original classification and the cross-classification by Cohen’s Kappa. This step was repeated with ten different random splits. Results showed that the reliability of the four-factor solution was rather high (median κ = .89; ranging from κ = .77 to κ = .93). We analyzed the cluster centers for the interpretation of the results (Table 2).

Table 2 shows that the first cluster was characterized by high scores in all PERMA dimensions (tentatively labeled flourishers), whereas the fourth cluster showed low scores in all PERMA dimensions (languishers). People in the second cluster were characterized by slightly elevated scores in engagement, meaning, and accomplishment, and reduced scores in positive relationships and pleasure (unsocial eudemonics). The third cluster showed the opposite pattern: Elevated scores in positive relationships and pleasure, and reduced scores in the other dimensions (social hedonics).

Next, we analyzed the mean-level differences in character strengths among the four prototypes by conducting a MANCOVA analysis (dependent = 24 character strengths, factor = cluster membership, controlling for age and gender). Results revealed a large effect for cluster membership across all strengths (Pillai’s trace = .53, F[72, 16,482] = 49.47, p < .001, partial η2 = .18). This difference between clusters persisted for all strengths, when analyzed in separate ANCOVAs (dependent = strength, factor = cluster membership, controlled for age and gender). Corrected means, standard deviations, and results of ANCOVA analyses and post-hoc tests are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that for 14 out of the 24 strengths, all clusters differed from each other. For most of these strengths, the flourishers reported the highest scores, followed by the unsocial eudemonics, the social hedonics, and the languishers. For those strengths especially related to social interactions however (i.e., love, kindness, teamwork, and humor), the social hedonics showed higher scores than the unsocial eudemonics. In another large group of strengths (i.e., 7 out of 24), the unsocial eudemonics did not differ from the social hedonics, while the flourishers still showed higher levels and the languishers showed lower levels than unsocial eudemonics and social hedonics did. The only deviation from this general pattern was observed for the strength of modesty where languishers and social hedonics scored higher than flourishers and unsocial eudemonics.

Discussion

Study 1 aimed at replicating previous findings on the relationships between character strengths and the orientations to pleasure, engagement, and meaning, while also considering the orientations to positive relationships and accomplishment and applying both a variable-centered and a person-centered approach.

Results widely confirmed previous findings with regard to pleasure, engagement, and meaning and were also in line with expectations for the orientations to positive relationships and accomplishment; both were positively related to all strengths (with the exception of modesty), and showed differential relationships with specific strengths (e.g., positive relationships was better predicted by teamwork or kindness, while accomplishment was better predicted by persistence than most other orientations). Overall, the findings support the first criterion for character strengths by validating one of the basic assumptions, namely that they should relate to the good life. Overall, there are several strengths that go along with all orientations to well-being, mostly zest, hope, and gratitude. Consequently, it might be generally beneficial to build these strengths – regardless of what approach to well-being one is pursuing.

The person-centered approach offered a new view on the PERMA-dimensions. We identified four prototypes of people, characterized by high or low scores in all orientations (flourishers and languishers, respectively), but also two types characterized by increased levels of pleasure and positive relationships, and reduced levels of engagement, meaning, and accomplishment (social hedonics), and vice versa (unsocial eudemonics). Overall, the obtained clusters were somewhat similar to those reported in previous studies that did not take into account the orientations to relationships and accomplishment (Kavčič and Avsec 2014; Avsec et al. 2016). While flourishers were characterized by high levels in all strengths and languishers showed low levels in all strengths, social hedonics and unsocial eudemonics were mostly separated by their levels in interpersonal strengths such as teamwork, love, humor, and kindness. Thus, although all orientations to well-being are positively related to each other, there are certain combinations that occur more often than others. This is also well-reflected in specific strengths profiles, which lends further support to the notion that character goes along with the good life.

The interpretation of this study’s results is limited by the exclusive use of self-reported data. This might have resulted in an inflation of the relationships between the two sets of constructs due to common method bias. For this purpose, a second study on the variable-centered approach was conducted that used different assessment methods.

Study 2

In an effort to overcome a possible common method bias when correlating two self-report measures, we examined self- and informant-ratings of both the orientations to the PERMA dimensions and character strengths. While the same measures were used for self-ratings as in Study 1, we used a short form for the assessment of informant-rated character strengths (CSRF; Character Strengths Rating Form, Ruch et al. 2014) in order to reduce the effort required from informant-raters. In line with previous findings (Buschor et al. 2013), we expected weaker relationships when analyzing the relationships using different methods, but overall similar findings as in Study 1.

Method

Participants

The sample of self-raters consisted of N = 172 (81.4% female) participants. Their mean age was 27.78 years (SD = 12.19), ranging from 18 to 66 years. The majority of the participants (72.1%) indicated living in Switzerland, 23.8% in Germany and 4.1% in other countries. Regarding their highest level of education, 1.7% indicated still going to school, 1.7% having completed secondary school, 9.3% having completed vocational training, 61.6% having a school degree that allowed them to attend university, and 25.6% having completed a university degree. The majority of participants (72.1%) were students, 22.1% were currently employed or self-employed, 2.9% were attending school or vocational training, and 2.9% were currently not working (e.g., retired or looking for a job). Self-raters recruited on average 1.96 informant-raters (SD = 0.53): 14.0% recruited one, 78.5% recruited two, 5.2% recruited three, and 2.3% recruited four informant-raters.

Consequently, the sample of informant-raters consisted of N = 337 (63.5% female) participants. Their mean age was 35.61 years (SD = 16.04), ranging from 14 to 77 years. The majority of them (69.7%) indicated living in Switzerland, 24.0% in Germany, 5.4% in other countries, and 0.9% did not indicate their country of residence.

The informant-raters knew the self-raters for an average of 16.12 years (SD = 10.47), ranging from 1 to 50 years. The largest group of informant-raters (35.3%) were friends with the self-raters, 27.0% were parents or children, 18.4% romantic partners, 13.4% siblings, 3.3% other relatives (e.g., cousins), and 2.7% indicated a different relationship (e.g., roommates). On a scale from 1 = “not close at all” to 7 = “extremely close”, informant-raters described their level of closeness on average as “very close” (M = 6.18, SD = 0.74, Min = 4). The majority (85.7%) indicated that their relationship to the self-rater was either “very close” or “extremely close”.

Instruments

To assess character strengths in self-ratings, we used the VIA-IS in the German adaptation by Ruch et al. (2010b). In the present study, the 24 scales reached internal consistencies ranging from α = .73 (leadership and self-regulation) to α = .91 (spirituality), with a median of α = .80.

For the informant-ratings, an adapted version of the Character Strengths Rating Form (CSRF; Ruch et al. 2014) was used. The CSRF assesses the 24 character strengths described in the VIA classification (Peterson and Seligman 2004) using a single rating for each strength. These ratings describe the respective character strength; for example, “Prudence: Prudent people think carefully about the consequences of their choices before acting. They do not say or do things that might later be regretted.” For the purpose of this study, the 9-point response format was adapted to be used in an informant-rating form (ranging from 1 = “not like him/her at all” to 9 = “absolutely like him/her”). Ruch et al. (2014) reported a medium to high convergence with the VIA-IS (correlations ranging from r = .41 to r = .77). In the present study, the informant-ratings using the CSRF and the self ratings using the VIA-IS converged as expected: The correlations reached an average of r(170) = .34 and ranged from r(170) = .22 for leadership to r(170) = .67 for spirituality (all p < .01), which was comparable to the correlations between self- and informant-ratings in the VIA-IS reported previously (median r = .29 in Buschor et al. 2013).

To assess the orientations to well-being in both self- and informant-ratings, the Orientations to Happiness questionnaire in the German adaptation by Ruch et al. (2010a) and the short scales for the assessment of the endorsement of positive relationships and accomplishment (Gander et al. 2017) as described in Study 1 were used. In the present sample, internal consistency coefficients for the self-ratings were comparable to previous studies and yielded coefficients of α = .65 (pleasure), α = .62 (engagement), α = .78 (positive relationships), α = .67 (meaning), and α = .65 (accomplishment). For the informant-ratings, alpha coefficients were similar: α = .66 (pleasure), α = .65 (engagement), α = .78 (positive relationships), α = .67 (meaning), and α = .71 (accomplishment). Correlations between the self- and informant-rated scales were medium to high: r (170) = .36 for pleasure, r (170) = .40 for engagement, r (170) = .52 for positive relationships, r (170) = .40 for meaning, and r (170) = .38 for accomplishment (all p < .001).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via university mailing lists, social media, and personal contacts. Initially, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, data privacy, and the voluntary nature of participation and they gave their consent to participate. The results reported here were collected as part of a larger study using an online survey. Only participants who indicated that they had answered the questions seriously, that they encountered no problems in answering the questions based on language comprehension were included in the analyses. Further, at least one informant-rating had be matched to the self-rating and at least a moderate level of closeness had to be indicated, i.e., a rating ≥ 4 on the 7-point scale assessing closeness. For all self-raters that provided more than one informant-rating, the informant-ratings were averaged. Excluding the participants who provided only one informant-rating affected the results only marginally– therefore we decided to include them. The participants were not compensated, but self-raters could obtain partial course credit and were offered an individual feedback on their character strengths. According to the university’s guideline, no ethics approval was required for this study.

Results

Relationships Between Self-Rated Character Strengths and Self-Rated Orientations to Well-Being

First, we aimed to replicate the findings of Study 1 on the relationships between self-rated character strengths and self-rated orientations to well-being (see Table A2 in the online supplementary section). The partial correlations (controlling for age and gender) showed overall a similar pattern as reported in previous studies and in Study 1. The amount of shared variance between character strengths and orientations to well-being was around 50% for all five orientations (Table A2).

Relationships Between Self-Rated Character Strengths and Informant-Rated Orientations to Well-Being

The relationships as well as the amount of shared variance between self-rated character strengths and the informant-rated PERMA dimensions controlling for age and gender are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that pleasure showed the strongest relationships with gratitude and humor (at least medium-sized correlations). Engagement was most strongly associated with curiosity, gratitude, zest, hope, and spirituality (at least medium-sized correlations). Positive relationships were best predicted by teamwork, love, and kindness (medium to large effects). Meaning was mostly related to spirituality, curiosity, and gratitude (at least medium-sized correlations). Accomplishment showed the strongest relationships with zest and persistence (at least medium-sized correlations). Notably, there was also one negative correlation that reached statistical significance, namely between love of learning and positive relationships. However, this correlation was small in size (r[168] = −.16, p < .05).

Relationships Between Informant-Rated Character Strengths and Self and Informant-Rated Orientations to Well-Being

Partial correlations (again controlling for age and gender) between informant-ratings of character strengths and both self- and informant-rated orientations to well-being were also computed. These correlations mostly corroborated previously reported findings and are therefore not given in detail (see online supplementary Tables A3 and A4).

Discussion

In Study 2, we examined the relationships between character strengths and orientations to well-being using both self- and informant reports of both sets of constructs. Overall, the results show that the relationships — as established in Study 1 — are replicable also when using different data sources (self- and informant-reports) and different instruments for assessing character strengths (VIA-IS and the short measure CSRF). Overall, the amount of shared variance between character strengths and orientations to well-being was lowest when considering the relationships using both informant-rated character strengths and self-rated orientations to well-being (see Table A3). This might partially be explained by the use of the CSRF, which consists of only one item per character strength and is thus a less reliable measure than the VIA-IS. Consequently, some of the associations that were at least medium-sized in the other combinations of self- and informant-ratings did not reach statistical significance, such as the correlations between social intelligence and positive relationships or between hope and accomplishment.

Several limitations of Study 2 also have to be noted. Firstly, the number of informant-raters per participant differed, and although the majority of participants had two or more informant-ratings, some participants only provided one, which yielded a less reliable estimate. Also, although informants were in general very close to the self-raters, we did not account for the intensity, the length, or the type of the relationship. Nonetheless, the convergence of the different approaches suggests that the relationships between character strengths and the orientations to well-being are rather robust.

General Discussion

The present studies investigated the relationships between character strengths and Seligman’s (2011) multidimensional framework of well-being. In both a large sample of self-reports and a second sample using different data sources (i.e., self- and informant-reports), we observed meaningful relationships between the two sets of constructs that are in line with previous results for the three orientations to happiness (pleasure, engagement, and meaning) and in line with our expectations for the two additional orientations to positive relationships and to accomplishment. Additionally, in a person-centered analysis, we established a four-cluster solution distinguishing languishers (low on all orientations), unsocial eudemonics (lower on pleasure and positive relationships and higher on engagement, meaning, and accomplishment), social hedonics (showing the opposite pattern as unsocial eudemonics), and flourishers (high on all orientations) with the clusters relating differentially to character strengths.

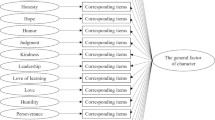

When taking the results of both studies together, we can draw conclusions about the relationships between the 24 character strengths of the VIA classification and the five orientations to well-being that were replicated across the different samples and the different methods. Table 5 summarizes the pattern of correlations that we found across the two studies.

As displayed in Table 5, between three and seven character strengths were positively related to one of the PERMA orientations across all analyses in both studies (i. e., in Study 1 and all combinations of self- and informant-ratings in Study 2). An additional four to ten character strengths showed positive correlations in Study 1 and in three out of the four possible combinations in Study 2 (for example, the correlation between creativity and pleasure was significant in all cases but the correlation between informant-rated character strengths and self-rated orientations failed to reach statistical significance). Finally, we also included those associations that appeared in Study 1 and two out of the four combinations in Study 2. This was true for between three and eight additional character strengths for each orientation. Overall, all character strengths in the VIA classification were involved in the prediction of at least one of the five orientations to well-being. Also, while engagement, meaning, and accomplishment were overall numerically better predicted by the strengths than pleasure and positive relationships in self-ratings, this was not the case in Study 2 whereby with informant-ratings considered, the explained variance by strengths was more similar across the PERMA dimensions. Thus, the relationships between strengths and the PERMA dimensions were very consistent across studies and samples – only very few character strengths showed strong relationships with a PERMA dimension in only one or two of the tests, but not in others. These findings lend support to the notion that all character strengths underpin the orientations. Further, the relationships of character strengths to the PERMA dimensions are not specific, but most character strengths are involved in the prediction of several PERMA dimensions, which is also consistent with expectations (Seligman 2011).

All in all, pleasure was most consistently (i.e., significant relationships across all analyses) associated with zest, hope, and humor. These three strengths have already shown the strongest associations with the disposition to experience specific positive emotions, such as joy, contentment, pride, or amusement (Güsewell and Ruch 2012). Engagement showed the most consistent relationships with creativity, curiosity, love of learning, persistence, zest, leadership, and self-regulation. This is in line with theoretical assumptions and findings regarding the correlates of dispositional flow (e.g., Baumann 2012; Teng 2011). Positive relationships showed a very consistent pattern of correlations across the different samples and methods, with the three character strengths of love, kindness, and teamwork standing out as the most important predictors. These three character strengths can be seen to be conducive to initiating and maintaining relationships. Whereas love might be especially relevant in romantic relationships and has been found to be related to the partners’ life satisfaction in adolescents (Weber and Ruch 2012), kindness and teamwork might be crucial for non-romantic relationships, such as in friendships (Wagner 2018) or in work teams, and have been reported to predict positive interpersonal behaviors at work or loyalty to the organization (e.g., Harzer and Ruch 2014; Ruch et al. 2018).

Curiosity, perspective, social intelligence, appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, and — with the largest effect size — spirituality were consistently related to meaning. Spirituality and appreciation of beauty and excellence might be important sources of meaning for many people, and curiosity might motivate people to search for a meaning in their lives. Gratitude has been shown to predict increases in meaning (Kleiman et al. 2013), and might, as well as social intelligence, facilitate the forming of close social bonds that also provide meaning.

Finally, accomplishment showed consistent associations with perspective, persistence, and zest. All three strengths have also been related to school achievement (i.e., grade point average; Wagner and Ruch 2015), while persistence was the best predictor among the strengths for task performance at work (Harzer and Ruch 2014). One might assume that perspective is required in order to set appropriate long-term goals, while persistence and zest are necessary in order to maintain goal pursuit and facilitate goal attainment.

Across both studies, engagement and accomplishment showed similar patterns of relationships with character strengths. This is not surprising, since both engagement and accomplishment are related to task completion: While engagement focuses on the process (i.e., experiences during task completion), accomplishment refers more strongly to the results. Therefore, both can be expected to yield similar relationships to a broad array of constructs. Nonetheless, it has been shown that engagement and accomplishment can be distinguished from each other both on a conceptual and empirical basis (e.g., Gander et al. 2017).

Peterson et al. (2007) as well as Buschor et al. (2013) concluded that those character strengths that typically show the highest correlations with life satisfaction (curiosity, zest, love, gratitude, and hope) were also most strongly associated with the orientations to pleasure/positive emotions, engagement, and meaning. These findings were widely replicated and extended to the two new orientations: In self-ratings, all these five character strengths were explained best by the orientations to well-being; the only exceptions were the strengths of persistence and spirituality which overall showed stronger associations (i.e., more shared variance) with all PERMA dimensions than curiosity, love, and gratitude did. However, this was mainly due to their strong relationships to engagement and accomplishment (persistence) and meaning (spirituality) whereas the other strengths showed strong relationships to almost all orientations to well-being. Similar findings were obtained in informant-ratings, where gratitude, curiosity, and love were explained best by PERMA when compared to other character strengths – only outperformed by teamwork due to its strong association with positive relationships, and spirituality due to its strong relation to meaning. However, the strength of hope yielded comparably weaker relationships to the orientations to well-being overall, but was still related consistently with four of the five orientations to well-being (with the exception of positive relationships). When considering the person-centered analysis in Study 1, all five strengths were clearly highest among flourishers, and the effect sizes underline that the difference between the clusters was larger for these five strengths than for most other strengths.

Some strengths (e.g., mostly modesty and prudence) were unrelated to some orientations to well-being, and showed, in some combinations, small negative relationships to specific PERMA dimensions. We assume that these strengths (and also the other strengths of temperance; i.e., forgiveness, and self-regulation) do not necessarily contribute to the good life for oneself, but may be helpful for avoiding negative experiences and for contributing to the good life of others. Thus, they might represent valuable traits for the benefit of social groups and systems. However, this should be further examined in future studies. In addition, it would be interesting to test Seligman’s (2011) hypothesis that while all 24 character strengths foster all five orientations to well-being, the highest strengths of an individual might also play an important role for well-being (e.g., Proyer et al. 2015). Future studies might examine these questions in intervention studies that would also allow for testing directional and causal relationships between character strengths and the PERMA dimensions that can, of course, not be examined in the here reported cross-sectional studies. Nonetheless, the present findings might guide interventions aimed at increasing well-being overall (i.e., attaining high scores in all PERMA dimensions) or specific PERMA dimensions. For fostering well-being overall, the group of strengths known to show the strongest relationships to life satisfaction, that is curiosity, zest, love, gratitude, and hope, could be trained (cf. Proyer et al. 2013; see also Gander et al. 2019 in this special issue). For guiding strengths-based interventions for specific PERMA dimensions, we recommend considering the strengths mentioned in Table 5.

Overall, the present set of two studies showed that character strengths are robustly associated with different orientations to the good life in terms of the PERMA framework, and that these associations are replicable across different samples and methods. Our findings extend previous knowledge by considering a broader framework of well-being that goes beyond indicators of subjective/hedonic well-being and thereby provide an important addition to the guidance of strengths-based intervention studies in a broad array of settings, such as in the school or the vocational context (see for example Huber et al. 2019, or Strecker et al. 2019 in this special issue).

References

Allport, G. W. (1921). Personality and character. Psychological Bulletin, 18, 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0066265.

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & van Aken, M. A. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.408.

Avsec, A., Kavčič, T., & Jarden, A. (2016). Synergistic paths to happiness: Findings from seven countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 1371–1390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9648-2.

Baumann, N. (2012). Autotelic personality. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 165–186). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2359-1_9.

Baumann, D., Ruch, W., Margelisch, K., Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2019). Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: an analysis of different living conditions. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9689-x.

Berthold, A., & Ruch, W. (2014). Satisfaction with life and character strengths of non-religious and religious people: it’s practicing one’s religion that makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(876). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00876.

Buschor, C., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2013). Self- and peer-rated character strengths: how do they relate to satisfaction with life and orientations to happiness? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.758305.

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2016). Positive psychology interventions addressing pleasure, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment increase well-being and ameliorate depressive symptoms: A randomized, placebo-controlled online study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(686). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00686.

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2017). The subjective assessment of accomplishment and positive relationships: initial validation and correlative and experimental evidence for their association with well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9751-z.

Gander, F., Hofmann, J., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2019). Character strengths – Stability, change, and relationships with well-being changes. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9690-4.

Ghielen, S. T. S., Woerkom, M. van, & Meyers, M. C. (2017). Promoting positive outcomes through strengths interventions: a literature review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1365164.

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., & Kauffman, S. B. (2017). Measuring well-being: A comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434.

Güsewell, A., & Ruch, W. (2012). Are only emotional strengths emotional? Character strengths and disposition to positive emotions. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 4, 218–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2012.01070.x.

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2014). The role of character strengths for task performance, job dedication, interpersonal facilitation, and organizational support. Human Performance, 27, 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2014.913592.

Hausler, M., Strecker, C., Huber, A., Brenner, M., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2017). Distinguishing relational aspects of character strengths with subjective and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01159.

Höfer, S., Gander, F., Höge, T., & Ruch, W. (2019). Special issue: Character strengths, well-being, and health in educational and vocational settings. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9688-y.

Huber, A., Strecker, C., Hausler, M., Kachel, T., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2019). Possession and applicability of signature character strengths: What is essential for well-being, work engagement, and burnout? Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9699-8.

Huta, V., & Waterman, A. S. (2014). Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1425–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0.

Isler, R. B., & Newland, S. A. (2017). Life satisfaction, well-being and safe driving behaviour in undergraduate psychology students. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 47, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.04.010.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality, second edition: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Johnston, C. S., Luciano, E. C., Maggiori, C., Ruch, W., & Rossier, J. (2013). Validation of the German version of the career adapt-abilities scale and its relation to orientations to happiness and work stress. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.002.

Kavčič, T., & Avsec, A. (2014). Happiness and pathways to reach it: Dimension-centered versus personcentered approach. Social Indicators Research, 118, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0411-y.

Kleiman, E. M., Adams, L. M., Kashdan, T. B., & Riskind, J. H. (2013). Gratitude and grit indirectly reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: Evidence for a mediated moderation model. Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.007.

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1879–1890. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002674.

Martínez-Martí, M. L., & Ruch, W. (2017a). Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1163403.

Martínez-Martí, M. L., & Ruch, W. (2017b). The relationship between orientations to happiness and job satisfaction one year later in a representative sample of employees in Switzerland. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9714-4.

McGrath, R. E. (2014). Scale- and item-level factor analyses of the VIA inventory of strengths. Assessment, 21, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112450612.

Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i2.2.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. (2005a). Assessment of character strengths. In G. P. Koocher, J. C. Norcross, & S. S. Hill III (Eds.), Psychologists’ desk reference (Vol. 3, 2nd ed., pp. 93–98). New York: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005b). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z.

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701228938.

Proyer, R. T., Annen, H., Eggimann, N., Schneider, A., & Ruch, W. (2012). Assessing the “good life” in a military context: how does life and work-satisfaction relate to orientations to happiness and career-success among Swiss professional officers? Social Indicators Research, 106, 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9823-8.

Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Buschor, C. (2013). Testing strengths-based interventions: A preliminary study on the effectiveness of a program targeting curiosity, gratitude, hope, humor, and zest for enhancing life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9331-9.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2015). Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term effects for a signature strengths- vs. a lesser strengths-intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(456). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2016). Addressing the role of personality, ability, and positive and negative affect in positive psychology interventions: Findings from a randomized intervention based on the authentic happiness theory and extensions. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137622.

Ruch, W., & Proyer, R. T. (2015). Mapping strengths into virtues: the relation of the 24 VIA-strengths to six ubiquitous virtues. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(460). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00460.

Ruch, W., Harzer, C., Proyer, R. T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2010a). Ways to happiness in German-speaking countries: the adaptation of the German version of the orientations to happiness questionnaire in paper-pencil and internet samples. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000030.

Ruch, W., Proyer, R. T., Harzer, C., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2010b). Values in action inventory of strengths (VIA-IS): adaptation and validation of the German version and the development of a peer-rating form. Journal of Individual Differences, 31, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000022.

Ruch, W., Martínez-Martí, M. L., Proyer, R. T., & Harzer, C. (2014). The character strengths rating form (CSRF): development and initial assessment of a 24-item rating scale to assess character strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.042.

Ruch, W., Bruntsch, R., & Wagner, L. (2017). The role of character traits in economic games. Personality and Individual Differences, 108(Supplement C), 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.007.

Ruch, W., Gander, F., Platt, T., & Hofmann, J. (2018). Team roles: their relationships to character strengths and job satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1257051.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish. New York: Free Press.

Slavin, S. J., Schindler, D., Chibnall, J. T., Fendell, G., & Shoss, M. (2012). PERMA: a model for institutional leadership and culture change. Academic Medicine, 87, 1481. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826c525a.

Strecker, C., Hausler, M., Huber, A., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2019). Identifying thriving workplaces in hospitals: Work characteristics and the applicability of character strengths at work. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9693-1.

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 6, 251–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12027.

Teng, C.-I. (2011). Who are likely to experience flow? Impact of temperament and character on flow. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 863–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.012.

Wagner, L. (2018). Good character is what we look for in a friend: Character strengths are positively related to peer acceptance and friendship quality in early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618791286.

Wagner, L., & Ruch, W. (2015). Good character at school: Positive classroom behavior mediates the link between character strengths and school achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(610). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00610.

Weber, M., & Ruch, W. (2012). The role of character strengths in adolescent romantic relationships: an initial study on partner selection and mates’ life satisfaction. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.002.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF; grants 100014_132512 and 100014_149772 awarded to RP and WR, and 100014_172723 awarded to WR). The authors thank Sara Wellenzohn and Sarah Frankenthal for their help with data collection and Mara Stewart for proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 53.6 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R.T. et al. Character Strengths and PERMA: Investigating the Relationships of Character Strengths with a Multidimensional Framework of Well-Being. Applied Research Quality Life 15, 307–328 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9695-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9695-z