Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to explore the ways people achieve their happiness employing two approaches, i.e. a dimension-centred, focusing on the three orientations to happiness (orientation to pleasure, meaning, and engagement), and a person-centred, focusing on patterns of these three orientations within individuals. The predictive validity of individual orientations to happiness and their characteristic patterns for three aspects of subjective well-being was explored. Adult participants (N = 1,142; 33 % male) filled-in the Orientations to Happiness Questionnaire and the Mental Health Continuum-Long Form. Applying the dimension-centred approach, results suggested that all of the orientations represent possible and appropriate ways to achieve happiness. Person-centred analysis yielded four groups of individuals with similar profiles of ways towards happiness and membership of these groups was associated with individual’s well-being. Leading an empty life was associated with the poorest outcomes and full life with the highest well-being, with moderate well-being characterizing individuals pursuing pleasurable and meaningful life. More precisely, pleasurable life and meaningful life had relatively similar predictive value for psychological well-being but demonstrated discriminant validity for emotional and social well-being. This suggests that the profiles are meaningfully different and highlights the importance of the multiplicative influences of the three specific orientations to happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

People have long been concerned with the good life and how it can be achieved. The theory of Seligman (2002) offers three possibilities—happiness can be reached through pleasure, meaning or engagement. Though each of these three orientations presents a possible path to happiness, individuals usually manifest a pattern of all three orientations in their searching of good life and happiness (Peterson et al. 2005). The present study aimed at exploring whether replicable patterns of the three orientations to happiness can be identified within individuals and how they are related to different aspects of subjective well-being.

1.1 Three Pathways to Happiness

Seligman (2002) originates two of the three orientations to happiness in well-known philosophical approaches to happiness. Increasing happiness through pleasure or positive emotions pertains to a hedonic tradition. According to this tradition, individual`s goal in life is to experience the maximum amount of pleasure and the minimum amount of pain, whereas happiness is the totality of one’s hedonic moments (Ryan and Deci 2001). From the individual’s phenomenological view, the hedonia is usually the most salient aspect of happiness (Seligman et al. 2005). Many studies found the benefits of experiencing positive emotions, including experiencing more positive emotions in the future (Fredrickson and Joiner 2002), a broadened scope of attention and thought-action repertoire (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005), greater life satisfaction (Cohn et al. 2009), and greater well-being in the future (Catalino and Fredrickson 2011).

According to Seligman (2002), the second orientation to happiness gives life meaning. It pertains to using individual’s strengths “to belong to and in the service of something larger than ourselves—something such as knowledge, goodness, family, community, politics, justice, or a higher spiritual power” (Seligman et al. 2005; p. 278). This orientation is based on the eudaimonic tradition, emphasizing that happiness and subjective well-being result from engagement in meaningful activities and actualization of individual’s human potentials (Ryan and Deci 2001). Similarly, Waterman (1993) argues that eudaimonia is present when individual’s activities are congruent with his/her most basic values and are incorporated into his/her actions. High levels of purpose in life seem to be related to psychological and health benefits, including subjective well-being (Schueller and Seligman 2010), cognitive-affective feelings of significance and appreciation, becoming engaged and feeling connected with a broader whole (Huta and Ryan 2010), better neuroendocrine regulation, better immune function, lower cardiovascular risk, better sleep, and more adaptive neural circuitry (for a review, see Ryff and Singer 2008).

The third orientation—engagement—involves the pursuit of “gratification” (Seligman et al. 2005) and is based upon Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) conception of flow. Flow relates to the experience of complete absorption into activity. It occurs in the presence of an optimal balance between individual’s abilities and demands of the situation. The state of flow is so gratifying or autotelic for an individual that it represents a source of intrinsic motivation for the activity. In the long run, flow can lead to higher subjective well-being, although positive emotions are not necessary present at the moment of flow (Seligman et al. 2005). Similarly to the orientation to meaning, the pursuit of engagement relates, for example, to life satisfaction, happiness, and positive affect (Schueller and Seligman 2010). In addition, it is also associated with vocational identity achievement in adolescents (Hirschi 2011), and (weakly) to education and occupational attainment (Schueller and Seligman 2010).

The theoretical and empirical distinctiveness of the orientation to engagement from hedonia and eudaimonia is still the object of an on-going debate. Waterman (1993) for example, hypothesized that experience of flow could be equated with eudaimonia (personal expressiveness). However, on the basis of empirical findings he concluded that flow is not distinct from hedonia and eudaimonia, but is a state that can be characterised by both hedonic and eudaimonic behaviour. The possible problematic differential validity of the engagement scale is warranted also by documented validation studies of the Orientations to Happiness questionnaire (OTH; Peterson et al. 2005), showing the cross saturation of some items of the engagement scale (e.g., Avsec and Kavčič 2012; Chen 2010; Chen et al. 2009; Ruch et al. 2010). Some studies even suggested that a two-factor structure of the OTH may be more appropriate than the three-factor (Anić 2012).

1.2 Constellations of Orientations to Happiness

Since the introduction of the three orientations to happiness, a possible co-variation of them within individual is presumed (Peterson et al. 2005). Authors posited a theoretically driven and empirically supported notion that the best-off individuals are leading the full life, i.e. engaging high in all three orientations to happiness. They examined this premise by investigating the effects of all possible interactions among the three orientations on well-being. In addition to main effects of individual orientations to happiness, their analysis revealed significant, though small effects of the three-way interaction between the orientations (but not any of the two-way interactions). This effect was replicated by some of the later studies (e.g., Chen 2010). The small effect size of the interaction obtained in these studies may be due to the reduced statistical power after accounting for first-order effects (Cohen et al. 2003), leading to an underestimation of real-world effects. Moreover, it is often impractical to model all higher-order interactions of interest, so a person-centred approach can be used as an alternative way to examine possible co-existing effects of the three orientations to happiness.

The basic assumption of the person-centred or typological approach is that dimensions (i.e. the three orientations to happiness) should not be studied in isolation, since a pattern of specific dimensions within individuals adds valuable information about their functioning (for an overview see e.g., Hart et al. 2003; Mervielde and Asendorpf 2000). With person-centred approach groups of individuals who have similar configurations of specific dimensions and thus share the same basic psychic structure and dynamics, can be identified. In comparison to the variable-centred approach, the person-centred approach is rather rare although constantly present in different areas of psychology, from attachment theory (Ainsworth 1985) to work psychology (Holland 1997). Similarly, other sciences commonly use taxonomies to classify the studied subjects (e.g., plants, stars, elements), and not their traits or features.

It should be noted that the predictive power of types in psychology studies is usually not higher than the predictive power of dimensions (Costa et al. 2002; but see Hart et al. 2003), therefore, a person-centred approach should have some other benefits to be used. As already mentioned, this approach is characterized by addressing the intra-individual structure of personality and by descriptive efficiency. In addition, it can facilitate the search for moderator variables, since their effect can often be identified by a differential response of a group of individuals to environmental influences or interventions. And finally, the typological approach has some practical advantages as compared to the dimension-centred approach because lay people generally think of individual differences in terms of types (e.g., “She’s happy”), not dimensions (e. g. “She’s high in emotional and psychological well-being”). Thus, findings concerning types are much easier to communicate to the public than findings concerning dimensions.

1.3 The Importance of Orientations to Happiness for Well-Being

When investigating the predictive value of orientations to happiness, a selection of appropriate criteria variable is of great importance. The most common criteria predicted in previous studies (Chen 2010; Chen et al. 2009; Park et al. 2009; Ruch et al. 2010; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2008) was well-being, usually measured as satisfaction with life (Diener et al. 1985). Authors of the OTH (Peterson et al. 2005) assumed that each orientation is a possible and appropriate path to happiness. Their study showed that all three orientations significantly contribute to the satisfaction with life, jointly explaining 12 % of variance, although the meaning and engagement were more robust predictors compared to the pleasure orientation. Several other studies also suggested that meaning and engagement contribute more to individuals’ well-being than pleasure (e.g., Chen et al. 2009; Kumano 2011; Park et al. 2009; Schueller and Seligman 2010; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2008). In a study by Schueller and Seligman (2010) measures of happiness, positive affect, negative affect, and depression were included as criteria variables in addition to the satisfaction with life. Among the three orientations to happiness, pleasure was the most weakly associated with indicators of well-being, including positive affect. These finding are in contrast to the theoretical expectations and some of the empirical findings (e.g., Vittersø and Søholt 2011) and might indicate the lack of validity of the OTH scale (Henderson et al. 2013).

However, it is dubious that measures used in previous studies can appropriately reflect the whole richness of the well-being construct. For this reason Schueller and Seligman (2010) included also education and occupational attainment as objective measures of well-being, since these two variables are presumed to be intrinsically valuable and representative of well-being. Results indicated that pleasure was negatively, and engagement and meaning were positively related to both objective well-being indicators. Authors concluded that activities increasing engagement and meaning could have the strongest impact on an individual’s well-being since they may increase social and psychological resources, whereas pursuing pleasure may not.

Constructs such as positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction with life relate to hedonic or emotional well-being, while personal growth, self-acceptance, and positive relations with others relate to positive functioning or eudaimonic aspect of well-being (Ryff 1989). We already mentioned that previous studies found that hedonic measures of well-being are associated with engagement and meaning to a higher degree than with pleasure orientation, but it is presumed that engagement and meaning should have even stronger associations with eudaimonic measures of well-being. Keyes’ model (Keyes 2002) incorporates both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being, thus providing suitable criteria variables for our study. In this model, emotional well-being component (positive emotions and satisfaction with life) is considered an indicator of hedonic well-being, while psychological and social well-being are indicators of positive functioning or eudaimonic well-being.

1.4 Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to explore the ways people achieve their happiness employing two approaches, i.e. a dimension-centred, focusing on specific orientations to happiness, and a person-centred, focusing on patterns of orientations within individuals. The study extends previous work by applying a rigorous statistical methodology to directly identify internally replicable combinations of the three pathways to happiness. In addition, our study included a broad measure of subjective well-being, incorporating not only hedonic but also eudaimonic aspects of well-being. As to the dimension-centred approach, we expected that all three orientations would be related to well-being as all of them represent possible and appropriate way to achieve well-being (Seligman 2002). With regard to the person-centred approach, we expected to find groups of individuals with different patterns of the three orientations to happiness. Presumably, full and empty life OTH types would emerge, with other combinations of orientations to happiness possible as well.

In addition, we expected to find significant associations between OTH types obtained and well-being measures. Individuals pursuing all three pathways to happiness were expected to do best and individuals pursuing none to fare the worst. Possible incremental validity of OTH types over and above individual orientations would provide additional value of the person-centred approach.

We also expected that orientations to happiness would be differentially related to the three aspects (emotional, psychological, and social) of well-being. Based on the reviewed studies, we expected meaning and engagement to contribute to psychological and social well-being more than the pleasure orientation. Similarly, we expected that empirically derived OTH types characterized by relatively high levels of meaning and/or engagement orientations would be related to psychological and social well-being.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The present study included 1,142 participants (33 % male, 67 % female), aged 18–91 years (M = 38.2, SD = 15.9 years). Approximately a third of participants finished compulsory schooling (32 %), 23 % finished high school and 45 % had a college (or higher) degree. About 1 % of participants were still attending high school, 26 % were university students, 53 % employed, 6 % unemployed and 12 % retired (2 % missing data). The majority of participants were married (32 %) or cohabiting with their life partner (13 %), 23 % reported to be involved in a romantic relationship but not cohabiting, 26 % identified themselves as single, and 6 % chose the option »other type of romantic involvement«. All participants filled in the OTH, while 30 of them did not complete the MHC-LF questionnaire.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Orientations to Happiness Questionnaire (OTH; Peterson et al. 2005)

The OTH was used as a measure of three possible paths to happiness: pleasure (e.g., For me, the good life is the pleasurable life.), meaning (e.g., My life has a lasting meaning.), and engagement (e.g., I am always very absorbed in what I do.). The questionnaire includes 18 items, 6 tapping each of the three orientations. Using a 5-point rating scale (1 = very much not like me, 5 = very much like me), the participants report how they actually live their life. Scale scores are obtained by summing up ratings on respective items. Previous research in different countries showed that the three scales measuring orientations to happiness are reliable (alphas over 0.62, empirically distinct and have predictive validity for life satisfaction (e.g., Avsec and Kavčič 2012; Peterson et al. 2005; Ruch et al. 2010; Schueller and Seligman 2010). Ruch et al. (2010) also reported on satisfactory temporal stability (rs across 6 months over 0.62) and good convergence between self- and peer-report for all three scales. In the current study, alpha coefficients of internal consistency were satisfactory: 0.83 for pleasure, 0.71 for engagement, and 0.75 for meaning.

2.2.2 Mental Health Continuum-Long Form (MHC-LF; Keyes 2009)

Keyes’ (2002) model of mental health includes three components of well-being: emotional, psychological and social well-being. The first section of MHC-LF measures two aspects of emotional well-being. Positive affect is measured by six items (Mroczek and Kolarz 1998) rated along a 5-point scale (1—none, 5—all of the time), indicating how much of the time during the past 30 days the participant felt cheerful, in good spirits, extremely happy, calm and peaceful, satisfied, and full of life. The result for the positive affect subscale is calculated by averaging the ratings on the six items. The cognitive aspect of emotional well-being is measured as a life satisfaction by a single item of the quality of life overall, rated on a scale from 0 (the worst possible life overall) to 10 (the best possible life overall). The summary score for the emotional well-being scale represents an average value of the standardized positive affect and life satisfaction scores. The second section of MHC-LF comprises Ryff’s (1989) measures of psychological well-being. Six subscales, i.e. self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, and autonomy, include three items each. The third section addresses the social well-being, which is measured by 15 items combining into five subscales (Keyes 1998): social coherence, social integration, social-acceptance, social contribution, and social actualization. The psychological and social well-being scales are responded to on a 7-point rating scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The scale scores are obtained by summing up ratings on the 18 and 15 items, respectively (with some items reversed). The three-factor structure of MHC has been validated (Robitschek and Keyes 2009) and the three well-being scales were found to have satisfactory internal consistency with alphas over 0.80 (Keyes 1998, 2002, 2005; Ryff and Keyes 1995). With the present sample, the three scales showed satisfactory internal consistency with alpha coefficients estimated as 0.88 for emotional well-being, 0.80 for psychological well-being, and 0.81 for social well-being.

2.3 Procedure

The participants completed the OTH and the MHC-LF on a website. The study primarily targeted students of all three Slovene public Universities who then engaged other participants of different ages. In order to ascertain the heterogeneity of the sample, the website was additionally promoted by different means such as press coverage and certain private websites and internet browsers. The participation in the study was voluntary; the respondents were not paid for their partaking, but were provided with an automatically generated feedback on their personal well-being. Before the participants started to fill-in the questionnaires, they were informed about the aims of the research and they gave an informed consent to participate. The data collection lasted approximately 1 year.

2.4 Derivation of OTH Types

In order to derive OTH types, i.e. examine how specific orientations to happiness combine within individuals, we applied a procedure described by Asendorpf et al. (2001) for deriving personality types. This procedure involves a two-step cluster analyses. First, Ward’s hierarchical clustering procedure was performed with z-scores of the three orientations to happiness. Squared Euclidean distances were used as measures of dissimilarities among individuals. Participants were ordered into clusters. Means of the obtained scores for the three dimensions were calculated for each cluster and used as initial cluster centers in the non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis in the second step. Based on previous OTH studies (e.g., Peterson et al. 2005), we expected to find two already established (the full and the empty life types) and at least one additional combination of the three orientations. Therefore, we tested the three-, four-, and five-cluster solutions.

The replicability of the cluster solutions was evaluated following a double-cross validation procedure also described by Asendorpf et al. (2001). The full sample was randomly split into two halves. The two-step clustering procedure (hierarchical Ward method, followed by non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis) was applied to each half, and the individuals in each sub-sample were assigned to their primary clusters. Next, the participants were assigned to their secondary clusters, with the input for the k-means analysis being the initial centers derived through Ward method for the other sub-sample. The two solutions (primary and secondary cluster classifications for each participant) were then compared for agreement with Cohen’s kappa (κ). If necessary, the clusters were reordered so that the content of all the clusters in the first sub-sample corresponded to the content of clusters in the second sub-sample. The two resulting kappas were then averaged. This procedure was repeated 10 times with different random splits of the full sample. The obtained 10 average kappas were then again averaged into a replicability coefficient with the value of at least 0.60 considered as acceptable.

3 Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the three orientations to happiness and for different aspects of mental health. All three orientations to happiness were positively and statistically significantly correlated with emotional, psychological and social well-being with correlation coefficients ranging from low to moderate.

3.1 OTH Types

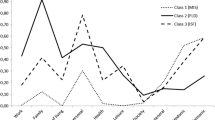

Three-, four-, and five-cluster solutions were investigated with regard to their replicability, interpretability of the profiles obtained, and the distribution of cluster membership. Average Kappa coefficient for the three-cluster solution was 0.59 (range from 0.34 to 0.93), for four-cluster solution 0.90 (range from 0.73 to 0.99) and for five-cluster solution 0.72 (range from 0.46 to 0.98). Thus, the four- and five-cluster solutions were found sufficiently replicable (mean Kappa over 0.60). We opted for the four-cluster solution as it had the highest estimated replicability (all Kappas over 0.60), the obtained four profiles were meaningful and all clusters had substantive membership. Furthermore, the four types differed significantly across orientation to meaning (F = 492.62, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.57), orientation to pleasure (F = 505.71, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.57) and orientation to engagement (F = 432.16, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.53). All of the post hoc paired comparisons (Scheffé’s test) showed significant differences at p < 0.05 across the three orientations with the exception of a non-significant difference in orientation to engagement between second and fourth cluster.

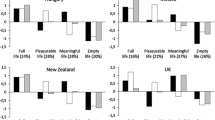

The prototypical characteristics (mean z-scores on the three orientations to happiness) for each of the four clusters are presented in Fig. 1. The first cluster comprised 28 % of the participants (N = 321). It was characterized by high scores (over 0.5 SD above mean) on all three orientations to happiness, thus it was named full life type. The second cluster included 329 participants (29 % of the sample) with high self-ratings on orientation to pleasure, low orientation to meaning and average orientation to engagement. Accordingly, the profile was named pleasurable life type. The third cluster comprising 16 % of the sample (N = 188) was characterized by low mean values on all three orientations (over 1 SD below mean values) and was therefore referred to as empty life type. The remaining 27 % of the sample (N = 304) were categorized in the fourth cluster described by high orientation to meaning, low orientation to pleasure and average orientation to engagement. We labelled this cluster meaningful life type.

3.2 Associations Between OTH Types and Well-Being Measures

For each pattern of orientations to happiness identified, mean z-scores for emotional, psychological, and social well-being were compared by one-way ANOVA (see Table 2). Type membership explained between 11 and 15 % of variance in participants’ well-being.

According to Cohen (1988), the percentages of variance explained indicated by η2 (see the respective column in Table 2) are defined as medium (0.058 < η2 < 0.139) to high. Paired comparisons revealed that participants classified in the full life type reported the highest emotional, psychological and social well-being; the empty life type was characterized by lowest well-being, while the members of the pleasurable and meaningful life types reported on moderate well-being. More precisely, members of pleasurable life type reported on higher emotional well-being than members of meaningful life type (both groups were significantly lower on emotional well-being than full life and significantly higher than empty life). With respect to the psychological well-being, participants leading a pleasurable life did not differ statistically significantly from participants leading a meaningful life, though both groups scored higher than members of empty life and lower than members of full life type. The meaningful life was characterized by similar levels of social well-being as the full life, while both profiles were described by significantly higher social well-being than pleasurable life, which in turn had significantly higher mean social well-being than empty life.

3.3 Predictive Validity of Dimensions Versus Types

We performed two sets of hierarchical regression analyses in order to evaluate (a) the overall predictive value of separate orientations to happiness (three dimensions) and their profiles, and (b) the incremental predictive validity of the dimensions over types and vice versa. First, three dummy-coded variables were introduced to represent the four OTH types with the full life type set as a reference group. Then, two regression models were tested. In the first regression model, the dimensions were entered as predictors at step 1 and the type indicators (dummy-coded variables) were additionally entered as predictors at step 2. In the second model, type indicators were entered in the first step and dimension scores added in the second step. Results of the two regression analyses are summarized in Table 3.

In the first model, the three orientations to happiness alone explained 13–18 % of variance in different aspects of well-being (see Table 3, column Step 1 in Model 1), representing a medium effect size (Cohen 1988). Type indicators explained less than 1 % of additional variance, which represents a rather negligible effect, though the increase in explained variance in social well-being reached the level of statistical significance with alpha set at 0.05. After the second step (with all of the predictors included), emotional and psychological well-being scores were significantly predicted by orientations to meaning (βs 0.11, p < 0.05 and 0.16, p < 0.001, respectively), pleasure (both βs 0.13, p < 0.01) and engagement (βs 0.17, p < 0.001 and 0.20, p < 0.001, respectively). Orientations to meaning (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and engagement (β = 0.18, p < 0.001) contributed significantly to the prediction of social well-being. None of the type indicators emerged as statistically significant predictors (at alpha set at 0.05) of well-being measures.

In the second model, type indicators were entered first and they predicted all of the criteria variables with 11–15 % of variance explained. Following Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, R 2 lower than 0.13 present a small effect size and R 2 between 0.13 and 0.26 reflect medium effect size. Regression coefficients obtained in step 1 indicated that members of the empty, pleasurable, and meaningful life types reported on lower emotional and psychological well-being than the group with full life. Classification into pleasurable and empty life groups was associated also with lower ratings of social well-being as compared to the full life group. Adding the continuous data on the three orientations to happiness led to statistically significant increments in prediction over the types with 2–5 % of additional variance in well-being measures explained. After adding the dimensions, the regression coefficients for type indicators were no longer statistically significant; the specific orientations only were significant predictors of well-being measures (betas the same as in the final model 1).

4 Discussion

The present study showed that individuals’ pathways to happiness can be reliably measured using two approaches, namely dimension- and person-centred approach. Specifically, individuals differ in the degree they pursue each of the specific ways to happiness and in the constellation of the three orientations to happiness (OTH types). Individual differences in the three orientations to happiness and membership to OTH type were found to contribute to emotional, psychological and social well-being.

4.1 OTH Types

Applying a person-centred approach, our study supports the idea of a meaningful co-variation of the three orientations to happiness within individuals. Using a two-step cluster analytical procedure we identified four highly internally replicable OTH types, i.e. four groups of individuals with specific combination of three orientations to happiness, labelled full, pleasurable, meaningful, and empty life. The full life type included participants who reported to relatively frequently engage in activities that contribute to greater good, benefit others and serve a higher purpose (orientation to meaning), involve enjoyable, exciting and positive experiences (orientation to pleasure), and are engrossing, absorbing and challenging (orientation to engagement). The participants categorized in the pleasurable life type reported on achieving happiness primarily by seeking enjoyable experiences of positive emotions, while occasionally pursuing engagement and rarely seeking meaning. Participants classified in the meaningful life type were described by most pronounced perceptions of their lives as purposeful, significant, and understandable, while occasionally pursuing engagement and rather neglecting experiences of pleasure. The full, the pleasurable, and the meaningful life types were found to be approximately the same in size, including over a quarter of the participants each. The smallest cluster of participants was characterized by low expression of pleasure, meaning, and engagement orientations, thus leading an empty life as Peterson et al. (2005) named this pattern of orientations.

Based on previous theoretical and empirical reports (e.g., Peterson et al. 2005), the full and empty life types were rather expected. However, the presence and specific characteristics of other patterns of orientation to happiness have so far remained elusive. Our results suggested two additional types (pleasurable and meaningful) that present intuitively reasonable patterns of orientations to happiness and are consistent with traditional philosophical approaches to happiness (Ryan and Deci 2001). Both groups were characterized by moderate orientation to engagement, but quite the opposite patterns of meaning and pleasure orientations. Specifically, the pleasurable life type included individuals who seek happiness primarily through pleasurable activities, thus pursuing hedonic life, while they seem rather disinterested in meaningful activities. Unlike the pleasurable life type, the meaningful life type includes individuals, whose pursuit of happiness seems to rely mainly on eudaimonia, searching for meaning and self-fulfilment, and not pursuing pleasure. Thus, we found two OTH types which reflect two classical philosophical approaches to happiness—hedonia and eudaimonia. On the other hand, these two OTH types are similar in moderate levels of engagement: the individuals leading a meaningful and pleasurable life may be quite engaged in their frequent meaningful and pleasurable activities, respectively. These results are consistent with Waterman’s (1993) notion of flow as an “amalgam” of hedonic and eudemonic features. Therefore, it may not be surprising that we did not find a group of individuals with engagement as a dominant orientation.Footnote 1 It could be assumed, that the engagement orientation may refer to a specific quality of experiences—while meaning and pleasure indicate what individuals do, engagement denotes how they do something.

We have not found any other documented studies applying a person-centred approach to orientations of happiness, but Park et al. (2009) did use a clustering procedure to identify groups of nations with characteristic patterns of these orientations. Specifically, they classified aggregated OTH scores for 27 nations (mean OTH scores provided by members of each nation) and revealed three clusters, similar to those obtained in our study: one group of nations was characterized by relatively high endorsement of seeking pleasure and engagement, the second group by relatively high pursuing of engagement and meaning, and the third cluster by relatively low endorsement of all three ways of seeking happiness. Thus, a nations’ prototypical profile of orientations to happiness that would be comparable to full life did not emerge due to the possibility that such nations do not exist, are small/isolated and/or not populated by Internet users (data in the study was collected via internet site). Though nations that typically endorse full life may not exist, our study provides evidence for the presence of individuals pursuing all three pathways to happiness, at least with respect to their own subjective reports. Individuals pursuing full life may not be prevailing in a (Slovenian) population though the proportion of individuals characterized by full life OTH type was far from negligible (28 % of our sample).

4.2 Orientations to Happiness and Subjective Well-Being

Results of the present study indicate positive associations between all three orientations to happiness and all measures of subjective well-being. These results are in accordance with previous findings (e.g., Peterson et al. 2005; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2008), suggesting that each orientation is a possible way to achieve well-being. Results of the regression analyses performed offer additional support for the predictive validity of the three orientations to happiness for well-being.

Since previous investigations of interaction effects could not clarify satisfactorily the association of possible patterns of orientations to happiness with well-being measures, the person-centred approach was applied in our study. It enabled us to position groups of individuals with different patterns of orientations to happiness on the well-being continuum. Consistent with previous reports on interaction effects (e.g., Schueller and Seligman 2010; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2008), the full life type was the most strongly associated with all aspects of subjective well-being. On the other hand, neglecting all three paths of achieving happiness, i.e. leading an empty life, relates to relatively lowest emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Mean emotional, psychological, and social well-being of the individuals with pleasurable or meaningful life is generally lower in comparison to the individuals leading full life (with the exception of similar levels of social well-being in meaningful and full life types) and higher in comparison to the individuals with empty life.

However, a focal finding of the person-centred analyses performed concerns the distinction between pleasurable and meaningful life types, since they cannot be identified with dimension-centred approach. Specifically, individuals leading a pleasurable life reported on higher emotional well-being, similar psychological well-being and lower social well-being than the members of the meaningful life type.

Results of person- and dimension-centred approaches both indicated some inconsistencies with previous studies concerning the robustness of the three orientations to happiness as predictors of satisfaction with life and other well-being measures. Many studies (e.g., Chen et al. 2009; Kumano 2011; Park et al. 2009; Schueller and Seligman 2010; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2008) suggested that meaning and engagement contribute more to the well-being than the pleasure orientation. These findings seem to be in contrast to theoretical and empirical consideration of hedonia and eudaimonia, and might indicate low validity of the OTH scales (Henderson et al. 2013). Namely, in several studies (e.g., Anić 2012; Huta and Ryan 2010; Vittersø and Søholt 2011) hedonia emerged as a stronger predictor of life satisfaction than eudaimonia. Vittersø and Søholt (2011) suggest that pleasure orientation and satisfaction (e.g., with life) are elements of hedonic well-being and their main function is to reward goal achievement and mentally signalize the homeostatic stability of the body. Pleasure orientation could therefore be expected to have stronger associations with hedonic measures of well-being than meaning and engagement orientations. Our results are indeed consistent with this interpretation as pleasure was related to positive affect and life satisfaction to a similar or even higher degree than meaning. Likewise, results of person-centred approach revealed higher emotional well-being in members of pleasurable life type than members of meaningful life type.

Regarding psychological well-being, we found no evidence of this aspect of well-being to be related more to either pursuing pleasure or pursuing meaning, to leading either pleasurable or meaningful life. Psychological well-being, considered an indicator of eudaimonia, was expected to be more characteristic for the meaningful than for the pleasurable life type. It comprises aspects such as positive relationships, autonomy, meaning in life, personality growth, which are supposed to be more likely accessed through meaningful and not through pleasurable activities (Anić 2012; Henderson et al. 2013; Huta and Ryan 2010). Our results suggest that leading pleasurable life could also enable individuals to reach criteria for psychological well-being. However, pleasure orientation did not emerge as an important predictor of social-well-being. Supposedly, attaining social well-being is not done best by pursuing pleasure and choosing activities considering only one’s own pleasure and needs regardless of the pleasure and needs of the reference group.

Our study provided little evidence of the incremental predictive validity of OTH type membership above and beyond specific orientations to happiness, suggesting that OTH types contain little crucial information beyond that already offered by the linear combinations of the OTH dimensions alone. This is consistent with previous research on personality types (e.g., Asendorpf 2003; Zupančič et al. 2006), generally suggesting greater predictive value of personality dimensions over types. But the person-centred approach has some advantages in communication to the general public as well as to educators, counsellors, who can use this classification and design their interventions to heighten well-being of members of specific OTH types.

4.3 Limitations and Future Directions

Certain limitation of the present study should be mentioned, most notably the use of an internet sample. However, despite specific weaknesses (Smyth and Pearson 2008), internet studies represent an important data collection method for large and diverse samples with relatedly low costs (Birnbaum 2004). In addition, a German study (Ruch et al. 2010) provided evidence for psychometric equivalence of the pen-and-paper and internet versions of OTH questionnaire. We also believe that the internet approach did not result in a substantial sample bias as internet is used by 69 % of Slovenes, aged 10–74 years (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia 2011). This said, the sample of participants in this study was partial with respect to gender and age due to the availability of the participants and their willingness to participate. Nevertheless, the study included a large, age-heterogeneous sample of participants. A strong point of our study is also the use of a rigid methodology (Asendorpf et al. 2001), which enabled us to derive OTH types and examine their internal replicability. The OTH types obtained remain to be replicated with other samples and in other cultures. The associations between orientations to happiness and well-being might also be better understood by including measures of personality as orientations to happiness may be mediating or OTH types moderating the effects of personality on well-being. Moreover, the associations of the three orientations to happiness and their patterns with well-being measures do not necessarily imply causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to help clarify the direction of causality. Furthermore, people who self-reportedly pursue a certain path to happiness or are a member of a certain OTH type are presumed to engage in respective activities (e.g., people high on orientation to pleasure should do a lot of pleasurable things). Thus, the question whether the level of orientations to happiness and the membership to OTH types manifest in people’s actual daily activities awaits future empirical inquiries.

5 Conclusion

Results presented provide support for the hypothesis that orientations to happiness as measured with OTH are organized into characteristic patterns within individuals and these patterns have predictive value for emotional, psychological, and social well-being. These patterns or types are in accordance with the theory and intuitive expectations: Full life and empty life types include individuals with high and low expression of all three orientations, respectively. The other two OTH types obtained were both described by moderate orientation to engagement, but differed characteristically in levels of meaning and pleasure orientations, reflecting traditional philosophical distinction between hedonia and eudaimonia. These results might help elucidate the enduring issue of outlining engagement or flow as either a third pathway to happiness or as a manner of more or less engaged participation in hedonic and eudaimonic activities. The person-centred approach offers an additional perspective suggesting that engagement cannot be present without pursuing also pleasure or/and meaning.

Concerning the relation between orientations to happiness and subjective well-being, our results do not indicate meaning and engagement to be more robust predictors of well-being than the pleasure orientation, as documented previously (Henderson et al. 2013). Consistent with theoretic postulations (e.g., Anić 2012; Henderson et al. 2013; Huta and Ryan 2010), our results suggest that pursuing pleasure is somewhat more important for individual’s emotional well-being than searching for meaning.

Although OTH type membership did not add to the prediction of well-being above the three orientations, the use of a person-centred approach yielded some valuable information regarding the above mentioned theoretical issues, as well as possible psychological interventions. Based on our findings, positive intervention would be especially beneficiary for members of the empty life type. Furthermore, the emotional well-being of individuals leading a meaningful life could be promoted by more frequent experiences of positive emotions through joyful and pleasurable activities, while individuals leading pleasurable life might gain higher subjective well-being by participating more frequently in meaningful activities concerning other people or higher purpose. Promoting solely higher engagement irrespective of low hedonic or eudaimonic orientation is suggested to be less effective in experiencing subjective well-being.

Notes

A pattern with engagement as a dominant orientation did not emerge even when solutions with more clusters were considered (e.g., in a five-cluster solution an additional cluster with high engagement and pleasure, and average meaning emerged).

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1985). Patterns of attachment. Clinical Psychologist, 38, 27–29.

Anić, P. (2012). How to find happiness: Life goals and free time activities (Doctoral dissertation). Ljubljana, Slovenia: University of Ljubljana.

Asendorpf, J. B. (2003). Head-to-head comparison of the predictive validity of personality types and dimensions. European Journal of Personality, 17, 327–346.

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169–198.

Avsec, A., & Kavčič, T. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Slovene version of the orientations to Happiness Questionnaire. Horizons of Psychology, 21(1), 7–18.

Birnbaum, M. H. (2004). Human research and data collection via the Internet. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 803–832.

Catalino, L. I., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). Tuesdays in the lives of flourishers: The role of positive emotional reactivity in optimal mental health. Emotion, 11, 938–950.

Chen, G.-H. (2010). Validating the Orientations to Happiness Scale in a Chinese sample of university students. Social Indicators Research, 99, 431–442.

Chen, L. H., Tsai, Y.-M., & Chen, M.-Y. (2009). Psychometric analysis of the orientations to happiness questionnaire in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Social Indicator Research, 98, 239–249.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9, 361–368.

Costa, P. T, Jr, Herbst, J. H., McCrae, R. R., Samuels, J., & Ozer, D. J. (2002). The replicability of three personality types. European Journal of Personality, 16, 73–87.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow, the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19, 313–332.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13, 172–175.

Hart, D., Atkins, R., & Fegley, S. (2003). Personality and development in childhood: A person-centered approach. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 68(1), 1–109.

Henderson, L. W., Knight, T., & Richardson, B. (2013). The hedonic and eudaimonic validity of the Orientations to Happiness Scale. Social Indicators Research,. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0264-4.

Hirschi, A. (2011). Effects of orientations to happiness on vocational identity achievement. The Career Development Quarterly, 59, 367–378.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Odessa, FL, US: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Huta, W., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 735–762.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 121–140.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental health and/or mental illness? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). Mental Health Continuum-Long Form. In J. Magyae-Moe (Ed.), Therapist’s guide to positive psychological interventions (pp. 30–33). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Kumano, M. (2011). Orientations to happiness in Japanese people: Pleasure, meaning, and engagement. Shinrigaku Kenkyu, 81(6), 619–624.

Mervielde, I., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2000). Variable-centred and person-centred approaches to childhood personality. In S. E. Hampson (Ed.), Advances in personality psychology (pp. 37–76). Hove: Psychology Press Ltd.

Mroczek, D. K., & Kolarz, C. M. (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1333–1349.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Ruch, W. (2009). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction in twenty-seven nation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 273–279.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41.

Robitschek, C., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). Keyes’s model of mental health with personal growth initiative as a parsimonious predictor. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 321–329.

Ruch, W., Harzer, C., Proyer, T. R., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2010). Ways to happiness in German-speaking countries: The adaptation of the German version of the orientations to happiness questionnaire in paper-pencil and internet samples. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 227–234.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39.

Schueller, S. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2010). Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 253–263.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York: The Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., Parks, A. C., & Steen, T. (2005). A balanced psychology and a full life. In F. Huppert, B. Keverne, & N. Baylis (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 275–283). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smyth, J. D., & Pearson, J. E. (2008). Internet survey methods: A review of strengths, weaknesses, and innovations. In M. Das, P. Ester, & L. Kaczmirek (Eds.), Social and behavioral research and the internet advances in applied methods and research strategies (pp. 14–36). New York, London: Rutledge.

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2011). The use of communication technology in households and individuals, Slovenia, 2011, final data. Retrieved December 15, 2012 from http://www.stat.si/novica_prikazi.aspx?ID=4240.

Vella-Brodrick, D. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2008). Three ways to be happy: Pleasure, engagement, and meaning—findings from Australian and US samples. Social Indicators Research, 90, 165–179.

Vittersø, J., & Søholt, Y. (2011). Life satisfaction goes with pleasure and personal growth goes with interest: Further arguments for separating hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 326–335.

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678–691.

Zupančič, M., Podlesek, A., & Kavčič, T. (2006). Personality types as derived from parental reports on 3-year-old. European Journal of Personality, 20, 285–303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kavčič, T., Avsec, A. Happiness and Pathways to Reach It: Dimension-Centred Versus Person-Centred Approach. Soc Indic Res 118, 141–156 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0411-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0411-y