Abstract

Injection drug use is the primary driver of the HIV epidemic in Iran. We characterized people who inject drugs (PWID) living in Iran who had never received opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and examined barriers to OAT uptake. We recruited 2684 PWID with a history of drug injection in the previous 12 months using a respondent-driven sampling approach from 11 geographically dispersed cities in Iran. The primary outcome was no lifetime uptake history of OAT medications. The lifetime prevalence of no history of OAT uptake among PWID was 31.3%, with significant heterogeneities across different cities. In the multivariable analysis, younger age, high school education or above, no prior incarceration history, and shorter length of injecting career were significantly and positively associated with no history of OAT uptake. Individual-level barriers, financial barriers, and system-level barriers were the main barriers to receiving OAT. PWID continue to face preventable barriers to accessing OAT, which calls for revisiting the OAT provision in Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In several countries, including Iran, injection drug use continues to be the main driver of the HIV epidemic (Van Santen et al., 2021). In Iran, where about 340,000 people who inject drugs (PWID) live (Rastegari et al., 2022), the pooled prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) among PWID has been estimated to be 9.7% and 46.5%, respectively (Rahimi et al., 2020; Rajabi et al., 2021). Opioids are the most prevalent drugs in Iran among the general population (Mohebbi et al., 2019) and PWID (Nakhaeizadeh et al., 2020). Opium is the primary opioid of use in Iran, followed by shireh (i.e., refined opium), non-prescribed methadone, and heroin/heroin-kerack (i.e., a more potent form of street heroin that does not have any cocaine but contains heroin, codeine, morphine, and caffeine) (Amin-Esmaeili et al., 2016; Farhoudian et al., 2014).

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) is regarded as an essential medication by the World Health Organization due to its crucial role in reducing heroin injection, crimes rates, and injection-related morbidity and mortality (Gisev et al., 2019). Moreover, accessing appropriately dosed OAT services among PWID has been associated with several positive mental and physical health outcomes, such as lower HIV and HCV acquisition risk, increased antiretroviral therapy initiation among people living with HIV, increased HIV testing, reduced fatal and non-fatal overdose, improved day-to-day functioning, reduced withdrawal symptoms, improved depressive symptoms, and improved quality of life (Bahji et al., 2019; Ferraro et al., 2021; Mlunde et al., 2016; Moazen-Zadeh et al., 2021; Nielsen et al., 2016). In Iran, methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) programs were introduced in 2002 and the national methadone treatment protocol and regulations for the scaling up OAT service provision were released in 2004 (Ekhtiari et al., 2020). Iran has the most extensive OAT program in the Eastern Mediterranean region and over 7200 clinics (97% in the private sector) provide these services (Ekhtiari et al., 2020). Given the favourable health and addiction treatment-related outcomes associated with accessing OAT services (Nielsen et al., 2016), characterizing OAT access among PWID is essential for informing Iran’s harm reduction policies and planning.

While previous studies have tried to characterize people who have accessed OAT in Iran (Nakhaeizadeh et al., 2020), treatment uptake is suboptimal, and our understanding of PWID who are disconnected from treatment services and have never received such life-saving services is minimal. Moreover, little is known about the barriers to accessing OAT among PWID who have never been linked to substance use care and treatment. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to (i) measure the lifetime prevalence of no history of OAT uptake among PWID in Iran and characterize this subgroup of PWID and (ii) identify the primary barriers to OAT uptake among PWID who have never been connected to OAT services. We hypothesize that access to OAT is inequitable across the country and certain socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics contribute to PWID’s reduced access to OAT. The findings of this study could shed light on the provincial disparities in accessing OAT and could help remove the existing barriers to using these services in Iran.

Methods

Setting and Sampling

Data were obtained from the recent nationwide integrated bio-behavioural surveillance survey (IBBSS) of PWID in Iran (July 2019 to March 2020). Details of the methodology are previously described (Khezri et al., 2021, 2022).

In brief, data were collected using a structured and standard behavioural questionnaire via face-to-face interviews in 11 major cities. Participants were recruited using the respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method (Heckathorn, 1997). Participants were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, had at least one injection drug use practice in the last 12 months (assessed by self-report), had a valid coupon (except initial recruits), and provided verbal consent. Initial recruitment was performed using a non-random selection of well-networked participants called “seeds.” Every seed was then provided with three referral coupons and trained to recruit up to three peers. Peers who had received a referral coupon had 3 weeks to participate before the coupon expired (Faghihi et al., 2022). This process was continued using the referral coupons until the intended sample size was reached.

Eligible participants completed an interviewer-administered validated risk assessment questionnaire. This publicly available standardized questionnaire was developed based on recent IBBSS across various settings, including the USA, eight countries in Africa, Brazil, China, and the Caribbean (Global Strategic Information, 2014). Using a standardized questionnaire allows for cross-country comparisons among PWID and facilitates data collection on UNAIDS global AIDS monitoring indicators among PWID (UNAIDS, 2022). Following forward and backward translation of the questionnaire by two independent bilingual translators, it was reviewed and revised based on feedback from a questionnaire working group, including local HIV and substance use experts at Iran’s Ministry of Health and key informants from the local community of PWID. The questionnaire was then pilot-tested with a small group of PWID to ensure clarity, relevance, and accessibility. Content validity was assessed by an expert panel using the item content validity index and values < 0.78 were removed. Internal reliability was assessed by measuring the Cronbach α coefficient and values > 0.7 were considered to have adequate internal consistency (Tsang et al., 2017). The questionnaire took about an hour to complete and included several sections, such as PWID’s socio-demographic information, injection and non-injection substance use practices, sexual behaviours, substance use treatment history, HIV-related risks, mental health, and harm reduction service utilization. In addition, participants who consented to provide biological samples also completed a rapid test to assess their HIV (SD-Bioline, South Korea) and HCV serostatus. Those with reactive HIV tests completed a confirmatory test with Unigold HIV rapid test and were referred to voluntary counselling and testing services. Every participant received two United States Dollars (USD) as an incentive for completing the survey and HIV and HCV testing, and one USD for each referred peer.

Outcome Variable

Participants were asked whether they had ever received prescribed OAT medications (i.e., methadone, buprenorphine, or opium tincture maintenance treatment) at any point in life. Responses were coded as no vs. yes (reference group). To explore reasons for facing barriers in accessing OAT, participants were asked whether they had ever wanted to receive any OAT services but could not. Response options included “no, I have never wanted to seek OAT,” “yes, I wanted to receive OAT, and I received it,” and “yes, I wanted to, but I could not.” People who reported being unable to receive OAT were further asked “what were the reasons you could not receive the treatment?” with the following response options: the program was not free; there were no empty spots for new recruits to the treatment program; having a hard time and not feeling like getting treatment; could not afford the fees; no treatment program was available near my residence; mental health disorders; program’s service hours interfered with my work hours; not having an identification card which is required for signing up in the program; misbehaviours of staff and healthcare providers; and an opened-ended option for “other” responses. Participants could choose multiple options.

Independent Variables

Independent variables of interest were informed by Rhodes’ risk environment framework (Rhodes, 2009). Traditionally, research on substance use-related harms has primarily focused on individual-level risks and behaviour change. A growing body of evidence however, has highlighted the limitations of such conceptual frameworks (e.g., health belief model) that underscore individual-level decision-making interventions as a remedy to reducing substance use-related harms and adverse health outcomes (Rhodes, 2002; Strathdee et al., 2010). Rhodes’ framework takes on a more contextual approach towards identifying factors that affect PWUD’s health (Rhodes, 2002, 2009). Through the lens of risk environment framework applied in this research, individual-level behaviours and outcomes (e.g., access to substance use treatment) are consequences or products of the interaction of individual-level factors (e.g., length of injecting career) with several influences within the economic (e.g., access to adequate regular income), physical (e.g., homelessness), political (e.g., drug laws and regulations), and social (e.g., relationship status) environments. Informed by this lens, the variables included in our analysis included socio-demographic and behavioural variables, including gender (man or woman), education (< high school, or ≥ high school), marital status (married or single), monthly income (USD 100 + or \(\le\) USD 100), homelessness history (yes or no), incarceration history (yes or no), length of injecting career (< 1, or 1–5 years, or > 5 years), early (i.e., < 18 years old) injection initiation (yes or no), and age at interview (continuous, per 1 year older).

Statistical Analysis

We reported descriptive statistics and frequencies along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for no history of OAT uptake and independent variables. To assess the correlates of no history of OAT uptake, bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models were constructed. Variables with a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were entered into the multivariable model, and the final model was selected via a backward elimination approach based on the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC). Crude and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) along with 95% CI were reported. As unweighted regression models have been proposed to be more accurate, have more coverage, and provide more robust estimates than RDS-weighted models (Avery et al., 2019), we relied on an unweighted regression modelling approach in line with an increasing body of evidence (Friedman et al., 2021; Saleem et al., 2021). As most substance use-related variables in the questionnaire had measured recent use/injection practices, they were not included in the regression analyses to avoid temporality bias. In a sensitivity analysis, we also reported RDS-adjusted estimates for the primary outcome and in subgroups of PWID.

We also categorized barriers to accessing OAT into three main themes. For the “other” response option, free texts were thematically summarized and, where consistent with the main themes, were included in the main themes. Responses that were not clarified in the free text or consistent with the main themes were reported as “other.” As the study was performed in different cities, we considered each city as a cluster and adjusted the cluster effects using Stata’s survey package. Data management and data analysis procedures were performed using Stata 14.2. RDS-adjusted estimates were calculated using RDS analyst 1.8–6.

Results

Participant Characteristics

We analysed data for 2684 PWID with a lifetime history of opioid use for non-medical purposes (Table 1). Among them, 2564 (96.6%) were men, 1824 (69.1%) had < high school level of education, 655 (25.6%) were married, 1731 (66.1%) had ever been incarcerated, 1489 (56.6%) had ever been homeless, 213 (8.4%) had injected for ≤ 1 year, and 561 (22.0%) had injected for 2–5 years. Moreover, 96% self-reported injecting opioids in the past 3 months. RDS-weighted and RDS-unweighted prevalence of socio-demographic variables are presented in Supplement 1.

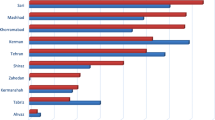

Overall, the lifetime prevalence of no history of OAT uptake was 31.3% (95% CI: 29.5, 33.1). However, it varied greatly across the studied cities, ranging from 7.4% in East Azerbaijan to 63.1% in Lorestan (Fig. 1). In the bivariable analysis (Table 1), those who had never accessed OAT were significantly younger (mean age: 38.5 vs. 41.0, p-value < 0.001), had high school education and above (36.9% vs. 28.8%, p-value < 0.001), had never been homeless (31.6% vs. 29.2%, p-value = 0.190), had never been incarcerated (38.4% vs. 26.1%, p-value < 0.001), and had a shorter injecting career (36.5% vs. 26.5%, p-value < 0.001). In the multivariable analysis (Table 2), the odds of never having received OAT were significantly and positively associated with lower age (aOR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.97, 0.99), high school education or above (aOR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.67), no history of incarceration (aOR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.23, 1.79), and shorter injecting career (aOR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.97).

Approximately 2637 participants answered the question “have you ever wanted to receive any OAT services but were unable to?” 1352 (51.3%) of whom reported “yes, I wanted to, but I could not.” People who reported being unable to receive OAT described the main underlying reasons, summarized thematically in Table 3. Individual-level barriers, 914 (66.2%); financial barriers, 257 (18.6%); and system-related barriers, 197 (14.3%) were the main three barriers to accessing OAT. Overall, 46 people reported “other” reasons, of which 34 people provided the free text, which was classified in the main themes, and 12 (0.9%) participants reported the “other” response but did not specify further.

Discussion

We found that one-third of PWID in Iran had never received OAT during their lifetime. While Iran benefits from the highest OAT coverage in the Eastern Mediterranean region, where less than ten countries provide OAT services (Roshanfekr et al., 2013), the observed gap and disparities in accessing OAT across the country are concerning. Younger people, those who had higher education, had never been incarcerated, and had a shorter injection career length had higher odds of no history of OAT uptake. About two-thirds of participants reported individual-level barriers, one-fifth reported financial issues, and more than one-tenth of participants reported system-related barriers in accessing OAT services.

Younger PWID were more likely to have never received OAT. This finding is consistent with an international body of evidence indicating several gaps in accessing OAT among young people (Pilarinos et al., 2021) and calls for revisiting and revising Iran’s national clinical OAT guidelines to further emphasize the need to improve OAT uptake for young PWID. While reduced access to OAT among young people is partly related to how substance use treatment is provided (Pilarinos et al., 2021), it could also be due to their lower perceived risks of opioid use and higher levels of perceived (i.e., current or previous experiences of healthcare-related discrimination) or anticipated stigma (i.e., expecting healthcare-related discrimination in the future) towards receiving OAT (Earnshaw et al., 2019; Hadland et al., 2018). Substance use stigma reduction interventions aimed at tackling stigma at the individual (e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy), societal (e.g., public awareness campaigns about OAT services), and structural levels (e.g., targeted educational programs for healthcare providers and law enforcement) could help lead to higher retention and better health outcomes among PWID and reduce interpersonal and structural stigma towards OAT uptake among them (Livingston et al., 2012; Woo et al., 2017).

No history of incarceration was associated with higher odds of no OAT uptake. This could be due to the provision of harm reduction services, including MMT inside prisons in Iran, which increases the odds of PWID’s access to OAT if incarcerated (Nakhaeizadeh et al., 2020). Ensuring that such services inside prisons are scaled up and receive continued support is essential, given their well-established effect on reduced injection- and non-injection-related harms as well as increased linkage to care both inside and outside prisons (Marsden et al., 2017; Roshanfekr et al., 2013; Saberi Zafarghandi et al., 2021). We also noted that a lower duration of injecting career was associated with higher odds of no OAT uptake. Previous studies suggest that treatment-seeking practices are usually overlooked and postponed until serious complications emerge (Topp et al., 2008) and highlight the importance of providing low-threshold and accessible OAT services to facilitate access among people who are early injectors or are experimenting with injection drug use (Montain et al., 2016).

Less than 4% of PWID in our study self-identified as women. Consistent with other parts of the world (El-Bassel & Strathdee, 2015), a minority of women—who are often socio-economically marginalized—inject drugs in Iran (Tavakoli et al., 2021). The most commonly used drug in Iran continues to be opium (4271/100,000 people among men vs. 766/100,000 among women) and the overall prevalence of substance use (injection or non-injection) has been estimated to be 5.23 times higher among men than women (Rastegari et al., 2022). In Iran, an estimated ~ 16,000 women inject drugs (Nikfarjam et al., 2016) and ~ 3% of PWID are women (Dolan et al., 2011). While the low representation of women in our study could be reflective of the low prevalence of injection drug use among women, it could also be due to the high levels of stigma associated with injection drug use among women (e.g., gender-specific cultural expectations) and potential adverse consequences for them (e.g., possible loss of their children’s custody due to severe substance use disorders) in the conservative and traditional socio-cultural context of Iran (Dehghan et al., 2020; Sattler et al., 2021; Zolala et al., 2016).

More than half of the participants reported facing barriers to accessing OAT. PWID reported an array of individual, financial, and system-level barriers to accessing OAT services that could be addressed through several scalable interventions. First, as personal struggles and challenges were frequently reported to complicate seeking OAT, existing services need to ensure that they are compatible with the long-term nature of recovery and continue supporting PWID despite their potentially repeated cycles of relapse (Wegman et al., 2017). It is also essential to ensure that existing OAT services are flexible and that a “one size fits all” approach is subject to limited success and would not work for all PWID (Karamouzian et al., 2022). Second, the financial costs associated with accessing OAT care have been repeatedly reported as a significant barrier and need to be dealt with (Khazaee-Pool et al., 2018). OAT services in Iran are provided in public and private clinics with varying costs across different settings. While accurate estimates of the average cost of treatment in private settings are unclear, MMT would cost an average of ~ $20–$30 per client/month in 2018 in public clinics. Notably, OAT services are also available at a lower cost in harm reduction drop-in centres which provide low-threshold services, but seeking services within those settings is often highly stigmatized (Hesam et al., 2014). Moreover, health insurance for substance use treatment only covers clients with valid identification documents and merely a portion of monthly methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment packages (Momtazi et al., 2015). Lastly, system-level barriers could be addressed by cost-efficient interventions, such as revising the operational hours of OAT services, increasing accessibility of services in remote and rural areas, promoting gender-sensitive addiction care and treatment, and educating healthcare staff to ensure PWID do not face external stigma when seeking care (Dolan et al., 2011; Karamouzian et al., 2022; Shirley-Beavan et al., 2020). Future research in Iran should also investigate the barriers and facilitators to accessing OAT among PWID from the staff’s perspectives and ensure any programs aimed at improving these services are adequately informed by service providers’ input.

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the data was collected via self-reports which may be subject to recall and reporting biases. We tried to reduce probable biases by training and employing local interviewers. Second, this cross-sectional study measured both exposure and outcome at the same section of time; therefore, causality cannot be inferred. Lastly, men who inject drugs were overrepresented in the survey, limiting our findings’ generalizability to women who inject drugs in Iran.

Conclusions

In summary, one-third of PWID had no history of OAT uptake. Although the increasing number of OAT services in Iran is encouraging, there is significant disparity across the country regarding accessing OAT. Moreover, several preventable barriers continue to undermine PWID’s access to OAT and need to be addressed through revisiting and revising OAT-related policies and interventions.

Data Availability

Data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author as well as the approval of Iran’s Ministry of Health.

References

Amin-Esmaeili, M., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., Sharifi, V., Hajebi, A., Radgoodarzi, R., Mojtabai, R., Hefazi, M., & Motevalian, A. (2016). Epidemiology of illicit drug use disorders in Iran: Prevalence, correlates, comorbidity and service utilization results from the Iranian Mental Health Survey. Addiction, 111(10), 1836–1847. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13453

Avery, L., Rotondi, N., McKnight, C., Firestone, M., Smylie, J., & Rotondi, M. (2019). Unweighted regression models perform better than weighted regression techniques for respondent-driven sampling data: Results from a simulation study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0842-5

Bahji, A., Cheng, B., Gray, S., & Stuart, H. (2019). Reduction in mortality risk with opioid agonist therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 140(4), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13088

Dehghan, M., Shokoohi, M., Mokhtarabadi, S., Tavakoli, F., Iranpour, A., Rad, A. A. R., Nasiri, N., Karamouzian, M., & Sharifi, H. (2020). HIV-related knowledge and stigma among the general population in the southeast of Iran. Shiraz E Medical Journal, 21(7), e96311. https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.96311

Dolan, K., Salimi, S., Nassirimanesh, B., Mohsenifar, S., Allsop, D., & Mokri, A. (2011). Characteristics of Iranian women seeking drug treatment. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(11), 1687–1691. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2694

Earnshaw, V. A., Bogart, L. M., Menino, D. D., Kelly, J. F., Chaudoir, S. R., Reed, N. M., & Levy, S. (2019). Disclosure, stigma, and social support among young people receiving treatment for substance use disorders and their caregivers: A qualitative analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(6), 1535–1549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9930-8

Ekhtiari H, N. A., Farhoudian A, Radfar SR, Hajebi A, Sefatian S, Zare-Bidoky M, Razaghi EM, Mokri A, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Rawson R. (2020). The evolution of addiction treatment and harm reduction programs in Iran: A chaotic response or a synergistic diversity. Addiction, 115(7), 1395–1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14905.

El-Bassel, N., & Strathdee, S. A. (2015). Women who use or inject drugs: An action agenda for women-specific, multilevel and combination HIV prevention and research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 69(Suppl 2), S182. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000628.

Faghihi, S. H., Ghalekhani, N., Kazerooni, P. A., & Nasirian, M. (2022). Size estimation of people who inject drugs and their geographical distribution in dogonbadan, Iran, during 2018: A mapping method. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 1246–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00439-1

Farhoudian, A., Sadeghi, M., Khoddami Vishteh, H. R., Moazen, B., Fekri, M., & Rahimi Movaghar, A. (2014). Component analysis of Iranian crack; a newly abused narcotic substance in Iran. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research, 13(1), 337–344. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24734089/.

Ferraro, C. F., Stewart, D. E., Grebely, J., Tran, L. T., Zhou, S., Puca, C., Hajarizadeh, B., Larney, S., Santo, T., Jr., & Higgins, J. P. (2021). Association between opioid agonist therapy use and HIV testing uptake among people who have recently injected drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 116(7), 1664–1676. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15316

Friedman, J., Syvertsen, J. L., Bourgois, P., Bui, A., Beletsky, L., & Pollini, R. (2021). Intersectional structural vulnerability to abusive policing among people who inject drugs: A mixed methods assessment in California’s central Valley. International Journal of Drug Policy, 87, 102981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102981

Gisev, N., Bharat, C., Larney, S., Dobbins, T., Weatherburn, D., Hickman, M., Farrell, M., & Degenhardt, L. (2019). The effect of entry and retention in opioid agonist treatment on contact with the criminal justice system among opioid-dependent people: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 4(7), e334–e342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30060-X

Hadland, S. E., Park, T. W., & Bagley, S. M. (2018). Stigma associated with medication treatment for young adults with opioid use disorder: A case series. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0116-2

Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174–199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941

Hesam, S., Honarvar, N., & Vahdat, S. (2014). The analysis of cost-effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment for preventing HIV infection in drug-injection users (a case study: the selected withdrawal centers under the supervision of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences). Journal of Health Accounting, 3(3), 18–39. https://doi.org/10.30476/jha.2014.16991.

Global Strategic Information. (2014). Toolbox for conducting integrated HIV bio-behavioral surveillance (IBBS) in key populations: PWID questionnaire. Retrieved November 30, 2022 from https://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/sites/globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/files/ibbs-intro.pdf.

Karamouzian, M., Pilarinos, A., Hayashi, K., Buxton, J. A., & Kerr, T. (2022). Latent patterns of polysubstance use among people who use opioids: A systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102, 103584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103584

Khazaee-Pool, M., Moeeni, M., Ponnet, K., Fallahi, A., Jahangiri, L., & Pashaei, T. (2018). Perceived barriers to methadone maintenance treatment among Iranian opioid users. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0787-z

Khezri, M., Karamouzian, M., Sharifi, H., Ghalekhani, N., Tavakoli, F., Mehmandoost, S., Mehrabi, F., Pedarzadeh, M., Nejat, M., & Noroozi, A. (2021). Willingness to utilize supervised injection facilities among people who inject drugs in Iran: Findings from 2020 national HIV bio-behavioral surveillance survey. International Journal of Drug Policy, 97, 103355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103355

Khezri, M., Shokoohi, M., Mirzazadeh, A., Tavakoli, F., Ghalekhani, N., Mousavian, G., Mehmandoost, S., Kazerooni, P. A., Haghdoost, A. A., Karamouzian, M., & Sharifi, H. (2022). HIV prevalence and related behaviors among people who inject drugs in Iran from 2010 to 2020. AIDS and Behavior, 26, 2831–2843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03627-3

Livingston, J. D., Milne, T., Fang, M. L., & Amari, E. (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

Marsden, J., Stillwell, G., Jones, H., Cooper, A., Eastwood, B., Farrell, M., Lowden, T., Maddalena, N., Metcalfe, C., & Shaw, J. (2017). Does exposure to opioid substitution treatment in prison reduce the risk of death after release? A national prospective observational study in England. Addiction, 112(8), 1408–1418. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13779

Mlunde, L. B., Sunguya, B. F., Mbwambo, J. K. K., Ubuguyu, O. S., Yasuoka, J., & Jimba, M. (2016). Association of opioid agonist therapy with the initiation of antiretroviral therapy-a systematic review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 46, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.022

Moazen-Zadeh, E., Ziafat, K., Yazdani, K., Kamel, M. M., Wong, J. S. H., Modabbernia, A., Blanken, P., Verthein, U., Schütz, C. G., Jang, K., Akhondzadeh, S., & Krausz, R. M. (2021). Impact of opioid agonist treatment on mental health in patients with opioid use disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 47(3), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2021.1887202

Mohebbi, E., Haghdoost, A. A., Noroozi, A., Vardanjani, H. M., Hajebi, A., Nikbakht, R., Mehrabi, M., Kermani, A. J., Salemianpour, M., & Baneshi, M. R. (2019). Awareness and attitude towards opioid and stimulant use and lifetime prevalence of the drugs: A study in 5 large cities of Iran. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(4), 222. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.128.

Momtazi, S., Noroozi, A., & Rawson, R. (2015). An overview of Iran drug treatment and harm reduction programs. Textbook of addiction treatment: International perspectives. Springer, 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-5322-9_25.

Montain, J., Ti, L., Hayashi, K., Nguyen, P., Wood, E., & Kerr, T. (2016). Impact of length of injecting career on HIV incidence among people who inject drugs. Addictive Behavior, 58, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.020

Nakhaeizadeh, M., Abdolahinia, Z., Sharifi, H., Mirzazadeh, A., Haghdoost, A. A., Shokoohi, M., Baral, S., Karamouzian, M., & Shahesmaeili, A. (2020). Opioid agonist therapy uptake among people who inject drugs: The findings of two consecutive bio-behavioral surveillance surveys in Iran. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00392-1

Nielsen, S., Larance, B., Degenhardt, L., Gowing, L., Kehler, C., & Lintzeris, N. (2016). Opioid agonist treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependent people. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5), Cd011117. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011117.pub2.

Nikfarjam, A., Shokoohi, M., Shahesmaeili, A., Haghdoost, A. A., Baneshi, M. R., Haji-Maghsoudi, S., Rastegari, A., Nasehi, A. A., Memaryan, N., & Tarjoman, T. (2016). National population size estimation of illicit drug users through the network scale-up method in 2013 in Iran. International Journal of Drug Policy, 31, 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.013

Pilarinos, A., Bromberg, D. J., & Karamouzian, M. (2021). Access to medications for opioid use disorder and associated factors among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(3), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4606

Rahimi, Y., Gholami, J., Amin-Esmaeili, M., Fotouhi, A., Rafiemanesh, H., Shadloo, B., & Rahimi-Movaghar, A. (2020). HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs (PWID) and related factors in Iran: A systematic review, meta-analysis and trend analysis. Addiction, 115(4), 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14853

Rajabi, A., Sharafi, H., & Alavian, S. M. (2021). Harm reduction program and hepatitis C prevalence in people who inject drugs (PWID) in Iran: An updated systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00441-9

Rastegari, A., Baneshi, M. R., Hajebi, A., Haghdoost, A. A., Sharifi, H., Noroozi, A., Karamouzian, M., Shokoohi, M., Mirzazadeh, A., & Haji Maghsoudi, S. (2022). Population size estimation of people using illicit drugs and alcohol in Iran (2015–2016). International journal of health policy and management. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6578.

Rhodes, T. (2002). The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5

Rhodes, T. (2009). Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20(3):193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003.

Roshanfekr, P., Farnia, M., & Dejman, M. (2013). The effectiveness of harm reduction programs in seven prisons of Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 42(12), 1430–1437. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441940/.

Saberi Zafarghandi, M. B., Eshrati, S., Arezoomandan, R., Farnia, M., Mohammadi, H., Vahed, N., Javaheri, A., Amini, M., & Heidari, S. (2021). Review, documentation, assessment of treatment, and harm reduction programs of substance use disorder in Iranian Prisons. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 27(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.32598/ijpcp.27.1.3324.1.

Saleem, H. T., Likindikoki, S., Nonyane, B. A., Nkya, I. H., Zhang, L., Mbwambo, J., & Latkin, C. (2021). Correlates of non-fatal, opioid overdose among women who use opioids in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108419

Sattler, S., Zolala, F., Baneshi, M. R., Ghasemi, J., & Amirzadeh Googhari, S. (2021). Public stigma toward female and male opium and heroin users. An experimental test of attribution theory and the familiarity hypothesis. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 652876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.652876.

Shirley-Beavan, S., Roig, A., Burke-Shyne, N., Daniels, C., & Csak, R. (2020). Women and barriers to harm reduction services: A literature review and initial findings from a qualitative study in Barcelona, Spain. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00429-5

Strathdee, S. A., Hallett, T. B., Bobrova, N., Rhodes, T., Booth, R., Abdool, R., & Hankins, C. A. (2010). HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: The past, present, and future. The Lancet, 376(9737), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X

Tavakoli, F., Khezri, M., Tam, M., Bazrafshan, A., Sharifi, H., & Shokoohi, M. (2021). Injection and non-injection drug use among female sex workers in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108655

Topp, L., Iversen, J., Conroy, A., Salmon, A. M., Maher, L., & NSPs, C. o. A. (2008). Prevalence and predictors of injecting-related injury and disease among clients of Australia's needle and syringe programs. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 32(1), 34-37.

Tsang, S., Royse, C., & Terkawi, A. (2017). Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 11(5), 80. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.sja_203_17

UNAIDS. (2022). Global AIDS Monitoring 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022 from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2022/global-aids-monitoring-guidelines.

Van Santen, D. K., Boyd, A., Matser, A., Maher, L., Hickman, M., Lodi, S., & Prins, M. (2021). The effect of needle and syringe program and opioid agonist therapy on the risk of HIV, hepatitis B and C virus infection for people who inject drugs in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Findings from an emulated target trial. Addiction, 116(11), 3115–3126. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15503

Wegman, M. P., Altice, F. L., Kaur, S., Rajandaran, V., Osornprasop, S., Wilson, D., Wilson, D. P., & Kamarulzaman, A. (2017). Relapse to opioid use in opioid-dependent individuals released from compulsory drug detention centres compared with those from voluntary methadone treatment centres in Malaysia: A two-arm, prospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e198–e207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30303-5

Woo, J., Bhalerao, A., Bawor, M., Bhatt, M., Dennis, B., Mouravska, N., Zielinski, L., & Samaan, Z. (2017). “Don’t judge a book by its cover”: A qualitative study of methadone patients’ experiences of stigma. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221816685

Zolala, F., Mahdavian, M., Haghdoost, A. A., & Karamouzian, M. (2016). Pathways to addiction: A gender-based study on drug use in a triangular clinic and drop-in center, Kerman, Iran. International Journal of High-Risk Behaviors & Addiction, 5(2), e22320. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.22320

Acknowledgements

For this paper, we would like to acknowledge the scientific input received from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH123256. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute for Medical Research Development (grant number 973382), Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Iran. MK is supported by a Banting postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Before starting the interview, participants were briefed about the study’s objectives and procedures. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehrabi, F., Mehmandoost, S., Mirzazadeh, A. et al. Characterizing People Who Inject Drugs with no History of Opioid Agonist Therapy Uptake in Iran: Results from a National Bio-behavioural Surveillance Survey in 2020. Int J Ment Health Addiction 22, 2378–2390 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00992-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00992-x