Abstract

Background

The internet has an increasing role in both patient and physician education. While several recent studies critically appraised the quality and accuracy of web-based written information available to patients, no studies have evaluated such parameters for open-access video content designed for provider use.

Questions/Purposes

The primary goal of the study was to determine the accuracy of internet-based instructional videos featuring the shoulder physical examination.

Methods

An assessment of quality and accuracy of said video content was performed using the basic shoulder examination as a surrogate for the “best-case scenario” due to its widely accepted components that are stable over time. Three search terms (“shoulder,” “examination,” and “shoulder exam”) were entered into the four online video resources most commonly accessed by orthopaedic surgery residents (VuMedi, G9MD, Orthobullets, and YouTube). Videos were captured and independently reviewed by three orthopaedic surgeons. Quality and accuracy were assessed in accordance with previously published standards.

Results

Of the 39 video tutorials reviewed, 61% were rated as fair or poor. Specific maneuvers such as the Hawkins test, O’Brien sign, and Neer impingement test were accurately demonstrated in 50, 36, and 27% of videos, respectively. Inter-rater reliability was excellent (mean kappa 0.80, range 0.79–0.81).

Conclusion

Our results suggest that information presented in open-access video tutorials featuring the physical examination of the shoulder is inconsistent. Trainee exposure to such potentially inaccurate information may have a significant impact on trainee education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Internet is an important tool for both patient and physician education. Several recent studies investigating web-based orthopaedic information available to patients have identified wide variability with regard to quality and accuracy [2, 6, 12–14, 17]. Furthermore, these studies demonstrated that access to high quality content is largely dependent upon search terms used [12, 14, 17]. Much like patients, healthcare providers are increasingly turning to the web-based content for clinical instruction and medical information [27].

Many open-access video tutorials focused on resident and physician education have rapidly emerged and gained popularity due, in large part, to their convenience, zero cost, and accessibility. Websites such as YouTube (www.YouTube.com) and VuMedi (www.vumedi.com) provide access to thousands of educational videos intended for orthopaedic healthcare providers. It was previously reported that more than 7200 educational websites dedicated to orthopaedics and orthopaedic-related issues could be found on the Internet [11]. It is important to note that while recent studies in non-orthopaedic disciplines espoused the utility of open-access content websites such as YouTube related to medical education [19, 25], others reported that the quality of the video content was suboptimal [10, 16, 23, 28].

To our knowledge, no studies have investigated the use of orthopaedic open-access video tutorials by trainees or the quality of information available. The purpose of this study was to determine the accuracy of internet-based instructional videos featuring the shoulder physical examination.

Materials and Methods

On April 4, 2012, the video databases of four open-access websites (VuMedi, G9MD, Orthobullets, and YouTube) were searched using the search terms “shoulder,” “examination,” and “shoulder exam.” The shoulder physical examination was selected because it is a routine component of resident education and is composed of a variety of maneuvers that can be studied. The inclusion criteria for selected videos were (1) videos involving physical examination of the shoulder, both comprehensive and those focusing on a specific aspect of the exam, and (2) videos featuring a healthcare professional demonstrating the exam. The term “healthcare professional” included medical doctors (any specialty), physical therapists, or athletic trainers. Only videos that identified the individual in the video as a healthcare professional either by verbal or written introduction (either in the video information or embedded in the video itself) were included. Videos were excluded if they did not address the physical exam of the shoulder or were not posted by a healthcare professional. In the case of high-volume search results (pertaining only to YouTube), only the first ten pages of each search term results were screened. YouTube search results populate based on the relevance to the search term. As such, it was decided that the first ten pages of any search would provide us with the highest concentration of videos relevant to our study and fitting the inclusion criteria. Duplicates were eliminated. Each video was independently assessed for correctness by three orthopaedic surgeons at various stages of training: a chief resident (rater 1), a junior resident (rater 2), and an intern (rater 3) (SAT, EYU, and EC).

To improve reviewer consistency and to minimize subjectivity, reviewers were provided a description of each maneuver as it was originally described in the literature (Table 1). Although several scoring systems were previously used in the non-orthopaedic literature, none was appropriate for the video content that was being assessed presently, as they were specifically tailored to the context of the clinical examination in question [10, 23, 28]. As such, included shoulder examination videos were assessed for accuracy with an ordinal customized grading system based on previously established grading criteria [2, 6, 12–14, 17, 20, 21]. An accuracy grade of 1 represented agreement with less than 25% of the information provided in the video, 2 represented agreement with 26–50%, 3 represented agreement with 51–75%, and 4 represented agreement with 76–100%. Scores were assigned according to the degree of accuracy with which each maneuver was performed (as compared to the aforementioned published standards). This included description of the test or maneuver, completeness of the demonstration, and accuracy of the interpretation of said test. In the case of the O’Brien sign, evaluation of the maneuver was deconstructed into three components: (1) arm position, (2) examiner action, and (3) verbal description and interpretation of the test. An individual score was assigned to each component. As such, the test was not assigned an overall cumulative score.

Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers’ scores for every exam maneuver was assessed by calculating a linearly-weighted Cohen’s kappa with 95% confidence intervals [26]. Kappa values ≥0.70 indicate good agreement, and kappa values ≥0.80 indicate excellent agreement [18]. Video quality was assessed for each examination maneuver by calculating the frequencies and percentages of videos that contained the procedure and, when present, the frequencies and percentages at each of the aforementioned quality grades. A similar analysis was conducted for overall video quality by considering each video in its entirety. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA).

There was no external funding for this study.

Results

Thirty-six unique open-access video tutorials met inclusion and exclusion criteria and were independently reviewed. The healthcare professionals featured in the videos reviewed included medical doctors and physical therapists. Inter-rater reliability was excellent (mean kappa 0.80, range 0.79–0.81).

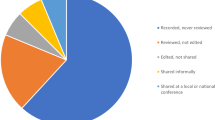

Of the 36 videos, 25 were from YouTube, seven from VuMedi, three from Orthobullets, and one video was from G9MD. YouTube videos had the overall highest number of inaccuracies, with 60% receiving a grade of 1 or 2 (Fig. 1a). VuMedi had the highest number of accurate ratings, with 37% receiving a grade of 4. When all videos were combined, overall, 9.2% were scored as grade 3 and 29.7% were scored grade 4. The remaining 61.1% of videos received a grade of 1 or 2, indicating low (<50%) accuracy. No single component of the exam received a perfect score in all 36 videos. The most consistently accurate maneuvers (grade 4) were acromioclavicular (AC) joint palpation (97.6% of videos), bicipital groove palpation (92.5% of videos), and the biceps Popeye sign (91.7% of videos; Table 2 and Fig. 1b). Range of motion testing accuracy was reduced because the test was incomplete in several videos. Provocative maneuvers such as the Neer impingement, Hawkins, and belly press tests were least often performed accurately, receiving a grade 4 only 26.1, 38.1, and 44.4% of the time, respectively (Fig. 1c). The most common error made in performing the Neer and Hawkins tests was not performing the maneuver in the scapular plane. The belly press test was inaccurate due to arm positioning with the elbow falling posterior to the mid-axillary line of the body. The most common error seen with the Yergason test was demonstrating resisted pronation instead of supination. The active compression test (O’Brien Sign) received a grade 4 only 42.5% of videos for arm position, 60.3% for actual performance of the maneuver, and 56% for interpretation. The most common errors identified for the active compression test were not adducting the arm 15° and not performing the “palm-up” portion of the exam.

a Percent accuracy of examination maneuvers as broken down by each website. b Overall percent accuracy of various common shoulder examination maneuvers (1 = <25% accurate; 2 = 25–50% accurate; 3 = 51–75% accurate; 4 >75% accurate). c Overall percent accuracy of various provocative maneuvers. (1 = <25% accurate; 2 = 25–50% accurate; 3 = 51–75% accurate; 4 >75% accurate).

Discussion

This study examined the accuracy of orthopaedic internet-based educational video content. Our results highlight the fact that the quality of educational orthopaedic videos on the internet appears to be inconsistent.

This study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, the grading system, while modeled closely after similar scales focused on Internet grading [12, 14, 17], is novel with regard to video content and subjective in nature. The grading method, however, demonstrated excellent inter-rater agreement. Second, the small sample size as well as the wide variability in the distribution of videos pulled from each site precludes us from drawing any conclusions regarding the content accuracy among the different sites. Furthermore, the video cohort was predominately from YouTube, with far fewer videos from other included sites. This further limits our ability to definitively comment on the accuracy of videos from the other sites. Third, limiting the search to the first ten pages of the search query in the YouTube results introduces a potential selection bias: it is possible that high-quality videos were inadvertently excluded due to their position in the results queue. Finally, the study represents a snapshot of video content available online at the time of the search. As such, our study may not accurately reflect the dynamic nature of the information stream. Since the search was performed, it is possible that the content available on the internet has changed significantly. We sought to mitigate this limitation, however, by selecting the shoulder examination for collection and analysis. Basic shoulder examination techniques are relatively well conserved and have not changed dramatically in recent time. As such, we felt this as the most stable representative tutorial for evaluation.

A review of relevant literature reveals that similar studies have been performed in other medical and surgical disciplines [1, 3–5, 7–10, 15, 16, 22–24, 28]. One study evaluated the quality of YouTube videos addressing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [23]. The authors queried YouTube videos on a single day using four search terms and evaluated the videos for accuracy and “view-ability.” They determined that only 63% of the 52 videos actually demonstrated the correct compression-ventilation ratio and 19% incorrectly recommended checking for pulse. The authors concluded that although YouTube videos were a potentially valuable source of learning material, they frequently omitted crucial information and presented wholly inaccurate information. Another study evaluated the quality of cardiac auscultation tutorial videos on YouTube [10]. The authors analyzed a total of 22 videos for audiovisual quality, teaching quality, and comprehensiveness and found the quality of the content to be highly variable. They concluded that few of the many video tutorials available on cardiac auscultation on YouTube were accurate. More recently, the same group performed a similar analysis on the quality of YouTube videos focused on respiratory auscultation [28]. Of the 6022 videos located, only 36 met inclusion criteria. The quality of these videos, as one might expect, was highly variable. No videos achieved the highest score. The authors emphasized the high volume of poor-quality and factually incorrect educational content, which was widely available and the difficulty of locating the small number of valuable, informative videos. The authors urged institutions engaged in healthcare education to guide their trainees to quality internet educational resources and call for a standardized moderating system that could improve content quality. Similar results were found by other investigators for the inaccuracy of videos focused on the cardiovascular and respiratory physical examination [5] and knee arthrocentesis [16]. The authors conclude that the vast majority of educational videos on YouTube are unsuitable for teaching purposes. Our results were consistent with this assessment, demonstrating that YouTube videos in particular have an unacceptably high frequency of inaccuracies. Given the difficulty of regulating content on YouTube, these results are not surprising. Video content on more regulated sites like VuMedi and Orthobullets appears to be more accurate; however, the quality of the videos was inconsistent. Our results suggest that VuMedi videos are the most consistently accurate.

Open-access video platforms not only facilitate distribution of educational material, but also allow swift dissemination of misinformation. Thus, quality control is of paramount importance. This study suggests that the quality of information available is inconsistent at best. We recognize that regulating public domain sites such as YouTube is nearly impossible, and thus, the quality of content will always beholden to those who choose to submit content. As such, the task of ensuring that trainees have access to high-quality instructional content falls squarely on the shoulders of the orthopaedic community—be it via the national and international societies, individual academic centers, or a combination of the two.

The first step in addressing this issue is to acknowledge the central role that video-based education has assumed in resident education, brought on by the popularity of advanced mobile devices. Next, the absence of a large, well-regulated video database should be recognized. This information gap is demonstrated in our study by the prevalence of YouTube-based videos and the relative paucity of videos from orthopaedic websites. orthopaedic trainees will inevitably seek out web-based information as it is needed. Unfortunately, as it stands now, the majority of instructional orthopaedic videos are found on YouTube. This fact should be the single-most influential driving force behind improving and standardizing available educational video content. One way to address this issue is by establishing internal educational platforms where content is regulated by a select group of specialists. One such example is Hospital for Special Surgery eAcademy website (https://hss.classroom24-7.com), which is accessible by both trainees and patients. In reality, however, the solution to this problem most likely lies within pre-existing educational platforms whose major purpose is trainee education—websites such as Orthobullets or Wheeless (www.wheelessonline.com). These sites’ main goal is to convey high-yield orthopaedic information in an easily accessible format. Additionally, such websites have the advantage of not being bound by specialty or geographic location, which allows them to cover a large spectrum of information and reach a large population of trainees.

Ultimately, whether educational content is produced by individual entities or by public websites is less important; the key is pooling of information, which is then evaluated against predetermined standards by experts in the field. The result would then be a collection of reliable, standardized videos provided on a single platform (website, phone application, etc.) to a population of trainees who have been directed to this platform by their respective institutions.

The results of this study suggest that information presented in open-access video tutorials featuring the physical examination of the shoulder is inconsistent. Internet-based learning has emerged into medical student, resident, and fellow education and has been recognized as a powerful teaching tool. These resources are likely to further penetrate the education market in the face of technological advances in mobile devices and smartphone applications. Keeping in mind the ubiquitous nature of online educational media and the inconsistency of its content, we believe that academically orientated orthopaedic institutions have a responsibility to both acknowledge this method of learning and to guide orthopaedic trainees to accurate educational resources.

References

Akgun T, Karabay CY, Kocabay G, et al. Learning electrocardiogram on YouTube: how useful is it? J Electrocardiol. 2014; 47(1): 113-117.

Aslam N, Bowyer D, Wainwright A, et al. Evaluation of Internet use by paediatric orthopaedic outpatients and the quality of information available. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005; 14(2): 129-133.

Azer SA. Understanding pharmacokinetics: are YouTube videos a useful learning resource? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014; 18(13): 1957-1967.

Azer SA, Aleshaiwi SM, Algrain HA, et al. Nervous system examination on YouTube. BMC Med Educ. 2012; 12: 126-6920. 12-126.

Azer SA, Algrain HA, AlKhelaif RA, et al. Evaluation of the educational value of YouTube videos about physical examination of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 15(11): e241.

Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Steinberg DR, et al. Evaluating the source and content of orthopaedic information on the Internet. The case of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000; 82-A(11): 1540-1543.

Bezner SK, Hodgman EI, Diesen DL, et al. Pediatric surgery on YouTube: is the truth out there? J Pediatr Surg. 2014; 49(4): 586-589.

Brna PM, Dooley JM, Esser MJ, et al. Are YouTube seizure videos misleading? Neurologists do not always agree. Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 29(2): 305-307.

Burton A. YouTube-ing your way to neurological knowledge. Lancet Neurol. 2008; 7(12): 1086-1087.

Camm CF, Sunderland N, Camm AJ. A quality assessment of cardiac auscultation material on YouTube. Clin Cardiol. 2013; 36(2): 77-81.

Clough JF, Abdelmaksoud MA, Kamstra PE, et al. Current concepts review. Internet resources for orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000; 82(2): 288-289.

Dy CJ, Taylor SA, Patel RM, et al. The effect of search term on the quality and accuracy of online information regarding distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2012; 37(9): 1881-1887.

Dy CJ, Taylor SA, Patel RM, et al. Does the quality, accuracy, and readability of information about lateral epicondylitis on the internet vary with the search term used? Hand. 2012; 7(4): 420-425.

Fabricant PD, Dy CJ, Patel RM, et al. Internet search term affects the quality and accuracy of online information about developmental hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013; 33(4): 361-365.

Fat MJ, Doja A, Barrowman N, et al. YouTube videos as a teaching tool and patient resource for infantile spasms. J Child Neurol. 2011; 26(7): 804-809.

Fischer J, Geurts J, Valderrabano V, et al. Educational quality of YouTube videos on knee arthrocentesis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013; 19(7): 373-376.

Garcia GH, Taylor SA, Dy CJ, et al. Online resources for shoulder instability: what are patients reading? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014; 96(20): e177.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33(1): 159-174.

Logan R. Using YouTube in perioperative nursing education. AORN J. 2012; 95(4): 474-481.

Mathur S, Shanti N, Brkaric M, et al. Surfing for scoliosis: the quality of information available on the Internet. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30(23): 2695-2700.

Morr S, Shanti N, Carrer A, et al. Quality of information concerning cervical disc herniation on the Internet. Spine J. 2010; 10(4): 350-354.

Muhammed L, Adcock JE, Sen A. YouTube as a potential learning tool to help distinguish tonic-clonic seizures from nonepileptic attacks. Epilepsy Behav. 2014; 37: 221-226.

Murugiah K, Vallakati A, Rajput K, et al. YouTube as a source of information on cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2011; 82(3): 332-334.

Raikos A, Waidyasekara P. How useful is YouTube in learning heart anatomy? Anat Sci Educ. 2014; 7(1): 12-18.

Sharoff L. Integrating YouTube into the nursing curriculum. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011; 16(3): 6.

Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005; 85(3): 257-268.

Sinkov VA, Andres BM, Wheeless CR, et al. Internet-based learning. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004; 421(421): 99-106.

Sunderland N, Camm CF, Glover K, et al. A quality assessment of respiratory auscultation material on YouTube. Clin Med. 2014; 14(4): 391-395.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ekaterina Urch, MD; Samuel A. Taylor, MD; Elizabeth Cody, MD; Peter D. Fabricant, MD, MPH; Jayme C. Burket, PhD; and Stephen J. O’Brien, MD, MBA have declared that they have nothing to disclose. David Dines, MD, reports personal fees from Biomet, outside the work. Joshua S. Dines, MD, reports personal fees from Conmed and Arthrex, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

N/A

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Additional information

Work performed at Hospital for Special Surgery

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urch, E., Taylor, S.A., Cody, E. et al. The Quality of Open-Access Video-Based Orthopaedic Instructional Content for the Shoulder Physical Exam is Inconsistent. HSS Jrnl 12, 209–215 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-016-9508-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-016-9508-6