Abstract

Background

Concern exists over the quality, accuracy, and accessibility of online information about health care conditions. The goal of this study is to evaluate the quality, accuracy, and readability of information available on the internet about lateral epicondylitis.

Methods

We used three different search terms (“tennis elbow,” “lateral epicondylitis,” and “elbow pain”) in three search engines (Google, Bing, and Yahoo) to generate a list of 75 unique websites. Three orthopedic surgeons reviewed the content of each website and assessed the quality and accuracy of information. We assessed each website’s readability using the Flesch–Kincaid method. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA with post hoc pairwise comparisons.

Results

The mean reading grade level was 11.1. None of the sites were under the recommended sixth grade reading level for the general public. Higher quality information was found when using the terms “tennis elbow” and “lateral epicondylitis” compared to “elbow pain” (p < 0.001). Specialty society websites had higher quality than all other websites (p < 0.001). The information was more accurate if the website was authored by a health care provider when compared to non-health care providers (p = 0.003). Websites seeking commercial gain and those found after the first five search results had lower quality information.

Conclusions

Reliable information about lateral epicondylitis is available online, especially from specialty societies. However, the quality and accuracy of information vary significantly with the search term, website author, and order of search results. This leaves less educated patients at a disadvantage, particularly because the information we encountered is above the reading level recommended for the general public.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The internet is rapidly growing as a means for patients to access information about health conditions [15, 23, 28]. The internet’s relative ease of use and versatility give patients an unprecedented opportunity to independently investigate medical diagnoses and treatments [31]. This increase in patient access to health care topics has caused many health care providers to modify their practices to incorporate online information into their patient encounters [19, 31]. However, there is concern about the quality, accuracy, and readability of the information available on the internet about health care conditions [11, 16, 31]. Recent health policy has increased the role of shared decision making and patient-centered outcomes research [24], which has subsequently emphasized the need for patient access to accurate and understandable health care information online.

The quality of patient-directed health information available on the internet has been related to commercial gain [5, 17, 20, 29]. While physician specialty organizations have provided high-quality information, these websites are often written at a level above comprehension level of the general public [2, 4, 8, 12, 14, 22, 26, 30, 32]. Because poorly informed patients may affect shared decision making, physicians and the general public must be aware of the potential for misinformation on the internet.

Baseline inequality in access to the internet (the so-called digital divide) [6] may be compounded by a less apparent disparity. Because access to information on the internet is largely filtered by search engines, we asked whether the patient education information retrieved was dependent on the search term used. In the current study, we evaluated the quality, accuracy, and readability of information available about lateral epicondylitis on the internet. We used three different search terms of varying sophistication [“lateral epicondylitis,” (LE) “tennis elbow,” (TE) and “elbow pain” (EP)] in three different searches and analyzed the patient education information available through those search efforts. We hypothesized that the quality, accuracy, and readability of information about lateral epicondylitis would vary depending on the search term used.

Materials and Methods

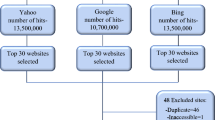

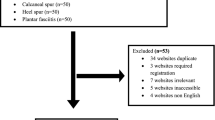

We selected the search terms “lateral epicondylitis,” “tennis elbow,” and “elbow pain” to simulate the variability of search terms used when seeking information about lateral epicondylitis. We entered each of the three search terms into Google, Yahoo, and Bing on September 19, 2011 within a single session for a total of nine separate searches. We selected these search engines because they represent approximately 93 % of internet searches performed [10]. Search histories and internet caches (including cookies) were cleared between searches. We compiled the first 25 results from each search and eliminated duplicate results and nonfunctional websites, leaving a list of 100 unique websites (Fig. 1). We accessed all of the websites during a 2-h period and created an electronic capture of each website after excluding 16 websites with only news items or website menus (without information content). We also excluded sites from further review if they contained materials explicitly intended for peer review (six sites). Seventy-eight unique websites remained (Fig. 1).

We assessed the quality and accuracy of the information on the websites in a manner similar to prior investigations of information about scoliosis [18] and disc herniation [13, 20]. We generated a content quality score that included 30 items related to the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of lateral epicondylitis (Table 1). The 30 items in the content quality score represent what should be presented to patients if they are seeking information about LE on the internet and were largely based on the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ website about LE [1]. Similar to prior investigation [13], we reviewed the website quality and awarded one point if a website contained correct information for each item, with a maximum score of 30. Three independent reviewers evaluated the quality of each website using an identical electronic capture of the website. The scores of the three reviewers were averaged to provide a mean score for each website.

To assess website accuracy, three independent appraisers rated the accuracy of information on the website on a scale of 1 to 4 [18, 20]. An accuracy score of 1 represents agreement with less than 25 % of the information on the website; 2 represents agreement with 26–50 %; 3 represents agreement with 51–75 %; and 4 represents agreement with 76–100 %. The summed scores of the three appraisers were analyzed with a maximum score of 12 [18, 20].

The readability of each website was evaluated using the Flesch–Kincaid (FK) method of analysis, which has previously been used when evaluating information about orthopedic [2, 26, 30] and upper extremity conditions [33]. After preparing the text identically to Wang and colleagues [33], we used Microsoft Word (Redmond, WA) to determine the FK readability grade level of each website. The FK grade level indicates that a person who has completed that academic grade level will be able to read and comprehend the material. A higher FK grade level is assigned to a material that is more difficult to read and to understand [2, 26].

We grouped the websites by the search term used to find them—“lateral epicondylitis,” “tennis elbow,” or “elbow pain.” If a website was retrieved using more than one search term, we categorized the website by the search term that yielded the earliest result. We also grouped the websites by the highest priority result (“hits” 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21–25). We grouped websites into those with an FK score above sixth grade level and into those at or below sixth grade level in accordance with prior recommendations for patient education materials [7, 9, 34]. Additionally, we noted whether the websites were seeking commercial gain (contained advertisements for elbow or sports-related products or services). Finally, we categorized the websites by authorship: health care provider (HCP; physician, nurse, or physical therapist with explicitly stated credentials), non-HCP, or physician specialty society. We reviewed the websites found using the term “elbow pain” and excluded them from analysis if there was no information about lateral epicondylitis (Fig. 1).

Descriptive statistics were calculated for quality score, summed accuracy assessment, and FK level. Normality of the data was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis; non-normally distributed data were analyzed using nonparametric tests. Analysis of variance (for normally distributed data) and Kruskal–Wallis tests (for non-normally distributed data) with post hoc pairwise comparisons were used to determine any difference in quality, accuracy, and readability based on search term used, order of search results, and website author. Independent sample t tests (for normally distributed data) or Mann–Whitney U tests (for non-normally distributed data) were used to determine any difference in quality, accuracy, or readability based on whether a website was seeking commercial gain. Correlation analysis was also used to evaluate for an association between quality and FK score, as well as accuracy and FK score. Multivariate regression models were constructed to determine whether website quality or accuracy was significantly influenced by search term used while controlling for website FK score. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05 in all statistical tests.

Results

A Wide Range of Quality, Accuracy, and Reading Levels Exists Across all Lateral Epicondylitis Content on the Internet

Seventy-eight unique websites were initially included for review, but three were excluded because they did not contain information about lateral epicondylitis. Of the 75 websites included for final review, quality [11.9 (mean) ± 6.1 (SD) of a maximum score of 30; range 0 to 30] and accuracy (10.5 ± 2.5 of a maximum score of 12; range 3 to 12) varied greatly. The average FK grade level was 11.1 ± 2.1 (range, 6.4 to 16.3). None of the 75 websites had the recommended FK score below or equal to the sixth grade reading level. Five of the 75 (6.7 %) websites had an FK score below the eighth grade reading level. Data for quality and FK score were normally distributed, while data for accuracy were not normally distributed. Parametric statistical tests were used to compare quality and FK scores, while nonparametric tests were used to compare accuracy.

Of the 75 total websites, 30 were identified using the search term “lateral epicondylitis,” 25 with “tennis elbow,” and 20 with “elbow pain.” We categorized 40 (51.3 %) as seeking commercial gain. Twenty-six websites were authored by HCP, 45 were written by non-health care providers, and 4 were written by physician specialty societies.

Quality of Information About Lateral Epicondylitis, but Not Accuracy or Reading Level, Is Dependent on Search Term Used

There was a significant difference in quality when comparing the “LE,” “TE,” and “EP” groups (p < 0.001; ANOVA). The post hoc pairwise comparisons demonstrated a significant difference between the “LE” (14.9 ± 5.7) and “EP” groups (6.4 ± 4.3; p < 0.001), as well as a significant difference between the “TE” (12.7 ± 4.7) and “EP” groups (p < 0.001). There was no difference in quality between “LE” and “TE.”

There was no difference in accuracy when comparing the different search term groups. The FK readability scores also did not vary significantly between the different search term groups.

A multivariate linear regression model was constructed to evaluate the influence of search term on quality while controlling for the FK score of each website. When controlling for FK level, search term significantly affects website quality (p < 0.001; β = −4.519).

Website Authorship and Commercial Gain, but not Order of Return of Search Engine Results, Affect Quality and Accuracy

There was a significant difference in website quality when comparing websites by authorship (p = 0.001; ANOVA), with the post hoc pairwise comparisons showing a significantly higher quality on specialty society websites (22.3 ± 5.6) when compared to HCP websites (12.2 ± 5.4; p = 0.001) and when compared to non-HCP websites (10.7 ± 5.7; p < 0.001).

The accuracy of the information was significantly different between the authorship groups (p = 0.001; Kruskal–Wallis test), with the post hoc pairwise comparisons showing a significantly higher accuracy on HCP-authored websites (11.3 ± 2.0) when compared to non-HCP websites (10.0 ± 2.7; p = 0.002). There was no statistically significant difference between accuracy of specialty society sites (12.0 ± 0.0) and websites authored by HCP (p = 1.0) and non-HCP (p = 0.052). There was no significant difference in FK score regardless of who authored the site.

Websites seeking commercial gain had significantly lower quality (10.0 ± 5.7; n = 39 vs 13.9 ± 5.8; n = 36; p = 0.005; t test). There was no significant difference in accuracy or FK score based on the presence of commercial gain.

There was no significant difference in quality, accuracy, and FK score when comparing the websites by the order of search results (“hits” 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21–25). There was no significant difference in quality or FK score when comparing the websites that were in the first five hits to all other websites. However, websites found in the first five search results (11.8 ± 0.6; n = 16) were more accurate than websites found after the first five search results (10.1 ± 2.7; n = 59; p = 0.008).

Discussion

Patients are rapidly turning to the internet as a source of health care information [15, 21, 25, 28]. There is concern among physicians that the information that patients are finding is not entirely accurate or understandable to the general public [11, 16, 31]. In the current study, we have shown that the quality of the information about lateral epicondylitis depends on a variety of factors, including the search term used, the author of the website, and whether a website was seeking commercial gain. This potential for misinformation may make the process of shared decision making unnecessarily more challenging for a physician and patient.

While we attempted to evaluate websites based on what patients should know, the lack of consensus among health care professionals about the pathophysiology, natural history, and treatment of this condition may make this task relatively impossible. We attempted to remove any personal biases about lateral epicondylitis from the website evaluations by basing the scoring system on the items included on the AAOS patient education website [1]. The scoring system we have used should not be considered as a comprehensive assessment of knowledge about lateral epicondylitis since the body of knowledge is still in evolution. Rather, our assessments should be viewed as the ability of a website to appropriately represent a group of commonly believed concepts about lateral epicondylitis.

Patients who are more educated are more likely to encounter high-quality information about the condition that they are seeking. In the current study, we have shown that searches using the term “lateral epicondylitis” and “tennis elbow” both yielded information of significantly higher quality (with regard to lateral epicondylitis) than a search using the term “elbow pain.” While “elbow pain” is admittedly a less specific search term (particularly when grading websites based on their content about lateral epicondylitis), we tried to minimize the effect of this limitation by excluding websites that were found using the term “elbow pain” but did not include information about lateral epicondylitis. There is a fair likelihood (51 %) that patients seeking information about lateral epicondylitis will encounter a website that is seeking commercial gain, which lowers the quality of the information that is ultimately found. Websites authored by health care providers were significantly more accurate than those authored by non-health care providers, suggesting that health care providers should play a more active role in providing information to patients on the internet. Regardless, patients seeking information about lateral epicondylitis will find websites that are written near the 11th grade level on average. None of the websites met the recommendation of a below sixth grade reading level. This is particularly concerning because less educated patients are at a particular disadvantage. Not only are they less likely to have access to the internet but also the quality of information they find will be influenced by the sophistication and specificity of the search term used, and they will likely be unable to understand the materials that they find. Furthermore, our results suggest that individuals who are informed about their diagnosis (“lateral epicondylitis”) will find better quality information for their conditions, but individuals who are unaware of their diagnosis (“elbow pain”) are less likely to find high-quality information. This presents an opportunity for physicians to take advantage of the internet’s capabilities by educating their patients and directing to reliable sources of information on the internet about their diagnosis [27].

Although the order of search results did not significantly influence the quality, accuracy, and readability in our study, the role of search engines in controlling access to information cannot be underestimated. Health care providers (and the specialty societies to which they belong) should work either independently, or in conjunction with search engines programmers, to ensure that high-quality, accurate, and understandable information about health care conditions is presented to patients on the internet. Our results show that more accurate information is found within the first five search results. Search engine programmers should continue to prioritize these websites but should also strive to direct users towards information written at an appropriate grade level for the general public. Patients who do not have the ability to access, understand, and apply health care information are at a disadvantage in utilizing and benefiting from health care services [3]. We must ensure that these patients are not left behind as the internet continues to expand as a portal for health care information.

References

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis)—your orthopaedic connection—AAOS. 2009. Available at: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00068. Accessed 03 Feb 2012.

Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;1:199–204.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;2:97–107.

Bluman EM, Foley RP, Chiodo CP. Readability of the patient education section of the AOFAS website. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;4:287–91.

Butler L, Foster NE. Back pain online: a cross-sectional survey of the quality of web-based information on low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;4:395–401.

Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;6:671–92.

Cotugna N, Vickery CE, Carpenter-Haefele KM. Evaluation of literacy level of patient education pages in health-related journals. J Community Health. 2005;3:213–9.

D'Alessandro DM, Kingsley P, Johnson-West J. The readability of pediatric patient education materials on the world wide web. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;7:807–12.

Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1996.

Experian Hitwise. Search engine analysis. 2011. Available at: http://www.hitwise.com/us/datacenter/main/dashboard-23984.html. Accessed 21 Dec 2011.

Eysenbach G, Diepgen TL. Towards quality management of medical information on the internet: evaluation, labelling, and filtering of information. BMJ. 1998;7171:1496–500.

Freda MC. The readability of American Academy of Pediatrics patient education brochures. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;3:151–6.

Greene DL, Appel AJ, Reinert SE, et al. Lumbar disc herniation: evaluation of information on the internet. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;7:826–9.

Greywoode J, Bluman E, Spiegel J, et al. Readability analysis of patient information on the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery website. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;5:555–8.

Gupte CM, Hassan AN, McDermott ID, et al. The internet—friend or foe? A questionnaire study of orthopaedic out-patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;3:187–92.

Jariwala AC, Kandasamy, Abboud RJ, et al. Patients and the internet: a demographic study of a cohort of orthopaedic out-patients. Surgeon. 2004;2:103–6.

Li L, Irvin E, Guzman J, Bombardier C. Surfing for back pain patients: the nature and quality of back pain information on the internet. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;5:545–57.

Mathur S, Shanti N, Brkaric M, et al. Surfing for scoliosis: the quality of information available on the internet. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;23:2695–700.

McMullan M. Patients using the internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;1–2:24–8.

Morr S, Shanti N, Carrer A, et al. Quality of information concerning cervical disc herniation on the internet. Spine J. 2010;4:350–4.

Neelapala P, Duvvi SK, Kumar G, et al. Do gynaecology outpatients use the internet to seek health information? A questionnaire survey. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;2:300–4.

Polishchuk DL, Hashem J, Sabharwal S. Readability of online patient education materials on adult reconstruction web sites. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):716–9.

Rahmqvist M, Bara AC. Patients retrieving additional information via the internet: a trend analysis in a Swedish population, 2000–05. Scand J Public Health. 2007;5:533–9.

Rangel C. United States Congress–House of Representatives–Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2009.

Rokade A, Kapoor PK, Rao S, et al. Has the internet overtaken other traditional sources of health information? Questionnaire survey of patients attending ENT outpatient clinics. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;6:526–8.

Sabharwal S, Badarudeen S, Unes Kunju S. Readability of online patient education materials from the AAOS web site. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;5:1245–50.

Sethuram R, Weerakkody AN. Health information on the internet. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;2:119–21.

Trotter MI, Morgan DW. Patients' use of the internet for health related matters: a study of internet usage in 2000 and 2006. Health Informatics J. 2008;3:175–81.

Ullrich Jr PF, Vaccaro AR. Patient education on the internet: opportunities and pitfalls. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;7:E185–8.

Vives M, Young L, Sabharwal S. Readability of spine-related patient education materials from subspecialty organization and spine practitioner websites. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;25:2826–31.

Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the web—the impact of internet use on health care and the physician–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;3:218–24.

Wallace LS, Lennon ES. American Academy of Family Physicians patient education materials: can patients read them? Fam Med. 2004;8:571–4.

Wang SW, Capo JT, Orillaza N. Readability and comprehensibility of patient education material in hand-related web sites. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;7:1308–15.

Weiss BD. Health literacy and patient safety: Help patients understand—a manual for clinicians. 2007. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/367/healthlitclinicians.pdf. Accessed 21 Dec 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Dy, C.J., Taylor, S.A., Patel, R.M. et al. Does the quality, accuracy, and readability of information about lateral epicondylitis on the internet vary with the search term used?. HAND 7, 420–425 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-012-9443-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-012-9443-z