Abstract

The present study adopted the structural equation modeling approach to examine Chinese university students’ metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing. In particular, this research explored whether awareness in metacognition can foster critical thinking and, thus, lead to enhancement in academic writing. The measure for exploring metacognitive writing strategies covered metacognitive knowledge and regulation in academic writing. The measure for understanding learners’ critical thinking encompassed the following five skills: inference, recognition of assumptions, deduction, interpretations, and evaluation of arguments. The academic writing assessment was based on an internal test. The participants consisted of 644 third-year students from a Chinese university. Three models tested: (1) the role of metacognition in academic writing; (2) the role of metacognition in critical thinking; and (3) correlations between metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing. The results indicated significant relationships between the three variables, and the implications based on these findings were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the present study, academic writing is defined as a means or a skill in using English to document scientific knowledge, communicate research processes, describe research outcomes, and outline research implications. Academic writing, is thus, challenging for students learning English as a foreign language (EFL), whose writing is greatly impacted by their language proficiency level. Another reason may be that EFL teaching and learning are often exam-oriented. In addition, in EFL contexts, difficulties associated with academic writing can be exacerbated for learners who receive limited input in the target language. Although writing is an indispensable component of English courses, academic writing rarely receives sufficient attention. For example, writing instruction generally focuses on grammatical rules and accuracy in language use, with comparatively little attention given to process-oriented writing instruction (Woodrow, 2011). In EFL teaching and learning, “writing requires sophisticated levels of cognitive functioning that may impose great challenges” for student writers (Bui & Kong, 2019, p. 358). Relevant factors that influence academic writing also include time constraints (Ozarska, 2008), metacognitive activities and co-regulation patterns (Teng, 2021), learners’ motivation level (Troia et al., 2013), and English language proficiency level (Teng & Huang, 2019). Despite a need to foster learners’ writing-related motivation, teachers have not yet recognized the role of metacognitive regulation in writing (Hall & Goetz, 2013; Qin & Zhang, 2019). EFL learners may thus find academic writing challenging, and learners’ awareness of metacognitive strategies may play an important role in academic writing (Ruan, 2014; Teng, 2016).

Academic writing is a cognitive activity during which student writers engage in metacognition (Teng et al., 2022b). This entails student writers being aware of their thought processes while learning to write and using metacognitive awareness to improve their thinking. As described by Hacker et al. (2009), writing reflects “applied metacognitive monitoring and control” (p. 160). This argument highlights the need to explore writing from a metacognitive perspective, such as through planning, goal setting, translating, monitoring, revising, and evaluating (McCormick, 2003). However, learners demonstrate differences in their ability to develop “self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions” in writing (Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997, p. 76). This circumstance reveals disparities in learners’ writing-related metacognition levels; for example, some student writers are more involved in learning to write, while others are passive about cultivating self-regulation for writing (Graham & Harris, 2000; Teng et al., 2022a).

Metacognitive knowledge is also connected with writing performance (Graham, 2006; Teng & Zhang, 2021). The development of metacognitive knowledge entails multiple strategies (e.g., self-questioning, thinking aloud while performing a task, and creating graphic representations) (Gammil, 2006). Metacognitive awareness is the result of metacognitive experiences and may lead to the acquisition of metacognitive knowledge. Metacognitive awareness helps learners identify learning obstacles as early as possible and then adjust their strategies to promote goal attainment (Sato, 2022). The skillful use of metacognitive strategies also distinguishes highly skilled writers from less skilled writers (Sato, 2022). Novice and struggling student writers use self-regulatory processes minimally, which can result in a simplistic compositional approach, named “knowledge telling” (Harris et al., 2010, p. 234). Put simply, these learners often record information they perceive as topic-related, but rarely conduct a critical evaluation of their ideas, text information organization, or whether their writing aligns with their task, audience, and genre. Given some learners’ lack of “self-awareness, self-motivation, and behavioral skill” (Zimmerman, 2002, p. 65), they may be unable to use metacognitive strategies to ensure that “the production of meaning is in conformance with their goals for writing” (Hacker et al., 2009, p. 163). Metacognition thus predicts writing performance.

Another challenge in EFL academic writing is limited critical thinking skills (Pally, 2001). For instance, students who lack critical thinking skills may be unable to engage in reasoning and argumentation in academic writing, which involves grasping the claims or perspectives presented in the literature and synthesizing claims from various sources. Critical thinking skills also involve the ability to delve into the social context of claims (Shor, 1992) or to question, challenge, and evaluate them (Ramanathan & Atkinson, 1999). Student writers formulate ideas based on their understanding, synthesis, and questions and then present these ideas in written forms using appropriate rhetorical conventions. Critical thinking is a “creative strategy for visualizing a path through new and challenging ideas,” with which learners can navigate unfamiliar territory while learning to write (Chaffee, 2015, p. 69). In the realm of teaching composition, writing programs in many locations emphasize students’ critical thinking skills (Atkinson & Ramanathan, 1995). However, as Atkinson (1997) pointed out, “the locus of thought is to be within the individual” (p. 80). This position highlights individual differences in critical thinking skills. Considering these discrepancies and obstacles to developing critical thinking skills for writing, it is essential to further explore critical thinking skills in academic writing.

One crucial factor related to the cultivation of critical thinking skills is the development of metacognitive awareness. Critical thinking is associated with the use of cognitive skills or strategies (Schroyens, 2005) and metacognition (Schoenfeld, 1987). In particular, “the enhancement of thinking” was found to be dependent on the ability of an individual to “organize knowledge and internally represent it” (Schoenfeld, 1987, p. 211). Based on this argument, knowledge enhancement for critical thinking and the process of organizing knowledge is one component of metacognition.

Despite apparent links between metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing, scholars have yet to explore this connection. The hypothesis in the present study is that learners who build awareness in metacognition are more prepared to think critically, leading to better academic writing performance. This assumption is based on the connection between metacognition and academic writing, documented by Teng et al. (2022b). This assumption also reflects Halpern’s (1998) four-part model, which includes “a dispositional or attitudinal component, instruction in and practice with critical thinking skills, structure-training activities, and a metacognitive component used to direct and assess thinking” (p. 450). Presumably, learners who establish metacognitive skills, such as monitoring their thinking process, evaluating their progress, and making decisions about their mental effort can become effective critical thinkers when writing. Magno (2010) evaluated two models connecting metacognition and critical thinking skills. Both models indicate that metacognition correlates with critical thinking. Learners with stronger critical thinking skills are likely to engage in deep-level processing, while monitoring and controlling their pursuit of a goal. It is thus useful to adopt the structural equation modeling approach to assess the associations between metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing performance. The present study aims to provide insight into how metacognition functions as an executive ability that aids in enhancing the thinking skills necessary for writing. The results also inform a theoretical conceptualization connecting these three variables, i.e., metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing.

Literature review

Metacognition

Flavell (1979) first proposed the notion of metacognition, which refers to individuals’ awareness and the regulation of their own thinking or cognitive processes. Flavell (1979) suggested that metacognition is a representation of cognitive enterprises that occurs through the actions of and interactions among the following four classes of phenomena: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals, and strategies. Flavell (2004) also suggested a link between the concept of metacognition and the theory of mind. While metacognition deals mainly with task-related mental processes, such as strategies improving cognitive performance and knowledge related to one’s own mental states, the theory of mind refers to knowledge about mental states, including desires, thoughts, and beliefs. Flavell’s work triggered a large amount of research in the field of educational psychology. Among these works, Efklides (2008) is the most influential in terms of documenting a multifaceted and multilevel model of metacognition and levels of functioning, as well as its relations with self-regulation, co-regulation, and other-regulation. In particular, metacognition reflects a process in which learners are “consciously aware of the monitoring and control processes” (Efklides, 2008, p. 278). Monitoring and control are two important functions that connect the three levels of metacognition, i.e., the non-conscious level, personal awareness level, and social level.

The term metacognition has been defined in several ways. Metacognition is inherently multifaceted, as it can help learners build the skills needed to “control cognition in multiple domains” (Schraw, 2001, p. 7). A common conceptualization frames metacognition as a construct consisting of two components, namely, a knowledge component and an executive regulation component (Schraw, 1998; Wenden, 1998). Metacognitive knowledge is the segment of an individual’s “stored world knowledge that has to do with people as cognitive creatures and with their diverse cognitive tasks, goals, actions, and experiences” (Flavell, 1979, p. 906). Jacobs and Paris (1987) divided metacognitive knowledge into the following three components: declarative, procedural, and conditional types. Declarative knowledge, also described as content knowledge, refers to a learner’s factual knowledge. This form of knowledge covers skills, intellectual resources, strategies, tasks, and personal affective factors related to processing abilities. Procedural knowledge, also called task knowledge, involves the execution of the metacognitive strategies and skills required for task implementation. Conditional knowledge, otherwise known as strategic knowledge, embodies a learner’s ability to determine when, where, and why certain strategies are selected and resources are allocated to perform a task. Conditional knowledge may start out as declarative knowledge (knowing what to do when and why) to accumulate procedural knowledge, but eventually it becomes integrated with procedural knowledge (for a detailed review of the types of metacognitive knowledge, see McCormick, 2003).

In addition to metacognitive knowledge, Efklides (2008) posits that metacognition encompasses metacognitive experiences and skills. Metacognitive experiences refer to individuals’ feelings and judgments about their experiences when processing the information needed to perform a task (Efklides, 2006). Such experiences connect a person with a task; for instance, metacognitive experiences involve an individual’s awareness of task features and effort devoted to cognitive processes in relation to pre-determined goals. Feelings inform individuals about “a feature of cognitive processing”, for which learners perform in an experiential way, i.e., in the form of a feeling of knowing or a feeling of confidence (Efklides, 2006, p. 5). Feelings of knowing, familiarity, confidence, and even being challenged are pivotal to sustaining effort for self-regulated learning (Efklides, 2001), which was described as “the ways in which individuals regulate their own cognitive processes” (Puustinen & Pulkkinen, 2001, p. 269).

Metacognitive skills refer to learners’ deliberate use of strategies to control cognition; these skills have also been termed metacognitive strategies (Efklides, 2006). Such strategies focus on executive control processes, including “selective attention, conflict resolution, error detection, and inhibitory control” (Shimamura, 2000, p. 313). Metacognitive skills/strategies consist of orientation, planning, cognitive processing, monitoring, and evaluation approaches (Veenman & Elshout, 1999). Efklides et al. (2003) argued that metacognitive skills are not analogous to self-regulation. However, Pintrich et al. (2000) suggested that metacognitive skills constitute part of the self-regulation process.

Schraw and Moshman (1995) described metacognitive regulation as “metacognitive activities that help control one’s thinking or learning” (p. 354). Veenman et al. (2006) defined metacognitive regulation as learners’ efforts to monitor and control their cognitive processes through executive functions. Metacognitive regulation involves three basic activities, including planning, monitoring, and evaluating (Schraw, 1998). Planning refers to learners’ efforts to identify the appropriate strategies and resources needed to complete relevant tasks. Monitoring represents learners’ awareness in tracking their task performance. Evaluating captures learners’ abilities to assess their regulatory processes and learning outcomes. Schraw and Dennison (1994) added debugging strategies and information management strategies as two important components of metacognitive regulation. Debugging strategies refer to learners’ efforts to correct errors related to comprehension and performance. Information management strategies refer to learners’ abilities to process, organize, elaborate on, and summarize information.

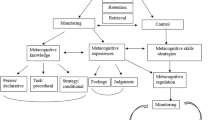

Efklides (2008) detailed metacognitive experiences, metacognitive skills, and metacognitive knowledge as three distinct facets of metacognition. These aspects serve different functions when learners pursue self-regulation. For example, metacognitive experiences and metacognitive knowledge refer to the “monitoring function that informs self-awareness as well as awareness of cognition” (p.280), whereas metacognitive knowledge pertains to one’s ability to understand and manipulate the cognitive processes to control cognition. Metacognition was thus coined a monitoring function and control over cognition. To draw a more complete picture of understanding metacognition in language learning, Teng et al. (2022b) presented a framework on the multi-faceted elements of metacognition. Figure 1 depicts the multifaceted feature of metacognition.

Multi-faceted elements of metacognition (Teng et al., 2022b, p.171)

First, the cognitive processes include at least two interrelated levels, which Nelson (1996) described as the “meta-level” and the “object-level.” The metacognitive system involves a type of dominance relation, involving the flow of information. This flow gives rise to a distinction between “control” and “monitoring” (Nelson, 1996). Acquisition, retention, and retrieval are three stages listed between the two levels. Metacognition is thus a cognitive and conscious process. Learners are consciously aware of the monitoring and control of cognition. Second, the monitoring function covers metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive experiences. At the same time, control of cognition comprises metacognitive skills/strategies. Third, metacognitive experiences and skills direct the learners’ ability to monitor and control their cognitive processes. Such a process can be depicted as metacognitive regulation (e.g., planning, monitoring, evaluating). Reflection is an essential component of the plan-monitor-evaluate process. Finally, metacognition is formed because of the dynamics between metacognitive monitoring and metacognitive control. In addition, metacognitive knowledge, experiences, and skills interact with each other.

Metacognition in EFL writing

Metacognition is an important lens through which writing in a second and foreign language context can be enhanced (Teng, 2019). Metacognition is not just a notion applied in the field of educational psychology. It is receiving increasing attention in the field of teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). Students who are learning English as a second and foreign language are different from those who learn it as L1 because of the linguistic demands of gaining literacy and simultaneously understanding complex content in a new language (Hedgcock, 2012). Researchers have increasingly emphasized the effect metacognition has on EFL learners’ writing outcomes. For example, Qin and Zhang (2019) explored the relationship between EFL students’ metacognitive strategy knowledge and writing performance. The participants were 126 EFL students at a university in China. The results supported the significant correlation between metacognitive strategy knowledge and writing performance. They also emphasized the role of EFL students’ language proficiency. For example, compared to lower proficiency group students, higher proficiency group students demonstrated more use of metacognitive strategies, including planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Bui and Kong (2019) explored metacognitive training in peer review interaction for L2 students. The participants, who were secondary school learners in Hong Kong, received a 12-week intervention course in writing. The results supported the effectiveness of metacognitive training in increasing learners’ engagement and collaboration. The training also provided more opportunities for content-related feedback. A recent article (Teng & Huang, 2021) focused on 352 university EFL students’ development of writing complexity, accuracy, and fluency. The intervention was a 16-week training course incorporating metacognitive training into collaborative writing. The treatment did not yield any positive results on writing complexity and fluency, but it significantly enhanced writing accuracy.

With reference to EFL student writers’ metacognitive awareness, the pivotal role of metacognition in EFL writing was observed (e.g., Zhang & Qin, 2018). For example, Ruan (2014) depicted a threefold metacognition framework – person, task, and strategy variables – based on interview data with EFL students. In terms of person-related variables, student writers demonstrated motivation, self-efficacy, and writing anxiety. Task purposes, task constraints, and cross-language task interference constituted task awareness. Planning, text generating, and revising were part of strategy awareness. Ruan’s (2014) description of the writing knowledge domain reflects Kellogg’s (1994) depiction of metacognitive awareness about the self, tasks, and strategies as part of writing knowledge, as well as Wenden’s (2001) study on task awareness for planning and evaluating writing. As argued by Kellogg (2008), writing poses significant challenges to learners’ memory and thinking cognitive system, for which planning, language generation, reviewing, and the mental representations in working memory “undergo continuous developmental changes through maturation and learning within specific writing tasks” (p. 4). Based on observation of the writing development of EFL student writers, Negretti and McGrath (2018) argued that metacognition, specifically metacognitive knowledge, can be incorporated into the EFL writing classroom. Students were interviewed about how they used genre knowledge for writing. The results showed that metacognitive tasks encouraged students’ conceptualization of genre knowledge for EFL writing. De Silva and Graham (2015) argued that metacognitive knowledge is essential to the writing process for L2 student writers, and they can use metacognitive knowledge to plan, monitor, and evaluate their writing. In a recent study (Teng et al. 2022a), the focus was to validate a newly developed instrument, i.e., the Metacognitive Academic Writing Strategies Questionnaire (MAWSQ). Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) supported a one-factor second-order model of including declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, conditional knowledge, planning, monitoring, evaluating, information management, and debugging strategies. The findings also provided evidence for the significant predicting effects of the eight strategies on EFL academic writing performance. In summary of the above studies, metacognition is multifaceted, and different components of metacognition contribute greatly to EFL students’ writing performance. Although there is not sufficient evidence showing that metacognitive deficits are solely responsible for writing, there is now substantial evidence that many EFL students who are unaware of metacognitive strategies may encounter problems in writing.

Critical thinking skills

Metacognition is thinking about thinking. Research on metacognition reflects a central issue in cognitive development — whether there can be a transfer of metacognitive awareness in thinking skills from one domain of experience to another, and whether this transfer, if it occurs, is part of development in thinking skills. Learners may vary in their ability to think and learn from experience. These individual differences may be related to differences in the use of metacognitive processes. Thus, it is essential to consider critical thinking skills when we discuss the notion of metacognition. Thinking involves different types of thought processes. Researchers have provided increasing evidence for conceptualizing two types of thinking processes and have made significant progress in interpreting their nature and operation (Evans & Stanovich, 2013; Stanovich & Toplak, 2012). For example, Stanovich (1999) may have been the first to distinguish between ‘System 1’ and ‘System 2’ thinking. System 1 was conceptualized as corresponding to intuitive processing, while System 2 was regarded as reflective. Stanovich (2009) later decomposed System 1 into The Autonomous Set of Systems (TASS) of possessing with a fast, automatic, unconscious nature and System 2 into reflective and algorithmic minds. As theorists attempt to synthesize and understand the processes of cognition, researchers tend to agree that an increasingly elaborate set of features should be associated with each type of thinking. Thus, it is not surprising that critical thinking has been conceptualized in various ways. Paul (1995) emphasized the importance of the “logic of language” in human reasoning. This position suggests that thinking is human nature. Paul (1995) mentioned the need to intervene in thinking—to analyze and assess and, when necessary, improve it. Magno (2010) considered critical thinking an outcome of metacognition because critical thinking is formed through the “development and evaluation of arguments and coming up with inferences” (p. 139). Schuster (2019) conceptualized critical thinking as a “commitment to letting logic and reasoning be the driving force in guiding judgment and decision-making, rather than giving in to emotions” (p.86).

The varied conceptualizations suggest the following features: reasoning or logical analysis abilities; inference and problem solving; decision making; expressing opinions; reasoning, predicting, generalizing, and concluding arguments; and building a syllogistic awareness of the hierarchy of cognitive skills and taxonomies of skills. These features collectively reflect an understanding of critical thinking.

Critical thinking skills play a key role in academic instruction, which requires analytical thinking to perform essential functions (Watson & Glaser, 2008). Newman et al. (1995) engaged in content analysis to measure critical thinking under the following two group learning conditions: learning through face-to-face and computer conference seminars. They framed critical thinking as a process with the following five stages: (1) problem identification (skill: elementary clarification); (2) problem definition (skill: in-depth clarification); (3) problem exploration (skill: inference); (4) problem evaluation/applicability (skill: judgment); and (5) problem integration (skill: strategy formation). Based on these stages, critical thinking skills encompass the following five factors: making correct inferences, recognizing assumptions, deducing information, drawing conclusions, and interpreting and evaluating arguments (Table 1). In particular, the focus of critical thinking skills was on the learners’ abilities to recognize problems, seek support for the truth, develop knowledge of valid inferences, make generalizations, and determine different types of evidence (Watson & Glaser, 2008).

Scholars have evaluated the role of critical thinking in depth. For example, Watson and Glaser (2009) adopted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to compare a one-factor model, three-factor model, and five-factor model. The results showed that the five-factor model had the best model fit. Bernard et al. (2008) analyzed the psychometric properties of a critical thinking skills test, i.e., the Watson–Glaser critical thinking test. The authors found that the correlation between the subscales of the test ranged from 0.17 to a peak of 0.40. They argued that critical thinking should focus on “a collection of highly interrelated skills and abilities” because the sub-skills of critical thinking are “not easily divorced from one another, not operating separately, but existing conjointly and complementarily” (p. 20).

Researchers have also delineated the relationship between critical thinking skills and metacognition. For instance, Magno (2010) provided evidence to support a model containing eight metacognition factors and five critical thinking skills factors in comparison to a model including two metacognition factors and five critical thinking skills factors. These findings show that connections exist between metacognition and critical thinking skills. Ku and Ho (2010) investigated the metacognitive component of critical thinking skills of 10 Chinese undergraduates (seven women and three men) at a university in Hong Kong. Participants’ critical thinking abilities were assessed through six thinking tasks, which included hypothesis testing, verbal reasoning, argument analysis, likelihood of understanding, decision-making, and argument analysis. Among 407 coded units, 163 (40%) were coded as metacognitive strategies. In contrast, 70 (25%) out of 276 units in the low-performance group were coded as metacognitive strategies. Metacognitive strategies thus appeared to enable students to monitor and control their thinking processes, showing that a critical thinker can better control his or her thinking processes, and metacognitive strategies facilitate such control.

Some studies have also explored the association between critical thinking skills and academic learning, including writing. D’Alessio, Avolio, and Charles (2019) focused on the effect of critical thinking on university students’ academic performance (N = 1,620 participants). They took an academic performance test that covered business operations, marketing, finance, and strategy and leadership. The results showed that learners’ critical thinking skills were related to their academic performance. In particular, the students’ analysis and interpretation skills were pivotal to the planning process. Their abilities to evaluate arguments, make inferences, and deduce information were correlated with decision-making. Tan et al. (2012) suggested the role of creativity in writing, for which students should “think like writers”. They argued that it is essential to foster multiple components of creative potential in a way that is beneficial to the writing domain. Mehta and Al-Mahrooqi (2015) found that learners who possessed stronger critical thinking skills demonstrated better writing performance. Both oral and written practice helped students improve their critical thinking skills.

Gaps in the literature and rationale for this study

As an extension of the work by Magno (2010) and Halpern (1998), along with other research (Teng et al., 2022b), the current study tested models connecting metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing. The rationale for the present study is as follows. First, metacognition and critical thinking skills are interconnected. The cognitive and metacognitive elements of thinking are clearly identified in Sternberg's (1985) information processing model of the mind. Being a critical thinker demands self-examination and an evaluation of one’s thoughts and beliefs (Ku & Ho, 2010). The metacognitive cycle, which is often conceptualized in a four-stage process of planning, monitoring, evaluating and regulating, is relevant to the critical-thinking process (Magno, 2010). Second, metacognition is related to writing, as indicated by an early model of thinking and speech (Vygotsky, 1987), which states that the process of transitioning from thoughts to words is based on cognitive acts (i.e., deliberately analyzing and processing information and taking action). It is assumed that writing requires a web of meaning linking learners’ prior and present experiences to make information comprehensible. Subsequent models also referred to that pertaining to writing (e.g., Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987; Flower & Hayes, 1980), and writing was framed as a cognitive interactive process. Strategies, such as planning, translating, reviewing, and monitoring, help learners devote consistent effort to writing, which leads to better writing performance (Teng, 2019; Teng & Zhang, 2018). Hence, student writers need “self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions” (Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997, p. 76) to control their writing-related behavior. Metacognition is, thus, a determining factor in writing development. Finally, critical thinking skills are paramount to the possible enhancement of writing (Cottrell, 2017). EFL students’ critical thoughts may be at the same level as their writing development. The hypothesized model that drives the present study is shown in Fig. 2.

However, previous studies have generally overlooked the complex relationships between metacognition, critical thinking skills, and EFL academic writing. It is therefore necessary to further test models of metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing to fill this knowledge gap and to evaluate how metacognition is related to critical thinking, and academic writing. The present study clarifies the factor structure of metacognition, the appropriateness of the Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (W-GCTA) instrument as a measure of critical thinking, and the strength of metacognition as a cognitive skill that may influence writing. This study attempts to answer the following questions:

-

1.

To what extent is metacognition associated with academic writing performance?

-

2.

To what extent is metacognition associated with critical thinking skills?

-

3.

To what extent can metacognition and critical thinking skills predict academic writing performance?

Method

Participants

The study participants consisted of 664 third-year students (363 men and 301 women) at a university in mainland China. The participants were from different majors, including computer, engineering, marketing, management, and communication. All students were EFL learners who spoke Mandarin Chinese as their first language. Their English learning experiences in the first and second years focused on foundation English skills (i.e., listening, reading, writing, and speaking). Participants reported having at least 10 years of experience learning English; however, academic writing in English was new to them. The 664 participants were selected from 752 students across 15 classes. Participants were included if they had no missing responses on the tests and completed all writing exercises. All participants took part in this study voluntarily, and each received a supermarket coupon for completing the research requirements.

Academic writing course

The participants were enrolled in an academic English writing course. This course was intended for non-English major students who had completed the first two years of general English learning courses. The teaching focused on the academic skills, basic elements of academic writing, theoretical knowledge and practical skills essential to the production of texts for interdisciplinary academic discourses. During this course, students practice critical reading and writing by summarizing, analyzing, evaluating and synthesizing ideas, as well as engaging with scholarly sources and incorporating them into their writing. The teachers also teach about the different writing genres, including the argumentative essay genre. The teachers in the course did not teach metacognitive strategies. There were a total of 10 different teachers for the course. Involving different teachers this this course may have affected the participants’ academic writing test outcomes, which is a limitation.

Instrument

Metacognitive Academic Writing Strategies Questionnaire (MAWSQ)

In the present study, metacognition was assessed by means of self-reporting through a questionnaire. Despite criticism that metacognitive strategy use or the execution of metacognitive skills cannot be adequately assessed by means of questionnaires (Veenman & Van Cleef, 2019), questionnaires are still the most common way to assess metacognitive ability (Meijera et al., 2013). To avoid the limitations involved in using a questionnaire, a questionnaire was constructed for assessing metacognition that was designed particularly for students engaged in academic writing in higher education.

The MAWSQ was developed and validated by Teng et al. (2022b). Scale items were generated through interviews with 20 student participants. The questionnaire items were also compared with metacognitive strategy items established in previous studies (Oxford, 2013; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Wolters & Benzon, 2013). The MAWSQ aims to measure metacognitive strategies in academic writing. All items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The instrument includes 43 items, with 13 assessing knowledge of metacognition and 30 assessing regulation of metacognition. The knowledge of metacognition subscale measures the following subfactors: (a) declarative knowledge (DK), (b) procedural knowledge (PK), and (c) conditional knowledge (CK). Regulation of metacognition includes the following processes: (a) planning (P), (b) monitoring (M), (c) evaluating (E), (d) information management (IM), and (e) debugging strategies (DS). The items reflect learners’ awareness and use of metacognitive strategies in academic writing situations. In terms of validation, Teng et al. (2022b) conducted EFA and CFA, furnishing evidence validating the two hypothesized models, i.e., an eight-factor correlated model and a one-factor second-order model. In addition, the model comparison highlighted that the one-factor second-order model was better, as metacognition functions as a higher order construct that correlates the eight metacognitive strategies, as mentioned above. In the present study, the MAWSQ was applied to a different comparable population at a different university.

Cronbach’s alpha values were analyzed to examine the internal consistencies in the survey responses. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the eight strategies ranged from 0.792 to 0.872, which is evidence for the internal consistency of the responses to the items in the present study.

Critical thinking skills

The W-GCTA, which was developed by Watson and Glaser (1980), is adopted to assess learners’ critical thinking skills. The W-GCTA presents students with text sentences to assess various aspects of critical thinking (Mahoney, 2011). The test’s validity and reliability were substantiated in earlier studies (e.g., Moss & Kozdiol, 1991). In particular, the tool measures learners’ application of core critical thinking skills, including making inferences, logical assumptions, and reasoning with supported arguments. The W-GCTA includes exercises in the following five sub-sections: recognizing assumptions, evaluating arguments, conducting deduction, making inferences, and interpreting information. The following five subtests were used to measure interdependent aspects of critical thinking skills, totaling 86 items: (1) evaluation of arguments (EoA, 25 items); (2) recognition of assumptions (RoA, 16 items); (3) deduction (Ded, 25 items); (4) inferences (Inf, 20 items); and (5) interpreting information (Int, 24 items). Appendix II presents sample W-GCTA items.

Factor analytic studies lent support to this instrument’s construct validity and its relationship with academic performance (Watson & Glaser, 2009). The Cronbach’s alpha values for the five sub-scales ranged from 0.792 to 0.865. On this scale, one point is awarded for each correct answer; incorrect answers receive zero points.

Academic writing test

This academic writing test was an institutional standardized test developed by ten English teachers in the English language teaching department. They had experience teaching the participants. Another 15 English lecturers who had not taught the participants were invited to check the items and the content validity. This test evaluated the EFL students’ abilities to paraphrase sentences, write topic sentences, write a thesis statement, and synthesize information during research essay writing. The main focus of this test was on the academic research setting. The learners needed to display linguistic knowledge, critical thinking, and effective organization of ideas on this test. The assessment includes four sections. Section 1 (16 items) asks students to rewrite given sentences using language common in academic writing. In Section 2 (10 items), the students each composed a thesis statement. Each item contained a general subject and a specific subject (e.g., education/distance education), and the participants wrote a thesis statement for each group of words. Section 3 (10 items) instructs students to write topic sentences, with one topic sentence per paragraph. All paragraphs were taken from academic essays. Section 4 focuses on essay writing; the students were required to write an essay of approximately 150 words for a research topic based on the provided information. For example, students were required to synthesize possible reasons after summarizing and comparing different figures and writing down implications based on the findings.

In Sections 1–3, each correct answer was awarded one point, while incorrect answers received zero points. The maximum scores for Sections 1, 2, and 3 were 16, 10, and 10 points, respectively. Partial points were given for sentences containing minor grammatical mistakes. Partial points were also given if a grammatically correct thesis statement or topic sentence was not sufficiently focused. In the final section, i.e., the writing portion, scoring was based on the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) writing rubric covering task achievement (e.g., how appropriately, accurately and relevantly the response fulfils the requirements set out in the task), coherence and cohesion (e.g., the clarity and fluency of the message), lexical resource (e.g., the range of vocabulary the test-takers used and the accuracy and appropriacy of that use), and grammatical range and accuracy (e.g., the range and accurate use of the test-takers’ grammatical resource). The purpose was to assess a learner’s ability to (a) present a solution to a problem; (b) present and justify an opinion; (c) compare and contrast evidence, opinions and implications, and (d) evaluate ideas, evidence or an argument. Each dimension received a maximum of six points for a total of 24 points. The maximum possible score on the entire test was 60 points. As this is an institutional test for all learners, the English language teaching department provided scores for research purposes, including the global score, rather than the scores for each section. Thus, the global score of the writing test was subject to data analysis. Two EFL teachers rated the test in this study. Interrater agreement was satisfactory (percent agreement = 93%; Cohen’s Kappa = 0.89). Differences were resolved based on inter-rater discussion. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the four sections of the academic writing test ranged from 0.812 to 0.868, indicating sound reliability.

Procedures

Participants were asked to complete the MAWSQ and W-GCTA during the last two lessons of the writing course. The questionnaire was distributed at the end of the class to better elicit learners’ awareness of metacognitive strategies and critical thinking. Participants completed the MAWSQ online. The learners completed this survey within 30 min. They then completed a paper-and-pencil version of the W-GCTA within 60 min. The 90-min long academic writing test was administered at a fixed time one week after the end of the course in a paper-and-pencil format. All test instructions were in Chinese to ensure participants’ comprehension.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to examine the data for normal distribution, and Pearson correlation coefficients were used to understand the bi-variate correlations between the variables of interest. Structural equation modeling (SEM), a technique that tests the significant path parameters of variables and analyzes structural relationships, was adopted to answer the research questions. The variables of metacognition and critical thinking were composed from a set of manifest variables in this study. SEM confirmed the validity of the path model for metacognition, academic writing, and critical thinking. The conclusions were based on the following omnibus fit statistics: a chi-square (χ2) statistic; the degrees of freedom (df), p value, and the ratio of chi-square χ2 divided by the df; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). Based on Hu and Bentler (1999), the ratio of chi-square (χ2) divided by the df should be less than 0.30. A good model fit also requires the following: a cutoff value near 0.90 for TLI, GFI, CFI, and NFI; a cutoff close to 0.08 for SRMR; and a cutoff close to 0.05 for RMSEA. The above indicators reflect a relatively good fit between the hypothesized model and observed data.

Results

Descriptive statistics and normality check

Table 2 lists the descriptive statistics for the study sample. The mean scores for the eight factors of metacognition ranged from 4.24 to 4.84, indicating that the learners had developed a certain metacognitive writing strategy level. Standard deviations ranged from 0.96 to 1.07. The skewness values ranged from -0.013 to 0.172; those for kurtosis ranged from 0.166 to 0.627. The mean scores for the five factors of critical thinking ranged from 11.7 to 18.36, suggesting that learners had some knowledge of critical thinking. Standard deviations ranged from 1.57 to 3.26. The skewness values ranged from -0.453 to -0.201, and kurtosis values ranged from -0.738 to 2.156. The mean score on the academic writing test was 37.8 (SD = 3.59), revealing that participants had achieved a certain degree of academic writing performance. The skewness and kurtosis values were -0.177 and 1.098, respectively. The skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the data fit the normality assumption (Kline, 1998).

Correlation results

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation results.

As shown in Table 3, all factors were significantly and positively correlated at the level of 0.001. Thus, the eight sub-categories of metacognition were significantly and positively correlated with each other and with academic writing and various components of critical thinking.

SEM results

The SEM results involved three models. Model 1 tested the relationship between metacognition and academic writing (Research Question 1; Fig. 3); Model 2 tested the relationship between metacognition and critical thinking (Research Question 2; Fig. 4); and Model 3 tested the prediction of academic writing with metacognition and critical thinking (Research Question 3; Fig. 5).

Path from of metacognition to academic writing. Note. DK = Declarative knowledge (5 items); PK = Procedural knowledge (4 items); CK = Conditional knowledge (4 items); P = Planning (7 items); M = Monitoring (6 items); E = Evaluating (7 items); IMS = Information management strategy (5 items); DS = Debugging strategy (5 items)

Path from metacognition to critical thinking. Note. DK = Declarative knowledge; PK = Procedural knowledge; CK = Conditional knowledge; P = Planning; M = Monitoring; E = Evaluating; IMS = Information management strategy; DS = Debugging strategy, Inf = Inference, ROA = Recognition of assumptions, Ded = Deduction, Int = Interpretations, EoA = Evaluation of arguments

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between metacognition and academic writing, where metacognition included eight factors in a structural model. Model 1 (Fig. 3) fit the data well (χ2 = 2618.427, df = 1112, χ2/df = 2.355). The RMSEA indicated a good fit with a value of 0.065. Other goodness-of-fit indices, such as GFI (0.907), SRMR (0.075), CFI (0.917), and TFI (0.904), also showed a rather good fit. All factors related to metacognition had significant paths with parameter values larger than 0.50. In terms of the relationship between metacognition and academic writing, the normalized path coefficient value was 0.885 at a significance level of 0.01 (z = 7.494, p < 0.001). Accordingly, metacognition was significantly and positively related to EFL students’ academic writing after considering measurement error.

Model 2 (Fig. 4) also fit the data well (χ2 = 2618.427, df = 1112, χ2/df = 2.355). RMSEA (0.065) showed a good fit, as did GFI (0.907), SRMR (0.075), CFI (0.917), and TFI (0.904). These values were identical to those in Model 1. All factors relevant to metacognition and critical thinking demonstrated significant paths with parameter values larger than 0.50. The association between metacognition and critical thinking showed a normalized path coefficient of 0.870, which was statistically significant at the 0.001 level (z = 7.193, p < 0.001). Metacognition was therefore significantly and positively associated with EFL students’ critical thinking skills with consideration of error measurement.

Model 3 (Fig. 5) also fit the data (χ2 = 2509.511, df = 1111, χ2/df = 2.259). RMSEA showed a good fit with a value of 0.069, as did GFI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.072, CFI = 0.911, and TFI = 0.914. Again, all factors related to metacognition and critical thinking had significant paths as evidenced by parameter values larger than 0.50. This model demonstrated the prediction of academic writing performance with both metacognition and critical thinking skills. First, metacognition predicted academic writing (normalized path coefficient = 0.896) at a significance level of 0.01 (z = 6.954, p < 0.001). Second, metacognition also predicted critical thinking skills (normalized path coefficient = 0.833) at a 0.01 significance level (z = 6.780, p < 0.001). Finally, critical thinking skills significantly predicted academic writing (normalized path coefficient = 0.912); this path was significant at the 0.01 level (z = 18.446, p < 0.001). Overall, this model confirmed the structural relations between metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing.

Discussion

The present study explored links among metacognition, critical thinking skills, and academic writing via SEM. The results are summarized as follows. First, this study highlighted the potential of metacognition to enhance academic writing performance. Second, this study suggested the role of critical thinking skills in academic writing performance. Finally, the findings documented the dynamic relations between metacognition, thinking skills, and academic writing performance. Overall, university students who had established a level of metacognitive awareness, were more likely to think critically, resulting in better academic writing performance.

The findings evoked consideration of the theoretical and pedagogical connection between the three variables. First, the SEM results revealed structural relations between metacognition and academic writing with an appropriate model fit; i.e., metacognition predicted learners’ academic writing performance. As argued by Schraw and Moshman (1995), metacognition includes a “systematic structure of knowledge that can be used to explain and predict a broad range of empirical phenomena” (p. 356). The current study transferred the metacognitive strategies (i.e., declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, conditional knowledge, planning, monitoring, evaluating, information management strategies, and debugging strategies) described by Schraw and Dennison (1994) to an EFL academic writing context, extending to what has been known in Teng et al. (2022b). In this case, the strategies were significantly correlated with each other, as well as with academic writing performance. Wolters (1999) explained that metacognitive strategies can enhance learners’ “cognitive engagement, overall level of effort, and subsequent achievement within an academic setting” (p. 285). Scholars have further suggested that metacognition helps student writers develop knowledge in “social, motivational, and behavioral processes” (Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997, p. 76). Such knowledge is essential for academic writing. Our results imply that the writing performance of EFL students depends on the use of metacognitive knowledge and regulation strategies, as supported by Bui and Kong (2019) and Teng et al. (2022b). Teng (2019) also contended that metacognitive knowledge (i.e., whether learners can understand critical elements for producing high-quality compositions) and metacognitive regulation (i.e., whether learners can discern self-regulated strategies to manage the dynamic features of composition) are crucial components of EFL essay writing. Academic writing performance is thus conceptualized as a cognitive process related to student writers’ strategic behavior in understanding metacognitive knowledge and monitoring their regulation to communicate ideas and information to the wider academic community. As proposed by Qin and Zhang (2019), learners demonstrating better academic writing performance in a foreign language may possess “metacognitive knowledge of how to evaluate their writing process and weigh their expectations of themselves” (p. 405).

Second, the SEM results showed that the chosen measures of metacognition and critical thinking were adequate given significant parameters and an appropriate fit to the data. In particular, the structural relations between the eight metacognition factors and the five critical thinking factors exhibited an acceptable model fit. Metacognitive awareness significantly increased the variability in learners’ critical thinking skills. Consistent with Ku and Ho (2010), these findings indicate that awareness of knowledge and strategies in planning, monitoring, and evaluating can lead to enhanced critical thinking. Learners’ strengths are in planning “specific steps that guide thinking (high-level planning)” and revising “their approach upon evaluation”, which can also “resolve confusion and improve performance” (Ku & Ho, 2010, p. 263). Our results also substantiate models related to metacognition and critical thinking. The metalevel operations that “come in the form of integrated or separate metacognitive skills” may mediate learners’ critical thinking skills (Magno, 2010, p. 149). Building upon prior studies, improvements in critical thinking require executive control and executive processes that are built by fostering learners’ awareness of metacognition.

In particular, the different sub-factors of metacognition, including DK, PK, CK, P, M, E, IMS, and DS, were positively and significantly correlated with the different sub-factors of critical thinking skills, including Inf, RoA, Ded, Int, and EoA. For instance, the sub-factors of metacognition (e.g., planning or monitoring) may have a significant influence on one’s ability to evaluate arguments effectively (a sub-section of critical thinking skills). Bernard et al. (2008) also argued that the focus of critical thinking should be on a collection of metacognitive skills and abilities. In the present study, the 5 sub-sections should be regarded as a collective set of metacognitive skills and abilities. Hence, although metacognitive knowledge and regulation are commonly used to explain metacognition (Efklides, 2008), it can be argued that metacognition reflects the ability of individuals to identify multiple aspects of metacognitive knowledge and regulation to engage in critical thinking. An awareness of metacognitive skills is fundamental to such thinking skills. Discerning metacognitive skills could help learners achieve critical/higher-order thinking because these skills afford learners opportunities to reflect on metalevel resources that enhance critical thinking.

Finally, the SEM results in this study unveiled structural relations between metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing. The correlation results were close to those of Qin and Zhang (2019), who focused on metacognitive knowledge and writing. Notably, the correlation between metacognition and writing is quite high. In line with D’Alessio et al. (2019), critical thinking skills were found to be very important in academic learning. In particular, our research shows that metacognition and critical thinking skills predict academic writing performance. These findings corroborate Bereiter and Scardemalia’s (1987) proposal regarding the use of knowledge-telling and knowledge-transforming models in writing. More specifically, less experienced student writers tended to restate information, whereas more skilled student writers often engaged in critical thinking and maintained deliberate, strategic control over parts of the cognitive process during writing. Such deliberate control presents possibilities for considering the need to apply one’s thoughts and knowledge when writing. The links among metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing are tied to the nature of those constructs. Metacognitive awareness involves one’s abilities to categorize, select, compare, and contrast different facts and opinions to form judgments (Ruan, 2014). Higher-order thinking skills used in recognizing problems and discerning truthful evidence emerge through cognitive processes as students follow logical steps to navigate language-learning tasks and judge their learning behaviors while monitoring, evaluating, and reflecting on learning outcomes (Phakiti, 2018). Writing development is also connected to learners’ metacognition regarding activities or growth (Camp, 2012), as well as to critical thinking skills (Mehta & Al-Mahrooqi, 2015). The overlap between these three constructs results in the clear integration in a model.

In the present study, the apparent links between metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing clarify three theoretical directions. First, the multiplicity of metacognition operates as an executive process, helping learners attain higher-order thinking skills, e.g., critical thinking. Critical thinking calls for conscious adaptation of metacognitive strategies. Second, the identified metacognitive skills serve as executive functions that help learners manage writing tasks by making inferences, recognizing assumptions, making deductions, interpreting information, and evaluating arguments. Third, academic writing requires learners to be highly capable of reflecting on their metacognitive control and available cognitive strategies when learning to write.

Limitations and implications

This study has some limitations. First, in future research should include more metacognition items to reflect the multifaceted nature of metacognition. Second, assessing metacognition using a self-report questionnaire may not fully reveal learners’ metacognition. The use of questionnaires may only assess what students subjectively perceive their knowledge and actions to be. Third, the establishment of thinking skills is multifaceted, and different tests may be needed to compare learners’ development. In addition, the correlation between critical thinking and writing performance may be influenced by task commonalities. For example, critical thinking might be embedded in the assessment of writing performance, leading to high correlations between W-GCTA and writing performance. Fourth, the academic writing test may not reflect the various demands in the academic writing setting and may not fully represent the ability of learners engaged in academic writing outside of the test environment. Finally, subsequent research should examine metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing performance from a longitudinal perspective.

Despite these limitations, this study provides meaningful implications related to metacognition, critical thinking, and academic writing. First, metacognition and critical thinking can be conceptualized as containing multiple factors. Our findings offer a way to conceptualize metacognition as a skills facet. Prior definitions of metacognition focused either on strategies and self-knowledge for learning and performance (Pintrich, 2002) or on metacognitive knowledge, regulation, and experiences (Efklides, 2008). Theoretically, metacognition can be considered a cognitive process of thinking critically about different components, perspectives, and views related to cognitive acts. Second, identifying metacognitive skills has pedagogical implications for teaching and learning. Learners need instruction on how to develop metacognitive awareness. Teachers need to cultivate EFL student writers’ abilities to reflect on, monitor, and evaluate their learning strategies so that they may become more self-reliant, flexible, and productive when engaged in academic writing. Cultivating learners’ higher-order thinking skills in academic writing not only requires the teaching of linguistic structures but also guidance in helping learners recognize their own cognitive growth. Teachers can create a classroom culture of reflexivity by encouraging dialog that engages learners in academic writing. Another skill that requires direct instruction is critical thinking, which is a means to draw conclusions or make a judgment. Teachers can focus on at least the following four areas for instructing critical thinking: familiarizing students with the writing topic, enhancing intra-group problem solving by fostering interactions with group members, improving inter-group problem solving by organizing between-group cooperation, and maximizing independent problem-solving skills for academic writing. Finally, metacognition can be applied to promote learners’ critical thinking abilities. That is, metacognition and critical thinking potentially facilitate academic writing. Furthermore, to reinforce the role of metacognition in promoting critical thinking, it is essential to assess how successful individuals think critically. This study highlights the potential when considering the connection between metacognition, critical thinking, and EFL academic writing.

References

Atkinson, D. (1997). A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL Quartely, 31, 71–94.

Atkinson, D., & Ramanathan, V. (1995). Cultures of writing: An ethnographic comparison of Ll and L2 university writing language programs. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 539–568.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Erlbaum.

Bernard, R. M., Zhang, D., Abrami, P. C., Sicoly, F., Borokhovski, E., & Surkes, M. A. (2008). Exploring the structure of the watson–glaser critical thinking appraisal: One scale or many subscales? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3, 15–22.

Bui, G., & Kong, A. (2019). Metacognitive instruction for peer review interaction in L2 writing. Journal of Writing Research, 11(2), 357–392.

Camp, H. (2012). The psychology of writing development—and its implications for assessment. Assessing Writing, 17(2), 92–105.

Chaffee, J. (2015). Critical thinking, thoughtful writing (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Cottrell, S. (2017). Critical thinking skills: Effective analysis, argument and reflection. Bloomsbury Publishing.

D’Alessio, F., Avolio, B., & Charles, V. (2019). Studying the impact of critical thinking on the academic performance of executive MBA students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 275–283.

De Silva, R., & Graham, S. (2015). The effects of strategy instruction on writing strategy use for students of different proficiency levels. System, 53, 47–59.

Efklides, A. (2001). Metacognitive experiences in problem solving: Metacognition, motivation, and self-regulation. In A. Efklides, J. Kuhl, & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Trends and prospects in motivation research (pp. 297–323). Kluwer.

Efklides, A. (2006). Metacognition and affect: What can metacognitive experiences tell us about the learning process? Educational Research Review, 1, 3–14.

Efklides, A. (2008). Metacognition: Defining its facets and levels of functioning in relation to self-regulation and co-regulation. European Psychologist, 13, 277–287.

Efklides, A., Niemivirta, M., & Yamauchi, H. (2003). Motivation and self-regulation: Processes involved and context effects—A discussion. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient, 46, 38–52.

Evans, J St. .B. T., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual-process theories of higher cognition: advancing the debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 223–241.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new era of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906–911.

Flavell, J. H. (2004). Theory-of-Mind development: Retrospect and prospect. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50, 274–290.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1980). The dynamics of composing: Making plans and juggling constraints. In L. Gregg & E. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 31–50). Erlbaum.

Gammil, D. (2006). Learning the write way. The Reading Teacher, 59(8), 754–762.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35, 3–12.

Graham, S. (2006). Writing. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.,), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 457–478). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hacker, D. J., Keener, M. C., & Kircher, J. C. (2009). Writing is applied metacognition. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 154–172). Routledge.

Hall, N. C., & Goetz, T. (Eds.). (2013). Emotion, motivation, and self-regulation: A handbook for teachers. Bingley.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist, 53(4), 449–455.

Harris, K. R., Santangelo, T., & Graham, S. (2010). Metacognition and strategies instruction in writing. In H. S. Waters & W. Schneider (Eds.), Metacognition, strategy use, and instruction (pp. 226–256). The Guilford Press.

Hedgcock, J. S. (2012). Second language writing processes among adolescent and adult learners. In E. L. Grigorenko, E. Mambrino, & D. D. Preiss (Eds.), Writing a mosaic of new perspectives (pp. 221–239). Psychology Press.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Jacobs, J. E., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Children's metacognition about reading: Issues in definition, measurement, and instruction. Educational Psychologist, 22(3-4), 255–278.

Kellogg, R. T. (1994). The psychology of writing. Oxford University Press.

Kellogg, R. T. (2008). Training writing skills: A cognitive developmental perspective. Journal of Writing Research, 1(1), 1–26.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Methodology in the social sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Ku, K. Y. L., & Ho, I. T. (2010). Metacognitive strategies that enhance critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5, 251–267.

Magno, C. (2010). The role of metacognitive skills in developing critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5, 137–156.

Mahoney, B. (2011). Critical thinking in psychology: Personality and individual differences. Learning Matters.

McCormick, C. B. (2003). Metacognition and learning. In W. M. Reynolds & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 79–102). John Wiley & Sons.

Mehta, S. R., & Al-Mahrooqi, R. (2015). Can thinking be taught? Linking critical thinking and writing in an EFL context. RELC Journal, 46, 23–36.

Meijera, J., Sleegersb, P., Elshout-Mohra, M., van Daalen-Kapteijnsa, M., Meeusc, W., & Tempelaar, D. (2013). The development of a questionnaire on metacognition for students in higher education. Education Research, 55, 31–52.

Moss, P. A., & Kozdiol, S. M. (1991). Investigating the validity of a locally developed critical thinking test. Educational Measurement Issues and Practice, 10(3), 17–22.

Negretti, R., & McGrath, L. (2018). Scaffolding genre knowledge and metacognition: Insights from an L2 doctoral research writing course. Journal of Second Language Writing, 40, 12–31.

Nelson, T. O. (1996). Consciousness and metacognition. American Psychologist, 51, 102–116.

Newman, D. R., Webb, B., & Cochrane, C. (1995). A content analysis method to measure critical thinking in face-to-face and computer supported group learning. Interpersonal Computing and Technology, 3(2), 56–77.

Oxford, R. L. (2013). Teaching and researching language learning strategies (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Ozarska, M. (2008). Some suggestions for academic writing instruction at English teacher training colleges. English Teaching Forum, 48, 30–33.

Pally, M. (2001). Skills development in 'sustained' contentbased curricula: Case studies in analytical/critical thinking and academic writing. Language and Education, 15(4), 279–305.

Paul, R. (1995). What every student needs to survive in a rapidly changing world. The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Phakiti, A. (2018). Assessing higher-order thinking skills in language learning. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–7). Wiley.

Pintrich, P. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 219–225.

Pintrich, P. R., Wolters, C. A., & Baxter, G. P. (2000). Assessing metacognition and self-regulated learning. In J. C. Impara, G. Schraw, & J. C. Impara (Eds.), Issues in the measurement of metacognition (pp. 43–97). University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Puustinen, M., & Pulkkinen, L. (2001). Models of Self-regulated learning: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 45, 269–286.

Qin, L. M., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). English as a foreign language writers’ metacognitive strategy knowledge of writing and their working performance in multimedia environments. Journal of Writing Research, 12(2), 393–413.

Ramanathan, V., & Atkinson, D. (1999). Individualism, academic writing, and ESL writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8, 45–75.

Ruan, Z. (2014). Metacognitive awareness of EFL student writers in a Chinese ELT context. Language Awareness, 23(1–2), 76–91.

Sato, M. (2022). Metacognition. In S. Li, P. Hiver & M. Papi (eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and individual differences (95–108). Routledge.

Schoenfeld, A. (1987). What's all the fuss about metacognition. In Schoen- feld, A. (Ed.) Cognitive science and mathematics education (pp.189–215). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schraw, G. A. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26, 113–125.

Schraw, G. A. (2001). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. In H. J. Hartman (Ed.), Metacognition in learning and instruction: Theory, research and practice (pp. 3–16). Springer.

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 460–475.

Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351–371.

Schroyens, W. (2005). Knowledge and thought: An introduction to critical thinking. Experimental Psychology, 52(2), 163–164.

Schuster, S. (2019). The critical thinker: The path to better problem solving, accurate decision making, and self-disciplined thinking. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Shimamura, A. P. (2000). Toward a cognitive neuroscience of metacognition. Consciousness and Cognition, 9, 313–323.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: Critical teaching for social change. University of Chicago Press.

Stanovich, K. E. (1999). Who is rational? Studies of individual differences in reasoning. Elrbaum.

Stanovich, K. E., & Toplak, M. E. (2012). Defining features versus incidental correlates of Type 1 and Type 2 processing. Mind & Society, 11, 3–13.

Stanovich, K. E. (2009). Distinguishing the reflective, algorithmic, and autonomous minds: Is it time for a tri-process theory? In J. St. B. T. Evans & K. Frankish (Eds.), In two minds: Dual processes and beyond (pp.55–88). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sternberg, R. (1985). Approaches to intelligence. In S. F. Chipman, J. W. Segal & R. Glaser, (Eds.) Thinking and learning skills (Vol.2). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tan, M., Randi, J., Barbot, B., Levenson, C., Friedlaender, L. K., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2012). Seeing, connecting, writing: Developing creativity and narrative writing in children. In E. L. Grigorenko, E. Mambrino, & D. Preiss (Eds.), Writing: A mosaic of new perspectives (pp. 275–291). Psychology Press.

Teng, F. (2016). Immediate and delayed effects of embedded metacognitive instruction on Chinese EFL students’ English writing and regulation of cognition. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 22, 289–302.

Teng, F. (2019). The role of metacognitive knowledge and regulation in mediating university EFL learners’ writing performance. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2019.1615493

Teng, F. (2021). Interactive-whiteboard-technology-supported collaborative writing: Writing achievement, metacognitive activities, and co-regulation patterns. System, 97, 102426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102426

Teng, F., & Huang, J. (2019). Predictive effects of writing strategies for self-regulated learning on secondary school learners’ EFL writing proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 53, 232–247.

Teng, F., & Huang, J. (2021). The effects of incorporating metacognitive strategies instruction into collaborative writing on writing complexity, accuracy, and fluency. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1982675

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2018). Effects of motivational regulation strategies on writing performance: A mediation model of self-regulated learning of writing in English as a second/foreign language. Metacognition and Learning, 13, 213–240.

Teng, F., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Development of children’s metacognitive knowledge, and reading and writing proficiency in English as a foreign language: Longitudinal data using multilevel models. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(4), 1202–1230.

Teng, F., Wang, C., & Zhang, L. J. (2022a). Assessing self-regulatory writing strategies and their predictive effects on young EFL learners’ writing performance. Assessing Writing, 51, 100573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2021.100573

Teng, F., Qin, C., & Wang, C. (2022b). Validation of metacognitive academic writing strategies and the predictive effects on academic writing performance in a foreign language context. Metacognition and Learning, 17, 167–190.

Troia, G. A., Harbaugh, A. G., Shankland, R. K., Wolbers, K. A., & Lawrence, A. M. (2013). Relationships between writing motivation, writing activity, and writing performance: Effects of grade, sex, and ability. Reading and Writing, 26, 17–44.

Veenman, M. V. J., & Elshout, J. J. (1999). Changes in the relation between cognitive and metacognitive skills during the acquisition of expertise. European Journal of Psychology of Education, XIV, 509–523.

Veenman, M. V. J., & Van Cleef, D. (2019). Measuring metacognitive skills for mathematics: Students’ self-reports vs. on-line assessment methods. ZDM International Journal on Mathematics Education, 51, 691–701.

Veenman, M. V. J., van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M., & Afflerbach, P. (2006). Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacognition and Learning, 1, 3–14.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R.W. Rieber & A.S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky, Volume 1: Problems of general psychology (pp. 39–285). Plenum Press.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (1980). Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal. Psychological Corp.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (2008). Watson-glaser critical thinking appraisal: Short form manual. Pearson.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (2009). Watson-glaser II critical thinking appraisal: Technical manual and user’s guide. Pearson.

Wenden, A. L. (1998). Metacognitive knowledge and language learning. Applied Linguistics, 19, 515–537.

Wenden, A. (2001). Metacognitive knowledge in SLA: The neglected variable. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research (pp. 44–64). Harlow: Pearson Education

Wolters, C. A. (1999). The relation between high school students’ motivational regulation and their use of learning strategies, effort, and classroom performance. Learning & Individual Differences, 11, 281–299.

Wolters, C. A., & Benzon, M. B. (2013). Assessing and predicting college students’ use of strategies for the self-regulation of motivation. Journal of Experimental Education, 81, 199–221.

Woodrow, L. (2011). College English writing affect: Self efficacy and anxiety. System, 39, 510–522.

Zhang, L. J., & Qin, T. L. (2018). Validating a questionnaire on EFL writers’ metacognitive awareness of writing strategies in multimedia environments. In A. Haukås, C. Bjørke, & Dypedahl, M. (Eds.), Metacognition in language learning and teaching (pp. 157–179). London, England: Routledge.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22, 73–101.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Project from the Education Department of Hainan Province (Project number: Hnky2020ZD-9). We appreciate Professor Chuang Wang’ help in proofreading this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This article involves human participants performed by the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Teng, M.F., Yue, M. Metacognitive writing strategies, critical thinking skills, and academic writing performance: A structural equation modeling approach. Metacognition Learning 18, 237–260 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09328-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09328-5