Abstract

The objective of this study is to identify factors for poor performance and failure faced by small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and to investigate a potential bias between real causes and attribution for stranding. In order to achieve this objective, we have adopted entrepreneurial personal story explorations in eight Portuguese SME. Our research reveals that the most important factors are limited access to finance, poor market conditions, inadequate staff, and lack of institutional support, as well as co-operation and networking. Hereby, at a first glance, external factors were more often cited, but qualitative analysis revealed that internal factors are imminent and not satisfactorily recognized. Even though some owner–managers showed a certain awareness regarding their internal weaknesses, many problems such as lacking strategy and vision, low educational levels, and inadequate social capital are not sufficiently recognized. Therewith, we found a strong attribution error when SME owner–managers judge the causes of their ventures’ unsuccessful performance and failure. Finally, we draw conclusions and suggestions for policymakers, small business owners, consultants, and researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) are of utmost importance for the economy. On the one hand, this alone is true in quantitative terms. In the European Union (EU), more than 99% of the existing firms are SME; they stand for two-thirds of all employment possibilities and account for 60% of value added (ENSR 2003). On the other hand, for a variety of qualitative reasons, SME are economically and socially significant. They are not only seen as a main driver for generating employment, they also promote innovation, put business ideas into practice, foster regional economic integration, and maintain social stability (ENSR 2003). The high figures of SME inject economic variety (Hannan and Freeman 1989) and generate competition, positive for economic output (Porter 1990). Furthermore, SME often occupy niche markets in a very flexible and tailored manner. In fact, features such as flexibility, innovativeness, and problem-solving orientation are considered as key factors for SME success (Lin 1998).

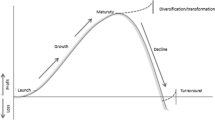

In spite of these facts, over a long period of time, policy-makers paid much attention to large enterprises, and SME were simply neglected in the public and academic focus. Only at the beginning of the 1990s, specific strategies and improvement of economic conditions for SME became a subject; meanwhile they rank high on the political agenda. Recently, much has been done to improve the environment for SME. A series of particular and appropriate legislation has been introduced to try to support growth and stability of SME and to redress the difficulties they face. This seems to be mandatory, since research indicates that failure of SME is high, above all within the first years after starting. Timmons (1994) shows that over 20% of new ventures fail within one year and 66% within six years. Other scholars like Paffenholz (1998) and Woywode (1998) state that approximately 50% of small start-ups survive for more than five years.

Given that such a large percentage of SME is unsuccessful, it is meaningful to investigate the causes of poor performance and failure faced by these firms. According to Storey (1994), the failure of SME is a vitally important area for research and he rightly states that no policy can be formulated for SME without a central understanding of business malfunction’s significance. This comprises the identification of major problems that are assumed to discourage and obstacle SME performance. Much research has been done about success and growth factors of new firms (e.g. Barber et al. 1989; Brüderl et al. 1992, 1996; Audretsch 1995; Audretsch and Mahmood 1995; Gatewood et al. 1995; Almus and Nerlinger 1999; Dowling 2003; van Praag 2003; Kakati 2003; Hemer et al. 2006; García-Muiña and Navas-López 2007). In contrast, little has been done to examine factors of poor performance and failure of established SME, more than ever in European regional contexts. Among the few examples for the latter there are ENSR (2003) and Gallup Organization (2007).

Against this background, the objective of our paper is to identify the factors for unsuccessful performance and failure of SME. Moreover, our intention is to investigate a potential bias between the perceived and real causes, i.e. to explore whether the causal attributions made by SME owner–managers about their ventures’ failure are diverging from the actual causes’ loci. Therefore, we refer to attribution theory (Heider 1958; Kelley 1967; and Weiner 1979, 1985), a social psychology construct to explain certain behaviors and reactions of SME owner–managers. Albeit attribution theory have become integrated into many aspects of psychology, their application to organizational psychology (e.g. Kent and Martinko 1995; Martinko 1995; Weiner 1995) or entrepreneurship and small business (e.g. Zacharakis et al. 1999, Tang et al. 2008) has only received limited attention and is a much more recent phenomenon.

Given the exploratory character of this study and our research objective, we adopt qualitative research, which is gaining acceptance in the small business and entrepreneurship research community (Perren and Ram 2004). As attribution theory builds up on the subjectivity of individuals’ perceptions; accordingly, we apply ‘entrepreneurial personal story explorations’ as the appropriate research methodology. Herein, our research has the SME owner–manager as the primary unit of analysis and was performed in the Portuguese context.

The article is organized as follows. Next section gives a theoretical overview about the main factors for poor performance and failure of SME and demonstrates that attribution theory provides a useful framework to explain the failure attribution bias. “Methodology and data”, based on a qualitative approach, presents methodology and data from eight cases of unsuccessful SME studied in Portugal. “Findings and discussion” exposes and discusses the explorative findings, paying special attention to external and internal factors. Finally, “Conclusions, implications, and limitations” concludes, puts forward suggestions for policy-makers, SME owners, supporting institutions, and researchers, and presents some limitations of the study.

Theoretical framework

Failure factors in SME

Small business literature identifies a huge range of SME success and failure factors. Hereby, one of the most important problems concerns liquidity constraints. Financial capital is convertible into other types of resources and, for that reason, the most general kind and the basis of other resources (Dollinger 1999). Obtaining equity and debt financing seem to be two of the major difficulties SME face and impose severe restrictions on their development (Storey 1994; Winborg and Landström 2001; Brown et al. 2005).

Strongly linked with liquidity constraints, lacking innovative capacity also affects SME development. From the resource-based view, the survival and performance of a firm strongly depends upon the ability to obtain distinctive capabilities that lead to competitive advantages (Barney 1991). This implies the implementation of research and access to external knowledge and technology in order to develop firm-specific assets. Empirical literature has proven that the extent of innovative activities influences firm survival positively (Audretsch 1991, 1995; Audretsch and Mahmood 1995). Moreover, technology-orientation also leads to higher survival rates compared with firms in other sectors (Westhead and Cowling 1995).

The constraints on financial capital and lacking innovative activities severely affect SME competitiveness. At the industry level, several studies, for example those of Audretsch (1991, 1995), Audretsch and Mahmood (1995), Wagner (1994), Agarwal and Gort (1996), and Mata and Portugal (2002), point out the main determinants of competitiveness and survival. These comprise market growth and concentration, economies of scale, as well as barriers to entry. Furthermore, limited access to public contracts and subcontracts, often because of cumbersome bidding procedures and lack of information, inhibit participation in these markets. Also, inefficient distribution channels and their control by larger firms pose important limitations to market access for SME. In fact, Gallup Organization (2007) states that competition for SME in EU has intensified over the last years and that limited purchasing power of customers is the most important business constraint.

For corporate performance in general, contacts, networks, and co-operation are key determinants. The relationship between networking capability and success has been intensively studied in small business literature. Scholars like Birley (1985), Aldrich et al. (1987), Pennings et al. (1998), or Lechner and Dowling (2003) have empirically proved that higher levels of networking activities or social capital are associated with greater firm performance. However, due to firm size, regional-limited operating range, and owner-focused management, an inadequate social capital and therewith lack of co-operation and networking is likely to impose severe constraints for SME.

Furthermore, human resources are a chief factor for a firm’s development. Teece (1998) says that the tacit knowledge, embodied in human beings, is a unique source for firm-specific assets. Indeed, apart from financial aspects, the quality of human capital and effective recruitment of appropriate workforce has proved to be one of the main success and survival factors (Bosworth 1989; Brüderl et al. 1992, 1996; Mata and Portugal 2002).

Hand in hand with the difficulties in recruiting qualified staff before-mentioned, qualifications and experience of SME founders or managers itself often causes severe constraints on SME’s development. In general, the argument that firms founded or managed by individuals with greater human capital perform better than other firms has been extensively scrutinized and corroborated by literature, examples are those of Bates (1990), Brüderl et al. (1992), Storey (1994), Pennings et al. (1998), Van Praag and Cramer (2001), and Van Praag (2003). Research clearly indicates that formal qualifications are positively associated with small firm’s success (Westhead and Cowling 1995; Brüderl and Preisendörfer 2000; Bates 2005).

Along with insufficient qualification and experience of SME managers and often a consequence of that factor, there may occur deficiencies in management. Scholars like Brüderl and Preisendörfer (2000) pointed out the importance of organizational strategies for business growth. Jennings and Beaver (1997) stress that strategic management in SME is unique and cannot be compared with professional management in larger organizations. Furthermore, they state that the reasons for failure or poor performance are due to the multiplicity of roles expected of owner–managers.

Another barrier for SME survival and development seems to be the lack of institutional support, along with inadequate legislation and excessive regulations. Many SME managers complain about the bureaucratic processes that come along with these hindrances; furthermore, they find many services inadequate. Gallup Organization (2007) emphasizes that nearly half of SME in EU consider themselves as operating in an over-regulated environment and detect administrative regulations as the most important business constraint. What aggravates this situation is the scarce awareness, absence of information and time to take advantage of existing support. In addition, Ghobadian and Galler (1996) refer that SME are usually sceptical of outside help.

To sum up, the literature review reveals a series of constraints and failure factors SME face. In order to classify them, Storey (1994) asserts that there are both endogenous and exogenous factors causing small firms’ failure, and their relative significance will depend on the posture and composition of the firm and the prevailing characteristics of the operating environment. Here, we follow Zacharakis et al. (1999) who mentions SME failure factors to be a result of a combination of internal and external determinants. In doing so, we consider external factors as acting upon the firm from outside, and firms are hardly able to abscond from them. Contrariwise, internal factors can be controlled by the firm or its members themselves.

However, in pondering the relative significance of these internal and external factors for a firm’s poor performance and failure, reality and individual perception might be different. Due to specific traits of founder-managers, such as overconfidence (Forbes 2005), it is likely that, when asked about what kind of hindrance caused failure, a perceptual bias would result. To understand certain reactions and allocation of blame, a deeper analysis of this process is appropriate. In this, we think that attribution theory is a promising tool, exposed in the following section.

Attribution theory

As stated before, the origins of poor performance and failure of SME have various rootcauses. However, what individuals judge to be the underlying cause of events does not always correspond to the real situation. Perception of failure is a subjective phenomenon and, thus, frequently biased or in error. In this context, a research area that explains how people perceive circumstances and make judgments about problems is to be related to attribution theory. This social psychology construct was mainly developed by Heider (1958), Kelley (1967) and Weiner (1979, 1985). For Kelley (1967), attribution relates to the process through which individuals deduce or perceive the causes of events, the behavior of others, or the dispositional properties of any entity in the environment. Herein, through affective and cognitive reactions, people search for causes in a variety of domains, and typically either within themselves or within their environment. In this study, attribution theory plays an important role in explaining the failure factors that SME owner–managers perceive and judge.

Scholars have classified these causal attributions along various attributional dimensions. Within the several dimensions proposed by Weiner (1979, 1985), the locus of causality appears to be the most widely accepted, and for our purposes the most important aspect. This approach is based on a backward-looking perspective and distinguishes whether the cause is respectively internal or external. Therewith, it refers to whether individuals believe the cause of a particular outcome resides within or outside them (Tang et al. 2008). As such, the locus of causality differentiates if the event’s cause can be linked to the actor or rather associated to the specific situation (McAuley et al. 1992). Linked with this concept, attributional style refers to the systematic way by which people try to explain their own successes and failures (Kent and Martinko 1995). In doing so, psychologists like Fiske and Taylor (1991) found that a quantity of people usually activate a particular behavior, a so-called ‘chronic schema’, regardless of its appropriateness to the moment.

In this sense, the attribution theory predicts that individuals are likely to ascribe their failures or mistakes to external causes (Bettman and Weitz 1983; Davis and Gardner 2004), attributing causes to situational factors rather than blaming themselves. Then again, other people’s failures are habitually attributed to internal causes, arguing that it is due to their internal personality factors. Fiske and Taylor (1991:73) underpin “the fundamental attribution error is to attribute another’s behavior to dispositional qualities, rather than to situational factors”. For the opposite, individuals tend to attribute their own problems to situational factors. Moreover, literature highlights that attributions may be self-serving or hedonic, as unfavorable outcomes are typically attributed to external forces (Miller and Ross 1975; Zuckerman 1979). In other words, people prefer to be a victim of circumstance rather than of their own doing (Zacharakis et al. 1999).

When analyzing internal and external causes, it was Heider (1958) who firstly described the key socio-psychological components. In his view, internal determinants include ability and effort, whereas the main external factors are task difficulty and luck. Again, Weiner’s (1979) taxonomy comprises ability and motivation as internal, and difficulty and luck as external causes. Hereby, Weiner (1979, 1985) showed that internally attributed failures are particularly important for feelings of shame or dissatisfaction.

Applied to the small business context, Tang et al. (2008) combined both models and generated two attributional styles of entrepreneurs: (1) an internal attributional style depending on causes such as ability and effort and (2) an external attributional style based on task difficulty and luck. For our attributional analysis, we also follow Heider’s (1958) and Weiner’s (1979) taxonomies, bearing in mind the failure factors stated before while adding a few specific elements. We consider ability, social skills, and knowledge to be internal causes, stemming from the inside of the individual. In contrast, we regard market conditions, institutional support, and luck to be external causes, originating from the environment. Overall, we believe that SME owner–managers will attribute their difficulties more likely to external factors, arguing that the causes of failure were market forces rather than poor management. In the same vein, Zacharakis et al. (1999) argued that entrepreneurs are predisposed to attribute the current negative outcomes to external factors.

In sum, the attribution theory is an interesting framework and has significant implications for SME failure analysis. Hence, in our study, this concept plays an important role in explaining the cognitive processes that SME owner–managers go through when they judge the reasons for their ventures’ poor performance and failure. However, studying failed ventures is a difficult undertaking, not at least because it is hard to gather data once a firm has failed. Therefore, we chose to perform a qualitative investigation of a sample of selected SME. The following section presents the methodology and data used in this research.

Methodology and data

Type of approach and research design

Given the exploratory character of this study and our research objective, we adopt qualitative research to examine factors for poor performance and failure in SME. Case studies are recommended when the social and personal context is of fundamental importance for the understanding and interpretation of the phenomena (Yin 1989; Newman 1994). In particular, a multiple holistic design is suitable (Yin 1989), since several cases are to be analyzed.

As noted by Perren and Ram (2004), qualitative methods have been gaining acceptance in the small business and entrepreneurship research community. As attribution theory stresses the subjective aspects of the individuals’ perceptions; consequently, ‘entrepreneurial personal story explorations’ appears to be the appropriate research strategy for the inquiry. According to Perren and Ram (2004), this approach focuses on the individuals’ interpretation of events, recognizing that it is only one subjective dimension amongst the many different accounts from social actors sharing the world. In the same vein, Cope and Watts (2000) also favor voluntaristic and subjective explanations, referring to the individuals’ reasons attributing criticality to certain events.

The distinguishing feature of entrepreneurial personal story exploration lies in privileging the subjectivity of the individuals’ experience (Perren and Ram 2004). For this reason, we focus on the approach of assigning a SME founder respectively SME owner–manager to embody the primary unit of analysis. Moreover, as Chetty (1996), Grant and Perren (2002), and Perren and Ram (2004) state, topics such as survival, development, and growth of SME cannot be understood without analyzing and understanding the relationship between above mentioned factors and the environment in which the business person is embedded.

The research design was conducted by a set of steps. First, we developed the theoretical framework from the literature review. Second, we used this theory to create the appropriate data collecting, as well as a mechanism for analyzing the empirical evidence and findings. In this phase, according to Yin (1989), there is a continuous interaction between the theoretical issues studied and the data collected. Finally, we interpreted the findings in terms of the data collected in the field research. However, as Yin (1989: 35) alerts, “there is no precise way of setting the criteria for interpreting these types of findings”; each researcher can create his or her own criteria.

Cases selection and data collecting

Since our research targets concentrates on unsuccessful SME, the Portuguese reality is an adequate laboratory for our research. On the one hand, the economic structure in Portugal is mainly composed of SME, i.e. 99.0% of the firms are small and medium sized (IAPMEI 2004). On the other hand, their failure rate is high: in the manufacturing sector, 20% of them fail in the first year only and merely 50% make it to year four (Mata and Portugal 1994). More recent studies indicate that over 20% of new ventures do not survive the first year, and one third fail within three years (CIEBI 2005).

The individual entrepreneurial stories for the present study were selected from the convenience sample method (Patton 1990). The task was to choose SME that would have less successful activities, poor performance, and tendency to fail. In Portugal, unsuccessful business stories of varying degrees are not frequently reported in national or local papers and magazines. The selection of stories was, therefore, primarily determined by personal contacts to SME owner–managers, in order to gain trustworthy information about the real situation of their businesses. Based on these insights, we undertook an exemplary selection of eight SME which face poor outcomes in terms of business performance, such as low sales amounts or growth level.

Our data collection consisted of personal interviews, direct observation made through on-site visits, and document analysis. According to Yin (1989) and Patton (1990), these sources of evidence can be the focus of data collection for individual case stories. The majority of the data was collected from interviews, which were conducted using semi-structured questionnaires as a guide. They included questions about the firms in order to obtain key figures and facts, the owner–managers’ characteristics and attitudes, the main determinants for poor performance and failure in the development of his/her business, and the owners’ perceptions about the main obstacles in their firms.

However, even when the person responsible was identified, we noticed that he or she was often hesitant to discuss his or her failure factors. This phenomenon was also described by Bruno et al. (1986), studying failure patterns among high-technology firms. Therefore, in addition to the interviews, we exploited secondary data sources to verify the statements and to obtain supplementary information. Such multiple-data collection allows conducting a more thorough examination of each firm. Herein, document analysis was considered for data triangulation (Denzin and Lincoln 1994) and for larger construct validity (Yin 1989). The documental analysis we performed embraced all types of documents provided by the firms or that were available at the public domain, such as the firms’ website, annual reports, product descriptions, customer and supplier catalogues, as well as other documents.

The interviews were run from March to May 2006, and lasted on average two hours each. In all cases, the respondent was the founder (or one of the founders) of the firm. Thus, the units of analysis were SME and the respective owner–managers.

Firm and interviewees characteristics

With reference to above, the data reported in this work were based on eight SME. Table 1 presents a profile of these cases. As shown, the sample is composed of firms with some diversity within the industry, mainly acting in engineering and manufacturing. While one firm was founded several years ago, the majority (five of them) had been in business for less than five years. As for the year of failure, all firms stopped their business activities within the range of 2003 to 2006.

According to European Commission Recommendation (2003/361/EC), in terms of headcounts as the main criterion, four firms (1, 2, 4, and 5) were micro enterprises, employing fewer than ten people, whereas three (3, 6, and 8) belonged to the small enterprises category, and one (7) was a medium-sized enterprise. When considering the turnover measure, only one firm (5) fulfilled the micro enterprise criterion, while all the others fitted into the small enterprise classification.

Regarding their juridical form (legal status), S Corporation (Sociedade por Quotas) was more representative (seven firms). S Corporation is different from Corporations (Sociedade Anónima) due to the limited capital permitted by law (5.000 Euros contrasted to 50.000 Euros) and the minimum number of partners (two versus five).

In Table 2 we present our findings relating the characteristics of the SME owner–managers. The management of the firms consisted of a small team, sometimes, just the owner–manager. Only one out of eight firms had a female founder. With regard to the possession of an academic degree, only two owner–managers (cases 2 and 8) had higher education or qualifications.

Data analysis

The empirical work in this paper consists of entrepreneurial personal story explorations. More precisely, this study focuses on descriptive and exploratory approaches to explain the problems faced by the SME. The data were analyzed using content analysis (Weber 1985; Patton 1990). Interviews were transcribed, which was extremely useful during data analysis. It was thus possible to reproduce and re-analyze the collected data. In order to achieve this purpose, we compared the notes systematically to build a database. The interview results were then combined with other documentary evidence cited in “Cases selection and data collecting”, to produce a detailed individual story report.

Variables about difficulties in SME were identified for each firm. These items were then ranked according to the frequency they cited. The development of these techniques allows analysis to focus on specific data, thus overcoming the major problem on qualitative research, i.e. the huge volume of data that is generated. In this study, we selected the failure categories from our literature review, but space was also left for other alternatives that might emerge from the data.

The data interpretation was based on what the respondent stated (first order interpretation) and on a subsequent validation (second order interpretation) to verify the coherence of all the information collected. Finally, a theoretical meaning (third-order interpretation) was applied to the empirical evidence (Newman 1994).

Findings and discussion

Failure factors faced by SME

The objective of this section is to identify the main factors for poor performance and failure faced by Portuguese SME and to determine the real causes and attribution of failure. The list of factors derives from the theoretical framework in “Failure factors in SME”; they were subdivided into external and internal factors. The factors cited by the SME owner–managers are shown in Table 3.

For the economic sector, we found less failure factors cited by optical and electrical engineering firms (cases 1 and 2), whereas the firm dealing with civil engineering faced the broadest range of problems. Interestingly, only the owner–manager of the firm acting within textile equipment manufacturing (case 6) mentioned more internal than external failure factors. Keeping in mind the type of business is important because the factors of failure might be associated with the characteristics of each sector. If there are low entry barriers within a business sector, it demands lower initial capital and less technological knowledge. What also matters, low entry barriers create stronger competition, reducing profit margins and causing difficulties maintaining and developing the businesses.

Likewise, failure factors may be related to the dimensions of the firm. However, considering failure factors from the SME subgroups reveals a heterogenic picture, and in the cases we did not find a specific relationship between firm size and the occurrence of typical external and internal failure factors.

On the whole, from the empirical evidence we can elucidate that more than half of the eight SME studied cited factors for poor performance and failure such as limited access to finance (8), poor market conditions (5), inadequate staff (5), lack of institutional support (5), and lack of co-operation and networking (5). Note that the respondents did not explicitly rank (degree of importance) the factors they mentioned. The low levels of performance mainly originated from or had its root causes in financial and commercial difficulties of the business. Also non-economic criteria were quoted in some cases. However, we emphasize that the key failure factors were found in the growth and development of the firms rather than in their creation.

At a first glance and in a pure quantitative view, external factors were more often cited by the interviewees. Hereby, the problems identified by the majority are hardly new; nevertheless, it is not enough to judge the causes of failure in purely quantitative measures. In fact, in our study we pursue a more qualitative approach in order to gain a richer understanding of the relationship between the failure factors named by the respondents and the ‘real’ causes that we judged as fundamental for stranding. Thus, each factor we identified is going to be completed with content analysis, starting with external factors.

External factors

Within the external factors, all interviewees indicated and described ‘limited access to finance’ to be the main factor that negatively influenced their firms. According to the correspondents, even with considerable planning, the start-up phases of their firms proved to exceed financial estimates. Even if some SME owner–managers received financial support and other types of assistance from local and national government agencies, the chief types of financing to start and develop their firms were personal savings, credit from suppliers and/or clients, and loans from family and friends. This last source was especially used in cases 2 and 5. The owner–manager in case 2 said:

“The very limited use of external financing is due to the fact that supply of funds does not meet the demand… I prefer to maintain control of my business, I do not want to assume disproportionate risks, and lack confidence in the financial institutions.”

The female business-owner in case 1 said that financing agencies demand extensive securities comprising private and business property, which complicates the raising of credit. In sum, we could corroborate the insights from Storey (1994) and Winborg and Landström (2001) that place emphasis on the fact that obtaining equity and debt financing are key difficulties for SME.

Furthermore, ‘poor market conditions’ (cases 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8) as well as ‘strong competitiveness’ (cases 1, 4, 5, and 7) were the determinants mostly cited by the correspondents. Sample quotes follow:

There is a depressed cycle in the market (case 3).

There are extremely strong competitors in the industry (cases 4 and 5).

These quotes illustrate that because of their size and limited resources, the SME studied face severe problems due to the surrounding market conditions. This observation goes along with the insights of Gallup Organization (2007), who found that in comparison with other EU countries especially Portuguese SME complain about high and increasing competition, limited purchasing power of customers, and low turnover growth rates.

Nonetheless, when asked for the reasons of these fierce market conditions, our correspondents’ answers revealed interesting insights. As an example, the owner–managers in cases 3 and 5 mentioned a certain ignorance and non-use of marketing techniques. In general, inadequate product development, lack of market knowledge, as well as problems in product commercialization were frequently cited arguments to justify poor market positioning. The latter are altogether internal factors, which can surely be influenced by the owner–managers themselves and stand for an attributional bias when it comes to judge the causes of poor performance and failure.

Beside the strong competitiveness quoted by most owner–managers, they also mentioned ‘inadequate staff’ (cases 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8) as a difficulty felt by their firms. In concordance with our theoretical considerations (e.g. Bosworth 1989; Gallup Organization 2007), recruiting problems were, in fact, often cited by the interviewees. Due to limited financial resources, engagement of qualified or specialized individuals was described as not easy. Even if they have a university degree, adequate professional experience is often lacking. As a matter of fact, the latter appears to be the key eligibility criterion for human resources. Thus, the female owner–manager in case 1 reported that staff selection is based on experience and not on education. This is the reason why they started to train the staff in-house in a special program in quality and business concepts. The same applies to case 2, whose owner–manager recruits staff from about six other electric companies selecting on the basis of experience rather than education.

The discussions with the owner–managers revealed a remarkable insight. Although most talked about the need for education, the comments from some suggest that they do not necessarily ask for a very high level of education in the small firms. When asked what is the ideal qualification for his firm some respondents suggested basic literacy. Also, the hiring practice of many, which favors the experienced over the educated somewhat, confirms this. Most employers appear to prefer lower educated staff that they could extensively train and indoctrinate into loyalty and long service. Indeed, this theory has support from some educational studies from Portugal (Sousa 1991). Thus, the SME studied are quite conscious about the importance of in-house education and training programs for their employees.

The factor ‘lack of institutional support’ (cases 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7) was also a difficulty frequently cited. Interestingly, all interviewees are aware of the importance and advantages of physical, organizational, and cultural support institutions. In some cases, mainly in cases 2 and 6, when institutional support was used to create and to develop the business, respondents refer that this support is very important: without that incentive, they would probably not have started the venture. However, in the majority of cases studied this institutional support does not exist, which is particularly true for financial assistance. The correspondents also complained about disequilibrium between the offers made by support institutions and the real demand on the part of the SME. The type of support most needed was financing to acquire equipment and to hire employees. In some cases (case 2), training and help on the bureaucratic processes was solicited.

In the sample, some owner–managers did not even have knowledge about the existence of institutional support or they did not trust the system. For example, in case 5 the respondent mentioned that he still has not decided yet whether to attend the supporting institution to further develop his business. Scepticism against outside help, as noted by Ghobadian and Galler (1996), can be found also among our correspondents. However, problems with institutional assistance, also in terms of pecuniary support, were mostly assigned to the local authorities. That is, many of the difficulties before mentioned were judged, from the business-owners perspective, as a consequence of a lack of support from public authorities.

Internal factors

Concerned with internal factors, we found that five firms mentioned ‘lack of co-operation and networking’ (cases 1, 3, 5, 5, and 7). The main reasons were that the co-operation and information sharing created some friction and conflicts among partners. The interviewee in case 8 confirmed that he already collaborates with some subcontractors. He also indicated that the relationships are not always without friction. The main problems arise from ‘stealing’ employees from other companies, which again was attributed to outside reasons. Overall, our observations confirm that, generally speaking, inadequate social capital and therewith lack of co-operation and networking impose severe problems for the development of the SME studied. Nevertheless, we also observed that the SME owner–managers were not really concerned about the importance of co-operation and networking, which literature identifies as crucial for the firm’s success (e.g. Brüderl and Preisendörfer 1998; Franco 2003; Teng 2007).

‘Obsolete technology and lack of innovation’ (cases 4, 5, 6, and 7) was another problem faced by some cases studied. The firm of case 7 produces complex products (plastics manufacture). However, the company does not have a complex system of producing, packaging, and delivering directly to the warehouse. The company also does not renovate its product development by investing in the development of products for specific customers. Similarly, other companies (cases 4, 5, and 6) are not seeking for innovations and improvements. High technology and research is not common in these firms as observations and discussions revealed. This is in line with Gallup Organization (2007), who found that one third of all Portuguese SME seem to have difficulties in implementing new technologies. This failure factor also relates to the low-level of education, and the personalized managerial style of running the business, as follows.

Four interviewees mentioned ‘lack of entrepreneurial qualification’ (cases 2, 3, 4, and 8) as a difficulty in starting and managing their firms. Table 3 reveals that only two out of eight owner–managers (case 2 and 8) have university-level degrees, whereas most of our interviewees (five cases) possess education at the secondary level. There appears to be a trend that years of schooling and higher education level are positively associated with a firm’s performance, as already shown by Bates (2005).

With regard to prior experience in running a business, positively related with a firm’s success (Gimeno et al. 1997; Madsen et al. 2003; Bosma et al. 2004), in Table 3 we see that the majority of firms studied (cases 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) had no practice or experience in running a business before. Even if our sample is very limited in quantitative terms, we strongly believe that, despite the problems of hiring qualified staff, the real concern for the low education and experience seems to originate from the owner–managers themselves. Lacking higher education levels and entrepreneurial experience are main difficulties for the SME in our sample. Nonetheless, these constraints were not thematized in the discussions we had with the interviewees.

Strongly linked to the factors discussed before, is ‘poor management strategy and vision’ as another important determinant of poor performance and failure. Due to their size and limited human resources, SME typically lack the middle managers or functional specialists who in large firms play a major role in developing and implementing organizational strategies. As a consequence, SME owner–managers carry out a multiplicity of roles (Jennings and Beaver 1997), which makes strategic management complex and owner-focused. We found sensitivity for the importance of planning skills and management vision in the medium-sized enterprise with organizational complexity (case 7). Those few who complained about this weakness were the owners of the small businesses (cases 3, 6, and 8). The following quote of case 8 is illustrative:

“The major difficulty in my firm is probably the lack of planning and strategy and its inability to recognize the marketplace and strong competition.”

Nevertheless, we detected only little efforts to overcome these deficiencies. Again, the micro-sized businesses (cases 1, 2, 4, and 5) showed the lowest preoccupation in this field. Not surprisingly then, lack of management strategy and vision which was one of the most frequent failure factors we found through our explorations, and an evident attributional error seems to go along with this factor.

In sum, the analysis indicates some interesting findings. In general, we found support for the assumption of an attributional bias among SME owner–managers when it comes to identify the causes of poor performance and failure. That is to say because poor performance and failure were attributed mainly to the external factors such as limited access to finance, poor market conditions, inadequate staff availability, and lack of institutional support. However, through our exploration the real causes appear rather to be related to a lacking strategy and vision, low educational levels, and an inadequate social capital. The awareness regarding internal weaknesses were found to be limited, and if internal factors were cited they were sometimes assigned to external influences, as it is the case of co-operation and networking.

Conclusions, implications, and limitations

SME play a predominant role in fostering income stability, growth, and employment. As they have specific strengths such as flexibility and adaptability, they also face a series of difficulties and disadvantages with respect to larger companies. These weaknesses require special policy responses. In order to formulate adequate SME support, it is not sufficient to merely analyze the factors for poor performance and failure, it is rather imperative to explore if SME owner–managers are really aware of the actual causes. In fact, if SME owner–managers attribute their problems to external factors independently from the real origins, they admit that they cannot control the success or failure of their firms (Zacharakis et al. 1999). Consequently, if SME owner–managers call for specific assistance and programs, those measures might end up to be designed far from the real constraints they face. Attributing poor performance and failure to the true causes is, thus, an important step towards the development of appropriate SME policies.

Nevertheless, our qualitative research performed within the Portuguese context reveals that the SME owner–managers attribute poor performance of their firms mainly to causes that differ from reality. External factors were more often cited, but qualitative analysis shows that internal failure factors are imminent and not satisfactorily recognized. When considered along with attribution theory (Heider 1958; Kelley 1967 and Weiner 1979, 1985), this insight is not amazing; as from an attributional perspective individuals are likely to ascribe their failures to external causes (Miller and Ross 1975; Zuckerman 1979; Bettman and Weitz 1983; Davis and Gardner 2004) and to situational factors (Fiske and Taylor 1991), rather than blaming themselves. For the SME owner–managers in our study, we can confirm a strong attributional bias in form of an attribution error, apparently a key determinant in their firms’ failure.

These insights lead us to some recommendations for policy-makers, small business owners, consultants, and researchers. Specific legislative and administrative provisions for SME must take into account that SME owner–managers might sometimes not be aware of their real constraints. Educators and practitioners in small business management are suggested to consider cognitive biases and attributional errors. Overcoming deficiencies in management skills, strategy and vision, as wells as co-operation and networking is the main task when designing SME support. Eventually, SME owner–managers should be more sensitized for the numerous programs including financing, training, further education, and information services provided by public or private institutions.

For future research lines, based on our findings from face-to-face interviews, observations, and other evidence, we conclude that the unsuccessful SME could be best explained by qualitative explorations. Thus, we advocate that researchers should redirect some efforts from the vast number of cases to study the particular failure factors faced by selected firms. In addition, as our study focuses on Portuguese SME, a comparison within different economic and cultural settings could be helpful to obtain more general conclusions.

Finally, it should be noted that our study has a number of limitations. First, the applied methodology might have potential pitfalls. The explicit subjectivity of entrepreneurial personal story explorations, which concentrates on the individuals’ narrative, neglects other social actors’ interpretations and objective validations. General policy conclusions should, therefore, be drawn cautiously (Perren and Ram 2004). Second, besides secondary data sources, our findings are mainly based on interviews with the owner–managers as well as on our personal observations and impressions when visiting the firms, which may result in self-report and auto-evaluation bias. Third, readers are asked to keep the focused number of cases in mind. Fourth, our findings are taken from the Portuguese context, with an idiosyncratic economic structure and climate. Nonetheless, we hope that this exploratory study sparks further research interest to explore the issue of failure factors in SME and their attributional errors.

References

Agarwal, R., & Gort, M. (1996). The evolution of markets and entry, exit and survival of firms. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 489–498. doi:10.2307/2109796.

Aldrich, H. E., Rosen, B., & Woodward, W. (1987). The impact of social networks on business foundings and profit: a longitudinal study. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 154–168.

Almus, M., & Nerlinger, E. A. (1999). Growth of new technology-based firms: which factors matter? Small Business Economics, 13, 141–154. doi:10.1023/A:1008138709724.

Audretsch, D. (1991). New-firm survival and the technological regime. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 73, 441–450. doi:10.2307/2109568.

Audretsch, D. (1995). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 441–457. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(95)00499-8.

Audretsch, D., & Mahmood, T. (1995). New firm survival: new results using a hazard function. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 77, 97–103. doi:10.2307/2109995.

Barber, J., Metcalfe, J., & Porteous, M. (1989). Barriers to growth: the ACARD study. In J. Barber, J. Metcalfe & M. Porteous (Eds.), Barriers to growth in small firms. London: Routledge.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108.

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 551–559. doi:10.2307/2109594.

Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 343–358. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.003.

Bettman, J., & Weitz, B. (1983). Attributions in the boardroom: causal reasoning in corporate annual reports. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 165–183. doi:10.2307/2392616.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 107–117. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(85)90010-2.

Bosma, N., Van Praag, M., Thurik, R., & de Wit, G. (2004). The value of human and social capital investments for the business performance of startups. Small Business Economics, 23, 227–236. doi:10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000032032.21192.72.

Bosworth, D. (1989). Barriers to growth: the labour market. In J. Barber, J. S. Metcalfe & M. Porteous (Eds.), Barriers to growth in small firms. London: Routledge.

Brown, J. D., Earle, J. S., & Lup, D. (2005). What makes small firms grow? finance, human capital, technical assistance, and the business environment in Romania. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54, 33–70. doi:10.1086/431264.

Brüderl, J., & Preisendörfer, P. (1998). Network support and success of newly founded businesses. Small Business Economics, 10, 213–225. doi:10.1023/A:1007997102930.

Brüderl, J., & Preisendörfer, P. (2000). Fast growing businesses: empirical evidence from a German study. International Journal of Sociology, 30, 45–70.

Brüderl, J., Preisendörfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological Review, 57, 227–242. doi:10.2307/2096207.

Brüderl, J., Preisendörfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1996). Der Erfolg neugegründeter Unternehmen—Eine empirische Studie zu den Chancen und Risiken von Unternehmensgründungen. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot.

Bruno, A. V., Leidecker, J. K., & Harder, J. W. (1986). Patterns of failure among Silicon Valley High Technology Firms. In J. Hornaday, F. Tarpley, J. Timmons & K. Vesper (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurial research (pp. 677–694). Wellesley: Babson Center for Entrepreneurial Research.

Centro de Inovação Empresarial da Beira Interior—CIEBI. (2005). Estudo da sustentabilidade das Empresas Recém Criadas. Covilhã, Portugal.

Chetty, S. K. (1996). The case study method for research in small and medium sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 15, 73–85. doi:10.1177/0266242696151005.

Cope, J., & Watts, G. (2000). Learning by doing: an exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 6, 104–124. doi:10.1108/13552550010346208.

Davis, W. D., & Gardner, W. L. (2004). Perceptions of politics and organizational cynicism: an attributional and leader-member exchange perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 439–465. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.05.002.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (1994). Handbook of qualitative methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dollinger, M. J. (1999). Entrepreneurship: strategies and resources. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Dowling, M. (2003). Erfolgs- und Risikofaktoren bei Neugründungen. In M. Dowling & H. J. Drumm (eds.). Gründungsmanagement. Vom erfolgreichen Unternehmensstart zu dauerhaftem Wachstum (2nd ed., pp. 19–31), Berlin et al.: Springer.

European Network for SME Research—ENSR. (2003). Observatory of European SMEs 2003, No 7: SMEs in Europe 2003. In European Commission (Ed.), Brussels: European Commission.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Forbes, D. P. (2005). Are some entrepreneurs more overconfident than others? Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 623–640. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.05.001.

Franco, M. J. (2003). Collaboration among SMEs as a mechanism for innovation: an empirical study. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 6, 23–32.

Gallup Organization. (2007). Observatory of European SMEs, No 196. In European Commission (Ed.), Brussels: European Commission.

García-Muiña, F. E., & Navas-López, J. E. (2007). Explaining and measuring success in new business: the effect of technological capabilities on firm results. Technovation, 27, 30–46. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2006.04.004.

Gatewood, E. J., Shave, K. G., & Gartner, W. B. (1995). A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing start-up behaviours and success at venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 371–391. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(95)00035-7.

Ghobadian, A., & Galler, D. N. (1996). Total quality management in SMEs. International Journal of Management Science, 16, 83–106.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., & Woo, C. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783. doi:10.2307/2393656.

Grant, P., & Perren, L. J. (2002). Small business and entrepreneurial research: metatheories, paradigms and prejudices. International Small Business Journal, 20(2), 185–211. doi:10.1177/0266242602202004.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1989). Organizational ecology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Hemer, J., Berteit, H., Walter, G., & Göthner, M. (2006). Erfolgsfaktoren für Unternehmensausgründungen aus der Wissenschaft. In Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Ed.), Studien zum deutschen Innovationssystem Nr. 05–2006, Berlin.

IAPMEI. (2004). Estrutura empresarial em Portugal, Edição do Instituto de Apoio às Pequenas e Médias Empresas e ao Investimento, Portugal.

Jennings, P., & Beaver, G. (1997). The performance and competitive advantage of small firms: a management perspective. International Small Business Journal, 15, 63–75. doi:10.1177/0266242697152004.

Kakati, M. (2003). Success criteria in high-tech new ventures. Technovation, 23, 447–457. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00014-7.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), The Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 192–238). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kent, R. L., & Martinko, M. J. (1995). The measurement of attributions in organizational research. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Attribution theory: An organizational perspective. Delray Beach: St. Lucie.

Lechner, C., & Dowling, M. (2003). Firm networks: external relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 15, 1–26. doi:10.1080/08985620210159220.

Lin, C. Y. (1998). Success factors of small-and medium sized enterprises in Taiwan: an analysis of cases. Journal of Small Business Management, 36, 43–56.

Madsen, H., Neergaard, H., & Ulhøi, J. P. (2003). Knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship and human capital. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 10, 426–434. doi:10.1108/14626000310504738.

Martinko, M. (1995). The nature and function of attribution theory within the organizational sciences. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Attribution theory: An organizational perspective. Delray Beach: St. Lucie.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (1994). Life duration of new firms. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 42, 227–245. doi:10.2307/2950567.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2002). The survival of new domestic and foreign-owned firms. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 323–343. doi:10.1002/smj.217.

McAuley, E., Duncan, T. E., & Russell, D. W. (1992). Measuring causal attributions: the revised causal dimension scale (CDII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 566–573. doi:10.1177/0146167292185006.

Miller, D. T., & Ross, M. (1975). Self-serving biases in attribution of causality: fact or fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 82, 213–225. doi:10.1037/h0076486.

Newman, W. L. (1994). Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative methods, qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon Cop.

Paffenholz, G. (1998). Krisenhafte Entwicklungen in mittelständischen Unternehmen. Ursachenanalyse und Implikationen für die Beratung. IfM-Materialien Nr. 130. Bonn.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. California: Sage.

Pennings, L., Lee, K., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (1998). Human capital, social capital, and firm dissolution. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 425–440. doi:10.2307/257082.

Perren, L., & Ram, M. (2004). Case-study method in small business and entrepreneurial research—mapping boundaries and perspectives. International Small Business Journal, 22, 83–101. doi:10.1177/0266242604039482.

Porter, M. (1990). The comparative advantage of nations. London: Macmillan.

Sousa, E. (1991). Família e trabalho: um quadro de estabilidade. Organizações e Trabalho, No. 5/6, 63–74.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. Routledge: London.

Tang, J., Tang, Z., & Lohrke, F. T. (2008). Developing an entrepreneurial typology: the roles of entrepreneurial alertness and attributional style. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4, 273–294. doi:10.1007/s11365-007-0041-4.

Teece, D. (1998). Capturing value from knowledge assets: the new economy, markets for know-how and intangible assets. California Management Review, 40, 55–79.

Teng, B. S. (2007). Corporate entrepreneurship activities through strategic alliances: a resource-based approach toward competitive advantage. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 119–142. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00645.x.

Timmons, J. A. (1994). New venture creation: entrepreneurship for the 21st century. Homewood: Irwin.

Van Praag, C. M. (2003). Business survival and success of young small business owners: an empirical analysis. Small Business Economics, 21, 1–17. doi:10.1023/A:1024453200297.

Van Praag, C. M., & Cramer, J. S. (2001). The roots of entrepreneurship and labor demand: individual ability and low risk aversion. Economica, 68, 45–62. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.00232.

Wagner, J. (1994). The post-entry performance of new small firms in german manufacturing industries. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 42, 141–154. doi:10.2307/2950486.

Weber, R. (1985). Basic content analysis. California: Sage.

Weiner, B. (1979). A theory of motivation for some classroom experience. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 3–25. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.3.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attribution theory of achievement motivation and innovation. Psychological Review, 92, 548–573. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548.

Weiner, B. (1995). Attribution theory in organizational behavior: a relationship of mutual benefit. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Attribution theory: an organizational perspective (pp. 3–6). Delray Beach: St. Lude.

Westhead, P., & Cowling, M. (1995). Employment change in independent owner-managed high-technology firms in Great Britain. Small Business Economics, 7, 111–140. doi:10.1007/BF01108686.

Winborg, J., & Landström, H. (2001). Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: examining small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 235–254. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00055-5.

Woywode, M. (1998). Determinanten der Überlebenswahrscheinlichkeit von Unternehmen, ZEW Wirtschaftsanalysen, Bd. 25, Baden-Baden.

Yin, R. (1989). Case study research. Newbury Park: Sage.

Zacharakis, A., Meyer, G. D., & DeCastro, J. (1999). Differencing perceptions of new venture failure: a matched exploratory study of venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 37, 1–14.

Zuckerman, M. (1979). Attribution of success and failure revisited, or the motivational bias is alive and well in attribution theory. Journal of Personality, 47, 245–287. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1979.tb00202.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, M., Haase, H. Failure factors in small and medium-sized enterprises: qualitative study from an attributional perspective. Int Entrep Manag J 6, 503–521 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0124-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0124-5