Abstract

A well-preserved oral function is key to accomplishing essential daily tasks. However, in geriatric medicine and gerodontology, as age-related physiological decline disrupts several biological systems pathways, achieving this objective may pose a challenge. We aimed to make a systematic review of the existing literature on the relationships between poor oral health indicators contributing to the oral frailty phenotype, defined as an age-related gradual loss of oral function together with a decline in cognitive and physical functions, and a cluster of major adverse health-related outcomes in older age, including mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls. Six different electronic databases were consulted by two independent researchers, who found 68 eligible studies published from database inception to September 10, 2022. The risk of bias was evaluated using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Toolkits for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. The study is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021241075). Eleven different indicators of oral health were found to be related to adverse outcomes, which we grouped into four different categories: oral health status deterioration; decline in oral motor skills; chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders; and oral pain. Oral health status deterioration, mostly number of teeth, was most frequently associated with all six adverse health-related outcomes, followed by chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders associated with mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, hospitalization, and falls, then decline in oral motor skills associated with mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, hospitalization, and quality of life, and finally oral pain was associated only with physical frailty. The present findings could help to assess the contribution of each oral health indicator to the development of major adverse health-related outcomes in older age. These have important implications for prevention, given the potential reversibility of all these factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The last few decades have recorded a number of welcome changes in the global population. Demographic growth and life expectancy are impressive, but population aging is becoming a pressing concern, especially in upper-middle-income countries with a lifespan exceeding 80 years. The main concerns revolve around the quality of the additional years to be lived compared to previous generations; this issue is currently very sensitive [1]. One priority is to better address care challenges posed by older adults while reducing the burden of healthcare resulting from the aging population. As well as improving the overall quality of health in older age, this aim is driving the scientific community to make considerable efforts to develop strategies for the early detection of unhealthy aging phenotypes.

In this respect, deteriorating physical and behavioral functioning is emerging as an increasing burden in long-term healthcare for the aging population. Of greatest concern is the vulnerable subset comprising older adults with multimorbidity, dementia, frailty, and other major adverse health-related outcomes requiring increased care and inducing greater dependency, including hospitalization. Epidemiological evidence suggests that most of these are overlapping, although clinically separate, entities [2]. Indeed, multimorbidity contributes to frailty, functional disability, and increased healthcare costs and also increases the potential for substandard care, given the peculiar treatment setting in clinical practice. Besides, frailty and functional disability accelerate the hazard risk trajectories of adverse health-related outcomes, including mortality.

Oral health is critical to preserving good general health [3]. Geriatric medicine is demonstrating that poor oral health is associated with age-associated physiological burdens, physical frailty [4], sarcopenia [5], cognitive impairment [6], and accumulating multimorbidity [7]. Some biological explanations have been advanced to explain the causal association between poor oral health and age-related physical frailty. The hypothesis of a biological common line between oral health and the different domains of the physical frailty phenotype has been raised. These domains include the functional sphere, through chronic inflammation; the psychosocial aspects, impacting self-esteem and inducing late-life depression (LLD); and the therapeutic approach, involving prevention and damage control [8].

On the basis of these strict links between frailty and oral health indicators, the oral frailty phenotype has been proposed as a conceptualization of age-related gradual loss of oral function, driven by a set of impairments (i.e., loss of teeth, poor oral hygiene, inadequate dental prostheses, difficulty in chewing associated with age-related changes in swallowing) that worsen oral daily practice functions [9, 10]. This novel construct has been defined as a decrease in oral function together with a decline in cognitive and physical functions, as well as possible relationships among oral frailty, oral microbiota, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and neurodegeneration [11].

Over and above all, poor oral health has a role in driving the risk of hospitalization due to infectious and non-infectious diseases. In this context, the awareness of the risk of developing periodontal disease among individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus [12], coronary heart disease [13], respiratory disease [14], and osteoporosis [15] is a recently acquired concept. Indeed, oral infections may be a significant risk factor for systemic diseases, and therefore timely oral health management is critical also to manage non-communicable chronic diseases [16].

All these assumptions, along with the insidious association with survival rates [17], make oral wellbeing a key concept to be preserved, from the preventive and treatment perspective. A large community-based cohort study over a 44-year follow-up demonstrated that number of teeth, marginal bone, and dental plaque were associated with all-cause mortality [18]. Indeed, improving oral health may work well in influencing survival trajectories. Polzer and colleagues demonstrated that treatment of tooth loss protected against mortality [19]. A similar systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that oral care intervention during hospitalization could lead to more favorable mortality-related outcomes [20]. The complex and multidimensional nature of the oral function makes it difficult to clarify its role in affecting adverse health-related outcome trajectories in older age. Therefore, we set up the present systematic review with the aim of summarizing existing evidence about oral health indicators that may be significantly involved in determining a cluster of major adverse health-related outcomes in older age, including mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls.

Methods

Search strategy and data extraction

The present systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines, adhering to the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist [21]. We performed separate searches in the US National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), EMBASE, Scopus, Ovid, and Google Scholar databases to find original articles probing any association between exposure to poor oral health indicator(s) and adverse health-related outcomes in older age. The exposure factors were selected to include any indicator(s) of poor oral health, regardless of the measurement method (clinical examination or self‐reported), and the outcome(s) included major adverse health-related outcomes of aging, i.e., mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls. The search strategy used in PubMed and MEDLINE and adapted to the other four electronic sources is shown in Supplementary Table S1. The literature search covers the timeframe from the database inception to September 10, 2022. No language limitation was introduced. Two investigators (VD, ML) searched for papers, screened titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles separately and in duplicate, checked the complete texts, and selected records for inclusion.

Protocol and registration

An a priori protocol was established and registered, without particular amendments to the information provided at registration, on PROSPERO, a prospective international register of systematic reviews (CRD42021241075). Age over 60 years was an inclusion criterion applied when skimming for original papers correlating item(s) referred to poor oral health status and major adverse health-related outcomes linked to the aging process. No skimming was applied to the recruitment settings (home care, hospital, community) or general health status. Technical reports, letters to the editor, and systematic and narrative review articles were excluded.

The following information was extracted by the two investigators (VD, ML) separately and in duplicate in a piloted form: (1) general information about single studies (author, year of publication, country, settings, design, sample size, age); (2) item(s) referred to poor oral health; (3) arbitrarily selected major adverse health-related outcomes in older age (mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls). No skimming was applied to assessment methods used to evaluate functional disability and quality of life, while frailty was identified only with the physical frailty phenotype according to the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) criteria proposed in 2001 [22] or similar tools or criteria. This choice was driven by a previous systematic review that found 39 articles, when not restricting the search to the most widely used frailty model [8]. The exposure included every oral health indicator measured at least once in the study, regardless of the form of measurement (clinical exam, self-reported). All references selected for retrieval from the databases were managed with the commonly used MS Excel software platform for data collection. Then, all duplicated records were excluded. Potentially eligible articles were identified by reading the abstract and, if warranted, then reading the full-text version of the articles. Data were cross-checked, any discrepancies were discussed, and disagreements were resolved by a third investigator (FP). Lastly, data extracted from selected studies were structured in tables of evidence.

Quality assessment within and across studies and overall quality assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was independently appraised by paired investigators (VD and ML or FP), using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Toolkits for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [23] (National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2018). The ratings high (good), moderate (fair), or poor were assigned to studies according to the criteria stated in the toolkit. This tool contains 14 questions that assess several aspects associated with the risk of bias, type I and type II errors, transparency, and confounding factors, i.e., study question, population, participation rate, inclusion criteria, sample size justification, time of measurement of exposure/outcomes, time frame, levels of the exposure, defined exposure, blinded assessors, repeated exposure, defined outcomes, loss to follow-up, and confounding factors. Items 6, 7, and 13 do not refer to cross-sectional studies and the maximum possible scores for cross-sectional and prospective studies were 8 and 14, respectively. Disagreements regarding the methodological quality of the included studies were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached, or resolved by a fourth investigator (FL). A modified version of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating system was used to assess the overall quality of evidence of the studies included in the present systematic review [24]. The following factors were considered: the strength of association for poor oral health indicator(s) and adverse health-related outcomes, methodological quality/design of the studies, consistency, directedness, precision, size, and (where possible) dose–response gradient of the estimates of effects across the evidence base. Evidence was graded as very low, low, moderate, and high, similar to a GRADE rating system.

Results

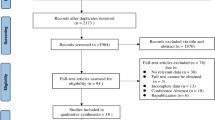

The preliminary systematic search of the literature yielded 30,804 records. After excluding duplicates and records removed for other reasons, 2224 were considered potentially relevant and retained for the analysis of titles and abstracts. Then, 1399 articles were excluded for failing to meet the characteristics of the approach or the review goal. After reviewing the full text of the remaining 825 articles, only 68 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final qualitative analysis (Table 1) [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. The PRISMA 2020 flow chart illustrating the number of studies at each stage of the review is shown in Fig. 1. The endpoints of the literary skimming process resulting in 68 eligible articles evaluating eleven different oral health indicators are listed as follows: masticatory function, tongue pressure, occlusal force, oral diadochokinesis, dry mouth, oral health, periodontal disease, number of teeth, difficulties in chewing, difficulties in swallowing, and tooth or mouth pain (Fig. 2). Given the original heterogeneous labeling, which prevented a rapid conceptual interpretation, we grouped oral health factors into four separate categories: oral health status deterioration (number of teeth, oral health, and periodontal disease); decline in oral motor skills (masticatory function, oral diadochokinesis, occlusal force, and tongue pressure); chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders (dry mouth, difficulties in swallowing, and difficulties in chewing); and oral pain (tooth or mouth pain).

Eleven oral health items associated to the identified four categories (oral health status deterioration; decline in oral motor skills; chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders; oral pain), related to six adverse health-related outcomes (mortality, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls)

Details of the design (cohort or cross-sectional), sample size (N) and gender ratio (%), minimum age and mean (SD), setting (community, hospital, home care), and country of included studies are shown in Table 1. Given the mixed shape of the recruitment settings for a small percentage of selected studies (2 of the 68), the distribution resulted as follows: 80% (N = 56) community, 17.15% (N = 12) hospital, and 2.85% (N = 2) nursing homes. The Asian continent led the geographical distribution of selected studies (57.14%, N = 40), followed by Europe (28.60%, N = 20, of these 2 studies were from Europe (UK)/North America (USA)), South America (5.70%, N = 4), North America (7.14%, N = 5), and Oceania (1.42%, N = 1) (Figure S1). This latter perspective pointed to both the lack of homogeneity in geographical distribution and the inadequate representativeness of all continents. Mean (SD) age and gender ratio of study participants were recorded if applicable. Across a total of 426,538 subjects, the gender distribution was balanced (48% males versus 52% females). A longitudinal cohort design was more common than cross-sectional (73.5%, N = 50 versus 25%, N = 17); there was only one retrospective study (1.5% N = 1).

Adverse health-related outcomes assessment tools and their distribution across studies

The percentage distribution of the different adverse health-related outcomes investigated in selected studies is shown in Fig. 3. Given the multiplicity of adverse health-related outcomes observed in 5 of the 68 selected studies, in total, 75 outcomes were recorded as the denominator when calculating the representativeness of each adverse health-related outcome. More specifically, three studies were found to simultaneously evaluate two different outcomes each (two of them investigating mortality and functional disability [48, 49], and one investigating hospitalization and mortality [75]), while two studies evaluated three different outcomes, i.e., functional disability, hospitalization, and mortality [65, 66]. Overall, mortality was found to be the most common (38.67%, N = 29 out of 75), followed by physical frailty (29.34%, N = 22 of 65), functional disability (16%, N = 12 of 75), quality of life (8%, N = 6 of 75), hospitalization (5.33%, N = 4 of 75), and falls (2.66%, N = 2 of 75).

As regards the different types of quality of life assessment tools, both the Brazilian validated version of WHOQOL-BREF (25%, N = 2) and the EUROQOL 5D (EQ-5D) (25%, N = 2) were the most frequently adopted, followed by the Short Form 36-Items Health Survey (12.5%, N = 1), the German version of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (PGCMS) (12.5%, N = 1), the General Life Satisfaction (GLS) (12.5%, N = 1), and the Satisfaction With individual Health status (SWH) (12.5%, N = 1). Of the 6 studies focused on quality of life, one used three different assessment tools [64], while the remaining five each used only one tool [38, 45, 51, 67, 77].

There were 11 studies focused on the functional disability outcome; among them, the most common tool adopted was the certification for Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) (50%, N = 6), followed by the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (16.8%, N = 2), the Functional Independence Measure motor score (FIM) (8.3%, N = 1), the 12-items of behavioral status (8.3%, N = 1), a clinical assessment to evaluate mobility limitations, ADL, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (8.3%, N = 1), and a single-item questionnaire (8.3%, N = 1), each of which was used only once.

Association among oral health indicators and different adverse health-related outcomes

Mortality was found to be the most studied outcome. We recorded prevailing markers of oral health status deterioration (62.18%), driven by the number of teeth (32.44%, N = 12), followed by the items oral health (16.22%, N = 6) and periodontal disease (13.52%, N = 5) (Fig. 4, panel A). The burden of items belonging to the categories chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders and decline in oral motor skills was similar (24.32% and 13.5%, respectively). For the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category, the item difficulties in chewing was most frequently associated with mortality (16.22%, N = 6), followed by dry mouth (8.1%, N = 3). For the decline in oral motor skills category, the item occlusal force was most frequently associated with mortality (8.1%, N = 3), followed by masticatory function (5.4%, N = 2) (Fig. 4, panel A).

Doughnut chart for the four categories of oral health items (oral health status deterioration; decline in oral motor skills; chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders; oral pain), and combined with the corresponding eleven indicators of oral health and relative metrics for each of the heath-related adverse outcomes: mortality (a), physical frailty (b), functional disability (c); quality of life (d), hospitalization (e), and falls (f)

For physical frailty, we recorded prevailing markers of oral health status deterioration (51.04%), driven by the number of teeth (30.62%, N = 15), followed by the items oral health (11.36%, N = 5) and periodontal disease (12.26%, N = 6) (Fig. 4, panel A). For the decline in oral motor skills category, the items masticatory function (8.16%, N = 4) and oral diadochokinesis (8.16%, N = 4) were most frequently associated with physical frailty, while the items tongue pressure (6.12%, N = 3) and occlusal force (6.12%, N = 3) were less common (Fig. 4, panel A). For the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category, the item difficulties in chewing was most frequently associated with physical frailty (8.16%, N = 4) compared to the items dry mouth (6.12%, N = 3) and difficulties in swallowing (4.08%, N = 2). Finally, we found oral pain to be the category least investigated, including only 2.04% (N = 1) of the oral items linked to physical frailty (Fig. 4, panel A).

For functional disability, we found higher representativeness of items of the oral health status deterioration category (66.68%), driven by the number of teeth (46.68%, N = 7), followed by the item oral health (13.34%, N = 2) and periodontal disease (6.66%, N = 1) (Fig. 4, panel A). For the decline in oral motor skills category, the association of the items masticatory function and occlusal force with functional disability was the same (6.66%, N = 1). Finally, for the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category, we found that only the items difficulties in swallowing (13.34%, N = 2) and dry mouth (6.66%, N = 1) were related to functional disability (Fig. 4, panel A).

For quality of life, we identified an overwhelming prevalence of the oral health status deterioration (85.71%) category, driven by oral health (42.86%, N = 2), followed by number of teeth (28.57%, N = 2), and periodontal disease (14.29%, N = 1) (Fig. 4, panel B). The only other category investigated was a decline in oral motor skills (14.29%) covered by the item masticatory function (14.29%, N = 1) (Fig. 4, panel B).

For the hospitalization outcome, each of the categories was represented by a single item, namely oral health (25%, N = 1) for the oral health status deterioration category (25%), masticatory function (25%, N = 1) for the decline in oral motor skills category (25%), and difficulties in swallowing (50%, N = 2) for the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category (50%) (Fig. 4, panel B).

Finally, only two items were found to be associated with falls, the item number of teeth (66.66%, N = 2), representing the oral health status deterioration category (66.66%), and the item dry mouth (33.34%, N = 1), representing the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category (33.34%) (Fig. 4, panel B).

Risk of bias across studies and overall quality of evidence for oral health items associated with adverse age-related outcomes

Examining all 68 included studies, we found a moderate (n=14) to high (n=54) methodological quality (Table 1). An overview of quality ratings within (panel A) and across studies (panel B) is shown in Fig. 5, highlighting areas with higher or lower risk ratings. Bias was detected predominantly in the domains of blinded assessors (detection bias) (68/68 studies, 100% of studies with a higher risk of bias) and sample size justification (selection bias) (66/68 studies, 97% of studies with a higher risk of bias) and, to a lower extent, in the domains of multiple exposure (40/51 prospective/retrospective studies, 78% of studies with a higher risk of bias), participation rate (17/68 studies, 25% of studies with a higher risk of bias), and different levels of exposure (16/68 studies, 23% of studies with a higher risk of bias) (Fig. 5, panel B). Using the GRADE approach, the overall quality of evidence of our four categories was judged moderate for oral health status deterioration; low to moderate for decline in oral motor skills; low for chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders; and very low for oral pain (Table 2).

Discussion

The present systematic review explored the relationship between several oral health indicators and their role in determining adverse health-related outcomes including death, physical frailty, functional disability, quality of life, hospitalization, and falls in older age. For the outcome mortality, we recorded prevailing markers of the categories oral health status deterioration; chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders; and decline in oral motor skills, driven by the items: number of teeth, difficulties in chewing, and occlusal force. For physical frailty, we found associations with indicators of oral health status deterioration (number of teeth), decline in oral motor skills (masticatory function), and chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders (difficulties in chewing). For functional disability, we found higher representativeness of the oral items number of teeth (oral health status deterioration category), masticatory function/occlusal force (decline in oral motor skills category), and dry mouth (chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders). For quality of life, we identified an overwhelming prevalence of the oral health status deterioration category driven by the item oral health. The oral item most frequently associated with the hospitalization outcome was difficulties in swallowing for the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category, while only two oral health items were found to be associated with falls, namely number of teeth for the oral health status deterioration category and dry mouth for the chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category.

The present findings suggest that the oral health indicator most frequently associated with mortality was the number of teeth. Edentulism is an important oral health indicator in older age [93], capturing cumulative effects of oral diseases over the life course [94]. Worldwide, approximately 30% of adults aged 65–74 years are edentulous, periodontal disease being the primary cause [95]. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported reduced survival rates among older edentulous individuals [19, 96, 97]. In particular, in a linear dose–response analysis, Peng and colleagues found 15%, 33%, and 57% increments in the relative risks of all-cause mortality per 10-, 20-, and 32-tooth loss [97]. The present findings also suggest relationships between a reduced occlusal force and higher mortality and between difficulties in chewing and increased survival in older age; these lack previous systematic review/meta-analytical evidence.

Limiting our search to physical frailty, we found an association with indicators of oral health status deterioration, decline in oral motor skills, and chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders, driven by the items number of teeth, masticatory function, and difficulties in chewing, respectively. In a previous systematic review of all frailty models, we found 12 oral health indicators linked to frailty [8], while another very recent systematic review found 7 oral health characteristics linked to frailty status [4]. Of these oral factors, only three were present in both systematic reviews: number of teeth, difficulties in chewing, and periodontal disease [4, 8]. Two of these three oral items were confirmed in this systematic review focused only on physical frailty, i.e., number of teeth and difficulties in chewing.

For functional disability, we found higher representativeness of the oral items number of teeth for the oral health status deterioration category and masticatory function/occlusal force for the decline in oral motor skills category. For these items, there were no previous systematic reviews/meta-analyses that investigated the relationship with functional disability. We also identified an overwhelming prevalence of the oral health status deterioration category (item oral health) associated with quality of life in older age. In this context, oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is a distinct aspect of health-related quality of life [98]. Together with orofacial pain, orofacial appearance, and psychosocial impact, oral function is one of the four dimensions of the OHRQoL [99]. These four suggested dimensions have been investigated in four very recent systematic reviews [100,101,102,103], suggesting a framework serving to interpret OHRQoL impairment in individual patients, or groups of patients, for clinical practice and research purposes [104]. Previous systematic reviews mainly investigated OHRQoL in specific conditions, or a group of related conditions [103, 105].

A very recent systematic review suggested that OHRQoL in older age predicted global ratings of oral health from 16.4 to 80.2 of variance in relation to the different tools used to evaluate quality of life [106]. The oral items most frequently associated with the hospitalization outcome were difficulties in swallowing/masticatory function, therefore altogether related to oropharyngeal dysphagia, that lack previous systematic review/meta-analytical evidence. Finally, only two oral health items were found to be associated with falls, namely number of teeth (oral health status deterioration category) and dry mouth (chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders category), again lacking previous systematic review/meta-analytical evidence.

Various possible pathways have been suggested to explain the relationship between oral health and adverse health-related outcomes in older age. In particular, a reduced number of teeth, difficulties in chewing, lower occlusal force/masticatory function, and dry mouth were the oral health indicators most frequently associated with an increased risk of death, physical frailty, functional disability, and falls. The first plausible pathway taking into account these oral indicators and mortality/physical frailty/functional disability/falls is the impact of poor oral health on nutrition, food intake and selection. Among older people with a reduced number of teeth, there is an increased tendency to consume processed food versus raw healthy food, and hence a higher likelihood of inadequate nutrition [19, 107]. Furthermore, the impact of a reduced number of teeth on OHRQoL and multimorbidity [104, 108], may influence the risk of mortality. Nutritional status also appeared to mediate the association between oral health and frailty [110, 111], owing to difficulties in eating. Changes in nutrition intake and malnutrition are also risk factors for dementia and stroke [111, 112]. In particular, tooth loss due to periodontal disease and irregular tooth brushing was associated with a doubled risk of AD [113] and a higher risk of dementia [114]. These diseases and systemic condition such as frailty were the major causes of functional disability in older age. Moreover, there was a cross-sectional association between oral frailty and malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults [59], and the interplay among oral health indicators, nutrition, and frailty supported the novel constructs of oral frailty [8,9,10] and nutritional frailty [110]. In particular, in a very recent Italian population-based study, older people with nutritional frailty, firstly defined as a feature of vulnerable older adults, characterized by loss of weight, muscle mass, and strength (sarcopenia), making individuals susceptible to functional disability [115], were at higher risk for all-cause mortality than those with physical frailty, nutritional imbalance (i.e., two or more of the following: low body mass index, low skeletal muscle index, 58 ≥ 2.3 g/day sodium intake, < 3.35 g/day potassium intake, and < 9.9 g/day iron intake), and cognitive frailty [116]. Moreover, the loss of occlusion due to not using dentures after losing teeth may result in poor functional balance [117], a well-known risk factor for falls [118], and these functional declines may explain the increased risk of falls among subjects with poor dental occlusion. Finally, for the suggested link between dry mouth and falls, a possible underlying mechanism could be that some drugs are associated with dry mouth [119], and patients treated with such medications are more likely to suffer falls [120].

The second possible link of tooth loss to mortality, physical frailty, and functional disability is the inflammatory pathway, where infectious agents, such as Streptococcus sanguinis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, play an important role in oral health, possibly exerting direct effects contributing to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and thrombosis [121]. On the other hand, periodontal infection/inflammation is a major reason for eventual tooth loss, and tooth loss is a direct marker of a higher level of periodontal inflammation. Therefore, this increasing cumulative inflammation load caused by oral bacterial infections may increase the risk of mortality, in particular due to its adverse impact on the cardiovascular system [30]. A general susceptibility to inflammation with the early onset of inflammation-driven tooth loss or damaged hip or knee joints may also result in higher mortality than in normal populations [122]. Moreover, a relationship between inflammation and frailty has been suggested [123], and the inflammatory status may increase oxidative stress and insulin resistance, reducing the muscle capacity to synthesize proteins [124], thereby increasing the risk of functional disability in older age.

Difficulties in chewing and lower occlusal force/masticatory function were other oral health predictors associated with mortality, physical frailty, and functional decline identified in the present systematic review. At present, only one operational definition of oral frailty has been introduced, by Tanaka and colleagues [59], based on the identification of six oral health items (i.e., number of teeth, masticatory function, difficulties in chewing, oral diadochokinesis, tongue pressure, and difficulties in swallowing) showing an increased risk of physical frailty, sarcopenia, functional disability, and all-cause mortality. The first three oral items suggested by this operational definition are among the indicators mostly identified in the present systematic review (i.e., number of teeth, masticatory function, and difficulties in chewing). Another possible definition of oral frailty was that encompassing difficulty in chewing associated with age-related changes in swallowing (presbyphagia) [8,9,10]. Therefore, sarcopenia, a progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder involving the accelerated loss of muscle mass and function, could be the connecting link, possibly describing a novel frailty phenotype. To date, sarcopenia is recognized as a whole-body process also affecting masticatory and swallowing muscles (sarcopenic dysphagia) [125]. A reduced nutrient intake in older individuals is directly or indirectly associated with a progressive loss of muscle mass and a decline of oral functions, and coordination capabilities, all of which partly or jointly affect the intricate process of swallowing/eating [126]. With links to both oral frailty and nutritional frailty [8, 100], sarcopenia could share a bidirectional relationship with cognition, producing muscle dysfunction, slow gait, and cognitive dysfunction [127, 128]. Furthermore, the oral health indicators most frequently associated with the hospitalization outcome (i.e., difficulties in swallowing/masticatory function) also encompassed the conditions oropharyngeal dysphagia/sarcopenic dysphagia. Finally, sarcopenia may also be an underlying factor explaining the oral health-falls link because it can cause both swallowing disorders and an increased risk of falls [120].

The link between poor oral health and adverse health-related outcomes may also have some underlying psychosocial factors that should be explored. For example, the social effects of oral health deterioration and its impact on OHRQoL [129], given that loneliness could contribute to the development of frailty [130], mortality [131], and functional disability [132]. However, in older age, for the link between oral health indicators and OHRQoL, we must also take into account the other three dimensions (i.e., orofacial pain, orofacial appearance, and oral function) to better interpret OHRQoL impairment in specific groups of patients [104]. Finally, LLD may affect mortality [133], frailty [134], functional disability [135], OHRQoL [136], hospitalization [137], falls [138], and oral health status [139]. In particular, LLD is frequently associated with poor oral hygiene, a cariogenic diet, diminished salivary flow, rampant dental decay, advanced periodontal disease, and oral dysesthesias [139].

In the present systematic review, owing to the heterogeneity of different variables in oral health assessment and the evaluation of the different adverse health-related outcomes, a quantitative meta-analysis might be unreliable. Some other limitations of the present systematic review should also be considered. Firstly, the study designs were different in the selected studies. The statistical survey of oral factors associated with different adverse health-related outcomes, even using the same definition, was different among the studies, in terms of the rating tools used and the definition of the oral items. Secondly, the number of oral items and the sample size varied between studies. Given the original heterogeneous labeling, we subjectively grouped oral health indicators in four separate categories, driven by the oral health items found in the reviewed studies, with some degree of overlap between these categories (i.e., deterioration of oral motor skills and chewing, swallowing, and saliva disorders).

Conclusion

The present systematic review highlights the importance of oral health as a predictor of several adverse health-related outcomes in older age and shows that the use of oral health indicators in health surveys and clinical practices when conducting a comprehensive clinical oral examination is not currently adequate. In fact, oral health is a part of an individual’s general health status, and a multidisciplinary approach is needed to assess the contribution of oral health measures to specific conditions. On May 27, 2021, the World Health Assembly passed its first-ever resolution on oral health, recognizing it as an issue of global concern, and urging member states to address causes of oral disease, particularly as they overlap with other non-communicable diseases (diets with a high sugar and alcohol content, a smoking habit), and to enable better access to dental care [140]. The number of teeth may serve as a good marker for general health, reflecting the net accumulation of experiences over time, from poor hygiene habits to the occurrence of caries, periodontal diseases, and trauma. Furthermore, routine oral health assessment could pose several challenges in non-gerodontologic settings. In fact, dentists’ conceptions of good healthcare were in line with the conceptualization of patient-centered care; however, inadequate reimbursement and limited resources and time were the most important barriers to providing good care, while one of the most important facilitators was healthcare providers’ attitude and motivation [141]. The tooth count is clinically friendly information that can be easily retrieved during the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) of older people. This oral health indicator may provide useful insights supporting the design of the most appropriate intervention, i.e., the maintenance and/or improvement of oral function and nutritional status. In the near future, oral deficits could be used to integrate the CGA, so as to measure the contribution of oral diseases to frailty and other adverse health-related outcomes in older age. Maintaining or increasing oral function may be associated with an improvement of dietary and functional status in older people and may be implicated in reducing the risk of mortality and of the development of frailty and other major adverse health-related outcomes.

References

Partridge L, Deelen J, Slagboom PE. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature. 2018;561:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0457-8.

Theou O, Rockwood MRH, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Disability and co-morbidity in relation to frailty: how much do they overlap? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:e1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.001.

Baniasadi K, Armoon B, Higgs P, Bayat AH, Mohammadi Gharehghani MA, Hemmat M, Fakhri Y, Mohammadi R, Fattah Moghaddam L, Schroth RJ. The association of oral health status and socio-economic determinants with oral health-related quality of life among the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2021;19:153–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/idh.12489.

Slashcheva LD, Karjalahti E, Hassett LC, Smith B, Chamberlain AM. A systematic review and gap analysis of frailty and oral health characteristics in older adults: a call for clinical translation. Gerodontology. 2021;38:338–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12577.

Takahashi M, Maeda K, Wakabayashi H. Prevalence of sarcopenia and association with oral health-related quality of life and oral health status in older dental clinic outpatients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:915–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13279.

Gil-Montoya JA, Sánchez-Lara I, Carnero-Pardo C, Fornieles-Rubio F, Montes J, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral hygiene in the elderly with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:642–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14697.

Ahmadi B, Alimohammadian M, Yaseri M, Majidi A, Boreiri M, Islami F, Poustchi H, Derakhshan MH, Feizesani A, Pourshams A, Abnet CC, Brennan P, Dawsey SM, Kamangar F, Boffetta P, Sadjadi A, Malekzadeh R. Multimorbidity: Epidemiology and risk factors in the Golestan cohort study, Iran: a cross-sectional analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95: e2756. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002756.

Dibello V, Zupo R, Sardone R, Lozupone M, Castellana F, Dibello A, Daniele A, De Pergola G, Bortone I, Lampignano L, Giannelli G, Panza F. Oral frailty and its determinants in older age: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:E507–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00143-4.

Watanabe Y, Okada K, Kondo M, Matsushita T, Nakazawa S, Yamazaki Y. Oral health for achieving longevity. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:526–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13921.

Parisius KGH, Wartewig E, Schoonmade LJ, Aarab G, Gobbens R, Lobbezoo F. Oral frailty dissected and conceptualized: a scoping review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;100:104653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2022.104653.

Dibello V, Lozupone M, Manfredini D, Dibello A, Zupo R, Sardone R, Daniele A, Lobbezoo F, Panza F. Oral frailty and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:2149–53. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.310672.

Liccardo D, Cannavo A, Spagnuolo G, Ferrara N, Cittadini A, Rengo C, Rengo G. Periodontal Disease: A risk factor for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061414.

Humphrey LL, Fu R, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Helfand M. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2079–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0787-6.

Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1465–82. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2006.060010.

Wang CJ, McCauley LK. Osteoporosis and periodontitis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14:284–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-016-0330-3.

Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:547–58. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.13.4.547.

Beukers NGFM, Su N, Loos BG, van der Heijden GJMG. Lower number of teeth is related to higher risks for ACVD and death-systematic review and meta-analyses of survival data. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8: 621626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.621626.

Jansson L, Kalkali H, Niazi FM. Mortality rate and oral health - a cohort study over 44 years in the county of Stockholm. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76:299–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2018.1423576.

Polzer I, Schwahn C, Völzke H, Mundt T, Biffar R. The association of tooth loss with all-cause and circulatory mortality. Is there a benefit of replaced teeth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:333–51.

Sjögren P, Wårdh I, Zimmerman M, Almståhl A, Wikström M. Oral care and mortality in older adults with pneumonia in hospitals or nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2109–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14260.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Cardiovascular health study collaborative research group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. NIH 2018 (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools).

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Haugh MC, Henry D, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Leng G, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, Middleton P, Mrukowicz J, O’Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schünemann HJ, Edejer T, Varonen H, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Zaza S, GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-4-38.

Aida J, Kondo K, Yamamoto T, Hirai H, Nakade M, Osaka K, Sheiham A, Tsakos G, Watt RG. Oral health and cancer, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality of Japanese. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1129–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034511414423.

Castrejón-Pérez RC, Borges-Yáñez SA, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Avila-Funes JA. Oral health conditions and frailty in Mexican community-dwelling elderly: a cross sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:773. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-773.

Aida J, Kondo K, Hirai H, Nakade M, Yamamoto T, Hanibuchi T, Osaka K, Sheiham A, Tsakos G, Watt RG. Association between dental status and incident disability in an older Japanese population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:338–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03791.x.

Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Misawa J, Hirai H, Nakade M, Aida J, Kondo N, Kawachi I, Hirata Y. Dental status and incident falls among older Japanese: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001262.

Linden GJ, Linden K, Yarnell J, Evans A, Kee F, Patterson CC. All-cause mortality and periodontitis in 60–70-year-old men: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:940–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01923.x.

Schwahn C, Polzer I, Haring R, Dörr M, Wallaschofski H, Kocher T, Mundt T, Holtfreter B, Samietz S, Völzke H, Biffar R. Missing, unreplaced teeth and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1430–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.061.

de Andrade FB, Lebrão ML, Santos JL, Duarte YA. Relationship between oral health and frailty in community-dwelling elderly individuals in Brazil. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:809–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12221.

Ansai T, Takata Y, Yoshida A, Soh I, Awano S, Hamasaki T, Sogame A, Shimada N. Association between tooth loss and orodigestive cancer mortality in an 80-year-old community-dwelling Japanese population: a 12-year prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:814. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-814.

Hayasaka K, Tomata Y, Aida J, Watanabe T, Kakizaki M, Tsuji I. Tooth loss and mortality in elderly Japanese adults: effect of oral care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:815–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12225.

Komulainen K, Ylöstalo P, Syrjälä AM, Ruoppi P, Knuuttila M, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Determinants for preventive oral health care need among community-dwelling older people: a population-based study. Spec Care Dent. 2014;34:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12021.

Hu HY, Lee YL, Lin SY, Chou YC, Chung D, Huang N, Chou YJ, Wu CY. Association between tooth loss, body mass index, and all-cause mortality among elderly patients in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94: e1543. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001543.

Chen YT, Shih CJ, Ou SM, Hung SC, Lin CH, Tarng DC, Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:223.

Hirotomi T, Yoshihara A, Ogawa H, Miyazaki H. Number of teeth and 5-year mortality in an elderly population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:226–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12146.

de Barros LimaMartins AM, Nascimento JE, Souza JG, Sales MM, Jones KM, e Ferreira EF. Associations between oral disorders and the quality of life of older adults in Brazil. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:446–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12489.

Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Sato N, Sato M, Taylor GW, Ansai T, Ono T, Miyazaki H. Maximum bite force at age 70 years predicts all-cause mortality during the following 13 years in Japanese men. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:565–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12401.

Koyama S, Aida J, Kondo K, Yamamoto T, Saito M, Ohtsuka R, Nakade M, Osaka K. Does poor dental health predict becoming homebound among older Japanese? BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-016-0209-9.

Lo YT, Wahlqvist ML, Chang YH, Lee MS. Combined effects of chewing ability and dietary diversity on medical service use and expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;64:1187–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14150.

Iinuma T, Arai Y, Takayama M, Abe Y, Ito T, Kondo Y, Hirose N, Gionhaku N. Association between maximum occlusal force and 3-year all-cause mortality in community-dwelling elderly people. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-016-0283-z.

Komiyama T, Ohi T, Miyoshi Y, Murakami T, Tsuboi A, Tomata Y, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y. Association between tooth loss, receipt of dental care, and functional disability in an elderly Japanese population: the Tsurugaya project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2495–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14390.

Laudisio A, Gemma A, Fontana DO, Rivera C, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Incalzi RA. Self-reported masticatory dysfunction and mortality in community dwelling elderly adults: a 9-year follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2503–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14331.

Bidinotto AB, Santos CM, Tôrres LH, de Sousa MD, Hugo FN, Hilgert JB. Change in quality of life and its association with oral health and other factors in community-dwelling elderly adults-a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2533–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14482.

Castrejón-Pérez RC, Jiménez-Corona A, Bernabé E, Villa-Romero AR, Arrivé E, Dartigues JF, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Borges-Yáñez SA. Oral disease and 3-year incidence of frailty in Mexican older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:951–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw201.

Watanabe Y, Hirano H, Arai H, Morishita S, Ohara Y, Edahiro A, Murakami M, Shimada H, Kikutani T, Suzuki T. Relationship between frailty and oral function in community-dwelling elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14355.

Okura M, Ogita M, Yamamoto M, Nakai T, Numata T, Arai H. Self-assessed kyphosis and chewing disorders predict disability and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:550e1–6.

Matsuyama Y, Aida J, Watt RG, Tsuboya T, Koyama S, Sato Y, Kondo K, Osaka K. Dental status and compression of life expectancy with disability. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1006–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034517713166.

Lund Håheim L, Rønningen KS, Enersen M, Olsen I. The predictive role of tooth extractions, oral infections, and hs-c-reactive protein for mortality in individuals with and without diabetes: a prospective cohort study of a 12 1/2-year follow-up. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:9590740. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9590740.

Veisa G, Tasmoc A, Nistor I, Segall L, Siriopol D, Solomon SM, Donciu MD, Voroneanu L, Nastasa A, Covic A. The impact of periodontal disease on physical and psychological domains in long-term hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:1261–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-017-1571-5.

Kamdem B, Seematter-Bagnoud L, Botrugno F, Santos-Eggimann B. Relationship between oral health and Fried’s frailty criteria in community-dwelling older persons. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0568-3.

Rapp L, Sourdet S, Vellas B, Lacoste-Ferré MH. Oral health and the frail elderly. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6:154–60. https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2017.9.

Ramsay SE, Papachristou E, Watt RG, Tsakos G, Lennon LT, Papacosta AO, Moynihan P, Sayer AA, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG. Influence of poor oral health on physical frailty: a population-based cohort study of older British men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:473–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15175.

Yamanashi H, Shimizu Y, Higashi M, Koyamatsu J, Sato S, Nagayoshi M, Kadota K, Kawashiri S, Tamai M, Takamura N, Maeda T. Validity of maximum isometric tongue pressure as a screening test for physical frailty: cross-sectional study of Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:240–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13166.

Iwasaki M, Kimura Y, Sasiwongsaroj K, Kettratad-Pruksapong M, Suksudaj S, Ishimoto Y, Chang NY, Sakamoto R, Matsubayashi K, Songpaisan Y, Miyazaki H. Association between objectively measured chewing ability and frailty: a cross-sectional study in central Thailand. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:860–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13264.

Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Sato N, Sato M, Minagawa K, Shimada M, Nishimuta M, Ansai T, Yoshitake Y, Ono T, Miyazaki H. A 5-year longitudinal study of association of maximum bite force with development of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12578.

Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Sato M, Minagawa K, Shimada M, Nishimuta M, Ansai T, Yoshitake Y, Miyazaki H. Dentition status and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:256–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13170.

Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Hirano H, Kikutani T, Watanabe Y, Ohara Y, Furuya H, Tetsuo T, Akishita M, Iijima K. Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:1661–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx225.

Mochida Y, Yamamoto T, Fuchida S, Aida J, Kondo K. Does poor oral health status increase the risk of falls?: The JAGES Project Longitudinal Study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0192251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192251.

Michel A, Vérin E, Gbaguidi X, Druesne L, Roca F, Chassagne P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in community-dwelling older patients with dementia: prevalence and relationship with geriatric parameters. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:770–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.04.011.

Komiyama T, Ohi T, Miyoshi Y, Murakami T, Tsuboi A, Tomata Y, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y. Relationship between status of dentition and incident functional disability in an elderly Japanese population: prospective cohort study of the Tsurugaya project. J Prosthodont Res. 2018;62:443–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2018.04.003.

Ohi T, Komiyama T, Miyoshi Y, Murakami T, Tsuboi A, Tomata Y, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y. The association between bilateral maximum occlusal force and all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older adults: the Tsurugaya project. J Prosthodont Res. 2020;64:289–95. https://doi.org/10.1136/10.1016/j.jpor.2018.04.003.

Klotz AL, Tauber B, Schubert AL, Hassel AJ, Schröder J, Wahl HW, Rammelsberg P, Zenthöfer A. Oral health-related quality of life as a predictor of subjective well-being among older adults-a decade-long longitudinal cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:631–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12416.

Jukic Peladic N, Orlandoni P, Dell’Aquila G, Carrieri B, Eusebi P, Landi F, Volpato S, Zuliani G, Lattanzio F, Cherubini A. Dysphagia in nursing home residents: management and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:147–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.07.023.

Shiraishi A, Yoshimura Y, Wakabayashi H, Tsuji Y, Shimazu S, Jeong S. Impaired oral health status on admission is associated with poor clinical outcomes in post-acute inpatients: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:2677–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.020.

da Mata C, Allen PF, McKenna GJ, Hayes M, Kashan A. The relationship between oral-health-related quality of life and general health in an elderly population: a cross-sectional study. Gerodontology. 2019;36:71–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12384.

Hägglund P, Koistinen S, Olai L, Ståhlnacke K, Wester P, Levring JE. Older people with swallowing dysfunction and poor oral health are at greater risk of early death. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019;47:494–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12491.

Ohi T, Komiyama T, Miyoshi Y, Murakami T, Tsuboi A, Tomata Y, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y. Maximum occlusal force and incident functional disability in older adults: the Tsurugaya project. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018;3:195–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084418761329.

Komiyama T, Ohi T, Tomata Y, Tanji F, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y. Dental status is associated with incident functional disability in community-dwelling older japanese: a prospective cohort study using propensity score matching. J Epidemiol. 2020;30:84–90. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20180203.

Hoshino D, Watanabe Y, Edahiro A, Kugimiya Y, Igarashi K, Motokawa K, Ohara Y, Hirano H, Myers M, Hironaka S, Maruoka Y. Association between simple evaluation of eating and swallowing function and mortality among patients with advanced dementia in nursing homes: 1-year prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;87: 103969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.103969.

Valdez E, Wright FAC, Naganathan V, Milledge K, Blyth FM, Hirani V, Le Couteur DG, Handelsman DJ, Waite LM, Cumming RG. Frailty and oral health: findings from the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Gerodontology. 2020;37:28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12438.

Espinosa-Val MC, Martín-Martínez A, Graupera M, Arias O, Elvira A, Cabré M, Palomera E, Bolívar-Prados M, Clavé P, Ortega O. Prevalence, risk factors, and complications of oropharyngeal dysphagia in older patients with dementia. Nutrients. 2020;12:863. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030863.

Yuan JQ, Lv YB, Kraus VB, Gao X, Yin ZX, Chen HS, Luo JS, Zeng Y, Mao C, Shi XM. Number of natural teeth, denture use and mortality in Chinese elderly: a population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01084-9.

Yokota J, Ogawa Y, Takahashi Y, Yamaguchi N, Onoue N, Shinozaki T, Kohzuki M. Dysphagia worsens short-term outcomes in patients with acute exacerbation of heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2020;35:1429–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-020-01617-w.

Oliveira EJP, Alves LC, Santos JLF, Duarte YAO, Andrade FBD. Edentulism and all-cause mortality among Brazilian older adults 11-years follow-up. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e046. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0046.

Tanji F, Komiyama T, Ohi T, Hattori Y, Watanabe M, Lu Y, Tsuji I. The association between number of remaining teeth and maintenance of successful aging in Japanese older people: a 9-year longitudinal study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;252:245–52. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.252.245.

Hakeem FF, Bernabé E, Fadel HT, Sabbah W. Association between oral health and frailty among older adults in Madinah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:975–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1419-z.

Zhang Y, Ge M, Zhao W, Hou L, Xia X, Liu X, Zuo Z, Zhao Y, Yue J, Dong B. Association between number of teeth, denture use and frailty: findings from the West China health and aging trend study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:423–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1346-z.

Hironaka S, Kugimiya Y, Watanabe Y, Motokawa K, Hirano H, Kawai H, Kera T, Kojima M, Fujiwara Y, Ihara K, Kim H, Obuchi S, Kakinoki Y. Association between oral, social, and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89: 104105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104105.

Ogawa M, Satomi-Kobayashi S, Yoshida N, Tsuboi Y, Komaki K, Nanba N, Izawa KP, Sakai Y, Akashi M, Hirata KI. Relationship between oral health and physical frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol. 2021;77:320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.07.016.

Morishita S, Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Edahiro A, Motokawa K, Shirobe M, Furuya J, Watanabe Y, Suga T, Kanehisa Y, Ohuchi A, Hirano H. Relationship between mortality and oral function of older people requiring long-term care in rural areas of japan a four-year prospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041723.

Saito M, Shimazaki Y, Nonoyama T, Tadokoro Y. Association of oral health factors related to oral function with mortality in older Japanese. Gerodontology. 2021;38:166–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12508.

Liljestrand JM, Salminen A, Lahdentausta L, Paju S, Mäntylä P, Buhlin K, Tjäderhane L, Sinisalo J, Pussinen PJ. Association between dental factors and mortality. Int Endod J. 2021;54:672–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13458.

Bengtsson VW, Persson GR, Berglund JS, Renvert S. Periodontitis related to cardiovascular events and mortality: a long-time longitudinal study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:4085–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03739-x.

Noetzel N, Meyer AM, Siri G, Pickert L, Heeß A, Verleysdonk J, Benzing T, Pilotto A, Barbe AG, Polidori MC. The impact of oral health on prognosis of older multimorbid inpatients: the 6-month follow up MPI oral health study (MPIOH). Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:263–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00427-7.

Velázquez-Olmedo LB, Borges-Yáñez SA, Andrade Palos P, García-Peña C, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Sánchez-García S. Oral health condition and development of frailty over a 12-month period in community-dwelling older adults. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01718-6.

Kotronia E, Brown H, Papacosta AO, Lennon LT, Weyant RJ, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE. Oral health and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory mortality in older people in the UK and USA. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95865-z.

Takeuchi N, Sawada N, Ekuni D, Morita M. Oral factors as predictors of frailty in community-dwelling older people: a prospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031145.

Kotronia E, Brown H, Papacosta O, Lennon LT, Weyant RJ, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE. Oral health problems and risk of incident disability in two studies of older adults in the United Kingdom and the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70:2080–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17792.

Ohara Y, Kawai H, Shirobe M, Iwasaki M, Motokawa K, Edahiro A, Kim H, Fujiwara Y, Ihara K, Watanabe Y, Obuchi S, Hirano H. Association between dry mouth and physical frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: the Otassha Study. Gerodontology. 2022;39:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12605.

Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Shirobe M, Kawai H, Edahiro A, Motokawa K, Fujiwara Y, Kim H, Ihara K, Obuchi S, Watanabe Y, Hirano H. Xerostomia as a key predictor of physical frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: a five-year prospective cohort study from The Otassha Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;99: 104608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2021.104608.

Patel J, Wallace J, Doshi M, Gadanya M, Yahya IB, Roseman J, Srisilapanan P. Oral health for healthy ageing. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:E521–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00142-2.

Ramseier CA, Anerud A, Dulac M, Lulic M, Cullinan MP, Seymour GJ, Faddy MJ, Bürgin W, Schätzle M, Lang NP. Natural history of periodontitis: disease progression and tooth loss over 40 years. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:1182–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.1278.

World Health Organization. Working together for health: the World Health Report. 2006. https://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf (Last accessed: February 25, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001262

Koka S, Gupta A. Association between missing tooth count and mortality: a systematic review. J Prosthodont Res. 2018;62:134–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2017.08.00.

Peng J, Song J, Han J, Chen Z, Yin X, Zhu J, Song J. The relationship between tooth loss and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, and coronary heart disease in the general population: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(1):BSR20181773.

Callahan D. The WHO definition of ‘health.’ Stud Hastings Cent. 1973;1:77–88.

John MT. Foundations of oral health-related quality of life. J Oral Rehabil. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13040 [Online ahead of print] https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13040

Oghli I, List T, Su N, Häggman-Henrikson B. The impact of oro-facial pain conditions on oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:1052–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/10.1111/joor.12994.

Larsson P, Bondemark L, Häggman-Henrikson B. The impact of oro-facial appearance on oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:271–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12965.

Su N, van Wijk A, Visscher CM. Psychosocial oral health-related quality of life impact: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:282–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13064.

Schierz O, Baba K, Fueki K. Functional oral health-related quality of life impact: a systematic review in populations with tooth loss. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:256–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12984.

Sekulic S, John MT, Häggman-Henrikson B, Theis-Mahon N. Dental patients’ functional, pain-related, aesthetic, and psychosocial impact of oral conditions on quality of life-project overview, data collection, quality assessment, and publication bias. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:246–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13045.

Reissmann DR, Dard M, Lamprecht R, Struppek J, Heydecke G. Oral health-related quality of life in subjects with implant-supported prostheses: a systematic review. J Dent. 2017;65:22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2017.08.003.

Azami-Aghdash S, Pournaghi-Azar F, Moosavi A, Mohseni M, Derakhshani N, Kalajahi RA. Oral health and related quality of life in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50:689–700. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i4.5993.

Kossioni AE. The association of poor oral health parameters with malnutrition in older adults: a review considering the potential implications for cognitive impairment. Nutrients. 2018;10:1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111709.

Felton DA. Complete edentulism and comorbid diseases: an update. J Prosthodont. 2016;25:5–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.12350.

Walls AW, Steele JG. The relationship between oral health and nutrition in older people. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:853–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.011.

Zupo R, Castellana F, Bortone I, Griseta C, Sardone R, Lampignano L, Lozupone M, Solfrizzi V, Castellana M, Giannelli G, De Pergola G, Boeing H, Panza F. Nutritional domains in frailty tools: working towards an operational definition of nutritional frailty. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64: 101148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101148.

Ozawa M, Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Hirakawa Y, Doi Y, Hata J, Uchida K, Shirota T, Kitazono T, Kiyohara Y. Self-reported dietary intake of potassium, calcium, and magnesium and risk of dementia in Japanese: the Hisayama Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1515–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04061.x.

Hankey GJ. Nutrition and the risk of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70265-4.

Fang WL, Jiang MJ, Gu BB, Wei YM, Fan SN, Liao W, Zheng YQ, Liao SW, Xiong Y, Li Y, Xiao SH, Liu J. Tooth loss as a risk factor for dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 observational studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:345. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1927-0.

Paganini-Hill A, White SC, Atchison KA. Dentition, dental health habits, and dementia: the Leisure World Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1556–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04064.x.

Bales CW, Ritchie CS. Sarcopenia, weight loss, and nutritional frailty in the elderly. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:309–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102715.

Zupo R, Castellana F, Guerra V, Donghia R, Bortone I, Griseta C, Lampignano L, Dibello V, Lozupone M, Coelho-Júnior HJ, Solfrizzi V, Giannelli G, De Pergola G, Boeing H, Sardone R, Panza F. Associations between nutritional frailty and 8-year all-cause mortality in older adults: the Salus in Apulia Study. J Intern Med. 2021;290:1071–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13384.

Yamaga T, Yoshihara A, Ando Y, Yoshitake Y, Kimura Y, Shimada M, Nishimuta M, Miyazaki H. Relationship between dental occlusion and physical fitness in an elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M616–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/57.9.m616.

American Geriatrics Society. British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:664–72.

Villa A, Wolff A, Narayana N, Dawes C, Aframian DJ, Lynge Pedersen AM, Vissink A, Aliko A, Sia YW, Joshi RK, McGowan R, Jensen SB, Kerr AR, Ekström J, Proctor G. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI: a systematic review of medication-induced salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Dis. 2016;22:365–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12402.

World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2014 Available: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHo-Global-report-on-falls-preventionin-older-age.pdf. Last accessed: February 25, 2022.

Mattila KJ, Valtonen VV, Nieminen MS, Asikainen S. Role of infection as a risk factor for atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:719–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/514570.

Jemt T, Nilsson M, Olsson M, Stenport VF. Associations between early implant failure, patient age, and patient mortality: a 15-year follow-up study on 2,566 patients treated with implant-supported prostheses in the edentulous jaw. Int J Prosthodont. 2017;30:189–97. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.4933.

Soysal P, Stubbs B, Lucato P, Luchini C, Solmi M, Peluso R, Sergi G, Isik AT, Manzato E, Maggi S, Maggio M, Prina AM, Cosco TD, Wu YT, Veronese N. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;31:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.006.

Ali S, Garcia JM. Sarcopenia, cachexia and aging: diagnosis, mechanisms and therapeutic options - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60:294–305. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356760.

Wakabayashi H. Presbyphagia and sarcopenic dysphagia: association between aging, sarcopenia, and deglutition disorders. J Frailty Aging. 2014;3:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1136/10.14283/jfa.2014.8.

Fujishima I, Fujiu-Kurachi M, Arai H, Hyodo M, Kagaya H, Maeda K, Mori T, Nishioka S, Oshima F, Ogawa S, Ueda K, Umezaki T, Wakabayashi H, Yamawaki M, Yoshimura Y. Sarcopenia and dysphagia: position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:91–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13591.

Panza F, Lozupone M, Solfrizzi V, Sardone R, Dibello V, Di Lena L, D’Urso F, Stallone R, Petruzzi M, Giannelli G, Quaranta N, Bellomo A, Greco A, Daniele A, Seripa D, Logroscino G. Different cognitive frailty models and health- and cognitive-related outcomes in older age: from epidemiology to prevention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1136/10.3233/JAD-170963.

Bortone I, Griseta C, Battista P, Castellana F, Lampignano L, Zupo R, Sborgia G, Lozupone M, Moretti B, Giannelli G, Sardone R, Panza F. Physical and cognitive profiles in motoric cognitive risk syndrome in an older population from Southern Italy. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:2565–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14882.

Sischo L, Broder H. Oral health-related quality of life: what, why, how, and future implications. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1264–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034511399918.

Gale CR, Westbury L, Cooper C. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 2017;47:392–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx188.

Rico-Uribe LA, Caballero FF, Martín-María N, Cabello M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Miret M. Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0190033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190033.

Park C, Majeed A, Gill H, Tamura J, Ho RC, Mansur RB, Nasri F, Lee Y, Rosenblat JD, Wong E, McIntyre RS. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294: 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514.

Wei J, Hou R, Zhang X, Xu H, Xie L, Chandrasekar EK, Ying M, Goodman M. The association of late-life depression with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among community-dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215:449–55. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.74.

Soysal P, Veronese N, Thompson T, Kahl KG, Fernandes BS, Prina AM, Solmi M, Schofield P, Koyanagi A, Tseng PT, Lin PY, Chu CS, Cosco TD, Cesari M, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.03.005.

Penninx B, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.279.21.1720.

Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:15–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610200006177.

Sayers SL, Hanrahan N, Kutney A, Clarke SP, Reis BF, Riegel B. Psychiatric comorbidity and greater risk, longer length of stay, and higher hospitalization costs in older adults with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1585–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01368.x.

Iaboni A, Flint AJ. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: a clinical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:484–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.008.

Friedlander AH, Friedlander IK, Gallas M, Velasco E. Late-life depression: its oral health significance. Int Dent J. 2003;53:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00655.x.

Editorial. Putting the mouth back into the (older) body. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:E444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00180-X.

Herrler A, Valerius L, Barbe AG, Vennedey V, Stock S. Providing ambulatory healthcare for people aged 80 and over: views and perspectives of physicians and dentists from a qualitative survey. PLoS ONE. 2022;17: e0272866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272866.

Acknowledgements

We thank the “Salus in Apulia” Research Team. This manuscript is the result of the research work on frailty undertaken by the “Italia Longeva: Research Network on Aging” team, supported by the resources of the Italian Ministry of Health—Research Networks of National Health Institutes. We thank M.V. Pragnell for her precious help as native English language supervisor. All authors have access to all the data reported in this systematic review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VD and FP conceptualized this systematic review. ML, RS, AB, GB, AM, HJC-J, GDP, RS, AD, and ADa contributed to data collection. VD, FL, RS, ML, MP, FS, VS, DM, and FP contributed to data interpretation. All authors contributed to drafting, revising, and approving the submitted paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Dibello, V., Lobbezoo, F., Lozupone, M. et al. Oral frailty indicators to target major adverse health-related outcomes in older age: a systematic review. GeroScience 45, 663–706 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-022-00663-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-022-00663-8