Abstract

Anthropogenic activities in search of livelihood come with its environmental implications. This is in line with the current crusade of the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) target 7 and 13 for effective clean energy access and mitigating the adverse effect of climate change issues. Since the seminal study of Kraft and Kraft (1978) on the nexus between energy and gross national product, there has been no consensus in the extant literature in the last four decades. To this end, the current study applies recent data for the case of Nigeria from 1970 to 2017 on an annual frequency. Modified Wald causality test of Toda-Yamamoto is in conjunction with the recent gradual shift causality test with Fourier approximation for robustness and precision of analysis. Empirical results show the pollutant driven economy as one-way causality is seen running from pollutant emission to economic growth. This suggests that economic growth is driven by dirty energy sources that are from non-renewable energy sources. This is further validated in the pollution haven hypothesis (PHH) confirmed in the study by the causality seen running from foreign direct investment and carbon dioxide emissions. Additionally, the exploration of natural resources also engenders economic expansion in Nigeria. Based on the current study findings, a couple of submissions are made such as the need for a paradigm shift to cleaner energy sources. More so, the need for the adoption of cleaner, eco-system friendlier innovations, and technologies will aid in the attainment of the SDGs of mitigating climate and pollution issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent times, it has been discovered that coal energy consumption is more economical among the sources of energy generation. Thus, its demand for consumption continues to increase considering its cheap availability to its consuming economies. Most if not all of these economies tend to prefer it than other sources like oil and gas. No wonder at the global level, the report from the world coal institute has it that in 2005, coal usage alone accounts for about 25.1% of the total energy derived from fossil fuel (Wolde-Rufael 2010). This achievement is above that of gas which accounts for 20.9% only lower than 34.3% generated from oil. Though Nigeria is not the largest coal consuming economy, it remained the giant economy in Africa which makes it a suitable choice to carry out a developmental study such as this. Despite this esteem position occupied in Africa, Nigeria has not achieved its desire economic prosperity, although the success recorded so far is commendably significant. The trend of GDP growth rate shows that the Nigerian economy has witnessed significant and continuous progress despite various shocks experienced at some point among which is the most recent one that hit the country in 2017 and 2018 for which the effect is still lingering till date. The reality of this was down on the nation as a result of the exit of many consumer-based companies from the economy caused by low demand, a general economic hardship, and a sharp reduction from the FDI inflow as supported by Oladipo (2010). For example, FDI inflow achieved in 2012 stood at about $8.92 billion which reduced by 21 percent to N3.5 billion in 2017.

Furthermore, surprisingly, Nigeria which happened to be the gateway of foreign direct investment (FDI, hereafter) inflow into Africa is gradually losing ground to other emerging actors such as Ghana in the West Africa sub-region and Egypt in the continent. For instance, FDI inflow to Nigeria further dropped to $2.2 billion in 2018 behind Ghana which overtook Nigeria by achieving a sharp increase up to $3.3 billion. This decline is still persisting to date as a result of the fear of uncertainty envisaged by the investors UNCTAD (2018). On the other hand, the report from the United State energy consumption administration (EIA 2018) indicates that in 2013, the share of coal consumption for energy generation in Nigeria was small compared with other components of the biomass and waste sources. In 2016, total energy generation include 28.0 ktoe from coal, 13911.0 ktoe from Natural gas, 114,075.0 ktoe from biofuel and waste, 21,110.0 ktoe, 2.0 ktoe from wind, solar, etc., and 480.0 ktoe from Hydro. In 2018, the total basic energy usage in Nigeria according to the (EIA 2018) report stood at 4.8 quadrillion (British thermal units). Out of this amount, 74 percent was generated from traditional biomass and waste which comprises wood, charcoal, manure, and crop residues. This record prompted the need to carry out an investigation for a single country to confirm the causal direction of its relationship with economic expansion. In addition to the above, Shahbaz et al. (2013) maintain that the coal-led growth nexus is still empirically debatable for single country scenarios.

Against to backdrop, the current study is majorly informed by this claim made by Shahbaz et al. (2013) to invest whether or not coal energy consumption drives the Nigerian economy by adding total resource rent, FDI inflow, and CO2 to argument the model for the case of Nigeria. The enclosure of natural resources became imperative because it forms the largest part of government revenue at least no less than 70 percent of the total. This suggests that omitting the natural resources variable from the growth equation of Nigeria may lead to a model specification error, thus, result in a misleading result. This is conducted with a recent causality test of the Modified Wald causality test of Toda-Yamamoto in conjunction with a gradual shift causality test with Fourier approximation for robustness and precision of analysis. Specifically, this study contributes to existing energy literature by incorporating total resource rent, FDI inflow to overcome any model misspecification problem. Generally, the extant studies focus on the relationship between coal consumption, CO2, and economic growth (Shahbaz et al. 2015; Magazzino et al. 2020; Joshua et al. 2020). More importantly, most of the studies on energy-induced growth nexus in Nigeria were centered on the relationship between electricity usage and economic advancement. Thus, this study set out to break even by using coal energy consumption in place of electricity usage to determine the causal link between the variables of interest.

The rest of this study follows: the “Brief literature and empirical review” section dwells on a review of the related literature. The “Data and methodology pathway” section focuses on the data and methodological procedures adopted while the interpretation and discussion of results are presented in the “Empirical results, interpretations, and discussion” section. Finally, the concluding remarks and policy prescriptions are rendered in “Conclusion and Policy Recommendation” section.

Brief literature and empirical review

The contention to justify the relationship between coal usage and economic expansion is an ongoing one as conflicts in the outcomes of the previous studies abound. Some previous studies maintain that coal is a promoter of economic prosperity while others question this claim. Others advocate for a feedback linkage, the fourth hypothesis stands on neutral ground. The first hypothesis refers to the growth hypothesis is of the opinion that a country where coal is consumed will experience a drastic improvement along its economic expansion path. This assertion is closely supported by proven works of authors such as Jin and Kim (2018), who carry out an empirical panel study for selected non-OECD member countries and OECD economies by adopting the FMOLS estimator. Their overall findings reaffirmed the coal-led growth hypothesis after careful examination of the said hypothesis. The finding further reveals that the series co-move in the distance future only for the non-OECD countries and that coal usage and GDP exhibit an inverse linkage for the non-OECD economies in the distance term. This is consistent with the most recent studies conducted by Saint Akadiri et al. (2019) and Udi et al. (2020) for the South African economy. The outcomes further justified the coal-led growth hypothesis by revealing a one-way link from coal usage to economic prosperity implying that coal usage drives an economic acceleration in South Africa. In another related study, Bekun et al. (2019a, 2019b) adopted the three different approaches to cointegration one of which is Bayer and Hanck (2013) for the South Africa economy. The revelation from the study confirmed a long-run equilibrium between the variables. In addition to this, the result further reaffirmed the key role played by coal usage in promoting economic prosperity in South Africa through the revelation of a one-way link from coal to economic advancement. Other studies that lent their supports to the said hypothesis include Ulucak and Bilgili (2018), Chu et al. (2017), and Bekun et al. (2019b). Sarkodie and Adams (2018) examine a similar case in South African using a linear model and found that coal drives economic prosperity aligning with the work of Wolde-Rufael (2009) for India and Japan. Other supporting studies include (see Shiu and Lam 2004; Yuan et al. 2007; Li et al. 2008; Wolde-Rufael 2004). Apergis and Payne (2010) submit that conservation policy is an anti-economic acceleration, particularly in a coal-driven country. Ziramba (2009) confirms the coal usage-led growth nexus, consistent with the work of (see Shahbaz et al. 2013; Sari et al. 2008; Ewing et al. 2007; Narayan and Smyth 2005, ) and (Thoma 2004; Erol and Yu 1987; Soytas and Sari 2003) for the US, Japan, and Germany economies respectively. This hypothesis maintained that conservation policy is anti-economic progress as such should not be implemented for the coal-driven economy.

Secondly, the conservation hypothesis contends that coal usage demand is the product of economic advancement which renders conservation policy-relevant. Supporting this hypothesis is the study of Jinke et al. (2008) which posits that an expansion in GDP will in turn influence the demand for coal usage in the economies of China and Japan without a reversal reaction. According to them, coal usage in china, in particular, depends on how fast the economy of China is expanding which is applicable to Japan. This is consistent with the work of Govindaraju and Tang (2013) for the Indian economy. The implication of this assertion is that if the economy of China or India is reversed in the growth process, coal usage will follow suit. Reynolds and Kolodziej (2008) studied the former Soviet Union and found that economic progress is the determinant of coal usage, similar to the study of Yuan et al. (2008), Yang (2000a), Jinke et al. (2008), Wolde-Rufael (2010), Etokakpan et al. (2020), Kirikkaleli et al. (2020), Adedoyin et al. (2020a), and Adedoyin et al. (2020b). This hypothesis was reaffirmed for Italy and Malawi by these studies (Soytas and Sari 2003; Jumbe 2004). This is consistent with the works of (Zhang and Xu 2012) and Govindaraju and Tang (2013) for China. Soytas and Sari (2003) also validate the hypothesis for Italy.

Furthermore, third, the feedback hypothesis contends that there is an interdependent reaction between the variables under investigation, thus, conservation policy can hamper the process of economic advancement. This assertion is supported by empirical evidence from the work of Belke et al. (2011) and Fuinhas and Marques (2013) who found a feedback interaction between economic expansion and coal consumption. Wolde-Rufael (2009) discovered that economic expansion and coal consumptions drive each other accordingly for the economies of South Africa and the USA. This is similar in Korea and Taiwan as revealed by the works of Yoo (2006) and Yang (2000) as also applicable to the works of (See Yuan et al. 2008; Yang 2000b). Lee and Chang (2005) posit that economic growth and coal usage promotes each other, similar to the revelation found in Korea by the works of Yuan et al. (2008) and Yoo (2006). Wolde-Rufael (2010) examined the economy of South African and found feedback interaction between the variables as well as the work of Wolde-Rufael (2010) for the US economy. For the economies of India and Taiwan in separate studies, Paul and Bhattacharya (2004) and Yuan et al (2008) discovered a bidirectional link.

Finally, fourth, the neutrality hypothesis stands to assert that the influence of coal usage on growth is either insignificant or uncertain. As a result, conservation policy will function well to keep the economy healthy and dynamic. Studies in support of this claim include Wolde-Rufael (2009) who discovered that the dynamic of coal usage in China and South Korea remains uncertain. He went further to discover a none-causal relationship in South Africa aligning with the work of Yuan et al. (2008) for China. The case is not different in Newzealand where Fatai et al. (2004) discovered a non-causal linkage. This is consistent with the studies (Jinke et al. 2008; Ziramba 2009; Payne 2009). On the other hand, Stern (1993) discovered a non-directional interaction for the US economy. Studies (See Yang 2000a; Sari and Soytas 2004; and Lee and Chang 2005) drew separate stands in respect hypothesis understudied.

Data and methodology pathway

The incorporated variables include real (GDP) which represents economic expansion (constant 2010, US$), total natural resource rent (TNR), FDI inflow (FDI), coal consumption (COAL), and CO2 emission (CO2). This study intends to extract time series data except for COAL from the World Bank Development Indicators (2020) database ranging from 1970 to 2017. The Thomson Reuters DataStream is the source of coal consumption. This study adopts the logarithm values of each of the series in an attempt to achieve the growth effect and eliminate the possible heteroscedasticity problem.

Stationary tests

The need for a stationarity test is majorly informed by a long-standing argument that macroeconomic variables usually drift and remain unstable in nature. Thus, the unit root test is carried out to confirm the point of stationarity of the series Gujarati (2009). This according to Gujarati (2009) will help avoid a misleading obtainable from a spurious estimation. This study, therefore, adopts the ADF (Dickey and Fuller 1981) and PP (Phillips and Perron 1988) for ascertaining this reality.

The widely accepted formula is stated:

Here, εt represents the error correction term that is expected to be while noise process with zero mean and constant variance and time, and t indicates time.

Granger causality tests

The current study first employs the Toda-Yamamoto (TY) causality test to ascertain the flow of causality link between the aforementioned variables. TY causality test is based on the modified Wald test (MWALD). The most important feature of this procedure is that TY approach considers the possibility of non-stationarity and cointegration properties of the series. Thereby, this method helps to minimize the risks of the possible wrong identification of the integrated order of the series (Mavrotas and Kelly 2001). Against this backdrop, the TY approach is superior to the traditional pairwise Granger causality test.

Wolde-Rufael (2004) points out the major idea of this technique as follows “to artificially augment the correct VAR order, k, by the maximal order of integration, says dmax.” After that, the need to estimate a (k + dmax) th order of VAR and to ignore the last coefficients of the last lagged dmax vector. With this aim, TY procedure provides the usual test statistics which have appropriate asymptotic distribution.

To carry out the TY Grangers non- causality test, we used the following VAR (k + dmax) system equations:

where k stands for the optimal lag order of the VAR model while εit i = 1, 2,...,5 presents the stochastic terms for the models.

In Eq. (2), it is assumed that the intercept term, δ, does not have any structural shifts. In another way, the intercept term is constant over time. Ignoring the existence of structural shifts in the data generating process might cause false rejection of the true null of no causality that has been shown by Enders and Jones (2016). Also, the causality test results biased toward having the over-rejection problem of the null of non-causality when structural breaks are not properly modeled. Hence, it is important to determine the structural shifts and taking them properly into the model to overcome possible misspecification errors.

Using the dummy variables is one of the conventional techniques for modeling structural breaks (Lee and Strazicich 2003; Zivot and Andrews 1992; Perron 1990). Also, the smooth transition technique is used for the gradual changes in structural shifts (Kapetanios et al. 2003; Leybourne et al. 1998). Both techniques require specific information about the structural break date(s) and their functional forms. To overcome these difficulties, Fourier approach is proposed to capture gradual structural shifts (Rodrigues and Robert Taylor 2012; Enders and Lee 2012a, 2012b; Becker et al. 2006).

In a VAR model, to confirm the source of structural breaks and control these breaks are difficult because a structural break in one variable potentially causes a change in other variables (Enders and Jones 2016; Ng and Vogelsang 2002). Recently, Enders and Jones (2016) conduct a Fourier approximation to determine the form of breaks and estimate the number and date of breaks in a VAR specification. Their findings revealed that the traditional Granger causality approach is sensitive to the unit root and cointegration properties of the VAR model. Therefore, the unit root and cointegration test should be checked as a preliminary analysis to apply the traditional Granger causality test. Because the Wald test has non-standard distribution and nuisance parameters, the variables in a VAR model are integrated and/or co-integrated (Dolado and Lütkepohl 1996; Toda and Yamamoto 1995). As we mentioned earlier, to overcome these problems, the TY approach is proposed by Toda and Yamamoto (1995). Next, the Fourier approach is proposed as an extension of the TY approach with gradual changes. The current study also employs Fourier approximation to account for the possibility of gradual shifts in Granger causality analysis.

Modeling the structural shifts, we need to relax the assumption of the intercept parameter δ being constant over time and adjust the VAR model in Eq. (2).

where the intercept terms δ(t) denote ant structural shifts in zt since δ(t) is functions of time. To capture structural breaks as a gradual shift with an unknown number, date, and form of breaks, the Fourier approximation can be defined as follows:

where φ1 and φ2measures the amplitude and displacement of the frequency, respectively. k is a frequency of the approximation. By substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (1), we obtain the following equation:

The structure of the null hypothesis of Eq. (5) is the same it is in Eq. (1). This null hypothesis of Granger non-causality can be tested by using the Wald statistic. However, the recent studies in the Granger causality literature utilize bootstrapping critical values to obtain more robust inferences for the unit root and cointegrating properties of the data (Balcilar et al. 2010; Hacker and Hatemi-J 2006; Shukur and Mantalos 2000). Because of this superior property, this study uses the bootstrap distribution of F-statistics.

Empirical results, interpretations, and discussion

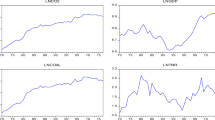

This section presents the empirical finding by carrying out a stationarity test first for the purpose of avoiding spurious regression using the widely accepted conventional ADF and PP unit root tests to determine the stationarity of the variables of interest. The visual graph of the variables of interest was also plotted to view the trended movement of the series. Table 1 proves that GDP exhibits a higher average comparatively. The standard deviation revealed a high level of the dispersion of the series from their means, and that all the series except for the GDP are negatively skewed (Fig. 1). Through its probability value, the Jargue-Bera outcome validates the normal distribution of the series except for RGDP and TRN. The overall outcome from the Pearson’s coefficient correlation in Table 2 shows a positive and significant connection between series. Furthermore, ADF and PP tests as presented in Table 3 show that only FDI inflow and total natural resources rent were stationary before the first differencing. However, at the first difference, all variables became stationary at a 1 percent degree of freedom except for GDP at a 5 percent level of significance.

This study adopted majorly the TY causality test and block exogeneity test to ascertain the causal effect of the variables under study as reported in Table 4. In order to affirm robustness and precision of analysis, the recent gradual shift causality test with Fourier approximation is also employed. Firstly, both analyses are in harmony, and the estimations indicate a non-causal link between GDP and CO2 which suggests that economic expansion is not a promoter of carbon emission in Nigeria contradicting the work of Bekun et al. (2019a, 2019b) for South Africa. The implication is that the growth path of the Nigerian economy is pure and free from carbon emission. Another revelation shows that coal consumption does not Granger cause carbon emission nor induce economic expansion contradicting the finding of Saint Akadiri et al. (2019). This could be linked with the earlier claim recorded in the (EIA 2018) which claimed that the proportion of coal usage in Nigeria for the purpose of energy generation is small. This means that the share of coal usage in Nigeria is too small to significantly induce both economic expansions and to pose environmental degradation. Policymakers and managers of this economy required to channel their effort toward other directions to determine the root cause of carbon emission as coal is discovered not to be a contributor to carbon emission. Interestingly, the findings from this study revealed a non-causal link between FDI inflow and carbon emission which implies that the FDI inflows to Nigeria are pure in nature and dynamic to induce the course of economic progress. This calls for a conscious effort by the managers of the economy to adopt policies that will create both political and macroeconomic investment appealing environment in addition to business incentives that woo more foreign investors into the economy. Thus, strategic policies and business incentives such as a free license for operation, tax holidays, and free land for industrial sitting are highly recommended for the Nigerian economy.

The further empirical result also proves a non-causal link between total natural resources rent and carbon emission. The finding also revealed an uncertain causal direction between coal consumption and economic expansion confirming the neutrality hypothesis in the case of Nigeria. Furthermore, one could intuitively align the outcome of this study with the initial claim made by (EIA 2018) which stresses that the quantity of coal consumption in Nigeria is small, hence not strong enough to drive economic expansion. As expected, the study revealed a one-way causal direction linking from FDI inflow to economic expansion confirming the FDI-led growth nexus as supported by the work of Gungor and Ringim (2017) but contradicting the work of Joshua (2019) for Nigeria. The studies of Joshua (2019) found that FDI does not Granger causes economic expansion during the period under consideration. Since FDI inflow is pure and growth-driven, thus validating the pollution haven hypothesis in Nigeria. Thus, the authority must take note of this. Effective policies should be put in place to attract more foreign investors to enable the country to achieve her desire goal of economic expansion and development. Stability in the macroeconomic environment, such as a stable exchange rate and stable inflation rate, is a key to attracting foreign investors into the economy. Convincingly as expected, the finding revealed a unidirectional link from total natural resources rent to economic acceleration. This needs no logical proof as the Nigerian economy is controlled by natural resources (oil sector). It is imperative to point out here that after the oil boom in the 1970s, there was a paradigm shift from agricultural-intensive to the oil-intensive economy in Nigeria. Thus, earning from natural resources particularly the oil sector constitute the highest revenue base of the economy. This implies that no oil sector, no Nigerian economy which is educative to the authority concern. The implication is that the government must remind itself that achieving economic acceleration in Nigeria lies not just in the earning but proper spending of the revenue accruing from the oil sector; as such, the earning from this sector must be injected into a sensitive investment that could generate higher returns. Second, the outcome from the block exogeneity test is similar to the outcome from the TY Granger causality with a little different. The difference is the revelation of a bidirectional relationship between GDP and CO2 similar to the study of (Sarkodie and Adams 2018; Bekun et al. 2019a). This means that as the economy of Nigeria experiences expansion emission is inevitable and vice versa. This is a task on the path of the researchers and policymakers to investigate the growth-induce factors which also act as a pollutant in the economy in other to address them properly otherwise in the nearest future, economic expansion could turn out to be a curse rather than a blessing to national development. Another different outcome from this method is a unidirectional relationship from FDI to TNR. This suggests that the extraction of natural resources in Nigeria is done in partnership with foreign investors as the local firms are believed to be deficient in technological advancement needed for extraction. The implication is that indigenization policy is not healthy for the economy as a partnership with foreign investors particularly in the area of extraction is required to achieving cleaner extraction of the natural wealth of the nation and by extension achieving economic expansion.

To further drive home, the aforementioned results are the innovation accounting analysis of impulse response function (IRF) which the reaction of each variable on another over an identified forecast horizon period as presented in Fig. 2. The graphical analysis shows the pollutant emission increases at an earlier period and then decreases at one standard deviation shock to the system in the third period, and the same trend is seen in the analysis between coal energy and foreign direct investment. All these interactions indicate that all series are responsive to each other. Thus, the need for caution on the side of policymaker is an insightful policy prescription.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendation

This study seeks to adopt the TY Granger causality and the gradual shift Granger causality test with Fourier approximation tests as the method of estimation to check the flow of causal relationship between coal energy usage and economic advancement in Nigeria. The findings from the study prove that coal energy usage does not Granger cause GDP nor induces carbon emission. This implies that coal consumption is not an important factor in the growth equation of Nigeria as such the authority should look away from coal usage for generating power supply even in the future. The unidirectional link from FDI to economic acceleration and a non-causal effect relationship between FDI and carbon emission illustrates that only cleaner FDI flows to Nigeria and is acting as a strong agent of economic prosperity which is instructive to the policymaker.

The authority concern must as a matter of urgency set up investment appealing macroeconomic policies to woo more investors into the country. Policies and business incentives such as free licenses for operation and tax holidays are viable to influence the decision of foreign investors. Other policies such as a stable exchange rate, stable inflation rate, and a peaceful political atmosphere are critical to inform the investment decision of the foreign investors. One of the key roles of FDI is seen in the extraction of natural resources which is the biggest revenue generation of the nation. This implies that the authority concern must encourage partnership with the foreign companies in the extraction of the natural wealth of the nation against the policy of total indigenization which disfavors the foreign company’s participation. This is connected to the fact that the local industries with their crude technology and knowledge may not be able to extract the resources effectively, therefore, resulting in wastage. Furthermore, a unidirectional link running from total natural resources and economic expansion was revealed by the current study.

Furthermore, this needs no argument as the Nigerian economy relies on the natural endowment majorly in the oil sector. The government of the day should ensure that revenue accrued to this sector must be judiciously utilized or invested especially in the higher return investment to generate the desire for economic expansion. Finally, the finding from the block exogeneity causality revealed a one-way link between economic progress and CO2. This suggests that the pathway to economic expansion in Nigeria is not from the clean energy source; thus, the authority concern must strategize to promptly tackle toxic substances generated through growth by providing proper channels for their discharge in other to avoid future environmental degradation. Neglecting this will be endangering the economy in the future through carbon emission which could eventually turn out to undo the course of economic expansion. A flexible mixed policy is strongly recommended for this economy. Conservation/growth policies could be applied and relax at some points in time depending on the prevailing economic situation. At a higher level of carbon emission signifying serious danger to the environment, the authority concern could relax the growth-inducing policies for a while and to engage in environmental cleansing. Alternatively, the economy could switch to more cleaner energy consumption if energy is known to be the major cause of carbon emission.

References

Adedoyin FF, Gumede MI, Bekun FV, Etokakpan MU, Balsalobre-lorente D (2020a) Modelling coal rent, economic growth and CO2 emissions: Does regulatory quality matter in BRICS economies? Sci Total Environ 710:136284

Adedoyin FF, Alola AA, Bekun FV (2020b) An assessment of environmental sustainability corridor: the role of economic expansion and research and development in EU countries. Sci Total Environ 136726

Apergis N, Payne JE (2010) Coal consumption and economic growth: evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Energy Policy 38(3):1353–1359

Balcilar M, Ozdemir ZA, Arslanturk Y (2010) Economic growth and energy consumption causal nexus viewed through a bootstrap rolling window. Energy Econ 32(6):1398–1410

Bayer C, Hanck C (2013). Combining non‐cointegration tests. Journal of Time series analysis, 34(1):83–95.

Becker R, Enders W, Lee J (2006) A stationarity test in the presence of an unknown number of smooth breaks. J Time Ser Anal 27(3):381–409

Bekun FV, Alola AA, Sarkodie SA (2019a) Toward a sustainable environment: nexus between CO2 emissions, resource rent, renewable and nonrenewable energy in 16-EU countries. Sci Total Environ 657:1023–1029

Bekun FV, Emir F, Sarkodie SA (2019b) Another look at the relationship between energy consumption, carbon dioxide emissions, and economic growth in South Africa. Sci Total Environ 655:759–765

Belke A, Dobnik F, Dreger C (2011) Energy consumption and economic growth: new insights into the cointegration relationship. Energy Econ 33(5):782–789

Chu S, Cui Y, Liu N (2017) The path towards sustainable energy. Nat Mater 16(1):16–22

Dickey DA, Fuller WA (1981) Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica J Econ Soc:1057–1072

Dolado JJ, Lütkepohl H (1996) Making Wald tests work for cointegrated VAR systems. Econ Rev 15(4):369–386

Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2018. http://www.eia.gov/aeo

Enders W, Jones P (2016) Grain prices, oil prices, and multiple smooth breaks in a VAR. Stud Nonlinear Dyn Econ 20(4):399–419

Enders W, Lee J (2012a) A unit root test using a Fourier series to approximate smooth breaks. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 74(4):574–599

Enders W, Lee J (2012b) The flexible Fourier form and Dickey–Fuller type unit root tests. Econ Lett 117(1):196–199

Erol U, Yu ES (1987) On the causal relationship between energy and income for industrialized countries. J Energy Dev:113–122

Etokakpan MU, Adedoyin F, Vedat Y, Bekun FV (2020) Does globalization in Turkey induce increased energy consumption: insights into its environmental pros and cons. Environ Sci Pollut Res

Ewing BT, Sari R, Soytas U (2007) Disaggregate energy consumption and industrial output in the United States. Energy Policy 35(2):1274–1281

Fatai K, Oxley L, Scrimgeour FG (2004) Modelling the causal relationship between energy consumption and GDP in New Zealand, Australia, India, Indonesia, The Philippines and Thailand. Math Comput Simul 64(3-4):431–445

Fuinhas JA, Marques AC (2013) Rentierism, energy and economic growth: the case of Algeria and Egypt (1965–2010). Energy Policy 62:1165–1171

Govindaraju VC, Tang CF (2013) The dynamic links between CO2 emissions, economic growth and coal consumption in China and India. Appl Energy 104:310–318

Gujarati DN (2009) Basic econometrics. Tata McGraw-Hill Education

Gungor H, Ringim SH (2017) Linkage between foreign direct investment, domestic investment and economic growth: evidence from Nigeria. Int J Econ Financ Issues 7(3):97–104

Hacker RS, Hatemi-J A (2006) Tests for causality between integrated variables using asymptotic and bootstrap distributions: theory and application. Appl Econ 38(13):1489–1500

Jin T, Kim J (2018) Coal consumption and economic growth: panel cointegration and causality evidence from OECD and non-OECD countries. Sustainability 10(3):660

Jinke L, Hualing S, Dianming G (2008) Causality relationship between coal consumption and GDP: difference of major OECD and non-OECD countries. Appl Energy 85(6):421–429

Joshua U (2019) An ARDL Approach to the government expenditure and economic growth nexus in Nigeria. Acad J Econ Stud 5(3):152–160

Joshua U, Bekun FV, Sarkodie SA (2020) New insight into the causal linkage between economic expansion, FDI, coal consumption, pollutant emissions and urbanization in South Africa. Environ Sci Pollut Res:1–12

Jumbe CB (2004) Cointegration and causality between electricity consumption and GDP: empirical evidence from Malawi. Energy Econ 26(1):61–68

Kapetanios G, Shin Y, Snell A (2003) Testing for a unit root in the nonlinear STAR framework. J Econ 112(2):359–379

Kirikkaleli D, Adedoyin FF, Bekun FV (2020) Nuclear energy consumption and economic growth in the UK: Evidence from wavelet coherence approach. J Public Aff

Kraft J, Kraft A (1978) On the relationship between energy and GNP. J Energy Dev:401–403

Lee CC, Chang CP (2005) Structural breaks, energy consumption, and economic growth revisited: evidence from Taiwan. Energy Econ 27(6):857–872

Lee J, Strazicich MC (2003) Minimum Lagrange multiplier unit root test with two structural breaks. Rev Econ Stat 85(4):1082–1089

Leybourne SJ, Mills TC, Newbold P (1998) Spurious rejections by Dickey–Fuller tests in the presence of a break under the null. J Econ 87(1):191–203

Li W, Yang K, Peng J, Zhang L, Guo S, Xia H (2008) Effects of carbonization temperatures on characteristics of porosity in coconut shell chars and activated carbons derived from carbonized coconut shell chars. Ind Crop Prod 28(2):190–198

Magazzino C, Bekun FV, Etokakpan MU, Uzuner G (2020) Modeling the dynamic Nexus among coal consumption, pollutant emissions and real income: empirical evidence from South Africa. Environ Sci Pollut Res:1–11

Mavrotas G, Kelly R (2001) Old wine in new bottles: testing causality between savings and growth. Manch Sch 69:97–105

Narayan PK, Smyth R (2005) Electricity consumption, employment and real income in Australia evidence from multivariate Granger causality tests. Energy Policy 33(9):1109–1116

Ng S, Vogelsang TJ (2002) Analysis of vector autoregressions in the presence of shifts in mean. Econ Rev 21(3):353–381

Oladipo OS (2010) Does saving really matter for growth in developing countries? The case of a small open economy. Int Bus Econ Res J 9(4)

Paul S, Bhattacharya RN (2004) Causality between energy consumption and economic growth in India: a note on conflicting results. Energy Econ 26(6):977–983

Payne JE (2009) On the dynamics of energy consumption and output in the US. Appl Energy 86(4):575–577

Perron P (1990) Testing for a unit root in a time series with a changing mean. J Bus Econ Stat 8(2):153–162

Phillips PC, Perron P (1988) Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75(2):335–346

Reynolds DB, Kolodziej M (2008) Former Soviet Union oil production and GDP decline: Granger causality and the multi-cycle Hubbert curve. Energy Econ 30(2):271–289

Rodrigues PM, Robert Taylor AM (2012) The flexible Fourier form and local generalised least squares de-trended unit root tests. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 74(5):736–759

Saint Akadiri S, Bekun FV, Sarkodie SA (2019) Contemporaneous interaction between energy consumption, economic growth and environmental sustainability in South Africa: What drives what? Sci Total Environ 686:468–475

Sari R, Soytas U (2004) Disaggregate energy consumption, employment and income in Turkey. Energy Econ 26(3):335–344

Sari R, Ewing BT, Soytas U (2008) The relationship between disaggregate energy consumption and industrial production in the United States: an ARDL approach. Energy Econ 30(5):2302–2313

Sarkodie SA, Adams S (2018) Renewable energy, nuclear energy, and environmental pollution: accounting for political institutional quality in South Africa. Sci Total Environ 643:1590–1601

Shahbaz M, Khan S, Tahir MI (2013) The dynamic links between energy consumption, economic growth, financial development and trade in China: fresh evidence from multivariate framework analysis. Energy Econ 40:8–21

Shahbaz M, Farhani S, Ozturk I (2015) Do coal consumption and industrial development increase environmental degradation in China and India? Environ Sci Pollut Res 22(5):3895–3907

Shiu A, Lam PL (2004) Electricity consumption and economic growth in China. Energy Policy 32(1):47–54

Shukur G, Mantalos P (2000) A simple investigation of the Granger-causality test in integrated-cointegrated VAR systems. J Appl Stat 27(8):1021–1031

Soytas U, Sari R (2003) Energy consumption and GDP: causality relationship in G-7 countries and emerging markets. Energy Econ 25(1):33–37

Stern DI (1993) Energy and economic growth in the USA: a multivariate approach. Energy Econ 15(2):137–150

Thoma M (2004) Electrical energy usage over the business cycle. Energy Econ 26(3):463–485

Toda HY, Yamamoto T (1995) Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J Econ 66(1-2):225–250

Udi J, Bekun FV, Adedoyin FF (2020) Modeling the nexus between coal consumption, FDI inflow and economic expansion: does industrialization matter in South Africa? Environ Sci Pollut Res:1–12

Ulucak R, Bilgili F (2018) A reinvestigation of EKC model by ecological footprint measurement for high, middle and low income countries. J Clean Prod 188:144–157

UNCTAD, D. (2018). FDI/MNE database.

Wolde-Rufael Y (2004) Disaggregated industrial energy consumption and GDP: the case of Shanghai, 1952–1999. Energy Econ 26(1):69–75

Wolde-Rufael Y (2009) Energy consumption and economic growth: the experience of African countries revisited. Energy Econ 31(2):217–224

Wolde-Rufael Y (2010) Coal consumption and economic growth revisited. Appl Energy 87(1):160–167

World Bank Development Indicators (2020) Retrieved from http://databank.worldbank.org (January 2020)

Yang HY (2000a) A note on the causal relationship between energy and GDP in Taiwan. Energy Econ 22(3):309–317

Yang HY (2000b) Coal consumption and economic growth in Taiwan. Energy Sources 22(2):109–115

Yoo SH (2006) Causal relationship between coal consumption and economic growth in Korea. Appl Energy 83(11):1181–1189

Yuan J, Zhao C, Yu S, Hu Z (2007) Electricity consumption and economic growth in China: cointegration and co-feature analysis. Energy Econ 29(6):1179–1191

Yuan JH, Kang JG, Zhao CH, Hu ZG (2008) Energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from China at both aggregated and disaggregated levels. Energy Econ 30(6):3077–3094

Zhang C, Xu J (2012) Retesting the causality between energy consumption and GDP in China: Evidence from sectoral and regional analyses using dynamic panel data. Energy Econ 34(6):1782–1789

Ziramba E (2009) Disaggregate energy consumption and industrial production in South Africa. Energy Policy 37(6):2214–2220

Zivot E, Andrews DWK (1992) Further evidence on the great crash, the oil-price shock, and the unit-root hypothesis. J Bus Econ Stat 20(1):25–44

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Nicholas Apergis

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joshua, U., Uzuner, G. & Bekun, F.V. Revisiting the causal nexus between coal energy consumption, economic growth, and pollutant emission: sorting out the causality. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27, 30265–30274 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09265-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09265-3