Abstract

Objectives

Specialized treatment programs for juvenile sex offenders (JSOs) are commonly used in juvenile justice systems. Despite their popularity, the evidence base for the effectiveness of these specialized programs is limited in both scope and quality. This systematic review and meta-analysis updates previous meta-analyses while focusing on studies of relatively high methodological quality.

Methods

A vigorous literature search guided by explicit inclusion criteria was conducted. Descriptive and statistical information for each eligible study was coded independently by two coders and disagreements resolved by consensus. Odds ratio effect sizes were computed for sexual recidivism and general recidivism outcomes. Mean effect sizes and their heterogeneity were examined with both fixed and random effects meta-analysis.

Results

Only eight eligible studies were located, seven of which were quasi-experiments. The mean effect size for the seven studies reporting sexual recidivism favored treatment but was not statistically significant (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.40, 1.36). The mean effect size for general recidivism was significant and also favored treatment (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.42, 0.81).

Conclusions

Remarkably little methodologically credible research has been conducted on specialized programs for JSOs despite their prevalence. The best available evidence does not support a confident conclusion that they are more effective for reducing sexual recidivism than general treatment as usual in juvenile justice systems. Future research should not only use randomized designs but should also distinguish generalist offenders who are at low risk of sexual recidivism from specialist offenders who are at higher risk of committing future sexual offenses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Beginning in the late 1980s the label “juvenile sex offender” (JSO) became increasingly prevalent in popular discourse (Harris and Socia 2016) and a general dearth of research on JSOs allowed public fears and misperceptions to guide the development of restrictive policies and treatments targeting this population of youth (Becker and Hicks 2003; Chaffin 2008; Chaffin and Bonner 1998; Dwyer and Letourneau 2011). Such restrictive practices include trying JSOs as adults, prescribing minimum sentences, allowing public access to juvenile offense records, and mandating JSO treatment.

Letourneau and Miner (2005) argue that these actions are rooted in three unfounded assumptions: (1) there is an epidemic of juvenile offending that includes sexual offending; (2) JSOs have more in common with adult sex offenders than with other juvenile offenders; and (3) without specialized sex offender treatment, JSOs are at high risk of committing further sexual offenses. Although there was little scientific data to evaluate these assumptions at the time when most policies targeting JSOs were enacted, Chaffin (2008) has since observed that “an increasing accumulation of data” indicates that the justifications are “no longer merely unproven or unexamined assumptions, but are flatly at odds with the facts as we know them” (p. 111).

Contrary to beliefs about an epidemic of juvenile offending, data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) show that rates of serious violent offenses committed by juveniles have declined markedly over the past two decades (Oudekerk and Morgan 2016). Furthermore, drawing a firm distinction between JSOs and other juvenile offenders only seems to be warranted in a small proportion of cases. Seto and Lalumiere (2010) distinguished two theoretical models for understanding JSOs: (1) a generalist model that assumes JSOs commit sexual offenses as part of a broader pattern of delinquency, and (2) a specialist model that assumes JSOs are “a distinct group of offenders whose sexual offenses are explained by special factors that differ from the factors that explain the offenses of other juvenile delinquents” (p. 527).

Seto and Lalumiere tested these models with a meta-analysis of 59 studies comparing adolescent males who committed sexual offenses (N = 3855) to those who committed nonsexual offenses (N = 13,393). Their findings highlighted both differences and similarities between these two groups, leading Pullman and Seto (2012) to suggest that the majority of JSOs are generalist offenders who happen to commit a sexual offense, whereas a small minority of JSOs are specialist offenders with elevated risk for further sexual offending. The belief by many policymakers that all JSOs are specialist offenders who pose a serious threat to the public (Becker and Hicks 2003) gives rise to the third assumption that underlies restrictive practices for handling JSOs: the idea that specialized treatment is necessary to prevent JSOs from committing future sexual offenses.

This assumption is also not supported by current research, which indicates that few JSOs are at risk for sexual recidivism. In a meta-analysis of 106 studies measuring recidivism among juveniles charged with a sexual offense (N = 33,783), Caldwell (2016) found recidivism rates of approximately 5% for sexual re-offense and a far greater rate of 41% for general nonsexual re-offense within a mean follow-up period of 62 months. In comparison, a meta-analysis of 23 studies measuring sexual recidivism among sexually offending adults (N = 8106) found a recidivism rate of 11.1% within a follow-up period of 5 years (Helmus et al. 2012). These findings indicate that JSOs exhibit a lower sexual recidivism rate than adult sex offenders, although it is low for both. Additionally, JSOs are at far greater risk of recidivating nonsexually than sexually.

Nonetheless, the belief that juveniles who have committed one sexual offense are at risk for future sexual offenses has resulted in a proliferation of specialized treatment programs. The rationale for these programs was solidified more than two decades ago when the 1993 Revised Report from the National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending declared “sexually abusive youth require a specialized response from the justice system which is different from other delinquent populations” (National Adolescent Perpetrator Network 1993, p. 86). Although official guidelines for the treatment of JSOs have recently begun to change (see Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers 2017), sufficient time has not yet passed to determine whether these recommendations will be adopted into practice.

Current evidence indicates that treatment programs for JSOs have focused on sex offenses, have been implemented with groups composed entirely of JSOs, and are generally modeled on specialized treatment programs designed for adult sex offenders (Dwyer and Letourneau 2011). A 2009 survey of community and residential programs for sex offenders revealed that the core treatment targets were, in fact, very similar for programs serving adults and those serving juveniles (McGrath et al. 2010). These targets included arousal control, emotional regulation, family support networks, intimacy/relationship skills, offense responsibility, offense supportive attitudes, problem solving, self-monitoring, social skills training, and victim awareness and empathy.

Questions about the appropriateness of these specialized treatment programs for JSO-labeled youth have inspired a call for rigorous research on their effectiveness (Letourneau and Borduin 2008; Letourneau and Miner 2005). Indeed, Letourneau and Borduin declared that it was an “ethical imperative” that high-quality studies be conducted, as the tendency to ignore both the multiple determinants of juvenile sexual offending and the generally low risk for sexual recidivism may have produced specialized treatments that are inappropriate and/or ineffective for juveniles. The purpose of the systematic review and meta-analysis reported here is to compile and summarize collective findings from the highest quality studies currently available exploring the effects of such treatment programs on JSOs’ sexual and general recidivism.

Previous meta-analyses on effects of specialized JSO programs on recidivism

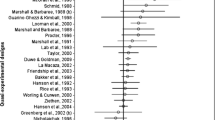

In comparison to the number of studies examining the effects of specialized treatment on the recidivism of adult sex offenders, the comparable body of research on JSOs is modest (Kim et al. 2016). Nonetheless, enough research has been conducted to support prior meta-analyses of treatment effects for JSOs. These meta-analyses have generally reported small to medium treatment effects on both sexual and general recidivism. However, many of the studies included in these meta-analyses have major methodological weaknesses that undermine their ability to generate valid estimates of treatment effects and thus, in turn, undermine the credibility of the conclusions of those meta-analyses (see Table 1 for an overview of studies included in previous meta-analyses as well as their eligibility status for the present meta-analysis).

In the earliest meta-analysis to examine effects of specialized treatment on sexual recidivism among JSOs, Hanson et al. (2002) found a nonsignificant mean odds ratio (OR) of 0.50 favoring treatment across four studies with samples composed exclusively of juveniles. One of the included studies was an RCT that compared the effects of specialized JSO treatment to treatment as usual (Borduin et al. 1990). The remaining three used nonrandom assignment, but reported baseline measures of equivalence between treatment and comparison groups (Guarino-Ghezzi and Kimball 1998; Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000).

Two years later Walker et al. (2004) synthesized findings from studies evaluating the effects of specialized treatment on juveniles’ sexual recidivism rates, self-reported measures of sexual attitudes and behaviors, and measures of arousal in response to deviant sexual stimuli. Among the three studies that reported sexual recidivism outcomes Walker et al. found a small-to-medium mean treatment effect (r = .26). One of their included studies was an RCT (Borduin et al. 1990). The remaining two studies used nonrandom assignment, with one comparing treatment effects between JSOs and juveniles who committed nonsexual offenses (Brannon and Troyer 1991) and the other comparing treatment effects between JSOs who received any of ten possible specialized treatments (Kahn and Chambers 1991).

In a 2005 synthesis of research evaluating specialized treatment for both adults and juveniles who have committed sexual offenses, Lösel and Schmucker found a significant mean treatment effect on sexual recidivism among a subsample of seven studies composed exclusively of juveniles (OR = 2.35, coded so an odds ratio greater than 1.00 indicated a positive outcome). Noting that inclusion criteria for this early meta-analysis were not particularly stringent, the authors subsequently updated their analysis with stricter methodological standards (Schmucker and Lösel 2015). They found a significant mean treatment effect on sexual recidivism (OR = 2.97) for the five studies that focused on juveniles. One study was an RCT that compared specialized JSO treatment with treatment as usual (Borduin et al. 1990) and one was an RCT that compared the effects of two specialized JSO treatments with each other (Borduin et al. 2009). Three used nonrandom assignment, but reported baseline measures of equivalence between treatment and comparison groups (Guarino-Ghezzi and Kimball 1998; Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000).

In what is perhaps the most widely cited meta-analysis on JSO treatment and recidivism, Reitzel and Carbonell (2006) reported a significant mean effect favoring treatment on sexual recidivism (OR = 0.43). Of the nine studies included in their meta-analysis, one was an RCT that compared specialized JSO treatment with treatment as usual (Borduin et al. 1990). Two studies used nonrandom assignment, but reported baseline measures of equivalence between treatment and comparison groups (Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000). One used nonrandom assignment and reported baseline measures for the treatment group only (Cooper and Schmidt 2000), one study did not specify how youth were assigned to treatment and comparison groups (McTavish 1996), and one compared treatment effects between JSOs who committed serious sexual offenses and JSOs who committed less serious sexual offenses (Wieckowski et al. 2003). One research report summarized no original data and only presented a general overview of previously published studies (Borduin and Schaeffer 2001). Finally, two datasets contributing to the meta-analytic sample were obtained from practitioners working in the field with JSOs for which no research design information was available (Hurley 2003; Jeffords 2003).

In the same year that Reitzel and Carbonell (2006) published their meta-analysis, Winokur et al. (2006) synthesized findings from six studies of specialized treatment effects for JSOs, with five studies reporting a sexual recidivism outcome and five reporting a general recidivism outcome. They found a small but significant mean treatment effect on sexual recidivism (g = 0.25) and a larger significant effect on general recidivism (g = 0.47). Of the six studies in their sample, three used nonrandom assignment but reported baseline measures of equivalence (Byrne 1999; Waite et al. 2005; Worling and Curwen 2000). Two studies compared effects for juveniles who completed treatment and those who did not (Barlow 1996; Seabloom et al. 2003) and one examined treatment effects among a single group of juveniles who received specialized treatment from a single agency (Wolk 2005).

Finally, using a meta-analytic sample of studies with adults and juveniles, Hanson et al. (2009) found a significant mean effect favoring treatment on sexual recidivism for the four studies focusing on adolescents (OR = 0.47). One study in this analysis was an RCT that compared the effects of specialized JSO treatment with treatment as usual (Borduin et al. 1990) and one was an RCT that compared two specialized JSO treatments (Borduin et al. 2009). One used nonrandom assignment, but reported baseline measures of equivalence between treatment and comparison groups (Worling and Curwen 2000), and one used nonrandom assignment and reported baseline measures for the treatment group only (Cooper and Schmidt 2000).

As summarized in Table 1, there is relatively little overlap between the studies included in these previous meta-analyses. Only three studies appeared in at least half of them (Borduin et al. 1990; Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000). Additionally, despite the accumulation of research over time, the inclusion criteria of the more recent meta-analyses do not appear to be more stringent than the inclusion criteria for the earlier meta-analyses. The only exception is Schmucker and Lösel’s (2015) updated meta-analysis, which improved upon their 2005 meta-analysis but only included studies through 2010.

The present study

The present study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of research examining the effects of specialized treatment for JSOs on sexual and general recidivism. Because the majority of previous meta-analyses have included some studies for which the treatment–control comparison was not well controlled, the extent to which those studies may have introduced bias into their findings is uncertain. The meta-analysis reported here, therefore, focused exclusively on studies that met specified research design criteria designed to select the methodologically strongest studies available (described below). Moreover, we wanted to identify and include any such studies that had been reported during the 5 years that have elapsed since the date of the most recent studies included in the most recent meta-analysis on this topic (Schmucker and Lösel 2015).

Inclusion criteria

To be included in this systematic review and meta-analysis, studies had to assess the effects of psychosocial therapeutically oriented treatment focused on sexual offending and provided exclusively to JSOs. Eligible treatment programs could be implemented individually with JSOs or in groups composed entirely of JSOs, but could not be implemented in mixed groups that included juveniles who have not committed sexual offenses. The key distinction made here between specialized treatment and other forms of treatment in which JSOs may participate is that the former is oriented in some way specifically to JSOs whereas the latter do not make any such distinction and are provided to both JSOs and general offenders.

These inclusion criteria thus excluded studies that examined the effects of exclusively pharmaceutical or medical treatments (although no studies were excluded solely for this reason) or interventions that did not have a primary therapeutic orientation (e.g., incarceration, probation, deterrent programs). They also excluded studies in which members of the comparison group all received the same distinct focal treatment. Such comparative treatment effectiveness studies do not assess the value of specialized sex offender treatment relative to juvenile justice treatment as usual or relative to no treatment conditions.

In addition, eligible studies had to report outcomes for juveniles under the age of 21 who have committed acts that constitute chargeable sexual offenses and be implemented with samples of juveniles resident in the USA or a predominately English-speaking country. The latter requirement was intended (1) to restrict the sample of studies to those set in juvenile justice systems with comparable social contexts around juvenile justice and (2) to limit the definitions of juvenile sex offenses to those substantially similar to definitions in the USA. While juvenile justice in Canada and Australia (the only other countries represented in the eligible studies) exhibits important similarities and differences compared to the USA (Winterdyk 2002), all have distinct systems for processing juveniles separately from adults with goals that include positive youth development while also holding youth accountable for their misbehavior.

A further requirement was that studies use random assignment of juveniles to conditions, match them on one or more recognized risk factors for recidivism (e.g., offense history, rape myth acceptance, attitudes toward violence, etc.), or report baseline measures of group differences on such risk factors. Finally, studies were only eligible if they reported quantitative outcome data for at least one delinquency measure and were published or reported in 1950 or later, but conducted no earlier than 1945.

Search strategy

We took several steps to identify eligible studies for this meta-analysis. First, we searched a large parent meta-analysis database of studies evaluating the effects of psychosocial, therapeutically oriented interventions or therapies among juveniles who have committed a chargeable offense (sexual or nonsexual in nature). This parent database contains abstracts from over 5000 studies reported or published since the 1950s. It was constructed by the second author in the mid-1980s and, as a result of periodic updates, is current through 2014 (see Lipsey 1992; Lipsey et al. 2010 for a more detailed description of the database).

To identify eligible studies reported or published between January 2014 and December 2015, we conducted an updated search. This involved searching 61 electronic databases, including ProQuest Criminal Justice Database, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, ProQuest Research Library, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts, using the key terms “sex” AND (“adolescent” OR “juvenile") AND (“offense” or “offender”) AND (“treatment” OR “intervention"). Additionally, in an effort to identify eligible studies in the gray literature, we searched Google Scholar, annual conference proceedings of the American Society of Criminology, and the webpages of authors of eligible or nearly eligible studies. We also searched the reference lists of all eligible and nearly eligible studies and of the previous meta-analyses of research evaluating the effects of JSO interventions (see Table 1 for a summary of previous meta-analyses searched).

Data coding and calculation of effect sizes

Each eligible study was independently coded by two members of the research team and disagreements were resolved via consensus. Data were coded on a wide range of variables that included bibliographic information, country where implemented, research design (random assignment, matching, or baseline measures), primary treatment modality for the treatment group, what the comparison group received (treatment as usual, wait-list control), sample sizes, participant characteristics (sex, race, age), and months over which the recidivism outcomes were counted.

The outcome variables coded were sexual and general recidivism, defined as police contact/arrest or court contact for sexual offenses or any offenses, respectively. All the eligible studies reported binary measures of recidivism (recidivated or not within the period assessed). We thus report effect sizes as odds ratios defined as the odds of recidivating in the treatment group divided by the odds of recidivating in the comparison group. Odds ratios greater than 1.00 therefore indicate that the treatment group recidivated more than the comparison group, and values less than 1.00 indicate that the treatment group recidivated less than the comparison group. A zero-cell count was reported for two outcomes in the meta-analytic sample. Following procedures recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, we added 0.5 to each of the four cells used to calculate the pertinent odds ratios (Higgins and Green 2011).

We employed an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach whenever possible and defined treatment groups as consisting of individuals assigned to receive treatment regardless of how much treatment they actually received. The benefits of the ITT approach are that it reflects practical clinical scenarios in which individuals receive varying levels of treatment and helps maintain whatever initial treatment–control group equivalence was created by the research design and statistical controls used for that purpose (Gupta 2011). Three studies in our meta-analysis reported recidivism data separately for those who completed treatment and those who refused or dropped out. In these cases, we combined recidivism data from the completers and noncompleters within the respective treatment and comparison groups and used those overall recidivism rates to generate ITT effect size estimates.

Analytic strategy

We conducted two separate analyses: one assessing the effects of specialized treatment on juveniles’ sexual recidivism and one assessing the effects of specialized treatment on juveniles’ general recidivism. For each analysis, we report both fixed effects and random effects models with inverse variance weighting, but recognize that the small number of studies does not allow the between-studies random effects variance component to be reliably estimated. Nonetheless, the fixed effects and random effects models produced substantively similar findings and, in the interest of parsimony, we only present forest plots for the fixed effects estimates.

To avoid dependencies in a given analysis, each individual study contributed no more than one effect size to each of these meta-analyses. Most of the studies reported either police or court contact as a measure of sexual or general recidivism. In the one case where both were reported, we calculated the effect size as the mean of the odds ratios for both outcomes. All but one study in the sample reported outcomes for a single post-treatment follow-up wave. For the one study that reported outcomes for two waves of measurement, we calculated recidivism effect sizes only for the first of those to maintain comparability across the studies.

Results

Study characteristics

Results from the search process are outlined in the PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1. The final sample for the meta-analysis consisted of eight studies described in 12 reports. The primary reports for each study were journal articles (k = 7) and an unpublished thesis (k = 1). Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Four studies were conducted in the USA, two were conducted in Australia, and two were conducted in Canada.

Sample sizes ranged from 16 to 190. Treatment samples were largely male (90 to 100%). Where reported (k = 4), the treatment samples were mostly White (53 to 67% of the participants). The mean age of the treatment groups, where reported (k = 4), ranged from 13.5 to 15.4. Three studies included some juveniles below the age of 13 (Byrne 1999; Gillis and Gass 2010; Laing et al. 2014). Treatment of preteen youth who commit sexual offenses often differs from treatment of older juveniles by including some child behavior management component for parents (Chaffin 2008). However, we saw no evidence of this type of treatment in our sample.

One study in the sample was a randomized control trial (RCT). The remaining study samples were either matched on some set of background characteristics that included a risk factor for recidivism (k = 2) or researchers reported baseline measures of at least one risk factor for recidivism that could be used to assess equivalence between the treatment and comparison groups (k = 5). Among those five studies reporting baseline equivalence measures, two reported that differences were not statistically significant between groups (Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000). One (Byrne 1999) found no significant differences for total number of prior offenses and prior sexual offenses, but did find a significant difference in the number of prior sexual charges that favored the comparison group. Another study (Daly et al. 2013) did not test for statistical significance but reported data for baseline pre-index sexual offending for treatment and control groups that was sufficient to calculate an effect size that was sizable, but not statistically significant (OR = .52, 95% CI 0.23, 1.17). The remaining study (Guarino-Ghezzi and Kimball 1998) found no significant baseline differences on relevant variables for the initial sample, but did not assess those differences for the smaller subsample for which outcome data were reported. More detail about group equivalence measures for each of the eligible studies can be found in Table 2, and the results of tests of the sensitivity of our findings to inclusion of these studies are reported later.

The primary treatment modality in seven of the eight studies was some variant of counseling. Group counseling was the treatment in three studies, family counseling in two, individual counseling in one, and mixed counseling (a combination of group, family, and individual counseling) in one. The treatment modality in the remaining study was a skill-building program, specifically an adventure-based behavior management program. All programs for the treatment groups were specifically tailored to JSOs. Participants in the comparison groups either received juvenile justice treatment as usual (k = 7) or were in a wait-list control group (k = 1) for which it was unclear what services if any they received. Three of the treatments were provided in residential settings and the remaining five were in community settings.

Table 3 provides a more detailed description of the services received by treatment and comparison groups. Note that many of the treatments (n = 5) focused on fostering victim empathy or awareness and accountability, and taking responsibility for sexual offending. These are popular treatment components in programs implemented with adult sex offenders but are not significant predictors of sexual recidivism (Hanson and Morton-Bourgon 2005; Letourneau and Borduin 2008; McGrath et al. 2010). In addition, though none of the treatment programs was described explicitly as fully formed cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), a number of CBT techniques appeared in the descriptions (e.g., relapse prevention, cognitive restructuring, and attention to dysfunctional thinking patterns and attitudes). One of the studies explicitly implemented Multisystemic Therapy (MST) (Borduin et al. 1990).

There was one noteworthy study that we deemed ineligible because it failed to contrast a specialized treatment program with an eligible comparison group. Borduin et al. (2009) used an RCT research design and demonstrated a favorable treatment effect on general recidivism. Although this study was well designed, we excluded it under our eligibility criteria because the juveniles in the comparison group received a distinct singular treatment service; that is, this study compared two distinct focal treatments (specialized MST received by the treatment group and specialized CBT by the comparison group). Although comparative treatment effectiveness studies provide valuable information about which specific treatments are more effective than others, the intent of this meta-analysis is to determine the effects of specialized sex offender treatment in comparison to the services juveniles would presumably receive if they were treated as general offenders rather than sex offenders (e.g., treatment as usual identified as such or a mix of the kinds of services typically available to juveniles in juvenile justice contexts).

Estimated treatment effects

Seven studies reported sexual recidivism outcomes and six reported general recidivism outcomes (see Table 4). Where reported (k = 7), the total number of months over which recidivism was counted ranged from 12 to 75 with the post-treatment months within those periods ranging from 12 to 58. The discrepancy in the upper bound of these two ranges is due to the fact that two studies reported recidivism over a period that began before treatment completion.

Sexual recidivism

The sexual recidivism rates ranged from 0 to 12.7% for treatment groups and from 3.7 to 75% for comparison groups (although removing the 75% outlier reduces the upper bound to 13%). Odds ratio effect sizes ranged from 0.05 to 1.27, with effect sizes from four studies indicating a favorable outcome for treatment (OR < 1.00), two studies indicating virtually no difference between the treatment and comparison groups (OR = 0.97 and 1.00), and one study indicating a favorable outcome for the comparison group (OR > 1.00). As illustrated by the forest plot in Fig. 2, the 95% confidence interval for six of the seven individual effect sizes contained the null value (OR = 1.00), indicating that only one of these effect sizes was statistically significant (Borduin et al. 1990).

The inverse-variance weighted fixed effects mean effect size for sexual recidivism across all seven of these studies was OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.40, 1.36. The inclusion of the null value in the confidence interval indicates a nonsignificant average treatment effect. Thus, on average, participants receiving specialized treatment did not exhibit significantly different odds of sexual recidivism than those in the comparison groups, although the direction of the effect estimate was in a favorable direction. An important limitation of this analysis is the small number of studies and the relatively small participant sample sizes in each. These conditions provide very little statistical power for detecting effects at either the individual study level or for the meta-analytic mean effect size.

In addition, though descriptively the odds ratios show variability, the heterogeneity across the individual study effect sizes was not statistically significant (Q = 7.14 (df = 6, p = 0.31)). Findings from an inverse-weighted random effects model were nearly identical to those from the fixed effects model (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.40, 1.38), with nonsignificant heterogeneity across individual study effect sizes (Q = 7.14 (df = 6, p = 0.31)).

Because there were so few studies and such little heterogeneity among the effect sizes, moderator analysis was not appropriate. However, due to the diverse nature of the included studies in terms of treatment approach, research design, and baseline equivalence, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses in which we ran fixed effects models removing the effect of each individual study from the analysis in sequential steps. As summarized in Table 5, the findings did not change appreciably with the removal of any individual study. The mean effect sizes for each sensitivity analysis model remained nonsignificant. However, the removal of a few specific studies did create some (nonsignificant) substantive changes of note. Removing Borduin et al. (1990) increased the mean effect size from 0.74 to a less favorable 0.87. This is not necessarily surprising, as Borduin et al. was the only study to demonstrate a significant treatment effect, albeit one based on a small sample (n = 16) and an estimate of control group recidivism that was an extreme outlier (see Table 4). Removing Laing et al. (2014) and Worling and Curwen (2000) each independently decreased the mean effect size from 0.74 to a more favorable 0.64. Laing et al. was the only study to demonstrate a (nonsignificant) favorable effect for the comparison group, and the effect size for Worling and Curwen was very close to the null value (i.e., 0.97).

General recidivism

Six studies reported a measure of general recidivism; that is, an aggregate measure of reoffending for any offense that was not restricted to sex-related offenses but would include them if they occurred. As summarized in Table 4, general recidivism rates were higher than sexual recidivism rates, ranging from 18.9 to 53.8% for treatment groups and from 16.5 to 75% for comparison groups. Effect sizes ranged from 0.39 to 1.58, with those from five studies indicating a favorable outcome for the treatment group and the effect size from one study indicating a favorable outcome for the comparison group. Assessed individually, however, only two of these effects were statistically significant (see Fig. 3).

Nonetheless, the fixed effects weighted mean effect size across these six studies was statistically significant (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.42, 0.81). That is, the mean odds that participants in specialized treatment recidivated for any offense were only 58% of those for the comparison groups. As with sexual recidivism, tests of heterogeneity did not indicate that the apparent variation of the effect sizes across these studies was statistically significant (Q = 7.64 (df = 5, p = 0.18)). Findings from an inverse-weighted random effects model were similar to those from the fixed effects model (OR = 0.59, 95% CI (0.39, 0.89)), with nonsignificant heterogeneity across individual study effect sizes (Q = 7.64 (df = 5, p = 0.18)).

Again, we should note that the small number of studies and their relatively small sample sizes did not provide a great deal of statistical power for these analyses. Because of that small number of studies and the minimal, nonsignificant heterogeneity of the effect sizes, we did not attempt any moderator analysis to explore potential sources of variation among the effect sizes. However, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses for the general recidivism outcomes in which we ran fixed effects models removing the effect of each individual study from the analysis sequentially. As summarized in Table 6, findings remained significant in each of the sensitivity analysis models. We found the greatest change in mean effect size magnitude when dropping Lab et al. (1993), which reduced the mean effect size from 0.58 to a more favorable 0.49. This is not surprising, as Lab et al. was the only study that demonstrated a (nonsignificant) favorable effect for the comparison group. Dropping each of the remaining studies in turn increased the mean effect size from 0.58 to less favorable values that ranged between 0.60 and 0.63.

Discussion

Perhaps the most important finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis is how few studies meeting our inclusion criteria were located despite our vigorous search. Most juvenile justice systems in the USA make use of specialized programs for offenders adjudicated for sex-related offenses. Given the prevalence of such programs, it is somewhat stunning to realize that over the broad timeframe covered in our search (1950–2015) only eight studies that met our inclusion criteria could be found. The intent of the methodological parts of those inclusion criteria was to focus on studies using relatively rigorous research designs for estimating causal treatment effects. However, only one RCT study was found and only two of the eight studies attempted to match youth in the treatment and comparison groups on relevant baseline variables. The remaining five studies were neither randomized nor matched and only reported measures of baseline equivalence between treatment and control groups. While baseline differences were not statistically significant for three of these five studies (Daly et al. 2013; Lab et al. 1993; Worling and Curwen 2000), their modest sample sizes did not provide a high level of statistical power for those tests. One of the remaining two studies reported a significant baseline difference on a key risk variable (Byrne 1999), and the other reported insufficient data for a statistical assessment of group equivalence (Guarino-Ghezzi and Kimball 1998).

With the benefit of a decade or more since the publication of most of the previous meta-analyses, we expected to be able to limit our sample to studies with higher quality designs while still having an adequate number for differentiated analysis. Previous meta-analyses, perhaps to have enough studies to support more than a minimal analysis, have included studies with research designs that fell below the criteria used here (e.g., studies comparing JSOs who completed treatment with those who dropped out, comparing JSOs to nonsexually offending youth, comparing JSOs who commit serious acts with those committing less serious acts). This difference may explain why most previous meta-analyses reported statistically significant effects on JSOs’ sexual recidivism, whereas our analysis did not.

The findings of this meta-analysis, however, must be interpreted within the confines of its limitations. Aside from the shortage of RCTs and especially well-controlled quasi-experiments, the small number of studies and their modest sample sizes limited the statistical power of our meta-analysis to detect overall mean effects of moderate magnitude. This, along with the small amount of heterogeneity among the effect sizes, additionally precluded exploration of potential moderators of treatment effects. Moreover, only four studies in the complete sample and three of those measuring sexual recidivism were published in 2000 or later. Thus, it is questionable whether the specialized treatment of JSOs in any of these studies met contemporary treatment standards (see Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers 2017).

If sufficient rigorous research on contemporary treatment of JSOs accumulates, future meta-analyses should examine the potential moderating effects of factors such as offender characteristics, specific treatment components, and community vs. residential treatment settings. It is also worth noting that the studies in our sample used participant samples that were composed almost exclusively of males, thus offering no insight into treatment effects on the rather different pattern of sex-related offenses for females.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings highlight some important questions about appropriate treatment of juveniles charged with sex-related offenses that have been raised by the researchers cited in the introduction to this paper. Though the studies in our sample focused on juveniles identified as sex offenders, the recidivism rates for sex offenses were low. This should not be surprising considering that sexual recidivism among both JSOs and adult sex offenders has generally been found to be relatively low (Caldwell 2016; Helmus et al. 2012). Moreover, the low rate of sexual recidivism in our sample cannot be explained by a reduction in delinquent behavior overall (recidivism rates for general offenses were much higher). This pattern is similar to that found in Caldwell’s (2016) meta-analysis of recidivism rates for juveniles adjudicated for sex offenses. There is a wide range of sexual recidivism patterns among JSOs (Worling and Langstrom 2006), and the fact that only a small proportion go on to commit further sexual offenses suggests that few of them are the kinds of specialist sex offenders who would be most likely to benefit from specialized treatment. If most of the JSO-labeled youth who receive specialized treatment have low risk for further sex offenses to begin with, it is not surprising to find little or no overall effects on such offenses.

While the mean odds ratio for the sexual recidivism of JSOs found in this meta-analysis is in a direction favorable to specialized treatment (mean OR = 0.74), albeit not statistically significant, it is notable that the effect of that treatment was even greater on general recidivism (mean OR = 0.58). These especially positive effects on general recidivism are consistent with the presumption that most JSO-labeled youth are general offenders rather than specialist sex offenders. However, it is not readily apparent why specialized sex offender treatment should have positive effects on the recidivism of general offenders. This might be explained by the nature of the treatment modalities used in our sample of studies, most of which were variants of individual, group, or family counseling. These are common treatment approaches for general offenders as well, and it is plausible that the content of the various counseling sessions ranged beyond issues specifically associated with the initial sex offenses.

With these considerations in mind, it would be especially informative if future research on specialized sex offender treatment would distinguish likely specialist offenders (those at relatively high risk of sexual recidivism) in the treatment sample from generalist offenders (youth who happened to commit a sexual offense but exhibit low risk of sexual recidivism). Unfortunately for this purpose, current sexual risk assessment tools do not seem to perform especially well for predicting subsequent sexual offending (Dwyer and Letourneau 2011; Viljoen et al. 2012) nor for distinguishing subtypes among JSOs (Rajlic and Gretton 2010).

This highlights another important direction for future research—development of more accurate means to distinguish juvenile offenders at risk of sexual recidivism from more general offenders who may commit a sex-related offense but are not likely to commit another. As Letourneau and Miner (2005) have argued, “well-designed research studies on juvenile sex offenders and the integration of those studies with findings from general delinquency and developmental literatures will lead to the development of more appropriate and effective legal and clinical interventions for these youths” (p. 307). The results of our meta-analysis indicate that the key elements of such well-designed studies should include distinguishing juveniles at high vs. low risk of sexual recidivism among JSO-labeled youth and using rigorous methods to assess the effects of well-formulated specialized treatment for those at high risk. Without such studies, little guidance can be provided about effective evidence-based practice for treating juvenile sex offenders to the many juvenile justice systems that must deal with those youth.

References

* Indicates study included in meta-analysis

Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers. (2017). Practice guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and intervention with adolescents who have engaged in sexually abusive behavior. Beaverton, OR; Author.

Barlow, K. N. (1996). Recidivism rates of level six residential programs for youthful male sex offenders: 1995–1996. Unpublished master’s thesis. Utah State University.

Becker, J. V., & Hicks, S. J. (2003). Juvenile sexual offenders: characteristics, interventions, and policy issues. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 989, 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07321.x.

Borduin, C. M., & Schaeffer, C. M. (2001). Multisystemic treatment of juvenile sexual offenders: a progress report. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 13, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v13n03_03.

*Borduin, C. M., Henggeler, S. W., Blake, D. M., & Stein, R. J. (1990). Multisystemic treatment of adolescent sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34, 105–113. Related Report: Borduin, C. M., Mann, B. J., Cone, L. T., Henggeler, S. W., Fucci, B. R., Blaske, D. M., & Williams, R. A. (1995). Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders: long-term prevention of criminality and violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 569-578.

Borduin, C. M., Schaeffer, C. M., & Heiblum, N. (2009). A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013035. Related Report: Borduin, C. M., & Dopp, A. R. (2015). Economic impact of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 687-696. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000113. Related Report: Borduin, C. M. & Schaeffer, C. M. (2001). Multisystemic treatment of juvenile offenders: a progress report. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 13, 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v13n03_03.

Brannon, J. M., & Troyer, R. (1991). Peer group counseling: a normalized residential alternative to the specialized treatment of adolescent sex offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 35, 225–234.

*Byrne, S. M. (1999). Treatment efficacy of a juvenile sexual offender treatment program. (Unpublished masters thesis). Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada.

Caldwell, M. F. (2016). Quantifying the decline in juvenile sexual recidivism rates. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22, 414–426. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000094.

Chaffin, M. (2008). Our minds are made up—don’t confuse us with the facts: commentary on policies concerning children with sexual behavior problems and juvenile sex offenders. Child Maltreatment, 13, 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559508314510.

Chaffin, M., & Bonner, B. (1998). Don’t shoot, we’re your children: have we gone too far in our treatment of adolescent sexual abusers and children with sexual behavior problems? Child Maltreatment, 3, 314–316.

Cooper, H. M., & Schmidt, F. (2000). Long-term follow-up of a community-based treatment program for adolescent sex offenders. Unpublished manuscript.

*Daly, K., Bouhours, B., Broadhurst, R., & Loh, N. (2013). Youth sex offending, recidivism and restorative justice: comparing court and conference cases. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 46, 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865812470383. Related Report: Daly, K. (2006). Restorative justice and sexual assault: an archival study of court and conference cases. British Journal of Criminology, 46, 334-356. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azi071.

Dwyer, R. G., & Letourneau, E. J. (2011). Juveniles who sexually offend: recommending a treatment program and level of care. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.03.007.

*Gillis, H. L., & Gass, M. A. (2010). Treating juveniles in a sex offender program using adventure-based programming: a matched group design. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19, 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538710903485583.

*Guarino-Ghezzi, S., & Kimball, L. M. (1998). Juvenile sex offenders in treatment. Corrections Management Quarterly, 2, 45–54.

Gupta, S. K. (2011). Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2, 109–112. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.83221.

Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: a meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 1154–11163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154.

Hanson, R. K., Gordon, A., Harris, A. J. R., Marques, J. K., Murphy, W., Quinsey, V. L., & Seto, M. C. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14, 169–194.

Hanson, R. K., Bourgon, G., Helmus, L., & Hodgson, S. (2009). The principals of effective correctional treatment also apply to sexual offenders: a meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 865–891.

Harris, A. J., & Socia, K. M. (2016). What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” label on public opinions and beliefs. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 28, 660–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214564391.

Helmus, L., Hanson, R. K., Thornton, D., Babchishin, K. M., & Harris, A. (2012). Absolute recidivism rates predicted by STATIC-99R and STATIC-2002R sex offender risk assessment tools vary across samples: a meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39, 1148–1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812443648.

Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (eds) (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Hurley, S. (2003). Unpublished raw data.

Jeffords, C. (2003). Unpublished raw data.

Kahn, T. J., & Chambers, H. J. (1991). Assessing reoffense risk with juvenile sex offenders. Child Welfare, 70, 331–345.

Kim, B., Benekos, P. J., & Merlo, A. V. (2016). Sex offender recidivism revisited: review of recent meta-analyses on the effects of sex offender treatment. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 17, 105–117.

*Lab, S. P., Shields, G., & Schondel, C. (1993). Research note: an evaluation of juvenile sex offender treatment. Crime & Delinquency, 39, 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128793039004008.

*Laing, L., Tolliday, D., Kelk, N., & Law, B. (2014). Recidivism following community based treatment for non-adjudicated young people with sexually abusive behaviors. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 6, 38–47.

Letourneau, E. J., & Borduin, C. M. (2008). The effective treatment of juveniles who sexually offend: an ethical imperative. Ethics & Behavior, 18, 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420802066940.

Letourneau, E. J., & Miner, M. H. (2005). Juvenile sex offenders: a case against the legal and clinical status quo. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 17, 293–312.

Lipsey, M. W. (1992). Juvenile delinquency treatment: A meta-analytic inquiry into the variability of effects. In T. D. Cook, H. Cooper, D. S. Cordray, H. Hartmann, L. V. Hedges, R. J. Light, T. A. Louis, & F. Mosteller (Eds.), Meta-analysis for explanation: A casebook (pp. 83–127). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lipsey, M. W., Howell, J. C., Kelly, M. R., Chapman, G., & Carver, D. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of juvenile justice programs: A new perspective on evidence-based practice. Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 117–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-004-6466-7.

McGrath, R. J., Cumming, G. F., Burchard, B. L., Zeoli, S., & Ellerby, L. (2010). Current practices and emerging trends in sexual abuser management: the Safer Society 2009 North American Survey. Brandon: The Safer Society Press.

McTavish, T. H. (1996). Performance audit of the W.J. Maxey Training School. Unpublished report.

National Adolescent Perpetrator Network. (1993). Revised report from the National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 44, 1–115.

Oudekerk, B. A., & Morgan, R. E. (2016). Co-offending among adolescents in violent victimizations, 2004–13. Washington DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice.

Pullman, L., & Seto, M. C. (2012). Assessment and treatment of adolescent sexual offenders: implications of recent research on generalist versus specialist explanations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 203–209.

Rajlic, G., & Gretton, H. M. (2010). An examination of two sexual recidivism risk measures in adolescent offenders: the moderating effect of offender type. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 1066–1085.

Rasmussen, L. A. (1995). Factors related to recidivism among juvenile sex offenders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Utah.

Reitzel, L. R., & Carbonell, J. L. (2006). The effectiveness of sexual offender treatment for juveniles as measured by recidivism: a meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse, 18, 401–421.

Schmucker, M., & Lösel, F. (2015). The effects of sexual offender treatment on recidivism: an international meta-analysis of sound quality evaluations. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11, 597–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-015-9241-z.

Seabloom, W., Seabloom, M. E., Seabloom, E., Barron, R., & Hendrickson, S. (2003). A 14- to 24-year longitudinal study of a comprehensive sexual health model treatment program for adolescent sex offenders: predictors of successful completion and subsequent criminal recidivism. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47, 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X03253849.

Seto, M. C., & Lalumiere, M. L. (2010). What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 526–575.

Viljoen, J. L., Mordell, S., & Beneteau, J. L. (2012). Prediction of adolescent sexual reoffending: a meta-analysis of the J-SOAP-II, ERASOR, J-SORRAT-II, and Static-99. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093938.

Waite, D., Keller, A., McGarvey, E. L., Wieckowski, E., Pinkerton, R., & Brown, G. L. (2005). Juvenile sex offender re-arrest rates for sexual, violent nonsexual, and property crimes: a 10-year follow-up. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 17, 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11194-005-5061-4.

Walker, D. F., McGovern, S. K., Poey, E. L., & Otis, K. E. (2004). Treatment effectiveness for male adolescent sexual offenders: a meta-analysis and review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 13, 281–293.

Wieckowski, E., Waite, D., Pinkerton, R., McGarvey, E., & Brown, G. L. (2003). Sex offender treatment in a juvenile correctional setting: program description and nine-year outcome study. Unpublished presentation.

Winokur, M. A., Rozen, D., Batchelder, K., & Valentine, D. (2006). Juvenile sexual offender treatment: a systematic review of evidence-based research. Fort Collins: Social Work Research Center, Colorado State University.

Winterdyk, J. (2002). Juvenile justice systems: international perspectives (2nd ed.). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Wolk, N. L. (2005). Predictors associated with recidivism among juvenile sexual offenders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Houston.

*Worling, J. R., & Curwen, T. (2000). Adolescent sexual offender recidivism: success of specialized treatment and implications for risk prediction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 965–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145.2134(00)00147-2. Related Report: Worling, J. R. (1998). Adolescent sexual offender treatment at the SAFE-T program. In W. L. Marshall, Y. M. Fernandez, S. M. Hudson, & T. Ward (Eds.), Sourcebook of treatment programs for sexual offenders (pp. 353-365). New York: Plenum Press. Related Report: Worling, J. R., Littlejohn, A., & Bookalam, D. (2010). 20-year prospective follow-up study of specialized treatment for adolescents who offend sexually. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 28, 46-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.912.

Worling, J. R., & Langstrom, N. (2006). Risk of sexual recidivism in adolescents who offend sexually: correlates and assessment. In H. E. Barbaree & W. L. Marshall (Eds.), The juvenile sex offender (2nd ed., pp. 219–247). New York: Guilford Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gabrielle Chapman and Jill Robinson for their valuable input as well as Jan Morrison for her support throughout the project.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant No. 2010-JF-FX-0607 awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not report the results of any research conducted by the authors that involves human participants or animals.

Informed consent

This article does not involve data obtained by the authors from human participants.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kettrey, H.H., Lipsey, M.W. The effects of specialized treatment on the recidivism of juvenile sex offenders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Exp Criminol 14, 361–387 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9329-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9329-3