Abstract

Objectives

Sound evaluations of sexual offender treatment are essential for an evidence-based crime policy. However, previous reviews substantially varied in their mean effects and were often based on methodologically weak primary studies. Therefore, the present study contains an update of our meta-analysis in the first issue of this journal (Lösel and Schmucker Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 117–146, 2005). It includes more recent primary research and is restricted to comparisons with equivalent treatment and control groups and official measures of recidivism as outcome criteria.

Methods

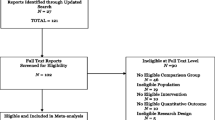

Applying a detailed search procedure which yielded more than 3000 published and unpublished documents, we identified 29 eligible comparisons containing a total of 4,939 treated and 5,448 untreated sexual offenders. The study effects were integrated using a random effects model and further analyzed with regard to treatment, offender, and methodological characteristics to identify moderator variables.

Results

All eligible comparisons evaluated psychosocial treatment (mainly cognitive behavioral programs). None of the comparisons evaluating organic treatments fulfilled the eligibility criteria. The mean effect size for sexual recidivism was smaller than in our previous meta-analysis but still statistically significant (OR = 1.41, p < .01). This equates to a difference in recidivism of 3.6 percentage points (10.1 % in treated vs. 13.7 % in untreated offenders) and a relative reduction in recidivism of 26.3 %. The significant overall effect was robust against outliers, but contained much heterogeneity. Methodological quality did not significantly influence effect sizes, but there were only a few randomized designs present. Cognitive-behavioral and multi-systemic treatment as well as studies with small samples, medium- to high-risk offenders, more individualized treatment, and good descriptive validity revealed better effects. In contrast to treatment in the community, treatment in prisons did not reveal a significant mean effect, but there were some prison studies with rather positive outcomes.

Conclusions

Although our findings are promising, the evidence basis for sex offender treatment is not yet satisfactory. More randomized trials and high-quality quasi-experiments are needed, particularly outside North America. In addition, there is a clear need of more differentiated process and outcome evaluations that address the questions of what works with whom, in what contexts, under what conditions, with regard to what outcomes, and also why.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual offending is a topic of particularly high concern in the general public, mass media and in crime policy making. Accordingly, many governments of industrialized countries have implemented not only more punitive measures but have also invested in treatment of sexual offenders to reduce recidivism. However, there is much controversy about the effectiveness of sex offender treatment, in particular with regard to methodological issues (e.g., Marshall and Marshall 2010; Rice and Harris 2003; Seto et al. 2008). A general conclusion and consensus on ‘what works’ in this field is complicated by various issues:

-

1.

Sexual offending is a very heterogeneous category that contains, for example, various forms of child molesting, rape, exhibitionism, distribution and consumption of child pornography on the internet and other forms.

-

2.

There are very different types of sexual offenders such as those with (or without) a deviant sexual preference (paraphilia), an antisocial personality, an opportunistic orientation, neuropsychological deficits, and so forth (Robertiello and Terry 2007).

-

3.

Although there is much research on risk factors for reoffending and structured assessment instruments (e.g., Hanson and Morton-Bourgon 2009), the knowledge about the origins and causal mechanisms is less clear (e.g., Mann et al. 2010; Ward et al. 2005).

-

4.

Treatment approaches are heterogeneous, ranging from psychosocial interventions such as cognitive–behavioral programs and relapse prevention or psychodynamic therapy to organic interventions such as hormonal treatment by medication or surgical castration, and some of these categories embrace rather different therapeutic measures in themselves (e.g., Marshall et al. 1998; McGrath et al. 2010).

-

5.

Sound treatment evaluation is difficult because in various jurisdictions serious sexual offenders cannot simply be left untreated in control groups, the base rate of sexual recidivism is relatively low, and with regard to sexual reoffending longer follow-up periods are required compared to other fields of correctional intervention.

For such reasons, controlled evaluations of programs for sexual offenders are less frequent than in general or violent offender treatment, particularly outside North America (Lipsey and Cullen 2007; Lösel 2012). However, over the last 20 years, the number of studies has increased and more than a dozen systematic reviews or meta-analyses have been carried out (for overviews, see Corabian et al. 2011; Lösel and Schmucker 2014). Although there is overlap between most of these syntheses, they vary substantially with regard to the included primary studies, coding schemes, methods of effect size calculation and integration as well as the investigation of outcome moderators. Some meta-analyses concentrated on psychotherapeutic/psychosocial interventions only (e.g., Hanson et al. 2002), whereas others also included hormonal medication and surgical castration (Lösel and Schmucker 2005). Within the category of psychotherapeutic/psychosocial interventions, the specific treatment programs not only vary considerably but also share similarities. For example, the contents of cognitive–behavioral treatment (CBT), such as reducing deviant sexual attitudes, improving self-control, enhancing social skills, promoting perspective taking, or coping with stressors, overlap with those of relapse prevention programs that focus on the control of risk situations. Multi-systemic therapy for young sexual offenders and social therapy/therapeutic communities make particular use of the social context of the clients, but also incorporate elements from CBT, attachment and psychodynamic approaches. Hormonal treatment is primarily used for offenders who are mainly motivated by sexual drive and not by dominance or other motivations, but medication is often accompanied by psychosocial interventions. The available research syntheses also vary with regard to the countries of origin or language (e.g., most concentrated on reports in English), outcome criteria (e.g., reoffending vs. other variables) and, in particular, methodological quality of the studies included.

Given this tremendous diversity of interventions, it is not surprising that the magnitude of treatment effects vary substantially (Lösel and Schmucker 2014), although the two most comprehensive meta-analyses revealed similar results with regard to those types of treatment in which they overlapped (psychosocial interventions; Hanson et al. 2002; Lösel and Schmucker 2005). However, due to the low number of high-quality evaluations, that is, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or good quasi-experiments with equivalent control groups, the results of these reviews should not be seen as a definite answer to ‘what works in sexual offender treatment’ but rather as steps in a development to establish a sound evidence base. A good example for such a process is the review of Hanson et al. (2009) that showed that the Risk–Need–Responsitivity (RNR) model of offender treatment (Andrews and Bonta 2010) can be transferred from general to sexual offender treatment.

Against this background, the present meta-analysis aims to progress further along the pathway towards a sound knowledge base on the effects of sexual offender treatment. Building on and updating our previous meta-analysis (Lösel and Schmucker 2005), we now focus on just methodologically sound studies and reoffending outcomes. This should provide the currently most valid international database on the effects of sexual offender treatment.

Methods

Criteria for inclusion of studies

In order to be eligible for the meta-analysis, primary studies had to have the following characteristics:

-

1.

Study of male sexual offenders. Participants had to have been convicted of a sexual offense or to have committed acts of illegal sexual behavior that would have led to a conviction if officially prosecuted. Studies on female sex offenders were not eligible. From the little that is known about female sex offending, we have to assume that it is not just a blueprint of its male counterpart (e.g., Freeman and Sandler 2008).

-

2.

Evaluation of treatment. No restrictions were made on the kind of intervention applied as long as it aimed to reduce recidivism (i.e., psychosocial as well as organic treatment modes such as hormonal medication by medroxyprogesterone or cyproterone acetate and surgical castration were eligible). However, interventions had to incorporate therapeutic measures; purely deterrent or punishing approaches were not included. Treatment did not have to be specifically tailored for sexual offenders. General offender treatment programs were eligible if the study addressed at least a subgroup of sexual offenders and reported separate results for these in both the treated and control groups.

-

3.

Study design. The study had to report the same recidivism outcome for the treatment group (TG) and a control group (CG) not receiving the program under investigation. Apart from randomized studies, we included comparisons from quasi-experimental designs if there were no serious doubts regarding the equivalence of treatment and control groups. This included studies that used appropriate matching procedures, demonstrated equivalence by comparison of and/or statistical control for relevant variables. Equivalence was also assumed if the criteria of the incidental assignment did not relate to risks of reoffending such as availability of treatment in a certain region/at a certain time. These aspects were reflected in our adaptation of the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale (see Farrington et al. 2002). Level 3 or above had to be reached in order to be eligible. Our adaptation is slightly stricter but a little more differentiated at the upper end of the scale that is of special interest for the synthesis of methodologically sound studies. We used the following categories:

-

Level 1: No control or comparison group.

-

Level 2: Nonequivalent comparison group. Differences on relevant variables effecting recidivism are reported or are to be expected (e.g., treatment dropouts, subjects who refuse treatment).

-

Level 3: Incidental assignment but equivalent control group. No serious doubts that assignment resulted in equivalent groups, or sound statistical control of potential differences.

-

Level 4: Matching procedures. Systematic strategy to attain equivalence of the control group (e.g., theoretically sound matching or propensity score techniques).

-

Level 5: Random assignment of treated and untreated subjects. This level also required absence of selective attrition (in the case of selective attrition studies were downgraded or excluded depending on its severity).

Control groups could consist of untreated offenders or offenders receiving “treatment as usual” or another kind of treatment that differed from the evaluated program in content, intensity and specificity. Waiting-list control groups were included if the design allowed testing of a program effect (see outcome measures).

-

-

4.

Measure of recidivism as outcome. An indication of officially registered new offenses had to be included as a dependent variable. Although recidivism is not a very sensitive indicator of treatment effects (e.g., Barbaree 1997), it is politically and practically most relevant. We followed a broad definition of recidivism (sexual as well as non-sexual offenses). Studies could use criteria such as arrest, charge, conviction or incarceration as long as these definitions drew on officially registered recidivism. In contrast, primary studies focusing exclusively on changes in measures of personality or hormone levels, problem behaviors, or clinical ratings of improvement, and the like were not included. Self-reported offending was also not included because of the severe risk of biased reporting (i.e., denial of offenses).

-

5.

Sample size. Studies had to contain a minimum total sample size of 10 persons with at least 5 offenders in each group. This also excluded case reports.

-

6.

Sufficient data for effect size computation. Studies had to report outcomes in a way permitting the calculation of effect size estimates.

-

7.

Country of origin. No restrictions were made as to where studies were conducted. For economic reasons, we restricted our analysis to studies reported in the English, German, French, Dutch, or Swedish language.

-

8.

Published and unpublished studies. Published as well as unpublished studies were eligible. There were no restrictions regarding the time of publication.

Literature search

The study pool of the present analysis was based on the broad search of 2,039 documents that was reported in Lösel and Schmucker (2005) and updated to cover studies issued prior to 2010. Thus, it concerned at least 6 more years of primary research than the previous meta-analysis.Footnote 1 The coding was also updated for new information where necessary. The search used as many sources as possible to achieve a comprehensive international study pool that included both published and unpublished evaluations (see Schmucker and Lösel 2011). The sources included:

-

Literature databases. We searched multiple databases which tapped different academic subjects: C2-SPECTR, Center for Sex Offender Management (CSOM) documents database, Cochrane Library, Dissertation Abstracts International, ERIC, KrimLit Beta II, MedLine, National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS), PAVNET Online, PsycInfo, Psyndex, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and UK National Health Service National Research Register. While such databases usually cover published reports, some of the databases also refer to unpublished material. Usually, the search combined four different keyword clusters: (1) (abnormal/delinquent) sexual behavior (e.g., sexual, paraphilia, molestation); (2) criminal conduct and population (e.g., criminal, offenders, prison); (3) therapeutic intervention (therapy, treatment, corrections, etc.); and (4) outcome research (e.g., effectiveness, outcomes, recidivism). Search terms were individually adapted to the specific layout and search options the databases allowed for in order to construct manageable, but albeit comprehensive, results.

-

Previous reviews on sexual offender treatment were scanned for included studies.

-

Primary studies were scanned for cross-references (snowball method).

-

Handsearches of pertinent journals. Available journals that are known to publish articles relevant to the topic at hand were searched manually. This search included 16 journals (e.g., Aggression and Violent Behavior; Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health; Journal of Sexual Aggression; Psychology, Crime & Law; Sexual Abuse).

-

Internet search. We also conducted internet searches primarily to find unpublished material. Obviously, the internet cannot be searched in full as it constitutes a rather loosely organized pool of information (Schmucker and Lösel 2011). We visited the internet representations of pertinent institutions (e.g., Departments of Corrections; Ministries of Justice), searched them for information on relevant studies, and followed indications of such research until we could locate the referenced material.

-

Personal inquiries. We personally contacted experts in the field of sexual offender research and asked for their own or other studies that would contribute to our study pool.

Sometimes relevant studies are found incidentally (e.g., in the course of another but related literature search; content alerts of journals and the like). There is the danger that incidentally located studies might bias the study pool depending on the special research interests or typically scanned sources. One might decide to drop such studies from the pool. On the other hand, the aim of a comprehensive review is to include all studies that are available. Our decision was to include such incidentally located studies but to document that they were identified in this way. However, we found that we had either also located such studies by our systematic literature search or on closer inspection they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Whenever titles or abstracts of located material did not clearly suggest that the study was ineligible, we retrieved the full report to determine eligibility.

Units of analysis

Sometimes, references report more than one study. We then referred to the individual studies as the units of analysis. If a study contained multiple dependent (sub-)samples, we used the comparison with the highest internal validity (e.g., if a study compared recidivism rates for the total sample of treated/untreated participants and additionally matched a subsample of these groups on relevant characteristics, we would use the latter comparison). Some primary studies present results for different independent subsamples (e.g., separated according to offense types). In those cases, we used the subsamples as units of analysis when this would improve equivalence between treated and control groups and the report allowed for a differentiated coding of the individual subsamples regarding the coding variables (see below). Following this approach, we extracted 29 comparisons from 27 studies that met our inclusion criteria. In total, the 29 comparisons comprise 4,939 treated and 5,448 untreated offenders.

Study coding

A broad range of variables were coded for descriptive purposes, although not all relevant variables were reported in all reports. The coding of study characteristics followed a detailed coding manual that was extended from our previous meta-analysis (Lösel and Schmucker 2005). For reasons of space, details are not presented here but can be requested from the authors.

Study characteristics

For each study/comparison general features (e.g., type and year of publication, country), characteristics of the sample (e.g., age, offense types, voluntariness of treatment participation, reoffense risk), treatment variables (e.g., basic treatment concept, setting of the treatment, format of the treatment) and methodological features (e.g., Maryland Scale rating, follow-up interval) were coded. Table 1 shows the main basic variables to describe the pool of included comparisons.

To test the objectivity/reliability of the coding, all studies were coded by the first author and a trained member of our research team with experience in the field of offender treatment research. Inter-rater agreement varied across the variables but was overall similar to our previous meta-analysis (Lösel and Schmucker 2005). Especially important categories such as treatment type or quality of design rating reached nearly 100 % and no variable was below 60 %. Relatively low agreement was mostly due to discrepancies regarding the missing status of a variable (e.g., author affiliation was coded as missing more often by the second coder due to a lack of knowledge of affiliation networks specifically for sex offender treatment). In the case of disagreement of the coders, we had a group discussion in the research team to reach consensus.

Effect size computation

Usually, the outcomes are reported in terms of recidivism rates for treated and untreated participants. We thus chose the odds ratio (OR) as the effect size measure (see Fleiss 1994). The following formulas were used for recidivism rates (p) and absolute number of successes and failures in the treated group (TG) and comparison group (CG) respectively:

If any of these frequencies equaled zero, 0.5 was added to each frequency. Some studies reported more sophisticated statistical analyses that controlled for differences between TGs and CGs. In such cases, we used these results instead of the simple recidivism rates. In logistic regression, the coefficients equal the natural log of the OR (LOR), and as an exponent to e this equals the OR (see Fleiss 1994). The result for the treatment variable could thus be transferred directly. In Cox regression, results are reported in the form of a risk ratio, which is similar but not identical to the OR. We used the risk ratio (RR) to estimate a recidivism rate for the CG corrected for the group differences considered in the Cox regression model (p CG = RR × p TG or p CG = RR / p TG, depending on the coding of the treatment variable in the primary study). We then calculated the OR substituting the estimated CG recidivism rate following the above formula. Few studies reported other test statistics that could not be transformed readily into ORs. In these cases, we used standard procedures to calculate Cohen’s d (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001) and then converted these into odds ratios using \( LOR=\frac{\pi }{\sqrt{3}}\times d \) (Hasselblad and Hedges 1995, Formula 4, re-arranged) and OR = e LOR.

Studies often reported multiple outcome variables. Different domains of recidivist behavior (i.e., sexual, violent, or general recidivism) were always analyzed separately. If a study reported different indicators of failure (i.e., charge, arrest, or conviction) for a common construct of interest, we would code effect sizes separately and then average them to a single effect size. In fact, this did not occur for any of the studies included in the final sample. To check whether differing definitions of recidivism systematically related to effect sizes, we subjected this to a moderator analyses and found no significant impact (see results section).

Some studies reported separate results for different offender types or risk groups, but did not meet criteria for independent comparisons as defined above. Here, we calculated effect sizes separately for the subgroups and used the weighted average to obtain a study effect size (see Fleiss 1994).

Whenever possible, participants who dropped out of treatment were included in the treatment group (“intent to treat” analysis).

Integration and statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted on the natural log of the OR (Fleiss 1994; Lipsey and Wilson 2001). To integrate effect sizes, we applied the weighting procedures based on the standard error of individual effect sizes (Hedges and Olkin 1985). Because of the expected heterogeneity of effect size distributions, we applied a random effects model. All moderator analyses were carried out under the assumption of a mixed effects model (see also Lipsey and Wilson 2001; Wilson 2001). The random variance component (τ2) was estimated via the method-of-moments procedure. Data were inspected for outliers and when necessary analyses were controlled for the presence of outliers and extreme values. Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics using the macros for meta-analysis written by David Wilson (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001).

Description of the study pool

Table 1 contains an overview of the basic characteristics of included comparisons. They were predominantly reported in the last two decades. Nearly half have appeared since 2000 and only four studies were dated before 1990. Due to the lag between treatment and outcomes that is required in follow-up studies, the time of treatment implementation was often considerably earlier. Although there is a range of countries where the studies took place, more than half came from North America. The majority of the comparisons were extracted from published journal articles. However, as mentioned, we took effort to include unpublished studies and these constituted almost one-fourth of the pool.

Treatment characteristics

The studies almost exclusively addressed the evaluation of cognitive-behavioral treatments (CBTs). Only eight programs were classified in other categories. In contrast to our previous meta-analysis (Lösel and Schmucker 2005), no study on hormonal treatment met the more rigorous inclusion criteria of the present meta-analysis. However, some of the programs in the current pool applied additional medication in individual cases. Treatment took place in institutional as well community settings and all but three programs were specifically designed for sexual offenders.

We coded whether treatment occurred in group and/or individual sessions on a 5-point scale. In most programs, treatment was solely (k = 9) or mainly (k = 8) carried out in a group format. Eight programs (27.6 %) contained predominantly individual sessions.

The duration of treatment ranged from a minimum of 8 weeks to a maximum of 281 weeks (M = 73.34, SD = 69.21, Median = 37.5). Obviously, the treatment length differed between settings, with outpatient treatment having the shortest durations (M = 52.54, SD = 41.58, Median = 30.8) and treatment in prison settings the longest (M = 98.50, SD = 91.24, Median = 78.0). The length of treatment could not be determined in 9 cases, that is, almost one-third of the studies did not provide information on a very basic variable.

Some features of the interventions were not well documented. Especially, coding of treatment integrity was rarely possible and if so, this mostly meant that studies reported positive indicators for treatment integrity. Only one study (Hanson et al. 2004) reported problems in implementing the treatment, but in 18 studies (62.1 %) there was simply no information on this aspect. It was also rarely reported whether aftercare services had been offered.

Offender characteristics

Regarding the age of the treated offenders, a majority of programs addressed adults only. However, this information could not always be extracted with sufficient certitude. The mean age of the treated offenders across all comparisons was 31.13 years (SD = 7.97). Usually, the samples were rather homogeneous in age, but again this aspect was not always clearly reported.

With regard to sexual offending, nearly half of the programs and evaluations included mixed groups of rapists and child molesters (k = 14). Sometimes, other sexual offenders also participated in the program (k = 6). Only one comparison referred to rapists and another one exclusively to exhibitionists. Seven comparisons only included child molesters and/or incest offenders. For eight comparisons, no further account for offense type (apart from being sexual offenders) was available.

Meta-analyses on general offender treatment have shown that the risk of recidivism is negatively related to effect size (e.g., Lösel 2012). Therefore, we tried to estimate the mean risk of treated offenders for each comparison. Mostly, proper risk assessments were not conducted or reported in the studies. However, many studies reported some information on variables that are relevant for risk. We used the Rapid Risk Assessment for Sex offense Recidivism (RRASOR; Hanson 1997) to evaluate this information. The RRASOR was originally designed for individual risk judgments. We used the items of the RRASOR to estimate the mean risk for the treated group by translating group statistics of the relevant variables (information on prior convictions, age distribution, and victim characteristics in the study sample) into item scores and added them up to the total score. This was possible for 17 comparisons (M = 1.98; SD = 0.63 across comparisons). We then recoded these scores into three risk categories with low risk ranging to a score of 1.5 and the high-risk category starting at a score of 2.5. According to recidivism data reported by Hanson (1997) and Doren (2004), this renders a low-risk group with estimated 5-year recidivism rates of roughly below 10 %, a medium-risk group with estimated 5-year recidivism rates between approximately 10 % and 20 %, and a high-risk group with estimated 5-year recidivism rates of about 20 % and above. Three comparisons reported other risk assessments that could also be grouped in these categories. Another four comparisons provided information that allowed an approximate risk classification. Table 1 shows the risk classification for those 24 comparisons. Five comparisons did not allow for any risk estimate. One might argue that our high-risk category does not represent the offenders at very high risk and could be termed “elevated risk” or high–medium risk as is done in some studies. However, our risk scores do not refer to individual offenders as in practical risk assessments, but are only used for a rough differentiation between groups as a whole. Against this background, we assume that the comparisons in our high-risk category will contain a substantial proportion of offenders at highest risk.

Methodological characteristics

Sample sizes ranged widely between a very small sample of 16 (Borduin et al. 1990) and a very large sample of 2,557 (Friendship et al. 2003). On average, studies included 358 (SD = 586.73) offenders, but in fact more than half of the comparisons (51.7 %) included fewer than 150 participants (Median = 136).

Only about one-fifth of the comparisons were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and studies with matching procedures to ensure equivalence of treated and untreated offenders were also rare. More than half of the comparisons drew on incidentally assigned samples. Most studies had a rather long follow-up period. The mean time at risk ranged from 12 to 234 months with 24 comparisons (82.8 %) reporting follow-ups of more than 3 years. On average, the follow-up time was 70.26 months or 5.9 years. Except for one study (Robinson 1995), all reported sexual recidivism as an outcome. Most commonly, recidivism was defined as a new conviction but other definitions such as re-arrest, new charges or reincarceration were also used. Three studies integrated different indicators to establish whether or not a new offense had occurred.

We also coded what Lösel and Köferl (1989) introduced as “Descriptive Validity” (DV) of an evaluation (see also Farrington 2006; Gill 2011). This is not a characteristic of the study method itself but refers to the accuracy of information provided in a research report. Overall, there was often a lack of information and clarity about the treatment evaluated and details regarding the population and methods used. On a scale from 0 (very low) to 3 (excellent) the overall transparency was on average 1.21 (SD = 0.68). The descriptive validity was especially low for reporting on the actual implementation of the treatment at hand (M = 0.48; SD = 0.69), which points back to the high amount of missing information regarding treatment integrity. For other areas, the documentation was better, but not ideal (DV for “treatment concept”: M = 1.41; SD = 0.91; DV for “evaluation methods”: M = 1.48; SD = 0.74). Only outcome reporting had better values regarding DV (M = 2.38; SD = 0.98); however, this was due to our eligibility criteria as studies that did not allow for a reasonably accurate estimate of effect size were not included.

Total effects

Of the 29 comparisons included in the analyses, 28 reported on sexual recidivism outcomes (Table 2). Figure 1 gives an overview of the individual ORs and confidence intervals for these comparisons as well as the overall mean. The forest plots show considerable differences between effect sizes and this heterogeneity was significant; Q (df = 27) = 52.05, p < .01. According to Higgins et al.’s (2003) I2-measure, nearly half of the observed heterogeneity cannot be attributed to sampling errors but represents systematic differences between the studies. Integration of the results according to a random effects model revealed a highly significant mean OR of 1.41 (p = .005). The treated offenders recidivated sexually at a mean rate of 10.1 % (n-weighted average). The mean OR indicated that without treatment the recidivism rate would have been at 13.7 %, that is, treatment reduced recidivism by 3.6 percentage points or 26.3 %.

Too few studies reported on violent (k = 7) or non-sexual recidivism (k = 7) to allow for adequate integration on these outcomes. However, 13 comparisons presented data on general recidivism (see Fig. 2). As in sexual offending, there was considerable and significant heterogeneity across outcomes in general recidivism; Q (df = 12) = 23.66, p = .03. The mean effect size was OR = 1.45 (p = .002). In terms of recidivism rates the n-weighted average in general reoffending for the treated groups was 32.6 %. According to the estimated mean effect, the respective rate would be at 41.2 % without treatment. This is a reduction of 8.6 percentage points or 26.4 % in general recidivism.

Sensitivity analyses: exclusion of outliers

The forest plots of Figs. 1 and 2 suggest that the significant heterogeneity might be due to outliers. In order to test the robustness of the effects, we supplemented the calculation of the total effects with an analysis excluding extreme values. To identify outliers, we drew on the procedure developed by Huffcutt and Arthur (1995) for meta-analysis. This takes into account the extremeness of a value (i.e., its deviation from the grand mean) as well as the respective sample size. For small samples, larger deviations may be expected by chance, while for larger samples even small deviations can be unlikely (i.e., “extreme”) and considerably influence results. For every study, the Sample-Adjusted Meta-Analytic Deviancy (SAMD) statistic was calculated, both with respect to effects in sexual and general recidivism. For sexual recidivism three effects stood out from the other effect sizes (Borduin et al. 2009; Greenberg at al. 2002[a]; McGrath et al. 1998). Excluding those comparisons from the integration resulted in a marginally lower mean OR of 1.38 (compared to the original 1.41). This effect was still significant at p = .003. While the effect size distribution became more homogenous with the outliers excluded (I2 = 35.4 %), it was still significantly heterogenous, Q (df = 24) = 37.18, p = .05. For any recidivism, one study showed an extreme value (Borduin et al. 2009). Excluding this reduced the total effect to OR = 1.40 (compared to the original 1.45). Again, the effect remained significant at p = .001, and heterogeneity was reduced (I2 = 32.7 %), Q (df = 12) = 17.83, p = .12.

Overall, our sensitivity analysis showed that the mean effect sizes were relatively robust. As the effect size distribution for sexual recidivism remained heterogeneous, a more differentiated analysis of moderator effects was carried out.

Moderator analyses

The moderator analyses were based on a mixed effects model. Due to the rather small number of comparisons, those analyses suffer from low statistical power. Nevertheless, it seemed worthwhile to explore on variables that may systematically influence the results because this is relevant for a more detailed future development of sexual offender treatment. Table 3 gives an overview of methodological, offender and treatment variables and their impact on differences between study results.

Methodological variables

As we included studies that used different definitions for recidivism, we tested whether the recidivism measure used would be related to systematic outcome differences. At Q (df = 4) = 2.94, p = .57, there was no significant impact on study effect sizes and the heterogeneity of the effect size distribution was not reduced when applying this characteristic as a moderating variable.

Overall, design quality had no systematic effect on results. Neither the comparison between randomized and quasi-experimental designs nor the more differentiated distinction according to the Maryland Scale yielded any significant differences regarding mean effects (p = .80 and p = .94, respectively) and the correlation between study effect size and methodological quality was minuscule (r = –.06, p = .73). However, the effect of treatment was statistically significant only for the designs at Level 3 of the Maryland Scale. For the few RCTs, the effect was a bit smaller and not statistically significant. This may be mainly due to the low number of RCTs. Another reason, however, is the enormous heterogeneity among randomized trials, Q (df = 4) = 14.39, p < .01 (see also Fig. 1). While the two randomized studies on multisystemic therapy (MST) of juvenile offenders (Borduin et al. 1990, 2009) showed extraordinarily strong treatment effects, the remaining three trials revealed weak to even negative results (Marques et al. 2005; Ortmann 2002; Romero and Williams 1983).

Although general recidivism outcomes were not the target of our moderator analyses, it should be noted that these showed a different picture with regard to methodological quality (see Fig. 2). Here, there was a significant difference between randomized and non-randomized designs, Q (df = 1) = 5.91, p = .02. RCTs had a strong treatment effect (k = 4, OR = 3.46, p = .001), whereas quasi-experimental designs revealed no significant outcomes (OR = 1.30, p = .07). This reverse picture is obviously due to different subsets of primary studies. Those two randomized studies showing the worst outcomes for sexual recidivism (Marques et al. 2005; Romero and Williams 1983) did not present data on general recidivism. Marques et al. reported findings on violent recidivism, which showed even worse results (OR = 0.64). Therefore, we assume that if all randomized studies had reported on general recidivism the effect would have been much smaller than mentioned above.

Recidivism base rate—defined as the mean recidivism rate in TG and CG—was an important moderator. The higher the rate of reoffending in a study sample, the larger the resultant effect sizes (r = .39, p = .02). This is in fact closely related to the a priori risk of treated offenders with higher risk (see section on “Offender variables”).

There were no systematic differences due to the length of follow-up. However, two counteracting processes may be reflected in this variable. On the one hand, longer follow-up periods are logically related to higher recidivism rates (in our sample: r = .35). Recidivism outcomes thus have a higher range in which effects can be demonstrated. On the other hand, the longer the follow-up, the more other influences come to work in the life of a treated offender, thus supposedly reducing the impact of treatment. Following these thoughts, we calculated a partial correlation between effect size and length of follow-up with control for the recidivism base rate. It showed a clearer albeit still not significant negative trend (r = –.27, p = .14; corrected for outliers: r = -.39; p = .052).

Analyses on sample size also revealed complex results. There was only a small and non-significant linear relation to treatment effects with larger samples doing slightly worse (r = –.05, p = .77). Eliminating the particularly large studies with n > 1000 (Duwe and Goldman 2009; Friendship et al. 2003) raised the correlation, which remained non-significant though (r = –.19, p = .30). However, as Table 3 shows, there is one category that clearly stands out: Studies with small samples (n ≤ 50) had very strong effects compared to all larger samples (p = .001). Among the comparisons with larger samples, there was no systematic relationship between sample and effect size (r = .14, p = .50).

The strongest moderating effect in the methodological domain was with regard to descriptive validity (quality of reporting on the study). The 4-point scale rating of DV correlated with effect size at r = .46, p = .01, indicating that unsatisfactory reports went along with worse outcomes. A closer inspection showed that this was mainly due to imprecise reporting on the treatment concept (p = .01) and the evaluation outcomes (p = .02). While the latter is probably related to conservative effect size estimation procedures, the former aspect may point towards treatment integrity.

There was no difference in mean effects with regard to publication type, Q (df = 2) = 2.59, p = .27, or publication status, Q (df = 1) = 0.01, p = .94.

Treatment variables

The analyses on the treatment characteristics showed a significant effect for the general treatment concept applied. This is mainly a function of two evaluations on MST which demonstrated very large effects. Repeating the analyses on differences between the general treatment approach without those two studies revealed a non-significant result, Q (df = 2) = 0.51, p = .78. Of the remaining treatment approaches, cognitive–behavioral treatments also showed a modest but significant effect on sexual recidivism. Other psychotherapeutic approaches did not yield a statistically significant treatment effect. This may be due to the low number of studies conducted on such therapies. The time of treatment implementation does not make a difference. There is no indication that treatment effects became larger in more recent time.

As Table 3 shows, there are only a few treatment features that clearly differentiate effective treatment. This is in part due to the few comparisons available for moderator analyses and the low power of the respective tests. However, there are some other findings that deserve mentioning. For example, while there was no clear indication of effect size differences across different settings (p = .16), we only found significant effects for outpatient treatments and those provided in hospitals. Treatment in prison settings yielded a lower and non-significant mean effect. Also, both the comparisons of specialized (versus non-specialized) sex offender treatment and authors’ affiliation with the treatment showed no significant moderator effect. But when testing the individual categories, only treatment tailored for sexual offenders and only evaluations conducted by authors affiliated with the treatment revealed significant mean effects in sexual recidivism.

There was a rather clear trend for better treatment effects of programs that had a more individualized approach (r = .41, p = .01). In part this was due to the two trials on MST which represent a highly individualized approach. However, there remained a considerable tendency after exclusion of those studies (r = .31, p = .09).

Treatment duration did not play a role regarding effect size; there was even a non-significant negative relation (r = –.15, p = .47). Controlling for different settings, outliers, or offender risk did not substantially alter this picture.

Offender variables

Most studies lacked a detailed description of offender variables or their analyses were not differentiated enough to allow for a detailed investigation of their impact on effect size. For example, we could not even perform a sensible analysis regarding the type of offense committed. Therefore, only three offender variables have been looked at in detail.

Regarding offender age, there was a significant treatment effect for both adults and adolescents. Although treatments that refer to adolescents fared somewhat better than those for adults, this difference was not significant (p = .17). If the analysis drew on the mean age of the treated participants, there was a tendency for younger groups benefiting more from treatment (r = –.30; p = .07). However, this was mainly due to the two evaluations of MST that targeted adolescents. Excluding these, the age effect disappears (r = –.11; p = .55). Another result refers to treatment recruitment (motivation). It made no difference whether offenders entered treatment voluntarily or on a mandatory basis (OR = 1.33 vs. OR = 1.32).

One of the strongest moderating effects is related to the risk of reoffending. The higher the risk for reoffending, the higher the resulting treatment effect. Treatments for low risk participants showed no effect at all. For the three risk categories there was a strong linear relationship (r = .46, p < .001) and the results proved rather stable against outlier corrections. However, it must be noted that our risk classification is only a rough estimate and only three studies fitted into the highest category. Therefore, the results should be read with caution at the upper end of offender risk.

Discussion

The above meta-analysis revealed a significant mean odds ratio of 1.41 for sexual recidivism. Only 10.1 % of treated offenders reoffended whereas without treatment the recidivism rate would be 13.7 %. That is a difference of 3.6 percentage points or 26.3 %. For the more general outcome of any recidivism, the mean effect was in the same range, even somewhat higher. Excluding outlier results only slightly reduced the mean effects and they remained significant, both for sexual and any recidivism outcomes. Thus, the total effects seem to be robust. Drawing on a sample of 29 rather well-controlled comparisons, the results suggest that treatment can effectively reduce recidivism in sexual offenders.

The present mean effect in sexual recidivism is smaller than the one we found in our previous meta-analysis, which included 80 comparisons, many of which contained non-equivalent untreated groups (OR = 1.70; Lösel and Schmucker 2005). However, the previous review also incorporated studies on surgical castration and pharmacological treatment. Studies on surgical castration showed very large effect sizes but had various methodological shortcomings (apart from ethical and legal problems of the intervention itself). Excluding those studies, the mean OR in our previous review was 1.38, and when the analyses were restricted to just psychosocial interventions it further decreased to OR = 1.32. As only psychosocial interventions fulfilled the stricter eligibility criteria in the current meta-analysis, the present mean effect is even a little stronger than in the previous meta-analysis.

Although the overall results suggest a desirable effect of treatment, this cannot be easily generalized because of the considerable heterogeneity in the findings of the primary studies. In addition, only six studies (five with sexual offending as outcome) were RCTs. Eight further studies at least used individual matching procedures to render equivalence between treatment and comparison groups. Although the effect size of those studies was in the same range as for the methodologically weaker studies, both the RCTs and the studies with individual matching failed to yield statistical significance. In both cases, this may be due to low statistical power (few studies and often only small sample sizes). The RCTs also showed very heterogeneous results, which further reduces statistical power. Obviously, there is no unambiguous trend in the best studies available. Accordingly, more RCTs are needed in order to get more valid data on the true effects of sexual offender treatment. On the other hand, one should consider the arguments of Marshall and Marshall (2007) against a too narrow focus on RCTs in this field; for counter-arguments, see Seto et al. (2008). A RCT that is not adequately designed to address the practice of psychotherapy may have limited value (e.g., Hollin 2008; Seligman and Levant 1998) and various threats to internal validity may also occur in RCTs (e.g., Lösel 2007). Therefore, we suggest increasing the number of RCTs on sexual offender treatment. But when an adequately designed RCT is not feasible, one should also apply sound quasi-experimental designs that have been recommended since Campbell’s (1969) groundbreaking article in the field of program evaluation (e.g., Shadish et al. 2002).

The basic evaluation design was not a significant moderator in our meta-analysis. This is in contrast to findings in other fields of criminology (Weisburd et al. 2001), but not an exception in offender treatment research (Lipsey and Cullen 2007; Lösel 2012). In the present meta-analysis, other methodological features had a clearer influence on effect sizes. For example, one-third of the evaluations had only small sample sizes with up to 50 offenders. Those had higher effects than evaluations based on larger samples. This is usually regarded as a sign of publication bias. However, it should be noted that the difference in the present meta-analysis was not a function of an evaluation being published or not. First, publication status did not exert any influence on effect size. Second, the small sample effect was visible in published as well as unpublished studies. It is possible, though, that there is an “internal” publication bias, that is, it may be more difficult to “hide” the results of a larger study. In contrast, the results of small-scale studies may never be reported at all, not even as an unpublished report, especially if those results are negative and the researcher has a strong interest in not making the results visible. In fact, only one of the unpublished studies drew on a small sample (14 %) compared to 30 % among published studies.

An alternative explanation of the small sample effect may be that treatment implementation is better monitored and easier controlled in a small-scale setting. There are some other findings in our review that fit well with this implementation hypothesis: Evaluations that focused on only one program implemented in one location revealed somewhat better results than studies that evaluated different programs across different institutions. Usually, the latter indicates that program implementation was not well controlled (Greenberg et al. 2002; Ruddijs and Timmermann 2000) or that it was in fact weak (Hanson et al. 2004). Only two of the multi-location evaluations indicated a well-controlled implementation (Friendship et al. 2003; Guarino-Ghezzi and Kimball 1998). Those two showed relatively good outcomes among the multi-location evaluations. Also, model projects that can be assumed to have a tight grip on program implementation fared slightly better than routine applications of treatment. This is in accordance with the literature on general offender treatment (Lösel 2012).

The finding that only evaluations by authors affiliated to the program is in accordance with other criminological findings (Eisner 2009; Petrosino and Soydan 2005). On the one hand, this could be a matter of treatment integrity: It is likely that those who evaluate their own work pay more attention to proper program implementation. In fact, three-quarters of the comparisons showing positive indicators of treatment integrity come from authors affiliated with the program in some way. On the other hand, authors affiliated with the treatment may also be more reluctant to report negative results, although the current data do not lend much support to this assumption: There was no noteworthy interaction between author affiliation and publication status. But again, these results only refer to reports that were made available to us and there might be a “hidden” publication effect that goes beyond “officially published or not.” Overall, there was not enough valid information on treatment implementation and therefore this topic could not be properly tested.

Insufficient information in the documentation of details of the evaluation was very common in the current study set. This problem hinders more detailed moderator analyses and is in itself related to treatment effects. Studies that had more shortcomings in their reports showed lower effects than the better documented studies. The correlation between documentation quality and effect size can be tracked down to two aspects. First, it is a consequence of outcome reporting. Whenever possible effects were estimated for a comparison, but sometimes data had to be partially reconstructed from what was reported in a study. To ensure that the reconstruction would not overestimate the effects, this was done in a conservative manner, so smaller effects in those comparisons could be expected. The second, and probably stronger, influence regarding the quality of documentation comes from the lack of detail on the treatment concept under consideration. The clearer a treatment concept was documented, the higher the treatment effect. Again, this underlines the importance of treatment integrity. One can assume that in those cases that did not sufficiently report on the treatment, the concept may have been less elaborated or not properly implemented. Although this interpretation is somewhat speculative, the issue of descriptive validity should be seriously taken into account in future research.

The influence of methodological variables reduces the power to detect important content variables or may be confounded with such variables (Lipsey 2003). Due to the limited number of available comparisons, a meaningful statistical control for confounded variables was not possible in this meta-analysis. In spite of these limits, there are some moderating effects related to more specific variables that deserve further attention.

Various treatment concepts that are used in practice were only represented by single studies or not at all. For example, no evaluation of pharmacological treatment fulfilled the eligibility criteria for our study pool. With regard to cyproterone acetate (CPA) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), we found no controlled studies that examined their effectiveness on sexual offender recidivism. With regard to medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), there are at least some controlled studies. However, these evaluations mostly draw upon non-equivalent control groups and none of them fulfilled the criteria for the current review. To our knowledge, there is one RCT on MPA treatment with sexual offenders (McConaghy et al. 1988). But with regard to the recidivism outcomes, the randomized design is so severely disturbed that it renders the groups clearly non-equivalent. The RCT only holds for a less strict outcome criterion (“reduction in anomalous behavior”) that was not eligible for the present analysis. While other meta-analyses found favorable effects for hormonal medication (Hall 1995; Lösel and Schmucker 2005), these effects were based on weakly designed studies. It is therefore essential that the promising findings from previous meta-analyses be confirmed in evaluations with stronger research designs.

Only evaluations of psychosocial treatments met the inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis. Among the various psychotherapeutic approaches, one approach stands out: The two evaluations on multisystemic therapy (MST) for juvenile sexual offenders showed extraordinarily strong effects and differed significantly from other approaches. However, the results on MST have to be interpreted with caution. Apart from the basic treatment concept, both studies had other features that are connected with higher effects in the moderator analyses: They targeted young and rather high-risk adolescent offenders, contained small samples, and controlled for treatment integrity. In addition, both studies were conducted by the program developers themselves. Our positive results on MST correspond to findings in general offender treatment (Curtis et al. 2004). However, those studies are predominantly internal evaluations by the program developers. In addition, Curtis et al. found that the effects for multisystemic treatment were especially high in efficacy studies (demonstration projects) compared to effectiveness studies in real practice. When Littell et al. (2005) conducted a review on MST, they drew a more skeptical picture because they only identified one fully independent evaluation and this showed no positive effect. Littell et al.’s critical conclusions have been challenged on theoretical and methodological grounds (Henggeler et al. 2006). However, independent evaluations of MST in Scandinavia also showed partially contradicting effects (Ogden et al. 2007; Sundell et al. 2008). Therefore, one may conclude that the two MST studies on sexual offenders in the current review show very promising results, but these need replication in independent evaluations.

The majority of evaluations in the present study pool addressed cognitive-behavioral treatments (CBTs). Although CBT is not at all a homogeneous concept (Marshall and Marshall 2010), there is a relatively broad study base to draw conclusions. The 20 comparisons evaluating sexual recidivism showed a significant, albeit moderate mean effect. This is in line with most of the previous meta-analyses on sexual offender treatment (e.g., Hall 1995; Hanson et al. 2002; Lösel and Schmucker 2005) and on general offender treatment (Landenberger and Lipsey 2005; see also Lösel 2012). Other approaches did not reach significant effects. In fact, there were hardly any evaluations of other treatment approaches that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. However, even among the CBT approaches, the effects varied considerably and the only RCT on CBT that reports sexual recidivism outcomes (Marques et al. 2005) did not show a positive treatment effect. Although CBT approaches have been advocated over the last decades, the effects are not as clear cut as one might wish for “best practice” approaches. It seems that the principal treatment approach in itself is not the clearest moderator and other variables may be more relevant for outcome differences.

Many of the treatment-related variables in the current meta-analysis did not provide clear cut differences between evaluations. However, there was a tendency that outpatient treatment fared better than treatment in prisons. The difference in favor of community programs is in agreement with the general research on ‘what works’ in correctional treatment (e.g., Andrews and Bonta 2010; Koehler et al. 2013; Lipsey and Cullen 2007; Lösel 2012; Lösel and Koehler 2014). This may be due to iatrogenic ‘contamination effects’ in the prison subculture, a lack of deterrence, a deferred transfer of learned contents to the world outside, difficulties during resettlement and other influences (Durlauf and Nagin 2011; Gatti et al. 2009; Lösel et al. 2012; Markson et al. 2015). Our results on prison-based treatment are relevant for practice but they are difficult to interpret. Although there was no significant mean effect, prison-based programs also did not fare significantly worse than treatment in other settings. Therefore, some issues of treatment context need to be emphasized. First, the primary studies did not directly compare treatment in prison versus in the community, but TGs and CGs within the prison context. Second, institutionalized treatment in hospitals showed a significant effect on sexual reoffending. Third, one of the few primary studies in our pool that demonstrated a significant result was a prison-based CBT program (Duwe and Goldman 2009: OR = 1.46). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate what program, organizational, relational and offender differences can make sexual offender treatment in prisons more promising.

One relevant issue may be the treatment format. In practice, sexual offender treatment for the most part takes place in groups. In a thorough discussion, Ware et al. (2009) provide plausible arguments for this approach. Not least, practical and financial reasons have to be considered. However, our findings suggest that the inclusion of individual sessions reveals better results. There may be confounding variables at work. For example, excluding the MST evaluations reduced the effect of individualization and the relationship is probably not fully linear, that is, a complete individualization may not be the golden principle either. However, it seems that supplementing group treatment with individualized sessions may better fit the responsivity principle of appropriate offender treatment (Andrews and Bonta 2010). Unfortunately, there is no systematic research on the question of whether an individualized or a group format is better for sexual offenders. However, there are various reasons for better effects of programs with individualized elements. First, some offenders may “hide” in group sessions. Second, using group sessions means that the same needs are targeted for all participants. This goes against the concept of individual needs and specific responsivity (Andrews et al. 2011), especially in mixed groups with very heterogenous offender types. Third, supplemental individual sessions allow the tailoring of treatment more specifically (Drake and Ward 2003) and strengthen therapeutic alliances (Marshall et al. 2003; Ward and Maruna 2007). Because general research on psychotherapy has clearly shown that relational issues and therapist characteristics are as important as the treatment model (e.g., Orlinsky et al. 1994), offender treatment needs to recognize that one size may not fit all (Lösel 2012). Accordingly, treatment manuals should provide sufficient scope for flexibility and innovation (Marshall 2009).

It would be desirable to more clearly disentangle the effect of the treatment format also for other variables; for example, there is no research on a standard versus rolling format. Unfortunately, our study pool is too small to allow for analytical models enabling us to control for confounding variables in a more appropriate manner. In our previous meta-analysis, which had less strict inclusion criteria and thus a bigger study pool, we could control for a number of other variables. As a consequence, the impact of group versus individual treatment was less clear when we applied hierarchical regression analyses (Lösel and Schmucker 2005). Therefore, at this stage, we recommend further investigation of whether or not individualization is connected to better treatment outcomes. This kind of research should be related to analyses of the influence of other treatment process variables (see also Harkins and Beech 2007; Pratt 2010).

Regarding offender characteristics, there is a trend for younger sex offenders to gain more from treatment. Again, this has to be interpreted with caution due to possible confounding variables. For example, younger offenders are also at higher risk for reoffending. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that early interventions in the career of sexual offenders are particularly worthwhile. The treatment of adolescent or young adult offenders can also benefit more from protective factors in the family or natural social context (Lösel 2012).

The risk of reoffending was the strongest predictor of a positive treatment effect in the current analysis. The result of better effects in offenders at higher risk is in line with experiences from general offender treatment (Lipsey and Cullen 2007; Lösel 2012). Hanson et al. (2009) applied the Risk–Need–Responsivity model to sexual offender treatment and found that programs were most effective when they fulfilled all three principles. The risk principle taken alone did not reach a significant result, but Hanson et al. rated the risk only dichotomously. Probably our more differentiated risk rating led to more homogeneous categories and therefore better statistical power. However, the category of ‘high risk’ in our review should be regarded cautiously because it does not mean that all these offenders were at very high risk. For example, psychopathic offenders, who would qualify as highest-risk groups, are particularly difficult to treat and often excluded from treatment programs (Lösel 1998). At the other end of the risk level, our findings suggest no significant effect. For offenders at low risk of reoffending, the recidivism rate is so small that treatment cannot add much to further reduce reoffending.

Another variable deserves attention because it failed to produce a moderating effect: voluntary versus non-voluntary treatment participation did not differ in their outcomes. Although the mean effect of studies with non-voluntary treatment was not significant, this seems to be mainly a consequence of low statistical power (only six comparisons fell into that category). In fact, the mean effect is just the same as with voluntary treatments and in both categories the outcomes are highly heterogeneous. This means that (1) offenders brought to treatment via external pressures such as judicial orders may benefit from treatment, and (2) that voluntariness in itself is not a sufficient condition for successful treatment. Our finding points to the important role of change motivation as a process (e.g., Prochaska and Levesque 2002) and techniques such as motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick 2002). Unfortunately, treatment descriptions were not detailed enough to code and analyze this issue in more detail.

Taken together, the above analyses of reasonably well-controlled evaluations suggest that treatment of sexual offenders can be effective, but the results are not homogeneous. In particular, treatment in prisons and pure group formats seem to be less promising. Our findings are also supported by several more recent studies that were not included in this review (see Appendix). However, there is still a lack of very high quality studies to unambiguously demonstrate treatment effectiveness. Future research must continue to critically evaluate sexual offender treatment in studies that use good research designs and are preferably independently authored and well documented. Sound documentation is important because this is the key to a more thorough understanding of causal mechanisms in treatment practice. Due to the heterogeneity between primary studies, the investigation of outcome moderators needs much more attention. For example, although there is much research on the characteristics and subtypes of sexual offenders, this is rarely taken into account in treatment evaluation. In addition, we need more research on the processes of therapy with sexual offenders (Marshall and Burton 2010) and focused tests of certain treatment features such as individualization, motivation and institutional context (Lösel 2012). There are also too few evaluations that investigate recidivism not only as a dichotomous category but also consider multiple criteria such as survival time, frequency and harm of the respective offenses (e.g., Olver et al. 2012). Instead of sweeping controversies about the effectiveness of sex offender treatment, more differentiated perspectives are needed (Koehler and Lösel 2015). As is common in other areas of therapy and psychosocial interventions, research and practice should ask more frequently what works with whom, in what contexts, under what conditions, with regard to what outcomes, and also why. Although our review does not provide definite answers to such differentiated questions, it suggests that sexual offender treatment has made progress towards an evidence-oriented crime policy.

Notes

Carrying out and publishing a comprehensive meta-analysis takes a lot of time. Therefore, trying to keep a review updated can create a vicious cycle that is in conflict with timely publication. We are aware of a few more recent studies that are not included in our review. We also know about two studies with large samples; however, after some waiting time, the latter findings have not yet been released. Therefore, we felt that the current analysis should now be published. To check the robustness of our findings, we assessed the available more recent studies and found that they were generally in accordance with our main results. The respective studies are briefly reported in the Appendix.

References

Abracen, J., Looman, J., Ferguson, M., Harkins, L., & Mailloux, D. (2011). Recidivism among treated sexual offenders and comparison subjects: recent outcome data from the Regional Treatment Centre (Ontario) high-intensity Sex Offender Treatment Programme. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 17, 142–152.

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct, 5th ed. Cincinatti: Anderson.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, S. (2011). The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model: does adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38, 735–755.

Barbaree, H. E. (1997). Evaluating treatment efficacy with sexual offenders: the insensitivity of recidivism studies to treatment effects. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 9, 111–128.

Campbell, D. T. (1969). Reforms as experiments. American Psychologist, 24, 409–429.

Corabian, P., Dennett, L., & Harstall, C. (2011). Treatment for convicted adult male sex offenders: an overview of systematic reviews. Sexual Offender Treatment, 6 (1), online journal.

Curtis, N. M., Ronan, K. R., & Borduin, C. M. (2004). Multisystemic treatment: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(3), 411–419.

Doren, D. M. (2004). Stability of the interpretative risk percentages for the RRASOR and static-99. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16, 25–36.

Drake, C. R., & Ward, T. (2003). Practical and theoretical rules for the formulation based treatment of sexual offenders. International Journal of Forensic Psychology, 1, 71–84.

Durlauf, S. N., & Nagin, D. (2011). Imprisonment and crime: can both be reduced? Criminology and Public Policy, 10, 13–54.

Eisner, M. (2009). No effects in independent prevention trials: can we reject the cynical view? Journal of Experimental Criminology, 5, 163–183.

Farrington, D. P. (2006). Methodological quality and the evaluation of anticrime programs. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2, 329–337.

Farrington, D. P., Gottfredson, D. C., Sherman, L. W., & Welsh, B. C. (2002). The Maryland scientific methods scale. In L. W. Sherman, D. P. Farrington, B. C. Welsh, & D. L. MacKenzie (Eds.), Evidencebased crime prevention (pp. 13–21). London: Routledge.

Fleiss, J. L. (1994). Measures of effect size for categorical data. In L. V. Hedges (Ed.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 245–260). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Freeman, N. J., & Sandler, J. C. (2008). Female and male sex offenders: a comparison of recidivism patterns and risk factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1394–1413.

Gatti, U., Tremblay, R. E., & Vitaro, F. (2009). Iatrogenic effects of juvenile justice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 991–998.

Gill, C. E. (2011). Missing links: how descriptive validity impacts the policy relevance of randomized controlled trials in criminology. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 201–224.

Grady, M. D., Edwards, D., Pettus-Davis, C., & Abramson, J. (2013). Does volunteering for sex offender treatment matter? Using propensity score analysis to understand the effects of volunteerism and treatment on tecidivism. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 25, 319–346.

Greenberg, D., Bradford, J., Firestone, P., & Curry, S. (2000). Recidivism of child molesters: a study of victim relationship with the perpetrator. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 1485–1494.

Hall, G. C. N. (1995). Sexual offender recidivism revisited: a meta-analysis of recent treatment studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 802–809.

Hanson, R. K. (1997). The development of a brief actuarial scale for sexual offense recidivism. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services of Canada.

Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2009). The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: a meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychological Assessment, 21, 1–21.

Hanson, R. K., Gordon, A., Harris, A. J. R., Marques, J. K., Murphy, W. D., Quinsey, V. L., & Seto, M. C. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14, 169–194.

Hanson, K., Burgon, G., Helmus, L., & Hodgson, S. (2009). The principles of effective correctional treatment also apply to sexual offenders: a meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 865–891.

Harkins, L., & Beech, A. R. (2007). A review of the factors that can influence the effectiveness of sexual offender treatment: risk, need, responsivity, and process issues. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12, 616–627.

Hasselblad, V., & Hedges, L. V. (1995). Meta-analysis of screening and diagnostic tests. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 167–178.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic.

Henggeler, S. W., Schoenwald, S. K., Swenson, C. C., & Borduin, C. M. (2006). Methological critique and meta-analysis as a Trojan horse. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 447–457.

Higgins, J. P. T., Simon, G. T., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ[British Medical Journal], 327(7414), 557–560.

Hollin, C. R. (2008). Evaluating offending behaviour programmes: does only randomization glister? Criminology and Criminal Justice, 8, 89–106.

Huffcutt, A. I., & Arthur, W. J. (1995). Development of a new outlier statistic for meta-analytic data. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 327–334.

Koehler, J, & Lösel, F. (2015). A differentiated view on the effects of sex offender treatment. British Medical Journal (eLetter), http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h199/rr-0.

Koehler, J. A., Lösel, F., Humphreys, D. K., & Akoensi, T. D. (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of young offender treatment programs in Europe. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9, 19–43.

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. (2005). The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: a meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 451–476.

Letourneau, E. J., Henggeler, S. W., McCart, M. R., Borduin, C. M., Schewe, P. A., & Armstrong, K. S. (2013). Two-year follow-up of a randomized effectiveness trial evaluating MST for juveniles who sexually offend. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 978–985.

Lipsey, M. W. (2003). Those confounded moderators in meta-analysis: good, bad, and ugly. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587, 69–81.

Lipsey, M. W., & Cullen, F. T. (2007). The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: a review of systematic reviews. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3, 297–320.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Littell, J. H., Campbell, M., Green, S., & Toews, B. (2005). Multisystemic Therapy for social, emotional, and behavioral problems in youth aged 10–17. 2005, Issue 4. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4.

Lösel, F. (1998). Treatment and management of psychopaths. In D. J. Cooke, A. E. Forth, & R. B. Hare (Eds.), Psychopathy: Theory, research and implications for society (pp. 303–354). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lösel, F. (2007). Doing evaluation in criminology: Balancing scientific and practical demands. In R. D. King & E. Wincup (Eds.), Doing research on crime and justice (2nd ed., pp. 141–170). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lösel, F. (2012). Offender treatment and rehabilitation: What works? In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminology (5th ed., pp. 986–1016). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lösel, F., & Koehler, J. (2014). Can prisons reduce reoffending? A meta-evaluation of custodial and community treatment programs. Presentation at the 14th Conference of the European Society of Criminology, 10–13 September 2014, Prague, CZ.

Lösel, F., & Köferl, P. (1989). Evaluation research on correctional treatment in West Germany: A metaanalysis. In H. Wegener, F. Lösel, & J. Haisch (Eds.), Criminal behavior and the justice system (pp. 334–355). New York: Springer.

Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 117–146.

Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2014). Treatment of sex offenders. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 5323–5332). New York: Springer.

Lösel, F., Pugh, G., Markson, L., Souza, K., & Lanskey, C. (2012). Risk and protective factors in the resettlement of imprisoned fathers with their families. Final research report. Norwich: Ormiston Children and Families Trust.

Mann, R. E., Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (2010). Assessing risk for sexual recidivism: some proposals on the nature of psychologically meaningful risk factors. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 22, 191–217.

Markson, L., Lösel, F., Souza, K., & Lanskey, C. (2015).Male prisoners’ family relationships and resilience in resettlement. Criminology and Criminal Justice, in press, online; doi:10.1177/1748895814566287).

Marshall, W. L. (2009). Manualization: a blessing or a curse? Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15, 109–120.

Marshall, W. L., & Burton, D. (2010). The importance of therapeutic processes in offender treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 141–149.

Marshall, W. L., & Marshall, L. E. (2007). The utility of the random controlled trial for evaluating sexual offender treatment: the gold standard or an inappropriate strategy? Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 19, 175–191.

Marshall,W.L., & Marshall, L.E. (2010). Can treatment be effective with sexual offenders or does it do harm? A response to Hanson (2010) and Rice (2010). Sexual Offender Treatment, 5 (2), online.

Marshall, W. L., Fernandez, Y. M., Hudson, S. M., & Ward, T. (Eds.). (1998). Sourcebook of treatment programs for sexual offenders. New York: Plenum.

Marshall, W. L., Serran, G. A., Fernandez, Y. M., Mulloy, R., Mann, R. E., & Thornton, D. (2003). Therapist characteristics in the treatment of sexual offenders: tentative data on their relationship with indices of change. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 9, 25–30.

McConaghy, N., Blaszczynski, A., & Kidson, W. (1988). Treatment of sex offenders with imaginal desensitization and/or medroxyprogesterone. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 77, 199–206.

McGrath, R. J., Cumming, G. F., Burchard, B. L., Zeoli, S., & Ellerby, L. (2010). Current practices and emerging trends in sexual abuse management: The safer society 2009 North American survey. Brandon: The Safer Society Press.

Miller, W., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Ogden, T., Hagen, K., & Andersen, O. (2007). Sustainability of the effectiveness of a programme of Multisystemic Treatment (MST) across participant groups in the second year of operation. Journal of Children’s Services, 2, 4–14.