Abstract

Collaboration between nonprofit and business sectors is widely regarded as a value creation process that benefits society, business, and nonprofit organizations (NPOs). This process, however, has rarely been considered from a nonprofit perspective. In this paper, we discuss a new framework to assist NPOs in developing strategic collaborations with businesses. We argue that, by being strategically proactive rather than reactive to what businesses might offer, NPOs can increase the scale of their cross-sector collaborations and thus enhance their sustainability. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Résumé

La collaboration entre le secteur à but non lucratif et les entreprises privées est souvent considérée comme un procédé de création de valeur qui bénéficie à la société, aux entreprises et aux organismes à but non lucratif (OBNL). Cependant, ce procédé a rarement été considéré du point de vue des organismes à but non lucratif. Dans cet article, nous proposons un nouveau cadre pour aider les OBNL à développer des collaborations stratégiques avec les entreprises. Nous soutenons que, en adoptant une approche de stratégie active plutôt qu’en attendant de réagir aux offres des entreprises, les OBNL peuvent accroître l’ampleur de leurs collaborations avec le secteur privé et améliorer ainsi leur durabilité. Nous évaluons l’impact de nos conclusions sur la recherche et la pratique.

Zusammenfassung

Die Zusammenarbeit zwischen dem Nonprofit- und dem Wirtschaftssektor wird weitestgehend als ein Wertschöpfungsverfahren angesehen, das der Gesellschaft, der Wirtschaft und den Nonprofit-Organisationen Nutzen bringt. Dieses Verfahren wird jedoch selten aus der Perspektive des gemeinnützigen Sektors betrachtet. In diesem Beitrag diskutieren wir ein neues Rahmenwerk zur Unterstützung der Nonprofit-Organisationen bei der Entwicklung strategischer Kollaborationen mit Wirtschaftsunternehmen. Wir behaupten, dass Nonprofit-Organisationen ihre sektorübergreifenden Kollaborationen erweitern und somit ihre Nachhaltigkeit erhöhen können, wenn sie strategisch proaktiv sind, statt lediglich auf die Angebote der Wirtschaftsunternehmen zu reagieren. Es werden die Implikationen für Forschung und Praxis diskutiert.

Resumen

La colaboración entre los sectores empresarial y sin ánimo de lucro se considera en general como un proceso de creación de valor que beneficia a la sociedad, a la empresa y a las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro (NPO, del inglés non profit organizations). Sin embargo, este proceso ha sido considerado raras veces desde la perspectiva de las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro. En el presente documento, abordamos un nuevo marco para ayudar a las NPO a desarrollar colaboraciones estratégicas con las empresas. Argumentamos que, siendo estratégicamente proactivas en lugar de reactivas a lo que las empresas pueden ofrecer, las NPO pueden aumentar la escala de sus colaboraciones intersectoriales e incrementar de este modo su sostenibilidad. Se abordan las implicaciones para la investigación y la práctica.

摘要

非营利部门和商业部门的合作被广泛视为可为社会、商业和非营利组织(NPO)带来效益的价值创造过程。然而,人们很少从非营利的视角看待这一过程。在本篇论文中,我们探讨一种协助 NPO 与企业构建战略合作关系的新框架。我们认为,对于企业在合作中为 NPO 提供何种帮助方面,NPO 需要采取战略主动行为,而不是被动对应,这样 NPO 可以扩大跨部门合作的规模,由此增强可持续发展能力。本篇论文还讨论了研究和实践的影响。

ملخص

التعاون بين القطاعات الغير ربحية والتجارية يعتبر على نطاق واسع كنهج قيم للإبداع الذي يعود على المجتمع بالفائدة، الأعمال التجارية، المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPOs). هذا النهج، مع ذلك، نادر˝ا ما يتم إعتباره من المنظور الغير ربحي. في هذا البحث، نحن نناقش إطار جديد لمساعدة المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPOs) في تطوير التعاون الإستراتيجي مع الأعمال التجارية. فإننا نجادل أن، تكون المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPOs) فاعلا˝ إستراتيجيا˝ بدلا˝ من أن تكون رد الفعل على ما قد تقدمه الأعمال التجارية، يمكن أن يزيد من حجم التعاون بين القطاعات، وبالتالي تعزيز إستدامتهم. تمت مناقشة الآثار المترتبة على البحث والممارسة.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Collaboration between organizations across different sectors has been described as a new approach to cope with complex social problems (Bryson et al. 2006; Guo and Acar 2005). In particular, Nonprofit-Business Collaboration (NBC) has proven to be a powerful means of addressing these problems (Austin 2000b; Rondinelli and London 2003). NBC, also referred to as cross-sector social-oriented partnerships (Selsky and Parker 2005) and Corporate-NPO collaboration (Simpson et al. 2011), has notable attributes. First, the collaboration should cross-sector boundaries to involve organizations from nonprofitFootnote 1 and business sectors (i.e., NBC typically does not involve the government sector). Second, each partner should be able to deliver value to the other (Austin 2000b). Third, a common objective(s) should underpin the collaboration, which, generally, should be the creation of positive social change (Bies et al. 2007). We, therefore, define an NBC as a discretional agreement between an NPO and a for-profit business to address social or environmental issues and to produce specific organizational benefits for both partners.

Research into this relationship is extensive and typically relates to two lines of inquiry. The first line seeks to understand NBC as a chronological process and to explore how NBC delivers its planned objectives (e.g., Austin 2000b; Bryson et al. 2006; Koschmann et al. 2012; Rondinelli and London 2003; Selsky and Parker 2005; Waddock 1989; Yaziji and Doh 2009). The second line of inquiry concerns the suggestion that businesses can utilize the collaboration with the nonprofit sector as a vehicle to implement social responsibility programs (e.g., Dahan et al. 2009; den Hond et al. 2012; Holmes and Smart 2009; Kourula 2009; Yaziji 2004; Porter and Kramer 2002). It is argued that, through collaborations, businesses can achieve two aims simultaneously: to contribute toward solving society’s problems (i.e., create social value) and to deliver economic gains (i.e., create financial value). NPOs possess a set of distinctive advantages necessary to attain these aims. Typically, NPOs have strong legitimacy and public trust, are deeply embedded within society and hence aware of influential forces in the community (e.g., NPOs often understand how public opinion is formulated and influenced by active social movements), and have a unique capacity and expertise to address social and environmental concerns (den Hond et al. 2012; Elkington and Fennell 2000; Yaziji 2004). It is evident, however, that little attention has been paid to examine NBC from the nonprofit sector perspective (Harris 2012) or how NPOs can maximize their benefits from collaboration with businesses.

NPOs are operating in a constrained environment, where maintaining their economic viability and growth has become a critical issue (Weerawardena et al. 2010). This challenge has been driven by several factors including an escalation of competition in the nonprofit sector (Phillips 2012), coupled with a growing number of new entrants to this sector (Chew and Osborne 2009b), shrinkage of as well as uncertainty about government funding (Bingham and Walters 2012), and a reduction of traditional philanthropic income sources (McAlexander and Koenig 2012). Such conditions have induced NPOs to explore new approaches to maintain their services while remaining sustainable (Weerawardena et al. 2010). We contend that NBC is a worthwhile strategic choice for NPOs that can support NPOs’ sustainability in a number of ways, including generating new income streams, knowledge and skills transfers, and publicity (Andreasen 1996; den Hond et al. 2012).

In this paper, we present a conceptual framework combining several factors to guide the development of an NBC strategy from the nonprofit perspective. More specifically, the framework is synthesized using (1) the three elements of strategy (context or the environment in which an organization operates; content or the choices to achieve the strategy purpose; and process or the formulation and implementation of the chosen strategy) (Pettigrew 1985; Pettigrew and Whipp 1991), (2) concepts from stakeholder theory, and (3) aspects from the nonprofit and cross-sector collaboration literature. It is important to note that, in this paper, we are not describing a specific strategy for NBC; rather, the aim is to unfold factors that can influence strategy development.

We divide the paper into three main sections. First, we discuss the three overarching elements of strategy, which underpin the conceptual framework. Second, we present and discuss the conceptual framework, including a series of propositions. Finally, we conclude with a discussion about the potential risks and challenges of NBC and the implications of the framework for future research and practice.

The Three Elements of Strategy

In the area of strategic management, it is widely asserted that context, content, and process elements determine the final shape of a strategy (Pettigrew 1987; Wit and Meyer 2010) and predict the strategy’s performance (Ketchen et al. 1996). Importantly, Pettigrew (1987) argues that organizations can achieve strategic change by addressing these elements simultaneously, and Ketchen et al. (1996) found that process and content elements can predict an organization’s performance, with context acting as a moderating factor. Accordingly, these elements constitute the building blocks of our conceptual framework because they are central in explaining the effects of strategy on organizational performance over time (Pettigrew and Whipp 1991).

The context element concerns the pre-existing conditions and forces in the environment in which an organization operates. Pettigrew (1985) suggests that a better understanding of organizational context can be achieved by dividing the context into an outer and an inner context. The outer context, over which the organization has less control, includes issues such as social, economic, and competitive conditions. The inner context concerns aspects such as corporate culture, structure, and organizational policies. The content element relates to the strategic options, directions, and practices an organization aims to adopt to achieve its planned objectives (Moser 2001; Wit and Meyer 2010). For businesses, the content concerns a company’s response to the forces in the industry context such as competitors, buyers, and suppliers (Porter 1996). Better reacting to and/or predicting these forces is likely to result in a better inter-fit (alignment between an organization and its working environment) and intra-fit (internal coherence across an organization’s resources, politics and planned strategy), leading to higher performance (Ketchen et al. 1996). Finally, the process element relates to the management of activities, actions, and methods concerned with how a strategy (content element) is formulated and implemented in a given context (Huff and Reger 1987; Pettigrew 1997). In addition, Miles et al. (1978) note that a strategy process is significantly influenced by the context of a strategy, as Pettigrew (1992, p. 10) comments that “context is not just a stimulus environment but a nested arrangement of structures and processes where the subjective interpretations of actors perceiving, learning, and remembering help shape process.” In summary, the context element refers to the surrounding environment that serves as the catalyst for the strategy, the content element concerns the substance of a strategy an organization intends to apply, and the process element relates to the issue of how the selected strategy can be introduced, implemented, and managed.

The Framework

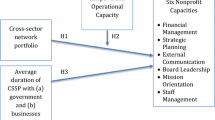

For each of the three overarching elements of strategy, we identify factors that are relevant to NPOs embarking upon a strategy for NBC, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The fundamental aim of this strategy is to allow NPOs to improve the scale of their collaboration with the business sector both quantitatively, by increasing the number of business partners in the portfolio, and qualitatively, through better partners and agreements. The figure also indicates that NPOs’ size and mission impact upon the factors within each of the three elements.

The Context of an NBC Strategy

The context element concerns external and internal factors that may facilitate or inhibit the adoption of an NBC strategy. We identified four factors to address in this element: “NBC purpose,” “stakeholder expectation,” “nonprofit competition,” and “cultural barrier.”

NBC Purpose

As mentioned earlier, NPOs are facing difficult circumstances that affect their sustainability, hence evoking the need to consider new options such as the collaboration with the business sector. NPOs might seek NBC for different purposes such as diversification of income streams, enhancement of publicity, and brand improvement, or absorption of business-related skills (Elkington and Fennell 2000; den Hond et al. 2012), all of which arguably underlie one goal: to enhance sustainability. Although these purposes might be seen as doable concomitantly, we contend that a better NBC strategy would be developed if the purpose of an NBC were highly focused. Support for this argument is twofold. First, a clear and specified purpose would provide a clear direction and basis for making consistent choices and setting compatible activities to formulate a more robust strategy (Thompson and Martin 2010, p. 266). Moreover, it is likely that the targeted purpose would influence the strategy content and process. For example, when an NBC is sought only for income purposes (i.e., as a means to achieve monetary gains), NPOs might be less discriminating in regard to prospective business partners, as long as that NBC does not conflict with their mission or values. By contrast, being driven by the purpose of building a reputation or access to business knowledge, which should support sustainability in the long term, NPOs are likely to be selective in terms of with whom to collaborate and how. For example, CARE (an NPO) has increased its visibility and brand awareness following a collaboration with Starbucks, which promoted the collaboration through all of its globally located branches (Austin 2000a, p. 31). Similarly, the Edna McConnell Clark foundation (an NPO that has operational experience in developing countries) collaborated with Pfizer (a pharmaceutical company that developed a cost-effective treatment for trachoma “eye disease”) to coordinate the prescription and distribution processes of this medicine to communities where the NPO operates (see Hohler 2007). Subsequently, the volume of work expanded to engage the British government, which targeted 30 million people worldwide for treatment (Porter and Kramer 2002). Such an opportunity enabled this NPO to build its capacity and become a global organization. Second, a focused purpose should promote stakeholder support for an NBC strategy. A clearly specified purpose is likely to aid appreciation of the requirements, timescales, and outcomes of any proposed collaboration and thus to enable stakeholders to gauge the collaboration’s potential effectiveness (Behn 2003).

Proposition 1

NPOs that define a specific purpose to underpin their NBC strategy will develop a more successful strategy.

Stakeholder Expectations

When designing and implementing new initiatives, NPOs need to carefully consider their heterogeneous stakeholder groups (e.g., donors, media, and general public) to maintain their social legitimacy (Dacin et al. 2007). This requirement, however, is complex because it comprises two overlapping issues. First, NPO stakeholders are normally sensitive to any incongruence that may arise when activities are perceived to contradict with what has been formally stated (Tschirhart 1996). Second, stakeholders often possess diverse expectations (Conroy 2005) that relate to the fact that NPOs are subject to various types of accountability, such as legal and professional accountabilities, and the obligation to add value (Hoefer 2000; Kearns 1996).

Applied to NBC, not all stakeholders would be expected to support the initiative (Westley and Vredenburg 1991). Stakeholders expect and demand NPOs to be effective (Kong 2008; Herman and Renz 2008) and at the same time investigate new opportunities to enhance their sustainability to pursue their mission. Nonetheless, stakeholders are likely to be concerned about collaborating with a business due to “mission creep,” which describes the situation where a gradual mission or goal deviation takes place influenced by, for instance, the interests of the business partner (cf. Akingbola 2012; Peterson 2010). For example, the American Medical Association (AMA) entered into a sponsorship agreement with a business that included putting the AMA logo exclusively on the products of the business in return of predefined royalties. Many AMA stakeholders opposed this step after it was announced because they perceived the agreement that endorsed the promotion of medical products without proper testing to be misaligned with AMA’s original mission (Press 1998).

Proposition 2

NPOs that are aware of the complexity of stakeholder expectations will develop a more acceptable NBC strategy.

Nonprofit Competition

Competition is a central part of any external context of organizations that produce similar products or provide similar services (Johnson et al. 2011, p. 49). The nonprofit sector has been transformed during the past twenty years wherein competition has become more intense (Phillips 2012). Under such conditions, the financial sustainability of NPOs has become a critical concern because these organizations, which are also increasing in number (Inaba 2011; Keller et al. 2010), are competing for fixed or even deteriorating traditional funding sources. Similarly, NPOs that pursue a similar mission are competing for limited collaboration opportunities. Due to the current economic climate, businesses are becoming more focused when selecting their nonprofit partners to create better social and economic returns from their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) investments (Godfrey 2005; Porter and Kramer 2002). NPOs need to recognize this competition and understand their own strengths and weaknesses in comparison to similar NPOs. NPOs also need to investigate how to become different and more appealing to prospective business partners (as discussed below under the “strategic position” factor). For example, we expect that NPOs that are able to undertake social initiatives effectively or that are able to fulfill the various needs of businesses will be distinct in comparison to competitors and thus more successful in securing a greater collaboration quota of this competitive market. As a director at Save the Children (an international NPO) explains, “Corporate profits have been suffering; corporate and social responsibility budgets have been cut. There is a smaller pie out there so you have to have a really compelling proposition if you want to take a slice of it” (Cave 2011).

Proposition 3

NPOs that consider the characteristics of their competitors to differentiate themselves will develop a more successful NBC strategy.

Cultural Barrier

Because of changes in the economic environment (as discussed above), NPOs are under increasing pressure to adopt new and business-like approaches to increase their efficiency and effectiveness (Baur and Schmitz 2011; Helmig et al. 2004). These approaches might include the adoption of marketing and branding techniques (Kotler and Andreasen 1996), using the concepts of competitive advantage and positioning strategies (Wicker and Breuer 2012), and modernization of the services NPOs provide (Weerawardena et al. 2010). Nonetheless, research indicates that NPOs often develop a cultural barrier in adopting such approaches, despite their significance for organizational sustainability. As Lindenberg (2001, p. 248) explains, “They [NPOs] fear that too much attention to market dynamics and private and public sector techniques will destroy their value-based organizational culture.” We contend, therefore, that collaborating with businesses—as one of these new approaches—might be perceived by staff and volunteers as a step-change in values. This change might generate a culture of internal resistance (i.e., a cultural barrier) because collaboration might be considered as endangering the traditional image of the NPO (Mannell 2010; Wilson et al. 2010). This negative attitude might evolve from the assumption of incompatibility between the NPO’s values and culture (often characterized as socially driven, participative, and co-operative) and the values and culture of the business (often described as profit driven, hierarchical, and competitive) (Berger et al. 2004; Parker and Selsky 2004).

Proposition 4

NPOs that are aware of the potential causes of a cultural barrier will develop a more internally acceptable NBC strategy.

The Content of an NBC Strategy

In general, strategy content concerns the deliberate choices that an organization adopts in endeavoring to achieve pre-determined objectives (Hoffer 1975; Jemison 1981). We suggest that two factors are significant within this element: “collaboration level” and “strategic position.”

Collaboration Level

Several forms of NBC are defined and discussed within the cross-sector collaboration literature. Austin (2000b) suggests that these various forms can be viewed as a continuum comprising three distinctive levels. “Philanthropic” (e.g., corporate giving) involves an NPO and business collaboration with minimal institutional involvement and resource exchange. “Transactional” refers to a mutual exchange of resources (e.g., sponsoring), where a business provides specific resources to an NPO in return for publicity and direct sales increases (Liston-Heyes and Liu 2010). The highest level, “integrative” (e.g., strategic partnership), represents the utmost frontier of an NBC because both partners begin to merge their activities and missions toward more collective actions and organizational integration.

This factor, we contend, is fundamental to the content of an NBC strategy because it explains the depth of collaboration and the degree to which each organization is willing to engage (Wymer and Samu 2003). For instance, the targets of an NPO when entering into a sponsorship collaboration (transactional level) will not extend beyond obtaining financial resources and/or increased visibility. In connection with a strategic alliance (integrative level), however, an NPO may aim to change its business partner’s behavior (Yaziji and Doh 2009). In addition, each of these levels has different consequences for the internal and external context of the NPO (Keys et al. 2009). For example, a higher collaboration level would require greater staff and volunteer commitment and a better cultural fit between the two partnering organizations and incur higher public expectations and scrutiny (Austin 2000b; Hudson 2005). Similarly, different risks are associated with different NBC levels. For instance, cause-related marketing would put the NPO in a resource-dependent position, which might weaken its ability to challenge business behavior; thus, the NPO might become vulnerable to co-optation by its business partner (Baur and Schmitz 2011).

However, this factor should not be considered in isolation from other factors. For example, “stakeholder expectations” (context element) has a considerable influence on selecting the collaboration level, where some collaboration levels might be more acceptable to the stakeholders than others. Simpson et al. (2011) found that the extent of compatibility between the collaboration and stakeholder expectations influenced the governance of the relationship. For example, stakeholders with high expectations (e.g., those who have a strong ideology) preferred a low collaboration level (i.e., informal governance mechanism) to keep their NPO distant from the business partner. Moreover, an NPO might adjust the level of collaboration to satisfy its stakeholders (Oliver 1991; Hess and Warren 2008). A lower level of collaboration normally includes less commitment and engagement by the NPO, thereby mitigating the potential risk of being linked to the business (Baur and Schmitz 2011). Accordingly, this lower level of collaboration should alleviate the effect of a cultural barrier because a higher level of collaboration would typically require greater staff involvement (Austin 2000a). In regard to the strategy process, smaller NPOs, which typically have a restricted budget for administration costs (including transaction costs as discussed in the process element), are likely to focus more on a lower collaboration level because it delivers more tangible results that require less staff commitment and cost.

Proposition 5

NPOs that realize the consequences (e.g., resources required, commitment and risks) of each NBC level will develop a more successful NBC strategy.

Strategic Position

The strategic position (SP) is a mechanism by which an organization can be distinguished from other similar organizations (Porter 1996) and which plays a key role in maintaining an organization’s competitiveness in the marketplace (Kotler and Andreasen 1996). For NPOs, the SP is typically built upon the NPOs’ values and capacities to fulfill their mission (Chetkovich and Frumkin 2003) and is more influential in securing a stronger market position than relying merely on the efficiency of operations (Chew and Osborne 2009a). The SP also contributes to how the public perceives the NPO, which can influence the magnitude of public support (Frumkin and Kim 2001). As a factor of the content element of an NBC strategy, the SP should enable NPOs to create a distinctive and attractive position in the eyes of prospective business partners (Kotler and Andreasen 1996) that stems from the NPOs’ ability to achieve both social and economic gains for the business (Porter and Kramer 2002). Planning for an NBC strategy should include publicizing the capabilities (e.g., specialized knowledge of issues that relate to social concerns) that businesses lack and value. Moreover, NPOs enjoy legitimacy in the eye of society and have dense networks of stakeholders that businesses can access, such as donors, regulators, and public lobbyists (Yaziji 2004). Businesses might also be interested in other benefits such as the geographic location in which the NPO operates. If the NPO is geographically spread, a business can tap into this advantage to increase its reach and hence better engage with the communities at the grassroots level. Businesses might also be interested in a well-established and widely recognized NPO brand, such as in the case of cause-related marketing (transactional collaboration). Such features would put an NPO in an appealing position in regard to maximizing the return that businesses can achieve from their social investments (Cantrell et al. 2008).

Furthermore, we claim that the SP plays a substantial role in the competition between NPOs. Given the intense competitive environment in which NPOs currently operate, NPOs need to emphasize their unique attributes compared to other NPOs to establish a distinct position (Maple 2003).

Preposition 6

NPOs that recognize and market their unique capabilities will be more attractive to prospective business partners.

The Process of an NBC Strategy

The strategy process typically concerns activities that support the implementation of the decision-making (i.e., strategy content) outputs (Huff and Reger 1987). We draw on the work of Ketchen et al. (1996) and others to suggest three factors as being fundamental to the NBC strategy process: “power imbalance,” “communication channels,” and “transaction costs.” Before proceeding, it should be noted that the focus of the process element in this paper is concerned with the formulation and implementation of an NBC strategy and not the execution of the collaboration itself.

Power Imbalance

For any cross-sector collaboration, power imbalance is a potential concern (Baur and Schmitz 2011; Martínez 2003). The term power can be defined as “the potential to influence others’ action” (Emerson 1976, p. 354). In addition, it is evident that power issues can be exaggerated in situations where organizational self-interests and the collective goals of the collaboration are not congruent (Das and Teng 2001). Power imbalance between partners can result from a situation where one party is perceived to be in a stronger position than the other (Mutch 2011), which is typically caused by a perceived unequal flow of benefits between the partners (e.g., control of resources by one partner) (Baur and Schmitz 2011). However, another cause of power imbalance is a situation in which one partner is structurally stronger, such as the collaboration between a multinational corporation and an NPO (cf. Huxham and Vangen 2005, p. 162). We also contend that imbalance might be influenced by the collaboration level. For instance, the power of NPOs in low-level collaborations (e.g., sponsoring) may be weaker than in high-level collaborations such as strategic partnerships (Baur and Schmitz 2011) because the business might appreciate the value of the nonprofit partner to a lesser extent (Tracey et al. 2005). These various causes might explain why NPOs are traditionally perceived as the partners with less power in cross-sector collaboration (Goerke 2003; Martinez 2003).

Parker and Selsky (2004, p. 467) refer to the impact of the imbalance as “problematic,” leading to instability of the relationship. Imbalance can limit the potential of the collaboration because the skills and resources of the weaker party might not be fully recognized and hence be poorly utilized (Berger et al. 2004). By considering this issue early when devising an NBC strategy, NPOs can anticipate the likelihood of such imbalance (Bryson et al. 2006). Emphasizing, for instance, their trusted brand and nested social networks (Berger et al. 2004) should help NPOs to avoid being the weaker partner in prospective collaborations.

Proposition 7

NPOs that recognize the issue of power imbalance and proactively employ their capabilities to avoid the traditional imbalance situation will develop a more successful NBC strategy.

Communication Channels

Communicating the strategy of collaboration and its consequences will help NPOs to manage the expectations of their stakeholders (Andre et al. 2008). Early communication of the expected value or return from an NBC should help to generate stakeholder support (Austin 2000b). Furthermore, communicating any potential risks from the collaboration and how these risks might be addressed is likely to be perceived positively by stakeholders. Communicating an NBC in this way should help to demonstrate that the strategy of an NBC is well conceived.

We refer to communication channels as a two-way (inbound and outbound) means of sending and receiving information regarding an NBC strategy between an NPO and its stakeholders. The outbound channel (OC) relates to information about the collaboration that an NPO provides to its stakeholders (e.g., staff and volunteers, supporters and the general public). If NPOs communicate the potential benefits from the collaboration to their stakeholders, the NPOs are likely to mitigate the negative impact of possible resistance or conflict (i.e., “cultural barrier” factor). At the same time, NPOs require an inbound channel (IC), which involves information an NPO seeks to collect from different stakeholder groups. Clarke and Fuller (2011) examined the role of information channels that were designed to provide feedback about the formulation and implementation of a collective strategy for cross-sector social partnerships. The authors found that these channels were fundamental in responding to internal and/or external demands, which later were translated into strategy changes. Through such channels, useful information can be gathered to avoid possible sources of conflict and to provide decision-makers with real-time data necessary to insure that the process is progressing smoothly (Gates 2010). For instance, because they are likely to have detailed knowledge about what might work and what not, junior staff and volunteers might perceive unforeseen risks that contradict the positive view of senior decision-makers. By adopting an IC, the NBC strategy can be improved continuously while being implemented.

In addition, we contend that the collaboration level (content factor) would influence the nature of the communication channels. For instance, when planning to target a high-level collaboration (e.g., joint venture), communication with multiple stakeholders would become more complex than that of a low-level collaboration (e.g., philanthropic). Typically, this complexity occurs because a high-level collaboration requires more engagement and interaction between a business and the NPO (Austin 2000b) and hence will inevitably require the involvement of more stakeholder groups.

Preposition 8

NPOs that employ real-time, two-way communication channels will develop a more successful NBC strategy.

Transaction Costs

Within the domain of inter-organizational collaborations, transaction costs are generated from three main sources: (1) the cost of finding partners, (2) the cost of negotiating agreements with these partners, and (3) the cost of monitoring and enforcing compliance with the agreement (Macher and Richman 2008). In cross-sector collaborations, it is more likely that positive change will take place if both partners are able to overcome or at least lessen these costs (King 2007). For NPOs, the cost of fundraising, which in general includes transaction costs, is a sensitive issue (Sargeant and Kähler 1999). NPOs are under constant pressure by donors to minimize such costs to the lowest possible level (Andreoni and Payne 2011) and to insure that any expenditure is carefully monitored such that the public receives optimal value from their contributions. Nonetheless, as part of an NBC strategy process, NPOs need to allocate specific resources to thorough research to understand the various interests of the business sector and to communicate with potential partners. Resources are also required to establish communication channels with relevant individuals and groups.

Therefore, although reducing administration costs represents good practice, doing so should not be sought as an end in itself when planning for an NBC because minimizing these costs is not always correlated with being viewed as effective by society (Frumkin and Kim 2001); however, value for money is becoming more important when assessing the effectiveness of NPOs (Young and Steinberg 1995). In essence, the focus should be on optimizing transaction costs by managing these costs as an investment in research and rational forecasting rather than as administrative costs that should be reduced. Through this mind-set, NPOs should be better able to gain the trust of their stakeholders by disseminating a potential course of action based on acquired information or informed choice.

Proposition 9

NPOs that manage transaction costs as an initial investment rather than as administrative costs will be able to develop a more successful NBC strategy.

The Influencing Factors

As depicted in Fig. 1, we suggest that the three elements of an NBC strategy will be influenced by two factors: NPO size and mission.

NPO Size

Several scholars have called for the consideration of the type of NPO when researching the nature of NPOs to understand behavioral differences and similarities across organizations that constitute the nonprofit sector (Herman and Renz 2008; Vakil 1997). However, classifying these organizations is still a matter of debate. For instance, Vakil (1997) suggests two attributes for categorizing NPOs. The “essential” attribute concerns the orientation of an organization, such as providing a service, and the “contingent” attribute relates to the sector in which the organization operates, for example, education or health sectors. The World-Bank (2010) also adopts two functional dimensions to categorize NPOs: “operational,” or NPOs that provide services, and “advocacy,” or NPOs with a concern for reforming social or political systems. Similarly, Yaziji and Doh (2009) suggest two categorization dimensions: “beneficiary” (self-members vs. others), and “type of activity” (service vs. advocacy).

Given the lack of agreement and supporting evidence on NPO typologies, we select size in terms of annual income to illustrate the potential impact of NPO type on the factors of strategy development. We expect that this influencing factor will be important because it relates to other issues, including complexity of the organizational structure, accessibility to resources, and publicity, which are relevant to the development of any NBC. Many context factors (element 1) can be influenced by the size of an NPO. Reflecting coercive forces within institutional theory (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), larger organizations are more likely to confront greater stakeholder expectations than smaller organizations. Furthermore, larger organizations typically receive more attention from the media and society due to their greater visibility and expected impact on society (Goodstein 1994). Therefore, larger organizations are likely to be carefully monitored by the public when engaging in an NBC because NPOs represent “trusted” organizations that defend the public’s interest (Yaziji and Doh 2009). The purpose of an NBC is also relevant here. In pursuing their sustainability, larger NPOs are more likely to target NBCs that concern the development of their organizational capacity (e.g., marketing and strategic planning) than generate income, which they can secure from other sources (e.g., the public). In contrast, smaller NPOs are more likely to focus on gaining financial resources that fulfill their immediate needs. Similar to contextual aspects, the size of an NPO is likely to influence content factors (element 2). For instance, large international NPOs are typically interested in collaborations at higher levels, such as strategic partnering, rather than simply engaging in business sponsoring, which might be the target for smaller NPOs. High-level collaborations can grant NPOs more control over the relationship and enable them to plan for long-term objectives (Wymer and Samu 2003) and create greater social impact (Porter and Kramer 2002). Finally, the size of an NPO is likely to influence the process factors (element 3). The size of NPOs, for instance, might affect transaction costs associated with the process of an NBC strategy. Larger NPOs are likely to incur higher transaction costs while formulating and implementing their strategy because of the bureaucracy and complexity of their operations (McClusky 2002). These costs, however, might become an issue because larger NPOs are highly visible to the public and therefore subject to close and continuous scrutiny (Conroy 2005). In contrast, smaller NPOs might consider these costs (although not relatively high) a burden that cannot be justified within their constrained budgets.

NPO Mission

The mission of NPOs is crucial with regard to the social justification of their existence (Bryman 1988). Moreover, the mission “defines the value that the organization intends to produce for its stakeholders and for society” (Moore 2000, p. 190). NPOs are normally described as organizations driven by a mission, from which their strategic objectives are derived (Kaplan 2001). In addition, the mission is an instrumental tool for an NPO and its stakeholders to systematically assess the effectiveness of any adopted strategy (Sawhill and Williamson 2001). We seek to demonstrate the impact of a mission on an NBC strategy by considering the influence of a mission on the factors included in the three elements of strategy.

With regard to context factors, a mission that is well articulated and appreciated by society is expected to enhance stakeholder trust (Frumkin and Andre-Clark 2000). In turn, stakeholders might become more accepting of an NBC because they are in a position to discern any mission drift that may occur over time. The NPO mission, in addition to the effect of the NPO size, might influence the level of collaboration (content factor). For instance, ecology-centric NPOs, which aim to alter the decision-making and preference formation of businesses (Doh and Guay 2006), are typically less likely to engage with the business sector via sponsorships in comparison to social-centric NPOs. This lower level of collaboration would put ecology-centric NPOs in a vulnerable position because they have less power and control over the agreement (Arenas et al. 2009). Finally, the NPO mission has the potential to affect the process factors. For instance, Thomson and Perry (2006) argue that an organization’s mission can become an obstacle in the collaboration process. More specifically, partners are often keen to distance the mission of their own organization (as a distinct identity) from the collaboration mission (as a collective objective). This distinction can create tension between organizations’ self-interests to achieve their respective missions and the collective interest to achieve collaboration objectives (Tschirhart et al. 2005).

Discussion

In this paper, we present a new framework to facilitate NBC from the NPO perspective. We shift the focus from how NBC can deliver value to both society and business to address the interests of nonprofits. Research indicates that through NBC, NPOs can obtain various tangible and intangible benefits that foster their organizational sustainability (Peloza and Falkenberg 2009; Simpson et al. 2011). The framework describes factors that are important to consider when developing a collaboration strategy to attract prospective business partners; that is, we aim to help NPOs become proactive in NBC rather than being reactive to what businesses might offer.

We believe that the framework is timely on account of three reasons. First, and because of the growing complexity of challenges facing society, it is realized that no single sector (i.e., government, business, and NPO) can effectively manage these challenges alone (Googins and Rochlin 2000; Struyk 2002). This fact highlights the need to explore new ways that would improve collaboration between these sectors to deliver superior value. Being strategic, as suggested in this paper, should facilitate the achievement of a good fit between an NPO and a business. By developing a strategy, NPOs should better understand the purpose of collaboration, appreciate their unique attributes, and also recognize the risks involved in NBC. Such awareness should promote internal consistency (i.e., if the collaboration fits with staff, supporters, volunteers, and organizational resources) and external consistency (i.e., if the collaboration fits with business partners’ demands and objectives), thereby reducing the possibility of collaboration failure. Second, NPOs constantly seek to diversify their funding sources and to leverage their capacity, not only to become sustainable but also to become more effective in achieving their goals. By considering NBC from a strategic perspective, NPOs are expected to improve the scale of their collaborations both quantitatively and qualitatively. Third, there is mounting pressure on businesses to change their CSR approaches from traditional practices (e.g., corporate giving) to new forms of engaging with society, such as NBC (Austin, 2000). NBC enables businesses to deepen their understanding of social problems and thus become capable of assisting in the development of better solutions (Barkay 2011; McDonald and Young 2012). This change represents an opportunity for NPOs to place themselves in an attractive position for the business sector.

However, collaborations should not be considered a risk-free strategy because they bring NPOs risks and challenges (e.g., Andreasen 1996; Ashman 2001; Austin 2000b; Babiak and Thibault 2009), which we discuss under three themes: collaboration failure, collaboration cost, and damage of image. First, collaboration failure occurs when partners fail to reach the planned outcomes, which would be detrimental to all (Le Ber and Branzei 2010). A lack of fit between partners’ values, attributes, and objectives is often described as the main reason for collaboration failure (Bryson et al. 2006; Rondinelli and London 2003). However, attaining a good organizational fit is not an easy task (Austin 2000a, p. 61) given the “inherited distrust” (Rondinelli and London 2003, p. 63) and heterogeneity between the nonprofit and business sectors. Berger et al. (2004) identify nine dimensions (mission, resources, management, work force, target market, cause, cultural, cycle, and evaluation) that underpin NBC fit. The more compatible the partners are across these dimensions, the more likely they will achieve a successful collaboration. Furthermore, failure of a particular collaboration would raise questions regarding the NPO’s accountability and efficiency. For example, when the American Medical Association (AMA) canceled the sponsoring agreement with Sunbeam Corporation as a result of perceived mission misalignment, the cost to the AMA was $9.9 m (Press 1998). Such incidents might jeopardize future NBC opportunities due to a lack of support from stakeholders. Second, there is a potential risk that the cost of establishing a collaboration (i.e., transaction costs) might outweigh the desired outcomes (Ashman 2001). This risk is a critical issue because the NPO might lose credibility and be considered inefficient due to wasting resources (e.g., donations and funds). As previously discussed, stakeholders maintain high expectations of their NPO’s ability to demonstrate accountability (Babiak and Thibault 2009) and efficiency in how resources are used. Third, the image of an NPO represents its most precious asset, which reflects its values and mission. Moreover, image plays a key role in gaining competitive advantage, as discussed under the “strategic position” factor. However, NPOs should be careful when planning for an NBC. Porter and Kramer (2011, p. 64) comment that “In recent years, business increasingly has been viewed as a major cause of social, environmental, and economic problems. Companies are widely perceived to be prospering at the expense of the broader community.” This perspective reflects a traditional antagonistic attitude that views NPOs as “sleeping with the enemy” when involved in an NBC (Rondinelli and London 2003, p. 63). Furthermore, an NPO’s image can be tarnished should its business partner’s reputation deteriorate as a result of social or environmental misconduct. Such harm to the image might result in a loss of legitimacy and, in turn, the withdrawal of community support (Andreasen 1996; Dunn 2010).

There are several factors, however, that might alter the severity of these risk causes. The level of collaboration moderates the extent to which NPOs are accountable for business misconduct because the level of collaboration determines the nature of the relationship between the partners and the depth of the NPOs’ involvement (Austin 2000b). In addition, the reaction of stakeholders often varies according to the NPO mission. For instance, stakeholders of environment-centric NPOs are typically more sensitive toward NBC than stakeholders of social-centric NPOs (as illustrated under “NPO mission”). In conclusion, we contend that the framework should help NPOs to better appreciate the risks associated with potential collaborations such that risks are neither under- nor overestimated.

Implications for Research and Practice

Our purpose is to advance theories on NBC by offering a framework for understanding collaboration as a strategic issue from the NPO perspective. The framework is based on the three elements of strategy as rooted in the strategic management and change literature. However, our framework requires scrutiny, and we next identify areas for potential future research.

First, there is a need to conduct studies to compare NPOs that have developed successful collaborations with NPOs that have been unsuccessful. This line of inquiry would allow examining the validity of the propositions. Second, our framework suggests that the factors are of equal importance for the development of an NBC strategy. Nevertheless, such equality might not be the case in reality; some factors might be more important than others. For example, the issue of managing the imbalance of power with business partners might be more significant than transaction costs in determining successful outcomes. This type of analysis would not only deepen the understanding of the relative importance of the factors but also enable NPOs to optimize their limited human and capital resources (Bryson 2010) by addressing the most important factors. Third, we suggest that the type of NPO can influence an NBC strategy. However, in this paper, we only discuss the impact of size (i.e., small vs. large NPOs). Other classifying dimensions, such as centrally controlled (head office control over regional offices) vs. autonomous (independent regional offices) NPOs (Berger et al. 2004), service vs. advocacy NPOs (Yaziji and Doh 2009, p. 5), and local vs. international NPOs, would be worth evaluating. Such comparisons would enrich our understanding by proving insights into the impact of the form and structure of an NPO on NBC strategy development. Finally, our framework has been designed on the premise that an NBC strategy would be developed by a single NPO. However, it is our expectation that the framework can also assist a group of NPOs or intra-sector alliances to collectively develop an NBC strategy. For instance, it would be worthwhile to investigate whether such alliances would strengthen the “strategic position” of the allied NPOs when approaching businesses: the alliance might gain greater attention from businesses due to the pooled resources and capabilities of the NPOs (Foster and Meinhard 2002). However, the alliance might create challenges with regard to the coordination of efforts/resources to harmonize the relationships between the NPOs and to minimize the potential of free-riders (Peloza and Falkenberg 2009).

In regard to practice, the framework can be used as a guide to help managers in the nonprofit sector to develop a strategy for NBC. Thus, the framework can be used as a checklist to help decision-makers predict and preempt problems and risks normally associated with NBCs. The framework should encourage NPOs to move beyond traditional thinking and become more open and less skeptical when considering the issue of collaboration (Andreasen 1996). Importantly, the framework proposes that managers should identify and publicize their NPO’s distinctive capabilities, such as being strongly legitimized by society and possessing social and environmental expertise to address the concerns of society. Emphasizing these capabilities should help to place NPOs on a more equal level vis-à-vis their business partners. By realizing their distinctive strengths, NPOs are expected to become stronger when entering collaborations and hence create more value not only to support their beneficiaries but also to enhance their long-term sustainability.

Notes

Drawing on the work of Courtney (2002, pp. 37–40), Hudson (2002, p. 9), and Osborne (1996, p. 11), we consider nonprofit organizations to be organizations that are formally structured, operate exclusively for a not-for-profit purpose, are independent of the government, and utilize any financial surplus to improve the services they provide or to develop internally. Furthermore, we use the terms “NPOs” and “nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)” interchangeably (Selsky and Parker 2005).

References

Akingbola, K. (2012). A model of strategic nonprofit human resource management. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–27. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9286-9

Andre, N., Theo De, B., & Hakan, H. (2008). Partnerships for corporate social responsibility. Management Decision, 46, 152.

Andreasen, A. R. (1996). Profits for nonprofits: Find a corporate partner. Harvard Business Review, 74, 47–59.

Andreoni, J., & Payne, A. A. (2011). Is crowding out due entirely to fundraising? Evidence from a panel of charities. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 334–343.

Arenas, D., Lozano, J., & Albareda, L. (2009). The role of NGOs in CSR: Mutual perceptions among stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 175–197.

Ashman, D. (2001). Civil society collaboration with business: Bringing empowerment back in. World Development, 29, 1097–1113.

Austin, J. (2000a). The collaboration challenge. How nonprofits and businesses succeed through strategic alliances. San Francisco: Jossy-Bass Publishers.

Austin, J. (2000b). Strategic collaboration between nonprofits and business. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 69–97.

Babiak, K., & Thibault, L. (2009). Challenges in multiple cross-sector partnerships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 117–143.

Barkay, T. (2011). When business & community meet: A case study of Coca-Cola. Critical Sociology. doi:10.1177/0896920511423112.

Baur, D., & Schmitz, H. (2011). Corporations and NGOs: When accountability leads to co-optation. Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 9–21.

Behn, R. D. (2003). Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review, 63, 586–606.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2004). Social alliances: Company/nonprofit collaboration. California Management Review, 47, 58.

Bies, R. J., Bartunek, J. M., Fort, T. L., & Zald, M. N. (2007). Corporations as social change agents: Individual, interpersonal, institutional, and environmental dynamics. Academy of Management Review, 32, 788–793.

Bingham, T., & Walters, G. (2012). Financial sustainability within UK charities: Community sport trusts and corporate social responsibility partnerships. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–24. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9275-z

Bryman, A. (1988). Quantitative and qualitative in social research. London: Unwin Hyman.

Bryson, J. M. (2010). The future of public and nonprofit strategic planning in the United States. Public Administration Review, 70, s255–s267.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66, 44–55.

Cantrell, J., Kyriazis, E., Noble, G., & Algie, J. (2008). Towards NPOs deeper understanding of the corporate giving manager’s role in meeting salient stakeholders needs. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 20, 191–212.

Cave, A. (2011). Save the children’s Douglas Campbell rouse: The government must incentivise philanthropy. 20 Feb 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financetopics/profiles/8334930/Save-the-Childrens-Douglas-Campbell-Rouse-The-Government-must-incentivise-philanthropy.html.

Chetkovich, C., & Frumkin, P. (2003). Balancing margin and mission: Nonprofit competition in charitable versus fee-based programs. Administration Society, 35, 564–596.

Chew, C., & Osborne, S. P. (2009a). Exploring strategic positioning in the UK charitable sector: Emerging evidence from charitable organizations that provide public services. British Journal of Management, 20, 90–105.

Chew, C., & Osborne, S. P. (2009b). Identifying the factors that influence positioning strategy in U.K. charitable organizations that provide public services. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 29–50.

Clarke, A., & Fuller, M. (2011). Collaborative strategic management: Strategy formulation and implementation by multi-organizational cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 85–101.

Conroy, D. K. (2005). Non-profit organisations and accountability: A comment on the Mulgan and Sinclair frameworks. Third Sector Review, 11, 103–116.

Courtney, R. (2002). Strategic management for voluntary non-profit organizations. UK: Routledge.

Dacin, M. T., Oliver, C., & Roy, J.-P. (2007). The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 169–187.

Dahan, N. M., Doh, J. P., Oetzel, J., & Yaziji, M. (2009). Corporate-NGO collaboration: Co-creating new business models for developing markets. Long Range Planning, 43, 326–342.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B.-S. (2001). Trust, control, and risk in strategic alliances: An integrated framework. Organization Studies, 22, 251–283.

Den Hond, F., De Bakker, F. G. A., & Doh, J. (2012). What prompts companies to collaboration with NGOs? Recent evidence from the Netherlands. Business & Society. doi:10.1177/0007650312439549.

Dimaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 14.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 47–73.

Dunn, P. (2010). Strategic responses by a nonprofit when a donor becomes tainted. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0899764008326770.

Elkington, J., & Fennell, A. (2000). Partners for sustainbility. In J. Bendell (Ed.), Terms for endearment: Business, NGOs and sustainable development. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

Foster, M. K., & Meinhard, A. G. (2002). A regression model explaining predisposition to collaborate. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31, 549–564.

Frumkin, P., & Andre-Clark, A. (2000). When missions, markets, and politics collide: Values and strategy in the nonprofit human services. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 141–163.

Frumkin, P., & Kim, M. T. (2001). Strategic positioning and the financing of nonprofit organizations: Is efficiency rewarded in the contributions marketplace? Public Administration Review, 61, 266–275.

Gates, M. F. (2010). What nonprofits can learn from Coca-Cola. http://www.ted.com/talks/melinda_french_gates_what_nonprofits_can_learn_from_coca_cola.html, Accessed Nov. 2010

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 30, 777–798.

Goerke, J. (2003). Taking the quantum leap: Nonprofits are now in business. An Australian perspective. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8, 317–324.

Goodstein, J. D. (1994). Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. The Academy of Management Journal, 37, 350–382.

Googins, B. K., & Rochlin, S. A. (2000). Creating the partnership society: Understanding the rhetoric and reality of cross-sectoral partnerships. Business and Society Review, 105, 127–144.

Guo, C., & Acar, M. (2005). Understanding collaboration among nonprofit organizations: Combining resource dependency, institutional, and network perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34, 340–361.

Harris, M. E. (2012). Nonprofits and business: Toward a subfield of nonprofit studies. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0899764012450777

Helmig, B., Jegers, M., & Lapsley, I. (2004). Challenges in managing nonprofit organizations: A research overview. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 15, 101–116.

Herman, R. D., & Renz, D. O. (2008). Advancing nonprofit organizational effectiveness research and theory: Nine theses. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 18, 399–415.

Hess, D., & Warren, D. E. (2008). The meaning and meaningfulness of corporate social initiatives. Business and Society Review, 113, 163–197.

Hoefer, R. (2000). Accountability in action?: Program evaluation in nonprofit human service agencies. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11, 167–177.

Hoffer, C. W. (1975). Toward a contingency theory of business strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 18, 784–810.

Hohler, S. (2007). The tropical disease program: Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, 1974. Center for Strategic Philanthropy and Civil Society (Duke). http://cspcs.sanford.duke.edu/content/tropical-disease-program-edna-mcconnell-clark-foundation-1974, January, 2013.

Holmes, S., & Smart, P. (2009). Exploring open innovation practice in firm-nonprofit engagements: A corporate social responsibility perspective. R & D Management, 39, 394.

Hudson, M. (2002). Managing without profit: The art of managing third-sector organizations. London: Directory of Social Change.

Hudson, M. (2005). Managing at the leading edge- new challenges in managing nonprofit organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Huff, A. S., & Reger, R. K. (1987). A review of strategic process research. Journal of Management, 13, 211–236.

Huxham, C., & Vangen, S. (2005). Managing to collaborate: The theory and practice of collaborative advantage. New York: Routledge.

Inaba, M. (2011). Increasing poverty in Japan: Social policy and public assistance program. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 5, 79–91.

Jemison, D. B. (1981). The importance of an integrative approach to strategic management research. Academy of Management Review, 6, 601–608.

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., & Scholes, K. (2011). Exploring strategy. London: Prentice Hall.

Kaplan, R. S. (2001). Strategic performance measurement and management in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11, 353–370.

Kearns, K. P. (1996). Managing for accountability. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Keller, E. W., Dato-On, M. C., & Shaw, D. (2010). NPO branding: Preliminary lessons from major players. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 15, 105–121.

Ketchen, D., Thomas, J., & McDaniel, R. (1996). Process, content and context: Synergistic effects on organizational performance. Journal of Management, 22, 231–257.

Keys, T., Malnight, T., & Graaf, K. (2009). Making the most of corporate social responsibility. McKinsey Quarterly. doi:10.1108/14720701111159280

King, A. (2007). Cooperation between corporations and environmental groups: A transaction cost perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 32, 889.

Kong, E. (2008). The development of strategic management in the non-profit context: Intellectual capital in social service non-profit organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10, 281–299.

Koschmann, M. A., Kuhn, T. R., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2012). A communicative framework of value in cross-sector partnerships. Academy of Management Review, 37, 332–354.

Kotler, P., & Andreasen, A. (1996). Strategic marketing for nonprofit organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kourula, A. (2009). Corporate engagement with non-governmental organizations in different institutional contexts—a case study of a forest products company. Journal of World Business, 45(4), 395–404

le Ber, M. J., & Branzei, O. (2010). (Re)forming strategic cross-sector partnerships relational processes of social innovation. Business & Society, 49, 140–172.

Lindenberg, M. (2001). Are we at the cutting edge or the blunt edge?: Improving NGO organizational performance with private and public sector strategic management frameworks. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11, 247–270.

Liston-Heyes, C., & Liu, G. (2010). Cause-related marketing in the retail and finance sectors: An exploratory study of the determinants of cause selection and nonprofit alliances. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39, 77–101.

Macher, J., & Richman, B. (2008). Transaction cost economics: An assessment of empirical research in the social sciences. Business and Politics, 10. http://www.bepress.com/bap/vol10/iss1/art1/, Accessed 2010.

Mannell, J. (2010). Are the sectors compatible? International development work and lessons for a business-nonprofit partnership framework. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 1106–1122.

Maple, P. (2003). Marketing strategy for effective fundraising. London: Directory of Social Change.

Martinez, C. V. (2003). Social alliances for fundraising: How Spanish nonprofits are hedging the risks. Journal of Business Ethics, 47, 209–222.

Martínez, C. V. (2003). Social alliance for fundraising: How Spanish nonprofits are hedging the risks. Journal of Business Ethics, 47, 209–222.

McAlexander, J., & Koenig, H. (2012). Building communities of philanthropy in higher education: Contextual influences. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17, 122–131.

McClusky, J. E. (2002). Re-thinking nonprofit organization governance: Implications for management and leadership. International Journal of Public Administration, 25, 539–559.

Mcdonald, S., & Young, S. (2012). Cross-sector collaboration shaping corporate social responsibility best practice within the mining industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.06.007.

Miles, R. E., Snow, C. C., Meyer, A. D., & Coleman, H. J., Jr. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and process. The Academy of Management Review, 3, 546–562.

Moore, M. H. (2000). Managing for value: Organizational strategy in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 183–208.

Moser, T. (2001). MNCs and sustainable business practice: The case of the Colombian and Peruvian petroleum industries. World Development, 29, 291–309.

Mutch, N. (2011). Does power imbalance matter in corporate-nonprofit partnerships? University of Otago.

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. The Academy of Management Review, 16, 145–179.

Osborne, S. (1996). Managing in the voluntary sector: A handbook for managers in charitable and nonprofit organizations. London: International Thomson Business Press.

Parker, B., & Selsky, J. W. (2004). Interface dynamics in cause-based partnerships: An exploration of emergent culture. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33, 458–488.

Peloza, J., & Falkenberg, L. (2009). The role of collaboration in achieving corporate social responsibility objectives. California Management Review, 51, 95–113.

Peterson, D. (2010). Agency perspectives on NGO governance. Journal of Management Research, 49(2), 4–10.

Pettigrew, A. (1985). The awakening giant: Continuity and change in ICL. Oxford: Blackwell.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1987). Context and action in the transformation of the firm. Journal of Management Studies, 24, 649–670.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1992). The character and significance of strategy process research. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 5–16.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1997). What is a processual analysis? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13, 337–348.

Pettigrew, A., & Whipp, R. (1991). Managing change for competitive success. Oxford: Blackwell.

Phillips, S. (2012). Canadian leapfrog: From regulating charitable fundraising to co-regulating good governance (pp. 1–22). Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74, 61–78.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80, 56–69.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62–77.

Press, A. (1998). Broken deal costs A.M.A. $9.9 million. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/08/03/us/broken-deal-costs-ama-9.9-million.html. Accessed July 2012.

Rondinelli, D., & London, T. (2003). How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 61–76.

Sargeant, A., & Kähler, J. (1999). Returns on fundraising expenditures in the voluntary sector. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 10, 5–19.

Sawhill, J. C., & Williamson, D. (2001). Mission impossible?: Measuring success in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11, 371–386.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31, 849–873.

Simpson, D., Lefroy, K. & Tsarenko, Y. (2011). Together and apart: Exploring structure of the corporate–NPO relationship. Journal of Business Ethics.

Struyk, R. J. (2002). Nonprofit organizations as contracted local social service providers in eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Public Administration and Development, 22, 429–437.

Thompson, J., & Martin, F. (2010). Strategic management: Awareness and change. London: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Thomson, A., & Perry, J. (2006). Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Administration Review, 66, 20–32.

Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Haugh, H. (2005). Beyond philanthropy: Community enterprise as a basis for corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 58, 327–344.

Tschirhart, M. (1996). Artful leadership: Managing stakeholder problems in nonprofit arts organizations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tschirhart, M., Christensen, R., & Perry, J. (2005). The paradox of branding and collaboration. Public Performance and Management Review, 29, 67–84.

Vakil, A. (1997). Confronting the classification problem: Toward a taxonomy of NGOs. World Development, 25, 2057–2070.

Waddock, S. A. (1989). Understanding social partnerships: An evolutionary model of partnership organizations. Administration & Society, 21, 78–100.

Weerawardena, J., McDonald, R. E., & Mort, G. S. (2010). Sustainability of nonprofit organizations: An empirical investigation. Journal of World Business, 45, 346–356.

Westley, F., & Vredenburg, H. (1991). Strategic bridging: The collaboration between environmentalists and business in the marketing of green products. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(1), 65–90.

Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2012). Understanding the importance of organizational resources to explain organizational problems: Evidence from nonprofit sport clubs in Germany (pp. 1–24). Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.

Wilson, E. J., Bunn, M. D., & Savage, G. T. (2010). Anatomy of a social partnership: A stakeholder perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 39, 76–90.

Wit, B. D., & Meyer, R. (2010). Strategy: Process, content, context; an international perspective. London: Thomson Learning.

World Bank. (2010). NGO research guide, World Bank and NGOs. http://library.duke.edu/research/subject/guides/ngo_guide/igo_ngo_coop/ngo_wb.html, Accessed March 2010.

Wymer, W. W., & Samu, S. (2003). Dimensions of business and nonprofit collaborative relationships. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 11, 3–22.

Yaziji, M. (2004). Turning gadflies into allies. Harvard Business Review, 82, 110–115.

Yaziji, M., & Doh, J. (2009). NGOs and corporations—conflict and collaboration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, D. R., & Steinberg, R. (1995). Economics for nonprofit managers. New York: Foundation Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

AL-Tabbaa, O., Leach, D. & March, J. Collaboration Between Nonprofit and Business Sectors: A Framework to Guide Strategy Development for Nonprofit Organizations. Voluntas 25, 657–678 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9357-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9357-6