Abstract

Purpose

Prevalence of peritoneal dialysis is low in part because of the perceived high risk for complications such as peritonitis. However, in the most recent era, peritonitis incidence and its effects on patient outcomes may have diminished. The aim of this study was to analyze peritonitis incidence and its impact on patient and technique survival, as well as on the kidney transplantation rate and outcome.

Methods

All peritoneal dialysis patients from a county hospital between year 2001 and 2011 were retrospectively included. Patients were divided into two groups with respect to peritonitis. The primary composite end-point consisted of a 3-year patient mortality or technique loss. Secondary end-points were patient survival and probability of kidney transplantation with respect to peritonitis history.

Results

Among 85 study patients, there were 61 peritonitis episodes. The incidence of peritonitis was 0.339 ± 0.71 episode per patient per 12 months or one episode per 29.3 ± 22.2 patient-months. The time to peritonitis was shorter, and peritonitis was more likely in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis than in automated peritoneal dialysis patients. Patient and technique survival and transplantation rate were similar in the group with and without peritonitis history. The primary end-point was recorded in 35 % of patients with peritonitis history and in 54 % of those without peritonitis (p = 0.04). In a multivariate analysis, the only variable significantly associated with the primary end-point and with patient survival was patient age at start of peritoneal dialysis.

Conclusions

In contemporary peritoneal dialysis patients, timely treated peritonitis may not be associated with adverse patient and technique outcomes. The transplantation rate is unaffected by the peritonitis history. Peritoneal dialysis may be promoted as the first dialysis method in appropriate patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global prevalence of peritoneal dialysis (PD) is unjustly low (8 % in 2008), with a substantial difference in its frequency among different countries [1]. Main reasons for the under usage of PD in many countries are fear of complications (mainly peritonitis), perceived better dialysis adequacy with hemodialysis (HD) and reimbursement issues [2]. In Croatia, PD prevalence is around 9 % and 5-year patient survival, both unadjusted and adjusted for age, gender, diabetes status and atherosclerosis, is somewhat better on PD, as compared to HD, except in patients with diabetes and in those older than 65 years in whom it is equal [3]. Similar results have been published for other countries [4]. Hence, PD is currently advocated in Croatia by the Croatian Renal Association as preferred initial dialysis modality in suitable patients. However, PD is associated with some specific complications, such as peritonitis, which may adversely affect patient outcomes [2]. Fortunately, better connectology, as well as better patient and medical staff education, has reduced incidence of peritonitis, according to majority [5–7], but not all data [8, 9]. In addition, earlier treatment of peritonitis may have reduced its severe complications, including patient death and technique loss. This retrospective study, in a contemporary cohort of PD patients from a single center, was undertaken to assess the frequency of peritonitis and to analyze its impact on patient and technique survival, as well as on the kidney transplantation rate and outcome.

Patients and methods

This is a single-center retrospective study. All PD patients followed at Zadar County Hospital, city of Zadar, Croatia, during a 10-year period between year 2001 and year 2011 were included. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital review board. Data were collected from the computer database and/or from the patient paper records. Patient histories were followed from the start of dialysis until January 2011. All peritonitis episodes were recorded, and for each peritonitis episode, causative microorganism was recorded, if isolated. Peritonitis was diagnosed according to the standard criteria: clinical signs of peritoneal inflammation or positive culture of peritoneal fluid or peritoneal fluid leukocyte count of >0.1 × 109/L [10]. Patients were divided into two groups: with or without peritonitis history. The primary end-point was a difference between the groups in the composite outcome consisting of a 3-year patient mortality or technique loss during 3 years. For that, end-point patients were censored at 3 years on PD or at the time of transplantation. A 3-year period was chosen as a time point because of an increased rate of transfer to HD with later time points for reasons likely unrelated to previous peritonitis episode. Secondary end-points were patient survival and probability of kidney transplantation with respect to the peritonitis history. Numerical data are presented as mean ± SD or as median and interquartile (IQ) range. Peritonitis incidence was calculated as the number of episodes divided by months at risk [10]. In addition, the mean time between peritonitis episodes was also calculated (months at risk divided by the number of peritonitis episodes per patient) [10]. The difference between two groups of continuous data was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The difference between the rates or frequencies was analyzed by the Chi-square test. Survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Survival rate comparison between two groups was done by the log-rank test. Association of candidate variables with survival rates was tested by the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis and is presented as hazard ratio (HR) with 95 % confidence interval (CI). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistica for Windows, v9.1 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

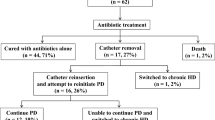

Demographical and selected clinical data of the study patients are presented in Table 1. There were 85 patients (33 female and 52 male). Their mean age at PD start was 56.6 ± 15.8 years (median 60 years; IQ range 46–67 years). A total of 24 patients (29.3 %) had diabetes. Throughout the study period, peritonitis occurred in 36 out of 85 patients (42.4 %), with the rate of 0.339 ± 0.71 episode per patient per 12 months, corresponding to one episode per 29.3 ± 22.2 patient-months. There were a total of 61 peritonitis episodes. Of those, there was one episode in 21 patients, two episodes in 11, three in two and four episodes in two patients. Nine out of 24 patients with diabetes (37 %) had peritonitis, as compared to 27 out of 61 patients without diabetes (44 %; n.s., Chi-square test). Similarly, the rate of peritonitis was similar regardless of diabetes status (25.5 ± 22.1 vs. 30.8 ± 22.2 patient-months; n.s., Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Patient age at start of PD was not different in those with and without peritonitis (data not shown). Predominant PD modality was continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD; 51 patients), while automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) was performed in the remaining 34 patients. A majority of peritonitis episodes (55; 90 %) occurred in patients on CAPD, and 6 occurred in patients on APD (p = 0.001, APD vs. CAPD, Chi-square test). In addition, besides higher incidence of peritonitis, CAPD was also associated with a shorter time to first peritonitis episode (p < 0.001, CAPD vs. APD, log-rank test). In the 55 % of episodes, peritonitis was caused by the Gram-positive bacteria (mainly coagulase-negative staphylococci, Streptococcus sp., Enterococcus sp. and S. aureus). Gram-negative bacteria (mainly E. coli and K. pneumoniae) were responsible for 26 % of episodes, while fungi were isolated from 7 % of samples. Cultures were negative in 12 % of episodes.

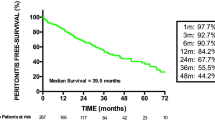

Long-term patient survival is depicted in Fig. 1. Overall patient survival was 75 % at 1 year, 55 % at 3 years and 37 % at 5 years (Fig. 1a). Patients with diabetes tended to have lower survival rate than other patients (p = 0.08; log-rank test). Patients who died during study period were older at initiation of PD (65.5 ± 10.4 years), as compared to patients who survived (51.5 ± 16.2 years, p = 0.001; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). There were no patient deaths during peritonitis episodes, and peritonitis history did not affect long-term patient survival (Fig. 1b). Patient age at start of dialysis was also the only significant predictor of mortality in a multivariate Cox regression (HR 1.03, HR CI 1.01–1.06; p < 0.01).

During the study period, 18 patients (21.2 %) switched to HD. PD method survival was 96.2 % at 1 year, 80.5 % at 3 years and 61.1 % at 5 years. PD method loss was not related to patient age (results not shown). The reason for switching to HD was: dialysis inadequacy in 6 patients, transfer to a center without PD in 5, fungal peritonitis in 4 and inability to perform PD in 3 patients. In patients without peritonitis, dialysis inadequacy (3 patients) and transfer to an HD-only center (3 patients) were principal reasons for switching to HD, while one patient stopped PD because of physical inability to perform PD. The change frequency in dialysis modality was similar in patients who had peritonitis and in those who did not have peritonitis (Fig. 2).

As shown in Fig. 3, composite primary end-point (switch to hemodialysis or patient mortality at 3 years) was recorded in 35 % of patients with peritonitis history and in 54 % of those without peritonitis (p = 0.04, log-rank test). If the whole study period has been taken into account, this statistical significance had been lost, as the survival curves converged. There was no difference in the primary end-point or in the mortality between patients who had one versus more than one peritonitis episode (data not shown). Patient age at start of dialysis was the only variable associated with the primary end-point in a multivariate Cox regression (HR 1.04, HR CI 1.01–1.07; p < 0.01).

Kidney transplantation was performed in 16 patients (18.8 %). The transplantation rate was equal, irrespective of peritonitis history (Fig. 4). In addition, there was no difference in kidney transplant rate between patients with one versus more than one episode of peritonitis (data not shown). Overall transplant patient survival was 100 %, with mean follow-up of 39.9 ± 32.0 months (median 35, IQ range 9.5–72.0 months).

Discussion

In the present study, we have analyzed, in a retrospective contemporary cohort of single dialysis unit PD patients, the impact of peritonitis on hard end-points—patient and technique survival and the chance for receiving a kidney transplant. None of the single end-points or combined primary end-point (patient mortality and technique loss) demonstrated negative impact of peritonitis. Our patients are educated to report to the dialysis unit as soon as they notice cloudy dialysate or at other signs and symptoms compatible with peritonitis. Therefore, diagnostic work-up and treatment can be started promptly, according to established protocol. In case of fungal peritonitis, the catheter is immediately removed. In Zadar hospital, all episodes of bacterial peritonitis are treated exclusively in-patient, and patients remain hospitalized throughout entire duration of antimicrobial treatment. We believe the in-patient treatment, guided by microbiology results (only 12 % of peritonitis episodes were culture-negative in the present study), may be the probable reason for an excellent patient and method survival in patients with peritonitis in this report. Hence, a paradox of a numerically (although not statistically) better survival in patients who experienced peritonitis (Fig. 1b), resulting also in a lower rate of primary end-point (Fig. 3), might reflect a possible closer general surveillance of these patients (initial hospitalization and more frequent patient visits following peritonitis episode). However, in a multivariate Cox regression analysis, the only variable independently associated with the primary end-point and with patient survival was patient age at start of dialysis. Our results regarding effect of peritonitis differ from two recently published studies [11, 12]. In a Spanish multicenter (Levante registry) analysis of a large cohort of PD patients who started PD between 1993 and 2005, an association of peritonitis with an increased long-term risk for mortality and technique failure was demonstrated [11]. Similar findings were published in a single-center report from Brazil [12]. Why these findings are different from ours is not clear, but both Spanish and Brazilian authors reported higher incidence of peritonitis than is at our center. In addition, a majority of patients were reported to have been treated as outpatients in the Levante registry study.

Peritonitis incidence was low in our cohort and was well within the goals stated by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis 2010 recommendations [10]. Decreased incidence rates of peritonitis and decreased mortality due to peritonitis in contemporary eras, as compared to previous periods, have been reported in some recent analyses [5–7]. Nevertheless, in recent multicenter English and Scottish surveys, either no improvement or even an increase in peritonitis rates was observed in more recent study cohorts [8, 9]. It is interesting that in our study, 90 % of peritonitis episodes occurred in patients on CAPD. This is in agreement with the majority of previous reports [8, 13], although there is some contrary data, as well [14]. Thus, taking the predominant evidence into account, it may be worthwhile to offer more patients APD in order to further reduce peritonitis incidence. In general, our findings regarding causative microorganisms of peritonitis are similar to other published data, with the predominance of coagulase-negative staphylococci [9, 15].

In Croatia, PD is advocated as the first dialysis modality in suitable patients, but as in many other countries, its prevalence is low (albeit modestly increasing), being 8.5 % at the end of 2010 [16]. The main reason for this is the lack of experience of many dialysis nephrologists with the method, as well as fear of complications, mainly of peritonitis. The “PD first” approach may be especially useful if kidney transplant is available in a relatively short time, because of a beneficial effect of PD on the preservation of residual renal function [2]. Consistently, there was no difference in renal graft or patient survival with respect to dialysis modality prior to kidney transplantation [17, 18]. Moreover, in some studies, PD has been associated with a decreased rate of delayed graft function after deceased-donor kidney transplantation [18] and even with a better patient and graft survival [19]. With an annual deceased-donor kidney transplantation rate in Croatia of approximately 50 pmp in 2010, which ranks Croatia among the top countries in Europe, 86 % of patients on the kidney transplantation waiting list now have dialysis vintage of ≤4 years [20]. This is reflected by the fact that 60 % of all deceased-donor kidney waiting list candidates get transplanted at the Merkur Hospital Transplant Centre within 4 years from the beginning of dialysis (Knotek, unpublished data), which is the time frame of a successful PD [3]. To further confirm that PD is a good pre-transplant option, we assessed in the present study the kidney transplant rate with respect to peritonitis history, as well as the kidney transplant outcome following PD. Peritonitis did not affect a chance for transplantation and did not affect transplant recipient survival (although the number of transplanted patients was too small for firm conclusion). Thus, with the “PD first” approach, it would be possible to use PD as the sole dialysis method in the majority of kidney transplant candidates, if the transplant rate is high, which would not only contribute to the overall reduction in dialysis cost, but might also contribute to better long-term graft and patient survival.

Our study has several limitations. It is a retrospective, single-center study, with low event rates. In addition, no comparison was made with the HD population. However, we believe it may serve as basis for some future prospective trials, for example, aimed at evaluating effects of hospitalization on outcome of peritonitis.

In conclusion, low incidence of peritonitis in contemporary PD patients, as well as lack of negative effects of peritonitis on patient survival and on the transplantation rate in our cohort, supports PD as the first dialysis modality.

References

Lameire N, Van BW (2010) Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis: a story of believers and nonbelievers. Nat Rev Nephrol 6:75–82

Chaudhary K, Sangha H, Khanna R (2011) Peritoneal dialysis first: rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6:447–456

Cala S (2007) Peritoneal dialysis in Croatia. Perit Dial Int 27:238–244

Burkart J (2009) The future of peritoneal dialysis in the United States: optimizing its use. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol l4(Suppl 1):S125–S131

Huang ST, Chuang YW, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Chen CH, Yu TM et al (2011) Evolution of microbiological trends and treatment outcomes in peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. Clin Nephrol 75:416–425

Li PK, Szeto CC (2008) Success of the peritoneal dialysis programme in Hong Kong. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23:1475–1478

Lim W, Dogra G, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Johnson DW (2011) Compared with younger peritoneal dialysis patients, elderly patients have similar peritonitis-free survival and lower risk of technique failure, but higher risk of peritonitis-related mortality. Perit Dial Int 31:663–671

Brown M, Simpson K, Kerssens JJ, Mactier R (2011) Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis rates and outcomes in a national cohort are not improving in the post-millennium (2000–2007). Perit Dial Int 31:639–650

Davenport A (2009) Peritonitis remains the major clinical complication of peritoneal dialysis: the London, UK, peritonitis audit 2002–2003. Perit Dial Int 29:297–302

Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, Bernardini J, Figueiredo AE, Gupta A et al (2010) Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int 30:393–423

Munoz de Bustillo E, Borras F, Gomez-Roldan C, Perez-Contreras FJ, Olivares J et al (2011) Impact of peritonitis on long-term survival of peritoneal dialysis patients. Nefrologia 31:723–732

Oliveira LG, Luengo J, Caramori JC, Montelli AC, Cunha MD, Barretti P (2012) Peritonitis in recent years: clinical findings and predictors of treatment response of 170 episodes at a single Brazilian center. Int Urol Nephrol [EPub ahead of print]

Rabindranath KS, Adams J, Ali TZ, Daly C, Vale L, Macleod AM (2007) Automated vs continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22:2991–2998

Balasubramanian G, McKitty K, Fan SL (2011) Comparing automated peritoneal dialysis with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: survival and quality of life differences? Nephrol Dial Transplant 26:1702–1728

Szeto CC, Kwan BC, Chow KM, Law MC, Pang WF, Leung CB et al (2011) Repeat peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: retrospective review of 181 consecutive cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6:827–833

Croatian Renal Replacement Therapy Registry on 31. 12. 2010; www.hdndt.org. Accessed on 16-06-2012

Caliskan Y, Yazici H, Gorgulu N, Yelken B, Emre T, Turkmen A et al (2009) Effect of pre-transplant dialysis modality on kidney transplantation outcome. Perit Dial Int 29(Suppl 2):S117–S122

Joseph JT, Jindal RM (2002) Influence of dialysis on post-transplant events. Clin Transplant 16:18–23

Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Hurdle JF, Scandling JD, Baird BC, Cheung AK (2005) The role of pretransplantation renal replacement therapy modality in kidney allograft and recipient survival. Am J Kidney Dis 46:537–549

Annual Report 2010. Eurotransplant. www.eurotransplant.org. Accessed on 1-12-2011

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klarić, D., Knotek, M. Long-term effects of peritonitis on peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Int Urol Nephrol 45, 519–525 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-012-0257-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-012-0257-2