Abstract

Bosniak classification system is the only preoperative diagnostic tool that has proven its efficiency in the management of complex renal cystic masses. However, it is reader dependent, despite its clear definition of each category. The overall incidence of malignancy in each category did not change significantly over the past 20 years. Current limitations are interobserver variability among readers and a fact that a significant proportion of Bosniak III masses have benign character. The goal is to depict these masses preoperatively and spare the patients of unnecessary surgeries, which raises the question: What particular findings will help in differentiating a Bosniak IIF lesion from a Bosniak III lesion? Do we need to define critical variables that could improve accuracy of Bosniak classification by developing a future nomogram or risk calculator? Some radiologists and urologists erroneously tend to group Bosniak II and IIF in one category and observe them regularly. It seems that radiographic growth itself is insufficient factor for intervention. The change of internal architecture and presence of enhancement play the most important role in depicting malignant lesions during the time frame of active surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cystic renal masses are usually classified according to the Bosniak classification. It was introduced in 1986, later modified and is now accepted by urologists and radiologists worldwide [1]. Five groups have been delineated including I, II, IIF, III, and IV. The Bosniak classification is based on findings of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), but can be also applied for MRI [1]. MRI in most circumstances offers no advantage over CT. However, in some cases, MRI can better demonstrate the septa and wall thickening when compared with CT [2]. In contrast, ultrasound plays a limited role in classifying cystic renal masses [1]. New technical improvements, such as contrast enhanced US may play a limited role in patients who are at risk for injection of iodinated or MR contrast media.

Details of the current classification are shown in (Table 1). Generally, management of renal cysts is largely dependent on the assigned group; however, there are still controversies in diagnosis and management of these lesions.

The basic morphological features of complex renal cysts are the presence of: (1) septa; (2) calcifications; (3) nodular or solid structures; and (4) enhancement. In the past, the presence of thick, nodular or irregular calcifications has placed the lesion into surgical Bosniak III category. Israel et al. have proved that according to the presence of calcifications alone, a lesion should not be classified as surgical. In their study, the value of calcification score was similar between surgical and non-surgical lesions [3] (Table 2). Therefore, the presence of thick, irregular calcifications may upgrade the Bosniak II lesion into Bosniak IIF category. The presence of enhancement is considered as the critical parameter to separate potentially benign from malignant lesions. It also seems that enhancement is one of the major determinants of progression for depicting malignant lesions during observation [4–7].

Diagnosis and management of Bosniak I and IV lesions is straightforward and usually leads to expectant or surgical management, respectively. Bosniak IIF masses, however, harbor a significant risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) that may be as high as 24% [4, 5, 7, 8] (Table 3). At most institutions, these cysts are only explored when they progress over time or become symptomatic. In Bosniak III category, a significant proportion of masses are malignant (0–100%, generally up to 50% are benign) [8–12] (Table 3). Differentiation of the malignant Bosniak III from benign masses on imaging is crucial in order to avoid unnecessary surgeries. The main problem from 1986 till 1993 was to differentiate some complicated Bosniak II from Bosniak III lesions. Bosniak II lesions that have some worrisome features (but not enough to categorize them to Bosniak III group) were suggested and designated as Bosniak IIF lesions [13] to establish their character during regular observation with CT or MRI. Certainly, this new category was beneficial and increased the incidence of malignancy in Bosniak III category [6], but could potentially increase the interobserver variability. Regular follow-up of CT, apart from the added expense, additional radiation exposure has potential, albeit low a risk of developing secondary malignancies.

[14]. Although the Bosniak classification system is the only preoperative diagnostic tool that has proven its efficiency in the management of complex renal cystic masses (CRCM), it is highly reader dependent despite clear definition of each category.

In this review, the authors point out diagnostic dilemmas and current controversies in the management of CRCM.

Bosniak II and IIF controversies

Follow-up of Bosniak IIF cystic masses has been proven as a safe management. Minimum of 5-year follow-up is important to determine the stability and benign nature of the mass. When the lesion progresses (in terms of enhancement, change in internal architecture by developing irregular, thick enhancing septa, solid component or multilocular character) on control CT scan or MRI, the lesion is upgraded and indicated for surgical revision [4]. Three patients from our group progressed, and the detection and presence of CT enhancement was the major indicator for surgery. Final histopathology confirmed RCC in all cases [23]. Similar results were recently observed by Gabr. et al., where 7 pts with Bosniak II and IIF progressed in terms of size, complexity, or enhancement. In 3 cases (1 pt with Bosniak II and 2 pts with Bosniak IIF), enhancement was detected as the parameter of progression, final histology confirmed malignancy [5].

Bosniak II and IIF cysts harbor more than 10% risk of having carcinoma (Table 3). The overall incidence of malignancy in both groups can be presumed to be much lower, because most of the masses are generally followed and only few of them are surgically resected.

Recently published study by O’Malley et al., with the largest cohort of Bosniak IIF lesions, has demonstrated 14.8% rate of progression. Three patients were lost on follow-up, 4 patients are still observed, while the progression was considered marginal or pts are in poor medical condition and in 5 surgically managed patients, RCC was confirmed [6] (Table 4).

The overall incidence of malignancy in Bosniak IIF can be influenced by interobserver variability, number of surgically resected lesions, presumed benign character based on radiographic stability, length of follow-up and the character of progression as well. Generally, increase in size does not result in surgical procedure. For that reason, it seems important to define the most accurate parameters of progression as the indicator for intervention in Bosniak II and IIF group (Table 4); furthermore, some radiologists tend to group these lesions in one category [5].

Major and minor criteria of Bosniak III lesions

Bosniak III lesion is a surgical lesion indicated for intervention, but the current dilemma is that significant proportion of benign lesions are in this category. The known interobserver variability was proved to be highest among Bosniak II and III masses [19]; however, Bosniak IIF category was not evaluated in that study. Recently Weibl [23] and Quaia et al. [24].showed a high rate of variability between Bosniak II, IIF and III groups.

In some cases, the management of Bosniak III mass may vary from center to center, regardless of the fact the Bosniak III is a surgical mass.

In some specific cases, one may seek for further diagnostic evaluation, such as: mass is indeterminate on CT [Fig. 1], young patients with completely intrarenal mass, which limits the nephron sparing procedure, relatively young patients with solitary kidney or on the contrary patients with short-term survival. In these cases, probably the indication for surgery will not be so straightforward or absolute.

Dedicated 4-phase CT scan or MRI is the basic tool for categorizing CRCM according to the Bosniak classification. Biopsy may be contributory especially when the infectious nature of the mass is suspected. However, negative biopsy does not exclude malignancy, that the lesion is not malignant, what is certainly frustrating as well for the urologist as for the patient. Role of biopsy of small renal masses and complex renal cysts is controversial [25], even though some authors recommend biopsy of indeterminate or Bosniak III masses with favorable results [26–28]. To date, there is no general consensus. The results of upcoming biopsy studies with potential oncomarkers may bring some new answers [29]. Even though biopsy or aspiration cytology in borderline cystic renal masses should be considered as one possible variable included in the development of risk calculator or a nomogram. Additionally integration of parameters such as age, ASA score, initial size, enhancement, growth rate and type of progression improves the decision-making process.

Active surveillance of surgical, potentially malignant complex renal cystic lesions is still considered to be experimental. High-risk patients with multiple comorbidities, with short-term overall survival and those who refuse any kind of intervention are potential candidates for this management. Long- and mid-term follow-up data are lacking. Until today, there is no clear consensus about the growth rate that warrants intervention for masses under active surveillance. That is why the growth itself is a not reliable and accurate predictor of malignancy and surgical intervention. As mentioned previously, again combination of more variables should improve the accuracy for intervention (size, radiographic growth, symptoms, type of progression, especially change in internal architecture of the cystic lesion).

Conclusion

Bosniak classification system has been established in 1986, proved its efficiency, but even after more than 20 years of clinical experience has some limitations. Current dilemmas and improvements are needed especially in Bosniak III category, because a significant proportion have benign character. Limitation such as interobserver variability among various readers with different levels of experience could be potentially improved by developing a normogram or a risk calculator. The goal is to specify which variables are the most relevant and accurate to be included in such a development. It is not a rare phenomenon that some urologist and radiologists tend to group some Bosniak II and IIF lesions in one category and observe them regularly. The crucial role in this group of patients is playing the parameters of progression. The radiographic growth itself is not a sufficient factor for intervention. The change of internal architecture and presence of enhancement play the most important role in depicting malignant lesions during the time frame of active surveillance.

References

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) An update on the Bosniak classification system. Urology 66(3):484–488

Israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak MA (2004) Evaluation of cystic masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology 231(2):365–371

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2003) Calcification in cystic renal masses: is it important in diagnosis? Radiology 226:47–521

Isreal GM, Bosniak MA (2003) Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney (Bosniak category IIF). AJR 181:627–633

Gabr AH, Gdor Y, Roberts WW, Wolf JS Jr (2008) Radiographic surveillance of minimally and moderately complex renal cysts. BJU Int 103:1116–1119

O’Malley RL, Godoy G, Hecht EM, Stifelman MD, Taneja SS (2009) Bosniak category IIF designation and surgery for complex renal cysts. J Urol 182:1091–1095

Weibl P, Lutter I, Breza J (2006) Follow-up of complex cystic lesions of the kidney Bosniak type II/IIF. Eur Urol Suppl 5(2):70

Wolf J Jr (1998) Evaluation and management of solid and cystic renal masses. J Urol 159(4):1120–1133

Bellman GC, Yamguchi R, Kaswick J (1995) Laparoscopic evaluation of indeterminate renal cysts. Urology 45(6):1066–1070

Koga S, Nishikido M, Inuzuka S, Sakamoto IHayashi T, Hayashi K, Saito Y, Kanetake H (2000) An evaluation of Bosniak classification of cystic renal masses. BJU Int 86:607–609

Spaliviero M, Herts BR, Magi-Galluzzi C, Xu M, Desai M, Kaouk J, Tucker K, Steinberg AP, Gill I (2005) Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for cystic masses. J Urol 714:614–619

Song Ch, Min GU, Song K, Kim JK, Hong B, Kim CS, Hanjong A (2009) Differential diagnosis of complex cystic renal mass using multiphase computerized tomography. J Urol 181(6):2446–2450

Bosniak MA (1993) Problems in the radiologic diagnosis of renal parenchymal tumors. In: Olsson CA, Sawczuk IS (eds) The urologic clinics of North America. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 217–230

Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007) Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. New Engl J Med 357(22):2277–2284

Brown WC, Amis ES Jr, Kaplan SA, Blaivas JG, Axelrod SL (1989) Renal cystic lessions: predictive value of preoperative computerized tomography. J Urol 141:426A

Aronson S, Frayier HA, Baluch JD, Hartman DS, Christenson PJ (1991) Cystic renal masses: usefulness of the Bosniak classification. Urol Radiol 13(2):83–90

Cloix P, Martin X, Pangaud C, Marechal JM, Bouvier R, Barat D, Dubernard JM (1996) Surgical management of complex renal cysts: a series of 32 cases. J Urol 3:564–570

Wilson TE, Doelle EA, Cohan RH, Wojno K, Korobkin M (1996) Cystic renal masses: a reevaluation of the usefulness of the Bosniak classification system. Acad Radiol 3:564–570

Siegel CL, McFarland EG, Brink JA, Fisher AJ, Humphrey P, Heiken JP (1997) CT of cystic renal masses: analysis of diagnostic performance and interobserver variation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:813–818

Bielsa GO, Arango TO, Cortadellas AR, Castro SR, Griñó Garreta J, Gelabert-Mas A (1999) The preoperative diagnosis of complex renal cystic masses. Arch Esp Urol 52(1):19–25

Curry NS, Cochran ST, Bissada NK (2000) Cystic renal masses: accurate Bosniak classification requires adequate renal CT. AJR Am J Ronentgenol 175:339–342

Limb J, Santiago L, Kaswick J, Bellman GC (2002) Laparoscopic evaluation of indeterminate renal cysts:long-term follow-up. J Endourol 16(2):79–82

Weibl P, Klatte T, Kollarik B, Geryk B, Schueller G, Marberger M, Remzi M (2010) Complex renal cystic masses: interpersonal variability of Bosniak classification is significant—fact or fiction. Eur Urol Suppl 9(2):298

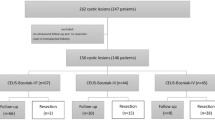

Quaia E, Bertolotto M, Cioffi V, Rossi A, Baratella E, Pizzolato R, Cova MA (2008) Comparison of contrast-enhanced sonography with unenhanced sonography and contrast enhanced CT in the diagnosis of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses. AJR 191:1239–1249

Remzi M, Marberger M (2009) Renal tumor biopsies for evaluation of small renal tumors: why, in whom, and how? Eur Urol 55(2):359–367

Harisinghani MG, Maher MM, Gervais DA, McGovern F, Hahn P, Jhaveri K, Varghese J, Mueller PR (2003) Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): Should imaging- guided biopsy precede surgery? AJR 180:755–758

Lang EK, Macchia RJ, Gayle B, Richter F, Watson RA, Thomas R, Myers L (2002) CT-guided biopsy of indeterminate renal cystic masses (Bosniak 3 and 2F): accuracy and impact on clinical management. Eur Radiol 12:2518–2524

Lechevalier E, Andre M, Barriol D, Daniel L, Eghazarian C, Fromont MD, Rossi D, Coulange C (2000) Fine-needle percutaneous biopsy of renal masses with helical CT guidance. Radiology 216:506–510

http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00491621 Study ID Number: 0501106

Conflicts of interest

I hereby certify that the manuscript or portions thereof are not under considerations by another journal or electronic publication and have not been previously published. Authors fully support this statement. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weibl, P., Klatte, T., Waldert, M. et al. Complex renal cystic masses: current standards and controversies. Int Urol Nephrol 44, 13–18 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-010-9864-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-010-9864-y