Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study is to provide an update on the imaging evaluation of cystic renal masses, to review benign and malignant etiologies of cystic renal masses, and to review current controversies and future directions in the management of these lesions.

Conclusions

Cystic renal masses are relatively common in daily practice. The Bosniak classification is a time-proven method for the imaging classification and management of these lesions. Knowledge of the pathognomonic features of certain benign Bosniak 2F/3 lesions is important to avoid surgery on these lesions (e.g., localized cystic disease, renal abscess). For traditionally surgical Bosniak lesions (Classes 3 and 4), there are evolving data that risk stratification based on patient demographics, imaging size, and appearance may allow for expanded management options including tailored surveillance or ablation, along with the traditional surgical approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cystic renal masses include both benign and malignant etiologies. The term “cystic” refers to a lesion that, on imaging, has a mostly fluid-filled growth pattern with a solid portion occupying a maximum of 25% of the tumor [1–3] or a mass that is predominantly composed of spaces filled with fluid [4]. Benign cystic renal masses include the very common simple renal cyst, seen on imaging in up to 17%–41% of patients imaged for other reasons [5, 6]. Benign simple cysts can be accurately diagnosed and need no further evaluation [7], therefore these simple cysts are typically accurately diagnosed and ignored on the initial imaging study which detected them. The primary clinical concern is accurately differentiating benign complex cystic renal masses from malignant complex cystic masses. The Bosniak classification system, introduced in 1986, provides an imaging framework for the differentiation of benign and malignant cystic renal masses, and the utility of the system has been repeatedly validated to date by the international urologic and radiologic communities [8–14].

This article will review the imaging evaluation of cystic renal masses, review benign/benign-behaving lesions that may fall into the Bosniak 2F, 3 ,or 4 category (but which have features that allow for accurate suggestion of benignity, such as localized cystic renal disease or a renal abscess), and will discuss malignant cystic renal masses and associated controversies around their diagnosis and management.

The Bosniak classification

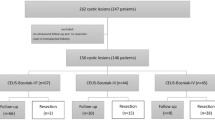

Renal cystic lesions are typically classified by the Bosniak classification system, which is based on CT findings and classifies a cystic renal mass into one of the five categories (1, 2, 2F, 3, and 4) on the basis of imaging features (Table 1; Fig. 1). In the Bosniak classification system, Bosniak 1 and 2 cystic lesions are benign and therefore, non-surgical. Bosniak category 2F (“F” for imaging follow-up), 3, and 4 lesions can have both benign and malignant etiologies, with malignancy rates increasing with increasing category. For example, malignancy rates have been reported (approximately) as 11% (range 5%–38%) for 2F lesions, 50% (range 25%–100%) for Bosniak 3 lesions, and 80% (range 67%–100%) for Bosniak 4 lesions [9, 15–19]. These rates are variable, likely secondary to different practice patterns of radiologists characterizing these lesions and urologists treating these lesions at different institutions [16, 17, 19]. Bosniak 2F lesions are typically managed by surveillance imaging. Traditionally, because of the high risk of malignancy of complex renal masses which fall in the Bosniak 3 and 4 categories, these two categories are considered best managed by surgical resection although imaging surveillance has been considered an acceptable alternative management approach in patients with a short-life expectancy or comorbidities.

Representative Bosniak category cysts. Contrast-enhanced (C+) CT in a 64-year-old man demonstrates 2 left-sided simple Bosniak 1 renal cysts (A) and in (B), a cyst with thin internal pencil thin septations and focal calcification compatible with a Bosniak 2 cyst. Axial C+ CT (C) demonstrating a peripherally calcified left anterior exophytic cystic lesion with chunky peripheral calcifications without solid enhancement consistent with a Bosniak 2F renal cyst (this was stable over multiple years of follow-up, and assumed to be benign). In (D) a C+ T1 3D gradient echo (GRE) MRI demonstrates a cyst with a slightly thickened internal septation, compatible with a Bosniak 2F cyst (this grew into a simple cyst on follow-up). Axial C+ CT in (E) demonstrates a cystic lesion with irregular peripheral wall thickening compatible with a Bosniak 3 lesion (this was a cystic papillary RCC on pathology). In (F), C+ T1 3D GRE MRI demonstrates a cystic Bosniak 4 lesion demonstrating solid nodular and thickened irregular septal enhancement medially (this was a cystic clear cell RCC on final pathology)

Categories 1 and 2 cysts are typically straightforward to diagnose and are benign, therefore do not require follow-up. Category 4 lesions (generally cystic neoplasms) are also typically readily diagnosed as malignant, and, by conservative standards, typically require surgery. Bosniak category 2F (“F” for follow-up) and 3 cystic masses can be difficult to differentiate. Category 2F lesions are more complicated than lesions in category 2, but without frank solid enhancing component (enhancement of a thickened septation or wall) as seen in category 3. Category 2F lesions require follow-up imaging (up to 4 years in one series [14]) to prove benignity, whereas Bosniak 3 lesions have more worrisome features which conventionally require surgery.

The gold standard of surgical resection for Bosniak 3 and 4 cystic renal masses has recently come under question for a number of reasons, including analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database which shows that despite the earlier detection and treatment of renal cancers, most of which are detected incidentally, the mortality rates from renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have steadily risen over the past 20 years [20–22]. This suggests that imaging detects many renal lesions that will not kill the patient, which in turn suggests that there is overdiagnosis and overtreatment of renal lesions. Cystic renal mass lesions, which represent 15% of all renal mass lesions [23, 24], are a minimal contributor to this mortality rate [1, 25–28] which is predominately mediated by the solid (or solid with necrosis), large, aggressive renal mass lesion, most of which are not cured by surgery, thus leaving the overall mortality rates of RCC unaffected by surgical intervention [21]. These studies also note that resection of renal masses is not without risk, especially since the greatest incidence of renal masses (cystic and solid) occur in patients 70 years old and older, in whom medical comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, renal disease, etc.) may increase the risks of radical or partial nephrectomy [29–31].

The ongoing clinical challenge therefore lies in the ability to definitively differentiate the benign (or benign-behaving) Bosniak 2F, 3, and 4 lesions from the malignant Bosniak 2F, 3, and 4 lesions, and to further evaluate which malignant cystic masses are amenable to more conservative management, in order to tailor treatment accurately [32–37].

Imaging evaluation of cystic renal masses (the Bosniak classification)

Computed tomography

Prior articles have described the appropriate imaging technique for adequate characterization of cystic renal masses [4, 9, 38, 39], and this is beyond the scope of this article. If the initial examination that detects the cystic renal mass is inadequate for characterization, then a dedicated renal mass CT or MRI can be performed, with gray-scale sonography reserved only for the characterization of specific lesions (described in detail below). The Bosniak classification is a CT-defined classification system [7, 40], and imaging performed on a multidetector CT scanner, using renal mass technique (non-contrast images through the kidneys, followed by post-contrast imaging in the nephrographic phase [41]) will characterize most renal cystic lesions. Known challenges in using CT for lesion characterization include the phenomenon of pseudoenhancement (the artifactual increase in attenuation on contrast-enhanced CT image by 10 Hounsfield units or more, thought to be secondary to beam hardening artifact) and the pitfall of partial volume averaging in small lesions (which occurs when the size of the lesion is less than twice the slice thickness used to scan) [42]. Mileto et al. recently demonstrated that virtual monochromatic imaging in dual energy MDCT may completely eliminate renal cyst pseudoenhancement in cysts larger than 1.5 cm [43].

Magnetic resonance imaging

Several papers have shown that renal mass MR imaging is equivalent to renal mass CT for the classification of cystic renal masses in the Bosniak classification system [16, 44, 45]. For detection of internal enhancement, particularly in hemorrhagic or calcified lesions, subtraction imaging can be used [39, 46, 47]. Known pitfalls with subtraction imaging in MRI include problems with image alignment (misregistration) and with discriminating signal from true internal enhancement from signal resulting from the additive noise on subtraction images [48]. An additional problem with MR imaging is secondary to its increased sensitivity for detection of subtle internal septations and wall thickening, particularly on T2-weighted images [44], as well as its superior contrast resolution compared to CT, both of which may cause less experienced readers of MRI to erroneously upgrade cystic renal lesions [16, 44, 49]. However, morphology alone (increased depiction of septations or apparent wall thickening) without associated enhancement does not upgrade a lesion in the Bosniak classification system; the morphologic change must be associated with enhancement. Advances in MR imaging with new sequences utilizing high-resolution free-breathing 3D fat-suppressed T1 gradient echo [50] allow improved detection and clarification of internal enhancement in small cystic renal masses. Diffusion-weighted imaging techniques cannot yet accurately differentiate a cystic renal mass from a simple renal cyst; however, preliminary studies have shown promising results [32, 37, 51–54]. Characterization of cystic renal masses can be challenging; for indeterminate CT scans, our institution tends to use contrast-enhanced MRI.

Gray-scale ultrasound

Gray-scale ultrasound without contrast is limited in its utility in the diagnosis of complex renal masses, with specific exceptions. Ultrasound is useful in characterizing cystic renal masses that measure between 20 and 40 HU on CT, as these lesions typically contain internal proteinaceous material and will appear simple on ultrasound, allowing for definitive characterization. It is limited in its utility for detecting small renal lesions [55]. The poor sensitivity to vascular flow of color Doppler techniques limits the technique to only describing morphology, which in the absence of contrast enhancement is inadequate for the accurate characterization of renal mass lesions. Morphology alone cannot upgrade a lesion in the Bosniak classification system; enhancement of that morphologic finding is the key [7, 40]. Pitfalls in gray-scale ultrasound without contrast include the erroneous upgrading of cystic renal masses that appear solid or contain internal debris [56]. However, if a cystic lesion is seen on ultrasound and meets criteria for a simple cyst (i.e., is anechoic, with a well-defined border and with increased posterior through-transmission), no further follow-up is necessary [57]. Renal cystic masses with an attenuation greater than 40 HU on CT are more likely to be hemorrhagic cysts and will therefore appear complex (and thus, indeterminate) on ultrasound [4]. Multiple recent articles have evaluated the accuracy of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluating cystic renal masses using the Bosniak classification, and the results have shown promise [58–61].

Size

Size is not a component of the Bosniak classification system, as small cystic renal masses can be malignant, and large cystic masses can be benign. However, size should arguably be considered an important consideration in the management of cystic renal lesions, as small renal lesions are more indolent than large renal lesions, just as cystic lesions are more indolent than solid lesions [21, 25, 62–67]. Small renal lesions smaller than 1.5 cm are overwhelmingly likely to be benign (excluding patients with a demographic/genetic predisposition to cancer) [68]. Incidental detection of a benign-appearing very small renal cystic mass in a patient with no risk factors for malignancy can be presumed benign and does not warrant further characterization [4].

Biopsy

Although some studies have suggested that biopsy of cystic renal masses is helpful in distinguishing benign from malignant etiologies [15], in general it is not a high-yield technique, secondary to the paucity of cells within cystic renal masses that limits a definitive sample and therefore, limits the likelihood of a definitive diagnosis from pathology. Biopsy/drainage is useful for cystic renal masses that are suspected to be renal abscesses, and may be useful in patients who are poor surgical candidates, with the caveat that frequently the sample may be insufficient to give a definitive diagnosis [21, 25, 62–68].

Benign/benign-behaving Bosniak 2F, 3, and 4 lesions

There are benign/benign-behaving lesions that may fall into the Bosniak 2F, 3, or 4 category but which have imaging features that may allow for the accurate suggestion of benignity. The benign lesions that can be confidently diagnosed as benign include localized cystic disease, pyelocalyceal diverticula/milk of calcium cysts, and calcified partially thrombosed pseudoaneurysms. Also included are the benign lesions where imaging may heavily suggest a benign diagnosis; however, tissue is ultimately needed to confirm the diagnosis. These lesions include the renal abscess, cystic nephroma (CN), and mixed epithelial stromal tumor (MEST).

Localized cystic disease is a benign process which is unilateral in all patients, and characterized by multiple cysts of various sizes separated by normal or atrophic renal tissue in a conglomerate mass that can be suggestive of a cystic neoplasm. The key to diagnosis is the ability to find a single cyst within the conglomerate mass, which is surrounded by normal renal parenchyma (Fig. 2).

Localized cystic disease. A 56-year-old man with contrast-enhanced CT images demonstrating a posterior cystic lesion in the midpole (A, B). A single cyst can be separated from the conglomeration of cysts, allowing for the diagnosis of localized cystic disease (this was, however, surgically resected and thus, surgically confirmed, as the referring urologist and patient chose to resect this lesion)

Pyelocalyceal diverticula are outpouchings of the renal collecting system that project into the renal cortex. These diverticula may contain stones, and should communicate with the collecting system (best depicted on excretory urographic phase images; Fig. 3).

A 68-year-old man with history of microhematuria. Axial pre-contrast CT (A), corticomedullary phase (B), and urographic phase images (C) through the left kidney demonstrate a thick-walled cyst in the left anterior interpolar region (A, B), which fills with excreted contrast on urographic phase images (C). Coronal MIP images through the kidneys (D) re-demonstrate the calyceal diverticulum

Milk of calcium cysts are thought to arise from pyelocalyceal diverticula which have internal precipitations of calcium salts. Typically these cysts have lost communication with the adjacent collecting system. On imaging, the internal precipitation will layer, and often will have a horizontal sharp upper border, and will not enhance post-contrast (Fig. 4).

A 44-year-old female with history of microscopic hematuria. Axial pre (A) and post-contrast (B) images through the right kidney demonstrate an endophytic cyst with internal layering calcium (A), which did not fill with contrast on corticomedullary (B) or urographic phase (not shown) images, compatible with a milk of calcium cyst

Although not a cystic renal mass, vascular etiologies should be considered in the diagnosis of a peripherally calcified renal cystic mass. When a peripherally calcified lesion is seen in the kidney, either Doppler ultrasound imaging or arterial phase CT or MR imaging should be performed to demonstrate internal signal/attenuation that follows the aortic signal/attenuation (Fig. 5).

A 62-year-old man with a remote history of trauma. In the right interpolar region, non-contrast (A), nephrographic phase (B), and delayed urographic phase (C) images demonstrate a peripherally thickly calcified renal cystic mass, with internal high attenuation (35 HU), but without appreciable enhancement. (Note the lack of an arterial phase on routine hematuria protocol CT limits the ability to evaluate for arterial lesions.) Follow-up C+ MR (D) demonstrates an internal blush of contrast that follows the signal of the aorta, allowing for the diagnosis of a renal pseudoaneurysm. Subsequent angiogram (E) at the time of embolization re-demonstrates the peripherally calcified pseudoaneurysm

Renal abscesses typically have a thickened peripheral rim with perilesional edema within the kidney. There is frequently mild stranding in the perirenal fat adjacent to the renal abscess (Fig. 6). In the setting of a lesion with this appearance, correlation with patient’s clinical symptoms (flank pain, urine analysis, urine cultures), imaging follow-up and/or tissue aspiration may be considered.

A 36-year-old female with right-sided abdominal pain and fever. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a thick-walled cystic lesion in the right renal interpolar region with poorly defined borders and mild adjacent capsular thickening (A, B), which resolved with antibiotic therapy, consistent with a renal abscess

Benign or benign-behaving renal neoplasms that cannot be confidently diagnosed on pre-operative imaging studies, and therefore may require surgical excision

Cystic Nephroma (CN) is a rare, non-familial tumor which has a bimodal age and sex distribution. In the pediatric population, it has a male predilection, whereas it affects middle-aged females in the adult population. CN herniates into the sinus and occasionally extends into the collecting system (Fig. 7).

A 50-year-old female with a Bosniak 4 cystic renal mass. Axial non-contrast (A) and post-contrast (B) images through the left kidney demonstrate a cystic mass with thickened enhancing internal septations and a solid nodular region of enhancement. Coronal urographic phase images through the left kidney (C) demonstrate herniation in the collecting system, a feature commonly described in cystic nephroma (CN). This was a CN on final pathology

A Mixed Epithelial Stromal Tumor (MEST) is currently thought to be a lesion on the same spectrum as the CN, with the vast majority of these lesions in middle-aged women, also occasionally demonstrating “herniation” in the collecting system [69, 70]. CN has a greater proportion of fluid and cysts within them, while MEST has a greater ovarian stromal component [71] (Fig. 8). Some pathologists have recommended use of the term renal epithelial and stromal tumor to refer to both CN and MEST [72].

A 45-year-old female with a Bosniak 4 right renal lesion. Axial pre-contrast (A) and post-contrast (B) CT images through the right kidney demonstrate a complex cystic lesion with thickening internal septations and soft tissue nodularity. There is herniation in the collecting system, a feature which can be seen in cystic nephroma (CN) or mixed epithelial stromal tumors (MESTs). However, even herniation in the collecting system can be seen in malignant lesions, therefore, this lesion was surgically resected, and was a MEST on final pathology

The multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma (MLCRCC) is a low-grade neoplasm of excellent prognosis. This lesion has a male predominance, with a male–female ratio of 3:1 [73]. Some pathologists suspect it is essentially benign as there are no cases of progression or metastases in reported series [26]. This lesion can range in appearance from a Bosniak 2F to a Bosniak 4 lesion, and it resembles a CN on gross pathology. It lacks solid nodules of carcinoma histologically. It is important to emphasize that there is no classic imaging feature that can suggest this benign-behaving neoplasm prior to surgical excision, and other malignant lesions (such as the cystic clear cell RCC) can have an identical appearance, therefore it is still considered a surgical lesion (Fig. 9).

Similar appearance of MLCRCC and cystic clear cell RCC. Coronal T2-weighted SSFSE images (A1) and axial post-contrast T1 GRE images through the right kidney (A2) in a middle-aged female demonstrate minimal thickened internal septations and subtle internal enhancement of septa (A2), compatible with a Bosniak 2F cystic lesion. This was a MLCRCC (multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma), a benign-behaving neoplasm, on final pathology. A different middle-aged female with a Bosniak 4 cystic renal lesion (enhancement was seen on post-contrast images; not shown) with coronal T2-weighted SSFSE images (B1, B2) through the left kidney demonstrates a cystic renal mass with thickened internal septations. This was a cystic clear cell RCC on final pathology

Malignant Bosniak 2F, 3, and 4 lesions

Malignant cystic RCCs are all rare compared with solid RCCs. These malignant cystic lesions include cystic clear cell carcinoma, the clear cell (tubulo) papillary RCC, tubulocystic carcinomas, and the benign-behaving MLCRCC.

Cystic cell carcinoma is a cystic mass with an irregularly thickened wall with large areas of solid nodularity within the wall. The demographic for this cystic tumor is identical to that of the clear cell solid RCC, with a male predominance (male:female ratio of 2:1), predominantly occurring in the sixth–seventh decades [74]. These cancers show extensive cystic change not resulting from necrosis, and are usually multiloculated. When there is no necrosis (based on careful analysis by the pathologist), these neoplasms are typically cured with resection [75] (Fig. 9).

The clear cell (tubulo) papillary RCC is composed of clear cells of low nuclear grade, with variable papillary tubular/acinar and cystic architecture. This tumor has no sex predilection, occurs at a mean age of 61 years, and usually presents at a low stage with indolent behavior and no metastases reported [76, 77].

Tubulocystic carcinoma is a mixture of tubules with micro- and macrocysts with low-grade nuclear features lined by a single layer of cuboidal or columnar cells with distinct nuclei that have a hobnail appearance. This lesion is also termed low-grade collecting duct carcinoma and Bellini duct carcinoma; this occurs mostly in men (85% male, 15% female) with a mean age of 54 years. The prognosis is excellent, with rare metastases [77, 78].

Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma

This is a benign-behaving neoplasm (also termed a neoplasm of low-malignant potential), which is almost entirely cystic, with the septa between the cystic components containing small clusters of clear cells without solid expansile nodules of clear cell carcinoma [79]. This lesion has a variable imaging appearance, ranging from a Bosniak 2F lesion to a Bosniak 4 lesion, with the Bosniak category corresponding to the degree of vascularized fibrosis within the lesion [26] (Fig. 9).

Solid renal neoplasms mimicking cystic renal cell carcinomas

Solid RCCs may mimic a cystic RCC; this either occurs secondary to a nearly absent internal enhancement in a hypovascular solid papillary RCC or an extensively necrotic solid RCC with a thickened rind of residual non-necrotic tumor [22]. Necrosis in a solid lesion can be, and has been, mistaken for an intrinsically cystic lesion (Fig. 10). In the Smith et al. article investigating the outcomes of cystic renal masses, 1 of the lesions prospectively read as a Bosniak 3 lesion (out of 113 total Bosniak 3 lesions) was a sarcomatoid RCC (presumably extensively necrotic), and while the patient had a history of a surgically resected solid papillary tumor, presumably the subsequent rapid tumor progression of the category 3 lesion and associated pulmonary metastases were secondary to this sarcomatoid tumor [18]. Similarly, in the same paper, a lesion prospectively classified as a Bosniak 4 lesion was a necrotic solid papillary RCC on pathology, and that patient eventually died of metastases from this lesion. The problem is, therefore, that solid necrotic tumors can be mistaken for cystic benign-behaving renal neoplasms on imaging. Solid papillary RCC without internal necrosis has been mistaken for a cystic lesion on imaging. This is because papillary carcinomas may have a partially cystic arrangement with papillae that variably fill a cystic space. For solid papillary renal lesions with a low density of papillae, the lesion will appear more cystic on pathology. Additionally, the solid variant of papillary RCC, composed of cells in tightly packed tubules can also mimic a cystic lesion on imaging, depending on the density of internal tissue [26, 80, 81]. It is also known that papillary RCCs are commonly hypovascular on imaging (such that they may not demonstrate internal contrast uptake to reach the threshold needed to suggest true enhancement within a lesion, i.e., typically an increase by ≥20 HU between pre and post-contrast CT, or solid internal enhancement on subtraction MR images; Fig. 11). In this way, these lesions may mimic a cystic non-enhancing renal lesion on imaging [82, 83]. Therefore, an overlap exists in imaging appearance between truly cystic lesions on histopathology (e.g., cystic clear cell RCC, MLCRCC, complicated hemorrhagic cysts, infected cysts) and solid papillary hypovascular tumors. Huber et al. suggested that a cystic appearance on imaging, regardless of the true pathology (i.e., cystic or solid) is associated with a lower-malignant potential in these lesions [2].

Solid tumor with hemorrhagic necrosis mimicking a cystic renal neoplasm. T2 weighted SSFSE sequence (A1) demonstrates a thick-walled cystic-appearing lesion. Pre-contrast T1 TSE (A2) shows high intensity signal within the lesion consistent with blood. In (A3), post-contrast T1 TSE sequence shows a thickened irregular solid wall with nodular projections. This degree of wall thickening (it measured up to 10 mm in thickness) is not consistent with a cystic neoplasm, and favors a solid, necrotic tumor. This was an extensively necrotic papillary RCC with hemorrhagic necrosis

A 79-year-old man with history of left-sided papillary RCC (not shown). In the lower pole of the right kidney, on T2 SSFSE (A1) there is a homogeneously dark lesion which is high signal on T1 FSE fat-saturated image (A2), with minimal suggestion of a faint curvilinear internal region of enhancement on subtraction images (A3). This was resected as it grew on follow-up images, and was a hypovascular solid papillary RCC without necrosis

Of course, these articles assume that a necrotic solid aggressive tumor is not placed into this category of cystic renal mass. Several articles offer guides to accurately diagnosing necrosis in a solid tumor and in better predicting true cystic pathology from cystic imaging appearance [2, 33]. For example, necrosis is typically centrally located in larger renal mass lesions. If a lesion with a thickened solid peripheral rind is seen, with non-enhancement centrally (Fig. 10), then necrosis in a solid tumor should be favored, and this lesion should not be categorized with the Bosniak classification as a Bosniak 4 lesion, but instead termed a solid necrotic mass [26, 80–84].

Demographics with increased risk

Several recent studies have described demographic features that are associated with an increased risk for malignancy in cystic renal lesions [85]. Smith et al. found an increased risk of malignancy in Bosniak categories 2F and 3 lesions in patients with a history of a primary renal malignancy, with a coexisting Bosniak category 4 cystic renal lesion or a solid renal mass (or both), and with multiple Bosniak category 3 renal lesions [19]. Similarly, we reported a trend toward increased risk for malignancy in Bosniak category 2F cysts in men more than 50 years old with a prior solid RCC [16]. Therefore, on the basis of these studies, in men over 50 years old with a history of a prior RCC (cystic or solid), the risk of malignancy in a cystic renal lesion appears to be increased relative to that of the general population. Larger studies of this subgroup of patients need to be performed to confirm this association.

Management recommendations

Recent review articles have outlined reasonable approaches to the management of both solid and cystic renal masses [4, 65, 86]. In sum, these recommendations generally follow the Bosniak categorization, with surgery recommended for Bosniak 3 and 4 lesions, and follow-up surveillance for Bosniak 2F lesions. Malignant cystic renal lesions are traditionally managed surgically (with partial nephrectomy as opposed to radical nephrectomy now considered the standard of care). However, there is an interest in more conservative management for these lesions in selected cases. Malignancy rates in Bosniak 2F, 3, and 4 lesions range from around 5% for Bosniak 2F lesions (lowest reported percentage in the literature) up to 100% for Bosniak 4 lesions. Some investigators are challenging whether, even in the case of true malignancy, cystic renal mass lesions are optimally treated by surgical removal. Data supporting this include reports that cystic RCCs have lower malignant potential than solid RCCs [16, 17, 20, 21], as long as extensively necrotic solid RCCs are not mistaken for cystic renal lesions [22]. The reports that show that cystic renal lesions are benign-behaving rely on the accurate diagnosis of these lesions as cystic on both imaging and on pathology (e.g., Bosniak 3 and 4 lesions that on surgical resection prove to be MLCRCC, cystic clear cell RCC, or cystic papillary RCC). These favorable prognostic reports do not account for highly aggressive solid necrotic lesions that are mistakenly rarely placed into the “cystic” category [18].

Size is becoming a factor in management, with some recommendations now more liberally allowing for the incidentally (in an otherwise healthy individual) very small cystic renal lesion (less than 2 or 1.5 cm in size, depending on the paper) which is benign-appearing (within limitations of the imaging modality) to be definitively called a simple cyst and be ignored [14, 68]. Surveillance imaging is cautiously being used even for solid tumors (mean size 7.1 cm in the Mues et al. series) in selected (elderly patients with comorbidities) patient populations, with most patients not progressing to metastases even in these high-risk large tumors (progression to metastatic disease seen in 2/36 patients (5.6%)) [14, 87, 88]. If extrapolated to cystic renal masses, which are more indolent than solid tumors, then selected patients with Bosniak 3 and 4 lesions are candidates for surveillance imaging. Almost all series to date report the absence of recurrence or metastases after surgical resection of Bosniak 2F and 3 lesions, with favorable outcomes after surgical resection of Bosniak 4 lesions [16, 19, 89–91]. It will require further study to see if observation of these lesions will prove safe.

The role of ablation in the treatment of cystic renal masses has not yet been delineated. Smith et al. has suggested that there are less complications and lower cost associated with cystic renal mass ablation, as opposed to surgery [18]. However, ablation is only selectively utilized for cystic renal masses, depending on the size and location of the cystic lesion [92, 93].

Summary

In conclusion, cystic renal masses are relatively common in daily practice. The Bosniak classification is a time-proven method for the imaging classification and management of these lesions. Knowledge of the pathognomonic features of certain benign Bosniak 2F/3 lesions is important to avoid surgery on these lesions (e.g., localized cystic disease, renal abscess). For traditionally surgical Bosniak lesions (Bosniak categories 3 and 4), there are evolving data that risk stratification based on patient demographics, imaging size, and appearance may allow for expanded management options, including tailored surveillance ablation, along with the traditional surgical approach.

References

Corica FA, Iczkowski KA, Cheng L, et al. (1999) Cystic renal cell carcinoma is cured by resection: a study of 24 cases with long-term followup. J Urol 161(2):408–411

Huber J, Winkler A, Jakobi H, et al. (2014) Preoperative decision making for renal cell carcinoma: cystic morphology in cross-sectional imaging might predict lower malignant potential. Urol Oncol 32(1):37.e31–37.e36. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.02.016

Park HS, Lee K, Moon KC (2011) Determination of the cutoff value of the proportion of cystic change for prognostic stratification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 186(2):423–429. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.107

Silverman SG, Israel GM, Herts BR, Richie JP (2008) Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology 249(1):16–31. doi:10.1148/radiol.2491070783

Carrim ZI, Murchison JT (2003) The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clin Radiol 58(8):626–629

O’Connor SD, Silverman SG, Ip IK, Maehara CK, Khorasani R (2013) Simple cyst-appearing renal masses at unenhanced CT: Can they be presumed to be benign? Radiology 269(3):793–800. doi:10.1148/radiol.13122633

Bosniak MA (1986) The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology 158(1):1–10. doi:10.1148/radiology.158.1.3510019

Cloix P, Martin X, Pangaud C, et al. (1996) Surgical management of complex renal cysts: a series of 32 cases. J Urol 156(1):28–30

Curry NS, Cochran ST, Bissada NK (2000) Cystic renal masses: accurate Bosniak classification requires adequate renal CT. Am J Roentgenol 175(2):339–342

Levy P, Helenon O, Merran S, et al. (1999) Cystic tumors of the kidney in adults: radio-histopathologic correlations. J radiol 80(2):121–133

Graumann O, Osther SS, Karstoft J, Horlyck A, Osther PJ (2015) Bosniak classification system: a prospective comparison of CT, contrast-enhanced US, and MR for categorizing complex renal cystic masses. Acta radiol . doi:10.1177/0284185115588124

Warren KS, McFarlane J (2005) The Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses. BJU Int 95(7):939–942. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05442.x

Koga S, Nishikido M, Inuzuka S, et al. (2000) An evaluation of Bosniak’s radiological classification of cystic renal masses. BJU Int 86(6):607–609

Silverman SG, Israel GM, Trinh QD (2015) Incompletely characterized incidental renal masses: emerging data support conservative management. Radiology 275(1):28–42. doi:10.1148/radiol.14141144

Harisinghani MG, Maher MM, Gervais DA, et al. (2003) Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): Should imaging-guided biopsy precede surgery? Am J Roentgenol 180(3):755–758

Hindman NM, Hecht EM, Bosniak MA (2014) Follow-up for Bosniak category 2F cystic renal lesions. Radiology 272(3):757–766. doi:10.1148/radiol.14122908

O’Malley RL, Godoy G, Hecht EM, Stifelman MD, Taneja SS (2009) Bosniak category IIF designation and surgery for complex renal cysts. J Urol 182(3):1091–1095. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.046

Smith AD, Allen BC, Sanyal R, et al. (2015) Outcomes and complications related to the management of Bosniak cystic renal lesions. Am J Roentgenol 204(5):W550–W556. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.13149

Smith AD, Remer EM, Cox KL, et al. (2012) Bosniak category IIF and III cystic renal lesions: outcomes and associations. Radiology 262(1):152–160. doi:10.1148/radiol.11110888

Hollenbeck BK, Taub DA, Miller DC, Dunn RL, Wei JT (2006) Use of nephrectomy at select medical centers—a case of follow the crowd? J Urol 175(2):670–674. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00146-1

Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK (2006) Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst 98(18):1331–1334. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj362

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. (eds) (2013) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2011. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute

Hartman DS, Davis CJ Jr, Johns T, Goldman SM (1986) Cystic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 28(2):145–153

Moch H (2010) Cystic renal tumors: new entities and novel concepts. Adv Anat Pathol 17(3):209–214. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181d98c9d

Han KR, Janzen NK, McWhorter VC, et al. (2004) Cystic renal cell carcinoma: biology and clinical behavior. Urol Oncol 22(5):410–414. doi:10.1016/S1078-1439(03)00173-X

Hindman NM, Bosniak MA, Rosenkrantz AB, Lee-Felker S, Melamed J (2012) Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma: comparison of imaging and pathologic findings. Am J Roentgenol 198(1):W20–W26. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.6762

Koga S, Nishikido M, Hayashi T, et al. (2000) Outcome of surgery in cystic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 56(1):67–70

Winters BR, Gore JL, Holt SK, et al. (2015) Cystic renal cell carcinoma carries an excellent prognosis regardless of tumor size. Urol Oncol 33(12):505.e509–505.e513. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.07.017

Kouba E, Smith A, McRackan D, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS (2007) Watchful waiting for solid renal masses: insight into the natural history and results of delayed intervention. J Urol 177(2):466–470; discussion 470. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.064

Rendon RA, Stanietzky N, Panzarella T, et al. (2000) The natural history of small renal masses. J Urol 164(4):1143–1147

Shuch B, Hanley JM, Lai JC, et al. (2014) Adverse health outcomes associated with surgical management of the small renal mass. J Urol 191(2):301–308. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.08.074

Shinagare AB, Vikram R, Jaffe C, et al. (2015) Radiogenomics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: preliminary findings of The Cancer Genome Atlas-Renal Cell Carcinoma (TCGA-RCC) Imaging Research Group. Abdom Imaging 40(6):1684–1692. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0386-z

Pedrosa I, Chou MT, Ngo L, et al. (2008) MR classification of renal masses with pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol 18(2):365–375. doi:10.1007/s00330-007-0757-0

Italiano A (2011) Prognostic or predictive? It’s time to get back to definitions! J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 29(35):4718; author reply 4718–4719. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3729

Kuo MD, Jamshidi N (2014) Behind the numbers: decoding molecular phenotypes with radiogenomics-guiding principles and technical considerations. Radiology 270(2):320–325. doi:10.1148/radiol.13132195

Doshi AM, Huang WC, Donin NM, Chandarana H (2015) MRI features of renal cell carcinoma that predict favorable clinicopathologic outcomes. Am J Roentgenol 204(4):798–803. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.13227

Kang SK, Zhang A, Pandharipande PV, et al. (2015) DWI for renal mass characterization: systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test performance. Am J Roentgenol 205(2):317–324. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.13930

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology 236(2):441–450. doi:10.1148/radiol.2362040218

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2004) MR imaging of cystic renal masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 12(3):403–412, v. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2004.03.006

Bosniak MA (2012) The Bosniak renal cyst classification: 25 years later. Radiology 262(3):781–785. doi:10.1148/radiol.11111595

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) An update of the Bosniak renal cyst classification system. Urology 66(3):484–488. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.003

Birnbaum BA, Hindman N, Lee J, Babb JS (2007) Renal cyst pseudoenhancement: influence of multidetector CT reconstruction algorithm and scanner type in phantom model. Radiology 244(3):767–775. doi:10.1148/radiol.2443061537

Mileto A, Nelson RC, Marin D, Choudhury KR, Ho LM (2014) Dual-energy multidetector CT for the characterization of incidental adrenal nodules: diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced material density analysis. Radiology. doi:10.1148/radiol.14140876

Israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak MA (2004) Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology 231(2):365–371. doi:10.1148/radiol.2312031025

Balci NC, Semelka RC, Patt RH, et al. (1999) Complex renal cysts: findings on MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol 172(6):1495–1500. doi:10.2214/ajr.172.6.10350279

Hecht EM, Israel GM, Krinsky GA, et al. (2004) Renal masses: quantitative analysis of enhancement with signal intensity measurements versus qualitative analysis of enhancement with image subtraction for diagnosing malignancy at MR imaging. Radiology 232(2):373–378. doi:10.1148/radiol.2322031209

Kim S, Jain M, Harris AB, et al. (2009) T1 hyperintense renal lesions: characterization with diffusion-weighted MR imaging versus contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 251(3):796–807. doi:10.1148/radiol.2513080724

Heverhagen JT (2007) Noise measurement and estimation in MR imaging experiments. Radiology 245(3):638–639. doi:10.1148/radiol.2453062151

Rosenkrantz AB, Wehrli NE, Mussi TC, Taneja SS, Triolo MJ (2014) Complex cystic renal masses: comparison of cyst complexity and Bosniak classification between 1.5 T and 3 T MRI. Eur J Radiol 83(3):503–508. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.11.013

Chandarana H, Block TK, Rosenkrantz AB, et al. (2011) Free-breathing radial 3D fat-suppressed T1-weighted gradient echo sequence: a viable alternative for contrast-enhanced liver imaging in patients unable to suspend respiration. Investig Radiol 46(10):648–653. doi:10.1097/RLI.0b013e31821eea45

Rosenkrantz AB, Niver BE, Fitzgerald EF, et al. (2010) Utility of the apparent diffusion coefficient for distinguishing clear cell renal cell carcinoma of low and high nuclear grade. Am J Roentgenol 195(5):W344–W351. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.4688

Chandarana H, Kang SK, Wong S, et al. (2012) Diffusion-weighted intravoxel incoherent motion imaging of renal tumors with histopathologic correlation. Investig Radiol 47(12):688–696. doi:10.1097/RLI.0b013e31826a0a49

Squillaci E, Manenti G, Di Stefano F, et al. (2004) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the evaluation of renal tumours. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 23(1):39–45

Zhang J, Tehrani YM, Wang L, et al. (2008) Renal masses: characterization with diffusion-weighted MR imaging—a preliminary experience. Radiology 247(2):458–464. doi:10.1148/radiol.2472070823

Jamis-Dow CA, Choyke PL, Jennings SB, et al. (1996) Small (< or =3-cm) renal masses: detection with CT versus US and pathologic correlation. Radiology 198(3):785–788. doi:10.1148/radiology.198.3.8628872

Bosniak MA (1991) Difficulties in classifying cystic lesions of the kidney. Urol Radiol 13(2):91–93

Chang YW, Kwon KH, Goo DE, et al. (2007) Sonographic differentiation of benign and malignant cystic lesions of the breast. J Ultrasound Med 26(1):47–53

Ascenti G, Mazziotti S, Zimbaro G, et al. (2007) Complex cystic renal masses: characterization with contrast-enhanced US. Radiology 243(1):158–165. doi:10.1148/radiol.2431051924

Clevert DA, Minaifar N, Weckbach S, et al. (2008) Multislice computed tomography versus contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluation of complex cystic renal masses using the Bosniak classification system. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 39(1–4):171–178

Ignee A, Straub B, Brix D, et al. (2010) The value of contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the characterisation of patients with renal masses. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 46(4):275–290. doi:10.3233/CH-2010-1352

Park BK, Kim B, Kim SH, et al. (2007) Assessment of cystic renal masses based on Bosniak classification: comparison of CT and contrast-enhanced US. Eur J Radiol 61(2):310–314. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.10.004

Chawla SN, Crispen PL, Hanlon AL, et al. (2006) The natural history of observed enhancing renal masses: meta-analysis and review of the world literature. J Urol 175(2):425–431. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00148-5

Hollenbeck BK, Taub DA, Miller DC, Dunn RL, Wei JT (2006) National utilization trends of partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a case of underutilization? Urology 67(2):254–259. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.050

Webster WS, Thompson RH, Cheville JC, et al. (2007) Surgical resection provides excellent outcomes for patients with cystic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology 70(5):900–904; discussion 904. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.029

Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. (2010) Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 7(10):754–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2010.06.013

Thompson RH, Hill JR, Babayev Y, et al. (2009) Metastatic renal cell carcinoma risk according to tumor size. J Urol 182(1):41–45. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.128

Volpe A, Panzarella T, Rendon RA, et al. (2004) The natural history of incidentally detected small renal masses. Cancer 100(4):738–745. doi:10.1002/cncr.20025

Hindman NM (2015) Approach to very small (< 1.5 cm) cystic renal lesions: ignore, observe, or treat? Am J Roentgenol 204(6):1182–1189. doi:10.2214/AJR.15.14357

Horikawa M, Shinmoto H, Kuroda K, et al. (2012) Mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney with polypoid component extending into renal pelvis and ureter. Acta radiol Short Rep. doi:10.1258/arsr.2011.110010

Wood CG III, Stromberg LJ III, Harmath CB, et al. (2015) CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am 35(1):125–141. doi:10.1148/rg.351130016

Jevremovic D, Lager DJ, Lewin M (2006) Cystic nephroma (multilocular cyst) and mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney: a spectrum of the same entity? Ann Diagn Pathol 10(2):77–82. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.07.011

Turbiner J, Amin MB, Humphrey PA, et al. (2007) Cystic nephroma and mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of kidney: a detailed clinicopathologic analysis of 34 cases and proposal for renal epithelial and stromal tumor (REST) as a unifying term. Am J Surg Pathol 31(4):489–500. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802bdd56

Chowdhury AR, Chakraborty D, Bhattacharya P, Dey RK (2013) Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma a diagnostic dilemma: a case report in a 30-year-old woman. Urol Ann 5(2):119–121. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.110012

Imura J, Ichikawa K, Takeda J, et al. (2004) Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathological, immuno- and lectin histochemical study of nine cases. Acta pathol microbiol immunol Scand 112(3):183–191. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120304.x

Brinker DA, Amin MB, de Peralta-Venturina M, et al. (2000) Extensively necrotic cystic renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study with comparison to other cystic and necrotic renal cancers. Am J Surg Pathol 24(7):988–995

Williamson SR, Eble JN, Cheng L, Grignon DJ (2013) Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: differential diagnosis and extended immunohistochemical profile. Mod Pathol 26(5):697–708. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.204

Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, et al. (2013) The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver classification of renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 37(10):1469–1489. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1

MacLennan GT, Farrow GM, Bostwick DG (1997) Low-grade collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney: report of 13 cases of low-grade mucinous tubulocystic renal carcinoma of possible collecting duct origin. Urology 50(5):679–684. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00335-X

Halat S, Eble JN, Grignon DJ, et al. (2010) Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma is a subtype of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 23(7):931–936. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2010.78

Allory Y, Ouazana D, Boucher E, Thiounn N, Vieillefond A (2003) Papillary renal cell carcinoma. Prognostic value of morphological subtypes in a clinicopathologic study of 43 cases. Virchows Arch Int J Pathol 442(4):336–342. doi:10.1007/s00428-003-0787-1

Bielsa O, Lloreta J, Gelabert-Mas A (1998) Cystic renal cell carcinoma: pathological features, survival and implications for treatment. Br J Urol 82(1):16–20

Pierorazio PM, Hyams ES, Tsai S, et al. (2013) Multiphasic enhancement patterns of small renal masses (</=4 cm) on preoperative computed tomography: utility for distinguishing subtypes of renal cell carcinoma, angiomyolipoma, and oncocytoma. Urology 81(6):1265–1271. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.12.049

Young JR, Margolis D, Sauk S, et al. (2013) Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: discrimination from other renal cell carcinoma subtypes and oncocytoma at multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology 267(2):444–453. doi:10.1148/radiol.13112617

Karlo CA, Di Paolo PL, Chaim J, et al. (2014) Radiogenomics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: associations between CT imaging features and mutations. Radiology 270(2):464–471. doi:10.1148/radiol.13130663

Goenka AH, Remer EM, Smith AD, et al. (2013) Development of a clinical prediction model for assessment of malignancy risk in Bosniak III renal lesions. Urology 82(3):630–635. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.05.016

Silverman SG, Gan YU, Mortele KJ, Tuncali K, Cibas ES (2006) Renal masses in the adult patient: the role of percutaneous biopsy. Radiology 240(1):6–22. doi:10.1148/radiol.2401050061

Mues AC, Haramis G, Badani K, et al. (2010) Active surveillance for larger (cT1bN0M0 and cT2N0M0) renal cortical neoplasms. Urology 76(3):620–623. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.04.021

Haramis G, Mues AC, Rosales JC, et al. (2011) Natural history of renal cortical neoplasms during active surveillance with follow-up longer than 5 years. Urology 77(4):787–791. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.09.031

Hwang JH, Lee CK, Yu HS, et al. (2012) Clinical outcomes of Bosniak category IIF complex renal cysts in Korean patients. Korean J Urol 53(6):386–390. doi:10.4111/kju.2012.53.6.386

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2003) Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney (Bosniak category IIF). Am J Roentgenol 181(3):627–633. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.3.1810627

Jhaveri K, Gupta P, Elmi A, et al. (2013) Cystic renal cell carcinomas: Do they grow, metastasize, or recur? Am J Roentgenol 201(2):W292–W296. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.9414

Carrafiello G, Dionigi G, Ierardi AM, et al. (2013) Efficacy, safety and effectiveness of image-guided percutaneous microwave ablation in cystic renal lesions Bosniak III or IV after 24 months follow up. Int J Surg 11(Suppl 1):S30–S35. doi:10.1016/S1743-9191(13)60010-2

Felker ER, Lee-Felker SA, Alpern L, Lu D, Raman SS (2013) Efficacy of imaging-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of biopsy-proven malignant cystic renal masses. Am J Roentgenol 201(5):1029–1035. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.10210

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This was not a funded study.

Conflicts of interest

Nicole M. Hindman has no funding nor any conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study complied with ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hindman, N.M. Cystic renal masses. Abdom Radiol 41, 1020–1034 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-016-0761-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-016-0761-4