Abstract

Catalytic dehydrogenation is a critical and growing technology for the production of olefins, especially for propylene production. This paper will give an overview of advances in the catalysis science and technology for production of olefins by catalytic dehydrogenation, including the concomitant removal of H2 by selective oxidation. For light paraffin dehydrogenation, UOP has licensed the Oleflex™ process widely for production of polymer-grade propylene as well as isobutylene with over 12 million metric tons of capacity announced. Today there are nine UOP C3 Oleflex™ units in operation accounting for 55 % of the installed world-wide propylene production capacity from propane dehydrogenation technology. The heart of the process is a noble metal multi-metallic catalyst and the continuous catalyst regeneration (CCR) process. The coupling of catalytic dehydrogenation with selective oxidation of hydrogen allows one to design a process, which greatly improves equilibrium conversions while maintaining very high selectivity to olefin. The Lummus/UOP SMART™ SM process (Styrene Monomer Advanced Reheat Technology) allows 30–70 % capacity expansion, achieves a higher per-pass ethylbenzene conversion, and provides the most cost-effective revamp for higher capacity. Styrene Monomer Advanced Reheat Technology (SMART™) uses an oxidation catalyst and novel reactor internals to allow oxidative reheating between dehydrogenation stages. In the case of selective oxidation catalysts containing dispersed metal active sites, the role of diffusion and pore architecture is as important as the active metal sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

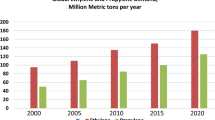

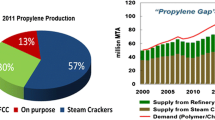

The dehydrogenation of propane to produce propylene has become a critical technology to fill the propylene shortage, which is increasing due to the portion of steam crackers now using inexpensive ethane feedstock [1]. This trend is expected to continue in the near future due to the abundance of wet shale gas worldwide [2]. As evidence, over 5 million tons of on-purpose propane dehydrogenation capacity is expected in the next 5 years.

In this Catalysis Topics Edition, UOP’s Bipin Vora has already discussed in detail the thermodynamics and process aspects of catalytic dehydrogenation for the production of olefins including an introduction of important catalyst design principles. In this paper, we will discuss in more detail the aspects of catalyst design and performance for catalytic dehydrogenations.

2 Discussion

2.1 Process Chemistry

Briefly, the main considerations in the catalytic dehydrogenation are the high reaction enthalpy, 30 kcal/mol, and the thermodynamic equilibrium limitations. These two factors require the process to operate at high temperatures (>600 °C) and lower pressures (<30 psig) to achieve economic conversion levels. These process conditions, in turn, set the primary requirements for the dehydrogenation catalyst design in order to achieve high selectivity at high conversion with sufficient stability.

2.2 Catalyst Design

As in any catalyst design, achieving high activity and selectivity for paraffin dehydrogenation catalysts requires control of both chemical and mass transport properties. We will address mass transfer first.

2.3 Mass Transfer

The most common approaches for eliminating intraparticle pore diffusional limitations in catalytic dehydrogenations are:

-

(1)

Reducing the physical diffusion path in the catalyst particle by employing smaller particles, shaped particles such as trilobes, and monolithic supports.

-

(2)

Modifying the pore architecture to improve feed and product diffusion rates.

-

(3)

Employing methodologies to achieve a higher surface concentration of active component in the catalyst support pellet.

The choice of approach is generally dictated by the process design features of the overall process as well as the nature of the effective catalysts. For example, it is possible to completely eliminate pore diffusion by using fluidized bed ca. 80 micron particles in noble metal dehydrogenations. However, containment of catalyst and recovery of valuable fines makes it generally unappealing.

In the field of eliminating mass transfer in dehydrogenation and selective oxidation catalysis, very significant inventions and contributions to the field have been made by Imai, Abrevaya, Rende, Vora, DY-Jan, QChen, FXu, JWA Sachtler, MLBricker, Woodle, and Jensen [3–14]. As Vora has pointed out, alumina supported catalysts are preferred for selected paraffin dehydrogenation chemistry [11]. For example, Table 1 shows the performance of three Pt–alumina catalysts, with identical composition and dispersion, having average pore diameters varying by a factor of seven. Compared with the gamma alumina catalyst A, the larger pore catalyst B shows superior activity, selectivity, and stability for olefin production. There is a limit to this approach as increasing pore diameter too far, as for Catalyst C, is accompanied by lower available surface area to disperse the metals, hence, activity is reduced significantly.

Likewise, the use of shaped particles imparts improved selectivity and activity for heavy paraffin dehydrogenation relative to spheres, as shown in Table 2. Here, there is a strong correlation of surface to volume ratio of the particle to performance. In this set of data, the surface to volume ratio accurately reflects the critical diffusion path. For processes requiring moving bed technology, the application of shaped particles can be limiting.

The data show that a certain point, with meshed catalyst F, the extra surface/volume ratio imparts an unacceptably large pressure drop, which will limit equilibrium conversion across multiple catalyst beds. The trilobular catalyst improves selectivity without increasing pressure drop. This is due primarily by improving diffusion of product olefin from the pores more rapidly, minimizing side reactions and coke formation.

We have demonstrated that the deposition of metals near the surface of the support particle can be effective for paraffin dehydrogenation catalyst advancements [7, 8, 12, 13]. Table 3 demonstrates the effectiveness of employing a thin layer Pt in heavy paraffin dehydrogenation.

Clearly, catalyst G with the shortest diffusion path in the Pt layer is the most selective and stable catalyst.

It is clear that mass transfer can play a role in paraffin dehydrogenation and that all three methodologies, or combinations thereof, can improve catalyst performance and the overall process economics.

2.4 Chemical Factors

Due to the combination of process with high temperature of operation and low pressure, the chemical composition of dehydrogenation catalysts is critical to avoid high carbon deposition and side reactions. The reaction of olefins on unmodified platinum is faster than that of paraffins because olefins interact with platinum more strongly than do paraffins. The role of platinum modifiers is to weaken the platinum–olefin interaction selectively without affecting the platinum–paraffin interaction. The modifier also improves the stability against coking by heavy carbonaceous materials. In previous studies, we have shown that modification of Pt improves catalyst selectivity and stability [15].

Theoretical work by Souflet and Weckhuysen has shown that the modifiers affect the Pt electron density to effectively weaken the Pt–olefin bonding by a combination of mechanisms [16, 17]. It has been shown that the addition of tin suppresses the formation of strongly adsorbed species, including di-s species and propylidene [18–25]. Zaera and Chrysostomou proposed that coke formation and cracking occur through these strongly adsorbed species on unmodified Pt [19].

Beyond providing porosity for mass transport, the catalyst support must provide the surface area to disperse noble metals and modifiers. Silica–Alumina, zeolites, aluminas, titanias, magnesium oxide, mixed oxide spinels and perovskite are suitable dehydrogenation support candidates. The need to eliminate acidity on the support is well-recognized [26].

UOP has commercialized many generations of propane and heavy paraffin dehydrogenation catalysts, which support further advancements in Oleflex™ and linear alkylbenzene detergent technology.

2.5 Oxidative Reheat in Ethylbenzene Dehydrogenation

The dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene (EB) to styrene monomer (SM) is a highly endothermic reaction. Conventional styrene units have two or more reaction stages, with steam reheat of the reaction mixture between stages. The Lummus/UOP SMART process employs an innovative catalytic oxidation technology to selectively “burn” the hydrogen liberated by the dehydrogenation of EB [27]. Selective oxidation of hydrogen provides direct and more efficient reheating of the reaction mixture, which reduces steam consumption (Fig. 1). The removal of hydrogen from the reaction mixture also shifts the reaction equilibrium towards production of SM, according to LeChatelier’s Principal. This shift in equilibrium dramatically increases single-pass EB conversion while maintaining high selectivity to SM. While both conventional SM technologies and the SMART process benefit from low-pressure operation, the removal of hydrogen from the reaction system makes the SMART process less sensitive to increased operating pressure.

In the SMART process, dilution steam is added to the injected oxygen (or air) to ensure that the reactor remains always outside the flammability envelope, regardless of how effectively this injected stream is mixed with the process fluid.

In conventional styrene units, selectivity and conversion are inversely related: as EB conversion increases selectivity to SM decreases and vice versa (Fig. 2). In order to achieve acceptable selectivity, conventional styrene units are usually operated at 65–67 % EB conversion per pass. By removing hydrogen and shifting the reaction equilibrium, SMART units can be operated at higher EB conversion while still maintaining high selectivity. Higher EB conversion in SMART means that less unconverted EB must be recycled, which results in lower capital cost and utility consumption per ton of SM product.

The challenge to be solved is to achieve maximum output from an existing asset through capacity expansion with minimal changes to existing, high-value equipment that is often difficult to replace. Converting an existing, conventional styrene unit to the SMART process can increase production capacity over 50 % without significant modifications to the existing steam superheater, heat recovery train, and fractionation section. The oxidative reheat feature eliminates the need to expand the capacity of the existing steam superheater to accommodate additional SM capacity. Figure 3 shows one process option for revamping an existing styrene plant by adding a SMART reactor with oxygen injection.

2.6 Oxidation Catalyst Design

The key to any oxidative reheat process is the selective oxidation catalyst, which must be able to selectively combust H2 without combusting or steam reforming ethylbenzene/styrene. The oxidation catalyst performance is important because the purpose is to deliver a reheated stream without any inhibitors or poisons to the next stage of dehydrogenation catalyst. The key oxidation catalyst requirements are:

-

100 % O2 Conversion

-

High Selectivity for H2 Combustion

-

Highly Stable without Regeneration

-

No effect on Pressure Drop

-

Equivalent Styrene Monomer Purity

The catalyst needs to completely convert all the oxygen added for reheating since unreacted oxygen can poison Fe–K styrene dehydrogenation catalysts. Selectivity for hydrogen combustion should be as high as possible, because both CO and CO2 have been reported to inhibit styrene dehydrogenation catalysts [28]. The stability needs to be at least equal to standard dehydrogenation catalysts, 18 months to 3 years, to avoid additional shutdowns. Of course, the ethylbenzene dehydrogenation equilibrium is very pressure sensitive, so minimizing pressure drop is critical and making styrene purity is a must.

The conditions in the ethylbenzene dehydrogenation process are severe: temperatures exceed 600 °C with >80 mol% steam. Thus, hydrothermal stability is a critical parameter for oxidation catalyst (OC). Table 4 shows the effect of calcinations temperature on OC performance.

Clearly, catalyst OC-3 in Table 4 shows superior activity and activity stability based on oxygen conversion and the ability to maintain the theoretical 60 °C temperature rise across the oxidation catalyst zone. All the catalysts demonstrated good selectivity at these conditions. After testing, characterization showed that both OC-1 and OC-2 had undergone some transformation in pore structure while OC-3 was stable.

Of course, the majority of the phase in OC-3 was alpha alumina and as such, the dispersion and maintenance of noble metal dispersion is a major factor in catalyst design. Through a series of inventions, we were able to demonstrate very high maintenance of Pt activity against severe hydrothermal aging as well as minimize diffusional limitations [29–34]. Figure 4 shows the pilot performance of advanced oxidation catalyst approaching 1 year on stream maintaining 100 % oxygen conversion with 92 % selectivity for the combustion of hydrogen.

3 Conclusion

Catalytic dehydrogenation continues to grow in importance for the production of olefins, especially with the availability of inexpensive light paraffin supplies. Dehydrogenation catalyst design incorporates the basic principles of catalysis, reducing diffusional resistance and providing a chemical composition, which is stable under the process conditions. The advancement and characterization of sub nanometer metal multi-metallic catalysts will be the subject of future contributions. The coupling of catalytic dehydrogenation with selective oxidation of hydrogen allows one to design a process, which greatly improves equilibrium ethylbenzene conversions while maintaining very high selectivity to styrene.

4 Experimental Section

Catalyst Preparation Catalysts were prepared according to US 4,717,781—Example I and US 4,786,625—Example II, US 5,233,118—Example I, and US 6,177,381—Example 6.

Testing Protocol The catalysts which were prepared according to the above examples were evaluated for conversion of ethylbenzene to styrene with regard to catalyst activity and selectivity for oxygen reacting with hydrogen to form water. The catalysts were loaded into a 7/8′′ inner diameter stainless steel reactor having a 10′′ long ½′′ diameter base for the catalyst loading. The reactor inlet temperature was adjusted to maintain a 600 or 630 °C maximum temperature and a feedstock comprising a mixture of ethylbenzene, styrene, steam, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, which simulated a product stream at about a 70 % ethylbenzene conversion from a second dehydrogenation catalyst bed of a three dehydrogenation catalyst bed reactor system having an oxidation catalyst bed position between the dehydrogenation catalyst beds was fed to the reactor. The feed stream was passed over the oxidation catalyst bed at an inlet temperature of 570 °C and at a reactor outlet pressure of 0.7 atmospheres (0.709 kPa). The hydrocarbon feed was maintained at a Weight Hourly Space Velocity of 34 −1. The molar feed ratio of ethylbenzene and styrene/H2O/H2/O2/N2 equaled 1.0/9/0.45/0.26/1.

References

Holmquist K (2010) Oil Gas J 108:27

Working Document of the National Petroleum Council North American Resource Development Study, Made Available September 15, 2011, Paper #1–13

Imai T, Abrevaya H, Bricker JC, Jan DY (1988) US 4,786,625, 22 Nov 1988

Imai T, Abrevaya H, Bricker JC, Jan DY (1989) US 4,827,072, 2 May 1989

Bricker JC, Jan DY, Foresman JM (1990) US 4,914,075, 3 April 1990

Bricker JC, Jan DY, Foresman JM (1993) US 5,233,118, 22, 3 Aug 1993

Jensen RH, Bricker JC, Chen Q, Tatsushima M, Kikuchi K, Takayama M, Hara K, Tsunokuma I, Serizawa H (2001) US 6,177,381, 23 Jan 2001

Jensen RH, Bricker JC, Chen Q, Tatsushima M, Kikuchi K, Takayama M, Hara K, Tsunokuma I, Serizawa H (2001) US 6,280,608, 28 Aug 2001

Chen JQ, Moscoso JG, Bricker JC, Cohn MJ (2008) US 7,432,406, 7 Oct 2008

Rende DE, Rekoske JE, Bricker JC, Boike JL, Takayama M, Hara K, Nobuyuki Aoi (2010) US 7,807,045, 5 Oct 2010

Vora BV Development of Platinum Catalysts for Paraffin Dehydrogenation. China/U.S. (2000) Joint Chemical Engineering Conference, 25–28 September 2000

Imai T, Abrevaya H (1989) US 4,880,764, 14 Nov 1989

Abrevaya H, Imai T (1991) US 5,012,027, 30 April 1991

Imai T, Vora BV, Bricker JC (1989) Development of dehydrogenation catalysts and processes. Petroleum and Petrochemical College, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, December 1989

Miguel SR, Scelza OA, Castro AA, Garcõ Fierro JLG, Soria J (1996) FTIR and XPS study of supported dehydrogenation. Catal Lett 36:201

Vigné F, Haubrich J, Loffreda D, Sautet P, Delbecq F (2010) J Catal 275:129–139

Iglesias-Juez A, Weckhuysen BM et al (2010) J Catal 276:268–279

Cortright RD, Dumesic JA (1994) J Catal 148:771

Zaera F, Chrysostomou D (2000) Surf Sci 457:89

Burnett DJ, Gabelnick AM, Marsh AL, Fischer DA, Gland JL (2004) Surf Sci 553:1

Fan Y, Xu Z, Zang J, Lin L (1991) Studies on the degradation in regeneration cycles. Stud Surf Sci Catal 683:68

Stacchiola D, Burkholder L, Tysoe WT (2003) Surf Sci 542:129

Cortright RD, Hill JM, Dumesic JA (2000) Catal Today 55:213

Sanfilippo D, Miracca I (2006) Dehydrogenation of paraffins: synergies between catalyst design and reactor engineering. Catal Today 111:133

Tsai Y-L (1997) Surf Sci 385:37

Bloch H (1972) UOP US 3,682,838, 1972

Rothenberg G, Catalysis:Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, ISBN 978-3-527-31824-7

Matsui J, Sodesawa T, Nozaki F (1990) Appl Catal 67(1):179–188

Bricker J, Imai T, Mackowiak D (1988) US 4,717,779, 5 Jan 1988

Bricker J (1987) US 4,691,071, 1 Sept 1987

Imai T, Bricker J (1987) US 4,652,687, 24 March 1987

Imai T, Bricker J (1989) US 4,812,597, 14 March 1989

O’Hara M, Imai T, Bricker J, Mackowiak D (1986) US 4,565,898, 21 Jan 1986

Woodle GB, Zarchy AS, JC Bricker, Ringwelski AZ (2005) US 6,858,769, 22 Feb 2005

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bricker, J.C. Advanced Catalytic Dehydrogenation Technologies for Production of Olefins. Top Catal 55, 1309–1314 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-012-9912-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-012-9912-1