Abstract

Patients receiving chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and concomitant low-dose aspirin (LDA) are at increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity. A fixed-dose combination of enteric-coated (EC) naproxen and immediate-release esomeprazole magnesium (NAP/ESO) has been designed to deliver a proton-pump inhibitor followed by an NSAID in a single tablet. To examine safety data from 5 Phase III studies of NAP/ESO in LDA users (≤325 mg daily, administered at any time during the study), and LDA non-users, data were analyzed from 6-month studies assessing NAP/ESO versus EC naproxen in patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis (n = 2), 3-month studies assessing NAP/ESO vs celecoxib or placebo in patients with knee osteoarthritis (n = 2), and a 12-month, open-label, safety study of NAP/ESO (n = 1). In an analysis of two studies, incidences of endoscopically confirmed gastric ulcers (GUs) and duodenal ulcers (DUs) were summarized by LDA subgroups. In the pooled analysis from all five studies, incidences of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) (including prespecified NSAID-associated upper GI AEs and cardiovascular AEs), serious AEs, and AE-related discontinuations were stratified by LDA subgroups. Overall, 2,317 patients received treatment; 1,157 patients received NAP/ESO and, of these, 298 received LDA. The cumulative incidence of GUs and DUs in the two studies with 6-month follow-up was lower for NAP/ESO vs EC naproxen in both LDA subgroups [GUs: 3.0 vs 27.9 %, respectively, for LDA users, 6.4 vs 22.4 %, respectively, for LDA non-users (both P < 0.001); DUs: 1.0 vs 5.8 % for LDA users, 0.6 vs 5.3 % for LDA non-users]. The incidence of erosive gastritis was lower in NAP/ESO- vs EC naproxen-treated patients for both LDA users [18.2 vs 36.5 %, respectively (P = 0.004)] and LDA non-users [19.8 vs 38.5 %, respectively (P < 0.001)]. Among LDA users, incidences of NSAID-associated upper GI AEs were: NAP/ESO, 16.1 %; EC naproxen, 31.7 %; celecoxib, 22.1 %; placebo, 23.2 %. Among LDA non-users, incidences of NSAID-associated upper GI AEs were: NAP/ESO, 20.3 %; EC naproxen, 36.6 %; celecoxib, 18.5 %; placebo, 18.9 %. For LDA users, incidences of cardiovascular AEs were: NAP/ESO, 3.0 %; EC naproxen, 1.0 %; celecoxib, 0 %; placebo, 0 %. For LDA non-users, incidences of cardiovascular AEs were: NAP/ESO, 1.0 %; EC naproxen, 0.6 %; celecoxib, 0.3 %; placebo, 0 %. NAP/ESO appears to be well-tolerated in patients receiving concomitant LDA. For LDA users, AE incidence was less than that observed for EC naproxen. For most AE categories, incidences were similar among NAP/ESO, celecoxib and placebo groups. The safety of NAP/ESO appeared similar regardless of LDA use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

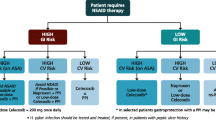

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used for managing the symptoms of many inflammatory conditions, including osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and other arthritic conditions. However, chronic NSAID therapy is associated with an increased risk of adverse gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular (CV) effects. For instance, chronic NSAID users develop endoscopic gastric ulcers (GUs) with point prevalences of 15–30 % [1], serious ulcer complications occur in about 2–4 % annually [1–4], and an increased incidence of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and congestive heart failure has also been reported with many NSAIDs [5, 6].

Among the known risk factors for CV toxicity with NSAID treatment are older age, hypertension, and established CV disease [7, 8]. Risk factors for NSAID-associated GI complications include older age, history of ulcers or upper GI (UGI) symptoms, and concomitant use of such medications as anticoagulants and low-dose aspirin (LDA) [9, 10]. Twenty percent of NSAID users are estimated to take concomitant LDA, usually as prophylaxis for CV events [11].

A recommended strategy to prevent higher risk patients from developing NSAID-associated ulcers is the concomitant administration of a gastroprotective agent, for example, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) [2, 12–16]. PPIs have also been shown to reduce the risk for GUs, duodenal ulcers (DUs), and their complications associated with the continuous use of LDA [17–19].

However, despite recommendations from guidelines, several studies suggest that, although increasing, use of concomitant gastroprotective agents with NSAIDs remains low [20–24].

As a potential solution to the under-use of gastroprotective agents, a fixed-dose combination of enteric-coated (EC) naproxen 500 mg and immediate-release (IR) esomeprazole magnesium 20 mg (naproxen/esomeprazole magnesium; NAP/ESO) has been designed to provide sequential delivery of, first, a PPI, and then an NSAID from a single tablet. Phase III trials have demonstrated comparable efficacy for NAP/ESO and celecoxib in the treatment of OA of the knee [25], while NAP/ESO was associated with a significantly lower incidence of endoscopic GUs compared with EC naproxen in patients at risk for developing NSAID-associated ulcers [26]. Furthermore, long-term (12-month) use of NAP/ESO was not associated with any new safety issues, including predefined UGI and CV adverse events (AEs) [27]. The NAP/ESO combination is currently licensed in both the United States and Europe for the relief of signs and symptoms of OA, RA, and ankylosing spondylitis, and to decrease the risk for developing NSAID-associated GUs in at-risk patients [28, 29].

The regulatory studies with the NAP/ESO combination tablet included a substantial number of patients who were also taking LDA, reflecting the frequency with which such dual NSAID/LDA therapy occurs in routine clinical practice. In order to explore the possible GI and CV effects of combining LDA with either the combination tablet or other NSAID, prespecified analyses of ulcer incidence in patients stratified by LDA use were conducted and AE data from all 5 Phase III studies were pooled in a post hoc analysis of the safety and tolerability of NAP/ESO.

Patients and methods

Studies

The study designs of the 5 Phase III studies included in this analysis have been reported previously [25–27]. Briefly, studies 301 (NCT00527787) and 302 (NCT01129011) were identically designed 6-month, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies comparing NAP/ESO and EC naproxen tablets in patients who were at risk of developing GUs [26]. The primary endpoint was the cumulative incidence of patients with endoscopically observed GUs (≥3 mm diameter with depth) at any time throughout the 6 months of treatment. Studies 307 (NCT00664560) and 309 (NCT00665431) were identically designed 3-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies comparing NAP/ESO, celecoxib, and placebo, whose primary aim was to assess efficacy in pain relief of these agents in patients with OA of the knee, using the Pain and Function Subscales of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) OA index and the patient global assessment of OA questionnaire [25]. Study 304 (NCT00527904) was a 12-month, open-label, multicenter study assessing the safety of NAP/ESO in patients with OA, RA, or other conditions requiring daily NSAIDs for at least 12 months and at risk of GI events [27]. For all studies, data were collected on treatment-emergent AEs, serious AEs (SAEs), AEs leading to discontinuation, and predefined NSAID-associated UGI AEs. In addition, studies 301, 302, 307, and 309 included an assessment of tolerability endpoints, such as heartburn resolution, severity of dyspepsia assessment (SODA) or modified SODA (mSODA), and rescue antacid use, while study 304 collected data on heartburn and dyspepsia as AEs, alongside exposure to, and dosage of, acetaminophen [25–27].

Patients

The five studies enrolled patients with OA, RA, ankylosing spondylitis, or another condition expected to require chronic daily NSAID therapy. Studies 307 and 309 included patients with OA of the knee only. Eligible patients were aged 50 years or over. In addition, studies 301, 302, and 304 also permitted younger patients (aged 18–49 years) provided they had a history of uncomplicated GU or DU within the previous 5 years. The use of LDA (defined as ≤325 mg/day) was allowed at the discretion of the treating physicians in all studies. Among the key exclusion criteria were uncontrolled or unstable cardiac disorder, prior GI disorder or surgery leading to impaired drug absorption, allergic reaction, or intolerance to any PPI or any NSAID (including aspirin). In the endoscopic studies (301 and 302), patients had to be ulcer-free at a baseline endoscopy.

Study treatment

In studies 301 and 302, patients received either oral NAP/ESO (EC naproxen 500 mg/IR esomeprazole 20 mg) twice daily or oral EC naproxen 500 mg twice daily. In study 304, patients received oral NAP/ESO twice daily as described for studies 301 and 302. In studies 307 and 309, patients received oral NAP/ESO twice daily, celecoxib 200 mg twice daily, or placebo.

Treatment was discontinued if patients withdrew informed consent, were judged by the investigator to be at significant safety risk, became pregnant, had a creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min, or had a confirmed decrease in hemoglobin level of >2.0 g/dL. In addition, in studies 301, 302, and 304, treatment was discontinued if patients developed an ulcer.

Incidence of ulcers

Studies 301 and 302 assessed GUs and DUs using endoscopy. Data from these two studies were pooled in a predefined analysis to assess the effect of NAP/ESO plus concomitant LDA use on the incidence of GUs and DUs.

Safety

AEs and SAEs occurring from the start of the study drug administration to the end of each study were recorded and coded using preferred terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 10.1. Overall, AE and SAE data were pooled across all five studies for all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug). For the purpose of comparing safety across all five studies, a data cut-off of 120 days was used for studies 301, 302, and 304. For consistency across the studies, AEs identified via endoscopy were excluded in this analysis.

CV events were prespecified in study 304 and were compiled by the sponsor’s physician and an independent cardiologist based on literature and medical expertise. This compilation was used for all the other studies. All CV AE data were pooled across all five studies and presented according to LDA users and non-users.

Statistical analyses

Overall, AE and SAE data were stratified by subgroups of LDA users and LDA non-users and pooled for post hoc analysis. Patients who were taking LDA at any time during the study period for a particular study were considered to be an LDA user. The incidence of an event refers to the proportion of patients who reported that event, and not the number of occurrences of that event.

A summary of the cumulative observed incidence of GUs and DUs at 1, 3, and 6 months was produced based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population in studies 301 and 302 (i.e., all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had no ulcer as detected by endoscopy at screening); however, the ITT and safety populations were identical in these two studies. Safety analyses were based on safety populations (all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug) in each study. The incidences of endoscopically observed GU and DU, and incidences of AEs of erosive gastritis and erosive duodenitis, were analyzed using pooled data from studies 301 and 302 for the prespecified subgroups of LDA users and LDA non-users.

The incidence of prespecified NSAID-associated UGI AEs (including dyspepsia, abdominal discomfort, gastritis, and vomiting; Table 1), and discontinuation rates due to any AE or a prespecified NSAID-associated UGI AE, were summarized by LDA subgroup in the pooled safety populations of all five studies.

In order to accurately compare the safety results across the treatment groups in the five studies, which had varying study lengths and AE identification methods (e.g., use or non-use of endoscopy), AEs starting >120 days after the first dose of study medication in studies 301, 302, and 304 were not included in these summaries, nor were AEs identified during an endoscopy in studies 301 and 302.

Statistical summaries were completed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 8.

Results

Patients

Overall, 2,317 patients were treated across the five studies, and 1,790 patients completed the studies (Fig. 1). Treatment arms within the individual studies were well-balanced and baseline demographics and characteristics were similar for patients within studies [25–27]. Table 2 shows the baseline demographics and patient characteristics by LDA subgroup. Across the five studies, 4.8 % of patients had a previous history of ulcer, while 55.7 % of patients had a previous history of CV events.

Patient disposition in the five studies. AE adverse event, DU duodenal ulcer, EC enteric-coated, FU follow-up, ITT intent-to-treat, mo month, mITT modified intent-to-treat, NAP/ESO naproxen/esomeprazole magnesium, naprox. naproxen, pop. population, S safety. *Patients completed 6 months of study treatment or discontinued due to gastric ulcer. †Patients completed ≥348 days on study treatment

Overall, 1,157 patients were treated with NAP/ESO. Of these, 298 were identified as taking concomitant LDA (≤325 mg/day) during the study (99 patients in studies 301 and 302 combined, 124 patients in studies 307 and 309 combined, and 75 patients in study 304). Of the 298 patients who were identified as taking NAP/ESO and concomitant LDA, an average daily LDA dose could be calculated for 292 patients. An LDA dose of ≤ 100 mg/day was received by 240 (80.5 %) of the NAP/ESO patients, while 52 (17.4 %) patients received a dose of 101–325 mg/day.

The average daily LDA dose could not be determined for 11 of the LDA users (n = 6 in the NAP/ESO group; n = 1 in the placebo group; n = 4 in the EC naproxen group); for these patients, the LDA dose was classified as either “dose not recorded” or “unable to determine”.

Of the patients who were determined to be LDA users, 3 patients (1 in the EC naproxen group of study 301, 1 in the EC naproxen group of study 302, and 1 in the NAP/ESO group of study 304) were originally classified as LDA non-users in the study-level analyses reported elsewhere, as the medication they were taking (Aggrenox or BC Powder) was not among the original LDA search terms. Two of these patients received an LDA dose of ≤100 mg/day, while the third had their LDA dosage classified as “other”.

The median durations of exposure to NAP/ESO were 178.5, 85, and 349 [27] days in the safety populations for studies 301 and 302 combined, 307 and 309 combined, and study 304, respectively.

Incidence of ulcers

The cumulative incidence of GUs at month 6 by LDA use subgroup in studies 301 and 302 has been published previously [26]. This publication reported that NAP/ESO was associated with a significantly lower incidence of GUs than EC naproxen, irrespective of concomitant LDA use (3.0 vs 28.4 %, respectively in LDA users and 6.4 vs 22.2 %, respectively in LDA non-users; P < 0.001 in favor of NAP/ESO in both subgroups) [26]. The reclassification of two patients’ LDA status for this analysis did not substantially alter these findings: incidence of GUs with NAP/ESO vs EC naproxen in LDA users was 3.0 vs 27.9 %, respectively, and incidence in LDA non-users was 6.4 vs 22.4 %, respectively.

Among LDA users, the cumulative observed incidences of GUs at 1, 3, and 6 months in NAP/ESO-treated patients were low and substantially less than those observed for EC naproxen-treated patients (Fig. 2); the cumulative observed incidences of DUs among patients receiving NAP/ESO and concomitant LDA were also low and less than those observed for EC naproxen-treated patients (Fig. 2). Similar trends in the incidence of GUs and DUs were observed in the LDA non-user group at 1, 3, and 6 months (Fig. 2).

Incidence of erosive gastritis and erosive duodenitis

Overall, erosive gastritis was reported as an AE in fewer NAP/ESO-treated patients than EC naproxen-treated patients [19.4 % (83/428) vs 38.0 % (162/426), pooled analysis of data from studies 301 and 302; Chi squared P < 0.001]. Among LDA users, the incidence of erosive gastritis was significantly higher in the EC naproxen group compared with the NAP/ESO group [36.5 % (38/104) vs 18.2 % (18/99); Chi squared P = 0.0046]. A similar finding was observed for incidence of erosive gastritis among LDA non-users [38.5 % (124/322) vs 19.8 % (65/329) for EC naproxen and NAP/ESO, respectively; Chi squared P < 0.001]. Of the patients who had erosive gastritis, 4 (0.9 %) patients in the NAP/ESO treatment group (all LDA non-users) and 39 (9.2 %) patients in the EC naproxen group (12 LDA users and 27 LDA non-users) also had a GU.

The incidence of erosive duodenitis was also lower among patients treated with NAP/ESO than those receiving EC naproxen [2.1 % (9/428) vs 11.7 % (50/426), pooled analysis in studies 301 and 302; Fisher’s exact P < 0.0001]. Among LDA users, the incidence of erosive duodenitis was lower for the NAP/ESO group than the EC naproxen group [2.0 % (2/99) vs 5.8 % (6/104)]. However, the test for differences was not significant (Fisher’s exact P = 0.28). Among LDA non-users, rates of erosive duodenitis were significantly lower for patients in the NAP/ESO group than the EC naproxen group [2.1 % (7/329) vs 13.7 % (44/322), respectively; Fisher’s exact P < 0.0001]. Only one patient across both studies experienced both erosive duodenitis and a DU (an EC naproxen-treated patient in the LDA non-user group).

Safety

Adverse events

Among LDA users across all 5 studies, the incidence of reported AEs was similar across all treatment groups; 56.0 % (167/298) of NAP/ESO-treated patients reported AEs compared with 58.7 % (61/104) of EC naproxen-treated patients, 53.8 % (56/104) of celecoxib-treated patients, and 57.1 % (32/56) of placebo-treated patients. Among LDA non-users, the corresponding incidences were also similar across treatment groups: 54.9 % (472/859) for NAP/ESO; 59.6 % (192/322) for EC naproxen; 48.4 % (186/384) for celecoxib; and 49.5 % (94/190) for placebo (Table 3). GI disorders were the most commonly reported AEs in patients treated with NAP/ESO; the most common GI AE was dyspepsia (Table 3).

Among LDA users, the incidences of prespecified NSAID-associated UGI AEs were lowest for NAP/ESO [16.1 % (48/298)], highest for EC naproxen [31.7 % (33/104)], and were 22.1 % (23/104) for celecoxib, and 23.2 % (13/56) for placebo. The difference between NAP/ESO and EC naproxen was statistically significant (Chi squared test, P = 0.001). The most common prespecified NSAID-associated UGI AEs were dyspepsia, nausea, and upper abdominal pain (Table 4). Among LDA non-users, prespecified NSAID-associated UGI AEs were observed in 20.3 % (174/859) of NAP/ESO-treated patients, 36.6 % (118/322) of EC naproxen-treated patients (the highest incidence amongst the treatments considered), 18.5 % (71/384) of celecoxib-treated patients, and 18.9 % (36/190) of patients receiving placebo (Table 4). Again, the difference between NAP/ESO and EC naproxen was statistically significant (Chi squared test, P < 0.001).

Among LDA users, CV AEs occurred in 3.0 % (9/298) of NAP/ESO-treated patients compared with 1.0 % (1/104), 0 % and 0 % of patients receiving EC naproxen, celecoxib, and placebo, respectively; cardiovascular disorders that occurred in two or more patients were coronary artery disease and palpitations (Table 5). One NAP/ESO-treated patient who was in the LDA user subgroup experienced atrial fibrillation, which was classified as mild. For LDA non-users, CV AEs were reported for 1.0 % (9/859) of NAP/ESO-treated patients compared with 0.6 % (2/322), 0.3 % (1/384), and 0 % of patients receiving EC naproxen, celecoxib, and placebo, respectively; CV disorders that occurred in two or more patients were palpitations and cardiomegaly (Table 5). One NAP/ESO-treated patient in the LDA non-user group had an SAE of peri-operative MI. This serious CV event, which occurred 6 days after the patient was hospitalized for unstable angina, subsequently resolved, and was assessed by the investigator as being unrelated to NAP/ESO use.

The overall incidences of SAEs among LDA users across the five pooled studies were 2.7 % (8/298) in NAP/ESO-treated patients, 2.9 % (3/104) in EC naproxen-treated patients, 4.8 % (5/104) in celecoxib-treated patients, and 0.0 % in placebo-treated patients (Table 6). Among LDA non-users, the overall incidences of SAEs were 1.7 % (15/859) in NAP/ESO-treated patients, 1.2 % (4/322) in EC naproxen-treated patients, 0.8 % (3/384) in celecoxib-treated patients, and 0.5 % (1/190) in placebo-treated patients (Table 6). No preferred term SAE occurred in more than one patient.

Discontinuations

Among LDA users, discontinuations due to any AE were reported in 9.1 % (27/298), 13.5 % (14/104), 9.6 % (10/104), and 5.4 % (3/56) of patients receiving NAP/ESO, EC naproxen, celecoxib, and placebo, respectively; corresponding discontinuations due to any AE among LDA non-users were 7.7 % (66/859), 7.8 % (25/322), 7.3 % (28/384), and 4.7 % (9/190), respectively. The most common AE category leading to discontinuation, irrespective of LDA subgroup, was GI disorders.

Of the predefined NSAID-associated UGI AEs leading to discontinuation in LDA users, the most commonly reported (occurring in ≥2 % of patients in any treatment group) was dyspepsia [NAP/ESO, 0.3 % (1/298); EC naproxen, 3.8 % (4/104); celecoxib, 1.0 % (1/104); placebo, 0 % (0/56)]. Among LDA non-users, the most frequently reported (occurring in ≥2 % of patients in any treatment group) predefined NSAID-associated UGI AE leading to discontinuation was also dyspepsia [NAP/ESO, 0.7 % (6/859); EC naproxen, 2.2 % (7/322); celecoxib, 0.8 % (3/384); placebo, 1.1 % (2/190)]. For both LDA categories, EC naproxen had the highest rate of discontinuations.

Discussion

Patients who take traditional NSAIDs or COX-selective NSAIDs are at increased risk for UGI complications and ulcers if they also take LDA. The evidence has come from population studies and randomized trials where LDA consumption has been documented but not part of a formal randomization schema [3, 30–32], as well as from one study where all patients were given LDA and randomized to take naproxen, celecoxib, or placebo in addition [33]. This result is hardly surprising, as LDA is an NSAID, and combining LDA with another NSAID effectively increases the total NSAID dose.

The aim of this present analysis was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a fixed-dose combination of NAP/ESO in patients taking concomitant LDA, using pooled data from 5 previously published Phase III studies in which GI AEs were prespecified outcomes.

One of the main findings from the two endoscopic studies is that NAP/ESO-treated patients were substantially less likely than those taking EC naproxen to develop either a GU or a DU, irrespective of whether they were taking LDA or not. The difference was evident at each of the three endoscopic-exam time points (months 1, 3, and 6). This is important information for treating clinicians.

Interestingly, there was a trend in the NAP/ESO group for those taking LDA to be less likely to have a GU at each of months 1, 3, and 6 than those not taking it. However, it is important to remember that patients were not randomized to take or not take LDA, which is why we have not performed statistical tests for those direct comparisons. Statistical testing has been confined to those comparisons where patients were randomly allocated to treatments. As expected, those who were randomized to naproxen without esomeprazole showed a trend to being more likely to develop ulcers if they also took LDA.

The observation from studies 301 and 302 that erosive gastritis and duodenitis (reported as an AE in those endoscopic studies) were also much less frequent with NAP/ESO than with EC naproxen parallels the ulcer frequency findings. Gastric and duodenal erosions are the precursor lesions for ulcers [34, 35], and treatment with PPIs is known to reduce the frequency of both erosions and ulcers in patients taking NSAIDs [36, 37].

Some of the results from studies 301 and 302 have been reported previously by Goldstein et al. [26]. The main additional findings presented here are the lower frequencies of DUs and gastroduodenal erosions in the patients who received the NAP/ESO formulation, and the analysis of the data according to whether LDA was also taken.

Previous studies have shown that PPIs protect against ulcer development in patients taking either NSAIDs or LDA separately [12, 13], but they have also been found to be protective against the combination [38]. Our current findings are in agreement with this.

The pooled analysis of the five studies included an examination of the combined frequencies of the prespecified UGI AEs. As was the case for ulcers and erosions, these UGI AEs were substantially less common in patients randomized to take NAP/ESO than EC naproxen—further evidence for an advantageous safety profile of the combination formulation compared to the NSAID taken alone. As with GUs and DUs, this effect was seen whether or not the patients were taking LDA. Discontinuation rates due to an AE among patients receiving NAP/ESO were also similar in LDA users and non-users.

Cardiovascular AEs are of interest because of the concern that NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, as a family, predispose to a modest increase in thrombotic cardio- and cerebro-vascular events [13]. There is evidence that naproxen may be at the safer end of the NSAID/COX-2 inhibitor spectrum for producing CV events [9]. It has been suggested that this may be due to a fairly prolonged antiplatelet effect because of its long plasma half-life, although dedicated mechanistic studies are warranted to support this hypothesis [9, 39].

Our pooled analysis did not have sufficient statistical power to be able to make a contribution to understanding the relative CV safety of the four drugs tested, but some mostly reassuring conclusions can be reached. Across all five studies, only one serious CV event occurred (in a patient taking NAP/ESO who was not taking LDA). There was a slightly higher proportion of CV AEs and SAEs in patients taking LDA: this is not unexpected, since being treated with LDA was likely to be a reflection of being already at increased CV risk.

Study limitations

There are a number of potential limitations of this study. These include: (1) pooling of data from trials of different durations and with different comparators; (2) the comparison of data in patients taking or not taking LDA is potentially confounded by the fact that patients were not allocated randomly to this treatment; and (3) the potential for bias that can occur in any pooled analysis. Further, it was not possible to pool data for incidence of GUs and DUs from more than two of the studies, since the others did not include scheduled endoscopies.

Conclusions

The likelihood of developing GUs or DUs, as well as other UGI AEs such as bleeding, is higher if LDA is combined with an NSAID; however, the addition of a PPI reduces this risk. The findings of this analysis suggest that NAP/ESO therapy appears to be well-tolerated in patients regardless of concomitant LDA use, and offers significant protection against UGI ulcers, erosions and symptoms compared with EC naproxen alone. The combination therapy may be expected to increase compliance compared with prescription of the PPI and the NSAID separately. There were no clinically notable differences in the NAP/ESO safety profiles seen in LDA users and LDA non-users in this analysis, although it was not possible to determine the CV safety among patients at high risk for ischemic or thrombotic events. Prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm these findings.

References

Laine L (2001) Approaches to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the high-risk patient. Gastroenterology 120:594–606

Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EMM (2009) Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol 104:728–738

Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL et al (2000) Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib long-term arthritis safety study. JAMA 284:1247–1255

Fries JF, Williams CA, Bloch DA, Michel BA (1991) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor models. Am J Med 91:213–222

Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ et al (2008) Subgroup analyses to determine cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and coxibs in specific patient groups. Arthritis Rheum 59:1097–1104

Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S et al (2011) Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 342:c7086

Roth SH, Anderson S (2011) The NSAID dilemma: managing osteoarthritis in high-risk patients. Phys Sportsmed 39:62–74

Scheiman JM, Hindley CE (2010) Strategies to optimize treatment with NSAIDs in patients at risk for gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse events. Clin Ther 32:667–677

Rostom A, Moayyedi P, Hunt R (2009) Canadian consensus guidelines on long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 29:481–496

Serrano P, Lanas A, Arroyo MT, Ferreira IJ (2002) Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low-dose aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 16:1945–1953

Kim C, Beckles GL (2004) Cardiovascular disease risk reduction in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Prev Med 27:1–7

Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS et al (2008) ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 Expert Consensus Document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 118:1894–1909

Chan FKL, Abraham NS, Scheiman JM, Laine L (2008) Management of patients on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a clinical practice recommendation from the first international working party on gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and anti-platelet agents. Am J Gastroenterol 103:2908–2918

Desai SP, Solomon DH, Abramson SP et al (2008) Recommendations for use of selective and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an American College of Rheumatology white paper. Arthritis Rheum 59:1058–1073

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Osteoarthritis: the care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. NICE clinical guideline 59, 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG59NICEguideline.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2013

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al (2008) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartilage 16:137–162

Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J et al (2008) Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol 103:2465–2473

Yeomans ND (2011) Reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers with a fixed combination of esomeprazole and low-dose acetyl salicylic acid. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:447–455

Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM et al (2002) Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med 346:2033–2038

Abraham NS, El-Serag HB, Johnson ML et al (2005) National adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology 129:1171–1178

Goldstein JL, Howard KB, Walton SM et al (2006) Impact of adherence to concomitant gastroprotective therapy on nonsteroidal-related gastroduodenal ulcer complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1337–1345

Sturkenboom MCJM, Burke TA, Tangelder MJD et al (2003) Adherence to proton pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists during the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18:1137–1147

Sturkenboom MCJM, Burke TA, Dieleman JP et al (2003) Underutilization of preventive strategies in patients receiving NSAIDs. Rheumatology (Oxford) 42(Suppl 3):iii23–iii31

van Soest EM, Sturkenboom MCJM, Dieleman JP et al (2007) Adherence to gastroprotection and the risk of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal ulcers and haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 26:265–275

Hochberg MC, Fort JG, Svensson O et al (2011) Fixed-dose combination of enteric-coated naproxen and immediate-release esomeprazole has comparable efficacy to celecoxib for knee osteoarthritis: two randomized trials. Curr Med Res Opin 27:1243–1253

Goldstein JL, Hochberg MC, Fort JG et al (2010) Clinical trial: the incidence of NSAID-associated endoscopic gastric ulcers in patients treated with PN 400 (naproxen plus esomeprazole magnesium) vs. enteric-coated naproxen alone. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 32:401–413

Sostek MB, Fort JG, Estborn L, Vikman K (2011) Long-term safety of naproxen and esomeprazole magnesium fixed-dose combination: phase III study in patients at risk for NSAID-associated gastric ulcers. Curr Med Res Opin 27:847–854

European Medicines Compendium UK. Vimovo™, 2012. www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/23883/SPC/VIMOVO+500+mg+20+mg+modified-release-tablets/. Accessed 7 June 2012

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). VIMOVO™ prescribing information, 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022511lbl.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2012

Singh G, Fort JG, Goldstein JL et al (2006) Celecoxib versus naproxen and diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients: SUCCESS-I Study. Am J Med 119:255–266

Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT et al (2006) Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinations. Gut 55:1731–1738

Laine L, Smith R, Min K et al (2006) Systematic review: the lower gastrointestinal adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24:751–767

Goldstein JL, Lowry SC, Lanza FL et al (2006) The impact of low-dose aspirin on endoscopic gastric and duodenal ulcer rates in users of a non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or a cyclo-oxygenase-2-selective inhibitor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 23:1489–1498

Yeomans ND, Naesdal J (2008) Systematic review: ulcer definition in NSAID ulcer prevention trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:465–472

Hawkey CJ, Wilson I, Naesdal J et al (2002) Influence of sex and Helicobacter pylori on development and healing of gastroduodenal lesions in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users. Gut 51:344–350

Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepanski L et al (1998) Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med 338:727–734

Scheiman JM, Behler EM, Loeffler KM, Elta GH (1994) Omeprazole ameliorates aspirin-induced gastroduodenal injury. Dig Dis Sci 39:97–103

Goldstein JL, Huang B, Amer F, Christopoulos NG (2004) Ulcer recurrence in high-risk patients receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs plus low-dose aspirin: results of a post hoc subanalysis. Clin Ther 26:1637–1643

Capone ML, Tacconelli S, Sciulli MG et al (2004) Clinical pharmacology of platelet, monocyte, and vascular cyclooxygenase inhibition by naproxen and low-dose aspirin in healthy subjects. Circulation 109:1468–1471

Acknowledgments

These studies were sponsored and conducted by POZEN Inc. Lisa Suchower of AstraZeneca provided assistance in the statistical analysis of the data. Medical writing support was provided by Rhian Harper Owen, on behalf of Complete Medical Communications, funded by AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest

Neville D. Yeomans has previously consulted for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Merck and Glaxo, but has no current financial involvement with any pharmaceutical company. Dominick J. Angiolillo has received consulting fees or honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, AstraZeneca, Merck, Evolva, Abbott Vascular and PLx Pharma, and has received fees for review activities from Johnson & Johnson, St. Jude, and Sunovion. He has also received institutional grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, AstraZeneca, Evolva, and has other financial relationships with the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program. Shane Raines and Catherine Datto are employees of AstraZeneca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Angiolillo, D.J., Datto, C., Raines, S. et al. Impact of concomitant low-dose aspirin on the safety and tolerability of naproxen and esomeprazole magnesium delayed-release tablets in patients requiring chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy: an analysis from 5 Phase III studies. J Thromb Thrombolysis 38, 11–23 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-013-1035-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-013-1035-4