Abstract

This study explores the complexity of emotionally engaging schoolwork among students by analysing the interrelation between the affective and the social dimensions of emotional engagement. The data were collected from 78 Finnish sixth-grade (aged 12–13 years) and 89 eighth-grade (aged 14–15 years) students using picture tasks. The results show that the main elements of the affective dimension are the valuing of schoolwork and the enjoyment of learning, and the main element of the social dimension is a sense of belonging in terms of social cohesion and the support experienced by students. Furthermore, the results suggest that emotional engagement has internal dynamics: the affective and social dimension influence each other, regulating the students’ sense of emotional engagement. Consequently, neither of the dimensions alone result in strong, balanced emotional engagement. In addition, the results show that the relation between the affective and social dimension was more unbalanced in the peer interaction than in the teacher–student interaction at both grade levels. This suggests that tensions in the peer interaction at school make for a more complicated context in terms of emotional engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has been suggested that emotional engagement in school activities is a substantial prerequisite for students’ effort, achievement and persistence in studying (Audas and Willms 2001; Finn 1993; Fredricks et al. 2004; Janosz et al. 2000; Libbey 2004; Willms 2003). Students who regard school as vital and valuable and consider themselves to be members of the school community have been found to receive higher grades and to complete school successfully (Finn 1993; Finn and Voelkl 1993). Moreover, a strong sense of belonging at school is related to positive future orientations in adolescence (Crespo et al. 2013; Israelashvili 1997) and good overall development in adolescence (Debnam et al. 2014). In turn, students who do not feel themselves to be members of the school community and have negative perceptions of school are at risk of a wide range of long-term adverse consequences, such as disruptive classroom behaviour, absenteeism, and dropping out of school (Finn and Voelkl 1993; Harel-Fisch et al. 2011).

Moreover, disengagement from school may be reflected in the students’ ability to participate in the surrounding community and may increase the risk of social exclusion. Thus, concern over weak school engagement is related to learning outcomes and to adolescents’ ability to participate in social life and become members of society, and is thus understood to relate to students’ general wellbeing (Bond et al. 2007; Fredricks et al. 2004; Klasen 1999; Phillips-Howard et al. 2010). Even though most students engage with school successfully, negative attitudes towards schoolwork are quite common among students in many countries (Ikeda 2013) and problems in engaging with schoolwork tend to increase throughout the school career (Archambault et al. 2009; Li and Lerner 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2006). A low level of students’ emotional engagement is a reality also in Finland. Despite Finland’s PISA (the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment) success academically, the country was ranked 34 out of 39 countries based on students’ satisfaction at school (Ramelow et al. 2012). Problems are apparent in both social interactions in schools, for example, the school climate (Salmela-Aro et al. 2008), and in the valuing of schoolwork. For example, the study from Salmela-Aro et al. (in press) showed that almost half of the primary school students (age 12, n = 759) participating in the study did not see school as significant in their lives. A reason for the decreased level of student engagement is an increasing gap with adolescents’ life experiences and meaningful learning outside of school versus school practices (Salmela-Aro et al. in press).

Research on emotional engagement has focused heavily on the external or environmental factors that influence increased or hindered emotional engagement (Elffers et al. 2012; Gonida et al. 2009; Lee 2012; Li et al. 2010; Li and Lerner 2013; Wang et al. 2011). Prior studies have identified individual factors—such as the students’ background (Elffers et al. 2012; Gonida et al. 2009), mastery of goal orientation, and institutional characteristics, such as school goal structure (Gonida et al. 2009)—as having a significant impact on students’ emotional engagement. However, understanding of the internal dynamics of emotional engagement is still insufficient. This study aims to produce a better understanding of the nature of emotional engagement in schoolwork, which entails both students’ affects towards studying, valuing schoolwork and their sense of belonging in the school community (Archambault et al. 2009; Voelkl 1997; Wang et al. 2011).

2 Emotional engagement as a constituent of academic engagement

Academic engagement refers to students’ active involvement in school-related tasks, i.e. the studying and learning activities provided by the school community (Fredricks et al. 2004; Skinner et al. 2009). It is a multidimensional construct consisting of behavioural, cognitive and emotional components. Behavioural engagement entails active participation and involvement in studying and learning, whereas cognitive engagement refers to the student’s personal investment in learning activities, including self-regulation and a commitment to the mastery of learning (Fredricks et al. 2004). Emotional engagement, on the other hand, encompasses, for example, attitudes towards schoolwork and affects related to studying—such as enjoyment, anxiety or boredom—and school-related beliefs and a sense of belonging (Archambault et al. 2009; Fredrickson 2001).

Although the emotional, behavioural and cognitive components of academic engagement are often explored separately, they mutually influence each other over time. It has been suggested that emotional engagement plays a significant and distinctive role in the ways in which students engage in academic activities as their school career progresses (Li and Lerner 2013). In addition, it has been shown that students who feel a part of the school community and consider their schoolwork to be significant are more likely to employ effort, attention and persistence when initiating and sustaining learning activities, thus demonstrating the role of behavioural engagement (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Li et al. 2010; Li and Lerner 2013). In turn, a lack of interest has been found to be a central predictor of student drop-out (Mäkinen et al. 2004).

The experience of emotional engagement enhances students’ cognitive engagement (Li and Lerner 2013). For example, there is evidence that positive affects are associated with the use of more effective learning strategies, such as self-regulated learning and increased creativity, which further reflect positively on academic progress (Fredrickson 2001; Ketonen and Lonka 2013; Trigwell et al. 2012). Students’ sense of belonging has also been associated with the use of deep processing learning strategies (Dupont et al. 2014), such as relating ideas and concepts to each other. In turn, social exclusion has been found to reduce the use of higher-order processing (Baumeister et al. 2002). Students’ affects towards schoolwork and their experience of belonging to the school community is also reflected in their emotional wellbeing and psychological development (Wentzel 1998).

3 Affects and a sense of belonging in schoolwork

Prior studies on emotional engagement range from exploring students’ emotional reactions in the school environment (Gonida et al. 2009; Wellborn and Connell 1987) and students’ valuing of schoolwork to the sense of belonging experienced by students in the school community (Elffers et al. 2012; Finn 1993; Fredricks et al. 2004; Voelkl 1997; Wang et al. 2011). Affects refer to students’ intense, short-lived active states that arise in response to a particular situation or object of activity in school (Do and Schallert 2004). Affects such as enjoyment, curiosity, boredom, anxiety, and anger (Gonida et al. 2009) may vary during a single school day. Valuing schoolwork, on the other hand, refers to students’ interest and beliefs in the importance and relevance of the general goals of education and academic achievement (Wang et al. 2011), so it is more stable over time. The affects towards and valuing of the schoolwork are here viewed as the affective dimension of emotional engagement (Archambault et al. 2009). Respectively, a sense of belonging in terms of the school’s social contexts represents the social dimension of the emotional engagement, referring to the extent to which adolescents experience being personally accepted, respected, and supported by adults and peers in the school community (Finn 1989; Goodenow and Grady 1993; Ma 2003). Prior research shows that the need for positive and supportive relationships with peers and non-parental adults increases in adolescence (Elkind 1967; Nicholls 1990). In school, students’ key relationships are with teachers and their peers, contributing to students’ self-knowledge and affecting perceptions of how valuable and accepted they are (Wentzel 1998). Consequently, emotional engagement—especially in terms of schoolwork—results from the interaction between the student and the school environment (Fredricks et al. 2004). In this process, students simultaneously negotiate their social position, construct their relationships in the school community, and form their perceptions of the significance of schoolwork in interaction with their teachers and peers (Ulmanen et al. 2014). Accordingly, in the school context, the affective and social dimensions of emotional engagement are inherently intertwined.

There is evidence that a strong sense of belonging is likely to be fostered in a caring and supportive school environment (Battistich et al. 1997). Teachers play a specific role in ensuring students’ sense of belonging (Roeser et al. 1996). For example, teachers’ support—including teachers’ sensitivity, interest in students’ development, their way of regarding students’ perspectives, and the quality of their feedback, such as treating students’ respectively and fairly—has been found to be relevant in promoting students’ sense of belonging (Hoffman et al. 2002; Lee 2012; Roeser et al. 1996). Conversely, a lack of teacher support and constructive feedback have been related to a reduced level of belonging (Anderman and Anderman 1999). Teachers are responsible not only for constructing emotionally engaging teacher–student relations, but also for supporting functional peer interaction. Teacher’s intentions to promote mutual respect among classmates have been found to improve the sense of belonging among middle school students (Anderman 2003). In addition, the experience of peer support and a good classroom climate have been found to relate to a sense of belonging (Elffers et al. 2012; Hoffman et al. 2002).

There is some evidence that the constituents of emotional engagement have a reciprocal relationship (Goodenow and Grady 1993). For example, experiencing belonging in school regulates students’ perceptions of themselves as learners and as members of their school community, which further influences their involvement in schoolwork (Eccles and Roeser 2011; Furrer and Skinner 2003). An extensive body of research also shows that experiencing a sense of belonging in the teacher–student interaction is associated directly with students’ affects towards and valuing of the schoolwork (Anderson et al. 2004; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Klem and Connell 2004; Lee 2012; Patrick et al. 2007; Roeser et al. 1996). However, evidence is contradictory on whether and under what conditions a sense of belonging in peer relations contributes to students’ involvement in schoolwork. Close relationships with peers have been found to support students’ emotional engagement in schoolwork (Furrer and Skinner 2003). However, study burnout (Kiuru et al. 2008) and negative behaviours have also been found to be transmitted and hence to accumulate in close relationships (Sage and Kindermann 1999). Peers are a significant source of interpersonal and informational support (Martin and Dowson 2009; Wentzel 1998); however, it is not only the quality of the relationships, but also the content of interactions, such as shared experiences, knowledge and the object of activity, that affect students’ academic engagement (Martin and Dowson 2009; You 2011). Students are likely to share the same beliefs and values as their classmates (Berndt et al. 1999; Hallinan and Williams 1990). These beliefs and values do not always promote emotional engagement; they can also challenge students’ emotional engagement in schoolwork. For example, the authors of this study (2014) showed that conforming to the attitudes of the peer group often reduced students’ engagement in schoolwork. Moreover, secondary school students tended to engage in schoolwork primarily by navigating between their own academic values and the attitudes of the school environment. Students also avoided taking personal risks in peer interaction, especially in the higher grades (Ulmanen et al. 2014). However, our understanding of what this means in terms of students’ emotional engagement in schoolwork is still unclear.

4 Aim of the study

The aim of the study is to understand the complexity of emotionally engaging schoolwork among students in compulsory education. We explore the interrelation between the two main constituents of emotional engagement, i.e. the affective and the social dimension in the school’s everyday life. Furthermore, we analyse the dynamics between these two dimensions, both in the teacher–student interaction and in the peer interaction. Accordingly, we address the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the key elements of the affective dimension that contribute to an emotionally engaging experience?

-

2.

What are the key elements of the social dimension that contribute to an emotionally engaging experience?

-

3.

How are the affective and the social dimension intertwined in the teacher–student interaction and in the peer interaction?

-

4.

How do the experiences of sixth and eighth graders students differ from each other in terms of emotional engagement in academic activities?

5 Method

5.1 Participants

This study comprises data collected in Finland from the students of three compulsory comprehensive schools. One of the schools is a primary school that includes grades 1–6, while the other two schools include both primary and secondary levels, covering grades 1–9. (Also in the 1–9 grade schools, students go through a transition when they enter the secondary level; for example, their classmates and teachers change.) The schools are very typical Finnish schools situated in suburban areas. The student population of the selected schools varied from 345 to 650 students. All the sixth- (78) and eighth-grade (89) pupils from the case schools participated, comprising a total of 167 pupils (girls 54 %; boys 46 %). The reason for selecting sixth- (aged 12–13) and eighth-graders (aged 14–15) was the variation between the primary and secondary school characteristics. In Finland, compulsory comprehensive school includes the primary (grades 1–6) and secondary school (7–9) grades, which partly differ in terms of the organisation of the school day and subject teaching. In secondary schools, the diversity of teacher–student relationships and peer relationships increases due to the greater number of subjects taught by subject teachers. Hence, the complexity of the school’s social and pedagogical environment and the students’ choices related to the studying of different subjects increases in the upper grades of the comprehensive school (Sahlberg 2011). We received consent from the chief officers of the school districts, the schools, and the students and their parents for participation in the study.

5.2 Data collection and picture tasks

We collected the data using qualitative picture tasks developed and piloted by the research group. The students wrote stories based on four pictures situated in a school environment (see Fig. 1). The pictures were complemented with the following questions:

-

1.

What is happening at the moment?

-

2.

What has led up to the event shown?

-

3.

What is the student(s) thinking?

-

4.

What is the teacher thinking?

-

5.

What will happen next?

Accordingly, the students composed four episodes on the basis of the pictures (n = 277) related to the meaningful positive or negative situations that occur and are situated in formal and informal events at the schools.

The picture tasks were undertaken during the school day by researchers in the spring of 2011. Participation in the study was voluntary; students received no extra credits for participating. The reflective technique used is based on the assumption that students project their unfiltered perceptions, school-related affections, and desires onto neutral images (Branthwaite 2002), and that the pictures and questions help the students to project their school experiences and perceptions of the school environment. Therefore, the students interpret pictures in accordance with their own past experiences and current motivations (Porr et al. 2011).

5.3 Analysis

The data were qualitatively content-analysed (Mayring 2000). Our analytical strategy was compatible with the idea of a hermeneutic circle, which involves continuous interaction between the data and the development of a theoretical understanding of the key learning experiences (Coffey and Atkinson 1996). We evaluated emotional engagement by examining the affective dimension and the social dimension in two different contexts, namely in peer interaction and in teacher–student interaction. In the first phase of the analysis, episodes that projected the affective dimension and the social dimension in peer and/or teacher–student interaction were identified. Those episodes included students’ positive or negative affects towards schoolwork and/or valuing of schoolwork, and a strong or weak sense of belonging to the school’s social environment, e.g. a sense of being accepted, valued, included, and encouraged by others. These two dimensions of emotional engagement were further categorised into the categories ‘high’ and ‘low’. The category ‘low’ indicates a weak sense of belonging or negative affective reactions towards schoolwork. Correspondingly, the category ‘high’ describes a high sense of belonging and positive affective reactions towards schoolwork. A visualisation of the analytical process is presented in Fig. 1.

In the second phase of the analysis the profiles in terms of the described affections and sense of belonging that contributed to students’ emotional engagement or alienation were derived. We identified all combinations of low and high categories in terms of the affective and the social dimension in both teacher–student relationships and peer relationships. Finally, we identified the differences between the primary and the secondary school students’ episodes in terms of the affective and social dimension.

6 Results

6.1 Students’ emotional engagement

Students’ descriptions of emotionally engaging episodes entailed both positive affects towards studying at school and a sense of being an acknowledged member of the school community. As expected, the affects towards schoolwork ranged from very positive to very negative. Enjoyment of learning and valuing of schoolwork, both in the teacher–student and peer interactions, were identified as core constituents of the affective dimension of the emotional engagement in schoolwork. Positive affections, such as enthusiasm, excitement and enjoyment, were connected to the students’ perceptions of meaningful and inspiring learning in school. Conversely, feelings of frustration and boredom were connected to alienation from schoolwork and increased off-task behaviour in classes, i.e. reduced levels of emotional engagement in academic activities.

1) The pupils are working on their Finnish exercises. The classroom is quiet, everyone’s working peacefully. Only one pupil raises his/her hand to ask for help. 2) The Finnish teacher asked the pupils to write an essay about “Waiting for the summer”. 3) The pupils are writing the essay enthusiastically and in quiet concentration because they like the topic. It fits the moment, as everyone’s really looking forward to the summer. 4) The teacher is happy with the way the pupils are working and is eager to read their essays. 5) The bell rings and interrupts a good lesson; the pupils must finish their essays at home. Then the teacher will grade the essays as usual. The essay topic gets the pupils talking about summer during the break. (8th grader, picture 3)

Students also offered in-depth projections of the complexity of being an acknowledged actor in the school community. Emotional and informational support received from teachers and peers and social cohesion constructed with teachers and peers were the main constituents of the students’ sense of belonging. Students emphasised that received emotional support from teachers or peers—i.e. providing empathy, showing trust and encouraging each other—and the teachers’ capacity to align pedagogical practices with the students’ interests, motivations and skills contributed to the sense of being an acknowledged actor in the school community. The teachers’ and peers’ willingness to share knowledge and provide advice and guidance related to the school’s everyday activities (i.e. informational support) were also considered crucial to a sense of belonging in the school community. Moreover, emotionally warm relations resulting in the experience of connectedness (social cohesion) between students, and the teachers’ ways of promoting mutual respect among students, which contributed to the classroom climate, were greatly emphasised in the experience of emotional engagement at school.

1) The pupils don’t understand the teacher’s question, and the teacher tries to explain it. 2) The pupils are working in groups on an exercise given by their teacher. Then they run into a question they don’t understand. 3) It’s a difficult question, and they don’t understand it. The teacher’s explanations don’t make any sense. They don’t understand what the teacher is trying to say. Soon s/he will probably start yelling at us because we don’t understand him/her. 4) The teacher tries to remain patient and explain the matter in many different simple ways to make the pupils finally understand it. 5) In the end, one of the pupils understands what the teacher is trying to say and explains it to the others so that they can understand it too. (8th grader, picture 4)

1) The group includes a pupil who’s usually an outcast. 2) Teacher says to other pupils to be friends with him. 3) He is a nice boy, let’s take him along [pupils]. 4) It’s nice for the boy to get friends [a teacher]. 5) The pupils are happy and work together. (6th grader, picture 4)

6.2 The intertwined relationship between school-related affections and a sense of belonging

The students’ sense of emotional engagement was characterized by the balanced or unbalanced dynamics between the affective and the social dimension in the school’s everyday life. With the balanced dynamics, a high sense of belonging was connected to positive affects towards schoolwork and valuing schoolwork. Conversely, with the unbalanced dynamics, tension between the affective and the social dimension was typical. We identified four types of dynamics for emotional engagement in schoolwork in both the teacher–student and peer interactions: (1) constructive balance, (2) academic friction, (3) social friction, and (4) alienation. The constituents of affective dimensions stressed by students, i.e. valuing schoolwork and enjoying learning were examined in each profile (see Table 1). Respectively, emotional and informational support and social cohesion, which proved to be key elements contributing to the social dimension, were examined in each profile (see Table 1).

The constructive balance between the school-related affects and a sense of belonging (High–High) was the most dominant profile both in peer interaction and (34 %) the teacher–student interaction (46 %; see Table 1). Students described that valuing of schoolwork, enjoyment of learning, constructive social cohesion, receiving emotional and informational support in the teacher–student and/or peer interaction occurred simultaneously and formed a coherent social learning environment. In situations where the peers’ ability to share knowledge and provide advice and guidance contributed to the value of the schoolwork, it also facilitated the students’ persistence when encountering problems with academic tasks. Moreover, the students described collaborative efforts to master challenging academic tasks.

1) A group of three boys has come to show the teacher their work. The teacher and the boys talk about the project. 2) The boys have decided to prove that boys can work hard at school, too. That’s why they do extra work. 3) Gosh, we wish the teacher would let us tell the whole class. It’d help us. We could all improve our grades and become better in speaking in front of the class. Let’s hope so. 4) Oh, I see. Now the boys have taken the bull by the horns and started putting some effort into their schoolwork. Maybe it’ll encourage the other boys to speak publicly, too. Perhaps their grades will start looking a little different, too. I’m really looking forward to their presentation. 5) The boys get a chance to present their work to the class and the teacher is very proud of them. (6th grader, picture 4)

Similarly, informational support received from the teacher was reported to be crucial to the valuing of schoolwork. However, mere informational support did not ensure positive affects towards studying. Enjoyment of learning was described only when emotional support was received from teachers or peers.

1) With the help of other pupils, the teacher encourages one pupil to read/to do maths. 2) The pupil reading/doing maths couldn’t read/do maths. 3) Others encouraged the pupil to read/to do maths. They [pupils] were happy when s/he succeeded. 4) The teacher was happy when the pupil learned. 5) The pupil is happy s/he learned to read/to do maths. (8th grader, picture 4)

1) The class is listening to the pupil standing in front of the class. They are taking notes. 2) The teacher asked the pupil to come to the front of the class. 3) The pupils respect the pupil who is standing in front of the class. 4) How nicely the pupils listen to the one speaking. [teacher] 5) Next the pupil goes back to his/her seat and the others applaud because they respected the presentation. (8th grader, picture 3)

Close relations, i.e. social cohesion between students, enable students to identify shared goals in terms of academic tasks. For instance, the benevolent peer rivalry resulting in an increased effort in studying was typically triggered by a combination of a sense of belonging, positive affects, and a positive attitude towards the schoolwork.

1) These are first-grade pupils. The teacher is listening to a pupil’s reading assignment. 2) The teacher gave the reading assignment to the class the day before yesterday and is now going round from group to group to see how they are doing with it. 3) The pupil in front of the teacher is happy with himself because he has learned to read well. The other pupils in that group are eagerly waiting for their turn to show the teacher how well they have learned to read, too. 4) The teacher is also very happy with the reading of the pupil in front of him/her because this pupil has had difficulty reading before. 5) The teacher commends the pupil on how well he is doing and the pupil feels really good. Next it’s time for the other pupils in the group to show their skills. They are under some pressure and feel a little insecure because the first boy did so well. In the end, all the boys in the group do a good job. (8th grader, picture 4)

The destructive social friction between the positive school-related affects and a lack of sense of belonging (High–Low) was a typical profile in peer interaction (31 %), but a marginal profile in the teacher–student interaction (13 %). A characteristic of these dynamics was that students valued their schoolwork, but they did not enjoy learning. For example, students described their own efforts to carry out the given academic task, but they lacked emotional or informational support and an experience of social cohesion with their peers or teachers. Peer interaction was often characterised by contempt, derogatory behaviour and disrespect, especially in learning situations where a lack of competence or a need for help was evident. However, peer rejection sometimes also resulted from the students’ succeeding in their academic task.

1) The others are laughing at the boy who raised his hand. 2) When the boy raised his hand and gave the wrong answer. 3) “What a stupid boy he is!!” “Why do I always make a mess of it?” [pupils] 4) Wish they’d just shut up… [teacher] 5)—(6th grader, picture 3)

1) All the pupils are doing their own stuff except for Jukka who is actively following the lesson. 2) When the lesson began. 3) God that Jukka is such a swot. [pupils] 4) Why is Jukka the only one who’s active? [teacher] 5) The situation remains unchanged. (6th grader, picture 3)

Due to a lack of a sense of belonging to a peer group, some students reported experiences of loneliness, insecurity, shame and fear. This resulted in negative affects towards studying and, especially, a lack of enjoyment in learning, even though the schoolwork was considered important.

The lack of emotional and informational support from teachers was associated with feelings of frustration, annoyance, irritation and dissatisfaction towards schoolwork in the students’ reports. At the same time, the students still emphasised the value of schoolwork and their own efforts in studying at school. Students described a student being neglected by teachers and the teachers’ reluctance to help in learning tasks. This caused frustration and annoyance towards teachers and inhibited the enjoyment of learning.

1) The pupil asks for advice on an assignment. 2) The pupil didn’t know how to complete the assignment. 3) I have no idea what to do here. [pupil] 4) Do I need to help you again. [teacher] 5) The pupil completes the assignment. (8th grader, picture 4)

The destructive academic friction between low school-related affections and a high sense of belonging (Low–High) was a typical profile in the peer interaction (30 %), but a marginal profile in the teacher–student interaction (13 %; see Table 1). The dynamics were characterised by negative affects and a low valuing of schoolwork combined with a sense of belonging. For example, students expressed feelings of frustration, and they frequently questioned the point of school attendance. However, a sense of belonging—especially in the peer group—was appreciated. Feelings of connectedness within the peer group were upheld by socialising with peers, having fun, and relaxing during the school day. Negative affects towards schoolwork were often shared, hence not valuing schoolwork and a lack of enjoyment of learning constituted the core of social cohesion among peers and upheld the sense of belonging to the peer group. Students also described emotional support received from peers, but it typically reasserted students’ misbehaviour in terms of the academic activities provided by the school, such as resisting the school’s rules and the instructions received from teachers.

1) The pupils are in the classroom, making a big noise. Ilias is about to hold his hand up, and when he gets permission to speak, he starts shooting his mouth. 2) Ilias wanted to be funny. 3) “LOL Ile’s sooo funny xdxd” “Woohoo I’m the king, everyone’s larfing… ‘cept the teacher, well she’s an old fart anyway.“[pupils] 4)—(6th grader, picture 3)

1) Pupils are going crazy, the swot is swotting. No one’s interested in listening. No one’s obeying. 2) The lesson begins. 3) They can go crazy! [pupils] 4) Stop making a racket! [pupils]Wish the lesson would end. [teacher] 5) The bell rings. (8th grader, picture 3)

In this profile, teachers were described as supporting students’ positive affects towards schoolwork, but without success. Teacher behaviour was described as encouraging and aimed at providing emotional and informational support to students. Even though the students reported feeling bored in lessons, finding academic tasks challenging, or failing to focus on their work, teachers were considered supportive. Students acknowledged and valued the teachers’ capacity to appreciate students, and to ‘keep their cool’ in resolving challenging situations with students (e.g. when students have broken the school rules). However, the teachers’ emotional or informational support did not contribute to the students’ positive affects towards schoolwork.

1) The teacher teaches pupils. 2) Pupils don’t know how to do an exercise. 3)“Boring” [pupils] 4) Can I teach in the right way. [teacher] 5) The pupils understand. (6th grader, picture 4)

Alienation, including both the negative school-related affections and a lack of a sense of belonging (Low–Low) was rarely reported in peer interactions (5 %). However, not valuing schoolwork, a lack of enjoyment of learning, a lack of emotional and informational support and social cohesion were more often expressed in the teacher–student interaction (28 %). Off-task behaviour and not paying attention to instructions were typical. Moreover, experiences of frustration and disturbing others in lessons were dominant factors that contributed to negative affects towards schoolwork and triggered alienation from meaningful learning.

1) A pupil starts making jokes at another pupil’s expense. 2) When the pupil was holding his hand up. 3) This won’t lead to anything good. [pupil] 4) What’s going on in that boy’s head. [teacher] 5) The teacher takes the boy to the headmaster to be told off. (6th grader, picture 3)

The dynamics of the teacher–student interaction were characterized by a lack of respect and appreciation. Students described not receiving the support needed or being provoked by teachers, which further weakened the students’ positive affects towards schoolwork. However, according to the students’ reports, the most dominant factor that caused alienation from schoolwork was the teacher’s reluctance to continuously modify social relations in the classroom and to construct a reciprocal learning environment for students.

1) The pupil can’t understand the topic and asks for remedial teaching. The teacher says you have got to get this on your own, it can’t be taught. 2) The pupil didn’t know how to do it and the teacher went to help him/her. 3) I don’t get it, it’s so confusing. I wasn’t here when they taught this and NOW NO ONE’S HELPING ME!!! 4) Why can’t that brat understand this! [teacher] 5) The teacher goes to the blackboard to write down calculations. (8th grader, picture 4)

1) The pupils are in class, writing like they do every time! 2) When the pupils go in the classroom. 3) The pupils write: NOT THE SAME WRITING AGAIN. A pupil holds his/her hand up: My hand’s going numb can’t you see me. 4) C’mon boring just write already. Oh bother [teacher] 5) When the pupils get out of class, their wrists hurt from all the writing. (8th grader, picture 3)

1) The teacher asks the pupils questions about the subject. 2) The lesson & studying begin. 3) “Booooorinngg… When’s the break…?“4) “Another lesson, another group of kids. It’s the crazy class again… sigh.” (8th grader, picture 3)

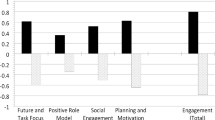

6.3 Students’ emotional engagement at different school levels

There were some differences between primary (sixth-grade) and secondary (eighth-grade) school students’ reports of emotionally engaging school experiences. Table 2 shows that primary school students more often expressed balanced and emotionally engaging dynamics (High–High), i.e. positive affects towards studying, valuing schoolwork and a sense of belonging in the teacher–student interaction than secondary school students. In peer interaction, no difference was detected between the school levels in terms of balanced emotional engagement (High–High) or complete alienation from schoolwork (Low–Low) (see Table 2).

However, primary school students (sixth-graders) more often described social frictions (High–Low) than eighth graders, including a low sense of belonging in peer interaction, combined with positive affects towards schoolwork. In turn, academic friction (Low–High), entailing a high sense of belonging in peer interaction combined with the negative affects towards schoolwork, was more regularly reported among secondary school students (eighth-graders; see Table 2).

Further investigations showed that in the teacher–student interaction, balanced emotional engagement (High–High) or complete alienation from schoolwork (Low–Low) were dominant dynamics at both school levels. However, emotional engagement characterised by social (High–Low) and academic (Low–High) frictions were more typical in peer interaction (see Table 2).

7 Discussion

7.1 Findings in the light of previous literature and pedagogical implications

The results of the study are in line with the idea of emotional engagement as a multifaceted structure that includes both affective and social dimensions. The main elements of the affective dimension are valuing schoolwork and the enjoyment of learning, and the main element of the social dimension is a sense of belonging in terms of social cohesion and support experienced by students. Furthermore, the results suggest that emotional engagement has internal dynamics in which the affective and social dimension influence each other, regulating the students’ sense of emotional engagement. Consequently, neither of the dimensions alone results in strong, balanced emotional engagement.

The quality of interaction with teachers and other students plays an important yet different role in the construction of the dimensions of emotional engagement. According to our results, as a part of emotional engagement, a sense of belonging at school requires experiences of social cohesion, and this is constructed by emotional and informational support from both teachers and peers. Earlier studies have found connections between supportive relationships and motivational outcomes (Wentzel 1998) and reported that teacher and peer support is positively associated with students’ enjoyment and interest at school and their further achievement (Ahmed et al. 2010; Wentzel 1998). However, in our data, students perceive providing and receiving social support as the key element in their sense of belonging, which in turn makes it a necessity in the construction of the students’ emotional engagement with schoolwork. Moreover, the significance of informational support received from peers in the construction of emotional engagement in schoolwork is important in terms of developing a pedagogy that is more engaging and utilises peer interaction as a resource for learning, not just for climate or school satisfaction.

We have identified four qualitatively different profiles, including balanced and unbalanced emotional engagement. These profiles vary in terms of interactional context. More precisely, the relation between the affective and social dimension was more unbalanced in peer interaction than in the teacher–student interaction at both grade levels. This seems to suggest that the tensions in peer interaction at school make for a more complicated context in terms of emotional engagement. In line with previous studies, the profile of academic friction implies that experiencing a sense of belonging in peer interaction does not ensure positive school-related affections, and can in fact have the opposite effect (Sage and Kindermann 1999). Adolescents’ need for positive and supportive relationships is increased. Hence to strengthen their status and satisfy their need for a sense of belonging to a peer group, students are ready to adopt the norms and values of their peers, even if this requires giving up on academic aspirations (Ulmanen et al. 2014).

The dominance of the profile of academic friction—especially in the older age group—resonates with earlier studies that have shown that an increased risk of alienation from schoolwork along the study path is strongly regulated by the peer group (Berndt 1995). However, the social friction profile in the peer interaction context suggests that a lack of a sense of belonging alone does not explain negative school-related affections. Students might hold on to their academic goals even when they distance them from their peers, and a lack of a sense of belonging in terms of classmates alone cannot hinder students’ experiences of the meaningfulness of the schoolwork (Finn 1989). For example, supportive and positive relationships with teachers (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Lee 2012) and family (Furrer and Skinner 2003) may compensate for a low sense of belonging with peers at school. Despite this, according to our results, a lack of a sense of belonging is related to the loss of the joy of learning. Enjoyment of learning occurred only in the balanced profile, where a strong sense of belonging was also reported. As such, these results indicate that a strong sense of belonging is a requirement for the actualisation of students’ holistic emotional engagement in the school community. Moreover, the function of peer interaction for emotionally engaging school experiences is complex, but nevertheless vital for adolescent students.

In the teacher–student interactions, the students’ reports are polarized into the profiles ‘alienation’ and ‘balance’, indicating that a sense of belonging in the teacher–student interaction resonates strongly with students’ school-related affects and valuing of schoolwork (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Klem and Connell 2004; Lee 2012). This is even more evident with the eighth-graders. Differences between the contexts of the teacher–student interaction and peer interaction can be explained by the teachers’ institutional role; teachers represent the academic goals set by the school, and if the student cannot perceive those goals to be significant or even relevant, frustration may be directed at the teacher. However, students also describe a weak sense of belonging caused by a lack of emotional and informational support from teachers. This may be due to the structure of the school day in the subject-teacher system of secondary schools, which may hinder students’ opportunities to create close relations with teachers. The study confirms earlier findings suggesting that the role of received social support from the teacher is crucial for emotional engagement, and this effect increases through the teenage years (Eccles and Roeser 2011; Feldlaufer et al. 1988; Midgley et al. 1989).

The results imply that understanding the dynamics between social and affective dimensions is central to facilitating emotional engagement. Moreover, it is important to understand that the dynamics vary depending on the social contexts in the school. In order to facilitate students’ emotional engagement, students’ different ways to engage emotionally in the school’s pedagogical processes must be identified. More precisely, students’ opportunities for interaction that promote experiences of the meaningfulness of schoolwork with teachers and especially with peers should be kept in mind when designing pedagogical practices. Particular focus is needed to develop the school environment so that students would not have to choose between schoolwork and peers. It would require that interaction among peers is modified and directed to school-related goals much more consciously. Students should be encouraged to give and receive peer support in terms of schoolwork.

The results of the study are in line with the acknowledgment of adolescent students’ strong need to be heard and noticed; experiencing social cohesion is important in sustaining students’ academic and affective development and wellbeing. There is a strong consensus among researchers that a caring and supportive school environment is vital to school success, especially with adolescents. Moreover, there is also strong evidence that the school may counteract negative contextual factors, such as unstable family conditions, and motivate students to try harder, thus offering them the building blocks for positive future orientations. The findings in this study may inform schools about how to build a more emotionally engaging social environment and help adolescents to find and sustain a constructive balance between their need to belong and their attitudes and feelings towards schoolwork.

7.2 Methodological reflections

Using the picture tasks, we collected extensive data consisting of students’ reports of the school environment. The reflective research design gave the students an opportunity to project their perceptions of schoolwork and the social environment of the school. Hence, the findings may be transferable to further studies on students’ emotional academic engagement. However, due to the distinctive features of the Finnish comprehensive school system (Sahlberg 2011) and the limited sample size (n = 167 students), generalising the results to other systems and other countries should be done with caution.

Qualitative analysis allows for the exploration of the complexity of the emotional engagement experienced by students in everyday school life. Moreover, the reflective technique used is predicated on the assumption that students will cast their unfiltered perceptions, feelings, and desires onto neutral images (Branthwaite 2002), and it is a suitable strategy to facilitate the expression of internal content, which is often subconscious and escapes rational thought, thus making it difficult to articulate. The method, however, does not necessarily produce descriptions of factual events, but rather projections of the students’ perceptions and feelings. Therefore, the interpretations of the results can also be used as guidelines for future research questions, such as how intentionally students choose the object of their engagement—for example, when they have to choose between their peers and their schoolwork—and what kind of learning environment would make this kind of decision unnecessary.

References

Ahmed, W., Minnaert, A., van der Werf, G., & Kuyper, H. (2010). Perceived social support and early adolescents’ achievement: The mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 36–46.

Anderman, L. H. (2003). Academic and social perceptions as predictors of change in middle school students’ sense of school belonging. Journal of Experimental Education, 72(1), 5–22.

Anderman, L. H., & Anderman, E. M. (1999). Social predictors of changes in students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24(1), 21–37. doi:10.1006/ceps.1998.0978.

Anderson, A. R., Christenson, S. L., Sinclair, M. F., & Lehr, C. A. (2004). Check and connect: The importance of relationships for promoting engagement with school. Journal of School Psychology, 42(2), 95–113. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2004.01.002.

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2009). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 651–670. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.007.

Audas, R., & Willms, J. D. (2001). Engagement and dropping out of school: A life-course perspective. Quebec: HRDC Publications Centre.

Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1997). Caring school communities. Educational Psychologist, 32(3), 137–151. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3203_1.

Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., & Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: Anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 817–827. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.817.

Berndt, T. J. (1995). Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development, 66(5), 1312–1329. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep9510075265.

Berndt, T. J., Hawkins, J. A., & Jiao, Z. (1999). Influences of friends and friendships on adjustment to junior high school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(1), 13–41.

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., & Patton, G. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 357-e9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013.

Branthwaite, A. (2002). Investigating the power of imagery in marketing communication: Evidence-based techniques. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 5(3), 164–171. doi:10.1108/13522750210432977.

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Crespo, C., Jose, P. E., Kielpikowski, M., & Pryor, J. (2013). “On solid ground”: Family and school connectedness promotes adolescents’ future orientation. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 993–1002.

Debnam, K. J., Johnson, S. L., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2014). Equity, connection, and engagement in the school context to promote positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(3), 447–459. doi:10.1111/jora.12083.

Do, S. L., & Schallert, D. L. (2004). Emotions and classroom talk: Toward a model of the role of affect in students’ experiences of classroom discussions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 619–634.

Dupont, S., Galand, B., Nils, F., & Hospel, V. (2014). Social context, self-perceptions and student engagement: A SEM investigation of the self-system model of motivational development (SSMMD). Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(1), 5–32.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x.

Elffers, L., Oort, F. J., & Karsten, S. (2012). Making the connection: The role of social and academic school experiences in students’ emotional engagement with school in post-secondary vocational education. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 242–250. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.08.005.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38(4), 1025–1034.

Feldlaufer, H., Midgley, C., & Eccles, J. S. (1988). Student, teacher, and observer perceptions of the classroom environment before and after the transition to junior high school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 8(2), 133–156. doi:10.1177/0272431688082003.

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142.

Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. (No NCES-93-470). Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics.

Finn, J. D., & Voelkl, K. E. (1993). School characteristics related to student engagement. The Journal of Negro Education, 62(3), 249–268.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148.

Gonida, E. N., Voulala, K., & Kiosseoglou, G. (2009). Students’ achievement goal orientations and their behavioral and emotional engagement: Co-examining the role of perceived school goal structures and parent goals during adolescence. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 53–60. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.04.002.

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. doi:10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831.

Hallinan, M. T., & Williams, R. A. (1990). Students’ characteristics and the peer-influence process. Sociology of Education, 63(2), 122–132.

Harel-Fisch, Y., Walsh, S. D., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Amitai, G., Pickett, W., Molcho, M., & Craig, W. (2011). Negative school perceptions and involvement in school bullying: A universal relationship across 40 countries. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 639–652.

Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Kandice, S. (2002). Investigating “sense of belonging” in first-year college students. Journal of College Student Retention, 4, 227–256.

Ikeda, M. (2013). Pisa in focus. What do students think about school? (No. 1). Paris: OECD.

Israelashvili, M. (1997). School adjustment, school membership and adolescents’ future expectations. Journal of Adolescence, 20(5), 525–535. doi:10.1006/jado.1997.0107.

Janosz, M., Blanc, M. L., Boulerice, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2000). Predicting different types of school dropouts: A typological approach with two longitudinal samples. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 171–190.

Ketonen, E., & Lonka, K. (2013). How are situational academic emotions related to teacher students’ general learning profiles? In K. Tirri & E. Kuusisto (Eds.), Interaction in educational domains (pp. 103–114). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Nurmi, J., Leskinen, E., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2008). Peer group influence and selection in adolescents’ school burnout. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(1), 23–55.

Klasen, S. (1999). Social exclusion, children and education: Conceptual and measurement issues. In: Background Paper for OECD. Munich: University of Munich.

Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 262–273. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x.

Lee, J. (2012). The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 330–340. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.006.

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233–247. doi:10.1037/a0021307.

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2013). Interrelations of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive school engagement in high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(1), 20–32.

Li, Y., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). Personal and ecological assets and academic competence in early adolescence: The mediating role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 801–815.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 274–283. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08284.x.

Ma, X. (2003). Sense of belonging to school: Can schools make a difference? The Journal of Educational Research, 96(6), 340–349. doi:10.1080/00220670309596617.

Mäkinen, J., Olkinuora, E., & Lonka, K. (2004). Students at risk: Students’ general study orientations and abandoning/prolonging the course of studies. Higher Education, 48(2), 173–188.

Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327–365. doi:10.3102/0034654308325583.

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 1, No. 2).

Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development, 60(4), 981–992. doi:10.2307/1131038.

Nicholls, J. (1990). What is ability and why are we mindful of it? A developmental perspective. In R. Sternberg & J. Kolligian (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 11–40). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M., & Kaplan, A. (2007). Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 83–98. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83.

Phillips-Howard, P. A., Bellis, M. A., Briant, L. B., Jones, H., Downing, J., Kelly, I. E., et al. (2010). Wellbeing, alcohol use and sexual activity in young teenagers: Findings from a cross-sectional survey in school children in north west england. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy,. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-5-27.

Porr, C., Mayan, M., Graffigna, G., Wall, S., & Vieira, E. R. (2011). The evocative power of projective techniques for the elicitation of meaning. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(1), 30–41.

Ramelow, D., Klinger, D., Currie, D., Freeman, J., Damian, L., Negru, O., et al. (2012). Social context school. In C. Currie, C. Zanotti, A. Morgan, D. Currie, M. de Looze, C. Roberts, O. S. Samdal, & V. Barnekow (Eds.), Social determinants of health and well-being among young people health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey (6th ed., pp. 45–63). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents).

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ psychological and behavioral functioning in school: The mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408–422. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.88.3.408.

Sage, N. A., & Kindermann, T. A. (1999). Peer networks, behavior contingencies, and children’s engagement in the classroom. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(1), 143–171.

Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in finland?. New York: Teachers College Press.

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Pietikäinen, M., & Jokela, J. (2008). Does school matter? The role of school context in adolescents’ school-related burnout. European Psychologist, 13(1), 12–23. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.13.1.12.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525.

Trigwell, K., Ellis, R. A., & Han, F. (2012). Relations between students’ approaches to learning, experienced emotions and outcomes of learning. Studies in Higher Education, 37(7), 811–824. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.549220.

Ulmanen, S., Soini, T., Pyhältö, K., & Pietarinen, J. (2014). Strategies for academic engagement perceived by finnish sixth and eighth graders. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(3), 425–443. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2014.921281.

Voelkl, K. E. (1997). Identification with school. American Journal of Education, 105(3), 294–318.

Wang, M., Willett, J. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2011). The assessment of school engagement: Examining dimensionality and measurement invariance by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of School Psychology, 49(4), 465–480. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2011.04.001.

Wellborn, J. G., & Connell, J. P. (Eds.). (1987). Student engagement and disaffection in school student report. Rochester, NY: Rochester Assessment Package for Schools.

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 202–209. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202.

Willms, J. D. (2003). Student engagement at school. A sense of belonging and participation results from PISA 2000. Paris: OECD.

You, S. (2011). Peer influence and adolescents’ school engagement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 829–835. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.311.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M., Chipuer, H. M., Hanisch, M., Creed, P. A., & McGregor, L. (2006). Relationships at school and stage-environment fit as resources for adolescent engagement and achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 29(6), 911–933. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.008.

Acknowledgments

The funding of the study: The Finnish Cultural Foundation and Ministry of Education and Culture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ulmanen, S., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J. et al. The anatomy of adolescents’ emotional engagement in schoolwork. Soc Psychol Educ 19, 587–606 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9343-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9343-0