Abstract

This paper explores the role of deliberation in the context of the capability approach to human well-being from the standpoint of the individual doing the reflecting. The concept of a ‘strong evaluator’ is used develop a concept of the agent of capability. The role of values is discussed in the process of deliberating, particularly the nature of and difference between prudential values and intrinsic values. Some consideration is given to the limits and constraints on deliberation and finally a brief example of deliberation is considered—that of occupational choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this paper I wish to explore deliberation in the context of the capability approach to human well-being. The perspective will therefore be that of the individual reflecting on her capabilities and deliberating on the range of opportunities for engaging, doing and being. Thus I will not be adopting the perspective of the policy maker or decision maker who is trying to figure out how to make such opportunities available. Adopting the perspective of the subject or self of capability will, I hope, illuminate certain aspects of the capability approach. But above all, my aim is to show the importance of deliberation and its role in the pursuit of what Amartya Sen terms “well-being freedom”, that is, the freedom an agent has in pursuing his or her well-being.

The paper is in six sections. First, I explore the kind of self that is the subject of capability. This could be seen as analogous to Michael Sandel’s work on exploring the self or subject of justice in his analysis of Rawls’ theory of justice—though I’m not claiming the same kind of significance or importance for my own few remarks as that which characterises Sandel’s ideas. The main point I wish to make here is that if we are to take seriously the idea of deliberation in the context of the capability approach then this commits us to certain beliefs about the nature of the self who is doing the deliberation. I then turn to a consideration of functionings and just what kind of things they are, and the relation between functionings and well-being. This is important if we are to have a clearer idea of just what a purported self is deliberating about. But some of what I say will also have implications for what should be included in the scope of well-being and here I’m inclined to think that Sen sometimes construes well-being on a too narrow, self-regarding basis. In the third section, I consider deliberation in the context of prudential and intrinsic values, adapting some suggestions of Sen. In the fourth section I consider factors that affect deliberation over well-being, where well-being is comprised of functionings, with some examples. In the fifth section I make a few brief, but necessary, remarks on the need for reasonableness in deliberating. Finally in the sixth, concluding section, I suggest an approach to one event that occurs pretty well in everyone’s lives at least once and usually more than once—namely career and occupational choice. This event is, of course, inescapable for those completing their educational studies.

I propose a simple working definition of reflective deliberation as a critical assessment of ends and means in respect of well-being. This is sufficient to start off the discussion: what is meant by ends, means and well-being will be clarified as we go on.

The Subject of Capability

Sen has counselled against interpreting well-being in terms of a mental state—happiness. He argues that there are mental states other than happiness that may be relevant to well-being (e.g. I might choose to subject myself to a strict disciplinary regime in the belief that this may enhance my well-being). Furthermore, happiness could be induced (he gives the example of seeking solace through opium in order to forget poverty) which suggests actual doings (and not only the mental experience of such doings) need to be counted in as factors of well-being (see Sen 1985b, pp. 188–189). Finally, persons are often quite able to adapt their mental state to the conditions they are in (with or without the help of opium) and convince themselves that they are happy despite the meagre opportunities available to them. The upshot is that although happiness is a factor of well being it cannot play a key role, let alone the only role, in accounting for well-being. Is it legitimate to assume that what holds for the economist or philosopher in the role of evaluating the constituents of well-being also holds for a person trying to figure out how to get the best out of her life at a particular time? It would be odd to suppose that public policy decisions are made from one set of criteria (namely a scepticism of the role of happiness in well-being) whilst individuals use a radically different set of criteria, namely a set that includes mental state happiness as the key component of well-being. One would expect some congruence as far as the two perspectives are concerned, namely that the kinds of reasons adopted by policy makers in providing opportunities for well being are also the kinds of reasons individual citizens will adopt in deciding which opportunities to take up. I do not insist upon such congruence, namely that it is reasonable to expect it.

Sen also considers another approach to well-being, namely the satisfaction of desire (which leaves out of account whether or not the person is happy as a result of her desires being satisfied). But this seems inadequate if it implies that the value of a state or activity as a part of well-being is dependent on my desiring it. Rather, it would appear that the value of something is not simply reducible to a desire for it: “my desire that a certain state of affairs should obtain reflects my judgement that that state of affairs is desirable for some reason other than the mere fact that I prefer it” (Scanlon, p. 192). Sen puts the point equally effectively:

Compare the two following statements:

(I) I desire x because x is valuable for me

(II) X is valuable for me because I desire x

The former statement is intelligible and cogent in a way the latter clearly is not. Valuing something is a good reason for desiring it but desiring something is not an obvious reason for valuing it. (Sen 1985b, p. 190)

What is being proposed, then, is that valuing has a priority over desiring in that an agent is someone who “examines one’s values and objectives and chooses in the light of those values” (Sen 2002, p. 36). But it is Charles Taylor who has, perhaps, done most to develop this concept of the self in terms of, as he puts it, a “strong evaluator” (see Taylor 1985 passim, but especially Ch 1 for an introduction the concept of strong evaluation). Taylor explains that ‘weak evaluation’ is only concerned with the evaluation of the best means to attain pre-given ends (e.g. ends delivered through desires) whereas strong evaluation seeks to shape and modify existing ends.

I suggest, then, that the subject of capability be viewed as a strong evaluator in Taylor’s sense. The capability approach, it will be recalled, invites us to consider the beings and doings that constitute well being as so many functionings or, as Sen puts it, as a set of functioning vectors (Sen 1985b, p. 201). In this evaluative space, the self is a strong evaluator in that the value of a particular functioning is in itself a strong reason for doing it. This does not imply that our agent is only motivated to undertake activities that only have a conventionally high value (opera, Shakespeare, etc.). Rather, it implies that the agent is someone who thinks about her life in terms of ends. These valued states of being are possibilities that may be realised through a set of functionings. They may not involve any opera or Shakespeare whatsoever. For example, a valued end may consist in caring and being cared for in which case a set of functionings could involve parenting and local self-help projects. They may indeed afford considerable happiness and even pleasure; but for all that the person is acting as a strong evaluator.

There is another feature of the self of the capability approach, which concerns freedom. Sen has explained how we need to distinguish between freedom as direct control and freedom as preference (see Sen 1985c, pp. 208–210 and also Pettit 2001). The opportunities for functioning available to me may well fulfil possible preferences I may have (had it been in my power I would have brought about these opportunities myself) but my freedom is not diminished one jot if such opportunities have been provided for by someone else (e.g. by my local council or even supermarket). Direct control of functionings is not required by the capability approach and neither is it even desirable. For example, some parents may choose to educate their children themselves: but this is not ipso facto better than state provision of education simply because they, the parents, are doing the teaching rather than paid teachers.

Now, freedom is not simply enhanced through extending the range of preferences—indeed an excess of choice can be time-consuming and in fact lead to a decrease in well-being (Sen 1992, p. 63). In any case, extending the provision of functioning vectors may have only a marginal effect on my freedom even if I do have the time to devote myself to choosing from different kinds of services and products. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the subjects of capability do have particular reason to value direct freedom. Strong evaluators want to see themselves enacting and living out their valued activities through their own agency where this is practically feasible. It is not feasible at all when one has to report to the local hospital for medical treatment. But it is much more feasible in other spheres—say education and learning. And for some functionings it seems indispensable—participating in the community, for example. Strong evaluators, I suggest, have a predilection for direct freedom (whether individually or jointly) and this figures in their well being. They value those opportunities for functioning that enable them to exercise free deliberation and choice. How much of that functioning will be of this kind will vary although one major factor is simply that of making time. Nevertheless, direct freedom—what Sen also calls agency freedom, the ability to promote goals one has reason to value (Sen 1992, p. 60) is significant for the subjects of capability.

Functionings and Freedom Well-Being

The quality of life can be gauged by a capability set, that is, the set of functionings in which a person is engaged. Examples of functionings include having mobility, nourishment, escaping morbidity, being happy and achieving self-respect. Clearly, this range of ‘doings and beings’ could be extended almost indefinitely. It may be helpful, therefore, to employ a distinction taken from philosophical logic and distinguish ‘type’ functionings from ‘token’ functionings. Tokens then become specific instances of types so that, for example, the type functioning ‘participating in the community’ may be instantiated by the tokens of running for office, clearing up the local environment or setting up a nursery. The primary objects of capabilities are type functionings, on this analysis: we can see if there is a capability in respect of a type functioning by examining the opportunities for token functioning. This level of generality is important if capabilities are not to collapse into competencies and if, in the field of education at any rate, learners are not obliged to develop a capability for each token functioning. If the type-token distinction is perceived as a little clumsy then perhaps some readers may prefer to refer to generic and specific functionings: but in most cases the context will make it clear the kind of functioning that is being referred to.

Capability development relates both to the creation of opportunities and to the ability to make the best of those opportunities. The former aspect is dependent on social and political processes usually not under the direct control of individuals but the other aspect—what might be called the agency aspect of capability—is very much of direct concern to the individual. In terms of this agency, a person may deliberate about the kinds of functionings she already is capable of engaging with and the kinds of functionings she would like to engage in and whether, concerning these, there are capabilities that need to be developed first. As a strong evaluator, the focus will initially be on generic (type) functionings (e.g. participating in the community) and then looking at the possibilities of specific (token) functionings. If there is a paucity of the latter than the inference must be that whilst there is a wish for certain kinds of functionings, the effective capability is lacking. Must a person always deliberate from type to token in this way? Of course not: a person may stick to deliberating about token functionings, a range of specific beings and doings. But in cases of conflicts of functionings or of the above-remarked paucity there will be an incentive to step back a little and deliberate at the level of type functioning.

In deliberating am I committing myself to an active life, to a vita activa? It was Gerry Cohen who raised the spectre of the capabilities approach as advocating a sporting, performative view of the quality of life, in which a person “fulfils their potential through activity” (Cohen 1993, p. 24). But if we think of capabilities in terms of functioning opportunities then it is clear that the content of the functioning doesn’t need to be one of intense activity. Spending an afternoon gardening is one kind of functioning but spending an afternoon sitting in the garden is another kind of functioning and the capabilities approach privileges neither. Moreover, as Philip Pettit has pointed out, the capability to function doesn’t necessarily imply direct freedom and control over functioning: what counts is whether the preference regarding different types of functioning is decisive (i.e. if I choose functioning A in preference to functioning B there really is a choice in as much as had I chosen the other way round then that choice would have been equally decisive (Pettit, p. 3). And although I’ve said that strong evaluators have a preference for engagement so that they enact what they value, that doesn’t privilege a busy life over a life of leisure in which I thoroughly enjoy my (somewhat overgrown) garden.

One might complain, of course, about the need to be a strong evaluator in the first place, but to this I’m inclined to think that it goes with the territory of freedom. If I don’t even deliberate then it’s not clear that I’m exercising any kind of self-formation or agency. Thus I may, as a strong evaluator, decide to live from one moment to the next, to take life as it comes. I suspect that it would be fairly difficult to actually lead a life like this: one would need to renew regularly one’s resolve to live in such a way and make sure that one wasn’t caught out secretly deliberating. Nevertheless, being a strong evaluator doesn’t necessarily entail a life of constant deliberation and lack of spontaneity. Could one reject the very idea of being a strong evaluator in the first place? It will be recalled that in Sartre’s account of freedom, bad faith was the condition in which an agent pretended to herself that she wasn’t free: for Sartre one could never not be free. Similarly, one can never not be a strong evaluator: it comes with the territory of agency and rationality.

Does my well-being consist of chiefly self-regarding activities? Sen sometimes seems to suggest this, since on several occasions he has distinguished sharply between agency achievement and well-being achievement. The former includes goals that may impinge on my well-being but are nevertheless separate from it, even though they might be things I care a great deal about (e.g. the independence of my country or the elimination of famines (Sen 1992, pp. 57–58). But whilst the distinction in itself is valid enough Sen is, in my view, inclined to assign to agency achievement goals that are better considered a part of well being. Take, for example, a person enjoying a quiet sandwich on the riverbank, whose peace is shattered by the irksome decision of whether to rescue someone who is drowning in the river right next to him. For Sen, well-being is firmly equated with staying put and finishing off one’s sandwich (Sen 1985c, pp. 206–207) whilst rescuing the person is assigned to a valued agency goal. But I am inclined to assign the act of rescue into the vector of functionings that constitute well-being, and accept that such a vector will include different weightings and even conflicts: well-being is not always seamless enjoyment.

Or again, take the example of a doctor who is considering taking up a position in a poor country where she could nevertheless make a real impact. Sen suggests that she might be forced to sacrifice her well-being in favour of goals consistent with agency freedom (Sen 1992, p. 61). But as the discussion makes clear, the well-being that might be sacrificed is that of comfort and enjoyment. Whereas what we might have expected is that included in well-being could be the doing of good deeds in a far away poor country. Well-being needn’t exclude other-regarding activities and it needn’t exclude the domain of the ethical.

In fact, Sen also suggests that well-being may include other-regarding concerns providing these operate through some feature of the person’s own well being. But he then goes on to say that “doing good may make one contented or fulfilled” leaving it unclear as to whether such an action can only be a part of well-being because it brings about pleasure or as a constituent of well-being. If we take the latter approach (and this seems to flow with the general tone of what Sen says in this passage) then the concept of strong evaluation can be of some assistance: for the strong evaluator may well include in her concept of well-being ends in life that include caring for others, even if these are construed as duties. The occurrence of events may call for a considered revision of what counts as one’s well-being, but this is to be expected.

Reflecting on Functionings: Prudential and Intrinsic Values

I have already suggested that not all ethical choices need be at variance with well-being. In this section I wish to examine, briefly, prudential values and intrinsic values. By ‘prudential’ I refer to those values that can be characterised in terms of our purposes, interests and aspirations, such as professional success and recognition, prosperity and comfort—what one might term worldly values. Now, for a strong evaluator, not all values will be prudential in this sense. She has a concept of the ends of a life and her concept of functionings will reflect this. This may, of course, involve a plurality of values—examples could include caring and parenting, creativity, caring for the natural world, sport and games, citizenship or the opposite, the longing for a private life and to be left alone. Activities that reflect these values are undertaken for their own sake. There is a certain flux as far as the contrast between prudential and intrinsic values are concerned. One person’s prudential value (making money) may be another’s intrinsic value (doing business). It is unlikely that a person’s life will be enacted entirely in line with just the one type of value and one would normally expect to see a mix of prudential and intrinsic values, the balance of which may shift back and forth over a lifetime.

The logic of the idea of the strong evaluator suggests that not all activities will be instrumental (see Aristotle, 1980, Nicomachean Ethics, Ch 1, Book 1 for the classic statement of this relationship). Activities may be valued both for themselves and also instrumentally—for example, creativity or professional competence may bring material rewards. But at least some of a person’s ‘beings and doings’ will be done for their own sake and persisted with whether or not they yield some kind of material reward or benefit. James Griffin suggests that values are linked to accomplishments which are seen as giving a life weight or point (Griffin 1991, pp. 59–60). Here we need to distinguish between agent-relative achievements and achievements of value. It is the former that are the principal constituents of well-being. I might persist in an activity—e.g. playing a musical instrument—and think it worthwhile whilst acknowledging I do not accomplish anything very much of value, at least compared to the achievements of great musicians.

What procedures might the subject (agent) of capabilities use in deliberating on functioning vectors? Sen has given us a brief analysis of evaluation methods of capabilities from the perspective of policy makers and evaluators (Sen 1999, pp. 81–83) and elements of this are of help to us as well. We, however, are focussing on functionings from the standpoint of the agent of capability: given certain capabilities, what functionings are available, given that a capability can potentially deliver a range of functionings from which the agent is likely to select only a subset?

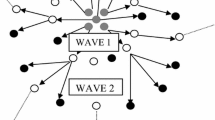

Let us address first of all, adapting what Sen calls the direct approach, the possible functionings themselves. It is unlikely that the agent will adopt a total comparison, i.e. attempt to evaluate all the possible functionings open to her based on her complete capability set. We have already seen that total life plans are neither plausible or necessarily desirable. More likely is a partial ordering in which some sets of possible functionings are compared, yielding a provisional and partial ranking. But the agent is not simply comparing possible functionings in the manner of random beings and doings. They will be specific (token) functionings associated with a capability (e.g. the capability of participating in community life). Indeed, the advantage of the capability perspective, from the standpoint of the deliberating agent, now starts to become clear. For the capability approach gives the deliberating process a clear structure such that the agent is not simply deliberating about random functionings, random ‘beings and doings’: she is deliberating about functionings through the grid of capability.

The process is given more complexity through the fact that opportunities for functionings are also considered. The reflective process also needs an informational base which may yield a null set of functionings once opportunity is taken into account. Reflection therefore considers both opportunities for functioning as well as the merits of the functioning itself: the ease or otherwise of securing an opportunity is weighted against the merits (value) of the functioning. The question then arises as to whether these opportunities are simply non-existent or whether they could be turned into functionings if hitherto under-developed capabilities could be brought into play. This consideration would then lead the agent to address a new set of functionings with this question in mind: if, as a result of engaging in functionings x, y and z, could a platform be provided whereby a new capability was developed which then enabled the pursuit of functionings a, b and c? Clearly, it is this kind of consideration that is involved in learning and education: the development of capabilities at one level enables the further development either of fresh capabilities or a deepening of existing ones. The capability grid thus facilitates reflective learning by giving it a structure through the medium of capability, type and token function, bearing in mind that ‘capability’ is not uni-dimensional but is, as far as the field of learning is concerned, multi-layered.

Sen, in his analysis of methods of evaluating, also mentions what he calls the ‘supplementary’ method in which interpersonal comparisons relating to income are supplemented by an examination of capability. Adapting this, might we not say that the supplementary approach to reflective deliberation happens when the agent wishes to supplement prudential values by intrinsic values? The thought here is that, for whatever reason, the agent decides that the pursuit of purely prudential values is not enough in her life. Reflecting on intrinsic values directs deliberation to possible functionings which then directs attention to capabilities and their development. Indeed, this approach, we may feel, is a familiar one: tiring of the incessant quest to realise prudential value, the agent turns to agreeable (or challenging) supplements, without ever letting go of those prudential values that may be regarded as core. In this case, deliberation starts to become more straightforward than the previous case because the functioning space for intrinsic value is governed by the amount of time and effort needed for prudential value. The agent is still acting in the manner of a strong evaluator, it should be noticed, because she is reflecting on the ends of her life and working out the extent to which prudential values must play a part.

Reflecting on Well-Being: Freedom and Value

We have seen that the subject of capability is a strong evaluator who is concerned about their freedom: freedom is an issue for it. But so is the intrinsic value of functionings, and these two elements, freedom and value play a role in the deliberation of well being. However, the role they each play may be differently weighted which yields a considerable diversity of types of well being (or flourishing), as the following examples illustrate.

The Stressed Professor

Where activities of high value have been freely chosen but with little attendant personal happiness owing to lack of resources, bureaucratic demands, etc. She is flourishing but in a somewhat frustrating way.

The Contented Pensioner

Possibly our professor, now retired. She freely concedes that her gardening, local book club and a little recreational education amount to little of intrinsic value; but these are all freely chosen (they would be irksome if they were not) and give her great pleasure. The value of these pursuits is therefore agent-relative rather than intrinsic.

The Joyous Student

He, being a student of the stressed professor, enjoys engaging in activities of high value which are freely chosen, giving immense satisfaction. Let us suppose, further, that we have a mature student who has undertaken a range of low-value employment before entering university. In his satisfaction, he speaks from experience.

The Defiant Libertarian

This person rates his freedom as his chief good, more important than personal happiness. He resolutely refuses to exercise his capabilities across valuable functionings, in the name of the freedom to do nothing with one’s life. As a consequence of maintaining this stance he has little disposable income and few pleasures in life.

The Ascetic Philosopher

She is chiefly motivated by the study of philosophy to the extent that her own personal happiness is set near to zero. She assesses the worth of a life (her life at any rate) by the value of what it achieves. This even impinges on her freedom for although the life of asceticism was freely chosen in the first place it now consists of daily imperatives that make even the most simplest of freedoms mere indulgences. She lives a life of well-being despite the fact that her own happiness is a low priority.

It seems to me that all these people could be said to enjoy well-being freedom. They are all strong evaluators, but once personal happiness, freedom and the value of functionings are given different weightings the outcomes are radically divergent. Yet they could take place over a single life, at different stages of deliberation—the joyous student, the stressed-out professor and the contented pensioner could all be the same person. These dimensions of well-being can be explored in a single life, permitting a certain play with types of well-being. The plurality inherent in the capability approach enables a degree of experimentation and exploration of a life, in which modes of well-being are also modes of self-identity.

Reasonableness in Deliberating

The consideration by policymakers concerning the kind of opportunities for functioning to be made available may be guided by the constraints of public reason. John Rawls has suggested that such considerations will involve a recognition of certain rights and liberties, an assignment of priorities along with “measures ensuring for all citizens adequate all-purpose means to make effective use of their freedoms” (Rawls 1999, p. 141). Since we are examining deliberation from the standpoint of the agent herself we may take it as a working assumption that in deliberating there will be constraints such that grossly unreasonable functionings will not be readily available as opportunities. Moreover, there should be no expectation that agents, in their personal deliberations, must adopt the guiding ideas of public reason: such an expectation would undermine the whole point of public reason in the first place, certainly as Rawls conceived it. Their deliberations may be guided by a set of considerations wholly removed from those that guide public reason.

Yet it is better that persons do not hanker after opportunities that have little or no merit in the public space of reasons. One solution would be simply to say that deliberations operate within the constraints of public reason and that it would be better if these constraints were internalised by agents: yet as we have seen, it is no part of the idea of public reason that this should be a requirement. There is, however, another approach, which follows through some of the implications of strong evaluation. Briefly, the claim is that strong evaluators are less likely to make unreasonable claims on public reason and where there is a divergence the claims of the deliberating agent may turn out to be reasonable. The guiding idea here is that strong evaluators, just because they have a high regard for the ends of their life are unlikely to make excessive demands borne out of desires and appetites: it will be recalled that these are mediated through valued purposes related to the enactment of valued ways of living. Strong evaluators are less likely to be solely driven by appetites that can only be satisfied through excessive expense.

But this, it may be countered, only shifts the problem from desire to value: what if my considered values lead me to seek unreasonable opportunities for functioning? Surely strong evaluators are just that—persons who have strong beliefs concerning their own identities and purposes. As interpreted by Rawls, the role of public reason is not to dilute strongly held views but to ensure they can be developed (i.e. there are opportunities for functioning) consistent with “the idea of equal basic liberties for all free and equal citizens” (Rawls, p. 148). Thus public reason, if correctly applied, may open up opportunities for functioning—a good recent example in Britain is the introduction of civil unions for same-sex couples.

The essential point about public reason is that its role is not that of moderating strongly held views but of ensuring that they can be expressed—and enacted—in the public arena, providing that liberties of citizens are not impaired as a result. A society of strong evaluators requires a system of public reason precisely so that strong evaluation becomes a viable way of life in a society characterised by co-operation in its basic workings.

Deliberation on Career Choice

I finally want to consider how the capability approach could be used in deciding career choice. This presumably is a process that directly impacts on well-being and calls for extended deliberation (though often it is left to sheer chance). I do not wish to discuss the process through which the guidance of career choice takes place—this is an interesting, but separate, topic. Rather I wish to look, briefly, at the elements that need to feature in the deliberation from the standpoint of the agent rather than the careers adviser. Persons in this position often assume that their main needs are informational but this is only one of a number of factors which include:

-

Intrinsic Values (the kinds of functionings that play the role of key motivators)

-

Prudential Values (aspirations and the like)

-

Skillset

-

Knowledge and Understanding

-

Information about opportunities for functioning in occupational contexts

…………………………………

-

Information about job/training opportunities

The object of deliberation is to get all these elements into some kind of reflective equilibrium so that there is a congruency between the functionings in occupational contexts and the functionings picked out by intrinsic values. More specifically, occupational functionings can also deliver on intrinsic values. In addition, the skillset and knowledge (which can also be identified in terms of capabilities) need to be sufficient to enable, at least potentially, occupational functionings. At the same time, these latter need to deliver on prudential values (which is where information about job and training opportunities come in). Neglect of any one of these elements may (almost certainly will) impact on well-being. Typical, for example, is to omit reflection on intrinsic values and occupational functionings, concentrating only on prudential values, with the consequence that aspirations may be satisfied at the expense of overall well-being. To go straight to information about job opportunities (in effect not deliberating at all) is risky from the standpoint of well-being (to say nothing of the non-enhancement of one’s employability).

What is of particular note here is the need to translate skillset and knowledge into capabilities. If this is done then the way is opened up for identifying possible functioning opportunities. There will, of course, be many types of functioning that are readily associated with the skillset/knowledge combination. Creative or innovative deliberation goes further once deliberation extends to occupational functionings for it may be that hitherto unexplored opportunities for functioning are identified. Having done this, they need to be checked against intrinsic values. But it should be noted that intrinsic values need not be fixed: the process of reflective equilibrium works both ways and it may be that, through deliberation, intrinsic values are also revised and given different weightings. The process is further complicated by the fact that understanding of possible occupational functionings may well need to be experiential which means that deliberation over career choice can be, quite legitimately, a protracted process.

I conclude with a brief observation on the place of career choice (or career management) in the curriculum. Very often, this is simply left to the student to sort out with fairly minimal input from a careers adviser: the process is seen as extra-curricular. Moreover, career choice is often seen as essentially an information-driven process. But if the main arguments of this paper are valid then the development of the capability of deliberation is an essential part of well-being and deliberation over occupational choice is a particular instance of this process. It therefore follows that space in the curriculum needs to be made for career choice, from school right through to university. I am not advocating, however, careers education in the form of compulsory modules for whilst this could well suit some students there are others for whom this would be entirely unsuitable. But given the complexity underlying career choice, space for deliberation could be provided at regular intervals throughout the curriculum. It is odd that so much time and attention is devoted to the acquisition of knowledge, understanding and skills whilst crucial decisions consequent on this education (what university shall I apply for, what course should I pursue, which occupation best suits me) are often left more or less to chance.

References

Aristotle (1980). Nicomachean ethics (trans: Ross, D.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, G. A. (1993). Equality of what? On welfare, goods and capabilities. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 9–29). New York: Oxford University Press.

Griffin, J. (1991). Against the taste model. In J. Elster & J. Roemer (Eds.), Interpersonal comparisons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pettit, P. (2001). Capability and freedom: A defence of sen. Economics and Philosophy, 17, 1–20.

Rawls, J. (1999). The law of peoples. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rorty, A. (1980). Essays on Aristotle’s ethics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sandel, M. (1998). Liberalism and the limits of justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. (1985a). Moral information. Journal of Philosophy, LXXXII(4), 169–221.

Sen, A. (1985b). Well-being and freedom. Journal of Philosophy, LXXXII(4), 169–221.

Sen, A. (1985c). Freedom and agency. Journal of Philosophy, LXXXII(4), 169–221.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2002). Rationality and freedom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. (2006). Reason, freedom and well-being. Utilitas, 18(1), 80–96.

Taylor, C. (1985). Philosophical papers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Lorella Terzi and the UK Capabilities in Education Network for their comments. I should also like to thank Ortrud Lessman of the University of Hamburg for her very helpful critical comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinchliffe, G. Capability and Deliberation. Stud Philos Educ 28, 403–413 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-009-9129-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-009-9129-3