Abstract

Economists traditionally explain the nonprofit sector in terms of its market failure-correcting role. This explanation is generally recognized as being too narrow and unable to take due account of the nonprofit sector’s diversity. To fill this gap, this paper outlines a critical systems perspective on the role of the nonprofit sector. Building on the heterodox institutionalist theory, the paper argues that for-profit firms have an inherent tendency to marginalize a number of societally relevant activities. The role of the nonprofit sector is to internalize these activities and thus span the boundary between the for-profit sector and the broader society. Concurrently, the nonprofit sector may exhibit its own marginalization problems arising from its growing managerialism, professionalization and other by-products of neoliberalism. These problems constrain the ability of the nonprofit sector to internalize societally relevant activities but are potentially detectable by the sector’s internal boundary critique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades there has been a growing awareness of the societal importance of nonprofit organizations, which are seen as an increasingly useful supplement to both the public and private for-profit sectors. Nonprofit organizations, “play a variety of social, economic, and political roles in the society. They provide services as well as educate, advocate, and engage people in civic and social life” (Boris and Steuerle 2006, p. 66). The growing impact of the nonprofit sector on diverse aspects of social life across the world has been matched by significant advances in the nonprofit economics literature that explain this sector’s role in terms of correcting various types of market failures (ibid).

Yet, this type of economic explanation of the nonprofit sector has not been satisfactory to many non-economist nonprofit scholars, who have raised two major concerns. First, they maintain it is not at all clear that the diverse range of social problems addressed by the nonprofit sector, such as protecting human rights, delivering humanitarian aid, and promoting social welfare, can be attributed solely to market failures. Second, market failure theories of the nonprofit sector sidestep important motivational issues such as altruism, ideological entrepreneurship, and mission-drivenness, each of which is central to this sector’s institutional identity. As a result, these theories fail to explain how the needs of customers or citizens are linked to the actual motivation of nonprofit entrepreneurs. Without this link being made clear, the whole set of market failure theories of the nonprofit sector suffers from a fundamental deficit of plausibility.

This paper argues that a more realistic representation of the problems addressed by the nonprofit sector can be developed by utilizing ideas found in the critical systems thinking literature. Critical systems thinking questions the existing structures of wealth, status, power, and authority (Jackson 2010), and traces these structures back to the epistemological idea that cognitive limitations prevent people from seeing the full contexts of their decision making situations (Midgley 1992). Therefore, in order to make decisions, individuals must define their reference systems of concern by setting the boundaries of these systems. As Midgley (1992) argues, boundary setting necessarily involves marginalization, i.e., the placement of certain phenomena beyond the boundaries of the reference systems. Ulrich (2000) makes a similar point by grounding boundary setting in boundary judgments, i.e., factual and ethical judgments on what does and does not belong to the reference system. The central assumption of critical systems thinking is that different individuals, even when placed in similar decision making contexts, will define their respective reference systems differently. Therefore, individuals may engage in boundary critique, i.e., question and criticize each other’s boundary judgments (Ulrich 2000). If this critique is successful, they expand their reference systems by internalizing (i.e., including into these systems) some of those phenomena that had previously been marginalized. In this sense, boundary critique is a boundary spanning exercise.

While these definitions may sound somewhat abstract, they readily yield themselves to an application to the nonprofit sector context. More specifically, the existing structures of wealth, status, power, and authority (cf. Jackson 2010) are deeply embedded in the for-profit sector, which is governed by powerful vested interests (i.e., actors seeking the maintenance of the status-quo). For-profit firms will not undertake activities from which these vested interests do not stand to benefit. Accordingly, vested interests set the boundary between issues that are and are not relevant to the for-profit sector. As Midgley (1992) suggests, unemployment is one of those issues that are marginalized by vested interests embedded in the for-profit sector. Midgley proposes defining critical systems thinking in terms of questioning boundaries, and this proposal is highly suggestive of the critical systems role of the nonprofit sector. Indeed, from the critical systems perspective, the nonprofit sector can be seen as addressing issues that are marginalized by (vested interests governing) the for-profit sector. In this way, the nonprofit sector questions the boundaries set by these vested interests.

At the same time, a critical systems perspective on the nonprofit sector must examine the delineation of this sector’s own boundaries. Individual nonprofit organizations may vary in the extent to which they actually manage to address societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector. Moreover, the recent growth of managerialism and professionalization in the nonprofit sector, the rise of new public management, “risk colonization” (e.g. Rothstein et al. 2006) and other implications of the neoliberal political rationality suggest that nonprofit organizations may themselves marginalize societally relevant activities that are central to their missions. A critical systems understanding of the nonprofit sector requires a balanced view of marginalization processes that not only occur in the for-profit sector but in the nonprofit sector itself.

The critical systems rationale of the nonprofit sector is largely immune to criticisms raised against the market failure rationale. By accentuating the boundary-spanning function of the nonprofit sector, the critical systems rationale associates this sector with the ideas of user-centric design and systemic governance (McIntyre-Mills 2010a, b, c, 2006). These ideas are foreign to the neoclassical market failure approach, which defines societal problems in terms of inefficiency rather than marginalization. Elaborating on this rationale requires three major questions to be addressed, however. First, it is necessary to define the nature of the boundary-setting process practiced by vested interests governing the for-profit sector. Second, it is necessary to show how the nonprofit sector is able to question this boundary. Third, a boundary critique of the for-profit sector must be supplemented with the respective critique of the nonprofit sector. These questions are dealt with in the following three sections.

Toward a Boundary Critique of the For-Profit Sector: Insights from Heterodox Institutionalism

In the critical systems literature, the notion of boundary critique was developed by Ulrich, who understood it as the systematic employment of boundary judgments with a view to emancipating stakeholders who are ‘affected but not involved’ (cf. Ulrich and Reynolds 2010). Ulrich (2000) indeed argued that boundary critique is an essential tool for empowering citizens and thus for strengthening civil society. In the present paper however, the notion of boundary critique is used not in Ulrich’s sense of reflective practice, but rather in the sense of exploring the marginalization (i.e., boundary-setting) process inherent to the for-profit sector.

The nature of this process cannot be comprehensively examined in a single paper; yet it is possible to identify a strand of heterodox economic theory that raises important critical concerns about the operation of the for-profit sector, concerns that readily lend themselves to reconstruction in terms of critical systems thinking (cf. Valentinov 2011). These concerns stem from institutionalism, which is rooted in the writings of scholars such as Thorstein Veblen, John Commons, and Clarence Ayres (cf. Tool 2001). According to this scholarly tradition, society is a holistic entity engaged in the evolutionary process of problem-solving, which is basically about societal self-provisioning with the material means of life (ibid). The basic feature of heterodox institutionalism that makes it highly appropriate for underpinning a boundary critique of the for-profit sector is a critical approach toward markets. In the words of Samuels (1995, p. 580), “a principal theme of [heterodox] institutional economics has been that the economy is more than the market.”

The heterodox institutionalist criticism of the market, and of the for-profit sector, is framed by the notion of the “institutionalist dichotomy” which, in technical terms, highlights the contrast between progressive and dynamic “instrumental value”, on the one hand, and static and backward-looking “pecuniary value”, on the other (Veblen 1994; Tool 2001). For the present context, this dichotomy accentuates the inconsistency between individual profit seeking and the interests of society at large. The latter interest is defined in terms of broadly understood commonalities of human interests and is exemplified by Veblen’s (1994, p. 61) references to “usefulness as seen from the point of view of generically human”, “enhancing human life on the whole”, “furthering the life process taken impersonally”, an Ayresian idea of technological continuum, and a Deweyian criterion of increasing the meaning of experience. At the same time, Veblen associates individual profit seeking with the pursuit of differential advantage, the use of invidious distinctions, and social stratification. In Veblenian work, the differential advantage orientation of business behavior epitomizes the tendency of businessmen to relegate the interest of society as a whole beyond the boundaries of their concern. As a result, businessmen become disinterested in societally important issues related to social care, education, culture, civic advocacy, and environmental protection. While crucially important for the quality of community life, these issues are marginalized by the for-profit sector because they bring little or no individual pecuniary gain.

Institutionalists proposed addressing these marginalized issues through public action in the various forms of “indicative” or “democratic planning” supported by scientific expertise (Tool 2001). The apparent problems with public action are its susceptibility to bureaucratic and political opportunism and its lack of access to local knowledge and initiative. As shown in the next section, these problems arise to a lesser degree if these marginalized issues are addressed by the nonprofit sector.

The Meaning of the Nonprofit Sector

While generating excellent insights into the limitations of the profit motive and of the for-profit sector, the heterodox institutionalist literature generally fails to pay attention to the nonprofit sector. This is an important omission since it obfuscates the potential synergies and complementarities between the sectors. According to the data of Anheier and Salamon (2006), and as argued above, the most important activities of the nonprofit sector worldwide are indeed those that have been marginalized by for-profit firms, i.e., social care, education, culture, civic advocacy, and environmental protection. Thus, the societal role of the nonprofit sector can be seen in reconfiguring the allocation of societal resources, as it evolves in the for-profit sector, in a way that meets those human needs that extend beyond the concerns of individual businessmen.

From the critical systems perspective, the institutionalist proposal of public action to internalize societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector boils down to substituting one type of system boundary for another type, without sufficient critical awareness of this substitution. More specifically, the boundary between the for-profit sector and the broader society is replaced by the boundary between citizens and public officials on the one hand, and scientific experts on the other. The nonprofit sector is specifically geared towards involving citizens who offer their initiative and local knowledge. By combining private initiative with mission orientation, the nonprofit sector fully corresponds to McIntyre’s (McIntyre-Mills 2010a, b, c) case for the marriage between decentralization and the pursuit of common societal interests. McIntyre (ibid) illustrates this case with research utilizing narratives told by Aboriginal service users and Aboriginal service providers in Australia in order to solve complex societal problems such as unemployment, alcohol abuse, domestic violence, and homelessness. While all these problems are marginalized by the for-profit sector, McIntyre (ibid) emphasizes that the public sector alone is likewise ill-equipped to deal with them, primarily in view of its bureaucratic and compartmentalized behavior. The reported research revealed the advantages of user-centric design in combining the pursuit of common good with decentralized “steering from below”, and it is this combination that is enabled by the nonprofit sector.

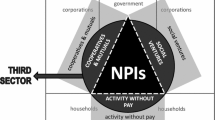

Thus, the basic feature of the boundary-spanning function of the nonprofit sector is that, while internalizing the societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector, the nonprofit sector does not require the demolition of the boundaries set by the latter. The meaning of this feature can be conveniently illustrated in terms of Midgley’s (1992) distinction between primary and secondary boundaries, the former of which demarcates the reference system from the broader relevant environment, while the latter demarcates the broader relevant environment from the irrelevant, and invisible, environment. Midgley (ibid) employed this distinction to provide operational meaning to the notion of marginalization (which, in the present context, refers to the marginalization of societally relevant issues). Midgley (ibid) further argued that the conscious differentiation between primary and secondary boundaries poses the ethical choice between retaining the primary boundary and disbanding it, i.e., pushing it to the limits of the secondary boundary. The nonprofit sector presents a third alternative which is missing in Midgley’s framework; it entails retaining the primary boundary (which, in the present context, corresponds to the for-profit sector). Yet the option likewise foresees the internalization of various segments of the marginalized area through the activities of various individual nonprofit organizations.

In other words, given a well-functioning nonprofit sector, the for-profit sector is largely relieved of the ethical pressure of internalizing marginalized societal issues. At the same time, the internalization of these issues by nonprofit organizations does not make these organizations ethically overloaded, as these organizations pursue missions that can be formulated sufficiently narrowly to prevent ethical conflicts. For example, Steinberg (2006) identifies two major roles of the nonprofit sector that are not accounted for by the neoclassical market failure approach. One role is to restore the fair and equitable treatment of vulnerable people [exemplified by labor unions, mutual benefit and cooperative organizations, and various types of service providers (cf. Salamon 2001)]. The other role is to engage in expressive and affiliative activities [examples include advocacy organizations, social and fraternal organizations, political organizations, and possibly churches (cf. Salamon 2001)]. The missions pursued by all these organizations would likely conflict with profit-making goals, and would even possibly conflict with each other if pursued by a single organization. These ethical conflicts, however, do not occur precisely for the reason that individual nonprofit organizations are free to formulate and pursue missions that are sufficiently narrowly focused. In this way, the intra-sectoral organizational differentiation of the nonprofit sector facilitates the overall internalization of those societal issues that are marginalized by the for-profit sector.

Toward a Boundary Critique of the Nonprofit Sector

In the proposed critical systems perspective, the paradoxical feature of the nonprofit sector is that it itself inevitably involves a boundary-setting process. As both Midgley (1992) and Ulrich (2000) point out, boundary setting is a general cognitive prerequisite for identifying a system of concern to the respective decision-maker. While the nonprofit sector internalizes the societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector, it faces the challenge of defining its own boundary. In fact, in view of the considerable complexity of the societal issues involved, some leeway must remain in the actual boundary-setting processes within the nonprofit sector, a leeway that leads to potential variations in the extent to which individual nonprofit organizations actually succeed in counteracting the marginalization induced by the profit motive. Some of these variations are certainly idiosyncratic to specific individual nonprofit organizations, but some can be traced to the broader political regime of neoliberalism and the regulatory state that heavily shapes the institutional environment of the nonprofit sector in the contemporary Western world. The following subsections discuss the ways in which the broader institutional environment affects the internalization potential of the nonprofit sector.

The Neoliberal Context

The main ideological thrust of neoliberalism is the market-driven approach to economic and social policy based on neoclassical economics that stress the efficiency of private enterprise, liberalized trade and relatively open markets. Neoliberals seek to maximize the role of the private sector in determining the political and economic priorities of the state.Footnote 1 The outcome of this is a profound understanding of political power. According to Rose (1999), political power is no longer seen as concentrated in the institutions of the state; it is increasingly understood as dispersed among complex networks that encompass both state and non-state actors. The changed perception of political power underpins the shift from government to governance (Marsden and Murdoch 1998), basically meaning “the development of governing styles in which boundaries between and within public and private sectors have become blurred” (Stoker 1998, p. 17). In the political arena, the shift from government to governance is reflected in the emergence of a new regulatory state that combines privatization with regulatory growth (Braithwaite 1999). In a neoliberal regulatory regime, it is not sufficient to ensure the accountability of the state to non-state actors. Rather, it is essential to establish genuine public–private governance that shifts political power from the former to the latter, particularly in view of the declining legitimacy of the modern welfare state (ibid).

The neoliberal political rationality is accordingly constructed so that it contains a significant role for the nonprofit sector. Rose (1996, p. 331) explains this role in terms of the so-called “advanced liberal” trend of “the social” to “the community”, “as a new territory for the administration of individual and collective existence”. Along similar lines, Osborne and Gaebler (1992) explore the notions of community-owned, mission-driven and customer-driven government, which is concerned with “steering rather than rowing”. The government’s concentration on “steering” activities requires it to delegate “rowing” (i.e., service delivery) to non-state actors, including nonprofit organizations. Indeed, as Ayres and Braithwaite (1992) have shown, governments can outsource even regulatory activity by promoting voluntary self-regulation which, again, is institutionally anchored in business associations and other types of nonprofit organizations.

Yet in overall terms, neoliberal rationality is a mixed blessing for the nonprofit sector. While the neoliberal government seeks close collaboration with this sector, it imposes regulatory requirements that can weaken the sector’s potential to fully internalize the societal issues marginalized by for-profit firms. These requirements arise largely in connection with the governance of risk, specifically with extensive attempts at risk management (cf. Power 2004). As O’Malley (2004) points out, it has become common knowledge among social theorists that late modernity is associated with risks which are often too complex to be effectively managed by the state and thus require dispersed governance. However, according to Rothstein et al., risk likewise acts as “an organizing idea for decision-making in modernity,” and concurs with the new public management movement that promotes: bureaucratic protocolization; defensiveness; blame avoidance; erosion of trust; and excessive reliance on economic thinking as embodied in the for-profit sector (Rothstein et al. 2006). The specific adverse effects of this “organizing idea” on the nonprofit sector are explored in the following subsections.

The Problems

The main implication of risk governance for the nonprofit sector can be well captured by the notion of risk colonization, proposed by Rothstein et al. (2006). These authors understand risk colonization as the tendency of risk to increasingly define the object, methods, and rationale of regulation (ibid, p. 93). According to Rothstein (2006), risk colonization arises in response to the pressure to rationalize practical limits of governance under conditions of rising accountability requirements. The key consequence of risk colonization is the decoupling between societal risks and institutional risks, which potentially leads to institutional risk management efforts at the expense of managing real societal risks. In a way, the dichotomy between societal risks and institutional risks is reminiscent of the abovementioned institutionalist dichotomy between individual profit-seeking and the interest of society at large. Along the lines of the institutionalist dichotomy, the decoupling between societal risks and institutional risks results in sacrificing larger societal issues to organizational imperatives.

More specifically, when confronted with significant institutional regulatory risks, nonprofit organizations are likely to engage in blame avoidance behavior, usually summarized under the rubrics of managerialism, professionalization, and commercialization of the nonprofit sector. The adverse consequences of this behavior for mission achievement have been particularly well documented in the fields of community care and human services. For example, Parton (1998) argues that in these fields, the difference between the defensible decision and the right decision becomes particularly pronounced. Moreover, managerialism and professionalization are often accompanied by formal audits that replace the trust “…once accorded to professionals both by their clients – now users and customers – and the authorities which employ, legitimate and constitute them” (ibid, p. 20). In the same vein, Green and Sawyer (2008) report that community service organizations react to growing institutional risks by adopting corporate risk management methods which unavoidably fail to match the complexity of community care relationships. More than that, the very field of social care is increasingly colonized by for-profit firms claiming that competitive pressures force them to provide services that are even more person-centered than those delivered by traditional nonprofit organizations.

Generally, risk management is recognized as a theory that favors experts and excludes citizens, thus reducing the scope for citizen participation in the nonprofit sector. Scott (2007) argues that risk management involves a technocratic discourse that substitutes the calculation of risks for genuine problem solving. Furthermore, the very technocratic nature of this discourse serves to conceal implicit value orientations that potentially reflect vested interests and coercive relationships (ibid). In view of its tendency to constrain citizenship participation, risk discourse is unsuitable for discussing quality of community life, which is the fundamental concern of the nonprofit sector (ibid). Thus, nonprofit organizations, while seeking to correct the marginalization problems endemic to the for-profit sector, may become colonized by risk discourse to the point of replicating and perpetuating the marginalization patterns enforced by the for-profit corporate elite.

A further possible problem resides in the excessive dependence of nonprofit organizations on public funds. Smith and Lipsky (1993) have long identified a fundamental change in nonprofit service delivery involving the transformation of nonprofit organizations into “vendors” and “agents of the state”. According to the authors, this transformation deprives nonprofit organizations of their traditional roles as sites for civic participation and the inculcation of democratic values. As vendors of public services, nonprofit organizations inevitably run the risks of bureaucratization, professionalization, politicization, and loss of autonomy. In the words of Clemens (2006, p. 210), “…the larger and richer and more formalized the organization, the fewer the opportunities for participatory governance and democratic socialization of members (to the extent that they exist at all).” Both risk colonization and excessive dependence on governmental money lead to nonprofit organizations becoming increasingly similar to their for-profit and public counterparts, thus causing the erosion of intersectoral boundaries.

The Opportunities

The outlined effects of the neoliberal political rationality on the nonprofit sector clearly diminish the sector’s ability to internalize the societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector. These effects highlight the potentially contestable nature of the conceptual boundaries that both for-profit and nonprofit organizations need to delineate in order to distinguish themselves from the environment. Yet the major difference between the for-profit and nonprofit sectors is that only the nonprofit sector may incorporate issues that happen to be marginalized. It has been shown above that the nonprofit sector is required to counteract the marginalization process endemic to the for-profit sector. While the nonprofit sector may likewise be subject to similar marginalization problems due to risk colonization and other implications of neoliberalism, it is only the nonprofit sector itself that is able to counteract these problems. Along this line, Kemshall (2002) describes several cases of social workers and other nonprofit professionals consciously resisting the trends of growing managerialism and professionalization. Further, Rose (1994) documents the role of consumer and user organizations in questioning the expertise implicated in risk management. Other scholars emphasize that risk governance may in fact facilitate the internalization function of the nonprofit sector. Titterton (2005) developed a positive risk-taking approach for social service organizations that is used to help them better internalize the concerns of vulnerable people; Scott (2007) argued that risk awareness may in some cases bolster citizen participation, e.g. in the field of consumer rights.

The main reason for hoping that the nonprofit sector may stand up to the challenges posed by neoliberal political rationality is the value this rationality attaches to devolved governance, of which the nonprofit sector is a major variety. The new regulatory state needs a strong nonprofit sector that is capable of effectively embodying voluntary self-regulation and solving social problems. This point was clearly made by Osborne and Gaebler (1992), who posit that it is only those communities supported by their respective nonprofit organizations that can solve serious social problems. Therefore, while the government is interested in outsourcing service delivery to nonprofit organizations, it likewise maintains an interest in these not degenerating into “vendors” in the sense of Smith and Lipsky (1993).

The practical implication of this argument for nonprofit organizations is their need to continually engage in the internal (intra-organizational and intra-sectoral) boundary critique in order to develop what Ulrich (2000) calls “civil competencies”. In the present context, “civil competence” means the actual ability of nonprofit organizations to fully incorporate their mission-related societal issues and expose the adverse effects of their own managerialism and professionalization. It is only to the extent that the nonprofit sector succeeds in its internal boundary critique that it can be an effective institutional device for internalizing the societal issues revealed by the boundary critique of the for-profit sector. The boundary critique is thus essential for both sectors; it helps to disclose the processes of marginalization and test the effectiveness of the counteracting internalization mechanisms. More specifically, boundary critique helps reveal the societal marginalization potential of the profit motive and ensure that this potential is adequately compensated by the nonprofit sector.

Concluding Remarks

The critical systems literature draws attention to the importance of questioning and spanning boundaries that circumscribe the relevant social and conceptual systems in view of the need to address overarching common challenges (cf. Mcintyre-Mills 2010a, b, c, 2006). The contribution of the present paper is that it points out the boundary-spanning role of the nonprofit sector, and explains this role in terms of the inherent tendency of for-profit firms to marginalize a number of societally relevant activities beyond the boundaries of their concern. Since the profit motive is at the root of this marginalization (as follows from the heterodox institutionalism), the nonprofit orientation is the basic feature of nonprofit organizations that enables their boundary-spanning and internalizing role.

There is, however, no guarantee that this role will be automatically fulfilled. Nonprofit organizations inevitably run the risk of failing to fully internalize societal issues marginalized by the for-profit sector, a risk that is potentially reinforced by the rise of neoliberalism and the new regulatory state. Most importantly, the growing managerialism and professionalization of nonprofit organizations detract from their ability to be effective community problem-solvers, even though this ability is largely presupposed by the neoliberal political rationality. It is therefore essential that the boundary critique of the for-profit sector is supplemented by the respective critique of the nonprofit sector. The latter critique thus becomes a prerequisite for the nonprofit sector’s ability to span the boundaries set by the profit motive.

Notes

I am grateful to one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing this out.

References

Anheier HK, Salamon LM (2006) The nonprofit sector in comparative perspective. In: Powell WW, Steinberg R (eds) The nonprofit sector: a research handbook. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 89–114

Ayres I, Braithwaite J (1992) Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press, New York

Boris ET, Steuerle CE (2006) Scope and dimensions of the nonprofit sector. In: Powell WW, Steinberg R (eds) The nonprofit sector: a research handbook. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 66–88

Braithwaite J (1999) Accountability and governance under the new regulatory state. Aust J Public Admin 58:90–97

Clemens E (2006) The constitution of citizens: political theories of nonprofit organization. In: Powell WW, Steinberg R (eds) The nonprofit sector: a research handbook. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 207–220

Green D, Sawyer A-M (2008) Risk, regulation, integration: implications for governance in community service organisations. Just Policy 49:13–22

Jackson MC (2010) Reflections on the development and contribution of critical systems thinking and practice. Syst Res Behav Sci 27:133–139

Kemshall H (2002) Risk, social policy and welfare. Open University Press, Buckingham

Marsden T, Murdoch J (1998) Editorial: the shifting nature of rural governance and community participation. J Rural Stud 14:1–4

McIntyre-Mills JJ (2006) Systemic governance and accountability: working and re-working the conceptual and spatial boundaries. Springer, New York

McIntyre-Mills JJ (2010a) Participatory design for democracy and wellbeing: narrowing the gap between service outcomes and perceived needs. Syst Pract Action Res 23:21–45

McIntyre-Mills JJ (2010b) Wellbeing, mindfulness and the global commons. J Conscious Stud 17:44–72

McIntyre-Mills JJ (2010c) Representation, accountability and sustainability. Cybern Hum Knowing 17:51–79

Midgley G (1992) The sacred and profane in critical systems thinking. Syst Pract 5:5–16

O’Malley P (2004) Risk, uncertainty and government. The Glasshouse Press, London

Osborne D, Gaebler T (1992) Reinventing government: how the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Parton N (1998) Risk, advanced liberalism and child welfare: the need to rediscover uncertainty and ambiguity. Br J Soc Work 28:5–27

Power M (2004) The risk management of everything: rethinking the politics of uncertainty. DEMOS, London

Rose N (1994) Expertise and the government of conduct. Stud Law Politics Soc 14:359–367

Rose N (1996) The death of the social? refiguring the territory of government. Econ Soc 25:327–356

Rose N (1999) Powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rothstein H (2006) The institutional origins of risk: a new agenda for risk research. Health Risk Soc 8:215–221

Rothstein H, Huber M, Gaskell G (2006) A theory of risk colonization: the spiralling regulatory logics of societal and institutional risk. Econ Soc 35:91–112

Salamon LM (2001, reprint of 1999) Scope and structure: the anatomy of America’s nonprofit sector. In Ott JS (ed) The nature of the nonprofit sector. Westview Press, Boulder, pp 23–39

Samuels WJ (1995) The present state of institutional economics. Camb J Econ 19:569–590

Scott DN (2007) Risk as a technique of governance in an era of biotechnological innovation. In: Law Commission of Canada (ed) Risk and trust: including or excluding citizens?. Fernwood Press, Black Point, pp 23–56

Smith SR, Lipsky M (1993) Nonprofits for hire: the welfare state in the age of contracting. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Steinberg R (2006) Economic theories of nonprofit organizations. In: Powell WW, Steinberg R (eds) The nonprofit sector: a research handbook. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 117–139

Stoker G (1998) Governance as theory: five propositions. Int Soc Sci J 155:17–28

Titterton M (2005) Risk and risk taking in health and social welfare. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London

Tool MR (2001) The discretionary economy: a normative theory of political economy. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Ulrich W (2000) Reflective practice in the civil society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflect Pract 1:247–268

Ulrich W, Reynolds M (2010) Critical systems heuristics. In: Reynolds M, Holwell S (eds) Systems approaches to managing change: a practical guide. Springer, Berlin, pp 243–292

Valentinov V (2011) The meaning of nonprofit organization: insights from classical institutionalism. J Econ Issues 45:901–915

Veblen T (1994) The theory of the leisure class. Dover Thrift Editions, Toronto

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to several anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. This research has been supported by the Volkswagen Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valentinov, V. Toward a Critical Systems Perspective on the Nonprofit Sector. Syst Pract Action Res 25, 355–364 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-011-9224-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-011-9224-6