Abstract

There is a large literature on the role of nonprofit enterprises within society. This literature typically views nonprofits as either substitutes for government enterprises or complements to, and even necessary extensions of, these government efforts. While this literature has improved our understanding of the role and importance of nonprofit social enterprises, how social entrepreneurs identify opportunities, allocate resources, and adapt to changing circumstances has been relatively underexplored. Efforts to fill this gap within Austrian economics have categorized nonprofits and identified the limitations of calculation and coordination in the nonprofit sector and the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful nonprofit enterprises. This strand of literature focuses on the differences between economic calculation in for-profit enterprises and decision making in nonprofit enterprises. We argue that another meaningful aspect to determining the ability of nonprofit enterprises to coordinate plans is whether they are structured more like private enterprises and public enterprises. These insights from Austrian economics shed light on why some nonprofits are more effective than others at achieving social goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nonprofit social enterprises, or voluntary organizations with social missions, have a long history of providing goods and services to their communities.Footnote 1 For example, churches often provide meals, educational programs, and social spaces for the youth and elderly in their congregations. Similarly, activist groups often advocate on behalf of the disadvantaged members of their community. Rather than pursuing profits by directly selling their goods and services to consumers in the market, these organizations pursue social goals by collecting donations and charging little to no fees to end users. These social enterprises “succeed” when they are able to attract donations and volunteers, to attract nonpaying recipients and even paying customers for the goods and services they provide, and to expand their operations over time.Footnote 2

The general success of nonprofits in addressing the needs of community members that are inadequately serviced by public or commercial enterprises has led scholars to stress the importance of civil society and argue for expanding the role of nonprofits. For instance, de Tocqueville ([1835] 2012) observes that civil associations permeated the American landscape in the nineteenth century. Because associations were so prevalent, according to de Tocqueville, early Americans studied and engaged in the art of association and viewed associations as a viable means for attaining their joint ends. Cornuelle ([1965] 2011) argues that nonprofits (or what he calls the independent sector) should and do compete with governments in the provision of goods and services in a wide variety of areas, including education, healthcare, and welfare. Likewise, Weisbrod (1988) focuses on the under-provision of public goods to heterogeneous populations and argues that nonprofit organizations are a solution to both market failure and government failure.

While scholars of this vein see nonprofits as primarily alternatives to and substitutes for government enterprises that provide goods and services, others point to the limitations of nonprofits and view them as complements to, and even necessary extensions of, government efforts. Salamon (1981, 1987, 1995, 2003), for instance, argues that the voluntary sector can fail just like markets and governments, and that social goals are more likely to be met when nonprofits partner with government. Specifically, he explores the role of government funds going to nonprofits, who then implement welfare programs, as a way to promote and expand what he calls third-party government. Acs (2013) sees philanthropy as a necessary complement to government action that helps remedy market failure as well as encourage technological innovation (especially in the areas of education, science, and medicine) and spur productivity gains and economic growth.Footnote 3

Such scholarship has stressed the importance of nonprofit enterprises in society. This literature has improved our understanding of the role and importance of nonprofit social enterprises. However, how the social entrepreneurs—who drive nonprofits—identify opportunities, allocate resources, and adapt to changing circumstances as well as how the institutional setting they operate in affects their ability to access knowledge and adapt has been relatively underexplored in the literature. Boettke and Prychitko (2004) identify this issue and argue that an Austrian approach to the study of nonprofits, grounded in a critique of neoclassical economics as well as an emphasis on economic calculation and comparative institutional analysis, would fill this gap in the literature.

Since their contribution, a handful of Austrian economists have delved into how nonprofits should be categorized, the limitations of calculation and coordination in the nonprofit sector, and the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful nonprofit enterprises. Some scholars (such as Boettke and Prychitko 2004; Boettke and Coyne 2009; Aligica 2015) have relied on the seminal work within Austrian economics on the impossibility of socialist calculation and focused on the difficulty of engaging in economic calculation in non-market settings. From this view, nonprofits are similar to governments in that they lack the knowledge transmission mechanism of market prices and the feedback mechanism of profit and loss. While they have access to “proxies for calculation,” they are necessarily inferior to those of the market (Boettke and Prychitko 2004: 22). As such, the nonprofit sector—much like the government—is less likely to correct errors and improve over time than the market. Other scholars have studied various nonprofit endeavors and argued that, while lacking many of the characteristics of enterprises in commercial settings, they may have the ability to coordinate plans and bring about social progress in ways that governments cannot (Chamlee-Wright 2004, 2010; Chamlee-Wright and Myers 2008; Storr et al. 2015). These scholars argue that the mechanisms available to nonprofits—such as reputation and competition for donors, volunteers, and customers—can and do enable knowledge discovery and social learning, and therefore, can direct nonprofits toward better coordination over time.

While there are similarities and differences between economic calculation in for-profit enterprises and decision making in nonprofit enterprises, the distinction is not quite as stark as they might first appear. While there is no doubt that entrepreneurs in an unhampered market enjoy a privileged epistemic position compared to actors in non-market settings (Boettke and Prychitko 2004; Boettke and Coyne 2009; Skarbek 2012), the theoretical distinction between the various feedback mechanisms and guides for action in the market and nonprofit sectors are often overstated when examining actual individual entrepreneurial actions in the real world (Chamlee-Wright 2004, 2010; Storr et al. 2015). In order to more fully understand the ability of real-world nonprofits to coordinate plans in order to achieve social goals, we argue that it is important to more completely examine the institutional setting nonprofits operate within. In addition to understanding the limits to calculation within nonprofit enterprises, the relative success or failure of the proxy mechanisms available to nonprofits is determined by whether nonprofit enterprises are more private (or voluntary) or public (or involuntary) in nature. Private commercial and social activity, pursued through decentralized enterprises and disciplined by the actions of donors, volunteers, customers, investors as well as by the competition between private enterprises can and is likely to lead to social learning and social progress over time. Public activity that is centralized and protected from competition is less likely to be sensitive to changing circumstances or to lead to the coordination of plans, social learning and social progress over time. This distinction between private/decentralized and public/centralized activities opens the door for studying how nonprofits can bring about plan coordination and achieve social goals, and how interventions into nonprofit activity can distort their plans and negatively affect outcomes.Footnote 4

This paper contributes to two important literatures. First, it contributes to the Austrian literature on economic calculation in non-market settings by incorporating the distinction between private and public institutional structures in the assessment of the ability of nonprofits to coordinate their plans and achieve social goals. Second, it contributes to the social entrepreneurship literature by highlighting the insights of an Austrian approach to the study of social enterprises. This approach focuses on the limits as well as the potential of social entrepreneurs to solve social problems and bring about social transformations. It also offers a way of assessing why and when certain social enterprises are likely to outperform others.

The paper proceeds as follows. Next, Section II reviews the nonprofit literature in the Austrian tradition. Section III, then, argues that the distinction between private and public enterprises is a meaningful and useful approach for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of real-world nonprofit enterprises. We use this approach to examine Habitat for Humanity International, a nonprofit organization that aims to promote affordable homeownership among impoverished populations. And, Section IV concludes.

2 The distinction between commercial and social enterprises

Much of the literature on nonprofit social enterprises highlights both the importance of nonprofits as complements and/or supplements to commercial and public enterprises (see, for instance, de Tocqueville [1835] 2012; Cornuelle [1965] 2011; Weisbrod 1988; Lohmann 1992; Salamon 1981, 1987, 1995, 2003; Acs 2013).

de Tocqueville ([1835] 2012) famously observed the important role that associations play within democratic societies. He (ibid.: 902) states,

Americans of all ages, of all conditions, of all minds ... constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which they all take part, but also they have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, serious ones, useless ones, very general and very particular ones, immense and very small ones; Americans associate to celebrate holidays, establish seminaries, build inns, erect churches, distribute books, send missionaries to the Antipodes; in this way they create hospitals, prisons, schools. If, finally, it is a matter of bringing a truth to light or of developing a sentiment with the support of a good example, they associate.

These association, de Tocqueville observed, were the ways in which Americans voluntarily addressed common goals. However, he also worried that government activities would crowd out thriving associations. de Tocqueville (ibid.: 900) warns, “the more [government] puts itself in the place of associations, the more individuals, losing the idea of associating, will need to come to their aid. ... The morals and intelligence of a democratic people would run no lesser dangers than their trade and industry, if the government came to take the place of associations everywhere.”

Cornuelle ([1965] 2011) worried that modern government had indeed crowded out associational life and was also not providing the intended results. He (ibid.: 14) states, “Honest, well-intentioned men who once championed the federal alphabet agencies have had time to measure promise against performance. And they see a widening gap between what government says it can do and what it gets done.” Likewise, he saw that nonprofits were underappreciated: “We ignore the institutions which once played such a decisive part in the society’s vibrant growth. … It is a distinct, identifiable part of American life, not just a misty area between commerce and government” (ibid.: 26). Therefore, Cornuelle argued that the independent sector could, and should once again, perform a critical societal function.Footnote 5 While nonprofits lack the scope and scale of government, they can provide competition to and differentiation from government efforts.

Further, Cornuelle (1983) argued that nonprofits provide opportunities that markets and governments do not. He (ibid.: 158) claims that,

The sector provides platforms where unconventional views can be explored, debated, and offered for consideration to the larger public … The independent sector constitutes this society’s cutting edge. It is the sector to which even the alienated can belong, and in which the powerless can begin to build a sense of power. Perhaps most important of all, it has provided the principal channel by which any citizen, regardless of age, race, affluence, or ability, can act on his concerns in any peaceful way he chooses.

Weisbrod (1988) similarly viewed nonprofits as alternatives to government-provided good and services, particularly when preferences and needs are heterogeneous. For Weisbrod, nonprofits are alternatives to both market and government failure.

Salamon (1987, 1995, 2002, 2003) counters Weisbrod’s conception of nonprofits as a response to government failure. He observes that widespread partnership between nonprofits and government has been prevalent since the 1960s and 70s, and has resulted in growth and development of the nonprofit sector. This is not a strange phenomenon, but rather, he argues, a necessary development in order to better provide welfare services. For Salamon (1981, 1987), this form of “third-party government” is a way to decentralize service provision while still maintaining a centralized source of funding and strategy. Through “grant-in-aid programs … the federal government performs a managerial function but leaves a substantial degree of discretion to its nongovernmental, or nonfederal, partner” (Salamon 1987: 37). This approach to welfare provision supports the American emphasis on federalism, and the diversity of views of the role and scope of government. He states (ibid.: 37), “Third-party government has emerged as a way to reconcile these competing perspectives, to increase the role of government in promoting the general welfare without unduly enlarging the state’s administrative apparatus.” Viewed this way, government supports the nonprofit which is likely to fail due to amateurism as well as its inability to scale up and to provide universal goods and services (ibid.).

Government-nonprofit partnerships, and their strengths and weaknesses, are widely studied (see Brinkerhoof and Brinkerhoff 2002; Skelcher 2007; Smith and Gronbjerg 2006). For example, Young (2000) discusses how theories of nonprofits of substitutes, complements, or adversaries with government are all prevalent in the real world, in America and across the globe. Gazley and Brudney (2007) find that partnership occurs because nonprofits seek funding security and because governments seek expertise and capacity building. Gazley (2010) finds that formal and extended partnerships lead government officials to perceive nonprofit activities as more effective, even though actual effectiveness is correlated to shared missions and commitment. And, MacIndoe (2013) surveys nonprofit executive directors and finds that partnerships with local government is correlated with scope and scale, is an effort to reduce transaction costs, and is reinforced by dependence on government funds.

The nonprofit literature has highlighted the importance of the nonprofit social enterprises and advanced economic concepts toward the study of nonprofits, such as public goods, stakeholders, trust, organizational structure and behavior, and market, government, and nonprofit failure (for example, see Rose-Ackerman 1986; Anheier and Ben-Ner 2003). They examine capacity building, funding restrictions and opportunities, accounting practices, and outcome measurement (see Richmond et al. 2003; Wing 2004; Watson Bishop 2007; Carmen and Fredericks 2010; Stater 2010). However, the literature has not tended to focus on how the social entrepreneurs identify opportunities, allocate resources, and adapt to changing circumstances nor how the institutional setting they operate in impact their ability to access knowledge and adapt.

Boettke and Prychitko (2004) identified this gap in the literature and advocated for an Austrian approach to the study of nonprofits.Footnote 6 Using the lessons from the socialist calculation debate, they argue that nonprofits cannot engage in economic calculation and, therefore, are hampered in their ability to coordinate plans.Footnote 7 While nonprofits have access to market prices and can evaluate their activities, because they do not generally price their output, they have no rational basis to determine whether or not they are using their resources effectively (i.e. to coordinate their plans). As Boettke and Prychitko (ibid.: 22) note, “although nonprofits can undertake measurements, and, if encouraged, a rational assessment of their outcomes (using both quantitative and qualitative means), they have no way of calculating the realized results against the expected results.” They (ibid.: 22) argue that, “the absence of such calculation implies that entrepreneurs who create and executives who manage nonprofit firms may indeed be handicapped in their ability to demonstrate the efficiency or inefficiency of their activities.” Rather than seeking to determine the success of nonprofits by efficiency standards (such as Pareto-optimality), the “more broad accomplishment of plan fulfillment must suffice” (ibid.: 25). From this view, “issues of trust, reputation, satisfaction, and so on might serve as effective guides to action” (ibid.: 22) when calculation is absent. This is program effectiveness (i.e. the extent to which program results fall short of, meet, or exceed program goals). These measures only determine if nonprofits are utilizing their resources effectively (i.e. they are using them in ways that advance their program goals), not whether they are utilizing toward their most valued use. While social enterprises are not ships adrift without compasses, the captains of these vessels are epistemically disadvantaged vis-à-vis their counterparts in the commercial sector.Footnote 8

Boettke and Coyne (2009: 43) similarly argue that the central difference between social and commercial enterprises is that social enterprises are not guided and disciplined by market prices, profit, and loss and, so, do not have the ability to engage in economic calculation. As they (ibid.: 43) write, “the key difference between social entrepreneurship and market entrepreneurship is that the latter is driven by the desire for profit while the former is not.” This, they explain, puts social entrepreneurs at a disadvantage compared to commercial entrepreneurs. While the for-profit sector can follow the bright signposts of profits and losses, the nonprofit sector must find and follow less clear signals. One imperfect mechanism that disciplines social endeavors is reputation. As Boettke and Coyne (ibid.: 45) explain, “in the absence of this mechanism [of profit and loss], the non-market sector relies on the disciplinary devices most appropriate for that sort of interaction, namely reputation … The only way that the social entrepreneurs can decide between competing projects is to limit their activities to those initiatives that can be directly monitored and disciplined on the basis of reputation.” At best, the social entrepreneur can focus on those activities that they believe are likely to improve their reputation and can use how the results of their efforts are viewed by relevant stakeholders to determine whether to continue along or shift focus. Boettke and Coyne (ibid.) go on to argue that the more closely a social entrepreneur follows donor-intent, the more effective they will be at accomplishing their goals, and emphasize the importance of reputation in ensuring that social entrepreneurs fulfil the intentions of their donors.

Although social entrepreneurs can rely on reputation to guide action, the mechanism is necessarily inferior to prices and profits and losses. As Boettke and Coyne (ibid.: 47) conclude,

It is important to note that reputation collateral is not a substitute for economic calculation. Absent monetary calculation we cannot be confident that the decision of donors to provide monetary support to social entrepreneurs is an efficient allocation of resources. Likewise, we cannot be confident that the mistakes of social entrepreneurs will tend to be self-correcting as in private markets. Acting in the nonmarket setting, whether it is giving by donors or the undertakings of social entrepreneurs, means that people are acting outside the feedback mechanisms of prices and profit and loss. Given this, the best we can do is to find disciplinary devices that ensure that social entrepreneurs tend to meet the desires of donors.

Nonprofits are imperfect and severely limited enterprises. There is little reason to be confident that social entrepreneurs will use resources effectively and that social entrepreneurs will be able to identify and correct for errors and changes when they occur. Viewed in this way, nonprofit activity seems likely to disappoint.

While this viewpoint sheds light on the real challenges and limitations that face nonprofits by situating them outside of the market setting and alongside the public sector, it does not necessarily provide a framework for determining if and how social entrepreneurs differ meaningfully from public entrepreneurs. Both social and public entrepreneurs cannot engage in economic calculation because they do not price their outputs and are not guided by the feedback of profit and loss. The manager of a nonprofit nor a senior bureaucrat in a public agency can use the resources that are available to them through donations or taxation in ways that their constituencies prefer. But, neither can be certain that they are not wasting resources (i.e. spending more for programs than the value those programs create). Regarding their capacity to engage in economic calculation, they are more similar than different.

While individually, social and public entrepreneurs may face similar challenges, their challenges are magnified when intermingled. Boettke and Prychitko (2004: 28) observe that when social enterprises gain access to public funds, they are “transformed into rent-seeking entities dependent on tax finance rather than the voluntary contributions of individual donors.” And, it can be argued that partnership between social and public enterprises can further distort the signals available to nonprofits. Boettke and Prychitko (ibid.: 28) posit that, “As client-partners of the state, many contemporary not-for-profit and nonprofit organizations provide goods and services, but no longer sustain the necessary feedback and disciplinary to ensure that good intentions are channeled in directions that generate desired results.” This approach challenges the notion that nonprofits should be complements to and partners with the public sector, contributes to the notion that nonprofits may be substitutes for government activity, and challenges the notion that nonprofits can systematically provide social goods and services that benefit society compared to the market.Footnote 9 However, a more nuanced distinction between the capabilities of nonprofits and government requires more than determining their inability to calculate and the weaknesses of their proxy mechanisms. In order to get at this distinction, we must also look at the different incentives faced by social and public entrepreneurs and the varying institutional setting they operate in.

Further, it is also worth examining the potential of social entrepreneurs to minimize the social entrepreneur’s epistemic disadvantages compared to commercial entrepreneurs by utilizing analogs to prices and profits and losses. Chamlee-Wright (2004) argues that the differences between the signals that commercial and social entrepreneurs rely on are not as extreme as Boettke and Prychitko (2004) claim. As Chamlee-Wright (2004: 48–49) writes,

… the difference between economic calculation and other guides to action is one of degree, not of kind. Market prices and net monetary returns are not “marching orders.” Profits tell the entrepreneur that she or he is doing something right, but profits do not necessarily signal whether some alternative plan might have generated even more profits. Losses certainly signal the entrepreneur that something is wrong, but just what the entrepreneur is supposed to do in response to these losses is a complex interpretive challenge … As all the possible courses of action and their corresponding outcomes are never laid out before market participants, entrepreneurial decision-making is a process of discovery, not logical deduction … Though monetary calculation is central to market discovery, nonmonetary discovery also takes place as entrepreneurs execute and revise their plans.

This is not to suggest that feedback mechanisms that nonprofits utilize will be more effective guides to action than prices and profits and losses. However, as Chamlee-Wright (ibid.: 50) argues,

With regard to nonprofits, the question seems to be whether they are capable of cultivating enough relevant local knowledge to serve as an effective guide to action. There is no guarantee that any one particular organization will be able to do this, but there is no systematic reason why we would expect sector-wide failure in this regard, either.

Individual nonprofits (and the diverse, broader sector they collectively create) may, indeed, be able to discover, learn, and provide goods and services that further social goals.

More recent scholarship by Austrian economists have focused on the nature of the feedback mechanisms available to nonprofits and the epistemic capacities of social entrepreneurs. For instance, Martin (2010) posits a feedback scale for feedback mechanisms, ranging from tight (which consists of sole proprietorships in markets) to loose (which consists of centralized bureaucracies). In the middle of the spectrum, Martin places private charities. He (ibid.: 232–233) argues that,

These sorts of organizations sport autonomy and free entry without profitability calculations. … They may, however, feature some form of reputational residual claimancy. And since they involve free entry there is scope for experimentation in how to achieve different kinds of ends. Success can be imitated and donor funds must usually be won in competition with other non-profits, thus enabling a genuine social learning process … Their environmental feedback thus lies somewhere between market enterprises and bureaus.

Likewise, Skarbek (2012) explores the epistemic position of entrepreneurs, noting that entrepreneurs in the unhampered market context are epistemically privileged compared to those in non-priced environments. While social entrepreneurs are at an epistemic disadvantage, they may still be able to access knowledge, face the threat of competition, and have the ability to adapt to changing circumstances, for which their success depends.

Further, Lavoie (2001) highlights the scientific community as an analog to markets to show how knowledge is transmitted and improved upon over time in non-market settings. He posits that ideas are analogous to goods and services, personal academic freedom is akin to private property rights, existing theories are analogous to prices, rivalrous controversy and criticism is analogous to rivalrous competition, and reputation is analogous to economic wealth (ibid.). The market for ideas is coordinated, in the search for a progress toward truth, through contestation. Similarly, government intervention distorts the market for ideas just like it distorts the market for goods and services: “The independence of producers from political influence and their free rivalry among on another for profit would be as necessary for economic progress as the independence of a controversy among scientists is for intellectual progress” (ibid.: 18). Viewed in this way, dispersed and inarticulate knowledge is best utilized in decentralized institutions (like the market but also in certain non-market settings, with Lavoie pointing to the scientific community as a relevant example).

Similarly, Storr et al. (2015) argue that the distinction between entrepreneurs across sectors (including commercial, social, political, and ideological) are not differences in kind but are, rather, differences of degree. First, the opportunities that entrepreneurs are alert to across sectors are not dramatically different. While motivations will certainly differ, entrepreneurs of all stripes are trying to engage in plan coordination and, ultimately, social change. For instance, the entrepreneur who opens up a restaurant and the entrepreneur who opens a soup kitchen are both alert to opportunities to providing nourishment. Likewise, the public research universities as well as the for-profit companies who set up and support research laboratories hope that the scientists they support will make innovative breakthroughs.

Second, the feedback mechanisms of the market (those of monetary prices, and profit and loss) are second to none in transmitting knowledge to entrepreneurs, non-priced guides can also convey dispersed and inarticulate knowledge (Lavoie 1985a, 2001; Chamlee-Wright 2010; Martin 2010; Skarbek and Green 2011). Social entrepreneurs can be held accountable for their actions by the close monitoring by donors, leadership boards, and the public, and by maintaining a good reputation (Boettke and Prychitko 2004; Chamlee-Wright 2004; Chamlee-Wright and Myers 2008; Boettke and Coyne 2009) as well as by their ability to attract volunteers and satisfy customers (Storr et al. 2015). For instance, when a church group opens a soup kitchen, they can determine that they are providing a demanded service based on how many people show up, they can determine if they are providing adequate food if people return, and they can determine if donors are pleased with their actions if they continue to fund their efforts.

Third, in the real world, entrepreneurs in the market face a wide array of epistemic challenges that their theoretical counterparts do not, including, but not limited to, that prices are distorted by regulation, subsidies, and other government interventions. These imperfections—coupled with the need to interpret how to respond to the signals of profit and loss (as outlined by Chamlee-Wright 2004 quoted above) as well as the notion that entrepreneurs (across sectors) are motivated by not only prices and profits and losses but also prestige, fame, the desire for social change, and the desire to promote ideological positions—complicates real world economic calculation (Storr et al. 2015). Viewed this way, Storr et al. (ibid.) argue that real world markets may be more imperfect and real-world nonprofits more capable than theory would predict.

It is possible that the literature on economic calculation has led some Austrian economists to overstate the capacity of for-profit firms to engage in rational economic calculation and understate the ability of nonprofit firms to find suitable analogs to prices and profits and losses to guide their behavior. However, as Austrian economists have pointed out in other contexts, in the real-world, prices and profits and losses are not unambiguous indications of success or failure. These signals must be interpreted and reinterpreted over time. Receiving a profit might mean that the firm is engaged in value creation but it could also mean that the firm is benefiting from an artificially created bubble. Similarly, receiving a loss might mean that the firm is wasting resources or it could mean that the firm is building a foundation for long term sustainable revenue growth.

Further, there is no objective difference between an investment and a donation. Losses are often tolerated by investors of for-profit firms as costs needed to build market share or experiment with strategies for monetizing their client networks.Footnote 10 For instance, several firms—such as Amazon, ESPN, Tesla, and Uber—have gone years at a time without earning a profit and yet still continue to have positive market value and consumer satisfaction.Footnote 11 Moreover, because the world changes rapidly, a decision by an investor to stop supporting an enterprise does not say anything definitive about a decision to support that enterprise in a previous period or that other investors should also stop their support. Donors face many of the same issues when deciding to support or continue to support a nonprofit venture. While real world nonprofits are certainly no better off than real world for-profit enterprises regarding their ability to read and rely on signals that guide behavior, it is unclear that real-world nonprofits are considerably worse off than real-world for-profit firms in this regard.

3 The distinction between private and public enterprises

The distinction between calculative, for-profit commercial enterprises and non-calculative, nonprofit social enterprises may overestimate the limits and underestimate the potential of nonprofit social enterprises. Additionally, this distinction alone lacks the explanatory power for why some nonprofits outperform others as well as the conditions under which nonprofits are likely to thrive and the circumstances where they are likely to fail. Therefore, we argue that distinguishing between the private or public characteristics of nonprofits adds theoretical and empirical traction when studying real-world nonprofit social enterprises.

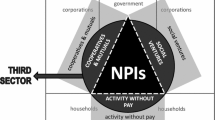

All entrepreneurs and enterprises must be able to assess and identify the problems they hope to address (i.e. the reason and need for their plans), access and understand the information needed to coordinate their plans, acknowledge when errors and changes occur, and must then adapt accordantly. The broader literature in Austrian economics on the advantages of private and decentralized activity highlights how actors in this institutional setting are better able to access information and adapt to changing circumstances. In contrast, the rigid and aggregated nature of public, bureaucratic, and centralized activity constrains the ability of public enterprises to ability to coordinate plans and achieve their goals. As such, we should expect that the more private an enterprise (be it commercial or social in nature), the more likely it is that social learning will occur, that the signals they rely on (whether prices or reputation) will lead entrepreneurs toward plan coordination as well as the discovery and correction of errors. We should expect that the more public an enterprise (be it commercial or social in nature or a government agency), the more likely it is that social learning will be stunted, that the signals will be blunted, and that errors will not be discovered. As such, company X with a large government contract is closer kin to nonprofit Y which relies on government grants, or even to public agency Z, than it is to company A who has no government contracts or nonprofit B who only accepts private, voluntary donations. Similarly, company A and nonprofit B are likely closer kin to each other than to company X, nonprofit Y, and public agency Z. The differences between public and private enterprises are, arguably, salient differences for understanding the potential and performance of specific nonprofits in the real-world.Footnote 12

Chamlee-Wright and Myers’ (2008) discussion of how social learning occurs in non-priced environments highlights the importance of distinguishing between private and public entities in understanding the effectiveness of nonprofit social enterprises. As Chamlee-Wright and Myers (ibid.: 152) describe, social learning is “the phenomenon in which society achieves a level of coordination and cooperation that far exceeds the coordinating capacity of any individual or group of individuals within society.” Social entrepreneurs must be able to learn, correct errors, and discover new and better ways of conducting their operations if they are to provide value to society. “A process of social learning,” they (ibid.: 152) explain, “would require that bad information be weeded out such that social coordination is more likely to emerge than not.” This process involves figuring out some way to access and utilize dispersed knowledge. “Given the appropriate institutional environment,” they (ibid.: 156) write, “individuals can make use of knowledge they do not possess directly, and in turn, render their local, specialized, and often tacit knowledge useful to countless unknown others.”

Utilizing social network theory, Chamlee-Wright and Myers (ibid.) examine how individuals, with combinations of strong and weak ties, can diffuse information (i.e. share information through nodes in their network) and engage in social learning (i.e. provide positive feedback that gets transferred back through the network and incorporated into future action). They (ibid.: 158) suggest that

… to be effective guides to action and generate a system of social learning…signals need to (1) consolidate diverse bits of information into a form that is readily accessible, (2) be adaptable in the face of changing information and allow for low-cost participation in the adjustment process, (3) make it possible to convey local (often tacit) knowledge beyond one’s own close circle of companions, and (4) generate positive feedback loops in which private innovation benefits the wider sphere, which in turn conveys benefit back to the original innovators.

While prices and profits and losses are exemplar signals and feedback mechanisms, meeting all four of these criteria, the signals that can be found in non-priced environments may vary in effectiveness.

The signals that nonprofits can utilize vary widely depending on the scope, scale, and concentration of each individual organization. A social entrepreneur will be alert to opportunities in civil society by interacting in the world around them and identifying areas for improvement. Based on their experiences, location, and cultural context, the entrepreneur is a ‘man on the spot’ who identifies opportunities by interacting with others in society. Once an entrepreneur is alert to an opportunity, determining how to organize, where to buy supplies, and who to employ is also based on their social networks and previous experiences. This process of trial and error builds reputation, status, and trust (or lack of all three) within the community. Chamlee-Wright and Myers (ibid.: 160) argue that reputation, status, and trust are useful signals when utilized “in more competitive environments in which information flows swiftly and at low cost, and norms of upright behavior can be enforced more effectively, then such systems will come closer to approximating the robust cognitive function that prices play and thus potentially serve as a significant source of social learning.”Footnote 13 The ability of donors, volunteers, and customers to monitor a social venture, voice their praise and concern, and encourage adaptation, thus, largely depends on the larger institutional environment.

The appropriate institutional environment that they have in mind is one where nonprofits are allowed to operate without significant government oversight and interference and are able to operate without having to rely on government resources (i.e. an institutional environment where truly private nonprofits are possible). Consider, for instance, how the nature of the signals that nonprofits rely on will differ in more private nonprofits (with less government support and strictures) compared to more public nonprofits (with more government support and strictures). First, in more public nonprofits the relevant bits of information will disproportionately be filtered through one source (i.e. a singular funding source, consolidated donor interests, etc.). The consolidated or aggregated information will be less diverse and less robust than if it came from multiple, even competing sources.

Second, because of the rules and regulations accompanying public grants, more public nonprofits are likely to be less flexible and adaptable than private nonprofits when information and circumstances change. For instance, Grube et al. (2017) examine the entangled relationship between the American National Red Cross and the federal government and how this relationship is at least partly responsible for the recent criticisms of the Red Cross after major disasters, such as Hurricane Sandy. After Hurricane Sandy, the Red Cross, who is tasked with providing shelter and certain services by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), were criticized for delays in services, for spending too much on publicity, and for diverting donations to other activities than the disaster at hand. The growth and bureaucratization of the organization has occurred alongside the connections to federal government.

Third, while all nonprofits are similarly able to make use of signals that convey local (often tacit) knowledge, how that knowledge gets conveyed and interpreted is not the same across all types of nonprofits. The more public nonprofits are likely to privilege guidance they get from the public agencies that support them over any insights gained from others in their communities. Again, take the Red Cross as an example. Since the federal government is a consistent and major funder and regularly utilizes the Red Cross, they are inclined to tailor to their needs over those of individual donors. As such, even when donors express dissatisfaction with the speed and amount of provision the Red Cross provides, the organization has done little to change its procedures and activities (ibid.).

Fourth, the feedback loops that the more public nonprofits are involved in are simply different than the feedback loops that more private nonprofits are involved in. While nonprofits working in communities receive feedback from their partners, recipients, and local donors, that information must get interpreted in light of their goals and those of their major donors. More private nonprofits (that are either smaller in scale or decentralized in their decision making) are more likely to privilege and want to address communal feedback than more public nonprofits that are faced with larger and broader goals and more centralized decision-making processes. Thus, the feedback loops that the more private nonprofits rely on positions them to be responsive to the wishes and desires of community members than their more public counterparts.

Consider, for instance, the performance of public and private enterprises after disasters and their ability to leverage various signals to promote community recovery. As Chamlee-Wright (2010: 15) suggests, “post-disaster environment is an ideal context” for exploring social learning in non-priced environments. As she (ibid.) explains,

First, given the fact that it takes time for official forms of disaster assistance to arrive and normal routines of market life to return, the resources embedded within social networks can prove vital to individual and community-wide recovery. And because it stands in relief to the routines of ordinary life, the social learning that might unfold in this context is more easily identified and analyzed by the outside observer. Second, … some signals essential to community rebound, such as the number of residents within a particular neighborhood who have returned, or the resumption of services by a local church, or the cleanup effort taking place within a neighborhood school are by their very nature non-priced signals.

In order for disaster response and recovery efforts to be successful, the relevant enterprises must be able to identify opportunities, access necessary knowledge, and adapt to changing conditions in the post-disaster context (Sobel and Leeson 2007; Storr and Haeffele-Balch 2012; Storr et al. 2015).Footnote 14 Historically, associations have played a major role in disaster recovery, such as in the aftermath of the Chicago Fire of 1871 (Skarbek 2014). Conversely, public enterprises have often faced severe challenges overcoming the knowledge problems that are inherent in post-disaster response and recovery. For instance, the FEMA was late declaring Hurricane Katrina a disaster, failed to identify the areas that lacked necessary supplies (such as water) in a timely manner, often resulting in duplicating the efforts of for-profit businesses and nonprofit organizations, and, despite its failures, was rewarded with a larger budget and more responsibility rather than less (Sobel and Leeson 2007).

Similarly, the more public nonprofits (e.g. the Red Cross) tend to perform worse than more private nonprofits (e.g. churches and neighborhood associations) performed quite effectively after Hurricane Katrina. For instance, a Vietnamese community in New Orleans, Louisiana, was able to rally around their pastor, their church community, and the unique talents of their community members to overcome challenges of rebuilding (Chamlee-Wright 2010; Storr et al. 2015). They fought efforts to halt rebuilding in their neighborhood and to build a landfill just outside their neighborhood and came together to process forms for assistance and provide translation services (ibid.). Additionally, the neighborhood association in the Broadmoor area of New Orleans was able to identify the needs of their community, use their diverse experiences and connections to funnel resources to their cause, and adapt to changing circumstances (Storr and Haeffele-Balch 2012). In the case of Broadmoor, which the city planning committee had at first proposed should be turned into green space, residents were able to locate dispersed residents, determine who was willing to return, and prove the vitality of their neighborhood through collective return. Community-based action was more adaptable and ultimately more successful than the efforts of more public nonprofits and public enterprises (Chamlee-Wright and Storr 2009; Chamlee-Wright 2010; Storr et al. 2015).

More private nonprofits are established by voluntary means, face competition from existing and potential future rivals, adapt to changing circumstances, and are, thus, more likely to coordinate their plans and achieve their goals. Mises appears to have held a similar view, highlighting the value of nonprofits, especially those that are more-private in nature. In a letter to Dick Cornuelle discussing his book, Reclaiming the American Dream, Mises (1965) remarked,

In this country people distinguish nowadays between the public sector and the private sector. You are dealing in your book with what you call the independent sector. I fully agree with all you say in the appreciation of the activities to which you assign this term. But are these activities independent? Are they not rather possible only within the frame of the private sector? Does not the sector called the private have a fair claim to the appellation “independent”? You are pointing out that what is called the public sector through its aggressive expansion continually restricts the field in which independent actions of the citizens can operate … But does not this prove that the actions of the independent sector are essentially a manifestation of the same spirit that animates also the actors in the private sector? What matters is that in the private as well as in the sector you call independent there is only voluntary spontaneous action of individuals and groups of individuals, while the characteristic feature of the public sector is coercion and compulsion.

Highlighting the differences between the private and public sectors, as outlined above, can aid in our study of a variety of scenarios dealing with governance and societal progress in both times of crisis and of everyday life. The institutional characteristics of the private sector (such as private property, competition, and adaptation) allow for experimentation which can lead to plan coordination and social learning (through successful innovation as well as error identification and correction). Indeed, in the post-disaster context, decentralized organizations led by entrepreneurs—such as neighborhood associations, churches, stores, and community-based health clinics—successfully provided goods and services that their communities demanded, reestablished their social networks to better facilitate communication and coordination, and were drivers of recovery (Chamlee-Wright 2010; Storr et al. 2015). The institutional characteristics of the public sector, on the other hand, encourage rigidity and the preservation of the status quo (Storr et al. 2015). Unsurprisingly, agencies like FEMA are often criticized for being too slow and too rigid (and too corrupt) following every major disaster (see Sobel and Leeson 2007; Leeson and Sobel 2008; NPR 2014). Further, the study of nonprofits that emphasizes the differences between more private nonprofits and more public nonprofits allows for a deeper study of the distortions that are likely to result from government involvement in the nonprofit sector and the disadvantages of public-private partnerships.Footnote 15

A brief look at the developments of Habitat for Humanity International (Habitat) over the past few decades helps highlight the potential of nonprofits to coordinate their plans and achieve social goals as well as the pitfalls associated with government involvement in the nonprofit sector. Habitat is an international nonprofit organization that provides the opportunity of owning affordable, modest homes to low-income individuals living in inadequate housing.Footnote 16 Founded by Millard and Linda Fuller in 1976, the organization aimed to foster community-development and provide affordable housing through “partnership building” (Youngs 2007; Baggett 2000; Fuller 1994). Habitat now has over 1500 affiliates in cities and counties across the United States, as well as operations in countries throughout the world.

Habitat facilitates homeownership for those who are willing to work and are able to pay for their home. Individuals applying for homes must meet a series of requirements before receiving a house from Habitat: they must (1) make between 25 to 50% of the area’s median income; (2) meet credit score requirements (also relative to the general area); (3) take classes on homeownership, home repair, and personal finances; (4) complete ‘sweat equity’ hours by working on other homes or at Habitat offices; and (5) make monthly payments on their at-cost, no-interest mortgages (Husock 1995; Baggett 2000). The organization’s goal is to support, train, and enable homeowners to better their lives. This process is a way to ensure that individuals and families that seek housing are ready for the responsibility, burdens, and rewards of homeownership; this process helps to protect the organization against a consistent misallocation of resources and also provides checkpoints to reassess investments and make corrections when necessary (Haeffele and Storr 2019). While the centralized headquarters track national and international progress, prospective residents are screened and the houses are built by local affiliates (Husock 1995; Baggett 2000). Additionally, local affiliates often cooperate (and compete) with other organizations in the area, giving them access to a wider network to share information and learn from each other.

Haeffele and Storr (2019) examined the effectiveness of the Habitat affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama. By studying the organization over the course of 2009–2010, they found that the organization was able to effectively alter the mix of affordable housing and foster homeownership as well as financial stability because of the characteristics and procedures they have established, including an extensive application process, allowing applicants to work on their credit score and finances without having to start the process over, requiring participants to attend workshops on maintaining their home and their finances, requiring participants to work for their home (sweat equity hours), providing a flexible timeline and an individualized building process, and allowing for flexible payments when homeowners encounter challenging times.Footnote 17 Further, through the process of qualifying for and acquiring their home, homeowners built lasting relationships with volunteers, Habitat employees, and neighbors that lead to a sense of community and future volunteerism (ibid.). While each affiliate follows a general process to screen and monitor applicants, they can also adapt their processes to the needs and challenges of their community. Thus, Habitat has found ways to successfully provide affordable housing to the poor by relying on a decentralized structure (ibid.).

However, in the past ten years, Habitat has become more public in nature by actively lobbying for government intervention into the housing market and pursuing public sector grants. In 2005, the Fullers were terminated by the Habitat board of directors and a new chief executive officer, Jonathon Reckford, was brought on board shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Louisiana. While the Fullers resisted pursuing government funding, Reckford began to build partnerships with both the US government and other governments throughout the world. For instance, a vice president for governmental affairs was hired and an office was set up in Washington, DC in 2006, and grant money and stories of partnerships with governments started becoming prominent features in Habitat’s annual reports (HFHI 2005, 2008, 2010). Expenditures previously dubbed “education” began to be referred to as “advocacy,” likely encompassing lobbying efforts in addition to public outreach campaigns.

Furthermore, after the financial crisis of 2008, local affiliates (including the one in Birmingham, Alabama) began receiving federal grants to purchase, renovate, and sell foreclosed homes (HFHGB 2010). The Birmingham affiliate initially saw this as an opportunity to increase its presence and impact in the community without siphoning money from traditional operations. However, their annual reports have stopped distinguishing between their traditional program and the renovation program, potentially signaling that these grants have, indeed, retarded their ability to sustain their traditional programs (HFHGB 2012, 2013).

While the extent to which Habitat has become more public and whether this has reduced its effectiveness is still an open question, it is clear that the organization has begun to focus more on government partnerships. Such intermingling with government may also result in weaker feedback mechanisms and promote the status quo rather than a process of social learning and progress. Further research examining Habitat, the Red Cross, and other nonprofits with this framework may bring additional insights into the difference in how nonprofits are structured and their effectiveness in bring about social goals.

4 Conclusion

There is a large literature on the role of nonprofit enterprises in robust civil society (see, for instance, de Tocqueville [1835] 2012; Cornuelle [1965] 2011; Weisbrod 1988; Lohmann 1992; Salamon 2003; Acs 2013). This literature advocates for nonprofits to be either competition for government-provided goods and services or complements and extensions of government action, but largely leaves the questions of how nonprofit social enterprises go about identifying opportunities, allocating resources, and adapting to changing circumstances unaddressed. Boettke and Prychitko (2004) identify this gap in the literature and argue that such an analysis should follow an Austrian approach. This paper furthers the exploration of nonprofits within Austrian economics and advances a way to study nonprofits that also uses a private vs. public distinction, in addition to the market vs. non-market distinction.

Since civil society exhibits both private and public characteristics, it is the movement toward private activity (rather than public activity) that enables nonprofit social enterprises to identify opportunities, access necessary knowledge, and engage in social learning (or not). This is highlighted by the example of Habitat for Humanity International and its affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama, whose decentralized structure enabled local affiliates to adapt to the needs of their community (characterized as private in nature) and whose growing involvement with government has reduced accountability and transparency (a movement toward being more public in nature).

Furthermore, future research that utilizes this distinction can 1) examine the coordinating characteristics of nonprofits, 2) examine how government intervention distorts the missions, actions, and outcomes of nonprofits, and 3) identify enterprises that normally are categorized as market or non-market that are actually better suited as categorized as private or public (for instance, how businesses that heavily rely subsidies may be more public than private in nature).

Notes

For a discussion on the definition of the nonprofit sector and how it, at least until the last few decades, has been understudied, see Salamon and Anheier (1992).

Of course, nonprofits can be unsuccessful as well. They often lose donors and volunteers when people do not approve of their practices or the goods and services they provide, they end up not helping the people they hope to help, and they often face pressure to change their ways, shrink their portfolios, or close up shop.

While Acs (2013) views this as a robust capitalist system, he nonetheless promotes coexistence, rather than competition, with the state.

This approach is different than studying traditional organizations that fit within the private and public distinction (notably, markets and governments). It is about using the categories of private and public for studying how effective and flexible an organization is (whether within markets, civil society, or even possibly government).

Cornuelle inspired and encouraged others to pursue the possibilities of nonprofits. His contribution is explored in volume 10 of Conversations in Philanthropy, http://www.conversationsonphilanthropy.org/journal/volume-x/.

See Aligica (2015) for a discussion on the continued gap in the literature.

The Austrian contribution to economic calculation began when Mises critiqued the notion that socialism can match or outperform the material progress and social benefits achieved through markets. Mises ([1920] 1963) argued that markets are able to coordinate plans and allocate resources efficiently through rational economic calculation because of the existence of private property rights (which enable exchange in the means of production), monetary prices over the means of production (which signal relative scarcity when determining between various alternatives), and the feedback mechanism of profit and loss (which signals success, encourages error correction, and promotes innovation). Socialism eliminates private property and, thus, undermines the system of economic calculation. As the socialist calculation debate continued, Mises and Hayek further refined their arguments to highlight the coordinating tendencies of markets—such as the role of entrepreneurs in correcting errors in the market through arbitrage and innovation (Mises [1949] 2007; Kirzner 1973), the role of prices in disseminating dispersed and inarticulate knowledge (Hayek 1948; Lavoie 1985a, 1985b, 2001), and the role of rivalry in incentivizing productive behavior while constraining unproductive activities (Hayek 1948; Lavoie 1985a, 1985b). The emphasis on knowledge highlights the way in which prices and profit and loss coordinate the plans of individuals within the market and leads to the distinction between market and non-market activity.

Ironically, the social entrepreneur wants to do social good but cannot ever be sure that they are actually doing good. The commercial entrepreneur, on the other hand, cares primarily about doing good for themselves but must necessarily do good for others if they hope to improve their own lot.

Thus, this approach provides an important to critique to the application neoclassical economics to nonprofit enterprises and calls for a robust study of social enterprises that examines knowledge problems and comparative institutional analysis (see Boettke and Prychitko 2004; Aligica 2015). This paper takes that call to action seriously and attempts to further develop an Austrian approach to nonprofit enterprises.

Of course, it is possible and even likely that this ambiguity only exists in the short run and that in the long run any errors will be revealed (i.e. consistent losses will eventually cause investors to reconsider supporting the endeavor).

Admittedly, the entrepreneurs and enterprises we observe and examine in the real world often contain elements of both private and public activity; these characteristics are not mutually exclusive but rather intermixed in a modern society. As such, a large firm that takes government subsidies and supports regulation that restricts competition exhibits characteristics of a public organization although it ostensibly rests within the market order. A particular publicly-funded university that fosters an environment of academic freedom where scholars debate ideas and critique each other’s research in the search for truth exhibits characteristics of a private organization although it supposedly rests within the government system.

Furthermore, “If the conditions are right, informal systems of reputation and status can feed into community-level norms of trust, reciprocity, and rules of just conduct. Thus, a sound reputation rewards not only the person who possesses it, but also spills benefit over to the community at large by reinforcing social rules that foster widespread cooperation, coordination, and mutual support in both market and non-market contexts” (Chamlee-Wright and Myers 2008: 161).

First, Sobel and Leeson (2007: 520) posit that effective disaster relief efforts must succeed in three broad areas: “The first is the recognition stage: Has disaster occurred, how severe is it, and is relief needed? The second is the needs assessment and allocation stage: What relief supplies are needed, who has them readily available, and what areas and individuals need them the most? The third stage is the feedback and evaluation stage: Are our disaster-relief activities working, and what, if anything, needs modification?” And, second, Storr and Haeffele-Balch (2012: 320) build off of their approach in order to determine criteria for effective recovery efforts, which “must determine (a) which residents are most likely to return and which neighborhoods are most likely to rebound, (b) how best to allocate resources, and (c) when it has made mistakes and how to correct them.”

As, Boettke and Prychitko (2004: 25–26) argue, social entrepreneurs “would have a greater incentive than government officials to assess effectiveness, because … they cannot rely upon the power to tax. Instead, they must depend upon the voluntary contributions of their donors. This, of course, is problematic in our society, where many nonprofits often bypass the responsibility of persuasion and voluntary exchange and instead seek support from the state (not unlike many private business enterprises). In this regard, to accept Salamon’s advocacy of third-party government, which in effect seeks to legitimate nonprofit firms as arms of state action, would further weaken the effectiveness of nonprofit organizations by encouraging them to engage more in political rent-seeking than in marketplace persuasion.”

For more information, see http://www.habitat.org/how/default.aspx.

This time period was arguably the peak of the Birmingham Habitat affiliates success, having expanded its jurisdiction, and was recognized by Habitat for their capacity and effectiveness.

References

Acs, Z. (2013). Why philanthropy matters: How the wealthy give and what it means for economic well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Aligica, P. D. (2015). Addressing limits to mainstream economic analysis of voluntary and nonprofit organizations: The Austrian alternative. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(5), 1026–1040.

Anheier, H., & Ben-Ner, A. (Eds.). (2003). The study of the nonprofits Enterprise: Theories and approaches. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Baggett, J. (2000). Habitat for humanity: Building private homes, building public religion. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Boettke, P. J., & Coyne, C. J. (2009). Context matters: Institutions and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 135–209.

Boettke, Peter J. and David Prychitko. (2004). Is an independent nonprofit sector prone to failure? Toward an Austrian School interpretation of nonprofit and voluntary action. Conversations on Philosophy, Volume 1: Conceptual Foundations: 1–40.

Brinkerhoof, J. M., & Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2002). Government-nonprofit relations in comparative perspective: Evolution, themes and new directions. Public Administration and Development, 22(1), 3–18.

Carmen, J. G., & Fredericks, K. A. (2010). Evaluation capacity and nonprofit organizations: Is the glass half-empty or half-full? American Journal of Evaluation, 31(1), 84–104.

Chamlee-Wright, Emily. (2004). Comment. Conversations on Philosophy, Volume 1: Conceptual Foundations: 45–51.

Chamlee-Wright, E. (2010). The cultural and political economy of recovery: Social learning in a post-disaster environment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Chamlee-Wright, E., & Myers, J. (2008). Discovery and social learning in non-priced environments: An Austrian view of social network theory. The Review of Austrian Economics, 21(2/3), 151–166.

Chamlee-Wright, E., & Storr, V. H. (2009). The role of social entrepreneurship in post-Katrina Community recovery. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 2(1/2), 149–164.

Cornuelle, Richard. ([1965] 2011). Reclaiming the American dream: The role of private individuals and voluntary associations. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Cornuelle, R. (1983). Healing America: What can be done about the continuing economic crisis. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

de Tocqueville, Alexis. ([1835] 2012). Democracy in America.. Edited by Eduardo Nolla, translated by James T. Schliefer. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, Inc.

Fox Business. (2015). Big companies without profits–Amazon, Twitter, Uber and Other big Names that Don’t Make Money. Fox Business, October 30. https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/big-companies-without-profits-amazon-twitter-uber-and-other-big-names-that-dont-make-money. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Fuller, M. (1994). The theology of the hammer. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing.

Gazley, B. (2010). Linking collaborative capacity to performance measurement in government—Nonprofit partnerships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(4), 653–673.

Gazley, B., & Brudney, J. L. (2007). The purpose (and perils) of government-nonprofit partnership. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(3), 389–415.

Grube, L. E., Haeffele-Balch, S., & Davies, E. G. (2017). The organizational evolution of the American National red Cross: An Austrian and Bloomington approach to organizational growth and expansion. Advances in Austrian Economics: The Austrian and Bloomington Schools of Political Economy, 22, 89–105.

Habitat for Humanity International. (2005). Annual Report: FY2005.

Habitat for Humanity International. (2008). Annual Report: FY2008.

Habitat for Humanity International. (2010). Annual Report: FY2010.

Habitat for Humanity of Greater Birmingham. (2010). Annual Report: Year End June 2010.

Habitat for Humanity of Greater Birmingham. (2012). Annual Report: Year End June 2012.

Habitat for Humanity of Greater Birmingham. (2013). Annual Report: Year End June 2013.

Haeffele, S., & Storr, V. H. (2019). Hierarchical management structures and housing the poor: An analysis of habitat for humanity in Birmingham, Alabama. Journal of Private Enterprise, 34(1), 15–37.

Hayek, F. A. (1948). Individuals and economic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hendricks, Drew. (2014). 5 successful companies that Didn’t make a Dollar for 5 years. Inc., July 7. https://www.inc.com/drew-hendricks/5-successful-companies-that-didn-8217-t-make-a-dollar-for-5-years.html. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Husock, H. (1995). It’s time to take habitat for humanity seriously. City Journal, 5(3).

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lavoie, D. C. (1985a). Rivalry and central planning: The socialist calculation debate reconsidered. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lavoie, D. C. (1985b). National Economic Planning: What is left? Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Lavoie, D. C. (2001). The market as a procedure for discovery and conveyance of inarticulate knowledge. Comparative Economic Studies, 28, 1–19.

Leeson, P. T., & Sobel, R. S. (2008). Weathering corruption. Journal of Law and Economics, 51(4), 667–681.

Lohmann, R. A. (1992). The commons: New perspectives on nonprofit organizations and voluntary action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacIndoe, H. (2013). Reinforcing the safety net: Explaining the propensity for and intensity of nonprofit-local government collaboration. State and Local Government Review, 45(4), 283–295.

Martin, A. (2010). Emergent politics and the power of ideas. Studies in Emergent Order, 3, 212–245.

Mises, Ludwig. ([1920] 1963). Economic calculation in the socialist commonwealth. In Collectivist economic planning, edited by F. Hayek. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul LTD.

Mises, Ludwig. ([1949] 2007). Human action: A treatise on economics, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Mises, L. (1965). Correspondence between Mises and Cornuelle. Ludwig von Mises Archives at Grove City College, (November 1).

NPR. (2014). Red Cross 'Diverted Assets' During Storms' Aftermath To Focus On Image. NPR Special Report: The American Red Cross, October 29. http://www.npr.org/2014/10/29/359365276/on-superstorm-sandy-anniversary-red-cross-under-scrutiny. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Richmond, B. J., Mook, L., & Jack, Q. (2003). Social accounting for nonprofits: Two models. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 13(4), 308–324.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (Ed.). (1986). The economics of nonprofit institutions: Studies in structure and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salamon, L. M. (1981). Rethinking public management: Third-party government and the changing forms of government action. Public Policy, 29(3), 255–275.

Salamon, L. M. (1987). Of market failure, voluntary failure, and third-party government: Toward a theory of government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Journal of Voluntary Action Research, 16(1–2), 29–49.

Salamon, L. M. (1995). Partners in Public Service: Government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Salamon, L. M. (Ed.). (2002). The state of nonprofit America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Salamon, L. M. (2003). The resilient sector: The state of nonprofit America. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector. I: The question of definitions. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 3(2), 125–151.

Skarbek, E. C. (2012). Experts and entrepreneurs. Advances in Austrian Economics: Experts and Epistemic Monopolies, 17, 99–110.

Skarbek, E. C. (2014). The Chicago fire of 1871: A bottom-up approach to disaster relief. Public Choice, 160(1–2), 155–180.

Skarbek, E. C., & Green, P. R. (2011). Associations and order in the cultural and political economy of recovery. Studies in Emergent Order, 4, 69–77.

Skelcher, C. (2007). Public-private partnerships and hybridity. In E. Ferlie, E. Lynn Jr., & C. Pollitt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public management (pp. 347–370). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, S. R., & Gronbjerg, K. A. (2006). Scope and theory of government-nonprofit relations. In W. W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (pp. 221–242). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sobel, R. S., & Leeson, P. T. (2007). The use of knowledge in natural-disaster relief management. Independent Review-Oakland, 11(4), 519–532.

Stater, K. J. (2010). How permeable is the nonprofit sector? Linking resources, demand, and government provision to the distribution of organizations across nonprofit Mission-based fields. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(4), 674–695.

Storr, V. H., & Haeffele-Balch, S. (2012). Post-disaster community recovery in heterogeneous, loosely-connected communities. Review of Social Economy, 70(3), 295–314.

Storr, V. H., Haeffele-Balch, S., & Grube, L. E. (2015). Community revival in the wake of disaster: Lessons in local entrepreneurship. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Watson Bishop, S. (2007). Linking nonprofit capacity to effectiveness in the new public management era: The case of community action agencies. State and Local Government Review, 39(3), 144–152.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1988). The nonprofit economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wing, K. T. (2004). Assessing the effectiveness of capacity-building initiatives: Seven issues for the field. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(1), 153–160.

Young, D. R. (2000). Alternative models of government-nonprofit sector relations: Theoretical and international perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149–172.

Youngs, B. B. (2007). The house that love built: The story of Linda & Millard Fuller, founders of habitat for humanity and the Fuller Center for Housing. Newburyport, MA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haeffele, S., Storr, V.H. Understanding nonprofit social enterprises: Lessons from Austrian economics. Rev Austrian Econ 32, 229–249 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-019-00449-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-019-00449-w