Abstract

In a previous exploratory analysis of the 2009 EU-SILC survey and the Eurostat statistics database, the authors tried to reveal to what extent self-perceived poverty in Europe is associated with specific household socioeconomic characteristics and particular aspects of household/community social capital endowment, by means of a multiple correspondence analysis. Such an analysis has appeared to be a useful tool to disclose the primary risk factors of family poverty status and, in particular, it showed that self-perceived poverty (measured by the proxy variable “ability to make ends meet”) is strongly associated not only with household socioeconomic characteristics, but also with the indicators commonly recognized as elementary proxies of household/community social capital endowment. The aim of the present paper is to capture the effect of social capital on household subjective poverty. More precisely, a generalized ordered logit model is estimated, in order to highlight to what extent: (a) self-perception of poverty in Europe is affected by the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics and by household/community social capital endowment; (b) probabilities corresponding to response categories vary according to different levels of predictors; (c) differences among European countries in terms of self-perception of poverty may be related to different levels of social capital endowment. The results are very encouraging and confirm that social capital could be used by local and central governments as a further key function, in addition to the traditional socioeconomic ones for planning poverty reduction policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to the most widely accepted definition suggested by the World Bank Social Capital Initiative Program research group, social capital includes the institutions, the relationships, the attitudes and values that govern interactions among people and contribute to economic and social development (Grootaert and van Bastelaer 2002). This definition synthesizes the different points of view expressed by Putnam et al. (1993), Coleman (1990), Olson (1982) and North (1990) and implies that living in a society characterized by model and cooperative behavior, and where trust replaces suspicion and fear, can have a systematic positive effect on individuals’ perception of poverty as their socioeconomic vulnerability is reduced as well as the resources they need to deal with risk and to avert major losses (Helliwell 2001).

There is a growing empirical evidence that social capital contributes significantly to development outcomes (that is growth, equity and poverty alleviation). In particular, for researchers interested in economic development, social capital has great intuitive appeal as a resource available to poor people who are often described as deficient along other vectors such as, for example, human, physical, and financial capital (Grootaert and van Bastelaer 2001; Woolcock 2002). Since the seminal work of Putnam et al. (1993) on the role of social capital in explaining Italian regions economic success, interest in the relationships between social capital and poverty has been growing rapidly (Collier 1998; Grootaert 1999; Grootaert et al. 1999; Narayan 1999; Narayan and Pritchett 1999; Rose 1999; Maluccio et al. 2000; Woolcock and Narayan 2000; Tiepoh and Reimer 2004; Levesque 2005; Yusuf 2008; Roslan et al. 2010; Hassan and Birungi 2011; Christoforou and Davis 2014).

The mechanism through which social capital is said to reduce poverty can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

at the micro level social ties and interpersonal trust facilitate the flow of technical information and knowledge that help to reduce economic transactions costs (Barr 2000) and ameliorate conventional resource constraint such as labour and credit market access (Coleman et al. 1966; Granovetter 1995; Fernandez et al. 2000), thus reducing the vulnerability of households to poverty (Knack 1999);

-

2.

at the macro level social engagement and civic responsibility can also strengthen democratic governance (Almond and Verba 1963), a mix of norms and sanctions can control defection and dishonesty (Bebbington and Perreault 1999) and improve the efficiency and honesty of public administration (Putnam et al. 1993; Fukuyama 1995) as well as the quality of economic policies (Easterly and Levine 1997).

Moreover, social capital can be viewed as a form of asset embedded in social structures and relationships with a productive capacity that can be extended beyond generating economic returns to providing (but not always) useful benefits for attaining many other different goals (Knack and Keefer 1997); these goals may be, for example, human capital accumulation (Galor and Zeira 1993; Coleman 1988), social efficient outcomes such as social cohesion (Reimer 2002; Green et al. 2003) and social capability (Abramovitz 1986; Abramovitz and David 1996).

The growing importance of social capital as a major determinant of economic well-being at micro and macro level has increased its implications in social policy as a tool to achieve better outcomes of traditional public policies aimed at poverty reduction. Indeed, since many years, both researchers and policy-makers have shown an increasing interest towards the subjective and multidimensional aspects of poverty (Goedhart et al. 1977; Van Praag et al. 1980; Sen 1982; Massoumi 1986; Case and Deaton 2002; Deutsch and Silber 2005; Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2006), arguing that poverty is not an objective status based exclusively on the level of income necessary to satisfy household needs but also depends on people’s perceptions and feelings, on the resources that are essential for full participation/inclusion in society and on environmental aspects of people’s lives (Van Praag et al. 2005; Tomlinson et al. 2007). Several empirical studies have shown how and to what extent in Europe self-perceived povertyFootnote 1 is associated with household size and type, individual and household socioeconomic characteristics (i.e. gender, age, employment status, education, tenure status, the area of residence), available household resources (Van Praag and Van der Sar 1988; Ravaillon and Lokshin 2002; Hayo and Seifert 2003; Stanovnik and Verbic 2004; Castilla 2010; Cracolici et al. 2011; Cracolici et al. 2012; Buttler 2013).

Limited attention has been, instead, devoted to the analysis of the relationships with household and community social capital endowment.

In a previous study (Guagnano et al. 2013), using Multiple Correspondence Analysis, the authors identified some significant patterns of relationships among a set of active variables describing, respectively, the respondent/household socio-economic characteristics and different forms of household/community social capital endowment. In particular, the analysis showed a relevant association in European countries between self-perceived poverty and the majority of the household/community social capital endowment proxy variables.

The subsequent objective, the aim of this paper, is to qualify this association and to assess how and to what extent the overall household/community social capital endowment and its most relevant components contribute to improve household perceived poverty. Such evidence has important policy implications as would help central and local governments to define those economic and social goals which should receive more attention by poverty reduction policies. In order to pursue this aim, a generalized ordered logit model (Mc Cullogh and Nelder 1989; Peterson and Harrel 1990; Fu 1998; Williams 2006) is carried out on data from the 2009 EU-SILC survey and Eurostat statistics database.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the data and the methodology used, Sect. 3 presents the results and Sect. 4 provides some concluding remarks and future research lines.

2 Data and Methodology

2.1 Data

Data used in this study come from the 2009 cross-sectional EU-SILC surveyFootnote 2 and Eurostat statistics database. As a matter of fact, EU-SILC is the reference source for comparative studies on income distribution, poverty and social exclusion at European level (Eurostat 2009, 2010; Santini and De Pascale 2012a, b); its purpose is to monitor household economic and social conditions for aware planning of economic and social policies (Clemenceau et al. 2006). The 2009 survey provides, for all the 27 EU member states, a wide range of variables which will be used in the present study.

2.1.1 The Dependent Variable

The EU-SILC survey provides information on household subjective poverty consistent with the aim of this study. In particular, the variable Ability to make ends meet, corresponding to the question A household may have different sources of income and more than one household member may contribute to it. Thinking of your household’s total income, is your household able to make ends meet, namely, to pay for its usual necessary expenses?, can be employed as a measure of the perceived income adequacy (Whelan and Maître 2009; Goedemé and Rottiers 2011; Cracolici et al. 2012); its levels are the following six ordered categories: with great difficulty; with difficulty; with some difficulty; fairly easily; easily; very easily.

2.1.2 Explanatory Variables

The possible determinants of subjective poverty considered in the analysis are:

-

(a)

The respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics suggested by empirical literature already mentioned in Sect. 1 (Van Praag and Van der Sar 1988; Ravaillon and Lokshin 2002; Hayo and Seifert 2003; Stanovnik and Verbic 2004; Castilla 2010; Cracolici et al. 2011, 2012; Buttler 2013). They are listed in Table 2 of the Appendix and are: age, gender, marital status, education, employment status, low work intensity status, branch of activity, risk of poverty and social exclusion, general health, house/flat size, tenure status, dwelling type, reasons for changing dwelling, household type, equivalized disposable income, poverty indicator, material deprivation, financial burden of housing cost, debts, work intensity status, family/children allowances, social exclusion, housing allowances, indicators of cash received, alimonies received and income received by people aged under 16.Footnote 3

The respondent’s socioeconomic characteristics are included to take into account the features of the person who answers, on behalf of the whole family, to the household questionnaire and, in particular, to the question on ability to make ends meet.

-

(b)

The household/community social capital endowment.Footnote 4 The proxy variables, listed in Table 3 of the Appendix, have been selected so as to be consistent with the most widely accepted definition of social capital mentioned in Sect. 1 (see for discussion Santini and De Pascale 2012a, b). They are indicators of the level of:

-

1.

social behavior (SB);

-

2.

social relationships (SR);

-

3.

those specific territorial and environmental characteristics (TC) which are significant determinants of social capital formation.

-

1.

In particular:

-

1.

Social behaviour includes all indicators that directly and indirectly measure the degree of moral behavior. Social capital involves networks and relationships but only those characterized by trust; however, the mechanism linking interpersonal trust with economic and social outcomes refers implicitly to honesty and civic morality (Fukuyama 1995; Knack and Keefer 1997; Putnam et al. 1993). As emphasized by Letki (2006), civic morality is an ethical habit […]. It refers to the sense of civic responsibility for the common good, […] it is rooted in community membership and implies accepting duties as given by society and owed to all of its members or society in general. […] It also deters citizens from engaging in crime, corruption and illegal activities of any other sort, therefore diminishing the amount of resources that need to be employed to provide order and rule of law.

Perceived crime, violence and vandalism as well as rate of crime and degree of environmental deprivation (questions on “litter lying around” and “damaged public amenities”) are proxy indicators of the level of civic morality and honest and responsible behavior.

-

2.

Social relationships includes all indicators that directly and indirectly measure the degree of informal socializing which refers to the actual or potential resources linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition [….] directly usable in the short or long term (Bourdieu 1986), thus reducing people social exclusion which represents a significant nonmaterial dimension of poverty (Sen 2000).

As far as social relationships indicators are concerned, a distinction between real and virtual relationships has been made. Real relationships are those based on face-to-face formal or informal socializing; they can be transformed in durable networks that provide access to resources, information or assistance and from them one can derive market and non-market benefits (i.e. better social status, better educational and professional achievement). Virtual relationships provide the same benefits of real relationships but are based on networks of heterogeneous contacts generated via-computer over the internet.

The following variables from EU-SILC seem relevant to virtual and real relationships: the questions Do you have a computer? and Do you have an internet connection? detect the availability of the technological instrument which facilitates the creation of virtual networks, while the variable Do you have a phone? (including mobile phone) detects the availability of a device which helps to keep alive both real and virtual relationships. The variable Do you have a colour tv? measures a negative feature of social relationships. Some authors (as, for example, Olken 2006) have empirically verified that more time spent watching television is associated with substantially lower levels of participation in social activities and with lower self-reported measures of trust. Even Putnam, in a series of books and articles, famously argued that social capital in the United States has been declining over the past 40 years—and that the rise of television is a major factor behind this decline (Putnam 1995, 2000).

As regards real relationships, EU-SILC provides the following proxy variables: Number of hours of child care by grandparents, others household members (outside parents), other relatives, friends or neighbors, and Are there “family workers” Footnote 5 in your family business? They capture the existence of support relationships which an individual can use to cope with child care, management of family firms, financial needs. Furthermore, the set of questions about leisure and social activities of household members helps to measure the degree of informal socializing.

-

3.

Territorial and environmental context, includes those context characteristics which are significant determinants of social capital formation (Loopmans 2001; Glaeser et al. 2002). A high rate of overcrowding and shortage of space in dwelling should be a symptom of poor living conditions which could have a negative effect on the quality of family relationships. This aspect is further emphasized by the introduction of additional variables on housing and environmental conditions such as features of the house or the dwelling and of its surroundings, exposure to air pollution, greenhouse gas emission (in CO2 equivalent).

Bearing in mind that our aim is to measure the effect on subjective poverty of social capital endowment, both on the whole and with regard to each of its components, we combined the proxy variables within each of the three categories into complex indexes: a simple arithmetic mean has been used hypothesizing that they are perfectly and mutually replaceable as they measure different aspects of the same phenomenon.

Furthermore, an overall social capital index has been obtained pulling together the three complex indexes through a simple geometric mean, as it implies a lower interchangeability of categories.

2.1.3 Methodology

Given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, an ordered response model should be used. In our analysis the proportional odds assumption is violatedFootnote 6; therefore the most general specification of such a model has been used: the partial proportional odds or generalized ordered logit model (Mc Cullogh and Nelder 1989; Peterson and Harrel 1990; Fu 1998; Williams 2006), that is an ordered logit model which allows estimates (not necessarily all) to vary across categories.

Formally, for an ordinal dependent variable Y with J categories, the generalized ordered logit model can be written as:

with

and where i refers to the household, X i is the vector of predictors for the i-th household and β j is the vector of parameters to be estimated.Footnote 7

Furthermore, since some researchers prefer to continue using the ordinal logit model even when the assumption is violated, especially because the generalized model can produce negative predicted probabilities (see Mc Cullogh and Nelder 1989, p. 155), for comparative purposes and for better evaluating the implication of the violation, we also estimated a standard ordered logit model.

In order to assess how and to what extent social capital contributes to improve self-perception of poverty, three different models have been estimated:

-

the first model (M1) includes as explanatory variables only the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics and represents the benchmark model;

-

the second model (M2) includes as explanatory variables both the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics and the overall social capital index;

-

finally the third model (M3), includes as explanatory variables, in addition to the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics, the three complex indexes defined in Sect. 2.1.2, to take into account the three different aspects of social capital.

Therefore, model M1 only evaluates the effect on perceived poverty of the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics; model M2 evaluates the effect of both the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics and social capital endowment on the whole; finally, model M3 evaluates the effect of both the respondent/household socioeconomic characteristics and the three components of social capital.

3 Results

Estimates obtained for the more general specification (M3), considering the category ‘very easily’ as the base category, are listed in the Appendix (Table 4).

All the estimated regression parameters are significant for at least one equationFootnote 8; this is generally true also for models M1 and M2.

The global performance of the model can be judged satisfactory, especially if we consider that the response categories are six and the percentage of very easily responses is very low (4.7 %), making it more difficult to correctly predict this category.Footnote 9

Percentages of correctly predicted responses, obtained for each model, are listed in Table 1; in brackets we also report the corresponding percentages obtained from standard ordered logit models (without generalization), estimated for comparative purposes.

A general improvement can be noted in the performance of the estimated generalized models compared to the standard ones and this result strengthens the choice made with regard to the model specification: as a matter of fact, not only does the percentages of correctly predicted responses increase for each response category (except for the second and the fifth), but such percentages become nearly three times greater with reference to the ‘very easy’ category, which is the most difficult to estimate.

We can also note the overall improvement going from the simpler generalized model M1 to the more general M3. This improvement is not simply due to the inclusion of additional predictors, but implies that information supplied by social capital indexes effectively helps to explain subjective perception of poverty.

An improvement also occurs for each response category, except for with some difficulty and very easily; in both cases, in effect, information on social capital seems to produce even slightly worse predictions. On the contrary, the greatest improvement occurs for the first two categories.

From Table 4 of the Appendix, it can be noted that among the socioeconomic characteristics the most relevant influence factors in all equations are the equivalized disposable income (HDI), the presence of a financial burden of the total housing cost (HCO) and the household deprivation status (SMD), as expected. This evidence is coherent with one of the most robust results found in all the empirical literature on the determinants of poverty: a high correlation with income (Easterlin 2001), which always has the strongest explanatory power in econometric analyses (Selnik 2003; Herrera et al. 2006).

It is worth noting that the other most relevant predictors are the social capital indexes referring to territorial context characteristics and social relationships, both of them with a positive effect on the odds. The social behavior index, instead, exerts a less appreciable effect, although positive and significant. It is also interesting to note that in model M2 the global social capital index is the main determinant of subjective poverty.

Marginal effects of each independent variable on probabilities, controlling for the remaining ones, are coherent with expectations and robust across the three models. As a matter of fact, probabilities of with difficulty and with great difficulty in ability to make ends meet increase with age, if the respondent is unemployed, separated/divorced or widowed, if the household is at risk of poverty, severely materially deprived, with debts and financial burden of housing cost, has more than two children, receives income by people aged under 16 and allowances; conversely, these probabilities decrease if the age and the educational level of respondent as well as the dwelling size (in number of rooms) increase.

On the other hand, probabilities of the categories easily and very easily increase if the respondent is working, has a high level of education and the household accommodation is provided free.

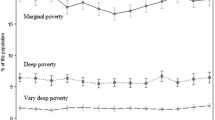

Regarding social capital, both the effect of the overall index in model M2 (see Fig. 1) and the effects of the three sectorial indexes used in model M3 (see Figs. 2, 3, 4) are positive on the probabilities of the categories easily and very easily and negative on the othersFootnote 10; in other words, when social capital endowment grows, European households ability to make ends meet improves. Moreover, in model M3, while Social Relationships (SR) and Territorial Characteristics (TC) indexes show effects rather similar to those of the global index in M2, the Social Behavior (SB) index exerts less evident effects. Indeed, this result is quite coherent with earlier considerations about estimated values and could suggest that the components TC and SR show more support for the dependent variable than SB.Footnote 11

A further proof of the appropriate choice of the generalized specification stems from the fact that the majority of predictors show asymmetric effects on the odds,Footnote 12 that is their effect changes markedly across equations. For example, the effect of the category 5th quintile of HDI (equivalized disposable income) is gradually increasing going from the first equation (referred to with great difficulty) to the last one (referred to very easily); this evidence shows that the strong positive effect of income high levels on the odds becomes much stronger if the odds refer to the higher categories of the dependent variable.

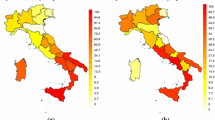

In order to compare the results across the 27 European state members, in Figs. 5 and 6 the probabilities of the categories with great difficulty and, respectively, very easily are plotted by country, in descending order. In particular, Fig. 5 shows that the highest probabilities of the category with great difficulty are detected in Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus. It is interesting to note that Greece also has the highest probability as far as the difficult category is concerned, the lowest values as to the probabilities of the remaining categories and its social capital index value lies below the European average. On the other hand, the countries with the highest probabilities of the category very easily are Sweden, Finland, Netherlands and Denmark (significantly, the corresponding estimated parameters are always positive); we can note that Finland ranks first as to the probabilities of the categories fairly easily and easily, in lower positions in the remaining categories and its social capital index value lies above the European average.

Another example of how differences standing out among European countries can also be ascribed to different social capital endowments refers to estimated probabilities of the category with some difficulty in all the three models: in model M1, countries with higher probabilities are Lithuania, France, Italy, Slovenia and Ireland; in models M2 and M3, which include social capital indexes, Estonia takes the place of Ireland as Irish households on average have, indeed, higher levels of social capital endowment than Estonian ones, both on the whole and with regard to each of its components. This evidence seems to confirm the crucial role that social capital could have in policies and strategies adopted by central and local governments to reduce poverty, as already outlined in Guagnano et al. (2013). Thus, in countries characterized, on average, by poor economic conditions but also by low social capital endowment, policies aimed at poverty reduction could be more effective if they reconciled traditional income support programs with measures which facilitate and encourage the development of desirable forms of social capital.

4 Conclusions

This paper aims at showing if and to what extent self-perceived poverty in European countries is related to household socioeconomic characteristics and household/community social capital endowment in order to disclose the primary risk factors of family poverty status. The analysis proves the existence of a relationship with both groups of possible determinants. If the strong link between household poverty status and socioeconomic characteristics is one of the most well established results found in the empirical literature (Helliwell 2001), the significant relationship between social capital and self-perception of poverty is less obvious and constitutes the core result of the analysis. Hence, not only do household socioeconomic characteristics play a crucial role in affecting self-perception of poverty, but also household/community social capital endowment does. In particular, when household and community social capital endowment increases, European households’ ability to make ends meet improves too. This result has direct and important implications for poverty reduction policies: as a matter of fact, in order to enhance household economic well-being, governments could also facilitate the development of desirable forms of social capital, in addition to the adoption of traditional income support measures. If the EU-SILC survey provided more social capital indicators with greater territorial detail, relationships between social capital and household poverty could be described and captured in their entirety, thus helping policy-makers considerably to promote suitable poverty reduction strategies.

From the statistical point of view, further research should have to cope with the possible endogeneity of social capital indicators, eventually deriving from the measurement errors inherent the use of proxy variables. In this case the research should investigate the possibility of including instrumental variables to obtain consistent estimates and more reliable results.

Notes

Here the focus is on subjective poverty rather than on the wider concept of happiness, which extends beyond pure economic factors and which according to Diener et al. (1999) is a broad category of phenomena that includes people’s emotional responses, domain satisfactions and global judgments of life satisfaction. The term “economics of happiness” is used to refer to studies on aspects of life satisfaction and on their links with different domains of life, including social capital (Diener et al. 1985; Pradhan and Ravaillon 2000; Mc Bride 2001; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Van Praag et al. 2003; Yip et al. 2007; Dolan et al. 2008; Pedersen and Schmidt 2011; Rodriguez-Pose and von Berlepsh 2014).

EU-SILC is the Eurostat project on Income and Living Conditions which involves all the European Union state members. It provides two types of data, cross-sectional and longitudinal over a four- year period (EU-SILC uses a 4-years rotational design).

Some of these variables are not statistically significant and/or have too many missing values and thus they have not been included in the generalized ordered logit models discussed in Sect. 3. They are: low work intensity status, branch of activity, risk of poverty, health, reasons for changing dwelling, work intensity status, alimonies received.

Despite some shortcomings mainly due to the impossibility of measuring all components of social capital, EU-SILC cross-sectional survey and the Eurostat statistic database represent together an important reference source for comparative studies aiming at measuring the effect of social capital on household economic well-being, especially because they provide comparable and high quality cross-sectional indicators for all EU member states. Therefore the EU-SILC survey and the Eurostat statistic database represent an irreplaceable decision-making tool to assess suitable policies aiming at poverty reduction in Europe.

Family workers are persons who help another member of the family to run an agricultural holding or other business, provided they are not considered as employees.

In order to verify this assumption the autofit option of the gologit2 procedure of Stata software has been employed (Williams 2006). This procedure does a series of Wald tests on each variable to see whether its coefficients differ across equations.

The model reduces to the ordinal logit one when the beta coefficients are the same for each j category and the so called proportional odds assumption is satisfied.

The only exception occurs for the class 65–79 of the variable Age; nevertheless we decided to hold this class distinct from the last one, the unique with a positive effect on the odds.

As a matter of fact, it is worth noting that if the dependent variable had only three response categories (with great difficulty or with difficulty; with some difficulty or fairly easily; easily or very easily), the overall percentage of correctly predicted values increases of almost 45–50 % compared to the model with six responses. However, as in such a reduced scale important details are lost, we decided to keep the original six-point scale.

Note that the scale of the vertical axis is showed on the left for the blue lines and on the right for the red ones.

A possible explanation is that among the proxies variables used to form the Social Behavior index there are those referred to rate of crime and perceived violence and vandalism, which in a previous analysis (Guagnano et al. 2013) showed opposite associations with subjective poverty.

The only predictors with invariable effects are: classes 25–29, 60–64 and 65–79 of the variable Age; the categories Medium educational qualification, Payment of a rent for accommodation and all the categories of the following variables: Marital status; Employment status (excepted for inactive); Household type (from the fifth categories until the second last).

References

Abramovitz, M. (1986). Catching up, forging ahead and falling behind. The Journal of Economic History, 46(2), 385–406.

Abramovitz, M., & David, P. A. (1996). Convergence and deferred catch-up: Productivity leadership and the waning of American exceptionalism. In R. Landau, T. Taylor, & G. Wright (Eds.), The Mosaic of economic growth. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Barr, A. (2000). Social capital and technical information flows in the Ghanaian manufacturing sector. Oxford Economic Papers, 52, 539–559.

Bebbington, A., & Perreault, T. (1999). Social capital, development, and access to resources in highland Ecuador. Economic Geography, 75(2), 395–418.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood.

Buttler, F. (2013). What determines subjective poverty? Pre-print of the DFG Research Unit Horizontal Europeanization. Fakultät I · Carl - von - Ossietzky - Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany. http://www.horizontal-europeanization.eu.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2002). Consumption, health, gender and poverty. Working paper Princeton University, 7/02.

Castilla, C. (2010). Subjective poverty and reference-dependence: Income over time, aspirations and reference groups. Working paper World Institute for Development Economics Research, 76/2010, ISBN 978-92-9230-314-3.

Christoforou, A., & Davis, J. B. (2014). Social capital and economics: Social values, power, and social identity. Routledge Advances in Social Economics. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Clemenceau, A., Museux, J. M., & Bauer, M. (2006). EU-SILC (community statistics on income and living conditions): Issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the Eurostat and statistics Finland international conference “comparative EU statistics on income and living conditions: Issues and challenges”, Helsinki, November, 6–8.

Coleman J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94. Supplement: Organizations and institutions: Sociological and economic approaches to the analysis of social structure.

Coleman, J. (1990). Foundation of social theory. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Coleman, J., Katz, E., & Menzel, M. (1966). Medical innovation: A diffusion study. New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

Collier, P. (1998). Social capital and poverty. Social capital initiative working paper no. 4. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cracolici, M. F., Giambona F., & Cuffaro M. (2011). Composition of families and subjective economic well-being. An application to Italian context. ECINEQ working paper no. 195, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality.

Cracolici, M. F., Giambona, F., & Cuffaro, M. (2012). The determinants of subjective economic well-being: An analysis of Italian-Silc data. Applied Research Quality Life, 7, 17–47. doi:10.1007/s11482-011-9140-z.

Deutsch, J., & Silber, J. G. (2005). Measuring multidimensional poverty: An empirical comparison of various approaches. The Review of Income and Wealth, 51(1), 145–174.

Diener, E., Horwitz, J., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Happiness of the very wealthy. Social Indicators Research, 16, 263–274.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three deades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1203–1250.

Eurostat. (2009). EU-SILC 065 (2009 operation). Description of target variables: Cross-sectional and longitudinal 2009 operation (Version January 2010).

Eurostat. (2010). Income and living conditions in Europe. Luxembourg: Anthony B. Atkinson and Eric Marlier (Eds.).

Fernandez, R. M., Castilla, E. J., & Moore, P. (2000). Social capital at work: Networks and employment at a phone center. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1288–1356.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fu, V. (1998). Estimating generalized ordered logit models. Stata Technical Bullettin, 44, 27–30.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: Social virtues and the creation of prosperity. NY: Free Press.

Galor, O., & Zeira, J. (1993). Income distribution and macroeconomics. Review of Economic Studies, 60(1), 35–52.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital. The Economic Journal, 112, 437–458.

Goedemé, T., & Rottiers, S. (2011). Poverty in the enlarged European Union. A discussion about definitions and reference groups. Sociology Compass, 5(1), 77–91.

Goedhart, Th, Halberstadt, V., Kapteyn, A., & Van Praag, B. M. S. (1977). The poverty line: Concept and measurement. The Journal of Human Resources, 12, 503–520.

Granovetter, M. S. (1995). Getting a job: A study of contacts and careers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Green, A., Preston, J., & Sabates, R. (2003). Education, equality and social cohesion: A distributional approach. Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education, 33(4), 453–470.

Grootaert, C. (1999). Social capital, household welfare and poverty in Indonesia. Local level institutions working paper no. 6. The World Bank Social Development Family Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, April.

Grootaert, C., Gi-Taik, O., & Swamy, A. (1999). The local level institutions study: Social capital and development outcomes in Burkina Faso. Local level institutions working paper no. 7. The World Bank Social Development Family Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, September.

Grootaert, C., & van Bastelaer, T. (2001). Understanding and measuring social capital: A synthesis of findings and recommendations from the social capital initiative. Social capital initiative working paper no. 24. Washington DC: World Bank.

Grootaert, C., & van Bastelaer, T. (2002). The role of social capital in development: An empirical assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guagnano, G., Santarelli, E., & Santini, I. (2013). The role of social capital in self-perception of poverty. An exploratory analysis. Annals of the Department Methods and Models for Economics, Territory and Finance. Bologna: Patron (forthcoming).

Hassan, R., & Birungi, P. (2011). Social capital and poverty in Uganda. Development Southern Africa, 28(1), 19–37. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2011.545168.

Hayo, B., & Seifert, W. (2003). Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 329–348.

Helliwell, J. F. (2001). Social capital, the economy and well-being. In K. Banting, A. Sharpe, & F. St-Hilaire (Eds.), The review of economic performance and social progress (pp. 55–60). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy and Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

Herrera, J., Razafindrakoto, M., & Roubaud F. (2006). The determinants of subjective poverty: A comparative analysis in Madagascar and Peru. Working papers DT/2006/01, DIAL (Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation Montreal and Ottawa: Institute for Research on Public Policy and Centre for the Study of Living Standards).

Knack, S. (1999). Social capital, growth and poverty: A survey of cross-country evidence. Social capital initiative working paper no. 7. Washington: World Bank.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have and economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Letki, N. (2006). Investigating the roots of civic morality: Trust, social capital, and institutional performance. Political Behavior, 28, 305–325. doi:10.1007/s11109-006-9013-6.

Levesque, M. (2005). Social capital, reducing poverty and public policy. Social capital in action. Thematic policy studies. PRI Project Social Capital as a Public Policy Tool, September, Canada.

Loopmans, M. (2001). Spatial structure and the origin of social capital: A geographical reapproach of social theory. In Proceedings of the congress on social capital: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Exeter, 15–20 September, pp. 41–60.

Maluccio, J., Haddad, L., & May, J. (2000). Social capital and Household Welfare in South Africa 1993–98. Journal of Development Studies, 36(6), 54–81.

Massoumi, E. (1986). The measurement and decomposition of multidimensional inequality. Econometrica, 54, 991–997.

Mc Bride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 45, 251–278.

Mc Cullogh, P., & Nelder, J. A. (1989). Generalized linear model (2nd ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

Narayan, D. (1999). Bonds and bridges. Social capital and poverty. New York: Poverty Group, World Bank.

Narayan, D., & Pritchett, L. (1999). Cents and sociability: Household income and social capital in rural Tanzania. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(4), 871–897.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions. Institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olken, B. A. (2006). Do television and radio destroy social capital? Evidence from Indonesian villages. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(4), 1–33.

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation and social rigidities. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pedersen, P. J., & Schmidt, T. D. (2011). Happiness in Europe: Cross-country differences in the determinants of satisfaction with main activity. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(5), 480–489.

Peterson, B., & Harrel, F. E. (1990). Partial proportional odds models for ordinal response variables. Applied Statistics, 39(2), 205–217.

Pradhan, M., & Ravaillon, M. (2000). Measuring poverty using qualitative perceptions of consumption adequacy. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(3), 462–471.

Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Shuster.

Putnam, R., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ravaillon, M., & Lokshin, M. (2002). Self-rated economic welfare in Russia. European Economic Review, 46, 1453–1473.

Reimer, W. (2002). Understanding social capital: Its nature and manifestations in rural Canada. A paper prepared for presentation at the CSAA annual conference, Toronto.

Rodriguez-Pose, A., & von Berlepsh, V. (2014). Social capital and individual happiness in Europe. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(2), 357–386.

Rose, R. (1999). What does social capital add to individual welfare? An empirical analysis of Russia. Social capital initiative working paper no. 15. The Washington: World Bank.

Roslan, A.-H., Russayani, I., & Azam, N. A. A. (2010). Does social capital reduce poverty? A case study of rural households in Terengganu, Malaysia. European Journal of Social Sciences, 14(4), 556–566.

Santini, I., & De Pascale, A. (2012a). Social capital and its impact on poverty reduction: Measurement issues in longitudinal and cross-country comparisons. Towards a unified framework in the European Union. Working paper Department of Methods and Models for Economics, Territory and Finance, SAPIENZA University of Rome, 101.

Santini, I., & De Pascale, A. (2012b). Social capital and household poverty in Europe. Working paper Department of Methods and Models for Economics, Territory and Finance, SAPIENZA University of Rome, 109.

Selnik, C. (2003). What can we learn from subjective data? The case of income and well-being. Delta working paper, 06/2003, Paris.

Sen, A. (1982). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlements and deprivation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. (2000). Social exclusion: Concept, application and scrutiny. Social development papers no. 1. Office of Environment and Social Development Asian Development Bank, June.

Stanovnik, T., & Verbic, M. (2004). Percption of income satisfaction. An analysis of Slovenian households. HEW 0408003, EconWPA.

Tiepoh, M. G. N., & Reimer, B. (2004). Social capital, information flows and income creation in rural Canada: A cross-community analysis. Journal of Socio-Economics, 33, 427–448.

Tomlinson, M., Walker, R. & Williams, G. (2007). Measuring poverty in Britain as a Multidimensional Concept. Barnett papers in Social Research-University of Oxford, 7.

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2006). A multi-dimensional approach to subjective poverty. In S. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), Quantitative approaches to multidimensional poverty measurement. Palgrave MacMillan: Houndmills.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Fritjers, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(1), 29–49.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Fritjers, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). A multidimensional approach to subjective poverty. In Proceedings of the international conference on the many dimensions of poverty, Brasilia, 29–31 August.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Goedhart, Th, & Kapteyn, A. (1980). The poverty line—A pilot survey in Europe. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(3), 461–465.

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Van der Sar, N. (1988). Empirical uses of subjective measures of well-being: Household cost functions and equivalence scales. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(2), 193–210.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2009). Europeanization of inequality and European reference groups. Journal of European Social Policy, 19(2), 117–130.

Williams, R. (2006). Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. Stata Journal, 6(1), 58–82.

Woolcock, M. (2002). Social capital in theory and practice: Where do we stand? In J. Isham, T. Kelly, & S. Ramaswamy (Eds.), Social capital and economic development: Well-being in developing countries. Cheltenhem: Edward Elgar.

Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Research Observer, 15(2), 225–249.

Yip, W., Subramanian, S. V., Mitchell, A. D., Lee, D. T. S., Wang, J., & Kawachi, I. (2007). Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 35–49.

Yusuf, S. A. (2008). Social capital and household welfare in Kwara State, Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology, 23(3), 219–229.

Acknowledgments

The present work has been developed within the research “Perception of poverty. Individual, household and social environmental determinants” led by Isabella Santini at SAPIENZA University of Rome, partially supported by 2010 Italian M.I.U.R. grants (Prot. C26A10WW49).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 2.

Appendix 2

See Table 3.

Appendix 3

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guagnano, G., Santarelli, E. & Santini, I. Can Social Capital Affect Subjective Poverty in Europe? An Empirical Analysis Based on a Generalized Ordered Logit Model. Soc Indic Res 128, 881–907 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1061-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1061-z