Abstract

This main purpose of this study tests whether a higher-order gratitude compassing multi-components (e.g., thank others, thank God, cherish blessings, appreciate hardship, and cherish the moment) explains variances in subjective well-being including life satisfaction and positive affect after controlling for gender, age, religion, the Big Five personality traits (e.g., openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism), and a single gratitude. A total of 504 undergraduate participants were recruited to completed five inventories measuring the variables of interest. The higher-order gratitude made a significant unique contribution to life satisfaction (10 % of the variance, p < .001) and positive affect (2 % of the variance, p < .001) beyond the effects of demographic variables, the Big Five personality traits, and a single gratitude. This is consistent with the theoretical stance that the higher-order gratitude is more than just the Big Five personality traits or a single gratitude and is important in its own right for subjective well-being. Furthermore, it implies a multi-components gratitude is in deed different from a unifactorial gratitude and it seems more reasonable that trait gratitude is a higher-order construct including lower-order components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Positive psychology is one of the most influential trends in modern psychological science (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000; Sheldon and King 2001). It emphasizes to redress the imbalance and increase scientific attention and resources to studies of human positives, human striving, achievements, potentialities, and quality of life (Seligman 2003; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000; Wood and Tarrier 2010). Consequently, there have been great renewed interests in studies of subjective well-being (Diener et al. 1999; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005), personal or character strengths (McCullough and Snyder 2000; Peterson and Seligman 2004), and how these character strengths can be used to increase or enhance subjective well-being (Linley and Harrington 2006; Wood et al. 2011).

Specifically, the study of character strengths and the development of a classification of strengths and virtues are major initiatives of the positive psychology movement. In this connection, Peterson and Seligman (2004) have attempted classifications of 24 character strengths grouped under six overarching virtues that are claimed to be shared across culture and human history (Dahlsgaard et al. 2005). It is argued that character strengths are natural capacities within individuals, and these strengths, when cultivated and promoted, would allow individuals to achieve optimal functioning and performance, and lead individuals to have better, more satisfying, and more fulfilling life (Linley and Harrington 2006).

Numerous studies have also suggested that character strengths are associated with subjective well-being, and specific character strengths can contribute significantly to the prediction of subjective well-being. In a pioneering study, Park et al. (2004) surveyed 5,299 adults using the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths and found that hope, zest, gratitude, love, and curiosity were consistently and robustly associated with life satisfaction. These findings of linkage between individual strengths and life satisfaction have subsequently been extended to findings in other settings that include the United Kingdom (Linley et al. 2007), Switzerland (Peterson et al. 2007), Japan (Shimai et al. 2006), and Croatia (Brdar and Kashdan 2010).

Notably, gratitude has become one of the most central concepts within positive psychology. There are some reasons explaining why gratitude is important. First, gratitude upgrades people’s individual lives threefold in emotion, cognition, and action. For emotion, has demonstrated that the more grateful one is, the happier one will be (McCullough et al. 2004; Wood et al. 2010). For cognition, gratitude provides us a more optimistic point of view toward our own experiences (McCullough et al. 2004), relationships (Gordon et al. 2011), and others’ personalities and behaviors (McCullough et al. 2004). Moreover, in terms of action, it is widely accepted that gratitude enhances our prosocial tendency toward benefactors (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006; Tsang 2006) and even for unknown third parties (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). Finally, empirical studies have shown that gratitude is a predictor of well-being (e.g., Emmons and McCullough 2003; Hill and Allemand 2011; Martínez-Martí et al. 2010; McCullough et al. 2002, 2004; Nelson 2009; Park et al. 2004; Wood et al. 2007). To summarize, gratitude occupies the center of positive psychology for its uniqueness to advance our emotional, cognitive, behavioral existence, and well-being.

1.1 Is Gratitude Just a Unifactorial Structure?

Gratitude is the disposition to feel and express thankfulness consistently over time and across situations (Emmons and Crumpler 2000). McCullough et al. (2002) defined the grateful disposition as “a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (p. 112). Accordingly, they developed the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ)-6 questionnaire to assess gratitude as a single factor, based on four different facets of grateful disposition that include intensity, frequency, span and density. In other words, grateful people may feel gratitude more intensely for a positive event, and may report gratitude more frequently or more easily throughout the day. They may have a wider span of life circumstances for which they are grateful at any given time with a variety of other benefits (e.g., for their families, their jobs, their health and life itself), and they may experience gratitude with greater density (e.g., towards more people) for a single positive outcome or life circumstance.

Recently, Wood et al. (2010) considered that gratitude is part of a wider life orientation towards noticing and appreciating the positive in the world and evidence for this wider conceptualization of gratitude had been provided by Wood et al. (2008c). For example, some people seem to cherish each new day, notice acts of kindness, acknowledge the sacrifices of others, and be thankful for every privilege or positive aspect of their lives. Yet others fail to notice or appreciate the positive aspects of their lives and the sacrifices of others on their behalf. They take for granted much of what they experience, encounter, or rely upon, and they may exhibit a sense of entitlement. This observation suggests that grateful individuals may have a variety of experiences of thankful appreciation because of different sources of gratitude. In this line, they suggested that gratitude is a higher-order factor compassing different components, implying that the grateful personality involves different aspects. That is, trait gratitude seems not to be unifactorial, such as GQ-6. Accordingly, Lin and Yeh (2011) developed the Inventory of Undergraduates’ Gratitude (IUG) based on its multi-components and viewed gratitude as a higher-order construct including five aspects (lower-order components) (see Table 1).

The first aspect is the “thank others” which not only noticing a benefit received (gifts, perceived efforts, sacrifices/actions on one’s behalf) and feeling grateful to someone for it, but also valuing the people in one’s life and the contribution that relationships make to one’s life and well-being and expressing that. The second one is “thank God” which refers to feeling a deep emotional, spiritual, or transcendental connection to something, such as a stunning vista, a forest of Redwoods, or birth of a baby. The third one is “cherish blessings” which is focusing on what one has rather than lacks. What one has includes material possessions and also such things as one’s health or opportunities. The fourth one is “appreciate hardship” which refers to using one’s perceived losses, experiences of adversity, or close calls to promote appreciating the positive aspects of one’s life. Finally, the “cherish the moment” is engaging in mindful awareness of the “here and now,” one’s surroundings and their positive qualities (Lin and Yeh 2011).

Emmons and Crumpler (2000) stated that “gratitude is a relational virtue that involves strong feelings of appreciation toward significant others” (p. 58). The “significant other” can be a person, a God, or any other material or spiritual entity. In this line, we suggested that unifactorial gratitude seems similar to “thank others” and “thank God” of higher-order gratitude. It implied that unifactorial gratitude may not be well-structured because it didn’t include the other aspects of higher-order gratitude. One of Chinese proverbs states “Happiness lies in contentment,” or “A contented mind is perpetual feast.” (知足常樂) which means we must learn to be content with what we have now in order to obtain everlasting well-being. This belief is especially quiet important and influential in Asian culture. For Chinese ethics, people lead a living accompanied by this kind of wisdom for the whole life. This observation suggests that higher-order gratitude including different dimensions may be more meaningful and valuable compared to unifactorial gratitude.

1.2 Gratitude, Subjective Well-Being and Personality

Subjective well-being is defined as the affective and cognitive evaluation of life (Diener 1984; Diener and Lucas 2000). Despite that different researchers have used the term subjective well-being in slightly different ways, they tend to accept that it generally involves the subjective evaluation of one’s current status in the world (Snyder and Lopez 2007). Specifically, Diener et al. (2002) redefined subjective well-being as a combination of general life satisfaction and the presence of positive affect, and is often summarized as happiness (Brulde 2007; Karlson et al. 2013).Given this view, subjective well-being includes cognitive and affective components, the former is life satisfaction and the latter is positive affect. This structure of subjective well-being has received empirical support in subsequent studies (e.g., Arthaud-Day et al. 2005; Diener et al. 2002). The research has shown that these dimensions are closely related to both positive indicators of mental health such as self-esteem, psychological well-being, and extraversion (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 2003; Ryff and Keyes 1995), and negative indicators such as depression, anxiety, and neuroticism (Lonigan et al. 2003; Diener 1984).

Throughout history, religious, theological, and philosophical treatise have viewed gratitude as integral to well-being (Emmons and Crumpler 2000; Harpman 2004). Conceptually, gratitude should be expected to be strongly related to well-being. Gratitude represents the quintessential positive personality trait, being an indicator of a worldview orientated towards noticing and appreciating the positive in life (Wood et al. 2008c). Empirically, gratitude is a strong predictor of subjective happiness or a sense of well-being (e.g., Froh et al. 2009; Nelson 2009; Toussaint and Friedman 2009; Wood et al. 2008a, 2010). Numerous studies have established the connection between gratitude and well-being. For example, studies have indicated that gratitude was incompatible with negative emotions and pathological conditions, and could even offer protection against psychiatric conditions. Specifically, gratitude has been found to relate positively with optimism and hope, and negatively with depression, anxiety and envy in nonclinical samples (McCullough et al. 2002). Moreover, Hill and Allemand (2011) found that grateful and forgiving adults reported greater well-being in adulthood. Similarly, Watkins et al. (2003) found that individuals who scored higher in grateful personality traits reported more life satisfaction, higher subjective well-being and more positive emotions than their counterparts. Experimental studies have also found that gratitude interventions significantly improved individuals’ well-being. Emmons and McCullough (2003) found that a gratitude journal intervention improved the well-being of college students and adults with neuromuscular disorders. Seligman et al. (2005) found that a gratitude exercise successfully increased happiness over a long period of time. Chan (2010) also found that an intervention program of 8-week count-your-blessings promoted teachers’ life satisfaction. These empirical findings suggest that there is a causal relationship between gratitude and well-being. In particularly, large numbers of researches have almost focused on subjective well-being.

However, it is not clear whether the relationship between gratitude and subjective well-being is unique, or whether gratitude is simply related to subjective well-being due to a third personality variable. For example, gratitude could simply be related to subjective well-being because of the more general relationship between subjective well-being and positive emotions. In their seminal paper on trait gratitude, McCullough et al. (2002) argue that as the last 50 years have lead to a proliferation of personality measures, it is necessary to show that gratitude effects outcome measures after controlling for other more widely researched traits.

In recent years, the Five Factor Model (McCrae and Costa 1999) has achieved a widespread acceptance in personality psychology. There is now reasonable consensus that the Big Five domains of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism represent most of personality at the highest level of abstraction (Goldberg 1993; John and Srivastava 1999). These variables cover the breadth of personality, including positive and negative affect (respectively, existing under extraversion and neuroticism), and pro-social traits (under agreeableness). As may be expected from a social and well-being variable, some studies further have proven that gratitude is positively correlated with extraversion, agreeableness and negatively correlated with neuroticism (e.g., Lin and Yeh 2011; McCullough et al. 2004, Wood et al. 2008a, b, c); together the Big Five variables explain between 21 % and 28 % of the variance in gratitude (McCullough et al. 2002).Moreover, the Big Five variables are correlated with subjective well-being (Ana et al. 2012; Andreja et al. 2011; DeNeve and Cooper 1998; Steel et al. 2008) raising the possibility that gratitude is only linked to subjective well-being because of the third variable effects of the Big Five. That is, the third variable effects of the Big Five thus offer an alternative explanation of why gratitude is related to subjective well-being. Demonstrating that gratitude is related to subjective well-being above the effects of the Big Five is an important test of theoretical perspectives which see gratitude as a unique aspect of well-being (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005; Watkins 2004). The Big Five traits represent some of the most studied variables over the last 50 years (Goldberg 1993; John and Srivastava 1999). McCullough et al. (2002) argued that for gratitude research to have an impact on personality psychology it is necessary to show that the variable has incremental validity above the effects of the Big Five personality traits.

1.3 The Present Study

To realize whether gratitude have a unique impact on personality psychology, it is necessary to show that gratitude can explain variance in outcome variables above the Big Five personality traits. Moreover, whether gratitude ought to be viewed a higher-order/multi-components or just a single/unifactorial construct seems to be controversial. If we can distinguish their contributions to important outcome variables (e.g., subjective well-being), may we clarify their differences and answer the above question.

In addition, despite growing interest in gratitude and subjective well-being, most studies were examined in the United States. Few studies have investigated gratitude and its association in Asian or African culture. Chinese people represent for example 20 % of the world’s population whereas the United States population is five times smaller. In fact, researchers have recently called attention to the fact that although the United States represents only a small proportion of the world’s population, too many psychological research is on individuals from the United States. The narrowness of the sample upon which most psychological research has been conducted raises important questions about the generalizability of this research (Arnett 2008; Heine and Buchtel 2009). Furthermore, gratitude is deeply embedded in cultural frameworks (Cohen 2006). In this study, we sought to address this gap by examining the relationship between gratitude and subjective well-being and further exploring the issue: does a multi-components gratitude contribute unique variance to subjective well-being (including life satisfaction and positive affect), beyond demographic variables, the Big Five personality factors, and a unifactorial gratitude?

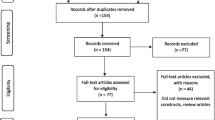

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

The study participants included 504 Taiwanese university students including freshman to senior from general education courses in six universities. These courses are elective for students and they can choose which is interested in on their own. Student enrolled general education courses were from a variety of colleges (e.g., liberal arts, science, engineering, management, social science, business, and medicine) and different departments in each university. We selected these courses and students as representative of university students because of the diversity. Of the total, 51.4 % of the participants were from private universities, and 48.6 % of the participants were from public universities. With a mean age of 20.21 years (SD = 1.02), the participants included 176 males (34.9 %) and 328 females (65.1 %). Moreover, 190 participants (37.7 %) have religious affiliations and 314 ones (62.3 %) doesn’t.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Higher-Order Gratitude

The IUG (Lin and Yeh 2011) was employed to measure the participants’ higher-order gratitude in this study. With a total of 26 items (see Table 1 for sample items), the scale included five factors: thank others (7 items), thank God (5 items), cherish blessings (5 items), appreciate hardship (5 items), and cherish the moment (4 items). Lin and Yeh reported sound psychometric properties of the scale, including a robust five-factor structure through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, and reasonable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α were .93 for IUG, and ranged from .74 to .84. for the five factors listed above). In completing the scale, participants were requested to indicate their judgement as to whether the statement in each item was descriptive of them using a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

2.2.2 Single Gratitude

The Chinese version of the GQ (Chen et al. 2009) was employed to measure the participants’ single gratitude in this study. Chen et al. translate and validate the GQ (McCullough et al. 2002) in Chinese. Confirmation factor analysis indicated that a five item model was a better fit than the original six item model. Cross-validation also supported the modified Chinese version of the GQ. In addition, the Chinese version of the GQ was, as expected, positively correlated with optimism, happiness, agreeableness, and extraversion, which supported its construct validity. Moreover, the Cronbach’s α was .80 for the Chinese version of the GQ, indicating satisfactory validity and reliability. In completing the scale, participants were requested to indicate their judgement as to whether the statement in each item was descriptive of them using a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The test items included statements such as “I am grateful to a wide variety of people.”

2.2.3 Big Five Personality Trait

The Chinese Big Five personality scale (Chuang and Lee 2001) was employed to measure the participants’ types of personality in this study. Based on the fundamental lexical hypothesis (Goldberg 1990), Chuang and Lee collected 148 Chinese adjectives, formed a scale, and administrated it to teachers of elementary school students. EFA from teachers’ ratings of students indicated that these adjectives could be clustered into five categories that correspond to the Big Five (e.g., openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) model. Chuang and Lee reported satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ranged from .78 to .94 for five factors) and a 1-year test and retest reliability. Chen (2004) modified the Chinese Big Five personality scale into a shorter version and administered it to a teacher sample. Factor analysis indicated that the short version of the Chinese Big Five personality scale maintained the five factor structure and produced acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α ranged from .60 to .86 for five factors). In completing the scale, participants were requested to indicate their judgement as to whether each of the five statements was descriptive of them using a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

2.2.4 Life Satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985) was employed to measure the participants’ general life satisfaction as the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being in this study. It reveals the individual’s own judgement of his or her quality of life. The scale consists of five items and has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α is .87), excellent 2-month test–retest reliability (r = .82), and convergent and discriminant validity with other measures of subjective well-being, independent ratings of life satisfaction, self-esteem, clinical symptoms, neuroticism and emotionality (Diener et al. 1985; Lucas et al. 1996; Pavot and Diener 1993). In completing the scale, participants were requested to indicate their judgement as to whether each of the five statements was descriptive of them using a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The test items included statements such as “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.”

2.2.5 Positive Affect

The Long-term Affect (Diener et al. 1995) is revised to measure the participants’ positive affect in this study. Based on interest and need of research, we choose positive affect scale including 8 items from the original scale. In the preliminary study, the 8 items were tested converge to one single factor including 5 items through EFA. The scale has good reliability (Cronbach’s α is .90) and has also shown good construct validity through CFA. In completing the scales, participants were requested to make their judgements of experiencing the emotions in general on a 6-point scale ranging from “never” to “always”.

2.2.6 Demographic Information

Participants completed demographic questions such as gender, age, and religious affiliation. Previous studies suggested some demographic variables had effects on person’s gratitude such as gender (e.g., Kashdan et al. 2009; Lin and Yeh 2011), age (e.g., McAdams and Bauer 2004), and religion (e.g., Lin and Yeh 2011; McCullough et al. 2002). Thus, these data were selected as controlled variables to conduct following analyses.

2.3 Procedures and Data Analyses

In order to recruit the university students for this study, we contacted the university teachers and asked their consents. Students were invited to fill out a few questionnaires voluntarily during regular class sessions. Participants took approximately 10 min to complete the whole survey. While finishing the questionnaires, students hand them out for a research assistant on the class.

The first step in the analyses comprises preliminary analyses, including descriptive statistics on the independent and dependent variables, intercorrelations and reliability between all the variables.

To assess whether the high-order gratitude accounted for unique variance in criteria, subjective well-being, the second step in the analyses examines the additive contributions of the variables in predicting life satisfaction and positive affect. We conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses, by adding demographic variables, the Big Five personality factors, and a unifactorial gratitude in each of three steps as control variables, followed by a multi-components gratitude in a fourth step. In other words, four hierarchical regression models were tested. Moreover, the fourth model of a hierarchical regression model in which the gender, age, and religion composed the first block, personality factors the second, and single gratitude score the third is our concern.

3 Results

The item responses of the 504 participants to all measures were first aggregated to yield thirteen scores based on the five subscales of the IUG, Chinese GQ, the five subscales of Chinese Big Five personality scale, and two scales of subjective well-being (e.g., life satisfaction and positive affect). Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and internal consistency of these scales, together with the correlation matrix of these measures. It can be seen that the coefficients alpha as indices of internal consistency of these scales were of moderately high values, ranging from .73 to .88, suggesting that these variables were all reliably assessed.

Multi-components gratitude and unifactorial gratitude correlated substantially and significantly with each other, and particularly with Big Five personality traits, and with two measures of subjective well-being. The pattern of correlations suggested that the more grateful the person, the more likely the person would be tend to grant openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, relatively less neuroticism, and experience greater life satisfaction, more positive emotions.

To further explore and evaluate the separate contribution of demographic variables, Big Five personality traits, unifactorial gratitude, and multi-components gratitude to the prediction of subjective well-being, two sets of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, using these variables as four ordered sets of predictors to predict separately the two criterion variables of subjective well-being. All tolerance values exceeded .10 (and VIFs <10) indicating no problems with multicollinearity (Meyers et al. 2006). Also, the largest correlation between predictors was .78, less than .8, the heuristic figure suggesting possible multicollinearity (Meyers et al. 2006). These results are summarized in Table 3.

Demographic variables, though not expected to contribute to subjective well-being, were entered first (Step 1) to allow comparison with the contribution of the other variables of interest in subsequent analyses. It can be seen that age significantly predict subjective well-being, but gender and religion didn’t, in the meantime, they accounted for only 2–3 % of the variance in the criterion variables. Big Five personality traits added (Step 2) to the prediction with an incremental 24 % for life satisfaction and 32 % for positive affect, resulting in significant prediction of life satisfaction and positive affect by the joint contribution of demographic variables and Big Five personality traits. The addition of unifactorial gratitude (Step 3) resulted in significant prediction of criterion variables, with incremental contributions of 4 % for life satisfaction and 4 % for positive affect. The further addition of multi-components gratitude (Step 4) resulted in significant prediction of criterion variables, with incremental contributions of 10 % for life satisfaction and 2 % for positive affect. Notably, while unifactorial gratitude emerged as a significant predictor in predicting life satisfaction and positive affect before multi-components gratitude was entered as a predictor (Step 3), multi-components gratitude emerged as a stronger predictor when both unifactorial gratitude and multi-components gratitude were entered in the prediction (Step 4). These results suggested multi-components gratitude makes a significant uniquely contribution to subjective well-being, even after controlling for gender, age, and religion, Big Five personality factors, and unifactorial gratitude.

4 Discussion

Results support the importance of the Big Five personality traits, a unifactorial gratitude and a multi-components gratitude for subjective well-being. The Big Five personality traits accounted for about 24 % for life satisfaction and 32 % for positive affect, over-and-above gender, age, and religion. A unifactorial gratitude added another 4 % for each of them. A multi-components gratitude explained another 10 % of the variance in life satisfaction and 2 % of the variance in positive affect after controlling for demographic variables, Big Five personality traits and unifactorial gratitude, as measured by Chinese version of the GQ. Such values are conventionally interpreted as substantial incremental validities (Hunsley and Meyer 2003). Moreover, this is consistent with the theoretical stance that a multi-components gratitude is more than just a unifactorial gratitude or Big Five personality traits and is important in its own right for subjective well-being.

The significant contribution of gratitude replicates and extends the results of Wood et al. (Wood et al. 2008a). Current results provide additional support for their finding, as the same result was obtained even after controlling for gender, age and a different instrument measured the Big Five personality traits. Furthermore, another variance in subjective well-being explained by a multi-components gratitude is more than a unifactorial gratitude, it implies a multi-components gratitude is in deed different from a unifactorial gratitude and it seems more reasonable that trait gratitude is a higher-order construct including lower-order components. Compared to unifactorial gratitude, the higher-order gratitude construct appears to cover the full breath of the people, events, and all kinds of sources which people report eliciting gratitude, explaining the studies where people reported gratitude towards non-social sources (e.g., Emmons and McCullough 2003; Veisson 1999; Weiner et al. 1979). These factors also seem to widen the definition of gratitude more than the construct has previously been considered (e.g., “thank others” and “thank God”). The higher-order construct appears to represent a “wider life orientation towards the positive” (Wood et al. 2009a, p. 43) involving a “broaden worldview towards noticing and appreciating the positive in life” (e.g., “cherish blessings”, “appreciate hardship”, and “cherish the moment”) (Wood et al. 2009b, p. 443). The life orientation towards noticing a appreciating the positive in life is considered a trait (dispositional) tendency.

Notably, among the higher-order gratitude, “Cherish blessings” was not only the strong predictor predicting the life satisfaction, but also the strong one predicting the positive affect after controlling for demographic variables, Big Five personality traits and unifactorial gratitude. When an individual is grateful for the greenness of his or her own lawn, he or she is not likely to be looking at the greener grass on the other side of the fence. In other words, grateful individuals should have a sense of abundance, they wouldn’t feel deprived in life. It represents a focus on what we have rather than on what we lack. “Cherish blessings” is noticing, acknowledging, and feeling good about (e.g., appreciating) what we have in our lives. “What we have” refers to anything we experience as “being with us” or “connected to us” in some meaningful way. The result is consistent with a Chinese proverb states “Happiness lies in contentment,” or “A contented mind is perpetual feast.” which means if a person would focus on what he or she has (rather than lacks) and valuing it, he or she would be happier and obtain everlasting well-being.

In addition, the unexpected finding is that “thank others” correlates positively with any of the DVs (e.g., life satisfaction and positive affect) (rs = .31–.42) in terms of Pearson r. However, when one of the DVs such as life satisfaction is regressed on the five high-order gratitude subscales, “thank others” appears to function as a suppressor. That is, “thank others” suppresses the variance in high-order gratitude that is irrelevant to life satisfaction. At this point, one can only speculate about the possible sources of variance tapped by the scale that could underlie such suppression. For example, it may be that gratitude is deeply embedded in cultural frameworks (Cohen 2006). Compared with those from individualistic cultures (e.g., the United States), people in collectivistic cultures appear to tie gratitude to indebtedness and obligation to reciprocate others to a greater degree (e.g., Chinese culture) (Cohen 2006; Kee et al. 2008). As one of the Chinese proverbs states “a drop of water shall be returned with a burst of spring” (滴水之恩,當涌泉相報), which means to return the favor with all you can when others are in need, even if it was just a little help from others.

Greenberg (1980) defined indebtedness as a state of obligation to repay another (p. 4), which arises from the norm of reciprocity, a moral code stating that “(1) people should help those who have helped them, and (2) people should not injure those who have helped them” (Gouldner 1960, p. 171). In other words, the theory of indebtedness states that when an individual receives a benefit from another, he or she feels obligated to reciprocate the favor (e.g., Gouldner 1960; Regan 1971; Whatley et al. 1999). In this line, it may be happened in Chinese culture because its conventional moralities and ethics. Moreover, indebtedness is accompanied by negative emotions such as discomfort and uneasiness (e.g., Greenberg 1980). A study in Hong Kong had been found that indebted students, compared with less indebted students, reported less satisfaction with life, but no difference in positive affect (Zhao 2012). This observation suggests that in Chinese societies, “thank others” may help to maintain harmony within the group by creating and nurturing interpersonal relations based on moralities, but it may also elicit more feelings of indebtedness to lead to one’s psychological distress and in turn decrease his degree of life satisfaction or do harm to his subjective well-being.

5 Conclusions and Suggestions

The major finding regarding higher-order gratitude as a predictor of subjective well-being is that when the contributions of demographic variables, the Big Five personality traits, and a single gratitude are partialled out, higher-order gratitude still makes a significant contribution to two components of subjective well-being: life satisfaction and positive affect, Thus, demographic variables, the Big Five personality traits, and a single gratitude do not account for the ability of higher-order gratitude to predict life satisfaction or positive affect. This study provides evidence that higher-order gratitude accounts for aspects of subjective well-being that the other constructs do not. This finding has major implications for future research regarding subjective well-being and the development of higher-order gratitude as a unique and valuable construct.

The study had some limitations, particularly the reliance on self report. Arguably, self reports should be considered the primary source of data for subjective evaluation of wellbeing and character strengths. However, other sources such as peer reports or behavioral ratings (cf., Tsang 2006), which could provide convergent and therefore more compelling evidence, should be considered in future studies. One another limitation is that the participants in this study were all university students and research has indicated that levels of gratitude vary with age (McAdams and Bauer 2004). Thus, this might constrain the generalization of these findings to different aged populations. Likewise, with positive psychology constructs increasingly being considered in clinical settings (Duckworth et al. 2005), we encourage tests of whether a multi-components gratitude contributes unique variance to subjective well-being in diverse populations. On the other hand, these results are founded in Chinese culture, so they should be verified in different cultures such as western nations to confirm whether a multi-components gratitude is valid and further contributes unique variances to subjective well-being in other countries. Moreover, future research could also examine whether a multi-components gratitude makes a unique contribution to psychological well-being, which differs from subjective well-being (Ryff 1989), involves such traits as involving autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance (Ryff and Keyes 1995). While most previous research has focused on subjective well-being constructs, such as life satisfaction and positive affect, future research should consider whether gratitude can provide incremental validity in explaining psychological well-being. Further, it seems likely that some aspects of a multi-components gratitude will be more closely related to some components of psychological well-being than others. For example, it seems likely that the “thank others” is more closely tied to positive relations with others than the other aspects of a multi-components gratitude and the “appreciate hardship” is more closely tied to personal growth than the other aspects of a multi-components gratitude. In this way, we’ll be more confident to announce the incremental validity of a multi-components gratitude and is more than just a unifactorial gratitude, and the value and meaning of a multi-components gratitude will help us re-consider the essence of gratitude, even further re-examine previous researches by implement the construct of a high-order gratitude.

References

Ana, B., Irma, B., & Denis, B. (2012). Predicting well-being from personality in adolescents and older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 455–467.

Andreja, B.-Ž., Danijela, I., & Kaliterna, L. L. (2011). Personality traits and social desirability as predictors of subjective well-being. Psychological Topics, 20(2), 261–276.

Arnett, J. J. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63, 602–614.

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Rode, J. C., Mooney, C. H., & Near, J. P. (2005). The subjective well-being construct: A test of its convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity. Social Indicators Research, 74, 445–476.

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319–325.

Brdar, I., & Kashdan, T. B. (2010). Character strengths and well-being in Croatia: An empirical investigation of structure and correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 151–154.

Brulde, B. (2007). Happiness and the good life: Introduction and conceptual framework. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 1–14.

Chan, D. W. (2010). Gratitude, gratitude intervention and subjective well-being among Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 139–153.

Chen, Y. P. (2004). The investigation of elementary school teachers’ well-being and its related factors. Ping Tung: National Ping Tung University of Education.

Chen, L. H., Chen, M.-Y., Kee, Y. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Validation of the gratitude questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Study, 10, 655–664.

Chuang, Y. C., & Lee, W. T. (2001). The structure of personality in Taiwanese children: An indigenous lexical approach to the big five model. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 43(1), 65–82.

Cohen, A. B. (2006). On gratitude. Social Justice Research, 19, 254–276.

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 9, 203–213.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Subjective emotional well-being. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 325–337). New York: Guilford.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 63–73). New York: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, L. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–426.

Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 130–141.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Duckworth, A. L., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629–651.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 56–69.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389.

Froh, J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examirüng gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 633–650.

Goldberg, J. R. (1990). An alternative “Description of Personality”: The big five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality-traits. American Psychologist, 48, 26–34.

Gordon, C. L., Arnette, R. A., & Smith, R. E. (2011). Have you thanked your spouse today? Felt and expressed gratitude among married couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 339–343.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Greenberg, M. S. (1980). A theory of indebtedness. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 3–26). New York: Plenum Press.

Harpman, E. J. (2004). Gratitude in the history of ideas. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 19–36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Heine, S. J., & Buchtel, E. E. (2009). Personality: The universal and the culturally specific. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 369–394.

Hill, P. L., & Allemand, M. (2011). Gratitude, forgivingness, and well-being in adulthood: Tests of moderation and incremental prediction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(5), 397–407.

Hunsley, J., & Meyer, G. J. (2003). The incremental validity of psychological testing and assessment: Conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues. Psychological Assessment, 15, 446–455.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Karlson, C. W., Gallagher, M. W., Olson, C. A., & Hamilton, N. A. (2013). Insomnia symptoms and well-being: Longitudinal follow-up. Health Psychology, 32(3), 311–319.

Kashdan, T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77(3), 691–730.

Kee, Y. H., Chen, L. H., & Tsai, Y. M. (2008). Relationships between being traditional and sense of gratitude among Taiwanese high school athletes. Psychological Reports, 102, 920–926.

Lin, C. C., & Yeh, Y. C. (2011). The development of the “Inventory of Undergraduates’ Gratitude”. Psychological Testing, 58(S), 2–33.

Linley, P. A., & Harrington, S. (2006). Playing to your strengths. The Psychologist, 19, 86–89.

Linley, A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., Peterson, C., et al. (2007). Character strengths in the United Kingdom: The VIA inventory of strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 341–351.

Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., & Hooe, E. S. (2003). Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: Evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 465–481.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of subjective well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 616–628.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131.

Martínez-Martí, M. L., Avia, M. D., & Hernández-Lloreda, M. J. (2010). The effects of counting blessings on subjective well-being: A gratitude intervention in a Spanish sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 886–896.

McAdams, D. P., & Bauer, J. J. (2004). Gratitude in modern life: Its manifestations and development. In R. A. Emmons & M. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 81–99). New York: Oxford University Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1999). A five-factor theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. E. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 139–154). New York: Guilford Press.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Classical sources of human strength: Revisiting an old home and building a new one. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 1–10.

McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J.-A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 295–309.

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. (2006). Applied multivariate research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nelson, C. (2009). Appreciating gratitude: Can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being? Counselling Psychology Review, 24(3–4), 38–50.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and wellbeing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603–619.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172.

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 149–156.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 627–639.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it—Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Positive psychology: Fundamental assumptions. The Psychologist, 16, 126–127.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Sheldon, K. M., & King, L. (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist, 56(3), 216–217.

Shimai, S., Otake, K., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Convergence of character strengths in American and Japanese young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 311–322.

Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2007). Positive psychology: The science and practical explorations of human strengths. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161.

Toussaint, L., & Friedman, P. (2009). Forgiveness, gratitude, and well-being: The mediating role of affect and beliefs. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 635–654.

Tsang, J.-A. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behaviour: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion, 20, 138–148.

Veisson, M. (1999). Depression symptoms and emotional states in parents of disabled and non-disabled children. Social Behavior and Personality, 27, 87–98.

Watkins, P. C. (2004). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 167–194). New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31, 431–452.

Weiner, B., Russell, D., & Lerman, D. (1979). Cognition–emotion process in achievement-related contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1211–1220.

Whatley, M. A., Webster, J. M., Smith, R. H., & Rhodes, A. (1999). The effect of a favor on public and private compliance: How internalized is the norm of reciprocity? Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21, 251–259.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 890–905.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 1108–1125.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Lloyd, J., & Atkins, S. (2009a). Gratitude influences sleep through the mechanism of pre-sleep cognitions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66, 43–48.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2008a). Gratitude uniquely predicts satisfaction with life: Incremental validity above the domains and facets of the five factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 49–54.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009b). Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the big five facets. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 443–447.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 15–19.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008b). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 854–871.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Stewart, N., & Joseph, S. (2008c). Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 619–630.

Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Positive clinical psychology: A new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 819–829.

Zhao, Y. (2012). Gratitude aud indebtedness: Exploring their relationships at dispositional and situational levels among Chinese young adolescents in Hong Kong. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 73(3-B), 1900.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CC. A higher-Order Gratitude Uniquely Predicts Subjective Well-Being: Incremental Validity Above the Personality and a Single Gratitude. Soc Indic Res 119, 909–924 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0518-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0518-1