Abstract

In this review, I use Emmons and McCullough's excellent volume on gratitude as a platform for discussing several issues in emotion, cultural, and moral psychology. First I summarize this exceptionally rich edited book, which provides accessible reviews of the philosophy, theology, anthropology, sociology, evolutionary biology, and psychology of gratitude. I next take up four questions inspired by the book. First, I consider whether gratitude is an emotion, and how to operationally define emotions. Second, I discuss the cognitive components of gratitude, including the appraisal structure of gratitude and whether gratitude can occur without an attribution. Third, I take up the question of whether gratitude is indeed a positive emotion, and propose some complications in the nature of positive emotions. Last, I consider potential sources of individual, cultural, and religious differences in gratitude, such as whether gratitude is mostly about internal feelings or the fulfillment of social obligations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psychology has typically viewed emotions as internal experiences that were selected for because they enhance the fitness of the individual experiencing them. But more recently, psychology has come to realize the importance of emotions that orient our concerns away from our own, narrow interests to the interests of others. While these emotions are no doubt also relevant to the individual’s fitness, they can also be seen more broadly and in a more social, moral, and self-transcendent context. It is probably a confluence of several factors that promoted this broadening of interest (Emmons, 2004). This change is also due in no small part to the efforts of Robert Emmons and Michael McCullough (2004), whose exemplary work on forgiveness and gratitude has demonstrated the relevance of these topics – and importantly that these topics are amenable to study using the most rigorous, multidisciplinary methods. In this context, I am pleased to provide some comments about their edited book Psychology of Gratitude. First I will provide a summary of the book, which consists of chapters from an astonishing array of scholars from different fields. After providing these summaries, I will discuss how these chapters and other work on gratitude address four interrelated questions: Is gratitude an emotion? What are the cognitive components of gratitude? Is gratitude positive or negative? And is gratitude moral?

Summary

Forward and Introduction

In his forward, philosopher Robert Solomon points out that gratitude is both one of the most neglected emotions, but also one of our most important virtues, and indeed it may be at the core of other virtues. Solomon wonders why gratitude is so neglected. One reason, as Hume pointed out, is that it is a calm passion, not ‘‘violent’’. It may also be the case that gratitude makes us uncomfortable because of its link to indebtedness. Gratitude’s link to indebtedness, and the fact that it might thereby feel both positive and negative, is an issue that arises often in the book.

From an emotion perspective, Solomon claims that gratitude is unlikely to be a basic emotion, given that it has not been shown to have a physiological profile or a hardwired behavioral response, and that it cannot be traced or reduced to a particular neurological process. Unlike basic emotions, Solomon claims, gratitude is not usually expressed through a hardwired (and perhaps culturally invariant) facial display, but is usually expressed by thanks, an appreciative silence, and a return gift. Also, Solomon interestingly proposes that, unlike basic emotions, gratitude can be seen as appropriate or inappropriate (in that it should be sincere).

Another fundamental issue Solomon introduces is whether gratitude has to be directed at a person, or whether it can be directed at something impersonal, such as the cosmos. Partly because of this question, Solomon settled on a definition of gratitude as seeing the bigger picture. In this view, being grateful for one’s life does not mean being grateful toward an individual or God, but in being aware of one’s whole life. This interesting question of the object of gratitude and its cognitive components is also something that many authors considered carefully, and is a theme to which I will return below.

In his introduction, Emmons notes that gratitude has been almost totally neglected in the emotion literature. He suggests that time is ripe for studying it because of a number of developments in recent years, including an increased interest in what is positive and virtuous (Peterson and Seligman, 2004), greater interest in religion and spirituality (Hill and Pargament, 2003), and perhaps other factors.

Part 1: Philosophical and Theological Foundations

The first major section of the book concerns philosophical and theological foundations of the study of gratitude. In the first chapter, Edward Harpham (2004) provides a far-reaching and fascinating review of treatments of gratitude in philosophy. The Roman stoic philosopher Seneca posed fundamental definitional questions about gratitude, such as what it means for a gift to be properly given. The intentions of the giver and receiver were key in this formulation in that Seneca claimed gratitude arises from a gift freely given, not when the gift was obligated or part of a commercial exchange.

In other classic works, Hobbes said that gratitude was necessary in society to ensure that people, who he saw as naturally self-interested, will do things for others and society. The German philosopher Pufendorf considered gratitude as based on relationship between people. In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, (Adam Smith, 1976/1790) argued that even if humans are driven essentially by self-interest, we are also capable of love, compassion, gratitude—and that these emotions help commercial society. For Smith, gratitude is a passion or sentiment that motivates us to reward others for good things they have done for us. He addressed questions such as when people feel gratitude, when gratitude is proper, and how gratitude is channeled in socially beneficial ways. These remain questions for modern gratitude researchers.

In Chapter 3, Solomon Schimmel (2004) addresses gratitude in Judaism. Gratitude is valued in many religious traditions (Emmons and Crumpler, 2000). Samuels and Lester (1985) demonstrated that gratitude was one of the most commonly reported emotional experiences that Catholic nuns and priests experienced toward God (along with hope, friendliness, happiness, reverence, affection, delight, and enjoyment). Reiser (1932) interestingly proposed that gratitude toward the sun for its benefits provided a ‘‘primitive’’ basis for religion. Gratitude does seem to be a common part of relationship to God or other religious experiences (reviewed in McCullough et al., 2001).

Schimmel explains that, in Judaism, gratitude both to God and to certain other people is emphasized, and indeed, obligated. This raises several issues of interest—first, that a religious tradition can be focused not only on gratitude to God, but also to other people, such as parents and teachers. Second, the notion of gratitude being obligated may seem paradoxical. But Schimmel explains that in Judaism, gratitude may even be obligated for actions that had good consequences indirectly or without intention (such as whether Jews should feel gratitude for deriving benefits from Persian or Roman occupation).Footnote 1

In Chapter 4, philosopher Robert Roberts suggests that gratitude intuitively seems to belong with happiness and well-being (as positive) and not with anger or anxiety (negative emotions). And data from Park et al. (2004) as well as McCullough et al. (2004) do strongly suggest links between life satisfaction and gratitude. But Roberts carefully considers this issue on conceptual (rather than empirical) grounds and notes that gratitude is not necessarily virtuous and positive. Of importance, Aristotle (1962) did not list gratitude as a virtue because Aristotle noted that gratitude puts one in an inferior position, and thus is incompatible with magnanimity.

We might or might not be inclined to disqualify gratitude as a virtue simply because Aristotle did, but I was quite struck by how often in the book the issue of gratitude, status, and indebtedness arose. Clearly this is still a salient and relevant issue. Roberts thus carefully discusses what gratitude is, and lays out a precise model of it as a three-term construal in which a subject construes herself as the recipient of some good from a beneficiary. This model is consistent with early theorizing by Tesser, who talked about gratitude in terms of the intention of the benefactor, cost to the benefactor, and value of the benefit (Tesser et al., 1968). In addition, the received good must be construed in terms of certain intentions—if the received good is seen as obligatory, or done out of malice, gratitude will not emerge. In this model, Roberts highlights the need for gratitude to be directed at someone, given certain intentions. This emphasis on social interaction and intentions is interesting in light of another issue that came up repeatedly in this book and in other treatments of gratitude (e.g. Peterson and Seligman, 2004): Whether gratitude can be felt in the absence of an attribution or indeed can be directed at something impersonal (such as luck or the cosmos in general). Roberts concludes by arguing that gratitude is a virtue and blessing in part because it is incompatible with resentment, regret, and envy.

Part II: Social, Personality, and Developmental Approaches to Gratitude

In the first chapter of Part II, Dan McAdams and Jack Bauer (2004) argue that the relative absence of gratitude in modern life might suggest that gratitude is not necessary for autonomy, achievement, and self-actualization. But McAdams and Bauer claim that gratitude is a crucial theme in the Bible, and that the fall of Adam and Eve can be seen as the result of a lack of gratitude. The authors also point out the importance of sacrifice in the Old Testament (or Hebrew Bible), suggesting that sacrifices be seen fundamentally to be about gratitude.Footnote 2 They also suggest that Judas’ betrayal of Jesus can be seen to reflect lack of gratitude.

Somewhat as they have traced gratitude throughout the Bible, McAdams and Bauer provide a compelling developmental approach using gratitude as a guiding theme. Assuming gratitude requires the attribution of agency to another person, McAdams and Bauer expect that gratitude in its full form could only emerge at around age 4, when children begin to have a theory of mind. Thus, gratitude in adolescence may develop in more complex ways as self-understanding becomes richer. Their study of adults’ reports of life transitions suggests that, though it is correlated with well-being, gratitude is rarely reported in connection with career. In religion, gratitude seems to be more common. In middle life, the developmental task of generativity may be girded by gratitude: Generative adults tell their life stories in terms of what these authors call a commitment story, involving a narrative of early advantage, understanding the suffering of others, being morally steadfast, undergoing redemption sequences, and prosocial goals. The authors claim “The very concept of generativity, moreover, can be seen as an outgrowth of gratitude. Many highly generative adults will remark that...it is time in their lives to give something back, to nurture and take care of the world, for others have been good enough to do that for them” (p. 95). Into older adulthood, as well, having ego integrity can be central to feeling life was worth living and good, and to being grateful.

Ross Buck’s Chapter 5 contains many interesting and novel ideas. In perhaps the most novel and far-reaching distinction, Buck distinguishes between a gratitude of exchange and a gratitude of caring. In a gratitude of exchange, the low power person experiences gratitude when she has received something valuable from a more powerful benefactor. These are often zero sum situations. But in a gratitude of caring, the exchange process is based on interdependence and mutual benefit, and this is not a zero sum scenario. Buck even supposes that in a gratitude of caring, the more you give, the more you get, and hence this does not entail one person being subordinate to another. Buck also acknowledges the dark side of gratitude, when we feel gratitude for another’s suffering or subjugation (as in schadenfreude). This raises deep questions about the positive nature of gratitude, which I will return to below.

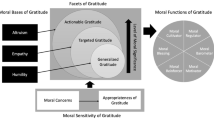

The last chapter of Part II is Michael McCullough and Jo-Ann Tsang’s ‘‘Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude.’’ In an earlier article on the moral nature of gratitude, McCullough et al. (2001) offered a theoretical framework for understanding the many moral aspects to gratitude. They included the idea that gratitude serves a ‘‘moral barometer’’ function, a ‘‘moral motive’’ function, and a ‘‘moral reinforcer’’ function. Gratitude serves as a moral barometer in that “gratitude is dependent on social cognitive input... we posit that people are most likely to feel grateful when (a) they have received a particularly valuable benefit; (b) high effort and cost have been expended on their behalf; (c) the expenditure of effort on their behalf seems to have been intentional rather than accidental; and (d) the expenditure of effort on their behalf was gratuitous (i.e., was not determined by the existence of a role-based relationship between benefactor and beneficiary)’’ (McCullough et al., 2001, p. 252). Importantly, they distinguish in this context between local morality and absolute morality, pointing out that people can be grateful for some benefit that is immoral from an outside, objective, or absolute perspective. Gratitude is a moral motive because it motivates the recipient to reciprocate, thus encouraging moral behavior. Gratitude also acts as a moral reinforcer in that it encourages the benefactor to behave morally again. Furthermore, of some relevance to its moral status, gratitude is associated with a positive pattern of personality—such as high agreeableness and low narcissism.

McCullough and colleagues clearly provide a sophisticated theoretical framework. To me, the most interesting question to emerge from it is the question of why people report gratitude when no agent is seen as responsible for their good fortune. There are three possible explanations according to McCullough and Tsang. Perhaps people are inclined to attribute their benefit to some kind of agent, even if this agent is luck, fate, or the cosmos. Another possibility is that people are not actually feeling gratitude, but mislabel other positive emotions (such as happiness) as gratitude. A third hypothesis is that other emotions that do not depend on attributions do indeed promote gratitude.

Part III: Perspectives from Emotion Theory

Part III of the book concerns ‘‘Perspectives from emotion theory.’’ Fredrickson’s chapter relies on her prior thinking on how positive emotions broaden and build cognitive flexibility and social resources (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001). Here, she argues that gratitude, too, broadens and builds—and not in a narrow way, but encourages us to think broadly of creative ways to reciprocate or reflect gratitude. She also proposes that gratitude might build social resources via its role in reciprocal altruism (which Bonnie and de Waal discuss extensively in Chapter 11). Gratitude can also motivate faithfulness and interdependence in relationships.

Fredrickson reviews her impressive work showing that positive emotions help people deal with stress and negative emotions, and speculates that gratitude may serve these functions as well. Fredrickson and Joiner (2002) showed that positive, but not negative, affect improved broad-minded coping, and that initial broad-minded coping increased positive affect, but did not reduce negative affect. Fredrickson and Levenson (1998) showed that positive emotions helped subjects return to pre-film levels of cardiovascular functions after viewing a fear-inducing film clip, relative to those who saw neutral or sad films. Moreover, those who spontaneously smiled during a sad film clip returned more rapidly to pre-film cardiovascular function.

Fredrickson suggests several interesting questions to which future work should be addressed: Does gratitude broaden and build as do other positive emotions? Does gratitude build positive relationships, societies, and organizations? Does gratitude lead to health and well-being? Does it explain relationships between religion or spirituality and health? Of relevance to issues involving the link between gratitude and indebtedness and the question of why gratitude is a positive emotion, Fredrickson predicts that gratitude would lead to broad, creative ways to repay a debt, but that indebtedness (which she assumes is aversive) would lead to straightforward, narrow, tit-for-tat repaying.

Watkins’ (2004) tasks in the next chapter are to review research on the relationship between subjective well-being and gratitude, and to review the small number of studies that have manipulated gratitude and subjective well-being. He then proposes mechanisms to account for the relationships, and provides suggestions for future directions. Watkins notes that gratitude is a better predictor of several different measures of subjective well-being than demographic factors; the sizes of these relationships are equal to, or larger than, relationships of subjective well-being with neuroticism or sociability. One of his own studies shows that grateful people have more positive memories than negative ones and are also likely to have positive intrusive memories (Watkins et al., 2004). This is a particularly important set of findings because it goes beyond simply correlating self-reports of gratitude with self-reports of subjective well-being. Other non-self-report studies also provide similar conclusions, such as when using peer-reports (e.g. McCullough et al., 2002). Clearly one of the most impressive non-self-report studies on gratitude and subject well-being is work by Emmons and McCullough (2003) showing that experimentally manipulating gratitude promotes positive emotions and general affect. Another study, of the diaries of nuns in early life, showed that high positive emotionality (including gratitude) powerfully predicted a greater life span (Danner et al., 2001).

In addition, Watkins claims that gratitude is likely to be reciprocally related to subjective well-being via several theorized mechanisms: by promoting other positive emotions that contribute to subjective well-being, by counteracting habituation, by decreasing upward social comparisons, by increasing ability to delay gratification, by serving as a coping mechanism, by increasing accessibility of positive life events, by increasing actual benefits, or by decreasing depression. Watkins recommends that future work rely less on self-reports, employ cognitive measures, and seek to demonstrate how gratitude can be induced in the laboratory.

Part IV: Perspectives from Anthropology and Biology

Part IV provides insights from broader cultural and biological perspectives. Aafke Elisabeth Komter’s (2004) Chapter 10 draws on sociological, psychodynamic, and anthropological perspectives. Data she presents on cultural variability provide a set of cultural principles to address issues raised elsewhere in the volume, including the relationship of gratitude to indebtedness. Reviewing anthropological work on the relationships among gift, exchange, and gratitude, she discusses ceremonial gift exchange among Trobriand islanders as well as cycles of gift giving among the Maori. In each case, the cultural meaning of gift giving is heavily bound up in notions of cycles. She explores how the foundation for trust, hope, and belief in goodness is laid for a child in the experience of breastfeeding, and how being deprived in this sense can lay the foundation for envy.

Her own study of gift giving in the Netherlands demonstrates how gratitude promotes reciprocity in communal life. She found that women, younger people, and better educated people were more likely to give gifts, and that notions of reciprocity were frequent motivators of gift giving, both for material and non-material gifts. Of interest, people often had the sense that they give more than they receive. She summarizes her findings by suggesting how issues of power and interdependence are integral to gratitude. She argues that each of four ‘‘manifestations’’ of gratitude (e.g., ‘‘joy and the capacity to receive’’ and ‘‘webs of feelings connecting people’’) are linked to one of four “layers” of gratitude (respectively ‘‘moral/psychological” and “societal/cultural’’).

The potential role of gratitude in reciprocal altruism is raised in many chapters, but it is the centerpiece of Bonnie and de Waal’s Chapter 11 (“Primate social reciprocity and the origin of gratitude”). Bonnie and de Waal (2004) argue that the ubiquity of gratitude across cultures reflects a biological predisposition, of which we can see hints in other animal species. (Adam Smith even thought that animals could experience something like gratitude; Smith saw the ability to appreciate gratitude as a spectrum, with animals between inanimate objects and humans in this regard.)

Bonnie and de Waal acknowledge the difficulty in distinguishing gratitude from pleasure in animals. There is a striking amount of cooperation among individuals in nature, and in the special case of reciprocal altruism, such cooperation relies on fairly sophisticated memory of who helped, at what cost, and which others are likely to be cheaters versus reciprocators (Trivers, 1971). Gratitude could, in certain species, contribute to such exchanges, and the need for gratitude would be greater in species with highly complex and cooperative societies. Bonnie and de Waal recognize that gratitude cannot be inferred simply from the presence of cooperation, because there are other accounts. They thus consider carefully whether gratitude could explain cooperative (such as food sharing) behaviors in species as diverse as vampire bats, capuchins, and chimpanzees.

In this context, Bonnie and de Waal distinguish different mechanisms of reciprocity, including symmetry-based and calculated. In symmetry-based reciprocity, close individuals help each other without stipulating returns. In calculated reciprocity, the continuation of helpful behavior depends on reciprocation. Vampire bats, who share blood with each other, may simply rely on symmetric reciprocity, with closely related kin sharing blood. On the other hand, capuchins’ food sharing is not completely accounted for by the simpler symmetric reciprocity, but may share features of calculated reciprocity.

However, chimpanzees may show gratitude very much akin to the human experience. Regarding the food and grooming reciprocity observed among chimps, Bonnie and de Waal argue that ‘‘if chimpanzees indeed feel good about benefactors, remember them, and have a tendency to repay favors received, it will be hard not to count the mechanism of gratitude among the possibilities’’ (p. 223). Given a close phylogenetic relation between humans and chimps, these authors consider it reasonable to assume the same mechanism is involved in chimps and humans. Bonnie and de Waal consider that because morality cannot exist without reciprocity, one could consider the presence of gratitude in certain primates to suggest the presence of morality. They also point out that if reciprocal altruism depends on gratitude, there must also be a mechanism to punish defectors (cheaters), and chimpanzees do punish individuals who do not hold up their responsibilities. This suggests that punishment and retribution may be as important to cooperation as gratitude is.

In Chapter 12, Rollin McCraty and Doc Childre examine biological features of the experience of appreciation. Though it has some overlap with gratitude, the authors claim that appreciations does not have to be directed at another person, as they feel gratitude does—and so appreciation may not carry with it the sense of obligation and indebtedness that gratitude can. Based on their work on the physiology of appreciation, the authors claim that appreciation promotes ‘‘coherent’’ and related types of improved physiological function. Changing feeling from frustration to appreciation, they say, makes the heart rhythm smooth and harmonious, which they claim is coherent. Furthermore, they claim appreciation and other positive states promote cross-coherence (when two or more systems, such as heart and respiration, covary). They suggest these kinds of coherence increase cognitive abilities, stress management, physical health, well-being, and positive emotions.

Part V: Discussion and Conclusions

Charles Shelton’s Chapter 13 synthesizes and adds to many prior discussions. He points out that to claim that a capacity to feel gratitude is an indicator of moral worth is problematic. For example, Shelton argues, Hitler after all probably did at times feel gratitude. And we can recall McCullough and Tsang’s distinction between local and absolute morality in this context, as well as related arguments by Roberts, and Buck, and others. As such, Shelton provides an in-depth consideration of the relation of morality to gratitude and conceptions of the good and comes to propose that ‘‘the deepest form of gratitude is viewed as a way of life that is best defined as an interior depth we experience, which orients us to an acknowledged dependence, out of which flows a profound sense of being gifted. This way of being, in turn, elicits a humility, just as it nourishes our goodness. As a consequence, when truly grateful, we are led to experience and interpret life situations in ways that call forth from us an openness to and engagement with the world through purposeful actions, to share and increase the very good we have received’’ (p. 273, italics in original).

David Steindl-Rast’s final, and unfortunately quite short, chapter attempts to add some linguistic and psychological precision to the notion of gratitude. He proposes a series of theses, which he claims has weighty implications for the science and study of gratitude. First he claims that gratitude is essentially a celebration, by which he means ‘‘an act of heightened and focused intellectual and emotional appreciation’’ (p. 283). In his second thesis, he sharpens this proposition by claiming that gratitude is a celebration of undeserved kindness (emphasis mine). Third, he distinguishes personal from transpersonal gratitude. In the former, we are grateful in the context of a specific instance. The latter is more universal, unreflective, and unconditional. His fourth thesis is that gratefulness and thankfulness are distinct and that thankfulness goes more with personal gratitude, but gratefulness with transpersonal gratitude. His fifth thesis is that gratitude is highly relevant to spiritual, religious, and mystical experiences, as well as peak experiences (Maslow, 1964).

Last in the book is an appendix by Jo-Ann Tsang and Michael McCullough (2004) that has an annotated bibliography of some 35 studies, descriptive and experimental. This is particularly helpful because for each study, they give an overview of the objective, design, manipulated variables, outcome variables, results, and conclusions, as well as a short commentary about the main thrust, limitations, or advantages of each study.

Abiding questions and issues

This volume provides a set of very rich and helpful treatments of various aspects of gratitude, ranging from anthropology to zoology, though perhaps most often focusing on the psychological and philosophical. Despite the range of perspectives and a substantial amount of agreement among theorists, there are also a number of important issues that are controversial, unresolved, or at least could use some further refinement. The interrelated questions I wish to turn to next are: Is gratitude an emotion? What are the cognitive components of gratitude? Is gratitude a positive emotion? Is gratitude a moral emotion?

I propose that answers to none of these questions are obvious, not least because of the wide variety of definitions of gratitude in the literature. Emmons (2004) defines gratitude as ‘‘...an emotion, the core of which is pleasant feelings about the benefit received...gratitude is other-directed—its objects include persons, as well as non-human intentional agents (Gods, animals, the cosmos...)...’’ (p. 5). And this definition is similar to that of Peterson and Seligman (2004): ‘‘Gratitude is a sense of thankfulness and joy in response to receiving a gift, whether the gift be a tangible benefit from a specific other or a moment of peaceful bliss evoked by natural beauty...Prototypically, gratitude stems from the perception that one has benefited due to the actions of another person’’ (p. 554). And similarly, early on, Baumgarten-Tramer (1938) proposed that gratitude has four components: gladness, benevolence toward the benefactor, a desire to reciprocate, and a feeling of obligation to reciprocate. However, other definitions depart in important ways from these views. For Solomon (2004), gratitude essentially consists of seeing the bigger picture. For Steindl-Rast (2004), gratitude is essentially a celebration.

Gratitude as an Emotion

Gratitude theorists in the current volume, as well as others, seem to agree that gratitude is an emotion (e.g. Peterson and Seligman, 2004). Of interest, Solomon (2004) proposes gratitude probably is not a basic emotion because he presumes it does not have a biologically ingrained behavioral display, neurological process, or physiology, seen as the hallmark of a basic emotion. Izard (p. 562) claims basic emotions are the basis for coping and adaptation. Further, ‘‘Particular emotions are also called basic because they are assumed to have innate neural substrates, a unique and universally recognized facial expression, and a unique feeling state’’ (p. 562). It should be stressed that the concept of basic emotions is still hotly contested (Ekman, 1992; Izard, 1992; Ortony and Turner, 1990; Panksepp, 1992; Solomon, 2002; Turner and Ortony, 1992; cf. Ekman and Davidson, 1994).

At times, it seems that the emotion literature has been so occupied with debating whether there are basic emotions and what they might be that there has been less guidance about how to decide whether something is an emotion at all (Rozin and Cohen, 2003b). Recently, Keltner and Shiota have offered the following definition: ‘‘An emotion is a universal, functional reaction to an external stimulus event, temporarily integrating physiological, cognitive, phenomenological, and behavioral channels to facilitate a fitness-enhancing, environment-shaping response to the current situation’’ (Keltner and Shiota, 2003, p. 89, italics in original). A discussion of the status of gratitude as an emotion or basic emotion points to many issues, such as whether gratitude might have an identifiable behavioral display, what its physiology may be like, whether it is affectively or phenomenologically positive or negative, and what its cognitive components are.

Emotion psychologists have tended to use expressive facial behavior as the gold standard in emotion research, and because of Ekman’s influential theorizing about basic emotions, certain emotion facial displays have been well-characterized, but others have not (Rozin and Cohen, 2003a, b). Is the facial behavior of gratitude distinct from that of other emotions? Perhaps several positive emotions blend together and are not distinguishable in facial behavior. In fact, several of the current authors (as well as others) point to some conceptual overlap between gratitude and other positive emotions. For example, Solomon characterized gratitude as a positive counterpart to vengeance. To me, this suggests some similarity between gratitude and forgiveness. Peterson and Seligman (2004) wonder whether gratitude can be experienced in response to natural beauty but in the absence of an attribution (to God or the cosmos) about the source of the natural beauty, or whether it was intended to benefit the individual experiencing the beauty. This suggests some similarity between awe, or pleasure, and gratitude.

To the extent that gratitude is experienced as a positive emotion, as most theorists agree, it seems plausible that the facial display would bear some similarity to that of happiness. If this is the case, it could raise a number of interesting research questions. It has long been known that sincere happiness is expressed differently on the face from feigned happiness. While both involve a raising of the lip corners, only sincere happiness (evident in a Duchenne smile) also involves the contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscles, which raises the cheek, creates crow’s feet, and bags under the eyes. Harker and Keltner (2001) coded for the presence of Duchenne smiles in the college yearbook photos of a sample of women from Mills College, and correlated the presence of sincere positive emotion on the face to life outcomes decades later. They found that those women who showed more sincere positive emotion on the face had better life outcomes, such as more successful marriages and more positive emotion. A similar strategy could perhaps be used to distinguish sincere from less sincere gratitude behaviors. Similar arguments could no doubt be made about the physiology of gratitude, and we already have some interesting suggestions regarding appreciation and physiological coherence (McCraty and Childre, 2004).

I would like to suggest one additional candidate for the physiology of gratitude, increased respiratory sinus arrhythmia, or increased vagal tone. When we inhale, our heart rate increases, and when we exhale, our heart rate decreases, in a pattern called respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). RSA is heavily influenced by vagus nerve activity, or vagal tone. Porges (1992) theorized that greater RSA indicates a greater ability both to respond to stressful stimuli, and, importantly, to recover from that stress. In a converging analysis, Haidt (2003) has theorized that the physical sensations (such as an opening up feeling in the chest) we get when we observe a virtuous act can be traced to changes in vagus activity.

Evidence is beginning to emerge that RSA is associated with positive emotionality and personality profiles. Dacher Keltner, Christopher Oveis, and I (2005) recently had subjects come into the lab, where we obtained a baseline measure of RSA. Months later, participants filled out an extensive battery of personality measures, such as the Big Five Inventory (John et al., 1991), and Scheir and Carver’s (1985) life orientation test. People with high RSA had significantly higher self-reported extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness on the Big Five Inventory, as well as lower neuroticism. They also had higher trait optimism and lower pessimism. We theorize that RSA may be a physiological marker of resilience and social engagement which is correlated with a variety of positive personality and emotion outcomes (Oveis et al., 2005). Gratitude seems likely to fit into this framework.

Gratitude as a Distinct Positive Emotion

An alternative theoretical perspective is that positive emotions (such as awe, compassion, forgiveness, pride, etc.) are quite distinct and that they have different facial displays, physiological patterns, etc. Why is it that it is so difficult to distinguish gratitude from other positive emotions? Perhaps part of the explanation is that emotion taxonomies tend to be heavily weighted toward negative emotions, and it is only within the last decade that some very promising developments have begun to speak to positive emotions (Fredrickson, 1998, Fredrickson et al., 2003; Shiota et al., 2004). This may be because an influential theoretical tradition in emotion psychology proposed that emotions have specific action tendencies that enhance fitness. In the case of disgust, the action tendency is to expel a noxious substance from our bodies, which may help us avoid toxins. Fear helps us flee. Anger helps us attack.

Fredrickson noted that the action tendencies associated with positive emotions are not as obvious. For example, how does experiencing contentment contribute to fitness? Fredrickson significantly advanced the study of positive emotion (such as joy, contentment, interest, and love) by claiming that positive emotions broaden mental, psychological, and social resources, expand behavioral repertoires, and fuel psychological resiliency. While emotions such as joy, contentment, interest, and love may be experientially distinct, Fredrickson claims that they all broaden and build—and that gratitude, may as well (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001, 2004).

Moreover, recent work has pointed to differences among positive emotions. Shiota et al. (2004) discuss the functions of positive emotions in interpersonal relationships, and identify three functions: positive emotions provide information, they evoke emotional responses in others, and they provide incentives for others’ behavior. Importantly, in this discussion, Shiota et al., clearly distinguish between joy, love, desire, compassion, gratitude, pride, amusement, awe, and interest, outlining the different functions of each in different types of relationships (such as parent–child, romantic partners, etc.). Distinct positive emotions may even have distinct facial displays, and there is evidence for prototypical and distinct displays for awe, amusement, and pride (Shiota et al., 2003; cf. Tracy and Robins, 2004, for pride).

Such theorizing could present significant future directions to gratitude researchers in providing them specific tools to measure gratitude as distinct from other positive emotions. Although there are already several individual difference measures of gratitude (e.g. McCullough et al., 2002), it seems it would be fruitful to measure several distinct positive emotions to show that effects are due to gratitude in particular and not to other, perhaps related, positive emotions.

Cognitive Components of Gratitude

In the context of using the emotion literature for inspiration while discussing the properties of gratitude, another important consideration would be the cognitive components of gratitude, such as the role of attributions in gratitude. In the emotion literature, a similar idea has to do with ‘‘appraisals’’ and there is a tradition of investigating the appraisal structure of positive emotions (e.g., Roseman, 1991; Smith and Ellsworth, 1985), such as for love in romantic relationships (Fitness and Fletcher, 1993) and interest (Silvia, 2005). It has been quite persuasively argued that appraisal processes powerfully determine which emotion is experienced in a given situation (Roseman, 1991, 2004). If this is so, then distinct appraisal patterns could result in gratitude versus another positive emotion, such as elation or awe. Nevertheless, the role of cognition in emotion is controversial; to a large extent, this debate revolves around how cognition is defined in relation to emotional processing (Davidson and Ekman, 1994).

The appraisal structure or attributions of gratitude are currently quite controversial. For example, Peterson and Seligman (2004) consider whether we can experience gratitude in the presence of great beauty without attributions. McCullough and Tsang (2004) discuss possible reasons why people report gratitude in the absence of an attribution of their success or good outcome to an outside agent; these authors considered whether people are determined to attribute their benefit to some agent, or whether people mislabel other positive emotions as gratitude, or whether other emotions promote gratitude.

Given the prior discussion on the confusion about discrete positive emotions, I suggest that we—theorists, researchers, and study participants—do not have the sophisticated taxonomy that we need to say what positive emotion we are really feeling. It seems to me a compelling theoretical argument, from Seneca and through work by Weiner and others, that gratitude, by definition, needs an attribution (Weiner, 1985; Weiner et al., 1978, 1979; cf. Graham and Barker, 1990; Graham et al., 1992). Even if we label our emotional experience as gratitude, I suggest that, without attributions to an agent, seeing the Grand Canyon makes us feel awe, winning the lottery makes us feel elation, and forgoing vengeance makes us forgiving or forbearing—but not grateful. I believe that such definitional clarification could open up many lines of research into the cognitive appraisals and attributions that distinguish gratitude from other positive emotions.

What is Positive about Gratitude? Are There Cultural and Individual Differences?

Theorists in the current volume and elsewhere seem unanimously to place gratitude in the category of positive emotions, at the same time as several caution against viewing it exclusively positively (e.g. Buck, 2004; Shelton, 2004). Is gratitude in fact a positive emotion? Why might it be, and why might it not be? I suggest that there are several distinct ways in which gratitude (or many other emotions) could be good or bad.

Perhaps gratitude is positive to the extent that it feels good to experience gratitude. When Roberts (2004) began his conceptual analysis of the blessings of gratitude, he allowed that the intuitions of many of us put gratitude with happiness and well-being, and away from anger, anxiety, envy, or schadenfreude. Perhaps it is positive because gratitude is inversely associated with negative states, such as envy or materialism (McCullough et al., 2002).

Probably gratitude is indeed, usually, hedonically positive. But not always, at least in my experience. When I contemplate the things I am most grateful for in life (as writing this essay has prompted me to do in some depth), near the top of my list would be that I feel grateful for my love of learning. I have been blessed throughout my life with role models, such as my parents, other family members, teachers, and mentors, who have nurtured this in me, and I feel grateful them for this. But when I consider this gratitude, it does not feel exclusively good to me. Along with the positive feelings, I also often feel a sense of guilt that derives from my feeling that I did nothing special to deserve this treatment, as well as guilt about not having done enough with these blessings. Given how my academic career has been buttressed by the mentorship I described, I feel there are cases in which I could have been a better mentor to others, and shown others the same compassion and support that I have received. This guilt-laden aspect of gratitude is hedonically negative for me, even as it might motivate me to behave morally in the future.

Perhaps I am especially neurotic, or over-analytical, and I am unique in my experiencing gratitude as a mix of positive and negative phenomenology. But I don’t think so. McDougall (1929) said gratitude is a blend of emotions including awe, admiration, reverence, envy, resentment, embarrassment, and jealousy, and called it a compound of ‘‘tender emotion and negative self-feeling’’ (p. 334). A second example is that disabled people, who rely more on others than do non-disabled people, may tend to see gratitude as a burden because it comes from constantly putting oneself in the debt of others and this can lead to feelings shame and frustration (Galvin, 2004).

In this vein, many authors have been impressed with Aristotle’s unwillingness to consider gratitude a virtue. For Aristotle, gratitude was closely linked to status, and gratitude was incompatible with being magnanimous: ‘‘The high-minded also seem to remember the good turns they have done, but not those they have received. For the recipient is inferior to the benefactor, whereas a high-minded man wishes to be superior’’ (Nicomachean Ethics, p. 97). If Aristotle is too far removed from modern culture to appreciate, the point that gratitude can be a burden was made eloquently in the masterful mystery novel Strong Poison by Dorothy Sayers (1930/1967). In this book, Ms. Harriet Vane is in on trial for murdering her live-in lover, and Sayers’ detective character, Lord Peter Wimsey, investigates and exonerates her. Despite a mutual admiration and attraction, she will not agree to marry him. It becomes clear over subsequent books in the series that she feels that the debt of gratitude she bears toward him will make their relationship hierarchical, rather than of equals. They do not marry until several books later, in Busman’s Honeymoon (Sayers, 1937/1995), when she feels the balance of power and obligation have finally been equalized.

Perhaps, then, a more appealing perspective is that gratitude is positive because it is a moral emotion. McCullough and colleagues (McCullough and Tsang, 2004; McCullough et al., 2001) have considered extensively the place of gratitude in moral psychology, proposing several moral aspects of gratitude (barometer, motivator, and reinforcer functions). It should be added that emotions can also serve as the basis of moral judgment (Haidt, 2001), and this fits nicely with McCullough and colleagues’ moral barometer function. Shelton (2004) also carefully considers whether we are really prepared to claim that experiencing gratitude is a measure of a moral person, when surely people such as Hitler could experience gratitude.

Whether gratitude is seen as moral, then, is a complicated issue. I do not know that I am equipped to solve the problem of the moral status of gratitude from a philosophical perspective. However, I do think that I can provide some possible directions about some ways in which individuals and cultures might vary in their views of gratitude, morality, and indebtedness. For cultural psychologist Richard Shweder, emotions ‘‘... are complex narrative structures that give shape and meaning to somatic and affective experiences...whose unity is to be found neither in strict logical criteria nor in the perceptible features of objects, but rather in the types of self-involving stories they make it possible for us to tell about our feelings’’ (Shweder, 1994, p. 37; cf. Shweder and Haidt, 2000). This definition alerts us to the fact that emotions are deeply embedded in cultural frameworks. What might be some of the dimensions of cultural and individual variability when it comes to gratitude?

First, it is likely individuals and cultures vary in how salient indebtedness is as an element of gratitude. As one example, in Japan, positive relationships are built on love, gratitude, friendship, and obligation (Yoshida et al., 1966). Certain cultural syndromes like collectivism and interdependence mean that people are enculturated to be keenly aware of their dependence on people in the in-group and their obligation to reciprocate (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995). Hence, for Japanese, aspects of reciprocity and obligation are closely tied to gratitude (Ide, 1998; Kotani, 2002; Naito et al., 2005). Doi’s (1973) classic work Anatomy of Dependence analyzes the crucial role that feeling helpless, dependent, and indebted to close others plays in Japanese society.

Thus, interdependence and indebtedness may be seen in a positive light in certain cultural frameworks, and as negative in others. Fredrickson (2004) speculates that (positive) gratitude might promote broadening of ideas about how to reciprocate, whereas (aversive) feelings of indebtedness might promote a narrower, tit-for-tat strategy of reciprocity. I propose that it may be Americans that are most uncomfortable with this feeling of indebtedness because of the value they place on their independence and self-reliance (Doi, 1973; Markus and Kitayama, 1991, Triandis, 1995).

An additional dimension of individual and cultural differences, I propose, is in views of the moral status of obligation, reciprocity and gratitude. McCullough and colleagues have claimed that gratitude serves several moral functions, and to add to this insight, I propose that individuals and cultures will have different views. Appadurai has alerted us to the fact that operationalizing gratitude is not always easy, particularly in a cross-cultural context. Appadurai (1985) presents a fascinating analysis of expressions of gratitude in Tamil culture. He shows that, in Tamil culture, it is hard to express gratitude verbally for several reasons. One is that gratitude is most expressed through return gifts, and that notions of gratitude are inextricably tied up in obligation and reciprocity. In addition, Tamil culture is very status-conscious. Because people of higher status have a responsibility to care for people of lower status, it becomes difficult to distinguish voluntary benevolent actions from socially prescribed benevolent actions. Does one feel gratitude for acts that are performed out of responsibility? Furthermore, being grateful to someone for a gift assumes that they are the source of it, but Appadurai was exposed to the idea by a Tamil cleric that one ought to see a beneficial act or gift as ultimately coming from the Lord. Thus, Appadurai explains, Tamils tread carefully in expressing gratitude. One way to deal with this is to express gratitude non-verbally, via a return gift, as well as by focusing on the gift, not the giver, in expressions of gratitude. Appadurai thus points out that there is latitude in how one carries out duty. Does one reciprocate a gift with the minimum necessary, or does one go beyond?

Appadurai highlights numerous important cultural dimensions, but I now wish to turn to his insight that gratitude can be seen as referring to an inner state, or to a behavior. This too, I will argue, is culturally influenced. As Appadurai put it, ‘‘...it may also be that our Western (and probably Christian) conception of ‘gratitude’ refers ultimately to some inner disposition of the actor, and thus when gratitude is at issue, we always have at hand some technique for assessing whether a beneficiary is really grateful or is simply going through the motions...’’ (pp. 243–244). In this vein, I will argue that religion is one source of important cultural variation in whether the moral aspect of gratitude is in the performance or the inner feelings.

Cultures, including religious cultures, may all value gratitude on some level, but they likely also differ in certain important aspects. I have already mentioned the possibility that Americans are uncomfortable with the aspect of gratitude that is related to indebtedness and obligation. This may be partly due to their value of autonomy and independence, but there may be other causes, as well. Americans strongly value intrinsic motivations for moral and religious behavior, discounting behavior that is due to social influence or feelings of obligation (Batson, 1998).

But not all cultures will discount actions that are motivated by social reasons or obligation. I have argued that it is a particularly American Protestant viewpoint that privileges internal, intrinsic motivations over social motivations or duty-based motivations (Cohen et al., 2005). And in empirical research, I have provided evidence that members of different religious groups place different values on different motivations for religious or moral behavior, and these differences could be expected to be evident in views of gratitude, as well. As two examples, I have argued that, for Jews, what is morally important is upholding one’s social obligations, and there is less attention than among Protestants to whether the behavior is “appropriately” motivated. In one study with Paul Rozin, I showed that Jews consider a child to honor his parents if he behaviorally acts appropriately toward them, regardless of whether he likes them internally. Jews agree that people cannot be expected to internally like their parents. Protestants, on the other hand, consider it hypocritical for a son to act as if he likes his parents when he does not internally, and agree that what is important is for a son to honor his parents in his heart as well as in his behavior (Cohen and Rozin, 2001). In another study, Jews were less concerned than Protestants were about a student who tutored another student partly to curry favor with the professor. For Protestants, this selfish motivation made the act less moral, but not for Jews. Jews cared more about the prosocial outcome of the act (Cohen and Rankin, 2004). In all, this bears on gratitude because it suggests that cultures vary in whether they may see the true test of gratitude as being in whether one upholds social obligations or in whether one’s behavior reflects one’s internal, grateful state.

Summary

Theory and science on gratitude have exploded in recent years, with Emmons and McCullough’s edited book representing a major advance. With contributors carefully considering gratitude from different fields, those interested in gratitude have an immensely useful resource to turn to for inspiration. Future research, I believe, would also benefit from additional attention to the status of gratitude as an emotion, as moral, and the ways in which individuals and groups may differ in various contours of gratitude.

Notes

This example is striking because it considers whether gratitude is obligated for the benefits derived from occupation by a hostile power. But to me it raises interesting questions about whether to feel grateful for actions that were not harmful in the broader sense, but were still not intended to have a particular benefit to a particular individual. For example, in writing this article, it became apparent to me that I feel a sense of gratitude to Emmons and McCullough for laying the groundwork for work on religion, spirituality, and moral emotions in psychology. Their germinal studies inspired me to do my own work, and also made it easier to do my work by making the field more receptive to such topics. But Emmons and McCullough probably did not begin their work on gratitude with me in mind. However, I am still inclined to say I feel grateful to them. (I am also grateful to each of them for taking a personal interest in my career and helping me in direct ways. But for the moment I am focusing on this other benefit they have provided.)

Indeed, about 150 out of 613 laws in the Torah concern sacrifice (Telushkin, 1991). But one might quibble slightly with the idea that they are all basically about gratitude per se. In fact, there are many kinds of sacrifices, such as ones prescribed at certain times (such as daily sacrifices and festival sacrifices; the traditionally religious Jewish schedule of prayer is intended on some level to stand in for, and to some extent replicate, the schedule of sacrifices in the Temple). Also, there are sacrifices of first fruits, peace offerings, sin offerings, cleansing of ritual impurity, and others. At some level of abstraction, one could say these are all about gratitude. But the general Hebrew word for sacrifice, korban, comes from the root meaning “closeness.’’ This suggests that the general point of sacrifice would be to bring people closer to God. Certainly gratitude is one element of this.

References

Appadurai A.. (1985). Gratitude as a social mode in South India Ethos. 13: 236–245

Aristotle. (1962). Nicomachean Ethics (trans. M. Ostwald). Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing. [Original work published 350 BCE]

Batson C. D. (1998). Altruism and prosocial behavior. In: Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G., (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology, volume 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill (pp. 282–316)

Baumgarten-Tramer F. (1938). “Gratefulness” in children and young people J. Genet. Psychol. 53: 53–66

Bonnie K. E., de Waal F. B. M. (2004). Primate social reciprocity and the origin of gratitude. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 213–229)

Buck R. (2004). The gratitude of exchange and the gratitude of caring: A developmental-interactionist perspective of moral gratitude. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E., (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford (pp. 100–122)

Cohen A. B., Hall D. E., Koenig H. G., Meador K. (2005). Social versus individual motivation: Implications for normative definitions of religious orientation Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 9: 48–61

Cohen A. B., Rankin A.. (2004). Religion and the morality of positive mentality Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 26: 45–57

Cohen A. B., Rozin P.. (2001). Religion and the morality of mentality J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81: 697–710

Danner D. D., Snowdon D. A., Friesen W. V. (2001). Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the Nun Study J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80: 804–813

Davidson R. J., Ekman P. (1994). Afterward: What are the minimal cognitive prerequisites of emotion?. In: Ekman P., Davidson R. J. (Eds.). Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press (pp. 232–234)

Doi T. (1973). Anatomy of Dependence New York: Harper

Ekman P. (1992). Are there basic emotions? Psychol. Rev. 99: 550–553

Ekman, P., and Davidson, R. J. (eds.) (1994). Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Emmons R. A. (2004). The psychology of gratitude: An introduction In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 3–16)

Emmons R. A., Crumpler C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 19: 56–69

Emmons, R. A., and McCullough, M. E. (eds.) (2004). Psychology of Gratitude, NY: Oxford

Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84: 377–389

Fitness J., Fletcher G. J. O. (1993). Love, hate, anger, and jealousy in close relationships: A prototype and cognitive appraisal analysis J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65: 942–958

Fredrickson B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2: 300–319

Fredrickson B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions Am. Psychol. 56: 218–226

Fredrickson B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 145–166)

Fredrickson B. L., Joiner T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upper spirals toward emotional well-being Psychol. Sci. 13: 172–175

Fredrickson B. L., Levenson R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions Cognit. Emotion 12: 191–220

Fredrickson B. L., Tugade M. M., Waugh C. E., Larkin G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84: 365–376

Galvin R.. (2004). Challenging the need for gratitude: Comparisons between paid and unpaid care for disabled people J. Sociol. 40: 137–155

Graham S., Barker G. P. (1990). The down side of help: An attributional-developmental analysis of helping behavior as a low-ability cue J. Educ. Psychol. 82: 7–14

Graham S., Hudley C., Williams E.. (1992). Attributional and emotional determinants of aggression among African-American and Latino young adolescents Dev. Psychol. 28: 731–740

Haidt J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment Psychol. Rev. 108: 814–834

Haidt J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In: Keyes C. L. M., Haidt J. (Eds.) Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-lived. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. (pp. 275–289)

Harker L., Keltner. D. (2001). Expressions of positive emotion in women’s college yearbook pictures and their relationship to personality and life outcomes across adulthood J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80: 112–124

Harpham E. J. (2004). Gratitude in the history of ideas. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 19–36)

Hill P. C., Pargament K. I. (2003). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality. Implications for physical and mental health research. Am. Psychol. 58: 64–74

Ide R.. (1998). “Sorry for your kindness”: Japanese interactional ritual in public discourse J. Pragmatics 29: 509–529

Izard C. E. (1992). Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion–cognition relations Psychol. Rev. 99: 561–565

John O. P., Donahue E. M., Kentle (1991). The “Big Five” Inventory: Versions 4a and 5 Berkeley, CA: University of California, Institute for Personality and Social Research

Keltner D., Shiota M. N.. (2003). New displays, new emotions: A commentary on Rozin and Cohen (2003) Emotion 3: 86–91

Komter A. E. (2004). Gratitude and gift exchange. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford (pp. 195–212)

Kotani M. (2002). Expressing gratitude and indebtedness: Japanese speakers’ use of “I’m sorry” in English conversation Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 35: 39–72

Markus H. R., Kitayama S.. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion and motivation Psychol. Rev. 98: 224–253

Maslow A. H. (1964). Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences New York: Penguin Books

McAdams D. P., Bauer J. J. (2004). Gratitude in modern life: Its manifestations and development. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 81–99)

McCraty R., Childre D. (2004). The grateful heart: The psychophysiology of appreciation. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E., (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 230–255)

McCullough M. E., Emmons R. A., Tsang J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82: 112–127

McCullough M. E., Kilpatrick S. D., Emmons R. A., Larson D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol. Bull. 127:249–266

McCullough M. E., Tsang J.-A. (2004). Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford(pp. 123–141)

McCullough M. E., Tsang J.-A., Emmons R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86: 295–309

McDougall W. (1929). Outline of Psychology New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

Naito T., Wangwan J., Tani M.. (2005). Gratitude in university students in Japan and Thailand J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 36: 247–263

Ortony A., Turner T. J. (1990). What’s basic about basic emotions? Psychol. Rev. 97: 315–331

Oveis, C., Cohen, A. B., and Keltner, D. (2005). Vagal tone: A Physiological Marker of Positive Personality and Emotionality. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley

Panksepp J.. (1992). A critical role for “affective neuroscience” in resolving what is basic about basic emotions Psychol. Rev. 99: 554–560

Park N., Peterson C., Seligman M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 23: 603–619

Peterson C., Seligman M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification Washington: American Psychological Association

Porges S. W. (1992). Vagal tone: A physiologic marker of stress vulnerability Pediatrics 90: 498–504

Reiser O. L. (1932). The biological origins of religion Psychoanal. Rev. 19: 1–22

Roberts R. C. (2004). The blessings of gratitude: A conceptual analysis. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford (pp. 58–78)

Roseman I. J. (1991). Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions Cognit. Emotion 5: 161–200

Roseman I. J. (2004). Appraisals, rather than unpleasantness or muscle movements, are the primary determinants of specific emotions Emotion 4: 145–150

Rozin P., Cohen A. B. (2003a). High frequency of facial expressions corresponding to confusion, concentration, and worry, in an analysis of naturally occurring facial expressions in Americans Emotion 3: 68–75

Rozin P., Cohen A. B. (2003b). Reply to commentaries: Confusion infusions, suggestives, correctives, and other medicines [Commentary] Emotion 3: 92–96

Samuels P. A., Lester D. (1985). A preliminary investigation of emotions experienced toward God by Catholic nuns and priests Psychol. Rep. 56: 706

Sayers D. L. (1967). Strong Poison. New York: Avon [Original work published 1930]

Sayers D. L. (1995) Busman’s Honeymoon. New York: HarperPaperbacks. [Original work published 1937]

Scheier M. F., Carver C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies Health Psychol. 4: 219–247

Schimmel S. (2004). Gratitude in Judaism. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 37–57)

Shelton C. M. (2004). Gratitude: Considerations from a moral perspective. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 259–281)

Shiota M. N., Campos B., Keltner D.. (2003). The faces of positive emotion: Prototype displays of awe, amusement, and pride Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1000: 296–299

Shiota M. N., Campos B., Keltner D., Hertenstein M. J. (2004). Positive emotion and the regulation of interpersonal relationships. In: Philippot P., Feldman R. S. (Eds.), Regulation of Emotion. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. (pp. 127–155)

Shweder R. A. (1994). “You’re not sick, you’ve just in love”: Emotion as interpretive system. In: Ekman P., Davidson R. J. (Eds.), Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. NY: Oxford. (pp. 32–44)

Shweder R. A., Haidt J. (2000). The cultural psychology of the emotions: Ancient and new. In: Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J. M. (Eds), Handbook of Emotions, 2 edition. New York: Guilford. (pp. 397–414)

Silvia P. J. (2005). What is interesting? Exploring the appraisal structure of interest Emotion 5: 89–102

Smith A. (1976). Theory of Moral Sentiments (6th ed.). Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. [Original work published 1790]

Smith C. A., Ellsworth P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48: 813–838

Solomon R. C. (2004). Foreword. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. v–xi)

Solomon R. C. (2002). Back to basics: On the very idea of “basic emotions” J. Theory Soc. Behav. 32: 115–144

Steindl-Rast D. (2004). Gratitude as thankfulness and as gratefulness. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 282–289)

Telushkin J. (1991). Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, its People, and its History New York: William Morrow and Company

Tesser A., Gatewood R., Driver M. (1968). Some determinants of gratitude J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 9: 233–236

Tracy J. L., Robins R. W. (2004). Show your pride: Evidence for a discrete emotion expression Psychol. Sci. 15: 194–197

Triandis H. C. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism Boulder, CO: Westview

Trivers R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism Q. Rev. Biol. 46: 35–57

Tsang J.-A., McCullough M. E. (2004). Appendix: Annotated bibliography of psychological research on gratitude. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E., (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 291–341)

Turner T. J., Ortony A. (1992). Basic emotions: Can conflicting criteria converge? Psychol. Rev. 99: 566–571

Watkins P.C. (2004). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In: Emmons R. A., McCullough M. E. (Eds.), Psychology of Gratitude. NY: Oxford. (pp. 167–192)

Watkins P. C., Grimm D. L., Kolts R. (2004). Counting your blessings: Positive memories among grateful persons Curr. Psychol. Dev. Learn. Pers. Soc. 23: 52–67

Weiner B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion Psychol. Rev. 92: 548–573

Weiner, B., Russell, D., and Lerman, D. (1978). Affective consequences of causal ascriptions. In Harvey, J. H., Ickes, W. J., and Kidd, R. F. (eds.), New directions in attribution research (Vol. 2), Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Weiner B., Russell D., Lerman D.. (1979). The cognition–emotion process in achievement related contexts J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37: 1211–1220

Yoshida M., Fujii K., Kurita J. (1966). Structure of a moral concept “on” in the Japanese mind: I Jpn. J. Psychol. 37: 74–85

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A review of Psychology of Gratitude. Edited by Robert Emmons and Michael McCullough. New York: Oxford, 2004. ISBN: 0-195-150-104, 384 pp.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, A.B. On Gratitude. Soc Just Res 19, 254–276 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-006-0005-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-006-0005-9