Abstract

This study examines adolescent depressive symptoms and the quantity and quality of time spent by adolescents with their parents and siblings. We use measures of the quality of relationships with parents and siblings as proxy indicators for the quality of time spent with these social partners. The study emphasizes the salience of parent relationships to adolescent depression. The structural equation models suggest that time spent with parents is indirectly linked with the severity of depressive symptoms via adolescents’ perceptions of how accepting their parents are of them, and the extent to which parents avoid exerting psychological control. We discuss these findings in relation to clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Depressive illness during adolescence impacts upon social, academic and interpersonal functioning, foreshadowing a difficult life-course (Weissman et al. 1999). It is associated with considerable burden of illness, is recurrent in nature, and later episodes may worsen in severity (Zisook et al. 2007). Even young people whose symptoms are not severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of depression may experience functional disturbances (Lewinsohn et al. 1999), and diminished quality of life (Bettge et al. 2008; Reinfjell et al. 2008).

As the peer group grows in salience during adolescence, the family is believed to have lessened influence on adolescent wellbeing compared to earlier ages. This supposition, however, has been debated, with some studies indicating that parents remain an important influence upon emotional wellbeing throughout adolescence (Reinfjell et al. 2008). This study examines whether time spent with family—specifically time with parents and time with siblings—is associated with level of depressive symptoms. When relating the quantity of time spent engaged in shared activity to adolescent depressed mood, the quality of interactions and relationships between adolescents and their parents and siblings must be taken into account. In families who spend more time together, parent-adolescent relationships are warmer and more loving, and adolescents report less depression (Crouter et al. 2004).

This article examines adolescent depressive symptoms and the quantity and quality of time spent with parents and siblings, using data from a large US study, the Child Development Supplement II (CDS II). Measures of the quality of relationships with parents and siblings are used as proxy indicators for the quality of time spent with these social partners. The findings presented form part of a larger analysis examining the associations between a variety of time use factors and adolescent depression. For simplicity, all components are not presented here. However, the model may be interpreted as adjusting for the contributions of these factors, in particular, the effects of time with peers, peer group acceptance and peer group deviance.

We test the hypothesis that spending more time engaged in activity with parents and siblings would be associated with lower depressive symptom severity, and that these relationships would be mediated by the quality of the adolescents’ relationships with these family members. Due to the higher prevalence of depression among females (Wade et al. 2002) and gender differences in the nature of parent-adolescent relationships (Starrels 1994), males and females were studied separately.

2 Methods

Cross sectional analyses were conducted on the 2002/2003 wave of data from the CDS II, an extension of the nationally representative Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID, Institute for Social Research 2005). A sample of 729 adolescents aged 13–18 years (including 67 pairs of siblings) and their primary care givers (93% were mothers) were selected for analysis. Excluded adolescents (25% of those in the eligible age range) were missing data on the outcome measure or had unreliable time-diary data. Using sample weights for study attrition and non-response, the weighted sample comprised 48% females, and had a mean age of 15.2 years (SD = 1.6). Sixty-three percent were European American, 19% African American, and 18% Hispanic or another minority group. The majority (76%) lived in two-parent families.

Adolescents completed open-ended 24 h time diaries for a randomly selected weekday and weekend day, and separate interviews were conducted with adolescents and primary caregivers. Depressive symptoms were measured on the short form of the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1992). The following independent variables were examined: (1) time spent in joint activity with parents or siblings (2) adolescent reported closeness to parents and siblings (4 point Likert scales) (3) psychological distress of the primary caregiver (parent report, using the short Kessler 6 (Kessler et al. 2002)), and (4) parent-adolescent relationships (adolescent perceptions of their parents’ acceptance and psychologically controlling behaviours, and parent reports of parent warmth (Barber and Olsen 1997)). Analyses controlled for socio-demographic factors (adolescent age, ‘only-child’ status, household income, parents’ educational attainment), adolescent physical health and self-concept, limitations in school and social participation, and the quantity and quality of time spent with peers.

Structural Equation Modeling was employed, using SPSS (Version 11, SPSS Inc. 2001) and AMOS (Version 6, Arbuckle 2003) software. Following the two step procedure recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), latent variables were tested individually in measurement models prior to examining the hypothesised structural models (path analysis). Models were generated separately for males and females on half of the sample, then cross-validated on the other half.

3 Results

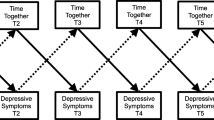

Univariate analyses revealed, for females only, a weak correlation between spending more time with parents and siblings and experiencing less depressive symptoms (Spearman’s Rho −.15 and −.16 respectively, p < .001). In the SEM analyses, model chi-square values were significant for both the male and female models, however other indices demonstrated acceptable model fit (e.g., Males: Modified χ2 = 2.4, RMSEA = .06, GFI = .94; Females: Modified χ2 = 1.8, RMSEA = .05, GFI = .96). The male and female models accounted for 48 and 50% of the variance in depressive symptoms, respectively. The simplified models for males and females are presented in Fig. 1. Regression weights are labeled on the paths between latent and observed variables (represented as ovals and rectangles respectively). Only significant associations (p < .05) (and no control variables) are shown.

Findings were similar across genders, indicating that time with parents was indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through parental acceptance. Adolescents who spent more time with parents perceived their parents to be more accepting and reported fewer depressive symptoms. For females only, more time spent with parents was associated with lower levels of parental psychological distress. Additionally, adolescents of both genders who reported a closer relationship with their parents perceived their parents to be more accepting and to exert less psychological control, and they also reported fewer depressive symptoms. Parental warmth towards the adolescent, time with siblings and closeness to siblings were not associated with adolescent depression in either model.

4 Discussion

This study confirms the central role of parents in adolescent depression. Although time spent with parents appears to offer an important protective effect, adolescents’ perceptions of the closeness of relationships with parents were also important. Moreover, the effects of these variables were indirect, via perceptions of the extent to which parents were accepting of the young person and avoided exerting psychological control. In contrast, neither the quantity nor quality of time with siblings was related to adolescent depression.

Strengths of this research include the use of a large representative sample, and the ability provided by Structural Equation Modeling to estimate the associations between the variables of interest while controlling for a range of other influences including demographic variables, peer group factors and measurement error (not shown in the figure). However, the use of cross-sectional data means that alternative causal pathways cannot be discounted. Thus it is possible that the existence of depressive symptoms results in young people avoiding time with their parents and perceiving their relationships with parents to be less positive. Depressed adolescents who share little time with parents may have restricted opportunities to practice social skills, with implications for the development and maintenance of support networks which are important for mental wellbeing. Future research is needed to determine the temporal relationship between depressive symptoms and poor adolescent-parent relationships, and could examine how this differs according to factors not explored in this study, such as parent gender and family structure.

It is notable that no relationships (direct or indirect) were found between parental psychological distress or parental warmth and adolescent depression. Both measures were parent reported, suggesting that adolescent perceptions of what is happening within the family, may be more important predictors of their mood than information collected from other perspectives. The absence of any relationship between time spent with siblings and depression may be due to unmeasured sibling characteristics. Other studies suggest that time spent in mixed-sex sibling dyads during adolescence may influence subsequent adjustment (Tucker et al. 2008), and that siblings may emulate each others’ internalizing behaviors (Fagan and Najman 2003). Thus, gender and the mental health of siblings should be taken into account in future investigations of shared time.

This study has implications for clinical work and the orientation of services for young people at risk for or presenting with depression. It highlights the importance, when working with young people, of assessing the accuracy of their perceptions of their family and family relationships and addressing these through cognitive restructuring when appropriate. This may require supplementary work with parents to ensure the use of parenting techniques that achieve a balance of monitoring and autonomy-encouragement appropriate to adolescence, and the development of quality parent-adolescent time, potentially focused around the activities and interests of young people. Overall, the study highlights the important influence of parents on adolescent depression and quality of life during this critical developmental period, and implies that clinicians ignore the family and family relationships potentially to the detriment of their clients.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and the recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2003). Amos (Version 5.0). Chicago: SPSS.

Barber, B. K., & Olsen, J. A. (1997). Socialization in context: Connection, regulation, and autonomy in the family, school, and neighborhood, and with peers. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12(2), 287–315.

Bettge, S., Wille, N., Barkmann, C., Schulte-Markword, M., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & The BELLA Study Group. (2008). Depressive symptoms of children and adolescents in a German representative sample: results of the BELLA study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 71–81.

Crouter, A. C., Head, M. R., & McHale, S. M. (2004). Family time and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66(1), 147–162.

Fagan, A. A., & Najman, J. M. (2003). Sibling influences on adolescent delinquent behaviour: An Australian longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 547–559.

Institute for Social Research. (2005). The panel study of income dynamics child development supplement. User Guide for CDS-II. From http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/CDS/cdsii_userGd.pdf. Retrieved 9 Jan 2006.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., Klein, D. N., & Seeley, J. R. (1999). Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder. I: Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 56–63.

Reinfjell, T., Hjemdal, O., Aune, T., Vikan, A., & Diseth, T. H. (2008). The pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 as an assessment measure for depressive symptoms: A correlational study with young adults. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62, 279–286.

SPSS Inc. (2001). SPSS advanced models 11.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

Starrels, M. E. (1994). Gender differences in parent-child relations. Journal of Family Issues, 15(1), 148–165.

Tucker, C. J., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2008). Links between older and younger adolescent siblings’ adjustment: The moderating role of shared activities. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32(2), 152–160.

Wade, R. J., Cairney, J., & Pevalin, D. (2002). Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 190–198.

Weissman, M. M., Wolk, S., Goldstein, R. B., Moreau, D., Adams, P., Greenwald, S., et al. (1999). Depressed adolescents grown up. Journal of the American Medical Association, 18(281), 1707–1713.

Zisook, S., Lesser, I., Stewart, J. W., Wisniewski, S. R., Balasubramani, G. K., Fava, M., et al. (2007). Effect of age at onset on the course of major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1539–1546.

Acknowledgments

Data are from the Child Development Supplement II of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. The PSID is primarily sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Aging, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and conducted by The University of Michigan. Dr. Nicholson was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Population Health Career Development Award (390136).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Desha, L.N., Nicholson, J.M. & Ziviani, J.M. Adolescent Depression and Time Spent with Parents and Siblings. Soc Indic Res 101, 233–238 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9658-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9658-8