Abstract

Consistent with objectification theory, the primary goal of the present study was to investigate the role of perceived humanization from one’s intimate partner as a predictor of depression (i.e., symptom severity), eating disorders (i.e., body dissatisfaction), and sexual dysfunction (i.e., dissatisfaction with quality of the sexual relationship) during pregnancy through decreased self-objectification. We tested our hypotheses within a dyadic framework, considering the respective contributions of humanization perceived by each partner to self-objectification and well-being in 159 U.S. heterosexual couples. Results converged with research linking partner humanization to lower levels of self-objectification in women. Further, feeling humanized by one’s partner also decreased self-objectification in men. Subsequently, lower levels of self-objectification were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and body dissatisfaction for both men and women and higher levels of sexual satisfaction for women. Our study also revealed the complex role of self-objectification in couple relationships: Less self-objectification by women, related to humanization from one’s partner, was associated with fewer depressive symptoms reported by their partners, but less self-objectification by men was, paradoxically, associated with more depressive symptoms reported by their partners. Results have implications for practitioners implementing couple and family interventions with pregnant women and their partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Diminished well-being of parents during pregnancy not only affects expectant mothers and fathers, but ultimately impacts birth outcomes and the health of their offspring (Dunkel Schetter and Tanner 2012; Pearlstein 2015). One factor potentially contributing to decrements in well-being is related to the visible changes to their bodies that women experience throughout gestation and the sense that one’s body no longer fits cultural ideals of attractiveness (Kukla 2005). Specifically, pregnant women might engage in habitual monitoring of their bodily appearance due to dehumanizing experiences with others in which their non-physical attributes are valued less than their physical attributes (Johnston-Robledo and Fred 2008; Rubin and Steinberg 2011).

In the present study, we examined the role of self-objectification during pregnancy in the form of body surveillance in predicting depression (i.e., depressive symptom severity), eating disorders (i.e., body dissatisfaction), and sexual dysfunction (i.e., sexual dissatisfaction). Further, within a dyadic framework with committed couples, we focused on humanization from one’s intimate partner during pregnancy as a predictor of reduced self-objectification. To derive testable hypotheses, we applied objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), which lays the foundation for our hypothesis that more favorable outcomes will result when one’s partner is perceived as humanizing and that this process will unfold through decreased self-objectification.

Objectification Theory

Objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997) represents a major advance in our understanding of the deleterious consequences of living in a culture that sexually objectifies women’s bodies. Women and men inhabit a culture saturated by sexual objectification in which women are persistently reduced to their bodily appearance with their physical attractiveness regarded as more important than their other attributes, such as their intelligence, kindness, morality, and health. According to objectification theory, women can gain predictability and control in their environments by adopting an observer’s perspective of their physical selves. By engaging in self-objectification—seeing the self as an object for other people’s consumption—women may be able to predict how others will treat them. One well-documented manifestation of self-objectification is persistent body surveillance (Moradi and Huang 2008)—habitual monitoring of one’s appearance (Mckinley and Hyde 1996). Self-objectification expressed as body surveillance predicts several adverse outcomes that disproportionately affect women compared to men, including depression, eating disorders, and sexual dysfunction (see Moradi and Huang 2008; Roberts et al. 2018; Szymanski et al. 2011).

Objectification theory utilizes a developmental perspective, explaining when and why changes in mental health risk develop or dissipate for girls and women as their bodies change over the lifespan (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). During puberty, for example, girls experience an uptick in sexual objectification as they develop reproductively mature bodies. Such objectifying experiences contribute to increases in self-objectification and related adverse outcomes. For example, self-objectification predicts disordered eating symptoms in young women aged 12–16-years-old, and body shame and appearance anxiety have emerged as mechanisms of this relation (Slater and Tiggemann 2002, 2010). Likewise, objectification theory suggests that middle age may be associated with decreases in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating and related mental health consequences if women are exposed to less sexual objectification and thereby self-objectify less. Consistently, body surveillance, appearance anxiety, and disordered eating decline with age and a reduction in self-objectification explains these reductions (McKinley 2006; Tiggemann and Lynch 2001).

Self-Objectification during Pregnancy

Another notable change that occurs in the lives of many women is pregnancy during which women’s reproductively mature bodies undergo visible changes. Similar to puberty, women may find that their bodies garner more attention from others during pregnancy, giving women the impression that other people value how they look more than their non-visible attributes. Scholars have suggested that pregnant bodies become “public domain,” with family, friends, and even strangers looking at, commenting on, and sometimes touching the bodies of pregnant women (Kukla 2005). On the one hand, some evaluations may be positive because pregnancy provides a visible marker that a woman’s body has been maternally successful, consistent with expectations regarding the feminine gender role (Dworkin and Wachs 2004; Johnston-Robledo et al. 2007; Stearns 1999). On the other hand, other appraisals may be markedly negative because pregnancy may undermine women’s ability to fit conventional standards of sexual attractiveness (e.g., thin; low waist-to-hip ratio).

Regardless, pregnancy is a time when women are often reminded that their current body “belongs less to them and more to others” (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997, p. 193). Indeed, simply showing women images of pregnant women (e.g., images of pregnant celebrities; images of pregnant women paired with reminders of their mortality) can increase the tendency for them to self-objectify (Goldenberg et al. 2007; Morris et al. 2014). Thus, we expect pregnant women to engage in habitual monitoring of their bodily appearance due to dehumanizing experiences with others in which their non-physical attributes are attended to less and valued less than their physical attributes. Further, we expect this manifestation of self-objectification to predict several outcomes posited by objectification theory, including depression (i.e., depressive symptom severity), eating disorders (i.e., body dissatisfaction), and sexual dysfunction (i.e., sexual dissatisfaction) (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Consistent with these notions, Rubin and Steinberg (2011) found that self-objectification was associated with depressive symptoms in pregnant women.

There are only a handful of known studies that examine the tenets of objectification theory in pregnant women (e.g., Johnston-Robledo and Fred 2008; Rubin and Steinberg 2011), and they have not considered relations between self-objectification and indicators of the other two outcomes posited by the objectification model—disordered eating and sexual dysfunction. Thus, additional studies are warranted to comprehensively test the tenets of objectification theory in pregnant women (Tiggemann and Williams 2012). The current study fills this critical gap in the literature by examining eating disorder symptoms (i.e., greater body dissatisfaction) as well as sexual dysfunction (i.e., less satisfaction with the quality of sex and sensuality in the couple’s relationship) in pregnant women.

Additionally, one difference from adolescence is that pregnancy is frequently experienced in the context of an intimate relationship, and it is possible that certain relationship processes may serve as protective factors for the adverse outcomes predicted by objectification theory. To illustrate, although it is possible that an expectant mother may perceive dehumanization from the expectant father, it is also possible she will perceive increased humanization (e.g., perceiving higher concern about her health and comfort). Such perceived humanization may predict less self-objectification, reducing the likelihood that she will report indicators of depression, eating disorders, or sexual dysfunction. After all, compared to other people who have little to no knowledge about pregnant women’s internal attributes, some expectant fathers may keenly appreciate all that their partner is doing to assure the birth of a healthy child. Furthermore, expectant fathers may bring their own perceptions (e.g., partner humanization; self-objectification) which may contribute not only to their own well-being, but also to the mother’s. Indeed, although objectification theory and related research focuses primarily on girls and women, there is research showing that men also sometimes engage in self-objectification (albeit less than women) with adverse consequences (Grieve and Helmick 2008; Morry and Staska 2001; Oehlhof et al. 2009; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005).

In summary, the present study makes several contributions to the literature on objectification during pregnancy. As we previously noted, there are few studies (e.g., Rubin and Steinberg 2011) that have applied objectification theory to understand adverse outcomes for pregnant women, even though many women will become pregnant during their lifetimes and may experience a noticeable rise in objectifying experiences during this time. Further, little research has examined self-objectification in the context of heterosexual romantic relationships. Of the limited studies that have examined objectification in relationships, research suggests that more partner humanization and less self-objectification contribute to positive outcomes for women. For example, Sáez et al. (2019) found that for women in committed relationships, feeling humanized by one’s partner was related to increased body satisfaction and overall relationship satisfaction (also see Meltzer and McNulty 2014; Ramsey and Hoyt 2015; Ramsey et al. 2017; Zurbriggen et al. 2011).

Furthermore, of the few known studies that have examined objectification in couples, it appears that self-objectification in one partner predicts self-objectification in the other partner (Strelan & Pagoudis, 2018). It is also possible, though to date untested, that self-objectification in one partner may diminish well-being in the other partner. Alternatively, both partners might experience positive outcomes (i.e., less self-objectification and less mental health disorders) to the extent that they feel as though their partners see them as a fellow human being. Thus, the couple relationship has the potential to serve a powerful role in dismantling a pervasive culture of sexual objectification that has culminated in harmful self-objectification processes that undermine the well-being of women and men.

Overview of the Present Work

In the present study, we tested objectification theory in pregnant couples with self-objectification predicting outcomes originally theorized by objectification theory, including depression (i.e., depressive symptom severity), eating disorders (i.e., body dissatisfaction), and sexual dysfunction (i.e., sexual dissatisfaction) (Rust and Golombuck 1985). We utilized the actor-observer model (see similar approaches by Garcia et al. 2016; Strelan & Pagoudis, 2018) to explore whether the effects held for expectant mothers and fathers. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to apply this objectification framework to the study of pregnant couples.

Generally speaking, pregnancy increases the likelihood of experiencing diminished well-being. Turning first to depression, pregnancy increases the likelihood of presenting with depressive symptoms; studies show that 14–23% of women experience a depressive episode while pregnant (Yonkers et al. 2009), and a meta-analysis (Bennett et al. 2004) revealed that the prevalence of full-fledged depression is high in the first (7.4%), second (12.6%), and third (12.0%) trimesters. Not only is prenatal depression associated with postpartum depression in women (Beck 2001), but it is also associated with higher likelihood of premature delivery (Grigoriadis et al. 2013).

Some studies suggest that the connection between pregnancy and depression can be explained, in part, by body-related issues. For example, body dissatisfaction has been linked to depression for pregnant women in the second and third trimesters (Clark et al. 2009; Duncombe et al. 2008; Rauff and Downs 2011; Silveira et al. 2015). Of particular relevance to the present paper, Rubin and Steinberg (2011) found a moderate positive correlation between body surveillance and depression in pregnant women. At the same time, it is possible that when pregnant women feel humanized by their partner (i.e., feeling like your partner sees beyond your pregnant body and values you for your many attributes such as intelligence, humor, and kindness), they will experience less depression, and one mechanism explaining this link is reduced self-objectification. Having a partner who values them for their non-physical attributes may be associated with fewer depressive symptoms in pregnant women. Not only does perceived partner humanization contribute to greater relationship satisfaction which may ward off the tendency to become depressed (Sáez et al. 2019), but it also may combat the increased self-objectification that pregnant women experience as visible changes manifest in their bodies. Thus, we expected (Hypothesis 1): (a) more perceived partner humanization to be associated with less depressive symptoms, (b) more perceived partner humanization to be associated with less self-objectification, (c) less self-objectification to be associated with less depressive symptoms, and (d) less self-objectification to emerge as a mediator of the link between more humanization and depression.

We also tested this model for body dissatisfaction as a core symptom of eating disorders, an outcome posited by objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Research suggests that self-objectification during pregnancy is associated with less likelihood of engaging in a variety of healthy behaviors (e.g., not getting enough sleep), including behaviors related to eating (e.g., not drinking milk, eating dairy products, or taking calcium supplements; Rubin and Steinberg 2011). Although this past research focused on pregnancy did not focus explicitly on disordered eating symptoms, there is a wealth of research suggesting that self-objectification is associated with body dissatisfaction and symptoms of disordered eating (Noll and Fredrickson 1998; Prichard and Tiggemann 2005; Stice and Shaw 2004; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tylka and Hill 2004) in non-pregnant women. Even if the chances of it are relatively low during pregnancy, when present, disordered eating symptomology is associated with many negative outcomes for the child, including low birth weight, prematurity, and miscarriage (Micali et al. 2007). We expected (Hypothesis 2) that feeling humanized would be related to less severe eating disorder symptoms manifested as less body dissatisfaction. Even if their bodies no longer fit cultural ideals of attractiveness, pregnant women who feel that their partner values them for their non-physical attributes may be less likely to reduce themselves to their physical selves. Consistently, partner humanization is associated greater body satisfaction for heterosexual women in committed relationships (Sáez et al. 2019), supporting our hypothesis that partner humanization might decrease body dissatisfaction through decreased self-objectification.

We explored this same model for sexual satisfaction. While objectification theory originally focused on sexual dysfunction specifically (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), objectification researchers usually assess this construct more generally by measuring sexual desire, arousal, ability to achieve orgasm, and/or sexual satisfaction (Steer and Tiggemann 2008; Tiggemann and Williams 2012). Indeed, relationship theorists consider sexual dysfunction and sexual dissatisfaction as inextricably connected (Rust and Golombuck 1985). Furthermore, because the current study included couples, we were uniquely poised to assess sexual satisfaction in both members of the dyad, addressing not only an individual outcome of self-objectification but also a relational outcome. Research shows that many women experience less sexual desire and reductions in sexual activity and vaginal intercourse in particular as a pregnancy progresses (Bartellas et al. 2000; see also Byrd et al. 1998), and depression is an important predictor of reduced sexual desire and sexual activity (De Judicibus and McCabe 2002). Furthermore, if women experience more sexual objectification and related self-objectification, then they might think more about how their bodies look and less about their internal sexual pleasure during sexual interactions, thereby undermining their sexual satisfaction. However, when women perceive that their partner values their human attributes, they may be able to better focus on their own sexual pleasure during sexual interactions, contributing to more sexual satisfaction. Thus, as with depressive symptoms and body dissatisfaction, we expected partner humanization to increase sexual satisfaction through decreased self-objectification (Hypothesis 3).

Because we administered measures to both members of the dyad, we also explored whether the same relations hypothesized for expectant mothers emerged for expectant fathers. Although objectification theory suggests that the effects of self-objectification should be most pronounced for women (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), research examining self-objectification and related consequences in couples shows that men sometimes experience a similar (albeit less pronounced) pattern of relations (Strelan & Pagoudis, 2018). Further, despite men’s expanding roles as caregivers, there has been surprisingly little research on fathers, particularly expectant fathers. In this sparse literature, it appears that pregnancy also undermines well-being in men. Research shows that expectant fathers, for example, present with depressive symptoms (10%) and paternal depression is associated positively with maternal depression (Paulson and Bazemore 2010), suggesting that dyadic processes may be involved. Thus, we explored whether similar relations emerged for expectant fathers as mothers.

Finally, we explored whether dyadic effects emerged such that (a) perceived humanization relates to partner self-objectification or (b) self-objectification relates to partner measures of well-being. However, of the very limited objectification research conducted with dyads, the results have been conflicting. Some research has yielded significant partner effects in both women and men (Strelan & Pagoudis, 2018). Other research has found partner effects, but only for women (Garcia et al. 2016). And still other research has revealed no partner effects at all (Mahar et al. 2020). Thus, we expected more perceived humanization and less self-objectification to predict better outcomes not only for self, but also for one’s partner similar to the actor hypotheses that stem directly from objectification theory, but this prediction was more exploratory in nature.

Method

Participants

There were 162 cohabitating U.S. couples who enrolled in our study. Three couples were excluded due to either invalid data or ineligibility, yielding a final sample of 159 heterosexual couples (159 women and 159 men). Couples had dated an average of 81.90 months (SD = 49.59, range = 5.06–21.12), cohabited an average of 61.00 months (SD = 41.80, range = .32–202.76), and were typically married (n = 135, 84.9%). Over half (n = 92, 57.8%) reported that they had no children (i.e., first-time parents), and those who had children living in the home had a mode of 1 child. Most women were in the second (n = 61, 38.4%) or third (n = 93, 58.5%) trimester of pregnancy. Participants were primarily White (n = 142, 89.3% of women; n = 139, 87.4% of men); .6% (n = 1) of women and .6% (n = 1) of men identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native; 2.5% (n = 4) of women and 2.5% (n = 4) of men identified as Asian; .6% (n = 1) of women and 3.8% (n = 6) of men identified as Black or African American; 6.9% (n = 11) of women and 5.7% (n = 9) of men identified as more than one race; 9.4% (n = 15) of women and 6.4% (n = 10) of men identified as Hispanic or Latino. On average, women were 28.67 years of age (SD = 4.27, range = 19–40) and men were 30.56 years of age (SD = 4.52, range = 19–49). The sample reported a median joint income of $60,000 to $69,999, and most participants were employed at least 16 h per week (n = 118, 74.2% of women; n = 146, 91.8% of men). Further, the modal education was a bachelor’s degree (n = 74, 46.5% of women; n = 55, 34.6% of men).

Procedures and Measures

Flyers and brochures were broadly distributed to businesses and clinics frequented by pregnant women (e.g., obstetric clinics). Further, if an establishment permitted, members of the research team approached potential participants and provided a short, 5-min overview of the study along with a brochure. Eligibility criteria included: (a) 19 years of age or older (legal age of adulthood where the research was conducted), (b) English speaking, (c) pregnant at the time of the initial appointment (but not necessarily the first pregnancy to increase generalizability of results), (d) both partners are biological parents of the child, (e) singleton pregnancy, and (f) in a committed intimate relationship and cohabiting.

All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board prior to data collection. Both partners attended a 3-h laboratory appointment during which they completed behavioral observation tasks, semi-structured clinical interviews about the quality of their intimate relationships, and self-report questionnaires. Partners were escorted to separate rooms to complete the clinical interviews and self-report questionnaires and did not interact with one another until the procedures were complete. Participants were compensated with $50 (for a total of $100 per couple) for attending the appointment.

Perceived Humanization by Partner

We included a one-item measure that has been used in previous work to assess the degree to which people feel humanized by their partner (Sáez et al. 2019; see also Meltzer and McNulty 2014): “To what extent do you believe your relationship partner values you for your non-physical qualities (e.g., intelligence, fun, creativity, ambition, kindness, generosity, patience, career success, trustworthiness, ability to solve problems, humor, loyalty, and supportiveness)?” Participants provided their rating on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). Previous research using this item has shown that perceived humanization is associated with lower levels of body dissatisfaction as well as higher levels of relationship satisfaction in college women (Sáez et al. 2019). In the present study, humanization was relatively high, on average (for women: M = 4.57, SD = .65, mdn = 5; for men: M = 4.66, SD = .58, mdn = 5).

Self-Objectification

The Body Surveillance subscale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS, Mckinley and Hyde 1996) was used to assess self-objectification. Participants rated the degree to which they persistently monitored their bodily appearance on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The Body Surveillance subscale contains eight items, including “During the day, I think about how I look many times” and “I rarely worry about how I look to other people” (reverse coded). Although this scale was originally developed and validated for use with women, it has also been used with men (Wiseman and Moradi 2010). Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating more self-objectification. Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .85 for women and α = .75 for men).

Depressive Symptoms

The General Depression scale of the expanded form of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II; Watson et al. 2012) was implemented. Respondents rated their feelings and experiences during the past 2 weeks based on given statements on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The general depression subscale consists of 20 items, including “I felt inadequate” and “I felt discouraged about things.” Item responses were summed, and possible scores can range from 20 to 100. Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .86).

Body Dissatisfaction

Body dissatisfaction was assessed with the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI; Forbush et al. 2013; Forbush et al. 2014). The EPSI is a factor analytically derived scale of eating disorder symptoms. The Body Dissatisfaction scale consists of seven items (e.g., “I did not like how clothes fit the shape of my body” and “I did not like how my body looked”) and taps into the higher-order shared dimension among eating disorder symptoms. Further, this scale has demonstrated strong convergence with established measures of eating disorder symptoms, and it has demonstrated utility for differentiating patients with eating disorders from patients with other forms of psychopathology. Participants respond on a scale of 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Items responses were summed and possible scores can range from 0 to 28. In the present sample, there was strong internal consistency (α = .88).

Satisfaction with Sexual Relationship

Participants completed a semi-structured interview during the laboratory appointment—the Relationship Quality Interview (RQI; Lawrence et al. 2011; Lawrence et al. 2009) —during which they answered a series of questions about various domains of their intimate relationships. This interview included a detailed discussion about multiple features of the sexual relationship including frequency of sex, satisfaction with the sexual relationship, the presence or absence of negative emotions during sex, any sexual difficulties experienced by either partner, and the occurrence and quality of sensual behaviors (e.g., hugging, massage). After discussing this area of the relationship, participants were asked to respond to a single item: “On a scale of 1 to 9, how satisfied have you been with your sexual relationship or sensuality in your relationship in the last 6 MONTHS?,” using a scale of 1 (completely dissatisfying) to 9 (exceptionally satisfying).

Data Analytic Approach

To test the hypothesized model for each of the three outcomes (symptoms of depression, symptoms of eating disorders, and sexual satisfaction), we implemented path analysis in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2010). Missing data were minimal (covariance coverage ranged from .98 to 1.00); Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to address missing data (Enders 2010). To account for violations of normality, we performed a nonparametric resampling method (bias-corrected bootstrap) with 5000 resamples drawn to derive the 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects (Preacher et al. 2007). Consistent with actor-partner interdependence modeling (APIM) for distinguishable dyads (Kenny et al. 2006), we covaried the residuals of endogenous variables (i.e., maternal and paternal self-objectification; maternal and paternal outcomes). There were two sets of effects for those models: (a) X affects own Y (actor effects; e.g., self-objectification of the woman predicting her depressive symptoms) and (b) X affects partner’s Y (partner effects; e.g., self-objectification of the woman predicting her partner’s depressive symptoms). Finally, several variables (e.g., age, marital status, week of pregnancy, relationship duration, first-time parenthood status) were examined as potential covariates; however, given that these variables were neither correlated with predictors nor outcomes in the model, they were not included in the final tested models.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are reported in Table 1. As expected, higher levels of self-objectification were significantly correlated with more depressive symptoms and greater body dissatisfaction and lower levels of satisfaction with the sexual relationship for both men and women. As expected, perceived humanization was relatively high in this community sample of pregnant couples, and humanization by one’s partner was associated with less self-objectification reported by women, but not men. Gender differences were observed. Paired sample t-tests revealed that levels of self-objectification, t(155) = 6.19, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .50, depressive symptoms, t(158) = 2.95, p = .004, Cohen’s d = .23, and body dissatisfaction, t(158) = 8.41, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .67, were higher for women relative to men. The three outcomes of interest—depressive symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and sexual (dis)satisfaction—had small-to-moderate correlations.

Model Testing

Model #1: Depressive Symptoms

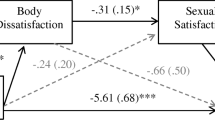

Model results are reported in Table 2 and Fig. 1a. Significant indirect effects were detected via intrapersonal (actor) paths. For women (95% CI [−1.599, −.130]) and men (95% CI [−1.279, −.094]), greater humanization predicted less severe depressive symptoms via decreased self-objectification. Further, reduced self-objectification associated with humanization perceived by women was associated with lower levels of men’s depressive symptoms (partner path) (95% CI [−1.243, −.013]). (Note that the direct association between women’s self-objectification and men’s depressive symptoms did not reach significance; however, the indirect effect was significant which can happen in the context of mediation; Hayes 2013). Another partner indirect effect emerged, but in the opposite direction than we expected. Specifically, greater humanization perceived by men was associated with lower levels of self-objectification by men, but this predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms in women (95% CI [.044, .951]).

Standardized coefficients are reported for key paths. Significant paths are represented by solid arrows whereas nonsignificant paths are represented by dashed arrows. Please refer to Tables 2, 3 and 4 for estimates of all direct effects in the tested models, along with the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals for each path. Although not depicted, we covaried the residuals of partner reports of self-objectification and partner reports of respective outcomes in each model

Model #2: Body Dissatisfaction

Model results are reported in Table 3 and Fig. 1b. Significant indirect effects were detected via intrapersonal (actor) paths. For women (95% CI [−1.688, −.063]) and men (95% CI [−1.106, −.124]), greater humanization predicted less body dissatisfaction via decreased self-objectification. No partner paths were significant in this model.

Model #3: Sexual Satisfaction

Model results are reported in Table 4 and Fig. 1c. To the extent that women reported more perceived humanization by their partners, they engaged in less self-objectification, and this was associated with higher sexual satisfaction (95% CI [.004, .242]). Humanization and self-objectification by either partner was not significantly associated with men’s satisfaction with the sexual relationship.

Supplementary Multiple Group Analysis

A multiple-group analysis was conducted to determine whether there was invariance in the models as a function of trimester of pregnancy. Given that only five couples attended the laboratory appointment during the first trimester, those couples were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient size of the subgroup. Each of the three models was tested with the paths (a) free to vary between two groups (i.e., second trimester versus third trimester) and (b) fixed to be equal between the groups. For each of the outcomes, Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978) and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC; Akaike 1974) were examined to evaluate relative fit of the models. Note that Chi-square difference tests were not appropriate for model comparisons given that the models that were free to vary between the groups were just identified. These values were the smallest for the models with parameters fixed to be equal between the groups relative to the model free to vary between the groups, suggesting that the more parsimonious fixed model (without differences) was the better fit: depression (free AIC = 4722.29/BIC = 4886.28; fixed AIC = 3594.56/BIC = 3713.01), eating pathology (free AIC = 4384.21/BIC = 4548.21; fixed AIC = 3221.06/BIC = 3339.50), and sexual satisfaction (free AIC = 4071.76/BIC = 4235.75; fixed AIC = 2551.78/BIC = 2670.22). Thus, the findings did not vary as a function of trimester of pregnancy.

Discussion

Objectification theory has advanced our understanding of deleterious consequences of living in a culture saturated with sexual objectification of women (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). The present investigation extended objectification theory by contributing to the limited literature on self-objectification and its correlates during pregnancy. Additionally, it is the first known study to examine self-objectification in expectant fathers. Finally, it is the only known investigation to date to examine the dyadic relations among humanization, self-objectification, mental health, and relationship outcomes in expectant mothers and fathers. Generally speaking, results of the present study provide support for the hypothesized model linking perceived humanization by one’s partner to adaptive outcomes via decreased self-objectification.

Actor Pathways

We examined self-objectification and its correlates during pregnancy—a time when the relations posited by objectification theory may be more pronounced because women experience a surge in sexual objectification. At the same time, it is also possible that pregnancy may represent a unique period in the lives of women when the tenets of objectification theory simply do not apply—women may stop comparing their bodies to other women, they may care about comfort more than fashion, and they may be more concerned with the health of their baby than the appearance of their body. Although we found relatively low levels of self-objectification overall, the pattern of significant relations was consistent with objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Specifically, if pregnant women reported feeling humanized by their partners, they experienced lower levels of self-objectification. This is consistent with past research demonstrating the deleterious effects of partner objectification on self-objectification among non-pregnant women (Ramsey et al. 2017).

The present investigation is the first known to consider self-objectification and its correlates for expectant fathers. Gender roles are evolving and expectant fathers are taking more active roles in parenthood (Cabrera et al. 2018), and research identifying correlates of their well-being during pregnancy is sorely needed in the literature. Because objectification theory was developed to explain the deleterious consequences of living in cultures that persistently sexualize women’s bodies and objectification research shows stronger effects for women than men (Roberts et al. 2018), it was unclear whether the tenets posited by objectification theory would hold for expectant fathers. Consistent with objectification theory, results of the present study demonstrated that if expectant fathers felt humanized by their partners, they also reported lower levels of self-objectification. More generally, no previous known studies have explored the consequences that men experience as a result of dehumanizing (or humanizing) experiences with their partners. Thus, the current research expands the study conducted by Ramsey and collaborators (2017) by showing that men’s self-objectification is negatively associated with the degree to which their partners value them for more than their physical attributes. Because our work was done with expectant fathers, it would also be useful to examine whether the same relations emerge for men at times other than their partners’ pregnancy.

Although the actor associations between perceived humanization and self-objectification were parallel for expectant mothers and fathers, the outcomes articulated by objectification theory varied somewhat for men versus women. For women, lower levels of self-objectification were associated with fewer depressive symptoms, less body dissatisfaction, and greater satisfaction with the sexual relationship. Thus, if women perceive their partners as valuing them for attributes other than their appearance (partner humanization), this is linked to less body surveillance and, subsequently, more adaptive outcomes. Stated differently, if pregnant women do not feel humanized by their partners, this puts them at risk for adverse outcomes—a finding that converges with research demonstrating similar negative outcomes in response to general objectification experiences (e.g., exposure to objectification in the media or unspecified others, Moradi and Huang 2008; Roberts et al. 2018).

For men, decreased self-objectification was associated with fewer depressive and eating pathology symptoms, but not sexual satisfaction. Thus, if men engaged in greater body surveillance, they reported feeling inadequate or discouraged as well as symptoms of disordered eating, consistent with objectification theory. Interestingly, self-objectification did not undermine the satisfaction expectant fathers derived from their sexual relationship with their intimate partner, in contrast to other studies showing that more self-objectification is associated with less sexual satisfaction in college men (Zurbriggen et al. 2011). It is possible that the effects between self-objectification and sexual satisfaction are less pronounced as men age and/or transition to fatherhood. Future research is needed to directly examine this possibility.

Partner Pathways

Additionally, our research is the only study to our knowledge to examine the dyadic associations posited by objectification theory in expectant mothers and expectant fathers.

Using a dyadic framework with couples, we were also able to generate preliminary findings regarding partner effects of humanization and self-objectification. There were two partner effects that reached significance, both in the model explaining depressive symptoms. First, to the extent that women reported feeling less humanized by their partners, this perception was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in men through enhanced self-objectification reported by women. In other words, the less humanized women felt by their partners, the stronger women’s own self-objectification, which, in turn, was linked to their partners’ (men’s) higher depressive symptoms.

Second, in contrast to the previously discussed partner effect that suggests men benefit from women being humanized, we found that women were actually at elevated risk for depressive symptoms if men were humanized and reported less self-objectification. Specifically, less self-objectification reported by men as a result of feeling more humanized by their partners was actually associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in women. Or, interpreted in the reverse direction, men’s lower perceived humanization from their partner is associated with men’s stronger self-objectification, which, in turn, is linked to fewer depressive symptoms reported by their pregnant partners. Given that self-objectification is often used by less powerful individuals to exert some control over their environments (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), it is possible that in relationships in which men self-objectify, there are more equal power dynamics between partners, reducing women’s depressive symptoms. Because the few studies that have used a dyadic framework to examine objectification theory yielded inconsistent findings (Garcia et al. 2016; Mahar et al. 2020; Strelan and Pagoudis 2018), our hypotheses are undoutedly exploratory in nature. However, these initial findings suggest that the effects of self-objectification in one partner on depressive symptoms in the other partner may depend on gender (Garcia et al. 2016). It is also interesting to note that no dyadic effects emerged for sexual satisfaction or body dissatisfaction among our expectant mothers and fathers.

Summary of Findings and Implications for Couples Research

Together, our findings are consistent with objectification theory and related research, but also paint a more nuanced picture than previous research. In addition to depression, our research suggests that self-objectification is associated with disordered eating symptomatology (i.e., body dissatisfaction) as well as sexual dysfunction symptoms (i.e., sexual dissatisfaction) in expectant mothers. For expectant fathers, self-objectification was associated with more depressive symptoms and body dissatisfaction, but was unrelated to sexual satisfaction. Our focus on humanization as a predictor of reduced self-objectification and more adaptive outcomes for couples during pregnancy also represents a contribution to the objectification literature. Although sexual objectification experiences are clearly associated with many negative outcomes, our work suggests that humanization in couples could serve as an antidote for the negative cultural climate that promotes sexual objectification of women’s bodies and exerts negative consequences for both women and men.

The present study also has implications for the study of intimate relationships more broadly. Increasingly, couples researchers embrace a multifaceted approach to studying couples, recognizing the unique contributions of various processes unfolding in the relationship (e.g., support in response to stress and adversity, strategies for navigating disagreements; Brock et al. 2016). Nonetheless, the degree to which partners feel as though they are appreciated for multiple personal attributes other than physical appearance (i.e., the extent to which they feel humanized by their partners) has been largely overlooked in research with a few exceptions (Meltzer and McNulty 2014; Sáez et al. 2019). It is noteworthy that partner humanization represents a dimension of the intimate relationship that is closely related to other relationship processes that have received some empirical attention, such as respect and acceptance (e.g., feeling as though my partner looks up to me, appreciates me, and accepts me for who I am; Lawrence et al. 2011, Lawrence et al. 2009). Yet, the extent to which someone feels as though their worth is not reducible to their physical appearance appears to be a distinct but also vital relationship dimension that has the potential to explain a range of important outcomes. As such, couples researchers might benefit from more explicitly measuring humanization processes in intimate relationships and integrating them into existing theoretical frameworks. In particular, efforts to identify risk factors for low levels of humanization—including those that are embedded within the relationship (e.g., low levels of emotional intimacy)—should be explored in future research. Further, examining these processes during pregnancy, a unique period of time for couples when relationship dynamics are evolving and changing (Lawrence et al. 2010), appears to hold promise for understanding how to set couples on a healthy trajectory after childbirth.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There were several limitations to the present study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, data were cross-sectional and causal conclusions cannot be drawn about the tested pathways. Nonetheless, the direction of the effects has strong support from objectification theory (see Roberts et al. 2018, for a review). The next step in this line of research will be to test the hypothesized pathways over time using a longitudinal research design. Second, the sample comprised U.S. heterosexual, cohabiting couples who were largely White and from middle-class backgrounds, which limits the generalizability of the results; research investigating similar processes in sexual minority couples, across cultures, and with ethnically/racially diverse, lower-income couples is warranted.

Third, our measure of humanization in intimate relationships included one self-report item and measured perceived humanization rather than using more objective measures of humanization (e.g., actual partner humanization; behavioral indicators of humanization). We used this item as a measure of perceived humanization because it is the only known measure in the published literature (Sáez et al. 2019; see also Meltzer and McNulty 2014). More generally, future research is needed to more comprehensively test how objectification operates in intimate relationships with new and refined measures developed and validated specifically with couples, especially given previous research that has modified existing measures developed outside of couples has shown low reliability (e.g., objectified body consciousness scale to assess partner objectification; Zurbriggen et al., 2011). Additionally, measures of humanization and self-objectification used in the present study have not been validated with pregnant women. In particular, it is possible that body surveillance manifests in unique ways for women as they relate to their pregnant bodies (e.g., gaining weight in their mid-sections; showing that a “baby bump” may be related to less body dissatisfaction in women than gaining weight in other parts of the bodies). A questionnaire developed to assess self-objectification and related consequences during pregnancy might better capture this experience.

Finally, it remains unclear whether the current pattern of results is specific to couples experiencing pregnancy. Because we did not assess relations between these variables prior to pregnancy, the pattern of results may represent the status quo in a relationship or a change in the status quo due to pregnancy. Future research utilizing longitudinal designs would be helpful in answering this question. Further, there is a need for systematic investigations of the unique ways women might relate to their bodies during pregnancy, how these body perceptions connect to self-objectification processes, and the sources of both resiliency (e.g., partner humanization) and risk (e.g., partner objectification) arising from within the intimate relationship between expectant parents.

Practice Implications

The present work has implications for interventions aimed at promoting the health and well-being of parents navigating pregnancy, especially women who are experiencing significant bodily changes. Numerous interventions are already routinely implemented during pregnancy (e.g., birthing classes and parenting programs). These interventions might be enhanced by educating men about the challenges facing women as their bodies change throughout pregnancy in a society that emphasizes thinness. Further, providing instruction in tangible ways to convey appreciation for the non-physical attributes of partners (e.g., praising accomplishments at work, sharing appreciation for one’s sense of humor) might be particularly important for women who, during pregnancy, might feel as though they are appreciated more for the reproductive functions of their bodies than other significant non-physical qualities.

Conclusion

Objectification theory provides a framework for understanding how girls and women experience body changes over the lifespan while navigating a culture that perpetuates harmful self-objectification processes that undermine well-being. Yet, despite this developmental perspective, objectification theory has rarely been applied during pregnancy when women’s reproductively mature bodies undergo visible changes. Results of the present study add to a growing literature (e.g., Rubin and Steinberg 2011) suggesting that self-objectification is not only associated with increased depressive symptoms during pregnancy, but also elevated body dissatisfaction (a core feature of eating disorders) and sexual dissatisfaction. Further, by applying objectification theory with couples, rather than focusing exclusively on pregnant women, we demonstrated that through humanization, intimate partners have the potential to serve a powerful role in dismantling harmful cultural messages culminating in self-objectification. Indeed, we anticipate that intimate partners play a central role in reducing (or perpetuating) self-objectification throughout adulthood, not just during pregnancy. As such, future research should prioritize applying objectification theory with couples across different stages (e.g., dating, pregnancy, during older adulthood) to identify intervention priorities, such as increasing partner humanization of one another, for reducing self-objectification and its harmful consequences.

References

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. In E. Parzen, K. Tanabe, & G. Kitagawa (Eds.), Selected papers of Hirotugu Akaike. Springer series in statistics (perspectives in statistics) (pp. 215–222). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_16.

Bartellas, E., Crane, J. M. G., Daley, M., Bennett, K. A., & Hutchens, D. (2000). Sexuality and sexual activity in pregnancy. British Journal of Obsetrics and Gynaecology, 107, 964–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10397.x.

Beck, C. T. (2001). Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nursing Research, 50, 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004.

Bennett, H. A., Einarson, A., Taddio, A., Koren, G., & Einarson, T. R. (2004). Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103, 698–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f.

Brock, R. L., Kroska, E., & Lawrence, E. (2016). Current status of research on couples. In T. Sexton & J. Lebow (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy (pp. 409–433). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Byrd, J. E., Hyde, J. S., DeLamater, J. D., & Plant, E. A. (1998). Sexuality during pregnancy and the year postpartum. Journal of Family Practice, 47, 305–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499609551826.

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12, 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12275.

Clark, A., Skouteris, H., Wertheim, E., Paxton, S., & Milgrom, J. (2009). The relationship between depression and body dissatisfaction across pregnancy and the postpartum: A prospective study. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308097940.

De Judicibus, M. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2002). Psychological factors and the sexuality of pregnant and postpartum women. The Journal of Sex Research, 39, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552128.

Duncombe, D., Wertheim, E. H., Skouteris, H., Paxton, S. J., & Kelly, L. (2008). How well do women adapt to changes in their body size and shape across the course of pregnancy? Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308088521.

Dunkel Schetter, C., & Tanner, L. (2012). Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680.

Dworkin, S. L., & Wachs, F. L. (2004). Getting your body back: Postindustrial fit motherhood in shape fit pregnancy magazine. Gender & Society, 18, 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204266817.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Publications.

Forbush, K. T., Wildes, J. E., & Hunt, T. K. (2014). Gender norms, psychometric properties, and validity for the eating pathology symptoms inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22180.

Forbush, K. T., Wildes, J. E., Pollack, L. O., Dunbar, D., Luo, J., Patterson, K., … Watson, D. D. of P. S. (2013). Development and validation of the eating pathology symptoms inventory (epsi). Psychological Assessment, 25, 859–878. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032639.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Garcia, R. L., Earnshaw, V. A., & Quinn, D. M. (2016). Objectification in action: Self- and other-objectification in mixed-sex interpersonal interactions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315614966.

Goldenberg, J. L., Goplen, J., Cox, C. R., & Arndt, J. (2007). “Viewing” pregnancy as an existential threat: The effects of creatureliness on reactions to media depictions of the pregnant body. Media Psychology, 10, 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701375629.

Grieve, R., & Helmick, A. (2008). The influence of men’s self-objectification on the drive for muscularity: Self-esteem, body satisfaction and muscle dysmorphia. International Journal of Men’s Health, 7, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0703.288.

Grigoriadis, S., VonderPorten, E. H., Mamisashvili, L., Tomlinson, G., Dennis, C. L., Koren, G., … Ross, L. E. (2013). The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74, 321–341. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r07968.

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Johnston-Robledo, I., & Fred, V. (2008). Self-objectification and lower income pregnant women’s breastfeeding attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00293.x.

Johnston-Robledo, I., Wares, S., Fricker, J., & Pasek, L. (2007). Indecent exposure: Self-objectification and young women’s attitudes toward breastfeeding. Sex Roles, 56, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9194-4.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis (methodology in the social sciences). New York: Guilford Press.

Kukla, R. (2005). Pregnant bodies as public spaces. In S. Hardy & C. Wiedmer (Eds.), Motherhood and space (pp. 283–305). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-12103-5_16.

Lawrence, E., Barry, R. A., Brock, R. L., Bunde, M., Langer, A., Ro, E., … Dzankovic, S. (2011). The relationship quality interview: Evidence of reliability, convergent and divergent validity, and incremental utility. Psychological Assessment, 23, 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021096.

Lawrence, E., Brock, R. L., Barry, R. A., Langer, A., & Bunde, M. (2009). Assessing relationship quality: Development of an interview and implications for couple assessment and intervention. In E. Cuyler & M. Ackhart (Eds.), Psychology of relationships (pp. 173–191). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc..

Lawrence, E., Rothman, A. D., Cobb, R. J., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: Three eras of research. In M. S. Schulz, M. K. Pruett, P. K. Kerig, & R. D. Parkes (Eds.), Strengthening couple relationships for optimal child development: Lessons from research and intervention (pp. 97–114). https://doi.org/10.1037/12058-007.

Mahar, E. A., Webster, G. D., & Markey, P. M. (2020). Partner–objectification in romantic relationships: A dyadic approach. Personal Relationships, 27(1), 4-26. doi.org/10.1111/pere.12303

McKinley, N. M. (2006). The developmental and cultural contexts of objectified body consciousness: A longitudinal analysis of two cohorts of women. Developmental Psychology, 42, 679–687. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.679.

Mckinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2014). “Tell me i’m sexy . . . and otherwise valuable”: body valuation and relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 21, 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12018.

Micali, N., Simonoff, E., & Treasure, J. (2007). Risk of major adverse perinatal outcomes in women with eating disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.020768.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Morris, K. L., Goldenberg, J. L., & Heflick, N. A. (2014). Trio of terror (pregnancy, menstruation, and breastfeeding): An existential function of literal self-objectification among women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036493.

Morry, M. M., & Staska, S. L. (2001). Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087148.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x.

Oehlhof, M. E. W., Musher-Eizenman, D. R., Neufeld, J. M., & Hauser, J. C. (2009). Self-objectification and ideal body shape for men and women. Body Image, 6, 308–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.05.002.

Paulson, J. F., & Bazemore, S. D. (2010). Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 303, 1961–1969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.605.

Pearlstein, T. (2015). Depression during pregnancy. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 29, 754–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.004.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Prichard, I., & Tiggemann, M. (2005). Objectification in fitness centers: Self-objectification, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in aerobic instructors and aerobic participants. Sex Roles, 53, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-4270-0.

Ramsey, L. R., & Hoyt, T. (2015). The object of desire: How being objectified creates sexual pressure for women in heterosexual relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39, 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314544679.

Ramsey, L. R., Marotta, J. A., & Hoyt, T. (2017). Sexualized, objectified, but not satisfied: Enjoying sexualization relates to lower relationship satisfaction through perceived partner-objectification. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34, 258–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516631157.

Rauff, E. L., & Downs, D. S. (2011). Mediating effects of body image satisfaction on exercise behavior, depressive symptoms, and gestational weight gain in pregnancy. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42, 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-011-9300-2.

Roberts, T.-A., Calogero, R. M., & Gervais, S. J. (2018). Objectification theory: Continuing contributions to feminist psychology. In C. B. Travis, J. W. White, A. Rutherford, W. S. Williams, S. L. Cook, & K. F. Wyche (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology series. APA handbook of the psychology of women: History, theory, and battlegrounds (pp. 249–271). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Rubin, L. R., & Steinberg, J. R. (2011). Self-objectification and pregnancy: Are body functionality dimensions protective? Sex Roles, 65, 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9955-y.

Rust, J., & Golombuck, S. (1985). The golombok-rust inventory of sexual satisfaction (griss). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 63–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1985.tb01314.x.

Sáez, G., Riemer, A. R., Brock, R. L., & Gervais, S. J. (2019). Objectification in heterosexual romantic relationships: Examining relationship satisfaction of female objectification recipients and male objectifying perpetrators. Sex Roles, 81, 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0990-9.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136.

Silveira, M. L., Ertel, K. A., Dole, N., & Chasan-Taber, L. (2015). The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. Springer-Verlag Wien., 18, 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0525-0.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2002). A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 46, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020232714705.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2010). Body image and disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 63, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9794-2.

Stearns, C. A. (1999). Breastfeeding and the good maternal body. Gender & Society, 13, 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124399013003003.

Steer, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2008). The role of self-objectification in women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.3.205.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. (2004). Eating disorder prevention programs: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 206–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.206.

Strelan, P., & Hargreaves, D. (2005). Women who objectify other women: The vicious circle of objectification? Sex Roles, 52, 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3737-3.

Strelan, P., & Pagoudis, S. (2018). Birds of a feather flock together: The interpersonal process of objectification within intimate heterosexual relationships. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 79(1-2), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0851-y

Szymanski, D. M., Moffitt, L. B., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Sexual objectification of women: Advances to theory and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 6–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010378402.

Tiggemann, M., & Lynch, J. E. (2001). Body image across the life span in adult women: The role of self-objectification. Developmental Psychology, 37, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.243.

Tiggemann, M., & Williams, E. (2012). The role of self-objectification in disordered eating, depressed mood, and sexual functioning among women: A comprehensive test of objectification theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311420250.

Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2004). The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752925.

Tylka, T. L., & Hill, M. S. (2004). Objectification theory as it relates to disordered eating among college women. Sex Roles, 51, 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-0721-2.

Watson, D., O’Hara, M. W., Naragon-Gainey, K., Koffel, E., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., … Ruggero, C. J. (2012). Development and validation of new anxiety and bipolar symptom scales for an expanded version of the idas (the idas-ii). Assessment, 19, 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112449857.

Wiseman, M. C., & Moradi, B. (2010). Body image and eating disorder symptoms in sexual minority men: A test and extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018937.

Yonkers, K. A., Wisner, K. L., Stewart, D. E., Oberlander, T. F., Dell, D. L., Stotland, N., … Lockwood, C. (2009). The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the american psychiatric association and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31, 403–413..1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.003.

Zurbriggen, E. L., Ramsey, L. R., & Jaworski, B. K. (2011). Self- and partner-objectification in romantic relationships: associations with media consumption and relationship satisfaction. Sex Roles, 64, 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9933-4

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by several internal funding mechanisms awarded to PI Rebecca L. Brock from the UNL Department of Psychology, the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund, and the UNL Office of Research and Economic Development. We thank the families who participated in this research and the entire team of research assistants who contributed to various stages of the study. In particular, we thank Jennifer Blake and Kailee Groshans for project coordination, and Molly Franz and Michelle Haikalis for contributions to literature review and data preparation.

Funding

This research was funded by several internal funding mechanisms awarded to PI Rebecca L. Brock from the UNL Department of Psychology, the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund, and the UNL Office of Research and Economic Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This research involved human participants. Research was approved by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Institutional Review Board. IRB Approval #: 20151215700EP. Title: Family Development Project.

No animals were involved in this research.

Informed Consent

Participants completed written informed consent procedures at the beginning of the laboratory visit.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brock, R.L., Ramsdell, E.L., Sáez, G. et al. Perceived Humanization by Intimate Partners during Pregnancy Is Associated with fewer Depressive Symptoms, Less Body Dissatisfaction, and Greater Sexual Satisfaction through Reduced Self-Objectification. Sex Roles 84, 285–298 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01166-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01166-6