Abstract

Sexual objectification is one of most the common manifestations of discrimination against women in Western societies; however, few studies have examined objectification in the context of romantic relationships. The primary aim of the present research was to bring the study of objectification phenomena into the setting of heterosexual romantic relationships. The present set of studies examined the relation between sexual objectification and relationship satisfaction for both the sexual objectification recipient (Study 1) and the sexual objectification perpetrator (Study 2). The results of the first study with 206 U.S. undergraduate female students in committed romantic relationships replicated a previously identified negative association between feeling dehumanized by one’s partner and intimate relationship satisfaction. Moreover, this link was mediated by greater body dissatisfaction and decreased sexual satisfaction. The second study with 94 U.S. undergraduate male students in committed romantic relationships demonstrated a negative association between sexual objectification perpetration and relationship satisfaction. Furthermore, this negative relation was mediated by greater partner objectification and lower sexual satisfaction. Results of both studies demonstrated the effect of sexual objectification (as recipient or perpetrator) on global intimate relationship health. Additionally, the results highlight poor sexual satisfaction as a key dyadic mechanism linking objectification processes to intimate relationship outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I am at this moment, what I have always been to him: an object of beauty. He has never loved me as a woman. -- excerpt from Lady of the Rivers, Gregory (2011)

According to objectification theory, women are commonly viewed with a narrow focus on their body and appearance (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Although it is natural to observe others’ appearances, considering a woman’s appearance as capable of representing her and ignoring her humanity represents a sexually objectifying perspective (Bartky 1990). According to objectification theory, reoccurring experiences of objectification lead women to experience adverse mental health consequences (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). A plethora of studies have supported this basic tenet of objectification theory, revealing the pervasive nature of objectification within women’s lives and the resulting mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, sexual satisfaction; for reviews see Moradi and Huang 2008; Roberts et al. 2017).

Women commonly report experiencing objectifying gazes and appearance commentary from strangers and acquaintances and, as a result, research has focused primarily on the consequences of objectification from these types of perpetrators (Fairchild and Rudman 2008; Kozee et al. 2007; Vandenbosch and Eggermont 2012). Yet, the important role appearance-focus plays in maintaining intimate relationships (Feingold 1990) suggests that objectification may also occur within these relationships. A narrowed focus on a female partner’s appearance at the expense of considering her humanity may lead men to consider their partner less as a person and more as an object of beauty.

Because little work has attempted to understand women’s experiences of objectification when perpetrated by romantic partners (cf. Ramsey et al. 2017; Zurbriggen et al. 2011), in the current work we examined relationship consequences that occur for both heterosexual women when they are objectified by a male romantic partner and heterosexual men when they objectify their female romantic partner. More specifically, we explored two complementary models for female recipients (Study 1) and male perpetrators (Study 2) of sexual objectification, highlighting the importance of how sexual objectification (victimization or perpetration) undermines sexual satisfaction, which in turn, undermines relationship satisfaction more generally.

Interpersonal Sexual Objectification

Generally speaking, sexual objectification occurs when women are no longer thought of as human beings with their own thoughts, feelings, and desires, and instead they are reduced to their bodies, body parts or sexual functions for the pleasure of others (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Sexual objectification directed toward women from men occurs in everyday interactions through body gazes and appearance commentary (Kozee et al. 2007), with myriad consequences for both female recipients and male perceivers. Although men can also be objectified (Rohlinger 2002), research suggests that women are more likely than men are to be recipients of objectification (Davidson et al. 2013; Kozee et al. 2007) and that women experience more adverse consequences as a result of objectification. For example, relative to men, women show greater cognitive deficits (Gervais et al. 2011) and engage in more silencing behaviors (Saguy et al. 2010) following objectification.

At the same time, research has revealed that perpetrators see women more negatively following objectification. When men objectify women, they perceive women as less human, instead seeing them as similar to everyday objects (Bernard et al. 2012; Gervais et al. 2012) and animals (Vaes et al. 2011), as well as attributing them less mental capacity (Loughnan et al. 2013). These changes in perception due to objectification also influence the ways in which men interact with women by decreasing men’s empathy toward rape victims (Linz et al. 1988) and increasing proclivity toward sexually harassing behaviors (Galdi et al. 2014; Rudman and Mescher 2012).

Sexual Objectification in Romantic Contexts

Although research on women’s interpersonal sexual objectification has primarily focused on objectification occurring within interactions with male strangers or acquaintances, objectification can also occur within romantic relationships. Feminist scholars have long questioned the role that objectification plays within heterosexual intimate relationships (MacKinnon 1989; Nussbaum 1995). The potential for sexual objectification occurs with any body gaze or appearance comment in which the perpetrator sees the recipient as nothing more than a body (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Given the integral role physical attractiveness plays in relationships (Feingold 1990), appearance is commonly a focal point within intimate relationships. Although focusing on a partner’s appearance (e.g., through a body gaze or appearance compliment) may be a harmless occurrence within a heterosexual relationship, focusing on a partner’s appearance to the extent that her non-physical qualities are devalued (e.g., through chronic body surveillance) is a clear indicator of sexual objectification.

Research applying objectification theory to relationships suggests that heterosexual intimate relationships may be a particularly important context in which to consider sexual objectification because of the critical role romantic partners may play in mitigating or exacerbating appearance concerns (Meltzer and McNulty 2014; Overstreet et al. 2015; Wiederman 2000), as well as the broader impact on the relationship more generally (e.g., relationship satisfaction, Zurbriggen et al. 2011; relationship attachment, DeVille et al. 2015). Yet the relation between sexual objectification and romantic relationship satisfaction is ambiguous. On the one hand, feminist scholar Martha Nussbaum (1995) has theorized sexual objectification among partners as potentially healthy and a signal of intimacy, suggesting that romantic relationships are a unique context in which objectification is sometimes safe and perhaps even enjoyable. On the other hand, most objectification scholars (e.g., Bartky 1990; Langton 2009) have theorized that sexual objectification in romantic and sexual relationships is associated with uniformly adverse outcomes.

Empirical research has mostly supported the latter position that objectification occurring within heterosexual romantic contexts has detrimental effects on both men and women in the relationship. One primary finding from the limited research on objectification in relationships is that objectification is associated with lower relationship satisfaction (Zurbriggen et al. 2011). For instance, in an examination of objectified media consumption in couples, Zurbriggen and colleagues (Zurbriggen et al. 2011) revealed that greater consumption of objectifying media was indirectly related to decreased relationship satisfaction through partner and self-objectification. Partner objectification also was negatively related to male sexual satisfaction. Moreover, in recent studies examining objectification within relationships, objectification of one’s partner was related to decreased relationship quality (Ramsey et al. 2017; Strelan and Pagoudis 2018). Although previous work suggests that objectification is detrimental to relationship satisfaction, it remains unclear why objectification may undermine relationship satisfaction. The current study attempts to fill this gap by considering sexual satisfaction as a potential mediator in the relation between objectification and relationship satisfaction.

Objectification within relationships may be very damaging for women (Sanchez and Kiefer 2007; Steer and Tiggemann 2008). Sexual activity naturally involves partners focusing on each other’s bodies. Yet, when men concomitantly see their female partners as less human, women may be at increased risk for experiencing body dissatisfaction, laying the groundwork for sexual dissatisfaction. The present work builds on foundational work in this area by examining not only whether sexual objectification decreases relationship satisfaction (Zurbriggen et al. 2011), but also why objectification experiences may contribute to less relationship satisfaction due to decreased sexual satisfaction. We then provide preliminary evidence for this mechanism for women and men. Thus, the innovation of the current research is based on the integration of the previous negative outcomes identified in traditional objectification research (e.g., damaging body image and sexual dissatisfaction among women and objectification and sexual dissatisfaction among men) with a complementary examination of both male and female perspectives within the context of intimate relationships.

Women’s Perceptions of Humanity Ascriptions and Relationship Satisfaction

Turning first to women, we expected that feeling like one’s partner values you primarily for your physical attributes would be associated with less relationship satisfaction. Considering that women are socialized to prioritize interpersonal relationships (Mahalik et al. 2005) and that physical attraction is a key element of romantic relationships (Feingold 1990), it is not surprising that women might feel ambivalence towards partner objectification or even enjoy sexualization (Ramsey et al. 2017). Nonetheless, partner objectification still contributes to increased self-surveillance (Ramsey and Hoyt 2015), a risk factor for women’s well-being (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Further, non-physical attributes (e.g., being loyal, kind, successful, fun, trustworthy, sensitive, supportive, and humorous) are considered essential within intimate relationships (Fletcher et al. 1999) and to think that your partner is ignoring these qualities may lead women to believe that their partner is not seeing them as fully human, having an negative effect on relationship satisfaction (Meltzer and McNulty 2014).

Women’s sexual objectification leads to less human attribution (e.g., morality; Heflick and Goldenberg 2009) on behalf of perceivers. Thus, women who are sexually objectified by their partners may believe that their partners primarily value their body and appearance without consideration of their human attributes (Haslam et al. 2013; Heflick and Goldenberg 2009). Such beliefs regarding perceived humanization (or the lack thereof) from their partner may influence relationship satisfaction. Specifically, perceived dehumanization from a male partner should serve as a powerful cue to women that their partners are seeing them less as people and more as sexual objects, thereby undermining women’s relationship satisfaction.

Although a handful of studies have shown a link between partner objectification and relationship dissatisfaction, the mechanisms explaining this link are less clear and to our knowledge, there have been no studies that have directly examined the impact of perceived dehumanization (which presumably follows from feeling objectified) from a partner. We suggest that a process unfolds with perceived dehumanization by the male partner undermining women’s body satisfaction which, in turn, undermines their sexual satisfaction, which is associated with lower global relationship satisfaction. Although this process has not been explicitly tested, it is consistent with prior research supporting specific links within the larger pathway.

The way in which women feel their intimate partners perceive them may also affect the way in which they perceive themselves. In particular, when women feel they are being perceived as a sex object, and not as a whole person, women report increased body shame (Kozee et al. 2007). Within heterosexual romantic contexts, in which evaluations from intimate partners are important, sexual objectification can cause discrepancies between women’s perceptions of their actual and ideal bodies (Overstreet et al. 2015). Prior research shows that discrepancies between how one wants to look and how one actually looks result in body shame and body dissatisfaction (Stice et al. 1994; Thompson and Stice 2001). Most of this prior research, however, has focused on internalization of thin ideals from media exposure (Harper and Tiggemann 2008; Knauss et al. 2008; Myers and Crowther 2007), but we extended this research to relationship partners in the current work. Importantly, the influence of objectification (and presumably related dehumanization) is so powerful that research suggests simply anticipating an objectifying gaze increases women’s feelings of body shame (Calogero 2004), which is closely connected to body dissatisfaction. Thus, we expect that feeling as if one’s partner values one for one’s body, resulting in perceived dehumanization by one’s partner, may result in body dissatisfaction. Importantly, body mass index (BMI) has been identified as an important factor to consider within examinations of body satisfaction (Bucchianeri et al. 2013) and due to BMI’s predictive nature of body dissatisfaction (Tiggemann 2005) and relation to objectification experiences (Holland and Haslam 2013), we also controlled for BMI when examining the relation between women’s perceived dehumanization and their body dissatisfaction.

Although decreased body satisfaction is problematic in and of itself (Buser and Gibson 2017; Tiggemann 2003), we suggest that it may be negatively associated with relationship satisfaction by undermining women’s sexual satisfaction. One of the primary negative outcomes theorized to occur as a result of sexual objectification is sexual dysfunction (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), in which women’s objectifying experiences negatively impact their sexual enjoyment. In support of objectification theory, as women’s appearance concerns increase, their sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction decrease (Pujols et al. 2010). Women who have been objectified are less likely to act toward their sexual goals, and thereby are less likely to experience sexual satisfaction (Calogero and Thompson 2009). Consistent with our suggestion that body dissatisfaction, resulting from perceived dehumanization from partners, will be associated with sexual dissatisfaction, prior research shows that objectification from partners predicts greater body shame and lower sexual agency (Ramsey and Hoyt 2015). Our work extends these findings by considering body dissatisfaction and sexual satisfaction resulting from dehumanization by a male romantic partner.

Additionally, the effects of women’s decreased sexual satisfaction may be far reaching, in which feeling sexually unfulfilled undermines overall relationship satisfaction. Importantly, feelings of intimacy are directly related to relationship satisfaction (Greeff et al. 2001). Although sexual closeness is only one form of intimacy attained within romantic relationships, research has revealed the important role sexual satisfaction plays in determining relationship satisfaction. For instance, in longitudinal studies with romantic couples, women’s feelings of sexual satisfaction directly predict their global relationship satisfaction (Yeh et al. 2006) and relationship quality (Sprecher 2002). Research also has demonstrated the importance of sexual satisfaction in relationship satisfaction by revealing that sexual satisfaction can compensate for the negative effects of communication difficulties on relationships (Litzinger and Gordon 2005).

Although some feminist scholars argue that objectification is a natural part of romantic relationships and can therefore be considered enjoyable (Nussbaum 1995), most empirical research is consistent with our suggestion that men’s dehumanization of women within romantic relationships will be associated with women’s decreased relationship satisfaction. More specifically, we hypothesized that women’s perception of dehumanization from their partner would be associated with: less relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 1a), more body dissatisfaction (Hypothesis 1b), and less sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1c). Additionally, we hypothesized that more body dissatisfaction would be associated with less sexual satisfaction (hypothesis 1d) and less sexual satisfaction would be associated with less relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 1e). Finally, in addition to our hypotheses about bivariate associations, we predicted that a serial mediation model would fit the data. Specifically, we predicted that greater perceived partner dehumanization would be associated with more body dissatisfaction, which we expected to be associated with less sexual satisfaction which, in turn, would be associated with lower relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 1f). Importantly, because of the significant role women’s body size has in predicting women’s body dissatisfaction (Davison et al. 2000), we controlled for women’s BMI within our mediation model.

Men’s Perpetrators of Sexual Objectification and Relationship Satisfaction

Women’s experiences of objectification within romantic relationships are merely one side of the coin within a dyadic context; men who objectify their partners may also face relationship consequences. Men who perpetrate objectifying behaviors toward women in general (e.g., cat-calling, body gazes) can be thought of as viewing the world through an objectifying lens. Men’s perpetration of sexual objectification, for example, is positively associated with how important they perceive others’ observable physical appearance relative to non-observable attributes (e.g., competence, personality; Gervais et al. 2017; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005) and indirectly related to violence within sexual domains (Gervais et al. 2014; Rudman and Mescher 2012). The objectifying lens of men who see women as objects results from biased cognitive processing (Bernard et al. 2012; Gervais et al. 2011; Tyler et al. 2017) that may lead men to approach women who help them to satisfy their sexual goals (Gruenfeld et al. 2008) and, in some cases, it may lead men to establish romantic relationships with women. This previous research suggests that men who rely on an objectifying lens when perceiving women in their environment may also be more likely to perceive their romantic partners through the same lens relative to men who do not rely on an objectifying lens. This bias in perceiving women has been theorized to lead men to adopt an objectifying lens when viewing their potential female partners, consequently damaging men’s intimate relationships with women (Brooks 1995). Accordingly, we suggest that the more men report objectifying women in general, the more they will objectify their romantic partners in particular.

Although objectification occurring within a romantic relationship could appear to be an innocuous and natural component of a sexual relationship (Nussbaum 1995), men’s objectification of their romantic partners may negatively influence their own relationship satisfaction. Sexual attractiveness is an essential component of intimate relationships (Huston and Levinger 1978), but partner objectification occurs when a partner’s appearance is narrowly focused on—at the cost of attending to their needs and desires. In line with this distinction, research has demonstrated the importance of sexual attraction within relationships by revealing that men’s feelings of sexual attraction are positively associated with relationship satisfaction (Meltzer et al. 2014). However, expressing concerns about his partner’s appearance and treating her as an object (instead of a person) are behaviors associated with decreased relationship satisfaction (Sanchez et al. 2008), implying “that viewing one’s partner as an object is not good for one’s relationship” (Zurbriggen et al. 2011, pp. 459). Although attending to a partner’s sexual attractiveness may increase relationship satisfaction, focusing primarily on a partner’s appearance at the expense of considering her other attributes may decrease men’s relationship satisfaction.

These findings are consistent with theorizing on the centerfold syndrome (Brooks 1995)—a phenomenon suggesting that mere exposure to sexually objectifying media has a negative effect on men’s sexuality and capacity to establish intimate relationships with women. Consistently, exposure to objectifying media predicts men’s centerfold beliefs (e.g., sexual reductionism or non-relational sex; Wright and Tokunaga 2015), all of which are related to difficulties in establishing intimate relationships with women (Wright et al. 2017). Furthermore, when men focus exclusively on using a woman’s body as an object to give pleasure during sexual encounters, men report lower relationship satisfaction (Doran and Price 2014; Wright et al. 2017). Given these demonstrated associations between men’s objectification of relationship partners and decreased relationship satisfaction, our work extends these previous findings by considering why men’s partner objectification undermines relationship satisfaction.

In addition to sexual attractiveness, sexual satisfaction plays an integral role in relationship satisfaction, especially for men (Young et al. 1998). Similar to the ways in which experiencing objectification leads women to experience sexual dissatisfaction, men’s perpetration of objectification may lead to decreased sexual satisfaction. For instance, men’s exposure to media objectifying women’s bodies decreases men’s sexual satisfaction (Yucel and Gassanov 2010). Akin to the manner in which objectification experiences reduce women’s sexual satisfaction (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), men’s habitual focus on their partner’s appearance may detract from their ability to enjoy their sexual experiences in the moment. Consistently, Zurbriggen et al. (2011) found that men’s partner objectification was related to lower sexual satisfaction. Moreover, heterosexual men who objectified their partners were more likely to sexually pressure and coerce their female partners (Ramsey and Hoyt 2015), potentially impacting the quality and enjoyment of sexual experiences. Thus, we expected men’s increased partner objectification to be associated with decreased sexual satisfaction.

For men, adopting an objectifying lens of women may also indirectly affect their relationship satisfaction with their current partner through the effect of a persistent focus on their partner’s appearance and related decreases in sexual satisfaction. As Brooks (1995) suggested, men who objectify women may struggle to develop new intimate relationships with women because their objectifying lens decreases their sexual satisfaction (Zurbriggen et al. 2011) and, consequently, their relationship satisfaction (Zillmann and Bryant 1988). We extend prior research on the centerfold syndrome by examining men’s interpersonal objectification of other women (vs. exposure to objectifying media) as predictors of reduced sexual and relationship satisfaction. Given the importance of sexual satisfaction in determining relationship satisfaction (Young et al. 1998), decrements in sexual satisfaction that occur as a result of objectifying their partner may undermine relationship satisfaction. Therefore, we suggest that men’s general objectification of women will indirectly harm their relationship satisfaction through partner objectification and sexual satisfaction.

Although men may commonly adopt an objectifying lens of women in their environments, the current work attempts to reveal how this lens may harm men’s own romantic relationships. Specifically, we hypothesized that men’s objectification of women in general would be associated with more objectification of their intimate partners (Hypothesis 2a) and that (2b) men’s objectification of their partners would be associated with less relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 2b) as well as sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2c). Finally, in addition to our hypotheses about significant bivariate associations among the study variables, we predicted a serial mediation model. Specifically, we expect men’s objectification of women to be associated with increased partner objectification, which is associated with decreased sexual satisfaction, which, in turn, is associated with lower global relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 2d).

Overview and Aims

In this set of two studies, we aimed to expand upon previous work by examining the consequences of objectification within intimate relationships between men and women, as well as conceptually replicate the previous literature revealing links between sexual objectification and both relationship and sexual satisfaction (Ramsey et al. 2017; Zurbriggen et al. 2011) Given the common role of men as perpetrators and women as recipients of objectification, alongside previous findings demonstrating the heightened negative consequences for female targets, we took a two-sided approach to examining how objectification influences intimate relationships. In Study 1, we examined the consequences for women of perceived dehumanization from their partner (presumably resulting from men’s objectification), and in Study 2, we examined the consequences for men in relationships in which they objectify women. With both genders, we examined the consequences of objectification on relationships in terms of both sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Study 1

Method

Participants

A total of 240 female undergraduates at a large U.S. Midwestern university who reported being in a committed, intimate relationship completed the study. Of these women, 17 were excluded because they did not correctly answer 80% (4 of 5) of the attention checks (e.g., “If you are paying attention, please select 1 strongly disagree as the answer”). An additional 17 participants were excluded because they did not identify as heterosexual. The remaining 206 participants ranged in age from 17 to 32 years-old (M = 19.83, SD = 1.47). A majority of participants described themselves as Caucasian (Non-Hispanic; 184, 87.4%), followed by African American (7, 3.4%), Asian (6, 2.9%), Hispanic (8, 3.9%), and Other (5, 2.4%). To index relative body weight, we assessed participants’ body size through their BMI by dividing participants’ weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. Mean BMI across participants was 24.20 (just below overweight; SD = 5.34), ranging from 16.98 (underweight) to 53.88 (extreme obesity). Although BMI was assessed using self-report, previous work has identified self-report BMI data as having external validity (Kuczmarski et al. 2001).

Procedure and Measures

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to study recruitment. Undergraduate students taking introductory and upper level psychology courses were recruited using a psychology department participant pool. After providing informed consent, participants completed the study measures embedded within a larger series of questionnaires online.

Perceived Dehumanization

In the absence of an existing validated measure of the extent to which an individual perceives their relationship partner is ascribing them human attributes opposed to considering them nothing more than a body, we adopted one-item from a larger measure used by Meltzer and McNulty (2014). Specifically, we asked participants, “To what extent do you believe your relationship partner values you for your non-physical qualities (e.g., intelligence, fun, creativity, ambition, kindness, generosity, patience, career success, trustworthiness, ability to solve problems, humor, loyalty, and supportiveness)?,” using a 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely) Likert-type scale. Responses were reverse coded so that higher responses indicated lower perception of humanness attribution (i.e., greater perceived dehumanization) by one’s partner (M = 1.37, SD = .66).

Body Dissatisfaction

Participants completed the Body Dissatisfaction subscale from the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI; Forbush et al. 2013) as a measure of body dissatisfaction. This seven-item measure asks participants to rate the frequency with which they felt satisfied and dissatisfied with their body during the past 4 weeks (e.g., “I did not like how clothes fit the shape of my body”) using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Participants’ responses were averaged to create a composite in which higher scores indicate greater body dissatisfaction (M = 1.96, SD = 1.01). Consistent with previous use of this scale with a U.S. college student sample, which also demonstrated adequate convergent, divergent, and construct validity (Forbush et al. 2013), the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Sexual Satisfaction

Sexual satisfaction was measured with a single self-report item administered as part of the Relationship Quality Interview (RQI; Lawrence et al. 2011). Participants were instructed, “Thinking about recent interactions that you have with your partner, please rate how satisfied you were with the level of sexuality and sensuality in your relationship,” using a 1 (not at all satisfied) to 9 (extremely satisfied) scale. To obtain a score of sexual satisfaction that considered multiple facets of the sexual relationship, detailed descriptors were provided at each anchor on the scale [not at all satisfied/moderately satisfied/extremely satisfied] on the 9-point scale:

I was [NOT AT ALL/ MODERATELY/ EXTREMELY] satisfied. I was [dissatisfied/ somewhat satisfied/ extremely satisfied] with the frequency and quality of sexual activity in our relationship. [One or both of us experienced sexual difficulties/ No sexual difficulties occurred]. I was [dissatisfied/ moderately satisfied/ extremely satisfied] with the frequency and quality of sensual behaviors in my relationship (e.g., cuddling, massage).

Higher values indicated greater sexual satisfaction in the relationship (M = 7.53, SD = 1.88).

Relationship Satisfaction

As a measure of relationship satisfaction, participants completed the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI, Norton 1983). This six-item self-report questionnaire was designed to assess the essential goodness of a marriage; given not all participants in the present study were married, items referring to one’s marriage were modified to refer to one’s intimate relationship. For the first five items, participants were asked to indicate their agreement with statements, such as “We have a good relationship,” on a Likert scale from 1 (very strong disagreement) to 7 (very strong agreement). On the final item, participants were asked to rate their “overall level of happiness in the relationship” on a Likert-type scale from 1 (very unhappy) to 10 (perfectly happy). Responses were summed, with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction (M = 39.38, SD = 7.63). The internal consistency of the QMI in the current study (Cronbach’s α = .97) was similar to previous studies (e.g., α = .94, Graham et al. 2011).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables are shown in Table 1. Consistent with hypotheses, women’s perceived dehumanization from their partners was significantly related to their levels of both sexual and relationship satisfaction in the expected directions. Feeling dehumanized was negatively correlated with relationship satisfaction (supporting Hypothesis 1a), positively correlated with body dissatisfaction (Hypothesis 1b), and negatively correlated with sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1c). Also in line with hypotheses, women’s body dissatisfaction was negatively correlated with sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1d), whereas sexual satisfaction was positively correlated with relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 1e). Notably, the correlations indicate that all constructs, including sexual satisfaction and romantic relationship satisfaction, were sufficiently distinct to warrant investigating them as separate variables in the model; there were no multicollinearity concerns (rs < .70).

To examine the unique indirect effects of women’s perceived dehumanization from their partners on relationship satisfaction though body dissatisfaction and sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1f), we tested a serial mediation model using PROCESS (Version 2; Model 6; Hayes 2013). The degree to which women reported perceived dehumanization by their partners was entered as the predictor (X), relationship satisfaction was entered as the criterion (Y), and body dissatisfaction (M1) and sexual satisfaction (M2) were entered as the mediating variables. Following Fredrickson and colleagues’ (Fredrickson et al. 1998) suggestion of considering women’s body size, we included the continuous BMI as covariate in the model.

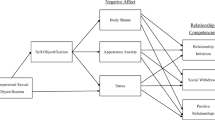

Following procedures recommended by Hayes (2013) for testing indirect effects with serial mediators, we used bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping to estimate the indirect effect. Bootstrapping maximizes power while minimizing Type I errors and provides an empirical approximation of sampling distributions of indirect effects to produce confidence intervals (CI) of estimates. If zero does not fall within the CI, one can conclude that an indirect effect is different from zero. Based on 10,000 bootstrap samples, the full indirect effect of X on Y via M1 and M2 was present, as indicated by 95% CIs that did not include 0. Consistent with Hypothesis 1f, controlling for BMI, women’s felt dehumanization from their partner was indirectly linked to lower relationship satisfaction through the effect of dehumanization on increased body dissatisfaction and decreased sexual satisfaction (B = −.09, SE = .07, 95% CI [−.32, −.01]). Specifically, greater dehumanization was associated with increased body dissatisfaction, which, in turn, was uniquely associated with decreased sexual satisfaction (controlling for dehumanization), which was uniquely related to global dissatisfaction in the relationship (controlling for dehumanization and body dissatisfaction) (see Fig. 1).

Notably, the distinct pathways through each of the mediators were not present; specifically, (a) the indirect effect of partner objectification on relationship satisfaction through body dissatisfaction (95% CI [−.69, .08]) and (b) the indirect effect of partner objectification on relationship satisfaction through sexual satisfaction (95% CI [−.98, .20]) were not significant. This pattern suggests that both mediators are essential for this pathway to unfold and that the association between body dissatisfaction and sexual satisfaction is a key feature of this process.

Study 2

Method

Participants

A total of 108 male undergraduates at a large U.S. Midwestern university who reported being in a committed, intimate relationship completed the study. Of these men, six were excluded from analysis for not having correctly answered the attention check questions (“If you are paying attention, please select 1 strongly disagree as the answer”). And an additional eight participants were excluded because they did not identify as heterosexual. The remaining 94 participants ranged in age from 17 to 30 years-old (M = 19.70, SD = 2.00). Regarding racial demographics, the majority described themselves as Caucasian (Non-Hispanic; 80, 85.1%), followed by African American (4, 4.3%), Asian (4, 4.3%), Hispanic (2, 2.1%), and 4 (4.3%) designated as Other.

Procedure and Measures

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to study recruitment. Identical to the first study, undergraduate students taking introductory and upper level psychology courses were recruited using a psychology department participant pool. After providing informed consent, participants completed the study surveys embedded within a larger series of questionnaires.

Objectification Perpetration

To assess the extent to which participants objectified women, participants completed the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale-Perpetration version (ISOS-P; Gervais et al. 2017). This 15-item scale asks men to report on the frequency with which they engage in body evaluation (e.g., “How often have you made inappropriate sexual comments about someone’s body?”) and unwanted sexual advances (e.g., “How often have you touched or fondled someone against her will?”), using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always). Participants’ responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating more frequent objectification perpetration of women (M = 1.84, SD = .45). Similar to administrations of the ISOS-P in other samples (α = .84–.90; Gervais et al. 2017), the ISOS-P demonstrated good internal consistency for the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .89). As the authors of the original scale demonstrated, ISOS-P has adequate construct validity being positively associated with other-objectification (Gervais et al. 2017).

Partner-Objectification

Men’s objectification specifically of their partners was assessed using a modified version of the surveillance subscale of McKinley and Hyde’s Objectified Body Consciousness scale (OBCS; McKinley and Hyde 1996; Zurbriggen et al. 2011). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they monitor their partner’s body (e.g., “I often think about whether the clothes my relationship partner is wearing makes her look good”) on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). Participants’ responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater objectification of their partner (M = 3.12, SD = .75). The adequate internal consistency found in our study (Cronbach’s α = .70) is similar to the previous use of this adapted measure (α = .67; Zurbriggen et al. 2011).

Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

As in Study 1, participants’ sexual satisfaction was measured with a single self-report item administered as part of the Relationship Quality Interview (RQI; Lawrence et al. 2011) using a 1 (not at all satisfied) to 9 (extremely satisfied) Likert type scale; the score was obtained considering multiple facets of the sexual relationship on the 9-point scale (M = 7.27;,SD = 2.03, for further information, see Study 1). Likewise, relationship satisfaction was measured with the QMI (Norton 1983) as it was in Study 1 (α = .95; M = 38.74, SD = 7.05). Item-level data were missing for one participant on the QMI scale and thus the total score was coded as missing. PROCESS uses pairwise deletion to address missing data.

Results

Table 2 presents correlational and descriptive statistics for all variables. Consistent with hypotheses, men’s perpetration of objectification of women in general was positively associated with objectifying their partners (supporting Hypothesis 2a), and partner-objectification was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 2b) as well as sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2c). The correlations among the study variables, including sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction, were significant but also less than .70; thus, there were no multicollinearity concerns.

We also hypothesized that the association between men’s general objectification perpetration and relationship satisfaction would be mediated by partner objectification and sexual satisfaction. As in Study 1, we tested this hypothesis using a serial mediation model using PROCESS (Version 2, Model 6; Hayes 2013) with objectification perpetration entered as predictor (X), relationship satisfaction entered as the criterion (Y), and partner objectification (M1) and sexual satisfaction (M2) entered as mediating variables. Following the same bootstrapping procedure as in Study 1, significance of indirect paths was assessed using 95% bias corrected and accelerated bootstrapping to estimate the indirect effect.

There was evidence of the full serial mediation effect (supporting Hypothesis 2d). Specifically, men’s objectification perpetration was indirectly associated with (lower) relationship satisfaction via partner objectification and sexual satisfaction (B = −.58, SE = .38, 95% CI [−1.79, −.11]). That is, greater objectification perpetration (in general) was associated with greater partner objectification, which in turn, was associated with lower sexual satisfaction (controlling for objectification perpetration in general), which subsequently, was associated with lower global relationship satisfaction (controlling for both forms of objectification) (see Fig. 2).

Serial mediation model depicting indirect effect of objectification perpetration and relationship satisfaction through partner objectification and sexual satisfaction for men in study 2. Unstandardized beta coefficients reported, with standard errors within parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Moreover, there was a significant negative indirect effect on objectification perpetration on relationship satisfaction through partner objectification, controlling for sexual satisfaction (B = −1.88, SE = .97, 95% CI [−4.28, −.32]). This relationship suggests that objectifying one’s partner might undermine relationship satisfaction though other mechanisms apart from sexual satisfaction. There was no evidence of a unique indirect effect of objectification perpetration on relationship satisfaction through sexual satisfaction (separate from partner objectification) (B = −.24, SE = .62, 95% CI [−1.75, .76]). Thus, partner objectification appears to be a key link in the pathway through which objectification perpetration ultimately is connected to relationship satisfaction by undermining sexual satisfaction.

Discussion

The purpose of the present work was to examine the consequences of sexual objectification as it occurs within intimate relationships. The present set of two studies provides an integrative dual-perspective of the objectification phenomenon within heterosexual romantic relationships, showing that sexual satisfaction plays a crucial explicatory role on the link between objectification and lower relationship satisfaction for both women and men. In addition, our findings replicate those of the scant literature that have explored objectification within romantic relationships (Ramsey et al. 2017; Zurbriggen et al. 2011). Although the majority of research conducted on the phenomenon of objectification has examined objectification from an intrapersonal perspective (for a review see Moradi and Huang 2008), our work extends a growing literature considering the interpersonal side of objectification, particularly in the context of romantic relationships (e.g., Ramsey et al. 2017; Ramsey and Hoyt 2015; Zurbriggen et al. 2011).

Our findings revealed that for women, thinking your partner perceives you as less human is associated with decreased relationship (Hypothesis 1a), body (Hypothesis 1b), and sexual (Hypothesis 1c) satisfaction. Furthermore, increases in body dissatisfaction were associated with decreases in sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1d), and decreased sexual satisfaction was associated with decreased relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 1e). These bivariate associations are consistent with objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), as well as empirical findings revealing the negative impact of objectification on women’s well-being. In particular, these findings support work revealing the negative association between feeling objectified by one’s partner on women’s sexual and relationship satisfaction (Meltzer and McNulty 2014; Ramsey, Marotta & Hoyt, 2017; Ramsey and Hoyt 2015). Conceptual replication allows overcoming the problem of measurement errors (Fisher 1992; Millsap and Maydeu-Olivares 2009). Following Earp and Trafimow (2015), who claim that conceptual replication validates the underlying phenomenon, the present findings corroborate the negative relation of sexual objectification with relationship satisfaction.

Extending prior research demonstrating the role of partner objectification in relational outcomes, we tested an integrated serial mediation model that accounts for both body dissatisfaction (among women)/partner-objectification (among men) and sexual satisfaction as mechanisms explaining this process. Results indicate that the association between women’s perceptions of dehumanization from their partner and their relationship satisfaction was mediated by women’s body and sexual satisfaction, controlling for BMI (Hypothesis 1f). Indeed, only the full serial mechanism was supported: Perceived partner dehumanization undermined body satisfaction, which decreased sexual satisfaction, which in turn was linked to lower relationship satisfaction. Thus, the current findings expand upon previous research demonstrating a significant correlation between women’s feelings of being objectified and thereby dehumanized by their partner, with body, sexual, and relationship satisfaction Friedman et al. 1999; Ramsey and Hoyt 2015) by explicating the mechanism ultimately linking perceived partner objectification and dehumanization to relationship satisfaction. Notably, our results contradict propositions made by feminist scholar Nussbaum (1995) regarding the possibility of healthy objectification occurring within relationships, but also help to explain why partner objectification might eventually undermine the health of one’s intimate relationship—that is, by undermining sexual satisfaction as a result of body dissatisfaction.

Although the full serial mediation effect was significant for women, alternative models must be explored in future studies. In particular, next studies should explore gender ideologies as potential alternative mechanisms of the link between objectification and relationship satisfaction. For example, benevolent sexist attitudes have been linked to the objectification phenomenon (Calogero and Jost 2011; Swami and Voracek 2013), to lower relationship satisfaction (Hammond and Overall 2013), and to body dissatisfaction (Swami et al. 2010). Moreover, benevolent sexism manifestations are perceived as subtle as sexual objectification manifestations (Riemer et al. 2014), given that both phenomena are closely related in a romantic relationship context. Thus, sexist ideologies like benevolent sexism may explain, in part, the link between objectification and relationship satisfaction. However, to perceive partner dehumanization is expected to result in more severe consequences than to perceive partner benevolent sexist ideology because such ideology promotes women’s protection because of its feminine-sensitive qualities (Glick and Fiske 1996) which is expected to differ from perceiving dehumanization which promotes manifestations of violence against women (Rudman and Mescher 2012).

In Study 2, our findings revealed that men’s objectification of women (external to the intimate relationship) was associated with their objectification of their intimate partner (Hypothesis 2a). Additionally, men’s objectification of their partner was associated with lower levels of relationship (Hypothesis 2b) and sexual (Hypothesis 2c) satisfaction. Our finding that men’s objectification of their partner was related to decreased relationship satisfaction supports Zurbriggen and colleague’s (Zurbriggen et al. 2011) findings that demonstrated the detrimental effect of consuming objectifying media on relationship satisfaction through partner objectification.

In line with previous research, we did not find a significant association between men’s general objectification of women and relationship satisfaction (Bareket et al. 2018). However, our results revealed that for men, perceiving women through an objectifying lens indirectly led to decreased relationship satisfaction through influencing how their partner was perceived as a sexual object and their sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2d). That is, men who generally engaged in greater objectification were also more likely to objectify their partners; this, in turn, undermined their sexual satisfaction, which was associated with lower levels of global relationship satisfaction. Further, the indirect effect of general objectification on relationship satisfaction via partner objectification (excluding sexual satisfaction) was significant, suggesting that objectifying one’s partner may undermine relationship satisfaction through other mechanisms than just the quality of the sexual relationship (e.g., perhaps decreasing trust/intimacy, undermining respect in the relationship). For example, previous research has related exposure to objectified media to behaviors that undermine healthy relationships, such as sex outside of relationships (Wright and Tokunaga 2015) or having an affair (Zillmann and Bryant 1988). Moreover, Zurbriggen and colleagues (Zurbriggen et al. 2011) have also suggested self-objectification as a possible alternative mechanism, implying that perceiving one’s partner as an object may also increase objectifying views of the self, adversely affecting the perceiver’s mental health and intimate relationships. Future research should explore this possibility. Importantly, objectification was not associated with relationship satisfaction through sexual satisfaction when partner objectification was excluded from the pathway; thus, partner objectification appears to be essential for objectification to undermine sexual satisfaction and, subsequently, relationship satisfaction.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although previous work studying objectification within relationship contexts has examined objectification felt by single individuals (Overstreet et al. 2015; Zurbriggen et al. 2011), the strength of the current work is our use of a sample of women and men currently in a self-defined committed relationship. Yet, the current studies focused solely on one side of the relationship (women in Study 1 and men in Study 2) instead of examining couples’ perceptions simultaneously. Because both studies relied upon correlational mediational analyses, caution also is needed for causal interpretation of the data. For example, the hypothesized relation found between men’s sexual objectification perpetration of women and objectification of their partner does not allow us to conclude that perpetration generally leads to objectification of one’s partner because the direction of the association cannot be determined. Due to this limitation, future research would benefit from experiments involving both sides of couples in which causal mechanisms could be explored.

Furthermore, the current work may be limited in the narrow way in which men’s and women’s perspectives are considered. According to objectification theory, society places an emphasis on the importance of women’s bodies and appearance determining women’s worth, with men’s gazes being the most common form of evaluation (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Empirical work supports this notion, revealing that men commonly objectify women (Strelan and Hargreaves 2005), that women are more frequent targets of objectification than men are (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), and that experiencing objectification results in more detrimental consequences for women than for men (Roberts and Gettman 2004). Furthermore, research suggests women play a complementary role in the cycle of objectification when interpersonal experiences of objectification lead women to self-objectify (Strelan and Hargreaves 2005). In the current work, therefore, we focused on women’s experiences of relationship objectification from a recipient’s perspective and on men’s experiences from a perceiver perspective. Although research supports, and often relies upon, a perspective in which women are considered recipients and men are considered perpetrators, this framing is another potential limitation of the current work. In future work examining the role of objectification within intimate relationships, consideration of women as perpetrators and men as recipients may further illuminate this complex phenomenon and shed light on whether and how objectification influences relationship satisfaction in both mixed-sex and same-sex relationships.

A final limitation of our work is that participants recruited in both studies were college men and women. Despite our inclusion criteria of being in a committed relationship, based on the participants’ age (mdnmen = 19; mdnwomen = 20), it is likely that many of the college student participants were in short-term relationships. Therefore, caution must be taken in generalizing the results young adults not in college and to long-term relationships. Although some of the same mechanisms may be at play, future studies should include individuals within long-term committed relationships.

Practice Implications

Although little work has attempted to understand how perpetrating objectification affects male perceivers, our findings are in line with feminist theorists who suggest that although women may be the common recipients of objectification, these experiences can be problematic for both men and women in different, but complementary ways (Brooks 1995; MacKinnon 1989). Men’s objectification of women in general, and their female relationship partner specifically, may have direct negative consequences for men by undermining their own relationship satisfaction. Perhaps more insidiously, it may also have indirect negative consequences for women by decreasing their female partner’s satisfaction in the relationship as well.

Generally speaking, our results revealed that sexual satisfaction played an important role in the association between objectification and relationship satisfaction. For a woman specifically, feeling dehumanized by her partner increases body dissatisfaction and decreases sexual satisfaction, in turn decreasing relationship satisfaction. Importantly, because sexual encounters involve partners focusing on each other’s bodies, increased body dissatisfaction and sexual dysfunction may commonly ensue (Sanchez and Kiefer 2007; Steer and Tiggemann 2008), ultimately affecting women’s sexual satisfaction and, consequently, their relationship satisfaction (Byers 2005).

Through an examination of the male perceiver’s perspective, the current work reveals that men’s perpetration of objectification of women generally predicts objectification of their intimate partner. Sexually objectifying perceptions commonly manifest as interpersonal behaviors in which men treat women as sex objects rather than as people (Gervais et al. 2017). Men’s objectifying lens toward their partners predicted difficulties treating their current partner as an equal person, instead focusing on their partner’s appearance. These findings are in line with previous work (Gervais et al. 2017), which revealed the link between sexual objectification perpetration and hostile sexism—an ideology that not only legitimizes women’s lower status, but also is negatively related with relationship satisfaction (Hammond and Overall 2013). The current work suggests that interventions aimed at reducing men’s reliance on an objectifying lens when viewing women generally may positively impact not only their general relations with women, but also their specific intimate relationships.

The results of the present study have implications for objectification theory and contemporary models of relationship satisfaction and stability (e.g., the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model; Karney and Bradbury 1995). Whereas the original articulation of objectification theory predicts adverse consequences for women’s well-being (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), the present findings demonstrate that the negative consequences of sexual objectification also extend to the health of intimate relationships. Thus, research aimed at understanding the complex pathways of risk leading to intimate relationship discord and instability might be enhanced by (a) examining how sexual objectification perpetration by men occurring outside their intimate relationships might set the stage for objectification within their relationships (i.e., partner objectification) and (b) identifying the various pathways through which objectification processes ultimately are related with lower relationship satisfaction by isolating intrapersonal (women’s self-objectification) and dyadic (sexual quality) mechanisms.

Moreover, the present findings may have practical implications for couples’ counselling. Our set of studies indicated that perceived partner dehumanization in women or perpetrated partner objectification in men is the antecedent of relationship dissatisfaction. Not only is empathy negatively associated with sexual objectification (Cogoni et al. 2018), but also perceived empathy is positively associated with relationship satisfaction (Cramer and Jowett 2010). Thus, the enhancement of empathy toward the female partner, which means focusing on her emotional and subjective states (inconsistent with objectification), might be a valuable strategy to increase relationship satisfaction in both members of the couple.

Conclusion

Together our two studies demonstrate the importance of applying tenants of objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997) to interpersonal relationships. Within intimate relationships in particular, physical attraction plays a significant role to the extent that women are perceived by men as an object of beauty, instead of being loved as a woman. The current work points to the various ways in which objectification can pervade both men’s and women’s lives, in particular within intimate relationships.

References

Bareket, O., Kahalon, R., Shnabel, N., & Glick, P. (2018). The Madonna-whore dichotomy: Men who perceive women's nurturance and sexuality as mutually exclusive endorse patriarchy and show lower relationship satisfaction. Sex Roles, 79(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0895-7.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Psychology Press.

Bernard, P., Gervais, S. J., Allen, J., Campomizzi, S., & Klein, O. (2012). Integrating sexual objectification with object versus person recognition: The sexualized-body-inversion hypothesis. Psychological Science, 23(5), 469–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434748.

Brooks, G. R. (1995). The centerfold syndrome: How men can overcome objectification and achieve intimacy with women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2017.1352277.

Bucchianeri, M. M., Arikian, A. J., Hannan, P. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.001.

Buser, J. K., & Gibson, S. (2017). Protecting women from the negative effects of body dissatisfaction: The role of differentiation of self. Women & Therapy, 41(3–4), 406–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2017.1352277.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552264.

Calogero, R. M. (2004). A test of objectification theory: The effect of the male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00118.x.

Calogero, R. M., & Jost, J. T. (2011). Self-subjugation among women: Exposure to sexist ideology, self-objectification, and the protective function of the need to avoid closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021864.

Calogero, R. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Potential implications of the objectification of women’s bodies for women’s sexual satisfaction. Body Image, 6, 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.01.001.

Cogoni, C., Carnaghi, A., & Silani, G. (2018). Reduced empathic responses for sexually objectified women: An fMRI investigation. Cortex, 99, 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.11.020.

Cramer, D., & Jowett, S. (2010). Perceived empathy, accurate empathy and relationship satisfaction in heterosexual couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509348384.

Davidson, M. M., Gervais, S. J., Canivez, G. L., & Cole, B. P. (2013). A psychometric examination of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale among college men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032075.

Davison, K. K., Markey, C. N., & Birch, L. L. (2000). Etiology of body dissatisfaction and weight concerns among 5-year-old girls. Appetite, 35(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1006/appe.2000.0349.

DeVille, D. C., Ellmo, F. I., Horton, W. A., & Erchull, M. J. (2015). The role of romantic attachment in women’s experiences of body surveillance and body shame. Gender Issues, 32(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-015-9136-3.

Doran, K., & Price, J. (2014). Pornography and marriage. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(4), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9391-6.

Earp, B. D., & Trafimow, D. (2015). Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(621), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00621.

Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21(3), 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0.

Feingold, A. (1990). Gender differences in effects of physical attractiveness on romantic attraction: A comparison across five research paradigms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.981.

Fisher, R. A. (1992). Statistical methods for research workers. In S. Kotz & N. L. Johnson (Eds.), Breakthroughs in statistics (pp. 66–70). New York: Springer.

Fletcher, G. J., Simpson, J. A., Thomas, G., & Giles, L. (1999). Ideals in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.72.

Forbush, K. T., Wildes, J. E., Pollack, L. O., Dunbar, D., Luo, J., Patterson, K., ... Bright, A. (2013). Development and validation of the eating pathology symptoms inventory (EPSI). Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 859–878. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032639.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T. A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.269.

Friedman, M. A., Dixon, A. E., Brownell, K. D., Whisman, M. A., & Wilfley, D. E. (1999). Marital status, marital satisfaction, and body image dissatisfaction. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26(1), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199907)26:1<81::AID-EAT10>3.0.CO;2-V.

Galdi, S., Maass, A., & Cadinu, M. (2014). Objectifying media: Their effect on gender role norms and sexual harassment of women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313515185.

Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., & Allen, J. (2011). When what you see is what you get: The consequences of the objectifying gaze for women and men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310386121.

Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., Förster, J., Maass, A., & Suitner, C. (2012). Seeing women as objects: The sexual body part recognition bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1890.

Gervais, S. J., DiLillo, D., & McChargue, D. (2014). Understanding the link between men’s alcohol use and sexual violence perpetration: The mediating role of sexual objectification. Psychology of Violence, 4(2), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033840.

Gervais, S. J., Davidson, M. M., Styck, K., Canivez, G., & DiLillo, D. (2017). The development and psychometric properties of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale-perpetration version. Psychology of Violence, 8(5), 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000148.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315187280.

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022441.

Greeff, P., Hildegarde, L., & Malherbe, A. (2001). Intimacy and marital satisfaction in spouses. Journal of Sex &Marital Therapy, 27(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262301750257100.

Gregory, P. (2011). Lady of the rivers. New York: Touchstone.

Gruenfeld, D. H., Inesi, M. E., Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Power and the objectification of social targets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.111.

Hammond, M. D., & Overall, N. C. (2013). Men’s hostile sexism and biased perceptions of intimate partners: Fostering dissatisfaction and negative behavior in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(12), 1585–1599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499026.

Harper, B., & Tiggemann, M. (2008). The effect of thin ideal media images on women’s self-objectification, mood, and body image. Sex Roles, 58(9–10), 649–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317743019.

Haslam, N., Loughnan, S., & Holland, E. (2013). The psychology of humanness. In S. J. Gervais (Ed.), Objectification and (de) humanization (pp. 25–51). New York: Springer.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Heflick, N. A., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2009). Objectifying Sarah Palin: Evidence that objectification causes women to be perceived as less competent and less fully human. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 598–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.008.

Holland, E., & Haslam, N. (2013). Worth the weight: The objectification of overweight versus thin targets. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312474800.

Huston, T. L., & Levinger, G. (1978). Interpersonal attraction and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 29(1), 115–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000555.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3.

Knauss, C., Paxton, S. J., & Alsaker, F. D. (2008). Body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: Objectified body consciousness, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media. Sex Roles, 59(9–10), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9474-7.

Kozee, H. B., Tylka, T. L., Augustus-Horvath, C. L., & Denchik, A. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00351.x.

Kuczmarski, M. F., Kuczmarski, R. J., & Najjar, M. (2001). Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: Findings from the third National Health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 101(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00008-6.

Langton, R. (2009). Sexual solipsism: Philosophical essays on pornography and objectification. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lawrence, E., Barry, R. A., Brock, R. L., Bunde, M., Langer, A., Ro, E., ... Dzankovic, S. (2011). The relationship quality interview: Evidence of reliability, convergent and divergent validity, and incremental utility. Psychological Assessment, 23, 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021096.

Linz, D. G., Donnerstein, E., & Penrod, S. (1988). Effects of long-term exposure to violent and sexually degrading depictions of women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.758.

Litzinger, S., & Gordon, K. C. (2005). Exploring relationships among communication, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 31(5), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230591006719.

Loughnan, S., Pina, A., Vasquez, E. A., & Puvia, E. (2013). Sexual objectification increases rape victim blame and decreases perceived suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313485718.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1989). Sexuality, pornography, and method: Pleasure under patriarchy. Ethics, 99(2), 314–346. https://doi.org/10.1086/293068.

Mahalik, J. R., Morray, E. B., Coonerty-Femiano, A., Ludlow, L. H., Slattery, S. M., & Smiler, A. (2005). Development of the conformity to feminine norms inventory. Sex Roles, 52(7–8), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3709-7.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(2), 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2014). “Tell me I'm sexy... And otherwise valuable”: Body valuation and relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 21(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12018.

Meltzer, A. L., McNulty, J. K., Jackson, G., & Karney, B. R. (2014). Sex differences in the implications of partner physical attractiveness for the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034424.

Millsap, R. E., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2009). The SAGE handbook of quantitative methods in psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H. (2007). Sociocultural pressures, thin-ideal internalization, self-objectification, and body dissatisfaction: Could feminist beliefs be a moderating factor? Body Image, 4(3), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.001.

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/351302.

Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291.

Overstreet, N. M., Quinn, D. M., & Marsh, K. L. (2015). Objectification in virtual romantic contexts: Perceived discrepancies between self and partner ideals differentially affect body consciousness in women and men. Sex Roles, 73(9–10), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9933-4.

Pujols, Y., Meston, C. M., & Seal, B. N. (2010). The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 905–916. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01604.x.

Ramsey, L. R., & Hoyt, T. (2015). The object of desire: How being objectified creates sexual pressure for women in heterosexual relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314544679.

Ramsey, L. R., Marotta, J. A., & Hoyt, T. (2017). Sexualized, objectified, but not satisfied: Enjoying sexualization relates to lower relationship satisfaction through perceived partner-objectification. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(2), 258–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516631157.

Riemer, A., Chaudoir, S., & Earnshaw, V. (2014). What looks like sexism and why? The effect of comment type and perpetrator type on women's perceptions of sexism. The Journal of General Psychology, 141(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2014.907769.

Roberts, T. A., & Gettman, J. Y. (2004). Mere exposure: Gender differences in the negative effects of priming a state of self-objectification. Sex Roles, 51(1–2), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000032306.20462.22.

Roberts, T. A., Calogero, R. M., & Gervais, S. (2017). Objectification theory: Continuing contributions to feminist psychology. In C. B. Travis, J. W. White, A. Rutherford, W. S. Williams, S. L. Cook, et al. (Eds.), APA handbook of the psychology of women: History, theory, and battlegrounds (pp. 249–271). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rohlinger, D. A. (2002). Eroticizing men: Cultural influences on advertising and male objectification. Sex Roles, 46(3–4), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016575909173.

Rudman, L. A., & Mescher, K. (2012). Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212436401.

Saguy, T., Quinn, D. M., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2010). Interacting like a body: Objectification can lead women to narrow their presence in social interactions. Psychological Science, 21(2), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609357751.

Sanchez, D. T., & Kiefer, A. K. (2007). Body concerns in and out of the bedroom: Implications for sexual pleasure and problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(6), 808–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9205-0.

Sanchez, D. T., Good, J. J., Kwang, T., & Saltzman, E. (2008). When finding a mate feels urgent: Why relationship contingency predicts men’s and women’s body shame. Social Psychology, 39, 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335.39.2.90.

Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552141.

Steer, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2008). The role of self-objectification in women's sexual functioning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(3), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.3.205.

Stice, E., Schupak-Neuberg, E., Shaw, H. E., & Stein, R. I. (1994). Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(4), 836–840. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.103.4.836.

Strelan, P., & Hargreaves, D. (2005). Women who objectify other women: The vicious circle of objectification? Sex Roles, 52, 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3737-3.

Strelan, P., & Pagoudis, S. (2018). Birds of a feather flock together: The interpersonal process of objectification within intimate heterosexual relationships. Sex Roles, 79(1–2), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0851-y.

Swami, V., & Voracek, M. (2013). Associations among men's sexist attitudes, objectification of women, and their own drive for muscularity. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028437.

Swami, V., Coles, R., Wilson, E., Salem, N., Wyrozumska, K., & Furnham, A. (2010). Oppressive beliefs at play: Associations among beauty ideals and practices and individual differences in sexism, objectification of others, and media exposure. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01582.x.

Thompson, J. K., & Stice, E. (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00144.

Tiggemann, M. (2003). Media exposure, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Television and magazines are not the same! European Eating Disorders Review, 11(5), 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.502.

Tiggemann, M. (2005). Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self-esteem: Prospective findings. Body Image, 2(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.006.

Tyler, J., Calogero, R. M., & Adams, K. (2017). Perpetuation of sexual objectification: The role of resource depletion. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12157s.

Vaes, J., Paladino, M. P., & Puvia, E. (2011). Are sexualized females complete human beings? Why males and females dehumanize sexually objectified women. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 774–785. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.824.

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2012). Understanding sexual objectification: A comprehensive approach toward media exposure and girls' internalization of beauty ideals, self-objectification, and body surveillance. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01667.x.

Wiederman, M. W. (2000). Women's body image self-consciousness during physical intimacy with a partner. Journal of Sex Research, 37(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490009552021.

Wright, P. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2015). Activating the centerfold syndrome: Recency of exposure, sexual explicitness, past exposure to objectifying media. Communication Research, 42(6), 864–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213509668.