Abstract

Drawing on a life course perspective and data gathered during three developmental periods—the transition to adulthood (age 25; n = 168), young adulthood (age 32; n = 337), and midlife (age 43; n = 309), we explored patterns of division of household labour among Canadian men and women. We also investigated associations among housework responsibility and variables representing time availability (i.e., work hours), relative resource (i.e., earning a greater share of income in a relationship), and gender constructionist perspectives (i.e., marital status and raising children) at three life course stages. Results indicated women performed more housework than men at all ages. Regression analyses revealed housework responsibility was most reliably predicted by relative income and gender at age 25; work hours and raising children at age 32; and work hours, relative income, and gender at age 43. Gender moderated the influence of raising children at age 32. Overall, the relative resource perspective was supported during the transition to adulthood and in midlife, the time availability perspective was supported in young adulthood and in midlife, and certain elements of the gender constructionist perspective were supported at all life stages. The present study contributes to the division of household labour literature by disentangling the predictive power of time, resource, and gender perspectives on housework at distinct life stages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Considerable change in heterosexual couples’ division of household labour has occurred since the mid-twentieth century, with men doing more and women doing less housework than in the past (Bianchi et al. 2000). Despite the narrowing gender gap in housework, women continue to perform the bulk of this labour (Bianchi et al. 2012). These macro-level housework patterns, however, may obscure more subtle variations in partners’ division of labour that coincide with changing family and work norms, responsibilities, and experiences during different developmental stages throughout the life course. Indeed, results from cross-sectional (Rexroat and Shehan 1987), cross-cohort (Bianchi et al. 2000), and longitudinal (Artis and Pavalko 2003; Lam et al. 2012) studies demonstrate associations between partners’ housework responsibilities and important age-graded developmental experiences (e.g., securing employment, having children). As such, competing theories that offer pragmatic, economic, and gender-based explanations for how partners divvy up household labour may be more or less useful depending on stage in the life course. Yet much of the literature on the division of household labour excludes theoretically relevant predictors of housework responsibility (e.g., gender relations; Lam et al. 2012) or explores the aggregate contributions of housework predictors in a combined sample of age-diverse participants (e.g., Bianchi et al. 2000).

Drawing on a life course perspective (Elder 1994) and data from participants in the Edmonton Transitions Study who were married or cohabiting during the transition to adulthood (age 25; n = 168), young adulthood (age 32; n = 337), or midlife (age 43; n = 309), the present study (a) compares men’s and women’s division of household labour at different life stages and (b) explores associations between housework responsibility and theoretically relevant predictor variables (i.e., respondent’s work hours, higher relative income compared to partner, and marital status and raising children) at these three stages in the life course. Although the participants are from a single longitudinal study, the data at each life course stage are treated as though they are cross-sectional due to differential measurement in some waves and the inability to track partnership changes throughout the study. In addition, the participants for the current analyses were selected because they have intimate partners, but those partners are not in the present study.

Theoretical Framework

Our study is grounded in a life course meta-theoretical approach to individual development, which emphasizes the salience of social conditions in shaping the way lives unfold over time (Dannefer 1984; Elder 1994). According to this perspective, human development is situated within three intersecting temporal dimensions: chronological age, interpersonal transitions, and sociohistorical position (Bengston and Allen 1993). Individuals’ behaviours are informed not only by their own biological development, but also by the work and family responsibilities they negotiate with their intimate partners as well as the broader social norms that govern appropriate role ordering and duration (Elder 1994). As such, individuals face unique challenges and opportunities at different stages in the life course based on changing age-graded, family, and sociocultural demands. The way people organize their daily lives at distinct points in time (e.g., young adulthood, midlife) to accomplish relevant developmental tasks is, therefore, expected to show considerable diversity (Elder et al. 2003). At the same time, individuals must also maintain some level of consistency in their intrapersonal characteristics and interpersonal relations to manage life’s ebbs and flows (Bengston and Allen 1993). A life course perspective highlights how individual development and family dynamics are simultaneously characterized by forces of change and continuity over time.

Given its focus on how individuals organize their lives at various ages and during transitional experiences, a life course perspective stresses the need for research that examines behavioural phenomena at several stages in individuals’ lives. Such an approach is well-suited to disentangling if and how the division of household labour differs depending on whether an individual is in the transition to adulthood (age 25), in young adulthood (age 32), or in midlife (age 43)—the primary goal of the present study. Moreover, a life course paradigm encourages researchers to be sensitive to how individual characteristics and interpersonal dynamics may vary over time, while others may remain relatively consistent. Housework responsibility at different life stages could demonstrate strong variations alongside fluctuations in family roles and social contexts, but housework routines could also be established early in a relationship and become an enduring norm that structures partners’ behaviour independent of age. Finally, the life course emphasis on relational and sociocultural environments influencing individual behaviour motivates a comprehensive inclusion of personal (i.e., work hours), interpersonal (i.e., partners’ relative incomes), and sociodemographic (i.e., gender, marital, and parental status) predictors of the division of household labour.

Division of Household Labour across the Life Course

In line with a life course paradigm, division of household labour patterns from the past few decades might be best described as featuring substantial change and remarkable continuity. A large body of literature demonstrates that women continue to perform more housework than men despite a narrowing gender gap in housework responsibility in recent decades (e.g., Shelton and John 1996). For example, time diary data from the United States revealed women did approximately six times more housework per week than men in the 1960s, dropping to just under two times as much in the 1990s (Bianchi et al. 2000) and early 2000s (Bianchi et al. 2012). These macro-level trends document historical variations in housework amid stability in how it is stratified by gender and are further supported by research exploring the division of household labour at distinct stages in the life course. Artis and Pavalko (2003) examined the housework contributions of women from five cohorts (ranging from young adulthood to midlife). They found that women in earlier cohorts assumed responsibility for more housework tasks than those in later cohorts, but all cohorts had similar rates of decline in housework 13 years later. Using reports of housework responsibility from 1618 couples at various life course stages (e.g., young couples without children, retirement), Rexroat and Shehan (1987) found women did more housework than men across all stages, with particularly large gaps when children were young. Further, the times during which men and women were most involved in housework differed: Women performed more household labour when they were rearing children, whereas men took on more household tasks when they were less involved in paid labour.

In addition to cross-cohort and cross-sectional studies on the division of household labour, researchers have utilized longitudinal data to explore how partners reorganize their housework patterns in response to occupational and family transitions. Grunow et al. (2012) found that although 44% of 1423 newlywed couples described their housework patterns as shared equally, nearly 85% reported having a traditional housework arrangement (i.e., women outperforming men) 14 years later (n = 518). Several studies identified parenthood as one of the key family transitions responsible for young adults’ shifts to an unequal division of household labour (Gjerdingen and Center 2005; Yavorsky et al. 2015). The gender gap in housework responsibility may decrease again, however, once children leave home and the partners have established stable careers or transitioned out of the paid labour market. For example, wives approaching midlife reduced their household labour over a 7-year period (Lam et al. 2012), and women did less housework and men doubled their housework hours across the transition to retirement in a German sample of 1302 mid- to later life couples (Leopold and Skopek 2015).

Taken together, these studies suggest that although men’s and women’s absolute housework hours may fluctuate over the life course, their relative performance seems to remain quite stable, given that women assume more responsibility for housework than men regardless of age or life stage. Research on differential patterns of partners’ division of household labour at distinct life positions is needed to see whether housework responsibility varies with changing developmental contexts. We draw on data from a Canadian cohort of individuals at three separate stages in their lives (the transition to adulthood, young adulthood, and midlife) exposed to similar sociocultural norms and historical contexts to examine housework responsibility within distinct developmental periods across time. Using more contemporary data (i.e., up to 2010), the present study will also aid in clarifying if the gender gap in housework has improved, worsened, or remained stagnant since the late 1990s.

Time-, Resource-, and Gender-Based Predictors

Personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors have been proposed to explain the division of household labour, which can be grouped into three main theoretical frameworks: time availability, relative resource, and gender perspectives (Shelton and John 1996). The time availability perspective purports couples make decisions about housework based on each partner’s time constraints (Coverman 1985; Presser 1994). Accordingly, individuals with limited free time from working longer hours in paid employment will spend less time on housework compared to those with fewer hours in paid labour or without employment. The relative resource perspective is grounded in an economic framework and proposes personal resources, such as one’s educational status, occupational prestige, or income, symbolize a form of power within an intimate union (Brines 1994; Ross 1987). Assuming that couples view household labour as undesirable, partners with more resources in intimate relationships (e.g., higher incomes) will exercise their resource power to “buy out” of doing housework.

Gender perspectives emphasize that housework has been historically constructed as “women’s work” (Coltrane 2000, p. 1209) and is, therefore, a prime arena for gender stratification. Gender theories are often divided into the gender ideology perspective and the more recent gender constructionist perspective. The gender ideology perspective proposes egalitarian men and traditional women will undertake more housework than traditional men and egalitarian women, respectively. From the gender constructionist perspective, partners reaffirm traditional gendered identities (women as homemakers and men as breadwinners) through repetitive performances of household labour, typically through women engaging in and men disengaging from housework (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard 2010; South and Spitze 1994). This unequal division of household labour is expected to be most pronounced in other-sex married couples, because the heterosexual institution of marriage contains the most ubiquitous, structured, and often traditional sociocultural norms about what constitutes “proper” gender behaviour for wives and husbands (Baxter et al. 2008). Likewise, parenthood is another social role that seems to prompt more traditional housework patterns from women and men (Yavorsky et al. 2015). Mothers are frequently cast as essential care providers and adept homemakers given their childbearing capabilities, whereas fathers are often viewed as “secondary and optional” (Barnes 2015, p. 353) in undertaking childcare and housework tasks. As such, we utilize gender, marital status, and raising children as proxies for the gender constructionist perspective.

Many studies have empirically tested whether time, resource, or gender-based factors are the strongest predictors of the division of household labour. Bianchi and colleauges' (2000) time diary data generally supported all three theories, with effects strongest for time availability (e.g., being unemployed) and gender (e.g., being a married woman) variables in predicting more housework responsibility. Although the authors did not explicitly assess relative resources, they found educated married women did less housework and educated married men did more housework compared to those with lower education levels. Analyzing survey data from a different sample of married partners, Bianchi et al. (2000) found longer work hours and earning a greater proportion of income in a partnership were tied to less housework time. More recent research also found women who earned a greater share of their family’s income, worked longer hours at their jobs, and espoused liberal gender-role attitudes assumed less household responsibilities (Mannino and Deutsch 2007) and that women did more housework if their husbands earned more money and worked longer hours than they did (Lam et al. 2012). Overall, these studies provide general support for time availability, relative resource, and gender perspectives on the division of household labour.

Yet, other research does not unequivocally support time, resource, or gender theories on housework responsibility. For example, some studies cast doubt on the relative resource perspective. Artis and Pavalko (2003) and Nitsche and Grunow (2016) found no association between partners’ relative income and housework changes or trajectories, and Bittman et al. (2003) found that women did less housework as their earnings increased to the same level as their partners’, but did more housework if they began to earn more than their partners. Results are also mixed for gender constructionist views: Although some studies found married women perform significantly more housework than cohabiting women and nonsignificant associations between marital status and men’s housework responsibility (Shelton and John 1993; South and Spitze 1994), other studies found no significant changes in men’s and women’s division of household labour after transitioning from cohabitation to marriage (e.g., Gupta 1999). Becoming a parent has also been linked to an increase in women’s housework responsibility and a decrease (Yavorsky et al. 2015) or lack of change (Baxter et al. 2008) in men’s housework responsibility.

Given the contested literature on what perspective(s) best explain the division of household labour, further exploration of these theoretical frameworks is necessary. A key limitation in the literature is that many studies exclude or control for theoretically relevant predictors of housework responsibility without systematically examining these variables, such as time availability (e.g., Bittman et al. 2003) or gender constructionist measures (e.g., Lam et al. 2012), precluding their ability to explicitly test the three competing theories. On the other hand, the studies that do compare the prominent theoretical perspectives on the division of household labour tend to examine the aggregate contribution of predictor variables without disentangling whether variables from each theory are more or less influential at different positions in the life course (e.g., Bianchi et al. 2000). No studies (to our knowledge) have addressed this latter question and, as such, this is the main contribution of the present work.

The time availability perspective, for example, might be a stronger predictor of housework responsibility in young adulthood when partners are trying to balance job searching or starting a new job while raising young children. Relative resource and gender constructionist perspectives may be more pertinent later in life once partners’ routines are stabilized after transitioning from school to work, cohabitation to marriage, and/or raising young children to launching children, whereas gender may play an important role in understanding housework responsibility regardless of life stage (e.g., Bianchi et al. 2012; Mannino and Deutsch 2007). We take a novel approach to refining knowledge on mid-range division of household labour theories by investigating them within a life course meta-theoretical framework and testing their relative predictive power at different life stages.

The Present Study

Guided by a life course theoretical approach, our study explores division of household labour patterns (e.g., who cooks meals, cleans the kitchen, does laundry) among men and women who were partnered during the transition to adulthood (age 25), in young adulthood (age 32), or in midlife (age 43). This study also examines associations between housework responsibility and variables representing time availability (i.e., number of weekly hours in paid employment), relative resource (i.e., having a higher income in one’s union), and gender constructionist (i.e., being married, raising children, gender) perspectives at three positions in the life course. We use regression analyses to test these associations in women and men and include education as a control variable, because those with higher educational levels tend to do less housework (Bianchi et al. 2000).

Based on the literature outlining gender differences in the division of household labour and mixed evidence for how time, resource, and gender variables predict housework responsibility, we propose two major hypotheses. First, we predict that although there will be slight variation in mean-level housework responsibility for men and women at each life stage, women will nevertheless perform more housework than men during the transition to adulthood, in young adulthood, and in midlife (Hypothesis 1). Second, we hypothesize that the relative strength of time, resource, and gender-related variables in predicting housework responsibility will differ depending on life stage (Hypothesis 2). In particular, we expect that working longer hours (time availability perspective) will be the strongest predictor of housework responsibility during the transition to adulthood and in young adulthood (Hypothesis 2a). At midlife, earning a higher relative income (relative resource perspective) and being married and raising children (gender constructionist perspective) will be stronger predictors of housework (Hypothesis 2b). Finally, gender (gender constructionist perspective) will moderate associations among the predictor variables and housework responsibility and, where it is not a moderator, it will be a significant predictor of housework responsibility (Hypothesis 2c).

Method

Procedure

The present study draws on data from three waves of the Edmonton Transitions Study (ETS) that began in 1985 to track young Canadians’ transitions from school to work and from adolescence to young adulthood. At baseline, 983 senior high school students (18-years-old) were recruited from a large Western Canadian city. Researchers inquired about participants’ educational and occupational experiences, family relations, sociopolitical ideologies, and personal goals and well-being. In 1986 (age 19), 1987 (age 20), 1989 (age 22), and 1992 (age 25), questionnaires were sent only to those individuals who participated in the prior wave. In 1999 (age 32) and 2010 (age 43), all baseline participants were re-contacted regardless of earlier participation. The present study draws on data from 1992, 1999, and 2010 because these are the waves containing relevant division of household labour items that are spaced far enough in time to represent distinct life stages (transition to adulthood, young adulthood, and midlife). The study received ethics approval for each wave of data collection, with the most recent ethics approval for the 2010 wave granted by the University of Alberta Arts, Science, and Law Research Ethics Board. Further study details are located in previous publications (e.g., Galambos et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2014; Krahn et al. 2015).

Sample

Given the focus on housework responsibility in couple relationships, the original samples from 1992 (n = 404), 1999 (n = 509), and 2010 (n = 405) were filtered to only include individuals partnered at that wave. We excluded single (228 in 1992, 145 in 1999, and 53 in 2010), separated/divorced (8 in 1992, 27 in 1999, and 42 in 2010), or widowed (1 in 2010) individuals, resulting in final subsamples of 168 in 1992, 337 in 1999, and 309 in 2010. It is important to note the participants in each age category are treated as three cross-sectional samples despite some potential overlap in participants at each wave because our data did not assess partnership changes or consistently measure certain variables at some study waves. Detailed demographic information for the sample at each wave is presented in Table 1.

Measures

Housework

Division of household labour in 1992, 1999, and 2010 was measured with the following question: “In your household, who usually does each of the following tasks?” Participants rated their housework responsibility in five core tasks (cooking meals, cleaning the kitchen, grocery shopping, house cleaning, and laundry), and responses were coded as 1 (spouse/partner), 2 (shared equally), 3 (respondent), or 4 (someone else). Responses that indicated someone else was responsible for a household task (such responses at each age ranged from .3% to 1.8% for cooking meals, 0% to 2.6% for cleaning the kitchen, 0% to .6% for grocery shopping, .6% to 10.1% for house cleaning, and 0% to 3.6% for laundry) were reassigned as missing, resulting in a response range from 1 to 3. Mean scores were computed, and higher scores correspond to respondents’ increased involvement in housework. Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for these items were .80 in 1992, .81 in 1999, and .85 in 2010.

Work Hours

The time availability perspective was assessed by participants’ time spent in paid labour. Participants reported the total hours each week they usually worked in 1992, and the sum of two items assessed participants’ work hours in 1999 and 2010: “On average, how many hours per week do you usually work in your (main) job?” and “On average, how many hours per week do you usually work in your other job(s)?” Higher scores corresponded to more hours spent in paid labour and, therefore, signify less time availability.

Higher Relative Income

The relative resource perspective was assessed by exploring participants’ proportional earnings in their households. Participants reported how much money they typically earned in a week (1992), month (1999), or year (2010) before deductions, as well as reported their total annual household incomes before taxes or deductions (all in Canadian dollars). Personal income in 1992 and 1999 was recoded into annual values for analysis. Relative income was coded as follows: 0 (participant earned less than 45% of household income), 1 (participant earned between 45% and 55% of household income), or 2 (participant earned more than 55% of household income). Higher scores correspond to having more relative resources in one’s relationship.

Being Married and Raising Children

The gender constructionist perspective was assessed by asking participants about their marital status and whether they were raising children. Given our necessary focus on individuals living with a partner, marital status was coded as 1 (cohabiting) or 2 (married). Participants reported whether they were raising children (own or partner’s) presently living in their households in 1992 and 1999, coded as 1 (no) or 2 (yes). In 2010, participants answered the question: “How many of your children currently live with you?” To parallel the 1992 and 1999 coding format, responses were dummy coded into respondents who had no children living with them (1 = no) or respondents who had any number of children living with them (2 = yes).

Education

Education was treated as a control variable in the present study. Participants were asked to report on the education degree(s) or diploma(s) they received in 1992 and 1999. In 2010, participants were asked to indicate their highest level of education. Responses across all waves were used to determine the highest level of education attained: 0 (less than high school), 1 (high school diploma), 2 (community college/technical diploma), 3 (university undergraduate degree), or 4 (university graduate degree).

Missing Data

Missing data in this sample ranged from 0% on respondent’s marital status at all waves to 19.2% on women’s reported relative income at age 43. We used the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach to handle missing data. FIML generates a maximum likelihood estimation of model parameters for missing values based on all available information in the variance/covariance matrix, and estimates tend to be similar to multiple imputation (but less biased than traditional deletion or mean substitution approaches; Johnson and Young 2011). FIML also assumes data are missing at random (MAR), where patterns of missingness are explained by other variables in the dataset rather than by scores on the key variables (Acock 2005). The MAR assumption for relative income (the variable with the most missing data) was confirmed through a series of logistic regressions with auxiliary variables (e.g., self-esteem, personal income, education) predicting the pattern of missingness.

Analytic Plan

After examining descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, we computed three independent samples t-tests to test mean level gender differences in the division of household labour at each position in the life course (i.e., women versus men during the transition to young adulthood; young adulthood; and midlife). Associations among housework responsibility and work hours, relative income, marital status, and raising children at each wave were then tested through multiple group regression analyses conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). The application of equality constraints and Chi-square difference testing in the multiple group models were used to examine how gender may moderate associations among housework responsibility and the variables from each theoretical perspective. Where gender does not moderate associations, it will be included as one of the predictors of housework responsibility.

Results

Testing Hypothesis 1

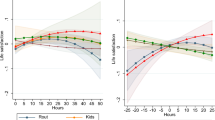

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables are presented in Table 1. Independent samples t-tests were computed to address Hypothesis 1, which predicted that women would perform more housework than men during the transition to adulthood, in young adulthood, and in midlife (despite minor mean-level variations in housework responsibility for men and women at each life stage). We found that women performed significantly more housework than men did during the transition to adulthood (women: n = 108, M = 2.40, SD = .39; men: n = 60, M = 1.65, SD = .35), t(166) = 12.34, p < .001, d = 1.92; in young adulthood (women: n = 180, M = 2.51, SD = .38; men: n = 157, M = 1.73, SD = .40), t(335) = 18.45, p < .001, d = 2.02; and in midlife (women: n = 167, M = 2.55, SD = .40; men: n = 141, M = 1.71, SD = .40), t(306) = 18.37, p < .001, d = 2.10—supporting Hypothesis 1. Notably, the largest gender difference in housework responsibility occurred for midlife men and women.

Bivariate Associations

Turning to the bivariate correlations (see Table 2), higher work hours and relative income were associated with less housework responsibility only for women during the transition to young adulthood (age 25), whereas raising children was associated with less housework only for men. For young adult (age 32) women, higher work hours and relative income were again linked to less housework responsibility. For young adult men, working longer hours was associated with less housework responsibility. Raising children was related to more housework for young adult women, but less housework for young adult men. Finally, working more hours and contributing a greater share to household income were associated with less housework for midlife (age 43) women, whereas raising children was associated with more housework. The only significant association between marital status and housework occurred at this midlife stage: being married was linked to more housework responsibility for midlife women. Higher work hours and relative income were associated with less housework for midlife men. Taken together, these bivariate associations provide preliminary evidence that work hours, relative income, marital status, and raising children may differentially contribute to the division of household labour depending on one’s position in the life course and gender.

Testing Hypothesis 2

We conducted multiple group regression analyses in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) to test the remaining research hypotheses. Hypothesis 2 (the relative strength of time, resource, and gender-related variables in predicting housework responsibility will differ depending on life stage) and each follow-up hypothesis were tested by first computing the conceptual model for men and women at each life stage, with work hours, relative income, marital status, and raising children predicting housework. To determine whether gender moderated associations among the exogenous variables and housework responsibility, we constrained associations to equality one-by-one and computed a Chi-square difference test for each comparison. If an association differed for men and women (i.e., constraint reduced model fit as evidenced by a statistically significant difference in the Chi-square difference test), then the two-group model was retained. If gender did not moderate associations, then models were rerun with gender added as a predictor (given robust associations between housework responsibility and gender; Bianchi et al. 2012). After testing moderation by gender, the control variable (education) was added by regressing it on housework responsibility. Last, we constrained associations to equality one at a time to test the relative strength of each variable as a predictor of housework and computed Chi-square difference tests. Throughout the analysis, we examined global fit indices (global fit testing) and residuals (local fit testing) to check for areas of model misfit. The final models had good fit to the data, as evidenced by their strong global fit statistics and local inspection of model fit (e.g., residuals) showing no isolated areas of model misfit.

The results from the final models are presented in Table 3. The magnitude of the regression coefficients for work hours, relative income, marital status, raising children, and gender in predicting housework responsibility differed in substantive ways across the three life stages, supporting Hypothesis 2. Thus, the degree to which time availability, relative resource, and gender constructionist perspectives best explain housework responsibility seems to depend on stage in the life course—a core finding we expanded in the following.

Hypothesis 2a proposed that work hours (time availability perspective) would best explain housework responsibility during the transition to adulthood (age 25) and in young adulthood (age 32). In line with this hypothesis, we found working longer hours predicted less housework responsibility for men and women at age 25 and 32. Yet we also found the inclusion of gender in the age 25 model reduced work hours to nonsignificance and strengthened the predictive power of relative income. As such, Hypothesis 2a was partially supported.

Hypothesis 2b proposed that earning a higher relative income (relative resource perspective) and being married and raising children (gender constructionist perspective) would best explain housework responsibility in midlife (age 43). We found more work hours and earning a larger share of household income predicted less housework responsibility and, importantly, relative income was the stronger predictor, which supported our hypothesis. Relative income was, however, also significant in the age 25 models. To further contest our hypothesis, being married was not a significant predictor of housework at any life stage, and raising children was linked to less housework responsibility for young adult men only (i.e., the association was nonsignificant for young adult women). These results provided partial support for Hypothesis 2b.

Finally, Hypothesis 2c proposed that gender (gender constructionist perspective) would moderate associations among the predictor variables and housework responsibility at all life stages or significantly predict housework responsibility where it is not a moderator. We found gender only moderated associations in the age 32 model. Because gender did not moderate any associations between the variables in the age 25 and 43 models, an overall model was computed without the multiple group component to enable comparability to the age 32 model. When gender was included as a covariate at age 25 and 43, being male was by far the strongest predictor of less housework responsibility. Thus, Hypothesis 2c was supported.

Discussion

Drawing on a life course theoretical framework, we examined men’s and women’s division of household labour patterns during the transition to adulthood (age 25), in young adulthood (age 32), and in midlife (age 43) and investigated the contributions of work hours, relative income, marital status, and raising children on housework responsibility at these three life stages. Our first key finding was that prominent differences emerged between men’s and women’s average housework scores at each life stage. Aligning with several empirical and review studies on gender differences in the division of household labour (e.g., Bianchi et al. 2000; Rexroat and Shehan 1987; Shelton and John 1996) and in support of Hypothesis 1, women assumed more housework responsibility than men did at all ages. Although this overall gender difference may not be surprising, the most intriguing aspect of this finding was that the largest gender gap in housework occurred among midlife participants at the most recent wave of assessment (i.e., 2010). Both sociohistorical and developmental interpretations may help shed light on this finding. On the one hand, we could be in the midst of a newly intensified “stalled [gender] revolution” (Hochschild 1989, p. 11) in unpaid labour compared to prior decades, where men’s housework responsibility is not rising sufficiently alongside women’s growing labour force participation. Indeed, whereas the housework gender gap generally declined between the 1960s and 1990s, men’s housework hours peaked in the late 1990s and have dropped since this time (Bianchi et al. 2012).

On the other hand, these findings may be due to unique differences in how midlife individuals organize housework and perceive gender relations compared to those in earlier life stages. Partners tend to assume more traditional housework patterns (i.e., women doing more) as their relationships progress (Grunow et al. 2012), and midlife adults espouse more traditional gender role ideologies than younger adults do (Sweeting et al. 2014). Of course, these sociohistorical and developmental interpretations could be considered simultaneously: perhaps contemporary midlife partners experience the largest housework gender gap from a mutual reinforcement between their more traditional gender attitudes and behaviours and the sociocultural shift toward lessening equality in unpaid work proposed by recent research. Exploring how men’s and women’s division of household labour is influenced by the interrelations among historical time, changing social norms, and life course position presents an exciting area for future research.

Moving onto the primary contribution of our study and in alignment with Hypothesis 2, we found that the significance of time, resource, and gender variables predicting housework responsibility showed some differences depending on life stage. In general, having a higher relative income predicted less housework during the transition to adulthood, working longer hours and raising children (for men only) predicted less housework in young adulthood, and both work hours and relative income predicted less housework in midlife (partially supporting Hypotheses 2a and 2b). Not only did gender moderate results at age 32, but once gender was included in the age 25 and 43 models, the effect for work hours reduced to nonsignificance at age 25 and declined in magnitude at age 43, and being male was the strongest predictor of less housework during the transition to adulthood and in midlife (supporting Hypothesis 2c).

These results can be understood from the distinct developmental contexts that accompany these positions in the life course alongside the recognized gendered nature of housework. The transition to adulthood (age 25 in our sample) is often characterized by instability, frequent role changes, and concurrent stressors from experiencing several major life transitions within a relatively short time span, such as securing employment, attaining financial independence, and establishing one’s reputation as a diligent employee (Schulenberg et al. 2004). At first glance, it seems “time is of the essence” during this unstable and demanding life stage, and performing less housework to counteract higher paid work hours could be one way individuals in their early 20s try to conserve the already limited time they have. The fact that the inclusion of gender overrode the medium-size impact of work hours on housework responsibility in the transition to adulthood, however, highlights the power of the gendered nature of housework. The link between more work hours and less housework responsibility is more a function of the fact that men do less housework and they work more hours. In other words, it is not more work hours that keep 25-year-old men from doing more housework. Perhaps men perform less housework to reaffirm their masculinity, independence, and sense of control in a developmental period characterized by uncertainty and fluidity. Importantly, earning a greater share of income remained a significant predictor of housework once gender was accounted for, demonstrating the utility of the relative resource perspective at this life stage.

Although the midlife period entails its own unique challenges (e.g., health concerns, generativity), employment experiences tend to stabilize as individuals solidify their work identities, maximize their incomes, and attain occupational prestige (Lachman 2004). If midlife individuals are more likely to put in longer hours in paid labour to better reach their earning potentials and accumulate more resources overall given their older age, then their limited time and greater share of income may be used as bargaining chips to lessen their involvement in unpaid labour. Despite the importance of work hours and relative income in midlife, however, being a man is still the strongest predictor of less housework responsibility at this life stage. Personal and social constructions of housework as a feminine task may ultimately drive midlife men’s behaviour in the home more strongly compared to time or money, especially because traditional gender role attitudes are more common among men in general and older men in particular (Sweeting et al., 2010). Taken together, time availability and relative resource perspectives both play roles in understanding the division of household labour for men and women in young adulthood and in midlife (to varying degrees).

Aspects of the gender constructionist perspective were relevant at all three life stages. Gender was strongly linked to housework responsibility at age 25 and 43, as predicted, and it moderated the potential influence of raising children on housework. Although marital status was not significantly associated with housework responsibility at any age, the age 32 gender moderation analysis revealed that raising children was associated with less housework for young adult men (and a nonsignificant but positive association for young adult women). Further, more work hours was a stronger predictor of lower housework responsibility compared to marital status or raising children for young adult women, whereas work hours and raising children were equally strong predictors of young adult men’s lower housework responsibility. Thus, time availability and gender-based divisions of labour are relevant for both young adult women and men.

Why was marriage versus cohabitation unrelated to housework? Relationship status may be less important for the division of household labour than the mere presence of an other-sex partner to perform one’s gender-related tasks (Baxter et al. 2008; Gupta 1999), especially because cohabitation has become more common, acceptable, and “marriage-like” (Bianchi 2011, p. 22). Likewise, if marriage is in the process of becoming deinstitutionalized (i.e., weakening of traditional norms that structure husband and wife roles) as Cherlin (2004) argued, husbands and wives may not experience strong social pressures to align their behaviours with traditional gender displays based on marital status.

Instead, it may be one’s parental status—a status typically acquired in young adulthood— that serves as a primary motivator of traditional housework patterns due to complex intersections of women’s biological role in childbearing with familial, sociocultural, economic, and political factors influencing parents’ behaviours in recent decades. Young parents not only renegotiate their own relationship and domestic environment when young children become part of the home, but also are exposed to cultural ideologies that laud intensive mothering and the “natural skills” of women as nurturers and homemakers, workplace policies that limit or do not offer paternity leave, and childcare options that may be unaffordable or incompatible with paid work schedules (Barnes 2015; Hays 1996). These contextual forces may pressure young adult women to perform childcare and housework tasks seamlessly without these tasks impacting each other or perceive these tasks as reasonable extensions of each other while simultaneously discouraging young adult men from being involved in housework. Being a husband and wife versus a male partner and female partner may therefore entail similar expectations of normative gendered behaviour toward tasks like housework, but assuming the role of a father or mother may be more heavily structured by contextual forces that encourage men’s and women’s differential housework responsibility in young adulthood. As such, it may be beneficial for researchers to incorporate parental status into conceptualizations of the gender constructionist perspective, especially if they are studying the division of household labour in young adulthood.

Corroborating Bengston and Allen’s (1993, p. 493) assertion that the life course paradigm is “well-suited to the process of theory building and testing,” our findings also highlight the importance of synthesizing a meta-theoretical paradigm with mid-range perspectives on housework responsibility to unearth the nuances in how partners organize housework across the life course. Integrating a life course perspective with time-, resource-, and gender-based theories on the division of household labour enabled us to discern how certain predictors matter more or less (or not at all) for housework responsibility at different life stages, which further refines the utility and distinct contribution of each individual housework theory. Indeed, although there may be similarity in how housework is divided at different times in their lives, there is also notable variability in why partners within distinct life stages organize housework in a certain pattern.

Practice Implications

The results of our study can help promote gender equality on a societal level while also building partners’ awareness of the many factors that shape domestic life at different stages in the life course. Our findings demonstrate the persistent gendered nature of how housework is divided, which can be used by policymakers and employers to develop or alter laws, policies, and work environments in ways that promote men’s involvement in unpaid labour. Our results also suggest it would be important for couples therapists and educators to encourage partners to reflect on their stage in the life course and the associated stressors that may shape their household decision making. Practitioners could employ different approaches in working with couples who disagree about who should do what in the household—or disagree more broadly about relationship roles, power, and equity—depending on their age and life stage, directing conversation toward or away from employment schedules, earnings, and/or raising children.

More generally, couples of all ages could be encouraged to explore their own gendered assumptions surrounding housework, the foundations of these beliefs (e.g., family of origin, media, workplace norms), and whether these beliefs translate into housework strategies that work best for both partners’ preferences, paid work arrangements, and family requirements.

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting our findings. First, because we had too few participants in each wave and our data did not assess whether participants remained partnered to the same individuals at each time point, we were unable to analyze the data longitudinally. Likewise, participants were coupled with partners outside the study (rather than each other), which precluded our ability to perform dyadic analyses. Following the lead of more recent longitudinal housework studies (e.g., Baxter et al. 2008; Lam et al. 2012), future research could test the relative contributions of time, resource, and gender predictors of housework within partners as they move through the life course together. Second, we tested each conceptual approach on the division of household labour with one item. The Edmonton Transitions Study measured a diverse range of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and sociocultural variables, which inevitably led to condensed scales and some potentially relevant constructs being unassessed at all waves. Operationalizing each theoretical perspective on housework with more comprehensive, multi-item measures is an important direction for future research. Third, it would be worthwhile to compare whether work hours, relative income, and marital status or raising children are linked to housework responsibility in similar or different ways for same-sex and different-sex couples, because past research has shown same-sex partners generally divide housework tasks in more equal ways compared to those in other union types (Goldberg 2013).

Conclusion

Our study explored men’s and women’s division of household labour at different ages (25, 32, and 43), as well as time-, resource-, and gender-based predictors of housework at these three distinct positions in the life course. Patterns of housework responsibility between men and women tended to be quite consistent at each life stage despite minor fluctuations in mean level housework scores, with women consistently performing more housework than men do. Moreover, variables from time availability, relative resource, and gender constructionist perspectives differentially predicted housework responsibility based on stage in the life course. In particular, the time availability perspective was supported in young adulthood and in midlife, the relative resource perspective was supported during the transition to adulthood and in midlife, and different components of the gender constructionist perspective were supported at all three life stages (i.e., gender moderated the influence of parenthood on housework in young adulthood and was a strong predictor of housework responsibility in the transition to adulthood and in midlife). Overall, time, money, and gender variables seem to be important for explaining the division of household labour, albeit to varying intensities depending on stage in the life course. Nevertheless, gender constructionism ultimately mops up the competition of housework theories in early and later life, with a notable presence in young adulthood as well.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1012–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x.

Artis, J. E., & Pavalko, E. K. (2003). Explaining the decline in women’s household labour: Individual change and cohort differences. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 746–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00746.x.

Barnes, M. W. (2015). Gender differentiation in paid and unpaid work during the transition to parenthood. Sociology Compass, 9, 348–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12263.

Baxter, J., Hewitt, B., & Haynes, M. (2008). Life course transitions and housework: Marriage, parenthood, and time on housework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00479.x.

Bengston, V. L., & Allen, K. R. (1993). The life course perspective applied to families over time. In P. Boss, W. Doherty, R. LaRossa, W. Schumm, & S. Steinmetz (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 469–499). New York, NY: Plenum.

Bianchi, S. M. (2011). Family change and time allocation in American families. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638, 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716211413731.

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labour. Social Forces, 79, 191–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/79.1.191.

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos120.

Bittman, M., England, P., Sayer, L., Folbre, N., & Matheson, G. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109, 186–214. https://doi.org/10.1086/378341.

Brines, J. (1994). Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labour at home. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 652–688. https://doi.org/10.1086/230577.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labour: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1208–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x.

Coverman, S. (1985). Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labour. The Sociological Quarterly, 26, 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1985.tb00217.x.

Dannefer, D. (1984). Adult development and social theory: A paradigmatic reappraisal. American Sociological Review, 49, 100–116. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095560.

Elder Jr., G. H. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2786971.

Elder Jr., G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Krahn, H. J. (2006). Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology, 42, 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350.

Gjerdingen, D. K., & Center, B. A. (2005). First-time parents’ postpartum changes in employment, childcare, and housework responsibilities. Social Science Research, 34, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.005.

Goldberg, A. E. (2013). “Doing” and “undoing” gender: The meaning and division of housework in same-sex couples. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5, 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12009.

Grunow, D., Schulz, F., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2012). What determines change in the division of housework over the course of a marriage? International Sociology, 27, 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580911423056.

Gupta, S. (1999). The effects of transitions in marital status on men’s performance of housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 700–711. https://doi.org/10.2307/353571.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Viking.

Johnson, D. R., & Young, R. (2011). Toward best practices in analyzing datasets with missing data: Comparisons and recommendations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 926–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00861.x.

Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L., & Krahn, H. J. (2014). Depression and anger across 25 years: Changing vulnerabilities in the VSA model. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036087.

Krahn, H. J., Howard, A. L., & Galambos, N. L. (2015). Exploring or floundering? The meaning of employment and educational fluctuations in emerging adulthood. Youth Society, 47, 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12459061.

Lachance-Grzela, M., & Bouchard, G. (2010). Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles, 63, 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9797-z.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521.

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2012). The division of household labour: Longitudinal change and within-couple variation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 944–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01007.x.

Leopold, T., & Skopek, J. (2015). Convergence or continuity? The gender gap in household labour after retirement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12199.

Mannino, C. A., & Deutsch, F. M. (2007). Changing the division of household labour: A negotiated process between partners. Sex Roles, 56, 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9181-1.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nitsche, N., & Grunow, D. (2016). Housework over the course of relationships: Gender ideology, resources, and the division of housework from a growth curve perspective. Advances in Life Course Research, 29, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2016.02.001.

Presser, H. B. (1994). Employment schedules among dual-earner spouses and the division of household labour by gender. American Sociological Review, 59, 348–364. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095938.

Rexroat, C., & Shehan, C. (1987). The family life cycle and spouses’ time in housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 737–750. https://doi.org/10.2307/351968.

Ross, C. E. (1987). The division of labour at home. Social Forces, 65, 816–833. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2578530.

Schulenberg, J. E., Bryant, A. L., & O’Malley, P. M. (2004). Taking hold of some kind life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1119–1140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040167.

Shelton, B. A., & John, D. (1993). Does marital status make a difference? Housework among married and cohabiting men and women. Journal of Family Issues, 14, 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251393014003004.

Shelton, B. A., & John, D. (1996). The division of household labour. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.299.

South, S. J., & Spitze, G. (1994). Housework in marital and nonmarital household. American Sociological Review, 59, 327–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095937.

Sweeting, H., Bhaskar, A., Benzeval, M., Popham, F., & Hunt, K. (2014). Changing gender roles and attitudes and their implications for well-being around the new millennium. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 791–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0730-y.

Yavorsky, J. E., Kamp Dush, C. M., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2015). The production of inequality: The gender division of labour across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12189.

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Alberta Advanced Education, and the University of Alberta to Harvey Krahn and colleagues. Data were collected by the Population Research Laboratory, University of Alberta.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

We have complied with all ethical standards of human subjects research in our manuscript. This study received ethics approval prior to each wave of data collection; the most recent ethics approval for the 2010 survey was granted by the University of Alberta Arts, Science and Law Research Ethics Board (application title: Transitions to Adulthood: 25 Year Follow-up of the Class of 1985; protocol number: Pro00015384).

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflict of interest to report.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horne, R.M., Johnson, M.D., Galambos, N.L. et al. Time, Money, or Gender? Predictors of the Division of Household Labour Across Life Stages. Sex Roles 78, 731–743 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0832-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0832-1