Abstract

This short-term longitudinal study expands on previous theoretical approaches, as we examined how women’s assertiveness and the strategies they use to elicit more household labor from husbands help to explain the division of labor and how it changes. Participants included 81 married women with 3- and 4-year-old children who completed two telephone interviews, approximately 2 months apart. Results based on quantitative and qualitative analyses show that (a) relative resource, structural, and gender ideology variables predicted the division of housework, but not childcare; (b) assertive women were closer to their ideal division of childcare than nonassertive women; (c) women who made a larger proportion of family income were less assertive about household labor than other women, but when they were assertive, they had a more equal division of childcare; (d) women who earned the majority of their household’s income showed the least change; and (e) the nature of women’s attempts to elicit change may be critical to their success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite the amelioration in women’s political and economic rights and their increased presence in the paid workforce since the 1960s, household labor and childcare remain divided along traditionally gendered lines (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Thompson & Walker, 1989). Past researchers have examined what factors influence and maintain this gendered division of labor, and have noted the importance of everyday interactions between husbands and wives in creating this inequitable division (e.g., Coltrane, 1990, 2000; Deutsch, 1999; England & Farkas, 1986; Ferree, 1990, 1991; Hood, 1983; Risman & Johnson-Sumerford, 1998; Szinovacz, 1987; Thompson & Walker, 1989). Researchers have also begun to explore the relationships between conflict, negotiation, and the division of labor (Coltrane, 1989; Deutsch, 1999; Hood, 1983; Risman & Johnson-Sumerford, 1998). However, further examination is now needed of how specific strategies in couples’ conflicts affect their division of labor and the likelihood of their changing it. In the current study, we explored these connections further.

Evidence for the Persistence of a Gendered Division of Labor

Numerous studies document the persistence of a gendered division of domestic labor (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Dempsey, 1997; England & Farkas, 1986; Ferree, 1990, 1991; Kluwer, Heesink, & Van de Vliert, 1997; Presser, 1994; Thompson & Walker, 1989). In most couples, wives spend much more time on household tasks than their husbands do (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Dempsey, 1997, 2002; Johnson & Huston, 1998; Kluwer, Heesink, & Van de Vliert, 1996, 2000; Presser, 1994; Thompson & Walker, 1989). Even employed wives assume the larger portion of household chores (e.g., Dempsey, 2002) during what Hochschild (1989) dubbed their second shift. Not only do women retain responsibility for completing the childcare and household duties (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Dempsey, 2002; Thompson & Walker, 1989), but they also manage, plan, organize, and supervise them. Women usually perform the most necessary and time-consuming tasks on a daily basis. Men may help with these typical women’s tasks but rarely assume equal daily responsibility. Usually, men take on the responsibility only for typical men’s outdoor tasks that need to be completed less frequently, such as mowing the lawn (Coltrane, 2000; Ferree, 1990; Thompson & Walker, 1989).

Prominent Theories

A number of theoretical perspectives have been proposed to account for the gendered division of labor. The most prominent among them are the resources, the structural factors, the gender ideology, and the gender construction approaches (e.g., Berk, 1985; Coltrane, 2000; England & Farkas, 1986; Kluwer et al., 2000; Presser, 1994). Classic resource theories propose that relative resources are a key determinant of how household labor is divided (e.g., Ferree, 1991). This approach suggests that a spouse’s external resources, such as income, education, and occupational status, confer power. Thus, the spouse with the greater resources also has the greater decision-making power to put his/her wishes into practice (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Johnson & Huston, 1998; Presser, 1994), and that power is used to reduce his/her own share of domestic labor. Thus, the greater a spouse’s share of relative resources, the smaller his/her share of housework and childcare (e.g., Coverman, 1985; Deutsch, Lussier, & Servis, 1993; Presser, 1994).

The structural factors approach examines how personal and family characteristics, such as the amount of time a wife works outside the home as well as the number and ages of children present in the home, influence the division of household labor. The demand-response model, for example, asserts that the more structural demands placed on a spouse to participate in household labor and the more time s/he has available to do so, the greater the amount of household labor s/he performs (e.g., Coverman, 1985; Deutsch et al., 1993; Presser, 1994).

A third perspective, the gender ideology model, proposes that attitudes toward gender roles are responsible for the division of household labor (e.g., Coverman, 1985; Deutsch et al., 1993; Kluwer et al., 1997, 2000). Men and women who have more egalitarian ideologies tend also to have more equal divisions of labor (e.g., Shelton & John, 1996). The more traditional husbands’ and wives’ gender ideologies, the less husbands will participate in housework (e.g., Coverman, 1985).

The resources, structural factors, and gender ideology perspectives typically ignore that the division of labor is actively negotiated between spouses on a continual and daily basis (Kluwer et al., 2000; Pittman, Solheim, & Blanchard, 1996). Instead, these theories explain the gendered division of labor as though it were static and changed little over time (Pittman et al., 1996). In the last two decades, gender construction theories have emerged to offer a more interactional outlook. Gender construction theories propose that men and women engage in different household tasks to demonstrate and reaffirm their gendered selves. The ongoing and daily interactions concerning the division of household labor comprise a context in which gendered behavior as masculine or feminine is created, maintained, and renegotiated (Berk, 1985; Coltrane, 1989, 2000; Fenstermaker, West, & Zimmerman, 1991; Ferree, 1990; Kluwer et al., 2000; Osmond & Thorne, 1993; Risman, 2004; Thompson & Walker, 1989).

In line with the gender construction theory, several qualitative studies have been conducted to examine the division of household labor through couples’ negotiations. Hood (1983) examined couples’ negotiations over an 8-year period to explore how and why families change after wives take on paid employment. Coltrane (1989, 1990) explored how dual-earner couples discussed sharing childcare and housework and how they negotiated these tasks. In his 1989 study, Coltrane found evidence for change in the meaning of gender; when household labor was shared equally, fathers developed maternal thinking. Likewise, Deutsch (1999) explored couples’ retrospective accounts of the interactions and discussions that enabled them to share childcare equally. Risman and Johnson-Sumerford (1998) also interviewed “post-gender” couples to determine how they had developed the arrangement of sharing household tasks equally. They concluded that the interactions of these unique couples were characterized by egalitarian friendships and guided by fairness and sharing principles.

The gender construction approach has proved helpful in addressing several limitations of previous perspectives (Ferree, 1990): specifically, why inconsistencies exist between earlier theories and empirical findings, and why a gendered division of labor persists. Even when women make as much money as men, work as many hours, and believe in liberal gender ideology, they still do more domestic labor than men do. In fact, more income can sometimes lead women to do more housework. Although a woman’s share of housework decreases when her share of household income increases, as would be predicted by resource theory, once her income exceeds her husband’s, some studies have shown that her share of household labor rises again (Bittman, England, Folbre, Sayer, & Matheson, 2003; Brines, 1994; Ferree, 1990; Tichenor, 1999). Gender construction theorists explain this curvilinear relationship as couples’ attempts to reduce the threat to the husbands’ masculinity and to reaffirm the wives’ femininity in the face of their “masculine” income-generating behavior (Bittman et al., 2003; Brines, 1994; Ferree, 1990; Thompson & Walker, 1989; Tichenor, 1999). These women may judge their contributions and success as a wife and mother by how much work they do inside the home (Ferree, 1990; Thompson & Walker, 1989; Tichenor, 1999).

Moreover, by eschewing power, wives can avoid marital conflict. Brines and Joyner (1999) argued that when a wife’s income becomes closer to her husband’s, there is a greater chance of disruption than of potential gain. The more a wife earns relative to her husband, the greater the couple’s risk of divorce (Brines & Joyner, 1999). Thus, when high-earning women do not use their greater resources to claim more power, they may be returning control to their husbands to avoid marital discord as well as to live up to normative standards of femininity.

The effect of women’s resources, and their influence in encouraging or discouraging a more equitable division of household labor, is also dependent on how provider roles are defined in a marriage and on the meanings and value given to women’s paid employment (Hood, 1983; Potuchek, 1992; Pyke, 1994). Income may only increase wives’ power under some circumstances (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1991). For instance, Perry-Jenkins, Seery, and Crouter (1992) found that husbands of women who identified themselves as coproviders, viewing breadwinning as a responsibility that husbands and wives should share equally, spent more time completing household tasks than did husbands of homemakers and women who viewed their income as helpful but not essential.

The gender ideology model also fails to account for why women continue to do more domestic labor when both they and their husbands have liberal gender ideologies. Such women may judge their actions and worth as mothers by an idealized standard of motherhood, even when they reject that standard in principle (Deutsch, 1999). Based on the gender construction approach, living up to this ideal and accepting a division of labor where they retain major responsibility for the housework and childcare may be a way that women “do gender.” Women may feel discomfort when they move away from their motherly roles (Major, 1993).

Differences between housework and childcare

The resources, structural factors, and gender ideology perspectives attempt to explain domestic labor as a whole; they fail to distinguish between housework and childcare. However, many researchers have examined housework and childcare as distinct areas, and found that their nature and predictors differ (e.g., Bianchi & Raley, 2005; Coltrane & Adams, 2001; Deutsch et al., 1993; Hood, 1983; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992). For example, some empirical work indicates that housework is more likely than childcare to be affected by wives’ relative income (Deutsch et al., 1993; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992). Other studies suggest that childcare may involve more of a joint agreement between spouses and that fathers spend more time in childcare than in housework tasks (Bianchi & Raley, 2005; Hood, 1983). Thus, to understand changes in the division of domestic labor, it is important to evaluate housework and childcare as distinct activities.

Negotiation, Conflict, and the Division of Labor

Negotiation

Couples who are married or living together make decisions everyday about who will do what (Kirchler, 1993). Those decisions determine not only their day-to-day routine but also their future behaviors and the balance of power between them (Coltrane, 2000; Zvonkovic, Schmiege, & Hall, 1994). Although Hood (1983), Coltrane (1989, 1990), Deutsch (1999), and Risman and Johnson-Sumerford (1998) have explored connections between conflict, negotiations, and the division of labor, and their qualitative studies suggest that links do exist, more detailed insight is needed to understand fully how the three are related and what this means for change. Hood (1983) acknowledged the necessity of further exploring, in specific detail, the relationships among communication, conflict and the division of household labor. Likewise, Szinovacz (1987) echoed a similar sentiment; he stated that it is important to study family interactions, such as in negotiation and conflict situations, to understand the processes of family power (Szinovacz, 1987).

A few researchers have explored the relationship between communication, conflict and the division of labor in more detail. For example, Pittman et al. (1996) examined the division of household labor with a microprocess approach and conceptualized housework as an activity that couples decide to engage in on a daily basis. They found that stress, a constantly changing variable, helped to predict a more dynamic allocation of housework time. Non-home-based stress, such as a job stress, decreased time spent on housework by the stressed party on a particular day, regardless of gender. In addition, non-home-based stress from one day carried over to the next day and influenced that day’s division of domestic labor as well. Thus, examinations of stress illustrate how the division of labor is a product of ever-changing and active decision-making processes that are influenced by the surrounding social environment (Pittman et al., 1996).

The role of conflict

Although many women do not think that the inequitable division of labor in their homes is unfair (Baxter, 2000; Dempsey, 1999; Sanchez, 1994), many do. In fact, the division of household labor, including housework and childcare, is one of the greatest areas of conflict (e.g., Kluwer et al., 1996, 2000) and dissatisfaction for married couples (Kluwer, 1998). Wives often wish that their husbands would participate in household tasks and childcare more than they actually do (e.g., Johnson & Huston, 1998; Kluwer et al., 2000), and many prefer their husbands to share the daily responsibility for these tasks instead of simply helping with them (Dempsey, 2000). Wives are more likely than their husbands to be angry over the division of household labor, to express their unhappiness with the distribution of tasks, to raise these issues with their husbands, and to instigate change (Deutsch, 1999; Kluwer et al., 1996, 1997; Risman & Johnson-Sumerford, 1998).

Conflict is not necessarily negative. Perhaps women’s lead role in conflicts over household labor indicates their increasing sense of entitlement to a more equitable division of housework and childcare (Ferree, 1990; Kluwer et al., 2000). Marital interactions and conflicts may provide a means for women to move away from more traditional gender roles (Kluwer et al., 1996, 1997). However, change may depend on the way in which conflicts are conducted. Kluwer et al. (2000) studied spouses’ attempts, through hypothetical conflict interactions concerning paid work, childcare and housework, to maintain or change a gendered division of labor. In many instances a wife-demand, husband-withdraw scenario was activated that further fueled the argument and hampered change. In this type of conflict pattern wives generally attempt to begin a discussion with their husbands by pressuring, demanding, blaming, or criticizing. Their husbands, in response, distance themselves by withdrawing, defending, or becoming silent (Kluwer et al., 2000).

Assertiveness (i.e., the willingness to state one’s desires in a clear, direct, straightforward way) may be a key component of change. In a study of plans for an egalitarian marriage among college seniors, Deutsch, Kokot, and Binder (2006) found that an assertive conflict resolution style was associated with women’s plans to have a marriage in which both spouses scaled back on paid work to care for children. Thus, women with assertive conflict resolution styles may expect to gain a more egalitarian division of labor by negotiating with their husbands and clearly stating their desires (Deutsch et al., 2006).

Although assertiveness may be important, as yet, we do not know exactly how it works. Assertiveness and income may be related in different ways. It is possible that assertiveness mediates the effect of women’s income on their share of domestic labor. Bringing income into the family may entitle women to argue assertively for a reduction in their relative share of housework and childcare, except when their incomes exceed their husbands’. Then, the pressure to behave in more gendered ways could reduce their assertiveness about household labor which would explain the increase in wives’ share of domestic labor when they outearn their husbands (Bittman et al., 2003; Brines, 1994; Ferree, 1990; Tichenor, 1999). Alternatively, income may inhibit assertiveness by acting as a source of power on its own. Accordingly, to the extent that women bring in income, they have less need to be explicitly assertive to get what they want. Moreover, assertiveness coupled with too much income may threaten husbands and foment serious conflict. Finally, as we predicted, based on the Deutsch et al. (2006) finding, the influence of assertiveness may be completely independent of income. Regardless of their income, more assertive women may simply get their husbands to do more household labor.

Change may also be facilitated by a woman’s plans to achieve a more equal division of household labor. According to the theory of planned behavior, a person’s intentions are a critical predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 2001). In fact, several studies have demonstrated that forming intentions (i.e. plans) is effective in influencing behavior, such as eating healthier, exercising, attending cancer screenings, attempting to quit smoking, and graduating high school (Conner, Norman, & Bell, 2002; Davis, Ajzen, Saunders, & Williams, 2002; Norman, Conner, & Bell, 1999; Rise, Thompson, & Verplanken, 2003; Sheeran & Orbell, 2000; Verplanken & Faes, 1999). We hypothesized that women who plan to change the division of labor will be more likely than other women to attempt change and that those who attempt change will show the greatest change.

In the current exploratory study, we sought to extend previous research and to examine how specific conflict processes regarding housework and childcare affect women’s success in creating a more equal division of labor. If the division of household labor remains gendered, to what extent do women want to change it? If they do want change, how do they attempt to enact it and in what ways do they discuss the issue? Are they assertive, demanding change in a clear and direct manner? In essence, by paying attention to conflict-related variables, such as assertiveness, can we increase our understanding of how household labor is divided and how it might be changed to reduce inequality? If creating a division of labor is an ongoing process, then it should be possible to examine both fleeting changes in response to outside events, as Pittman et al. (1996) did, and changes toward a more equal division of labor over a relatively short period of time. To do so, we used a short-term longitudinal design and interviewed women about the division of labor in their families twice over a period of approximately 2 months. We expected that women’s desire to change, plans to advocate for a more equal division of labor, attempts to do so, and their assertiveness would predict greater change over the 2 months above and beyond changes predicted by their percent income and/or work hours.

Method

Participants

We used town hall birth records of a New England town for the years 1999 and 2000 to identify couples who had either 3- or 4-year-old children. Given that we sought to examine the division of labor between husbands and wives, only couples who were married and living together were eligible for the present study.Footnote 1 In addition, we only interviewed wives because wives tend to be more discontented with the division of household labor than their husbands and, thus, more likely to desire a change (Deutsch, 1999; Kluwer et al., 1996, 1997; Risman & Johnson-Sumerford, 1998). All participants were recruited through an initial letter of intent and then a follow-up telephone call. Recruitment for the second interview was based upon permission given at the end of the first interview. Upon completion of both the first and second interviews, participants were entered into two separate $50 raffles. Of the 127 participants initially contacted for the first interview, five letters were returned with incorrect addresses, 17 telephone numbers had either been disconnected or were no longer in service, three participants were not eligible because they lived in a single-parent household, seven declined participation, and 14 were not able to be reached. Of the 102 eligible women, 81 participated yielding a response rate of 79.4%. Of the 81 participants from the first interview, three declined to participate in the second interview and three could not be reached, thus yielding a response rate of 92.6%.

Participants ranged in age from 26 to 45 years (M = 34.9, SD = 4.8), and were all married and living with their husbands. The majority was European American (95%). A wide range of education levels was represented. In fact, these women were more educated than their husbands, χ 2(12, N = 81) = 33.18, p < .01. Also, most women in this sample had between one and three children. The majority (57%) had two children, and only 5% had more than four children (see Table 1 for additional demographic information).

Procedure

Approximately 1 week after a letter to explain the study was sent, participants were telephoned, the purpose of the study was reiterated, and each participant’s informed consent was obtained orally. If women were available, the 15-min telephone interview was completed at that time. If not, an appointment was made.

The first interview consisted of 73 items that explored: current division of housework and childcare, ideal division of housework and childcare, desire for change, gender ideology, use of power strategies in negotiation and conflict resolution, and background information (e.g., “Are you currently employed?”). In addition, three free-response questions were included to assess what household task or aspect of childcare wives wanted their husbands to do more of, what statement wives might make to their husbands to receive assistance, and what household task or aspect of childcare the couple already divided successfully.

At the end of the first interview, each woman was asked for permission to include her name in a list of potential participants for a second interview. This request was made at the end of the telephone interview to ensure that a participant’s responses were not compromised by the knowledge that her responses could influence participation in the next stage of research. At the end of each telephone interview, participants were debriefed and thanked. Approximately 2 months after the first interview, a second 15-min telephone interview was conducted. The second interview consisted of 34 items that explored: current division of housework and childcare, desire for change, and background information. In addition, the second questionnaire included four free-response items to examine changes over time and recent discussions about childcare and housework. In these questions, each participant was given the opportunity to elaborate on the last time she and her spouse discussed how some aspect of housework or childcare would be divided, as well as any changes between her first and second interviews.

Measures

Housework and childcare

Four scales measured actual housework, ideal housework, actual childcare, and ideal childcare. The questions included in these four measures asked how specific housework and childcare tasks were divided (see Table 2). Each of these items was scored on a 7-point response scale that ranged from 1(I do it all) to 7(my spouse does it all), and a mean was calculated for each measure. Previous researchers (e.g., Coltrane, 1989; Deutsch et al., 1993; Grote & Clark, 1998; Mederer, 1993; Presland & Antill, 1987) have utilized comparable likert scales with similar items (e.g., laundry, cooking, meal preparation, feeding children, bathing children). Although some articles do not detail the reliability or validity of these scales, Deutsch et al. (1993) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 for their paternal participation in childcare measure and Grote and Clark (1998) supplied alpha coefficients of .77 for household tasks and .86 for childcare tasks.

Although factor analyses did not reveal an underlying dimension for either housework or childcare, the items in each of our categories were combined into scales. This procedure is justified because the scales were not measuring psychological dimensions but rather the cumulative behavioral actions that reflect our apriori definitions of household labor. In addition, previous research supports our decision to distinguish housework from childcare tasks (Deutsch et al., 1993; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992).

Gender ideology

Four items measured the gender ideology of women who participated in the present study. These items include: “It is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner, and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and family” (reversed); “Ideally, there should be as many women as men in important positions in the government and business”; “When both parents work full-time, fathers should be responsible for the same amount of housework and childcare as mothers”; “If a child gets sick, the husband and wife should take turns staying home from work to take care of the child.” Each item was measured on a 4-point response scale that ranged from 1(strongly disagree) to 4(strongly agree). All four items were taken from the study of Deutsch et al. (2006) about college seniors’ plans for an egalitarian marriage. Although these items produced a reliability of .68 in the study of Deutsch et al. (2006) and formed a gender ideology scale, the items did not load on the same dimension in the present sample. Therefore, they were analyzed separately.

Power strategies

Fifteen items on the first questionnaire measured participants’ power strategies. Twelve items were adapted from the study of Falbo and Peplau (1980) (ask, persuade, compromise, remind, silent, to be affectionate, pout, to have importance, hints, discuss, tell needs, reason). Participants indicated how often they used each of these strategies on 4-point response scales that ranged from 1(never) to 4(always). For example, they indicated how often they “dropped hints and made suggestions” when they and their spouses had conficts about household chores or childcare. They also indicated the frequency of an asymmetrical wife-demand/husband-withdraw interaction, an item taken from the study of Kluwer et al. (1997). Likewise, in an item developed from the research of Deutsch (1999), participants were asked how often they “explode” when having conflicts over childcare and household labor to assess women’s expression of being fed up. Lastly, participants rated how often their response to a conflict over childcare or household labor was to “avoid talking about the problem.”

A factor analysisFootnote 2 was subsequently conducted, and, based on a varimax rotation, one interpretable factor emerged from the 15 power strategies. The seven items with loading coefficients above .4 on this dimension reflect an assertive conflict resolution style. Five items loaded positively; two items loaded negatively. Those items that loaded negatively were subsequently reverse-scaled, and the seven items comprised an assertive conflict resolution style scale (see Table 3), which had an alpha reliability of .74.

Content analysis of data

Free-response items in both the first and second questionnaires were analyzed using a modified grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Analysis began with an examination of the text line-by-line; we labeled each meaning unit with a code that was inductive and came directly from the data itself. After the initial analysis, codes were renamed and redefined if necessary. Similar codes were then combined and placed into larger categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Subsequently, a thematic analysis was conducted, and themes were developed for each response that illustrated the prominent emerging patterns (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). After we developed themes for each response, overarching themes were identified, and the responses were placed into more specific categories.

Results

Initial division of labor

In line with past studies (e.g., Bianchi & Raley, 2005; Coltrane, 2000; Dempsey, 2002), we predicted and found a gendered division of labor. The tasks in both the housework and childcare scales were rated on 7-point response scales that ranged from 1(I do it all) to 7(my spouse does it all) with a midpoint of 4, which represents an equal division of tasks. One-sample t-tests confirmed the presence of inequality at Time 1 by determining that the division of housework, t(80) = −13.64, p < .01 (M = 2.54, SD = .96), and childcare, t(80) = −14.21, p < .01 (M = 2.92, SD = .68), significantly deviated from the midpoint. Women did more housework and childcare than their husbands.

At Time 1, the division of housework was positively correlated with the division of childcare, r(79) = .33, p < .01. A husband’s greater contribution to housework tasks corresponded to his greater contribution in childcare tasks. However, childcare tasks (M = 2.92) were more evenly divided than housework tasks (M = 2.54), t(80) = 3.45, p < .01.

Role of resources, structural factors, and gender ideology

Hypotheses derived from the resource, the structural factors, and the gender ideology theories, respectively, predict that wives who contribute a greater percentage of family income, work relatively more hours, and believe in liberal gender ideology will do a smaller percentage of household labor than wives who contribute relatively less in income, work relatively fewer hours, and believe in more traditional gender ideology. We conducted correlations to examine the relation between resources (wife’s percent income), structural factors (wife’s hours at work, husband’s hours at work), and gender ideology on the division of both housework and childcare. Although none of these variables were significantly related to the division of childcare responsibilities, we found some support for resources, structural factors and gender ideology as predictors of the division of housework. The percentage of a wife’s total household income was positively correlated with the division of housework, r(73) = .26, p < .05. Consistent with the resource theory, the more income a woman contributed to the family, the smaller her share of housework. Although husbands’ hours at work were not significantly related to housework allocation, r(77) = −.14, p > .05, wives’ work hours were, r(77) = .23, p < .05.Footnote 3 As predicted by the structural factors approach, the more hours a woman worked, the smaller her share of housework. Finally, only the gender ideology item “It is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner, and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and family” significantly correlated with the division of housework, r(79) = −.33, p < .01.Footnote 4 Thus, husbands performed a larger share of the housework at Time 1 if their wives disagreed with this item and were, thus, less traditional in their gender ideologies.

Role of assertiveness

In addition to the more standard theoretical predictors of the division of labor, and based on the findings of Deutsch et al. (2006), we predicted that an assertive conflict resolution style would be related to a more equal division of household labor. Correlations were conducted between the assertive conflict resolution style scale and the division of both housework and childcare at Time 1, as well as with the other predictors of domestic labor. An assertive conflict resolution style did not significantly correlate with the division of either housework, r(79) = −.01, p > .05, or childcare, r(79) = .10, p > .05. However, the assertive conflict resolution style scale negatively correlated with the wife’s relative percentage of total household income, r(73) = −.42, p < .01; the higher the wife’s percent income, the less assertive she was in conflicts regarding housework and childcare. Clearly, although women who earned a high proportion of family income did less housework, that cannot be explained by the explicit use of power, because they were less, not more, assertive than other women. When assertiveness was controlled in a partial correlation, the wife’s percentage of household income significantly correlated with the division of childcare, r(72) = .30, p < .05.Footnote 5 Thus it appears that higher income typically restrains women from behaving as assertively as other women, but when they do their income gets them a more equitable division of childcare.

Evidence that the current division of labor is unsatisfying

Ideal division of labor

Given the presence of a gendered division of labor, to what extent do women want change? When the women were asked if they had ever thought about changing the division of labor in their homes, 44 (54%) said yes, and 37 (46%) said no. Thus, in line with recent research (e.g., Johnson & Huston, 1998; Kluwer et al., 2000), a majority of women were not satisfied with their current division of labor. To examine the relation between women’s actual and ideal divisions of housework and childcare, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted between the type of tasks (housework or childcare) and division of labor (actual vs. ideal). The results indicated a significant main effect between actual and ideal division of labor, F(1, 80) = 202.44, p < .01. Participants’ ideal division of labor (M = 3.74, SD = .07) was significantly higher (i.e., closer to equal) than their actual division of labor (M = 2.73, SD = .08). In addition, a significant interaction was found between the type of household labor, namely housework and childcare, and the actual and ideal division of labor, F(1, 80) = 22.94, p < .01. Although women’s actual and ideal divisions for both housework and childcare differed, women were further from their ideal for housework (ideal M = 3.79 vs. actual M = 2.54) than for childcare (ideal M = 3.68 vs. actual M = 2.92).

Women’s aspirations were also closer to an ideal of equality for housework than for childcare. Although women’s ideal division for housework tasks (M = 3.79, SD = .99) and their ideal for childcare tasks (M = 3.68, SD = .46) did not significantly differ, t(80) = 1.15, p > .05, when we compared their ideals for each with an equal division, denoted by the midpoint of 4, their ideal housework division did not deviate significantly from an equal division, t(80) = −1.90, p > .05, but the division of childcare did, t(80) = −6.35, p < .05. Women wanted to do more than one-half of the childcare.

Discrepancies in housework and childcare

Discrepancy scores were created between an individual woman’s ideal division and her actual division of housework and childcare labor to explore further the difference between them. The discrepancy of housework was positively correlated with the discrepancy of childcare, r(79) = .33, p < .01. Women who were dissatisfied in one aspect of domestic labor tended to be dissatisfied in the other.

Correlations were conducted to evaluate the role of resources, structural factors, and gender ideology in predicting the discrepancy between a woman’s actual and ideal division of labor. These correlations showed that neither the wife’s hours at work, husband’s hours at work, wife’s percent income, gender ideology, nor the added assertive conflict resolution style scale correlated with the discrepancy of housework at Time 1. The results for the discrepancy of childcare were somewhat different. Although none of the traditional items correlated with the discrepancy of childcare, an assertive conflict resolution style did prove to have a significant negative correlation, r(79) = −.27, p < .05. The less assertive a woman was in her conflict resolution style, the further she was from her ideal division of childcare. The same held true when a partial correlation was conducted, after controlling for women’s percent income, r(70) = −.30, p < .05.

Intent to change

At Time 1, when women were asked if they actively planned to change the division of household labor in the future, 34 (43%) of them said yes, and 46 (58%) of them said no. Thus, a sizeable minority of women in fact planned for change. In addition, many women, when asked whether they actively planned to change the division of labor in their homes, referred to the active and ongoing nature of this process. For example, one woman explained:

It’s kind of a weekly thing for us here. ... Well, it’s an ongoing thing with us. I’ve told him sometimes that I’m overwhelmed with how much I have to do and he does pitch in after that but it’s only a short-term response. It doesn’t change in the long-run. There’s nothing that he does on a regular basis like daily chores or anything like that. It depends if he has time or if I tell him that I’d like him to do it because I have to work or something. Rarely does he take the initiative to do it himself.

Others offered similar expressions about the continuing battle they associated with the division of housework and childcare. One woman even went on strike to achieve change but reported that it had not succeeded as she had hoped. Yet another woman expressed a feeling that may reflect the sentiment of many women struggling to achieve a more equitable division of labor; “I’m not asking for the world; I’m just asking for him to help out like 30%.” Consistent with past studies (e.g., Kluwer et al., 1996, 2000), women in the present study were not content. The division of labor was an ongoing struggle.

Division of labor at Time 2

At Time 2, a gendered division of labor persisted. Women completed more housework, t(74) = −14.86, p < .01 (M = 2.54, SD = .85), and childcare, t(74) = −12.18, p < .01 (M = 3.14, SD = .61), than their husbands did. As at Time 1, the division of childcare at Time 2 (M = 3.14) was more equal than the division of housework (M = 2.54), t(74) = −5.29, p < .01. However, at Time 2 the division of housework and the division of childcare were no longer significantly correlated, r(73) = .14, p > .05.

Role of resources, structural factors, and gender ideology

Similar to Time 1, the Time 2 results indicate support for the relation between resources and structural factors, such as income and hours at work, and the existing division of housework but not childcare. The division of housework at Time 2 was positively correlated with both the wife’s work hours at Time 2, r(73) = .23, p < .05, and her percentage of total household income at Time 2, r(69) = .29, p < .05. The more hours the wife worked and the greater her percentage of total household income, the greater her husband’s share of housework. In addition, the husband’s work hours negatively correlated with his contribution, r(73) = −.27, p < .05. As at Time 1, the gender ideology item “It is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner, and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and family” negatively correlated with the division of housework at Time 2, r(73) = −.24, p < .05.Footnote 6

Role of assertiveness

The assertive conflict resolution style scale did not significantly correlate with either the division of housework, r(73) = .04, p > .05, or childcare, r(73) = .18, p > .05, at Time 2.

Change between Time 1 and Time 2

The division of housework and childcare at Time 2 was highly correlated with the division of housework and childcare at Time 1, r(73) = .72, p < .01, and r(73) = .74, p < .01, respectively. To examine whether change did indeed occur, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted between the type of task, namely housework and childcare, and the time at which these were evaluated. The results indicated a significant main effect for the type of task, F(1, 74) = 22.62, p < .01, which was modified by a significant interaction between the type of division of labor and the time at which these measures were evaluated, F(1, 74) = 4.83, p < .05. Although the change in housework (M = −0.01, SD = .68) was not statistically significant, t(74) = .11, p > .05, the change in childcare was (M = 0.19, SD = .47), t(74) = −3.47, p < .01. Men assumed proportionally more childcare at Time 2 than at Time 1. On average, at Time 2, women were closer to the ideal division of childcare.

Predictors of change

Role of resource, structural, and ideological variables

Partial correlations were conducted to examine the relation between variables derived from the resource, structural, and gender ideology perspectives and change in the division of household labor, and the relation between assertiveness and change in housework and childcare. We predicted that assertiveness would influence change, beyond changes predicted by percent income and/or work hours. After we controlled for the division of housework at Time 1, neither women’s percent income, nor their work hours, nor their spouses’ work hours, nor their responses to the gender ideology questions at Time 1, nor assertiveness significantly predicted housework at Time 2 (i.e., change). However, when childcare at Time 1 was controlled, the division at Time 2 significantly negatively correlated with women’s work hours at Time 1, r(64) = −.25, p < .05, and women’s percent income at Time 1, r(64) = −.30, p < .01. Therefore, at first glance, it appeared that the women who worked less and made less income at Time 1 changed toward a more egalitarian division of childcare at Time 2.

To understand this relationship, we created three categories based on the distribution of women’s percent income at Time 1: low income, 0–15% (n = 33); medium income, 20–50% (n = 39); and high income, 60–70% (n = 3). All participants were included in a category. Although there were only three high income women, it was important to examine them in a distinct category because they were the only women to earn a majority of their household’s income.

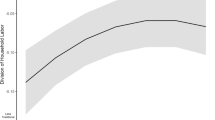

A one-way analysis of covariance, with the division of childcare at Time 1 controlled, was conducted to compare women in the three income categories on the childcare division at Time 2. This analysis highlighted that the relationship between income and change in the division of childcare is curvilinear rather than linear. Although not statistically significant, F(2, 72) = 1.60, p > .05, women in the medium income group had the most equal division of childcare at Time 2 (M = 3.26, SD = .62); women who earned the majority of their household’s income were furthest from equality (M = 2.50, SD = .82), and women in the low relative income group fell in between (M = 3.05, SD = .56). Thus, these data suggest a curvilinear relationship between women’s relative income and the division of childcare that might have been confirmed if we had had more statistical power. Bittman et al. (2003) found a similar curvilinearity for housework in their study of how spouses’ contributions to family income affect its division. Among the 14% (approximately 314) of their sample where women contributed 51–100% of household income, couples divided housework more traditionally.

Role of plans and attempts

Almost one-half (43%) of women at Time 1 indicated active plans to change the division of household labor in the future. We hypothesized that women who, at Time 1, planned to change the division of labor would be more likely than other women to attempt to change and that those who attempted change would show the greatest change. It was surprising that there was no significant relationship between women’s plan to change and their actual attempt at change, χ 2(1, N = 68) = .97, p > .05. Only 12 women both indicated a plan to change and, in fact, attempted to make a change. Thirty-eight women did something different than they had originally indicated. Twenty-two women attempted change in the absence of a stated intention to do so, and 16 women stated an intention to try to change the division of labor, but did not do so. A woman’s plan to promote change may not be an accurate measure of whether she actually will attempt to enact change in the future.

In addition, women who made an attempt to change their division of childcare were not more likely to achieve change than those who did not actively try. One-way analyses of covariance, with the division of either housework or childcare at Time 1 controlled, were conducted to compare women who attempted to change with those who did not on their division of household labor at Time 2. Ironically, a woman’s attempt to change was significantly negatively related to the change in childcare, F(1, 67) = 9.64, p < .05, but not housework, F(1, 67) = 2.20, p > .05.

Negotiating a division of labor

To gain more insight into how the division of labor is actually negotiated and changed, responses to the open-ended question “I’d like you to think back to the last time you and your spouse discussed how you were going to divide some aspect of housework or childcare, one that you wanted your husband to do more of, and tell me the story of what happened” were analyzed qualitatively. Each response was initially examined for the presence or absence of change in the division of labor, then the responses were evaluated for any underlying threads. Based upon these evaluations, three categories were formed: No Change, Limited Help, and Actual Change.

No change

There were 25 responses in the no change category. Some women in this category had attempted change but achieved nothing, and others had already given up. For example, one response in this category was: “I’d like to change it [the division of labor] but I don’t really foresee it actually changing so I’ve just stopped trying.” Other women shared this same hopeless feeling. As one explained:

I’ve given up trying to change the division of labor in my house. After years of trying I’ve given up. It’s just less stress on me if I just do it all and not even count on him to help me.

The no change category also encompassed women who believed that another division of labor was not presently possible due to structural reasons, such as their husbands’ work schedules. One woman indicated that, although change had not occurred, it might come in the future. “It [the division of labor] will only change when I change careers. ... I tell him, when I get a real job you’ll have to take her [their daughter] everywhere.” Several women expressed this same hope that the division of labor in their homes would change in the future, especially as a result of alterations in their work status. Still others did not report a change because they were happy with the division that was already in place. For example, one woman explained: “You know, it really just goes well. We don’t really have to discuss anything. We just do what we need to do and everything gets done.”

Limited help

The limited help category included 18 women who had achieved assistance by asking their husbands to accomplish a specific task. One woman stated: “We don’t really talk about it too much. If I want him to do something I just ask and he’ll do it.” Another woman reported:

Usually when I need him to do something I just say I’m gonna need help with whatever it is, picking up, etc. I just have to give him a heads up. I’m usually satisfied with the outcomes. I just have to tell him ahead of time so that he can plan his work around it.

Still other women asked and gained assistance by giving their husbands lists of what needed to be done. For example:

Childcare’s really not an issue. It’s pretty much a given. Household tasks on the other hand are the problem. It’s just easier if I give him a list of things that I want to get done. ... And as long as I give him a list then he does it and it usually gets done. If I don’t put it on the list it won’t get done. ... You have to nag or else he won’t do it.

This same woman wanted more help from her husband in making dinner, but there had not been a consistent increase in his participation. In fact, she had thought about changing her schedule to accommodate for his lack of help:

I’m actually thinking of changing to work two nights because it’s getting late for the kids to eat when I come home from working days. And if I’m not here then the meal doesn’t get cooked. So if I work nights then right after I get dinner on the table then I can leave for work.

Thus, although these women might have achieved more assistance with a specific task, the change was temporary. One particular woman indicated that a long-term change was highly unlikely: “If I asked him [her husband] to do more of something on a regular basis he would probably tell me that I’m crazy and he really does it all the time.” The division of labor remained an ongoing and daily battle for these women; they did not experience a stable change.

Actual change

The final category of how the division of labor is negotiated included 26 women who reported actual change. This fairly broad classification encompassed several subgroups of women who reported different reasons behind the changes. The four women in the first subgroup, uncertain, could not specifically explain why a change occurred. When asked to clarify how a more equal division of childcare had been achieved in her home, one woman answered: “He’s just been better.”

The next subgroup, circumstances, included eight women who indicated that the change in their division of household labor was due to alterations in household circumstances. A common example within this group resulted when the husband’s work schedule changed and subsequently increased his time spent at home. One particular woman had previously attempted to receive help in transporting the couple’s daughter to and from school, but had never achieved the assistance she requested until her husband became unemployed. She explained:

We talked about trying to work out a way for it [transporting their daughter to and from school] to be more even, even though where she goes is close to where I go. He’s home right now because he’s been laid off and he’s looking for a new job. I’ve asked that he take a bigger role in that since he’s home more. I’ve told him that it’s really to our daughter’s benefit to spend more time with him even if it’s in the car going to and from school. So he said that while he’s home he would try and do more of that and he is.

For another woman, her pregnancy sparked changes in the division of household labor:

The circumstances have changed such that I’m expecting twins and he has sort of stepped in on his own. Innately he knows that he has to do more. It was more a discussion of physical necessity. There are just certain things that I can’t do. It went well. He is doing more.

The changes described by women in this subgroup resulted from different household circumstances that promoted and even fostered a more equal division of labor. However, the circumstances that brought these women change appear to be temporary and may not result in lasting change.

Indirect, the third subgroup in the actual change classification, encompassed three women who altered their division of labor not through a direct appeal for their husbands’ participation but by indirectly involving their children. For example, one woman asked her children to approach their father for help with homework. Another had her older daughter help with chores around the house. A third woman attributed her husband’s increased help to his having overheard her complaining to her children:

I have had the general discussion with my kids more than him that I am a mom and not a maid and that I shouldn’t be the one doing everything around here...that it’s our home and not my home that they’re a guest at. So maybe by having that general conversation he has thought about it more.

The last subgroup, discussion, included 11 women who had discussions with their husbands in which they explained the reasons behind their requests. For example, one woman explained how she and her husband changed their division of taking out the garbage:

Well, like taking out the trash. I asked him to do it because it’s a lot easier for me not to have to worry about doing it. It’s one less thing for me to worry about. Since he puts the trash out on the street for the garbage men then it’s easier for him to just collect it too. So, he has done it since. He knows it helps me out.

In another example, one couple negotiated a joint decision about the husband’s contribution. The wife explained:

We mutually agreed to put it [the television] away. I might have had to give him a little nudge but now he’s doing more reading and childcare and housework because he doesn’t just come home and sit on the couch and watch it. We also took our child out of school and decided to home-school him. Before, my husband said he felt like a divorced father, and we all live in the same house, because he would only see the kids for an hour when he came home...and on the weekends. Now because we home-school the kids and put the TV away he’s spending more time with them.

The women in this subgroup either worked with their husbands to change some aspect of their division of labor or they explained to their husbands why they desired a certain change. The requests and discussions present in this category appear to reflect a more long-term tone and include women’s explanations, feelings, and motivating reasons. Perhaps these techniques assisted women in achieving and enacting their desired changes.

One woman’s description provides evidence for the potential positive effects of a discussion on the division of labor:

I asked him if he would help more with the laundry. He said yes, as he always does because he’s very agreeable with things like that. He helped me once and then that was the end of that. ... He’s a very agreeable person so when I ask him to do things he generally does that. ... I think we had an actual discussion about that [childcare] and I feel that I’m getting a little more help. Still not a lot of help, because it didn’t change a whole lot, but a little bit more. At some point I don’t intend to be home full-time so things will have to change. There is a plan that we’re going to split the work more evenly but whether that actually happens or not I don’t know.

The discussion about childcare appeared to elicit more change than her simple request for help with laundry. This particular result, however, must be interpreted with caution. Although it may provide evidence of the potential influence of a discussion, it could also reflect the very different nature of the requests. The change in childcare and not laundry is consistent with previous literature that shows that men spend more time in childcare than in housework (Bianchi & Raley, 2005).

Discussion

Presence of a gendered division of household labor

The division of both housework and childcare within the households of this sample was split along decidedly gendered lines. Women completed more housework and childcare than their husbands did. In fact, the gendered inequality persisted throughout the course of the study. This general finding supports the great majority of research that illustrates the persistence of an unequal division of household labor (e.g., Coltrane, 2000; Dempsey, 2002).

Role of resources, structural factors, gender ideology, and gender construction

The present study shows some support for the conventional theoretical perspectives of relative resources, structural factors, and gender ideology as predictors of the current division of household labor. At both Time 1 and Time 2, women who earned a greater percentage of family income and worked relatively more hours than other women completed a smaller share of housework. Likewise, at Time 2, men who worked relatively fewer hours than other men completed a greater portion of housework. In addition, at both Time 1 and Time 2 husbands completed more housework if their wives disagreed that “[i]t is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner, and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and family.”

Moreover, although speculative because of the small number of women who outearned their husbands, the curvilinear relationship between income and change in the division of childcare supports the notion that the division of labor is shaped by how men and women do gender. Women who made the majority of their household’s income also assumed most of the childcare responsibilities, whereas women who earned approximately one-quarter to one-half of the household income enjoyed the most equal division of childcare. Similarly, Tichenor (1999) found that women whose income and/or occupational status was higher than that of their husbands still completed most of the household labor, and Brines (1994) discovered that husbands who are dependent on their wives for economic support “do gender” by completing less housework. Bittman et al. (2003) found a similar curvilinearity for housework in their study of how spouses’ contributions to family income affect its division. It appears, then, that a threshold level exists; when women begin to earn a majority of the household income, the threat to conventional gender relations can be thwarted by a more conventional division of household labor.

What does assertiveness add?

Assertiveness interacted with income in complicated ways to affect the division of housework and childcare. First, we found that women who earned relatively more family income were relatively less assertive than other women. Perhaps when women’s incomes increased, the pressure to behave in more gendered ways may also have lead them to be less assertive about household labor (e.g., Bittman et al., 2003; Brines, 1994; Ferree, 1990; Tichenor, 1999) or to avoid the topic entirely because of its potential to damage the relationship. The more a wife earns relative to her husband, which threatens his breadwinning role, the greater the chances of marital discord and divorce (Brines & Joyner, 1999). By avoiding assertiveness, the high earning women may be subtly communicating that they are not going to try to convert money into power.

Alternatively, women with more income may not have needed to be assertive, at least with respect to housework. Money seemed to give them power anyway. Women’s incomes may not give them as much power as men’s, but they do give them more power than women with less income have (Blumberg, 1991). Women with more income got a more equal division, even though they were less assertive than other women. With childcare, however, income alone did not predict a more equal division of labor. In fact, none of the conventional theoretical perspectives shed light on the division of childcare in our sample. Earning more money, working more hours, and believing in liberal gender ideology were not related to a more equal division of childcare either time we interviewed our sample. Nor were they related to how close women were to their ideal divisions of childcare. However, assertiveness was important, at least the first time we interviewed women. The more assertive a woman was, the closer she was to her ideal division of childcare. In addition, when we controlled for assertiveness, higher earning wives did have a more equal division of childcare. Thus, to the extent that women were assertive, more money meant more help. Why did the effects of income depend on assertiveness for childcare, but not housework?

Differences between housework and childcare

Housework is more tedious and offers fewer rewards than childcare. A clean house is simply not as rewarding for most people as the love of a child. This difference in the relative rewards of these two domains is reflected in several aspects of our findings. Women sought equality in housework, but not childcare. Mothers may identify more closely with childcare than housework. In fact, with women’s increase in paid work since the 1960s, they have decreased the amount of time spent on housework, but continue to spend the same or more time on childcare (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000; Bianchi & Raley, 2005; Sayer, Bianchi, & Robinson, 2004). Men too seem to prefer childcare. Over the past 40 years, men have increased their involvement more in childcare than in housework (Bianchi & Raley, 2005). In our study, the division of childcare was more equal than that of housework, and men increased their contribution to childcare more over the 2 months of the study.

These differences may explain why income is differentially related to housework and childcare. Housework more clearly fits the relative resource model in which resources such as income translate into the power to opt out of responsibilities. Our finding that income independently predicts housework is consistent with past researchers who have found evidence for the effects of relative resources in housework but not childcare (Deutsch et al., 1993; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992). With respect to childcare, it is ambiguous whether women want more help unless they are clearly assertive about it. Men may think they owe their high earning wives more housework without any discussion, but may justify their lack of participation in childcare to themselves by assuming that their wives want to do a disproportionate share. By suppressing their assertiveness, high earning wives may be giving their husbands the wrong message about childcare.

Finally, assertiveness, regardless of level of income, predicted how close women were to their ideal division of childcare, but not housework responsibilities. Again, this suggests that more than material power is important in the negotiations over the less desirable housework. Women’s direct and persistent pursuit of their husbands’ help with childcare is more likely to be successful, even when wives are not high earning, because it holds potential rewards for those husbands.

Intent, attempts, and change

The path to change is not a simple one. Initially, we hypothesized that, to achieve change, a woman must recognize an unequal division of labor, form an intention to change the division, and then attempt to change it. However, women often did not do what they intended. Moreover, sometimes the division became more egalitarian even without the wife’s efforts because of a structural change in the family (e.g., a change in the husband’s work situation). Finally, women’s attempts at change did not automatically result in an egalitarian shift in either housework or childcare.

Clearly, simply making an attempt is not enough. The type of attempt and the effort involved matter. Our definition of “attempt” might have been too broad. For example, the efforts of women in the limited help category may have been too limited and short-lived. As a result, their husbands might have helped with one or two tasks without making an overall difference in the way housework or childcare was divided. In contrast, women in the discussion subgroup of actual change may have succeeded because they engaged in lengthy conversations to enact change.

A husband’s resistance or receptivity can also effectively foster or prevent any changes from taking place. Although women may try to bargain successfully for a change in the division of labor, their attempts may be thwarted by men who refuse to relinquish power or to change their beliefs and attitudes (Dempsey, 2002). The words of one participant summarize a husband’s potential to exercise this veto power. She explained: “The last time we talked about it [the division of labor] was actually when you [the interviewer] last called. I said he should clean the bathroom more and he just laughed.” In laughing, this husband was essentially stating his opposition to her request, an act that quite probably will thwart any other desires to pursue a different division of household labor. Such sentiments may reflect the entitlement that men feel and the obligation women feel in relation to housework. Because family work and childcare may be more central to a woman’s identity, and breadwinning to a man’s identity, women typically feel entitled to less help, and men to more help, at home (e.g., Hochschild, 1989; Major, 1993). Although husbands were not interviewed in the present study, they should be in future research.

Limitations

Measurement

Women who rated high on the assertive conflict resolution style scale were assumed to have had stable assertive conflict resolution styles. However, effects of assertiveness were only found the first time participants were interviewed, at the same time that assertiveness was measured. Perhaps when initially questioned about their assertiveness, participants referenced recent conversations, which may or may not have reflected their usual manner. In fact, women in the discussion subgroup, who reported on their assertive pursuit of change in the division of labor later in the study, should have scored relatively high on the assertiveness scale, if it measured a stable trait. However, women in this subgroup did not score significantly higher than other women. Given that this measure of assertiveness is new, more work is needed on its test–retest reliability and validity. If assertiveness varies over time, we may have failed to detect the effects of “assertiveness” the second time we interviewed women with the quantitative measures of the division of labor. The qualitative findings that women in the discussion-based group did report change suggest as much.

A second measurement issue involves gender ideology. The four gender ideology items we used were analyzed separately because they did not load on the same dimension. Other researchers have also found that their gender ideology items were only moderately correlated or did not all factor together (e.g., Coverman, 1985; Sanchez, 1994), which suggests that gender ideology is not a unitary construct but, rather, is composed of different components. Moreover, Kroska (1997, 2000) has argued that identity may predict behavior related to the division of household labor better than ideology does.

In our study, only the gender ideology item “It is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner, and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and family” significantly correlated with the division of household labor. Perhaps that item was more predictive of the division of labor because it relates to attitudes about domestic labor and may better capture identity than other items do. The item “Ideally, there should be as many women as men in important positions in the government and business” does not directly address the division of domestic labor. The other two items (“When both parents work full-time, fathers should be responsible for the same amount of housework and childcare as mothers” and “If a child gets sick, the husband and wife should take turns staying home from work to take care of the child”) do address housework and childcare, but both items may refer to more specific circumstances than fundamental beliefs. If circumstances require that both parents work full-time, one could believe that they should share housework and childcare equally, yet believe that ideally men and women should have a traditional division of housework and breadwinning. Their ideal beliefs may better represent their identities.

Time frame

As much literature indicates, the division of household labor is an ongoing process (e.g., Deutsch, 1999; Kluwer et al., 1996, 2000; Pittman et al., 1996) that is constantly changing, based on a couple’s daily interactions. As such, we can gain important insight by examining factors that influence the division of labor and movement toward equality within a short time frame. That being said, the short-term longitudinal design certainly limits the generalizability of our results. The links between various predictors and the division of housework and childcare may have differing effects over 6 months or 1 year. The effects of assertiveness, for example, may need more time to develop and become prominent.

The path to change

In the end, the path to change is complex. In women’s struggles for change at home they must grapple with how assertive to be, how to “do gender,” and how to contend with power issues in their marriage. Change seems to involve women’s awareness of inequality and their willingness to approach and actively promote long-term discussions with their husbands. These findings illustrate that the division of household labor is an active and ongoing process. We suggest that researchers further explore how assertiveness and other conflict-related variables work to influence the division of housework and childcare. This is a promising avenue by which researchers can better understand and illuminate how a couple achieves equality.

Notes

Married and cohabiting couples differ in the way they divide household labor (Clarkberg, Stolzenberg, & Waite, 1995; Shelton & John, 1993), the factors that affect their union stability (Brines & Joyner, 1999), and the way in which gendered power relations operate (Cunningham, 2005). For example, married women spend more time on housework than cohabiting women do (Shelton & John, 1993). None of the participants in this sample identified themselves as cohabitors.

In the factor analysis, first, the principal component analysis method was employed. Next, two factors were chosen to extract based on the component eigenvalues and corresponding scree plot. Finally, the maximum likelihood extraction method was used to extract the factors, and the varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization was used to rotate them. A loading coefficient of at least .4 was used as a cut-off.

The wife’s percentage of total household income and her number of hours at work were highly correlated, r(72) = .80, p < .01.

In a multiple regression this gender ideology item had the only significant relationship (p < .01) to the division of housework in a model, which included the gender ideology item and the wife’s percentage of total household income, adjusted R 2 = .14, F(2,72) = 6.88, p < .01.

The same did not hold true, however, for a woman’s hours at work, r(74) = .12, p > .05.

The results of multiple regression analyses indicated that, even though the housework predictors of wife’s hours at work, wife’s percentage of the total household income, husband’s hours at work, and the gender ideology item, all at Time 2, were not significant individually, some aspect of their joint effects on housework made them significant, R 2 = .14, adjusted R 2 = .09, F(4,66) = 2.71, p < .05.

References

Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 27–58.

Baxter, J. (2000). The joys and justice of housework. Sociology, 34, 609–631.

Berk, S. (1985). The gender factory: The apportionment of work in American households. New York: Plenum.

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79, 191–228.

Bianchi, S. M., & Raley, S. B. (2005). Time allocation in families. In S. M. Bianchi, L. M. Casper, & B. R. King (Eds.), Work, family, health, and well-being (pp. 21–42). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bittman, M., England, P., Folbre, N., Sayer, L., & Matheson, G. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109, 186–214.

Blumberg, R. L. (1991). The triple overlap of gender stratification, economy, and the family. In R. L. Blumberg (Ed.), Gender, family, and economy: The triple overlap (pp. 7–32). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1991). Money and ideology: Their impact on power and the division of household labor. In R. L. Blumberg (Ed.), Gender, family, and economy: The triple overlap (pp. 261–288). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brines, J. (1994). Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. American Journal of Sociology, 100(3), 652–688.

Brines, J., & Joyner, K. (1999). The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review, 64, 333–355.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values, and entrance into cohabitational versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74, 609–634.

Coltrane, S. (1989). Household labor and the routine production of gender. Social Problems, 36, 473–490.

Coltrane, S. (1990). Birth timing and the division of labor in dual-earner families: Exploratory findings and suggestions for future research. Journal of Family Issues, 11, 157–181.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208–1233.

Coltrane, S., & Adams, M. (2001). Men’s family work: Child-centered fathering and the sharing of domestic labor. In R. Hertz & N. L. Marshall (Eds.), Working families: The transformation of the American home (pp. 72–99). Berkeley. CA: University of California Press.

Conner, M., Norman, P., & Bell, R. (2002). The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychology, 21, 194–201.

Coverman, S. (1985). Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor. Sociological Quarterly, 26, 81–97.

Cunningham, M. (2005). Gender in cohabitation and marriage: The influence of gender ideology on housework allocation over the life course. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 1037–1061.

Davis, L. E., Ajzen, I., Saunders, J., & Williams, T. (2002). The decision of African American students to complete high school: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 810–819.

Dempsey, K. (1997). Trying to get husbands to do more work at home. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 33, 216–225.

Dempsey, K. C. (1999). Attempting to explain women’s perceptions of the fairness of the division of housework. Journal of Family Studies, 5, 3–24.

Dempsey, K. C. (2000). Men and women’s power relationships and the persisting inequitable division of housework. Journal of Family Studies, 6, 7–24.

Dempsey, K. (2002). Who gets the best deal from marriage: Women or men? Journal of Sociology, 38, 91–110.

Deutsch, F. M. (1999). Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Deutsch, F. M., Kokot, A. P., & Binder, K. S. (2006). College women’s plans for different types of egalitarian marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. (in press).

Deutsch, F. M., Lussier, J. B., & Servis, L. J. (1993). Husbands at home: Predictors of paternal participation in childcare and housework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1154–1166.

England, P., & Farkas, G. (1986). Households, employment, and gender: A social, economic, and demographic view. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine.

Falbo, T., & Peplau, L. A. (1980). Power strategies in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 618–628.

Fenstermaker, S., West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1991). Gender inequality: New conceptual terrain. In R. L. Blumberg (Ed.), Gender, family, and economy: The triple overlap (pp. 289–307). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ferree, M. M. (1990). Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 866–884.

Ferree, M. M. (1991). The gender division of labor in two-earner marriages: Dimensions of variability and change. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 158–180.

Grote, N. K., & Clark, M. S. (1998). Distributive justice norms and family work: What is perceived as ideal, what is applied, and what predicts perceived fairness? Social Justice Research, 11, 243–269.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking/Penguin.

Hood, J. C. (1983). Becoming a two-job family. New York: Praeger.

Ishii-Kuntz, M., & Coltrane, S. (1992). Predicting the sharing of household labor: Are parenting and housework distinct? Sociological Perspectives, 35, 629–647.

Johnson, E. M., & Huston, T. L. (1998). The perils of love, or why wives adapt to husbands during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 195–204.

Kirchler, E. (1993). Spouses’ joint purchase decisions: Determinants of influence tactics for muddling through the process. Journal of Economic Psychology, 14, 405–438.

Kluwer, E. S. (1998). Responses to gender inequality in the division of family work: The status quo effect. Social Justice Research, 11, 337–357.

Kluwer, E. S., Heesink, J. A. M., & Van de Vliert, E. (1996). Marital conflict about the division of household labor and paid work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 958–969.

Kluwer, E. S., Heesink, J. A. M., & Van de Vliert, E. (1997). The marital dynamics of conflict over the division of labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 635–653.

Kluwer, E. S., Heesink, J. A. M., & Van de Vliert, E. (2000). The division of labor in close relationships: An asymmetrical conflict issue. Personal Relationships, 7, 263–282.

Kroska, A. (1997). The division of labor in the home: A review and reconceptualization. Social Psychological Quarterly, 60, 304–322.

Kroska, A. (2000). Conceptualizing and measuring gender ideology as an identity. Gender & Society, 14, 368–394.

Major, B. (1993). Gender, entitlement, and the distribution of family labor. Journal of Social Issues, 49, 141–160.

Mederer, H. J. (1993). Division of labor in two-earner homes: Task accomplishment versus household management as critical variables in perceptions about family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 133–145.

Norman, P., Conner, M., & Bell, R. (1999). The theory of planned behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 18, 89–94.