Abstract

This research investigates whether ambivalent sexism impacts individuals’ perceptions of what is appropriate and valued dating behavior, as these perceptions may contribute to the perpetuation of traditional dating scripts. Two hundred seventeen undergraduate students from the Midwestern United States read a gender-stereotypic, gender-counter stereotypic, or egalitarian heterosexual dating vignette. Participants made judgments of appropriateness, warmth, and competence separately for the man and woman on the date. Overall, gender stereotypic dates were evaluated most positively, consistent with previous work suggesting that dating behaviors remain gendered. Evidence of the restrictive nature of the masculine gender role was obtained. Men in egalitarian and counter-stereotypic dating scenarios were evaluated negatively in terms of warmth, competence, and appropriateness, thus potentially experiencing backlash effects. Indeed, the man in the gender counter-stereotypic condition was rated as less competent, warm, and appropriate than the women, but the man in the gender stereotypic condition was rated as more competent, warm, and appropriate than the woman. Consistent with predictions, those high in ambivalent sexism had more negative reactions to gender counter-stereotypic dating scenarios than those low in ambivalent sexism. However, ambivalent sexism did not predict different reactions towards gender stereotypic and egalitarian dating scenarios, and egalitarian dates were rated as most typical regardless of participants’ ambivalent sexism. Thus, greater acceptance of gender counter-stereotypic dates was observed among those low in ambivalent sexism, and even those high in ambivalent sexism were accepting of egalitarian dating practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A wealth of research has explored heterosexual dating behaviors in the United States, with a particular focus on dating scripts, as these have implications for individuals’ own dating behavior and for the types of behaviors that are expected during a date (e.g., Eaton and Rose 2011; Rose and Frieze 1993). The content of heterosexual dating scripts remains quite gendered, despite increases in men and women’s egalitarian attitudes (Eaton and Rose 2011; Laner and Ventrone 2000). The general aim of this research is to further explore whether progress towards gender equity has been made in terms of reactions to egalitarian and counter-stereotypic dating behaviors. Importantly, the current work focuses on this issue in the context of the United States. Thus, the majority of the research outlined here was conducted using U.S. samples. However, some research using other samples is discussed when particularly relevant. The research outlined in the current work was conducted on U.S. samples unless otherwise noted.

We explore appreciation for gender equity in dating behaviors by providing individuals with descriptions of dates that vary in gender stereotypicality and allowing them to make evaluative judgments regarding these dates. This approach differs from traditional work in this domain that uses a script method, asking individuals to generate descriptions of typical dating behaviors (Moor Serewicz and Gale 2008; Rose and Frieze 1993). The procedure employed in this research is useful in that instead of simply asking participants to describe a typical date, it involves the presentation of a variety of different dates and asks participants to evaluate them. In other words, this procedure, unlike the typical script method, allows us to look at gender equality in dating behaviors in terms of potential backlash, or negative evaluations of gender counter-stereotypic behaviors (Rudman 1998; Rudman and Fairchild 2004).

We further explore whether progress towards gender equity has been made in terms of perceptions of dating behaviors by investigating whether ambivalent sexism, a constellation of positive attitudes towards traditional women and negative attitudes towards non-traditional women, impacts individuals’ perceptions of what is appropriate dating behavior (Glick and Fiske 1996). Previous research demonstrating the continued gendered nature of dating behaviors is unexpected given increased trends towards endorsement of egalitarian norms (Eaton and Rose 2011). We directly investigate whether trends towards greater acceptance of gender equality in dating behaviors may be seen in individuals who endorse less traditional gender norms—those low in ambivalent sexism.

Investigating perceptions of dating behaviors is essential, as these perceptions relate to important outcomes such as dating behaviors (Rose and Frieze 1993) and beliefs about the appropriateness of behaviors that follow the date, such as sexual interactions (Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). Dating scripts affect how people act out gender early in heterosexual relationships, and these behaviors can form the basis for later relationships, resulting in the perpetuation of gendered power differentials, behaviors, and stereotypes (Rose and Frieze 1993). The current work adds to our existing knowledge about gender issues by exploring whether reactions to dating behaviors are moderated by ambivalent sexism. Little previous research has explored individual difference moderators of reactions to dating behaviors, and this is informative because of what it can tell us about acceptance of gender equality in dating behaviors. Previous research has concluded that dating scripts remain particularly gendered (Eaton and Rose 2011), and although we do not challenge this general finding, we suggest that appreciation for gender equality in dating behaviors may be seen in particular subsets of individuals, such as those low in ambivalent sexism. The role of ambivalent sexism in moderating reactions to dating behaviors may be of interest to readers of many cultures, as although specific dating behaviors and values may differ across cultures, previous theory and research suggests that ambivalent sexism functions similarly across cultures (Chen et al. 2009, Glick et al. 2000). The current work also makes a novel contribution by investigating reactions to egalitarian dates. These reactions can also help assess the acceptance of gender equity in dating behaviors.

Thus, the present work had two related goals: to further explore whether progress towards gender equity has been made in the dating realm by measuring reactions to dates that vary in their gender stereotypicality, and to investigate whether ambivalent sexism moderates these reactions. In order to achieve these goals we presented individuals with three different dating scenarios: gender stereotypic, gender counter-stereotypic, or egalitarian. Individuals were then asked to rate the dating scenario and the described couple along a variety of evaluative dimensions. Participants also completed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory.

Ambivalent Sexism Theory

The current work is grounded in ambivalent sexism theory, which posits that gender inequity remains in part because individuals do not hold universally negative attitudes towards women, but a constellation of both positive and negative attitudes that justify the gender status quo (Glick and Fiske 2002). Thus, ambivalent sexism is composed of two related types of gendered beliefs, hostile and benevolent. Hostile sexism is a set of negative attitudes about women that are primarily directed at nontraditional women. Benevolent sexism is a set of positive attitudes towards traditional women that restrict women’s roles, and include ideas such as protective paternalism, the belief in the importance of protecting and helping women (Glick and Fiske 1996).

Thus, a key aspect of ambivalent sexism that distinguishes it from other measures of traditional views about gender relations is the idea that individuals simultaneously hold both positive and negative attitudes towards women, and that these coexisting beliefs are mutually supporting. These ambivalent attitudes maintain and justify the gender status quo by directing negativity towards gender counter-stereotypic women and positivity towards gender stereotypic women (Glick and Fiske 1997). For example, hostile sexism is related to negative evaluations of career women, whereas benevolent sexism is related to positive evaluations of homemakers (Glick et al. 1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism are significantly positively correlated cross-culturally, and both are negatively related to national indices of gender equality (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2001; Glick et al. 2000).

Ambivalent sexism plays a role in a variety of circumstances, but most important for the present study is related to behaviors and preferences in heterosexual relationships. Research suggests that ambivalent sexism predicts romantic partner prescriptive and proscriptive ideals related to wanting a traditional partner in samples from the U.S. (Lee et al. 2010) and New Zealand (Sibley and Overall 2011; Travaglia et al. 2009). Ambivalent sexism also affects marriage norms and mate selection (Chen et al. 2009), and the functioning of close relationships during conflict in a sample from New Zealand (Overall et al. 2011).

However, to our knowledge research has not investigated the role of ambivalent sexism in perceptions of dating scripts. The current work suggests that ambivalent sexism also predicts backlash towards gender counter-stereotypic dating behaviors. Knowledge of how ambivalent sexism in particular affects perceptions is important for a number of reasons. As previously mentioned, ambivalent sexism plays a role in a variety of circumstances related to heterosexual romantic relationships (e.g., Chen et al. 2009; Glick and Fiske 2002). Additionally, ambivalent sexism is a contemporary measure of gender attitudes that has generated a wealth of research. Finally, previous work suggests that different measures of gendered beliefs may be best suited to predict different types of outcomes. Indeed, the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory may be better suited to circumstances involving men and women’s interpersonal relationships, whereas other measures such as the Attitudes toward Women Scale may be better suited to other circumstances such as predicting political attitudes regarding gender equality (Glick and Fiske 1997). Thus, as heterosexual dates are interactions between men and women, ambivalent sexism may be especially likely to play a role in reactions to dating scripts.

Notably, the current work focuses on ambivalent sexism, the combination of both hostile and benevolent sexism. We do so for two reasons. First, we focus on ambivalent sexism because it is an overarching constellation of beliefs that endorse traditional gender roles. Indeed, hostile and benevolent sexism are correlated with one another, and mutually support one another to justify the gender status quo (Glick and Fiske 1997). Consistent with this reasoning, previous research refers to ambivalent sexism as a motivated cognitive style, one which impacts the general way individuals view the world (Roets et al. 2012). Second, we focus on ambivalent sexism because we make similar predictions about the role of hostile and benevolent sexism in predicting reactions towards gender counter-stereotypic dating behaviors. Hostile sexism is particularly relevant in predicting negative reactions to gender counter-stereotypic dating behaviors, as it is directed toward counter-stereotypic behavior. Benevolent sexism is particularly relevant in predicting negative reactions to gender counter-stereotypic dating behaviors, as it is especially relevant in predicting reactions in close relationships. Indeed benevolent sexism includes a stress on the importance of traditional heterosexual intimacy, and protective paternalism, a belief in the importance of protecting women that is related to chivalry (Viki et al. 2003). Thus, the current work focuses on ambivalent sexism, the combination of both hostile and benevolent sexism.

Perceptions of Dating Behaviors

The majority of research on heterosexual dating behaviors has focused on dating scripts. Scripts are ordered cognitive structures that provide a guide for the appropriate nature and sequence of events (Abelson 1981). Thus, dating scripts are a collection of sequential content regarding what happens on a date, or a public expression of romantic interest in which the two interested parties spend time getting to know each other (Eaton and Rose 2011). Dating script research often asks participants to generate open-ended responses regarding what happens on a date. For example, Bartoli and Clark (2006) asked participants to describe how dates are initiated, what couples do on dates, and how dates end. This research suggests that a typical dating script involves both parties talking about shared interests during an activity, often a meal.

The more specific elements of heterosexual dating scripts are still quite gendered, despite men and women’s growing appreciation for gender equity (Eaton and Rose 2011; Laner and Ventrone 2000). When asked to describe typical heterosexual dates, people still describe men and women engaging in different behaviors. Men and women both report that a typical date involves a man asking the woman out, deciding on the plans, picking up his date, holding doors for his date, and paying the bill (Bartoli and Clark 2006; Laner and Ventrone 2000; Moor Serewicz and Gale 2008; Rose and Frieze 1993). These gender differences suggest that men should take active roles in dating (Laner and Ventrone 2000; Morgan and Zurbriggen 2007; Rose and Frieze 1993). Women are expected to engage in more passive, reactive roles, such as perfecting their physical appearance, engaging in emotional disclosure, and resisting sexual advances (Bartoli and Clark 2006).

These gendered dating roles are consistent with U.S. gender stereotypes. Competence and warmth are two fundamental dimensions along which people vary (e.g., Fiske et al. 2006). Competence encompasses self-focused traits such as confidence and assertiveness. Warmth encompasses more reactive, other-focused traits such as kindness and sympathy. Men are believed and expected to be relatively more competent, whereas women are believed and expected to be relatively more warm (e.g., Eagly 1987). The active roles men play in a gender stereotypic date demonstrate competent traits, whereas the passive roles women play demonstrate warm traits.

These stereotypes and gendered dating roles are also often prescriptive. People believe that men and women’s actions should be consistent with these gender stereotypes, and those who are not face economic and social penalties, known as backlash effects (Rudman 1998; Rudman and Fairchild 2004). Research suggests that most college students still believe the man should always initiate a date, and men report asking for dates more often than women (Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). Also, women who initiate dates are rated more negatively than men who initiate dates (Green and Sandos 1983).

The Importance of Studying Dating Behaviors

Studying perceptions of dating behaviors is important because these perceptions are related to a variety of downstream outcomes. In particular, scripts have been a popular topic of research because people report that their own dating experiences are very similar to these scripts (Rose and Frieze 1993). Indeed, gender roles are hypothesized to be especially salient in early stages of relationships (Levinger 1983). Enacting prescribed gender roles may reduce anxiety, as these roles rely on convention and mutual knowledge and reduce uncertainty regarding appropriate behavioral responses (Eaton and Rose 2011). Using dating scripts to guide one’s behavior may also be an impression management strategy, as doing so may suggest that one is socially skilled and savvy about cultural norms (Eaton and Rose 2011; Rose and Frieze 1993). Heterosexual dating norms may both reflect and perpetuate more global societal gender norms as these initial behaviors help set the stage for the gender role expectations for the rest of the relationship (Eaton and Rose 2011). Thus, transforming the gendered patterns of power inherent in dating scripts may be an essential step towards gender equity in heterosexual relationships.

The gendered nature of dating behaviors is also important to investigate because what happens on a date affects perceptions of appropriate subsequent behavior. For example, men are more likely than women to expect sexual interactions on a first date, especially when the man paid for the date (Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). This research also suggests that men report higher rape myth acceptance when the woman initiated and paid for the date, perhaps due to increased sexual expectations and the perception that the invitation for the date includes an invitation for physical intimacy (Bostwick and DeLucia 1992). Thus, unfortunately, women may be in a lose-lose situation when it comes to dating scripts and the expectation for engagement in sexual activity.

Given the importance of studying perceptions of dating behaviors, researchers have explored what moderates these perceptions. For example, men and women generally agree on the nature of dating scripts (Bartoli and Clark 2006; Rose and Frieze 1993). However, there is some evidence of gender differences for reactions to sexually suggestive behavior in a Canadian sample, with men classifying these behaviors as elements of a good date, but women classifying these behaviors as elements of a bad date (Alksnis et al. 1996). Additionally, other factors such as age, ethnicity, sexual experience, and involvement in sororities and fraternities may also affect dating perceptions, especially with regard to the potential sexual component of the date (Bartoli and Clark 2006; Ross and Davis 1996). Relatively little work has explored the role of individual differences in what is considered appropriate or desirable dating behavior. The current work makes a novel contribution by exploring the role of ambivalent sexism in moderating perceptions of dating behaviors.

The Present Study

The purpose of this research is twofold. First, we investigate whether progress towards gender equity in perceptions of dating behaviors has been made using a method that assesses backlash, by measuring individuals’ evaluations of dates that vary in gender stereotypicality. Second, we investigate the role that ambivalent sexism plays in perceptions of dating behaviors, proposing that there are trends towards gender equity, at least among individuals with less traditional gender attitudes.

Participants were presented with one of three dating scenarios that reflect the typical dating script of going out to eat and vary in their gender stereotypically (gender stereotypic, gender counter-stereotypic, and egalitarian), and asked to make evaluative judgments regarding the described behaviors. Although dating scripts are still gendered in nature, people have become more explicitly egalitarian, yet relatively little is known about reactions to egalitarian dates (Eaton and Rose 2011). Thus, of particular interest were participants’ responses to the egalitarian dating scenario. However, given the lack of research on reactions to egalitarian dating situations, we did not make a priori hypotheses regarding participants’ responses in this condition. A priori hypotheses were only made regarding responses to the gender stereotypic and gender counter-stereotypic scenarios.

In order to assess the effectiveness of the manipulation of date gender stereotypicality, we included two manipulation checks: ratings of dominance and typicality. First, as the balance of power and authority differentiates gender stereotypic, egalitarian, and gender counter-stereotypic relations, the male target was expected to be rated as most dominant in the gender stereotypic condition, followed by the egalitarian condition, and then followed by the gender counter-stereotypic condition. Second, as the typicality or normative nature of the date differs across gender stereotypic vs. gender counter-stereotypic dates, the gender stereotypic scenario was expected to be perceived as more typical than the gender-counter stereotypic scenario.

We anticipated that men and women would respond similarly to these dating scenarios. Previous research suggests that few gender differences exist in the perceptions of dating behaviors (Bartoli and Clark 2006; Rose and Frieze 1993). In addition, research on backlash towards gender counter-stereotypic behavior also obtains few participant gender effects (Rudman and Glick 2008). However, we do expect that men will score higher in ambivalent sexism than will women (Hypothesis 1), consistent with previous research (Glick and Fiske 1996). We also explore whether there are any additional participant gender effects by including participant gender in all analyses.

Our primary hypotheses concern participants’ evaluative judgments of the date and targets. We predicted that participants would feel more negatively about the gender counter-stereotypic condition than the gender stereotypic condition (Hypothesis 2). This prediction is consistent with theories of backlash, which suggest that counter-stereotypic behavior is reacted to negatively (Rudman 1998). Backlash plays an important role in maintaining stereotypes and the status quo by punishing counter-stereotypic behavior. Fear of future backlash can ensue, and elicit future gender conformity and attempts to hide gender counter-stereotypic behaviors (Rudman and Fairchild 2004).

Backlash effects come in a variety of forms, and in this research we explore negative reactions to counter-stereotypic behavior in terms of appropriateness, warmth, and competence. As counter-stereotypic behavior violates ingrained expectations about typical and desired behavior, an initial negative evaluation to counter-stereotypic behavior is one of inappropriateness. Thus, we predicted participants would rate targets on gender counter-stereotypic dates as less appropriate than those on gender stereotypic dates (Hypothesis 2a). Some of the most commonly investigated backlash effects are negative social reactions that come in the form of dislike (Rudman 1998; Rudman and Glick 2001). In this vein, we measured positive social reactions to targets in the form of warmth, a fundamental dimension along which both people and stereotypes vary (Fiske et al. 2006). We predicted that participants would rate targets on gender counter-stereotypic dates as less warm than those on gender stereotypic dates (Hypothesis 2b). For completeness, we also investigated competence ratings, the other basic dimension along which people and stereotypes differ (Fiske et al. 2006). Backlash research has demonstrated that counter-stereotypic behavior also has negative consequences with regard to outcomes related to competence, such as hireability (Brescoll and Uhlmann 2008). Enacting counter-stereotypic behavior may also negatively impact competence ratings, as the ability to enact socially acceptable behaviors may be seen as a form of social skills or competence (Eaton and Rose 2011; Rose and Frieze 1993). Thus, we predicted that participants would rate targets on gender counter-stereotypic dates as less competent than those on gender stereotypic dates (Hypothesis 2c).

We also predicted that participants’ ambivalent sexism would interact with scenario type when asked to make these evaluative judgments. The likelihood that an individual reacts negatively to behavior should be influenced not only by the extent to which that behavior is stereotypic or counter-stereotypic in terms of cultural expectations, but also by that individual’s own attitudes and expectations about what types of behavior are appropriate and desirable (Rudman and Glick 2008). As ambivalent sexism is a set of beliefs that influences the types of behaviors individuals view as appropriate and desirable for men and women (Glick and Fiske 1996; Roets et al. 2012), those high in ambivalent sexism are especially likely to react negatively to gender counter-stereotypic behavior only (Hypothesis 3). As gender counter-stereotypic behavior is especially likely to violate high ambivalent sexists’ ingrained expectations about typical and desired behavior, we expected that ambivalent sexism would be negatively associated with ratings of targets’ appropriateness in the gender counter-stereotypic scenario (Hypothesis 3a). We also explored warmth ratings, as dislike should be elicited when one evaluates behaviors that violate not only cultural expectations, but one’s own expectations as well (Rudman 1998). Thus, we expected that ambivalent sexism would be negatively associated with ratings of targets’ warmth in the gender counter-stereotypic scenario (Hypothesis 3b). Finally, when behavior violates cultural norms and one’s own expectations, negative evaluations of competence should ensue (Brescoll and Uhlmann 2008), in part because the ability to enact socially accepted behaviors is seen as an indication of social competence (Eaton and Rose 2011; Rose and Frieze 1993). Thus, we expected that ambivalent sexism would also be negatively associated with ratings of targets’ competence in the gender counter-stereotypic scenario (Hypothesis 3c).

Finally, we predicted that target gender would interact with scenario type for these judgments. As the masculine role may be particularly inflexible (e.g., Sandnabba and Ahlberg 1999), impressions of male targets may be more negative than impressions of female targets in the gender counter-stereotypic condition. Stereotypically masculine roles and behaviors hold more value and status than stereotypically feminine roles and behaviors. Thus, when men enact counter-stereotypic behaviors, not only are they enacting counter-stereotypic behaviors but they are also enacting low status behaviors, and so may be particularly likely to experience backlash. On the other hand, stereotypic behavior may be especially valued in men. For example, as research on U.S., Dutch, and German samples suggests that people feel generally positively about chivalry (Barreto and Ellemers 2005; Bohner et al. 2010; Kilianski and Rudman 1998), impressions of male targets may be more positive than impressions of female targets in the gender stereotypic condition. Therefore, in the gender counter-stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated more negatively than women, but in the gender stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated more positively than women (Hypothesis 4).

In particular, we expect that ratings of appropriateness, warmth, and competence will depend on the interaction between condition and target gender. As the male role is particularly rigid, in the gender counter-stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as less appropriate than women, but in the gender stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as more appropriate than women (Hypothesis 4a). Men may also be especially likely to experience backlash in the form of dislike for engaging in counter-stereotypic behavior, as there is generally less acceptance of men’s enactment of low status, counter-stereotypic behavior. In addition, previous research suggests that individuals are especially likely to favor men who engage in stereotype consistent behaviors such as chivalry (Kilianski and Rudman 1998). Thus, in the gender counter-stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as less warm than women, but in the gender stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as more warm than women (Hypothesis 4b). Finally, as the male role is particularly restrictive, a man enacting gender counter-stereotypic behavior may be especially likely to be perceived as lacking social competence. Thus, in the gender counter-stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as less competent than women, but in the gender stereotypic condition men were expected to be rated as more competent than women (Hypothesis 4c).

In sum, we made three primary predictions regarding perceptions of dating behaviors. We predicted that participants would rate targets on gender stereotypic dates as more appropriate, warm, and competent than those on gender counter-stereotypic dates (Hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c respectively). Additionally, we predicted that participants’ ambivalent sexism would be negatively related to ratings of appropriateness, warmth, and competence in the gender counter-stereotypic scenario only (Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c respectively). Finally, we predicted that male targets would be rated as less appropriate, warm, and competent than female targets in the gender counter-stereotypic condition, but male targets would be rated more appropriate, warm, and competent than female targets in gender stereotypic condition (Hypotheses 4a, 4b, and 4c respectively). Although we do not expect these effects to be moderated by participant gender, we do expect that men will score higher in ambivalent sexism than will women (Hypothesis 1).

Method

Participants & Design

Two-hundred and seventeen college students participated in exchange either for partial course credit (204) or for course extra credit (13) in introductory psychology courses. In order to clearly identify the sample as consisting of young undergraduates, three participants were excluded who were 30 years or older. Additionally, in order to keep the sample as homogenous as possible, we excluded 38 self-identified Asian/Pacific Islander participants whose native language was not English given that the goal of this research was to explore perceptions of U.S. dating scripts, and cultures vary in terms of their gender socialization experiences and relationship behaviors (e.g., Chaing et al. 2012).

The final sample consisted of 176 participants (90 female; M age = 19.26, SD = 1.33). The majority of participants identified as Caucasian (79.5 %). The remaining participants identified as African American (4 %), Asian (4 %), Hispanic (2.8 %), and as having multiple ethnic backgrounds (9.7 %). Data were collected May–July 2012 (65 participants) and September–October 2013 (111 participants). The second sample of participants was collected in response to reviewer concerns about adequate power. Importantly, there are no differences in the pattern of results across these two time periods. Data collection time period was included as a factor in every analysis below, however few significant effects involving data collection time period were obtained.

Participants were randomly assigned to view one of three dating vignettes (gender stereotypic, gender counter-stereotypic, or egalitarian), and tested individually. Fifty-nine participants were in the gender stereotypic condition (29 female), 61 participants were in the egalitarian condition (29 female), and 56 participants were in the gender counter-stereotypic condition (32 female). Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for these demographic variables separately by condition and participant gender. There are no significant differences across conditions in terms of participant gender, age, or race.

Procedure

Participants signed up for a study presented as investigating situational judgments and attitudes. Upon arriving at the laboratory, participants were consented and presented with one of three dating vignettes: gender stereotypic, gender counter-stereotypic, or egalitarian. These vignettes described a Friday-night date in which a heterosexual couple went to dinner together. The gender stereotypic condition described a typical U.S., gendered dating script (e.g., Laner and Ventrone 2000; Rose and Frieze 1993). In the gender stereotypic condition, the man engaged in seven chivalrous behaviors including driving to pick up his date, holding the restaurant door for his date, pulling out his date’s chair, paying the bill, and offering his date his jacket (for the complete vignettes refer to Appendix). In the gender counter-stereotypic condition, the woman engaged in these same chivalrous behaviors for her date, with two exceptions. To minimize demand effects and suspicion about our manipulation, the woman was not described as pulling out the seat for her date or as offering her date her jacket. In the egalitarian condition, behaviors described as chivalrous in previous conditions were either not described, or described as a function of joint action by both the woman and man. For example, no door holding was described, and both participants paid the bill.

Participants then completed ratings of the situation and the individuals involved. Participants rated the man and woman separately on 11-point semantic differential scales intended to measure competence: incompetent to competent, knowledgeable to ignorant, capable to incapable, and unintelligent to intelligent (averaged and reverse-coded when necessary to form a competence composite, α = .87, .75 for male and female targets respectively). Participants also rated the man and woman separately on 11-point semantic differential scales intended to measure warmth: cold to warm, likeable to not likable, unfriendly to friendly, and good-natured to ill-natured (averaged and reverse-coded when necessary to form a warmth composite, α = .86, .86 for male and female targets respectively). Participants were also asked to make separate ratings of how appropriate the man and woman’s behavior was on 7-point scales from “not at all” to “extremely.”

Participants also completed two manipulation checks. We asked participants to respond to a single item in which they indicated who was more dominant in the described relationship on scale ranging from 1 (the woman is dominant) to 7 (the man is dominant). We also asked participants to rate how typical the scenario was on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely).

Participants also completed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1996), which includes 22 items (e.g., “Women should be cherished and protected by men” and “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men”). Participants responded on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). These items were averaged after reverse-coding when necessary to form the ambivalent sexism composite (α = .82). The ambivalent sexism composite was centered and analyzed as a continuous predictor in all analyses. Analyses were conducted with the benevolent and hostile subscales of ambivalent sexism separately, but as the results remain similar across these analyses, we only report analyses involving the entire ambivalent sexism composite for the sake of concision. Finally, participants were fully debriefed.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics for each manipulation check and dependent variable separately by condition, participant gender, and target gender. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, men scored higher on ambivalent sexism (M = 3.67, SD = .56) than did women (M = 3.49, SD = .61), t(174) = 1.96, p = .05. Participant gender was included as a factor in every analysis below. Even though no other main effects or interactions involving subject gender are significant in our analyses, participant gender was retained as a factor in these analyses.

Manipulation Checks

Multivariate Analysis

A between-subjects MANOVA was conducted on our two manipulation checks using condition, participant gender, and data collection time period as categorical between-subjects predictors and participants’ ambivalent sexism score (centered) as a continuous between-subjects predictor. This analysis strategy is analogous to a regression approach and is consistent with the analysis strategy employed in previous research (e.g., Appel and Mara 2013; Wesselmann and Kelly 2010). One advantage of this procedure is that it allows ambivalent sexism to be treated as a continuous predictor, without requiring two dummy codes for condition (which has three levels), resulting in a more clear interpretation of the results.

Two significant main effects were obtained. A significant omnibus main effect of data collection time period, F(2, 151) = 3.50, p = .05, ηp 2 = .04, and a significant omnibus main effect of condition, F(4, 304) = 44.86, p < .001, ηp 2 = .37, were obtained. No other multivariate main effects or interactions reached significance, including all effects involving participant gender, both main effects and interactions. The significant omnibus effects obtained in the MANOVA were followed-up with separate univariate analyses on dominance and typicality ratings separately. As in the multivariate analyses, condition, participant gender, and data collection time period were entered as categorical between-subjects predictors and participants’ ambivalent sexism score (centered) was entered as a continuous between-subjects predictor.

Univariate Analyses

The univariate main effect of data collection time period was nonsignificant for dominance ratings, F(1, 152) = .20, p = .65, but significant for typicality ratings, F(1, 152) = 6.98, p = .01, ηp 2 = .04. Overall, participants in the second data collection time period rated the scenarios as more typical (M = 3.91) than participants in the first data collection time period (M = 3.28). As no other main effects or interactions with data collection time period emerge in our analyses, we are reluctant to make much of this single finding. Importantly, there are never interactions with data collection time period, indicating that the effects we observe hold for both data collection time periods.

The univariate main effect of condition was significant for both dominance ratings, F(2, 152) = 68.85, p < .001, ηp 2 = .48, and typicality, F(2, 152) = 54.73, p < .001, ηp 2 = .42. Ratings indicated the highest level of male dominance in the gender stereotypic condition (M = 4.91), followed by the egalitarian condition (M = 4.02), and then gender counter-stereotypic condition (M = 1.87). Least significant difference post hoc comparisons indicate that each of these means are significantly different from one another, ps < .001. Thus, these results suggest that the scenarios successfully manipulated the gender role stereotypicality of the date, and are consistent with our predictions that the male target would be rated as most dominant in the gender stereotypic scenario, followed by the egalitarian condition, and then followed by the gender counter-stereotypic condition.

Ratings of typicality were highest for the egalitarian condition (M = 4.92), followed by the gender stereotypic condition (M = 3.80), and then gender counter-stereotypic condition (M = 2.05), and least significant difference post hoc comparisons indicate that each of these means are significantly different from one another, ps < .001. Thus, these results suggest that the scenarios successfully manipulated the gender role stereotypicality of the date. Consistent with expectations, the gender stereotypic scenario was rated as more typical than the gender counter-stereotypic scenario. Notably, these results also demonstrate that participants perceive the egalitarian scenario as the most typical scenario. This finding is consistent with the general perception that dating has become more egalitarian, even though these perceptions seem to overestimate the amount of progress that has been made towards gender equity in dating (e.g., Eaton and Rose 2011). In sum, the results of the manipulation checks provide evidence that the scenarios successfully manipulated the gender stereotypically of the date, as scenario condition affected participants’ ratings of dominance and typicality.

Primary Analyses

Multivariate Analysis

A repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted on our primary dependent variables (appropriateness, warmth, and competence) using condition, participant gender, and data collection time period as categorical between-subjects predictors, participants’ ambivalent sexism score (centered) as a continuous between-subjects predictor, and target gender as a within-subjects predictor. This procedure is comparable to a regression approach and allows ambivalent sexism to be treated as a continuous predictor, without requiring two dummy codes for condition.

Only four significant effects were obtained. A target gender omnibus main effect was obtained, F (3, 150) = 10.50, p < .001, ηp 2 = .17, in which participants generally made more positive ratings of the female target than the male target. Hypothesis 2 predicted that participants would feel more positively about the gender stereotypic condition than the gender counter-stereotypic condition. Consistent with this prediction, an omnibus main effect of condition was obtained, F (6, 302) = 15.82, p < .001, ηp 2 = .24. Hypothesis 3 predicted that ambivalent sexism would be associated with more negative evaluations in the gender counter-stereotypic scenario only. Consistent with this prediction, an omnibus interaction between condition and ambivalent sexism was obtained, F (6, 302) = 2.66, p = .02, ηp 2 = .05. Finally, Hypothesis 4 predicted that in the gender counter-stereotypic condition men would be rated less positively than women, but in the gender stereotypic condition men would be rated more positively than women. Consistent with this prediction, an omnibus interaction between condition and target gender was obtained, F (6, 302) = 14.83, p < .001, ηp 2 = .23. No other multivariate main effects or interactions reached significance. Thus, perhaps of particular interest to this readership, we did not obtain significant main effects or interactions with participant gender.

All hypotheses were supported when analyzing hostile and benevolent sexism separately. The significant effects obtained in the MANOVA were probed with repeated-measures univariate ANOVAs below, in which appropriateness, warmth, and competence were analyzed separately using condition, participant gender, and data collection time period as categorical between-subjects predictors, participants’ ambivalent sexism score (centered) as a continuous between-subjects predictor, and target gender as a categorical within-subjects predictor.

Hypothesis 2: Condition Main Effects

A significant main effect of condition was obtained on appropriateness, warmth, and competence. Table 3 summarizes these univariate condition main effects. Ratings were most favorable for the gender stereotypic condition, followed by the egalitarian condition, and then the gender counter-stereotypic condition. Least significant difference post hoc comparisons indicate that for all dependent variables, each of these means are significantly different from one another, ps < .01. These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 2, which predicts participants would feel more positively about the gender stereotypic condition than the gender counter-stereotypic condition in terms of appropriateness (2a), warmth (2b), and competence (2c).

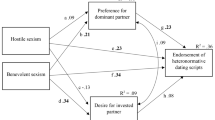

Hypothesis 3: Condition × Ambivalent Sexism Interactions

Significant interactions between condition and ambivalent sexism were obtained on appropriateness, warmth, and competence. Table 4 summarizes these univariate condition and ambivalent sexism interactions. These interactions were probed by conducting separate linear regressions for each condition using ambivalent sexism (centered) as the predictor, which allowed us to continue to treat ambivalent sexism continuously. Ambivalent sexism was unrelated to ratings of appropriateness, warmth, and competence in the gender stereotypic and egalitarian conditions. Ambivalent sexism was negatively related to ratings of appropriateness, warmth, and competence in the gender counter-stereotypic condition (ps < .01). Table 5 summarizes these regression analyses probing the interactions between condition and ambivalent sexism. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 3, which predicted that ambivalent sexism would be negatively related to target ratings only in the gender counter-stereotypic condition in terms of appropriateness (3a), warmth (3b), and competence (3c).

Target Gender Main Effects

A significant univariate main effect of target gender was obtained on warmth and competence ratings only. Table 6 summarizes these univariate target gender main effects. Female targets were generally rated more favorably than male targets, as they were rated as more warm and competent. Appropriateness ratings did not differ significantly by target gender. Importantly, the multivariate main effect of target gender was qualified by an interaction with condition.

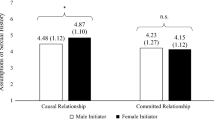

Hypothesis 4: Target Gender × Condition Interactions

Significant interactions between target gender and condition were obtained on appropriateness, warmth, and competence. Table 7 summarizes these univariate target gender and condition interactions. These interactions were probed by conducting post-hoc paired samples t-tests separately by condition. In the gender counter-stereotypic and egalitarian conditions, female targets were rated are more appropriate, warm, and competent than male targets (ps < .01). However, in the gender stereotypic condition, male targets were rated as more appropriate, warm, and competent than female targets (ps < .01). Table 8 summarizes these analyses probing the interactions between target gender and condition. These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 4, which predicts that in the gender stereotypic condition participants would feel more positively towards the male target than the female target, but in the gender counter-stereotypic condition participants would feel more positively towards the female target than the male target. Support was obtained for Hypothesis 4 with regards to ratings of appropriateness (4a), warmth (4b), and competence (4c).

Discussion

The results of this research provide insight into U.S. individuals’ perceptions of gender stereotypic, gender counter-stereotypic, and egalitarian dates, and the degree to which progress has been made towards gender equity in these perceptions. As expected, men scored higher in ambivalent sexism than women, supporting Hypothesis 1. This represented our only significant participant gender effect; all other main effects and interactions with participant gender did not reach significance. The results also suggest that overall participants felt more positively about the gender stereotypic condition than the gender counter-stereotypic condition, supporting Hypothesis 2. Indeed, targets were rated as more appropriate (2a), warm (2b), and competent (2c) in the gender stereotypic condition than in the gender counter-stereotypic condition. These findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that gendered dating roles are prescriptive (Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010; Green and Sandos 1983) and previous research demonstrating backlash effects for enacting counter-stereotypic behaviors (Rudman 1998; Rudman and Fairchild 2004). Thus, the gendered patterns of power in dating scripts continue to reflect gender power relations more generally, perhaps in part because these initial behaviors set the stage for gender role expectations throughout relationships (Eaton and Rose 2011; Rudman and Fairchild 2007).

The current work provides novel evidence that differences in ambivalent sexism are indeed related to perceptions of what is appropriate and desirable dating behavior. Participants high in ambivalent sexism felt more negatively about the gender counter-stereotypic condition than participants low in ambivalent sexism. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, ambivalent sexism was negatively related to ratings of target appropriateness (3a), warmth (3b), and competence (3c) in the gender counter-stereotypic condition. Thus, the current work provides evidence that ambivalent sexism, an index of traditional gendered attitudes, affects U.S. individuals’ perceptions of what is appropriate and valued dating behavior, contributing to the perpetuation of traditional dating scripts.

The current work also explored how U.S. individuals’ judgments of the same heterosexual dating scenario may differ depending on target gender. Although main effects of target gender were obtained in which the female target was generally rated more positively than the male target, this main effect was qualified by an interaction with scenario type. As predicted, the results provide support for Hypothesis 4, and are consistent with previous work suggesting that reactions towards counter-stereotypic men are mainly negative and that reactions towards chivalrous men are mainly positive (Kilianski and Rudman 1998). The man in the gender counter-stereotypic condition was rated as less appropriate (4a), warm (4b), and competent (4c) than the woman, but the man in the gender stereotypic condition was rated as more appropriate (4a), warm (4b), and competent (4c) than the woman.

Interestingly, when exploring this interaction between condition and target gender by looking at the effects of condition within gender we find that judgments of male competence and warmth are affected by condition, whereas judgments of female competence and warmth are not affected by condition. This pattern of male findings provides additional evidence of the particularly restrictive nature of the masculine role (e.g., Sandnabba and Ahlberg 1999; Wood et al. 2002). Thus, men who do not enact prescribed, agentic behavior in romantic contexts experience backlash effects. This pattern of female findings is also interesting, as relatively little research has explored backlash against counter-stereotypic women in contexts outside of the workplace. Perhaps the pairing of the gender counter-stereotypic behavior with a dating context, a gender stereotypic context, resulted in a mitigation of the typical backlash effects associated with enacting counter-stereotypic behavior. Future research may explore this possibility. Notably, however, judgments of female appropriateness were affected by condition such that the woman in the gender counter-stereotypic condition was rated as less appropriate than the woman in the gender stereotypic or egalitarian conditions.

No participant gender main effects or interactions were obtained in our primary analyses, consistent with previous research suggesting few gender differences in the domain of perceptions of dating behaviors (Bartoli and Clark 2006; Rose and Frieze 1993). These results are also consistent with the general psychology of gender literature findings that there are more gender differences in stimuli effects (people rating male and female targets differently) than there are in terms of subject effects (men and women behaving differently) (e.g., Matlin 2012).

Perceptions of Egalitarian Dates

Although a priori hypotheses were not made regarding reactions to the egalitarian dating scenario, providing insight into individuals’ perceptions of egalitarian dates is an important contribution of the current work. Previous research has explored the egalitarian nature of dating script content, but little work has explored reactions to egalitarian dates. Despite the fact that dating scripts remain gendered in nature, participants perceived the egalitarian dating scenario as the most typical. Perhaps these perceptions of the typicality of egalitarian dates are influenced by the knowledge that people are now likely to endorse egalitarian beliefs. Indeed, people may believe there has been more progress towards gender equity in dating behaviors than there actually has been (Eaton and Rose 2011). Other factors may also contribute to the typicality of egalitarian dates in college settings. For example, monetary concerns among college students may increase the typicality of heterosexual dates in which both the man and woman contribute funds.

The current results also suggest that reactions to egalitarian dates are relatively positive, although not as positive as reactions to gender stereotypic dates. Targets in the egalitarian dating condition were rated as more appropriate, warm, and competent than those in the gender counter-stereotypic condition, but as less appropriate, warm, and competent than those in the gender stereotypic condition. Perceptions of egalitarian dates were unrelated to ambivalent sexism. Thus, although reactions to gender stereotypic dates remain positive, we obtain promising evidence of the acceptance of gender equality, as even those high in ambivalent sexism are accepting of egalitarian dating practices.

Strengths and Limitations

This study makes a number of important contributions. First, very little research has been conducted examining the impact of individual differences on perceptions of dating relationships. Ambivalent sexism in particular was explored because of its impact on other aspects of relationship functioning (Chen et al. 2009; Glick and Fiske 2002). Thus, this research ties the dating script literature into the broader gender literature related to ambivalent sexism by providing evidence that ambivalent sexism moderates reactions to dating behaviors. Our findings suggest that although dating scripts remain gendered, a greater appreciation for gender equality in dating exists among individuals low in ambivalent sexism. Second, although individuals today are highly likely to endorse egalitarian roles in relationships, very little research has addressed perceptions of these behaviors (Eaton and Rose 2011). The current findings suggest that whereas reactions to counter-stereotypic dates remain relatively negative, particularly for those individuals high in ambivalent sexism, reactions to egalitarian dates are more positive, even for those high in ambivalent sexism. These perceptions of dating behaviors are especially important to investigate, as they can perpetuate gender stereotypes and differences by affecting individuals’ own dating experiences (Rose and Frieze 1993), perceptions of expected subsequent behavior (Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010), and can serve as the basis for establishing gender power differentials in developing relationships. Finally, the current work expands research on backlash by demonstrating that men may be particularly likely to experience backlash effects in social, romantic contexts when they do not enact prescribed agentic behaviors. Women did not experience backlash effects for enacting unexpected agentic behaviors, suggesting that social, romantic contexts may mitigate backlash effects for women.

Future research may address some of the limitations of the current work. The current work employed self-report methods, which can be subject to social desirability effects. Future research may employ methods that minimize social desirability concerns, such as implicit measures. The current work also had a modest sample size. Future research should pay particular attention to sample size to ensure adequate power to detect effects. In addition, in the current work, ambivalent sexism was measured after the scenarios, which raises the possibility that the scenarios influenced participants’ ambivalent sexism responses. In response to this concern, we reanalyzed our data using condition to predict ambivalent sexism and did not obtain significant effects. This finding suggests that ambivalent sexist views are relatively stable. However, future research would benefit from counterbalancing the presentation of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory such that participants are randomly assigned to complete these measures at either the beginning or the end of the study.

The current work documents trends towards the acceptance of gender equity in dating in that there is a greater appreciation for gender equality among certain people (those low in ambivalent sexism) and in certain circumstances (egalitarian as opposed to gender counter-stereotypic dates). The current work also suggests that trends towards the appreciation of gender equity have been made when put into the context of previous research in the area (e.g., Eaton and Rose 2011). However, future work may directly explore progress towards gender equality in reactions to different types of dating behaviors over time by using longitudinal designs. Additionally, previous research suggests that dating behaviors have important implications for individuals’ perceptions of appropriate subsequent behavior. In particular, dating behaviors have been related to sexual expectations and rape myth acceptance (Bostwick and DeLucia 1992; Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). Thus, future work may further explore the role of ambivalent sexism in sexual expectations following more egalitarian dates.

Future research may also explore the role of ambivalent sexism towards men in our obtained effects (Glick and Fiske 1999). Ambivalent attitudes towards men and women are highly correlated, but we would expect ambivalent attitudes towards men to more strongly predict negative reactions towards counter-stereotypic males. Notably, no interactions between ambivalent sexism and target gender were obtained in this research. Thus, in this study ambivalent sexism predicts reactions to female and male targets equally. This provides further evidence for treating ambivalent sexism generally as an index of endorsement of traditional gender roles.

Finally, future research may explore these issues across different cultures. As mentioned earlier, we focus specifically on perceptions of dating behaviors in a U.S. sample, as cultures vary in terms of their gendered expectations and relationship behaviors. For example, Eaton and Rose (2012) find that U.S. Hispanic adults have particularly gendered dating scripts. Additionally, research on Indian (Dasgupta 1998) and Chinese (Luo 2008) U.S. immigrants suggests that dating can be an arena in which cultural differences manifest and issues of different values and expectations play out. Although there may be mean differences in ambivalent sexism across cultures, previous theory and research also suggest that ambivalent sexism generally operates similarly across cultures (Chen et al. 2009, Glick et al. 2000). Thus, despite differences in normative dating behavior across cultures, future research may explore whether ambivalent sexism also moderates reactions to different types of dates across cultures.

Conclusions

Overall, gender stereotypic dates were evaluated most positively, which may contribute to the perpetuation of traditional dating scripts. This finding is consistent with previous work suggesting that less progress towards gender equality in dating behaviors has been made than one might expect given recent increases in egalitarianism (Eaton and Rose 2011). We also obtain evidence of the restrictive nature of the male gender role, as men were rated less favorably in the counter-stereotypic date than were women. In fact, warmth and competence ratings were only affected by date type for male targets. Thus, men can experience backlash when they fail to enact expected agentic behaviors in romantic contexts.

Importantly, the data also suggest that perceptions of dating experiences depend on ambivalent sexism. Consistent with predictions, those high in ambivalent sexism had more negative reactions to gender counter-stereotypic dating scenarios than those low in ambivalent sexism. However, ambivalent sexism did not predict different reactions towards egalitarian dating scenarios, and egalitarian dates were rated as most typical regardless of participants’ ambivalent sexism. Thus, the current work obtains promising evidence of the appreciation of gender equality in dating in the United States, as even those high in ambivalent sexism are accepting of egalitarian dating practices.

References

Appel, M., & Mara, M. (2013). The persuasive influence of a fictional character’s trustworthiness. Journal of Communication, 63, 912–932. doi:10.1111/jcom.12053.

Abelson, R. P. (1981). Psychological status of the script concept. American Psychologist, 36, 715–729. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.36.7.715.

Alksnis, C., Desmarais, S., & Wood, E. (1996). Gender differences in scripts for different types of dates. Sex Roles, 34, 321–336. doi:10.1007/BF01547805.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642. doi:10.1002/ejsp.270.

Bartoli, A. M., & Clark, M. D. (2006). The dating game: Similarities and differences in dating scripts among college students. Sexuality and Culture, 10, 54–80. doi:10.1007/s12119-006-1026-0.

Bohner, G., Ahlborn, K., & Steiner, R. (2010). How sexy are sexist men? Women’s perception of male response profiles in the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory. Sex Roles, 62, 568–582. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9665-x.

Bostwick, T. D., & DeLucia, J. L. (1992). Effects of gender and specific dating behaviors on perceptions of sex willingness and date rape. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 11, 14–25. doi:10.1521/jscp.1992.11.1.14.

Brescoll, V. L., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychological Science, 19, 268–275. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x.

Chaing, J. J., Saphire-Bernstein, S., Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Taylor, S. E. (2012). Cultural differences in the link between supportive relationships and proinflammatory cytokines. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 511–520. doi:10.1177/1948550612467831.

Chen, Z., Fiske, S. T., & Lee, T. L. (2009). Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage. Sex Roles, 60, 765–778. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9585-9.

Dasgupta, S. D. (1998). Gender roles and cultural continuity in the Asian Indian immigrant community in the U.S. Sex Roles, 38, 953–974. doi:10.1023/A:1018822525427.

Eaton, A. A., & Rose, S. M. (2011). Has dating become more egalitarian? A 35 year review using Sex Roles. Sex Roles, 64, 843–865. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9957-9.

Eaton, A., & Rose, S. M. (2012). Scripts for actual first data and hanging-out encounters among young heterosexual Hispanic adults. Sex Roles, 67, 285–299. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0190-y.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Emmers-Sommer, T. M., Farrell, J., Gentry, A., Stevens, S., Eckstein, J., Battocletti, J., & Gardener, C. (2010). First date sexual expectations: The effects of who asked, who paid, date location, and gender. Communication Studies, 61, 339–355. doi:10.1080/10510971003752676.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2006). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00379.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118. doi:10.1037//O003-066X.56.2.1O9.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2002). Ambivalent sexism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 115–188. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80005-8.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334. doi:10.1177/01461672972312009.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., ... López, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763.

Green, S. K., & Sandos, P. (1983). Perceptions of male and female initiators of relationships. Sex Roles, 9, 849–852. doi:10.1007/BF00289958.

Kilianski, S. E., & Rudman, L. A. (1998). Wanting it both ways: Do women approve of benevolent sexism? Sex Roles, 39, 333–352. doi:10.1023/A:1018814924402.

Laner, M. R., & Ventrone, N. A. (2000). Dating scripts revisited. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 488–500. doi:10.1177/019251300021004004.

Lee, T. L., Fiske, S. T., Glick, P., & Chen, Z. (2010). Ambivalent sexism in close relationships: (Hostile) power and (benevolent) romance shape relationship ideals. Sex Roles, 62, 583–601. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x.

Levinger, G. (1983). Development and change. In H. H. Kelley, E. Berscheid, A. Christensen, J. H. Harvey, T. L. Hustoson, G. Levinger, … D. R. Peterson (Eds.), Close relationships (pp. 315–359). San Francisco: Freeman.

Luo, B. (2008). Striving for comfort: “Positive” construction of dating cultures among second-generation Chinese American youths. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 867–888. doi:10.1177/0265407508096699.

Matlin, M. W. (2012). The psychology of women. Belmont: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Moor Serewicz, M. C., & Gale, E. (2008). First-date scripts: Gender roles, context and relationship. Sex Roles, 58, 149–164. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9283-4.

Morgan, E. M., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2007). Wanting sex and wanting to wait: Young adults’ accounts of sexual messages from first significant dating partners. Feminism & Psychology, 17, 515–541. doi:10.1177/0959353507083102.

Overall, N. C., Sibley, C. G., & Tan, R. (2011). The costs and benefits of sexism: Resistance to influence during relationship conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 271–290. doi:10.1037/a0022727.

Roets, A., van Hiel, A., & Dhont, K. (2012). Is sexism a gender issue? A motivated social cognition perspective on men’s and women’s sexist attitudes toward own and other gender. European Journal of Personality, 26, 350–359. doi:10.1002/per.843.

Rose, S., & Frieze, I. H. (1993). Young singles’ contemporary dating scripts. Sex Roles, 28, 499–509. doi:10.1007/BF00289677.

Ross, L. E., & Davis, A. C. (1996). Black-White college student attitudes and expectations in paying for dates. Sex Roles, 35, 43–56. doi:10.1007/BF01548174.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629–645. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629.

Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 157–176. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.157.

Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, K. (2007). The F word: Is feminism incompatible with beauty and romance? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 125–136. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00346.x.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2008). The social psychology of gender. New York: The Guilford Press.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 743–762. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00239.

Sandnabba, N. K., & Ahlberg, C. (1999). Parents’ attitudes and expectations about children’s cross-gender behavior. Sex Roles, 40, 249–263. doi:10.1023/A:1018851005631.

Sibley, C. G., & Overall, N. C. (2011). A dual process motivational model of ambivalent sexism and gender differences in romantic partner preferences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 303–317. doi:10.1177/0361684311401838.

Travaglia, L. K., Overall, N. C., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). Benevolent and hostile sexism and preferences for romantic partners. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 599–604. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.015.

Wesselmann, E. D., & Kelly, J. R. (2010). Cat-calls and culpability: Investigating the frequency and functions of stranger harassment. Sex Roles, 63, 451–462. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9830-2.

Wood, E., Desmarais, S., & Gugula, S. (2002). The impact of parenting experience on gender stereotyped toy play of children. Sex Roles, 47, 39–49. doi:10.1023/A:1020679619728.

Viki, G. T., Abrams, D., & Hutchison, P. (2003). The “true” romantic: Benevolent sexism and paternalistic chivalry. Sex Roles, 49, 533–537. doi:10.1023/A:1025888824749.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and several anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Gender Stereotypic Vignette

On a Friday night, Brian picks Karen up for their date. He pulls up in front of her apartment in his car. He gets out of the car to open the passenger door for her. Then they drive to a nice restaurant they’ve been looking forward to trying. They talk about their days during the drive. When they arrive, the hostess brings them to their table. Brian pulls out Karen’s chair and lets her sit first. They look at the menu and talk about weekend plans. Shortly after, the server comes over to get their order. Brian orders for Karen first and then orders for himself. Karen and Brian enjoy dinner and have a nice conversation. When the server comes with the check, Brian reaches for his wallet and pays for both of them. They get up to leave the restaurant. As they exit the restaurant, Brian steps in front of Karen to pull open the door for her, letting her walk through first. They chat about how great the food was. On the way to the car, the wind starts blowing some, and Brian offers Karen his jacket so she doesn’t get too cold. They get into the car to drive back home.

Egalitarian Vignette

On a Friday night, Brian and Karen meet up for their date. They get into a car. Then they drive to a nice restaurant they’ve been looking forward to trying. They talk about their days during the drive. When they arrive, the hostess brings them to their table. They each pull out their chair and sit down. They look at the menu and talk about weekend plans. Shortly after, the server comes over to get their order. Brian and Karen each order. They enjoy dinner and have a nice conversation. When the server comes with the check, they reach for their wallets and pay for their meals. They get up to leave the restaurant. As they exit the restaurant, they walk together. They chat about how great the food was. On the way to the car, the wind starts blowing some, so they put on their jackets so they don’t get too cold. They get into the car to drive back home.

Gender Counter-Stereotypic Vignette

On Friday night, Karen picks Brian up for their date. She pulls up in front of his apartment in her car. She gets out of the car to open the passenger door for him. Then they drive to a nice restaurant they’ve been looking forward to trying. They talk about their days during the drive. When they arrive, the hostess brings them to their table. They each pull out their chair and sit down. They look at the menu and talk about weekend plans. Shortly after, the server comes over to get their order. Karen orders for Brian first and then orders for herself. They enjoy dinner and have a nice conversation. When the server comes with the check, Karen reaches for her wallet and pays for both of them. They get up to leave the restaurant. As they exit the restaurant, Karen steps in front of Brian to pull open the door for him, letting him walk through first. They chat about how great the food was. On the way to the car, the wind starts blowing some, so they put on their jackets so they don’t get too cold. They get into the car to drive back home.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCarty, M.K., Kelly, J.R. Perceptions of Dating Behavior: The Role of Ambivalent Sexism. Sex Roles 72, 237–251 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0460-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0460-6