Abstract

The current study expands upon body image research to examine how gender, self-esteem, social support, teasing, and family, friend, and media pressures relate to body image and eating-related attitudes and behaviors among male and female adolescents (N = 177). Results indicated that adolescents were dissatisfied with their current bodies: males were concerned with increasing their upper body, whereas females wanted to decrease the overall size of their body. Low self-esteem and social support, weight-related teasing, and greater pressures to lose weight were associated with adolescents’ negative body esteem, body image, and eating attitudes. Females displayed more high risk eating behaviors—which were associated with more psychosocial risk factors—than males, whose high risk attitudes and behaviors were only associated with low parental support and greater pressure to be muscular. Reducing adolescents’ perceptions of appearance-related pressure from family and friends may be key for enhancing body image and decreasing links between low self-esteem and negative eating behaviors and weight-related perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

During a time of substantive social, physiological, and cognitive change, many adolescents become acutely attuned to their weight and body. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey results for 2005, 45.6% of high school students were trying to lose weight. Although the desire to do so was more prevalent among females (61.7%), males also reported trying to lose weight (29.9%) (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006). Both male and female adolescents face numerous changes associated with puberty and are more attentive to changes in their bodies during this developmental period. Previous research on body image and eating disorders has focused primarily on female adolescents and less so on males (Grabe and Hyde, 2006) as such issues were solely associated with women. In reality, however, body and weight-related issues are much less selective. While males may be less concerned with losing weight or decreasing the size of their body, they are more likely to want to gain muscle (McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003; Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2003; Smolak et al., 2005; Weltzin et al., 2005; Wiseman et al., 2004). Not surprisingly, the pressure to increase one’s muscles has been linked to body image among males (Carlson Jones, 2004). The current study contributes to the growing research on body image and eating behaviors by adding to our knowledge about how families and friends influence adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors beyond just support and teasing to include both pressures to be thin and to gain muscle. In addition, the current research expands our knowledge about adolescents’ perceptions of their bodies to include upper body perceptions and muscularity in addition to whole body weight perceptions, which may help us to understand better how males see themselves. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the current research focuses on how the risk factors for problematic eating attitudes and behaviors may differ for male and female adolescents. A broader understanding of the factors that contribute to poor body image among males and females may facilitate earlier detection and, thus, quicker treatment of eating and body-related issues among adolescents.

Research has clearly linked adolescents’ body image, specifically body dissatisfaction, with the prevalence of eating disorders and dieting (Griffiths and McCabe, 2000; McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003; Phares et al., 2004; Wiseman et al., 2004). Body image relates to how adolescents feel about and perceive their changing bodies and is affected by physiology, psychological factors, and society (Rierdan and Koff, 1997). Negative body image or body image disturbance has been measured by examining cognitive components such as negative attitudes about the body or unrealistic expectations for appearance; behavioral components such as avoiding perceived body scrutiny from others (e.g., avoiding swimming); and perceptual components where body size perceptions are evaluated (Thompson et al., 1999b). Adolescents’ body image can be influenced by factors such as gender, self-esteem, messages from the media, and support and pressure from family and friends. The patterning of beliefs, behaviors, and perceptions is likely to be different for males and females.

The onset of puberty and numerous social context changes during early adolescence may set the stage for increased awareness among male and female adolescents of body image and concerns about weight and muscularity. In general, early adolescent girls are more likely to diet and are more likely to have negative feelings about their bodies, while early adolescent boys are more likely to focus their concerns on muscularity and have more positive feelings about their bodies (CDC, 2006; Harter, 1999; Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2003; Weltzin et al., 2005; Wiseman et al., 2004). Similar to the female desire to be thin, the male desire to increase the strength and size of their muscles is consistent with the culturally defined, stereotypic images of males portrayed in the media (Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2003). The focus on males and body image, however, is a fairly recent phenomenon, as eating disorders and poor body image have commonly been thought of and referred to as women’s illnesses (Pope et al., 2000). Pope and colleagues (2000) refer to the secret crisis of male body dissatisfaction in their book, The Adonis Complex. Males who suffer from muscle dysmorphia—a reverse anorexia nervosa—look in the mirror and see puny and frail men, no matter how strong and muscular they may actually be (Pope et al., 2000). Both male and female adolescents’ attitudes about their bodies are associated with a number of different individual, family, peer, and media influences.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem is so intrinsically linked to thoughts about one’s body that physical appearance has consistently been found to be the number one predictor of self-esteem at many ages (Harter, 1999). Thus, it should come as no surprise that positive body image is linked to higher self-esteem and positive affect, and may serve as a protective factor against mental health issues such as depression (Klaczynski et al., 2004; McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003). Poor body image, on the other hand, is associated with feelings of depression, lower self-esteem, negative affect and, ultimately, eating disorders (McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003; Phares et al., 2004; Stice and Bearman, 2001). The higher prevalence of poor body image among adolescent females may help to explain the fact that they tend to exhibit lower levels of self-esteem than their male counterparts during adolescence (Siegel et al., 1999). The strong links between self-esteem and body image may also be accounted for by other family and friend influences as adolescents’ self-perceptions are often shaped by their perceptions of what others think of them. The current research helps to determine whether the links between self-esteem and negative body image are reduced when accounting for more extensive influences from the media, family, and friends.

Pressures from the media

Media usage is fairly heavy among youth; they may often turn to the media to help them deal with issues associated with their changing bodies and identities. In various forms, the mass media transmit messages to adolescents regarding the desirability and undesirability of physical attributes (Ricciardelli et al., 2000). Female adolescents in particular seek out magazines, internalize the messages presented, and use the media as a source of information about how to improve their physical appearance (Littleton and Ollendick, 2003). In early adolescence, girls who look to magazines and advertising as important modes of defining and attaining the ideal body are more likely to experience body dissatisfaction due to the obvious discrepancy between their actual body size and the ideal depicted in the media (Levine and Smolak, 2002). According to a survey of adolescent girls (Field et al., 2001), 69% reported that images of females displayed in magazines influence their perceptions of the ideal body figure, and 47% reported that the images evoked in them a desire to diet and lose weight. In addition, simply watching television has been associated with an increased desire among preadolescent girls to have a thin body when they mature, and also with increased disordered eating over time (Harrison and Hefner, 2006).

For males, pressures from the media tend to be in the opposite direction—associated with muscularity as opposed to thinness. Thus, while females are primarily focused on losing weight, adolescent males tend to adopt strategies such as exercise or the use of food supplements in an attempt to achieve the muscular, V-shaped sociocultural ideal body (McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003). Although males who reported attempting to look like same-sex figures in the media were more likely to become concerned with weight and diet (Field et al., 2001), cross-sectional studies suggest that males, compared to females, perceive fewer pressures from the media to conform to the cultural ideal (McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2001). In one study, half of the males reported that the media had no effect on their body image or eating behaviors (Ricciardelli et al., 2000).

Influences of friends and family

Most adolescents are exposed to mass media; however, not all adolescents who deviate from the cultural appearance ideals develop body-related concerns. Thus, other factors are likely to contribute to adolescents’ increased vulnerability. It may be that messages communicated by the media only become problematic when they are reinforced by more immediate sociocultural agents such as parents and peers (Dunkley et al., 2001). Although parents and friends may provide social support, they may also increase adolescents’ body image concerns through teasing or increasing pressures youth feel to change their appearance.

Social support

Relationships with parents that are more conflict-ridden and less warm and supportive are predictive of increased dieting and lower body image concurrently and longitudinally (Archibald et al., 1999). Girls with eating disorders report feeling more criticized, less accepted, and less close to their parents than controls (Swarr and Richards, 1996). Conflict and lack of closeness within the mother-daughter relationship, in particular, relate to increases in female adolescents’ weight concerns from age eleven to eighteen (May et al., 2006). The link between mother-son relationships and weight concerns is less prevalent in the research literature. Previous research suggests that only conflict within the father-adolescent relationship is predictive of weight concerns across the course of adolescence in both males and females (May et al., 2006). In contrast, emotional support from family—particularly in the form of positive feedback and encouragement—may serve to buffer some of the more negative sociocultural influences, and help adolescents develop and maintain a positive body image over time (Bearman et al., 2006; Ricciardelli et al., 2000; Stice and Whitenton, 2002). Longitudinal results suggest that females who have healthy relationships with both their mothers and fathers report fewer weight and eating concerns both initially and two years later (Swarr and Richards, 1996).

During adolescence, both males and females become more peer-oriented as reliance on friends for support and approval increases significantly. Lower peer acceptance, perceived social support, and friendship intimacy have been found to predict poor body image in adolescent females (Gerner and Wilson, 2005). Results from a 2-year prospective investigation (Stice et al., 2002) suggest that support from peers may play a larger role in predicting negative eating-related behaviors than parental support. In terms of binge eating, in particular, low perceived support from peers was found to be predictive of onset in female adolescents, while support from parents was not (Stice et al., 2002). On the other hand, a significant number of studies focusing solely on adolescent males have failed to find evidence for the relationship between parent and peer relations and negative eating-related attitudes and behaviors (Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2004).

Previous research suggests that friends’ social support and acceptance may help adolescents rise above sociocultural pressures and feel more positively about their bodies by fostering resilience (Stice et al., 2002). However, the compensatory effects of friends’ social support on adolescents’ feelings about their bodies and eating behaviors may not adequately offset other detrimental influences such as teasing or the pressures that adolescents’ perceive because of their friends’ attitudes or behaviors. Friends’ body image concerns and eating behaviors predict adolescents’ own concerns and behaviors (Paxton et al., 1999). While friends who encourage dieting and other more extreme weight loss strategies such as purging or starvation may have adverse effects on body image, friends who are less appearance and weight-oriented may provide a protective environment for otherwise high-risk females (Paxton, 1996).

Teasing

Appearance-related teasing and criticism by family and friends increase adolescents’ feelings of body dissatisfaction by reinforcing the societal value of appearance and emphasizing desirable physical attributes (Jones et al., 2004). A number of studies (e.g., Cash, 1995) suggest that it is not teasing—in and of itself—that influences body image. Rather, it is the frequency, longevity, and emotional impact of the teasing that is related to adolescents’ feelings about their bodies. Research focusing on the particular effects of teasing on female adolescents found that those who are teased about their weight, body shape, and appearance tend to exhibit poorer body image and are more likely to diet (Lieberman et al., 2001). They are also at risk for higher levels of social comparison, internalization of the sociocultural ideal of thinness, restrictive and bulimic eating behaviors, depression, and lower levels of self-esteem (Keery et al., 2005). In a retrospective study of college women, approximately three-quarters of the women reported they were teased repeatedly and/or criticized about their appearance during adolescence; they found this teasing upsetting and many thought that it had a negative impact on their body image development (Rieves and Cash, 1996).

Although peers may be most often cited as teasers, members of the family—more likely siblings than parents—are often seen as culprits as well (Rieves and Cash, 1996). Paternal teasing can have both direct and indirect effects through siblings on adolescents, as modeling of teasing behavior by fathers is associated with higher levels of sibling teasing (Keery et al., 2005). Males and females do not differ in their reports of appearance-related feedback from their mothers (Schwartz et al., 1999), or in their perceived frequency of parental teasing in general (Phares et al., 2004). Females, however, receive significantly more negative feedback from their fathers (Schwartz et al., 1999). Longitudinal studies show that women who were teased about their weight in childhood were more dissatisfied with their appearance during adulthood (Lieberman et al., 2001).

The links between teasing and body dissatisfaction and emotional well-being exist among males as well. In a longitudinal study of middle school and high school students, approximately one third of the males and just under half of females reported weight-related teasing at the start of the study, which was associated with lower self-esteem and body dissatisfaction five years later (Eisenberg et al., 2006). Male adolescents perceive appearance-related pressure and teasing at levels that are similar to or higher than females (Jones and Crawford, 2006), and appearance-related criticism by peers is significantly positively correlated with body dissatisfaction among males (Jones et al., 2004).

Pressure

Pressures from friends and family to conform to the stereotypical ideal can either be direct (i.e., teasing or criticism about weight) or indirect (i.e., a friend voicing concern about the size of her own body), and may differ in the degree to which they exert influence (Stice et al., 2003). In one longitudinal study of female adolescents, initial deficits in social support and pressures to be thin from family, friends, and the media—but not weight-related teasing—were associated with increased body dissatisfaction over time (Stice and Whitenton, 2002). These results suggest that pressure-exerting messages about the importance of being thin may have more adverse effects on adolescent body satisfaction than weight-related teasing. The effects of pressures to be thin from parents and peers on eating behaviors are important even after accounting for adolescents’ self-esteem (Stice et al., 2002).

Pressures from peers to be thin or muscular are particularly powerful during adolescence as females and males are likely to talk to their friends about dieting or muscle-building (Jones and Crawford, 2006; Phares et al., 2004; Tiggemann, 2001). Not surprisingly, adolescents who make social comparisons and whose relationships and conversations tend to be based on dieting and appearance are more likely to exhibit body dissatisfaction (Carlson Jones, 2004; Jones et al., 2004). Research suggests that perceived pressure from peers to be thin is more associated with increases in adolescents’ body dissatisfaction over time than pressures to be thin from family or the media (Presnell et al., 2004). It is important to note that the pressure exerted from peers may be quite subtle and still have significant effects. In one study, undergraduate female students were randomly assigned to a control condition or one in which an ultra-thin confederate voiced complaints about how fat she felt and her intentions to lose weight (Stice et al., 2003). Even though the manipulation was considered by the researchers to be minor, the group of females who were exposed to peer pressure to be thin showed significant increases in body dissatisfaction whereas the control group did not. In another study, when female adolescents were asked to evaluate their current figure and the ideal figures they perceived from the media, family and friends, their current figure was larger than all ideals, with peers exerting the strongest perceived pressure to be thin and parents the least (Dunkley et al., 2001). Although the majority of the studies discussed focus on females, perceived pressure from friends and family to lose weight is also an important factor is predicting disordered eating and body dissatisfaction in adolescent males, as evidenced by cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2004).

In contrast, some research suggests that parental pressures, as opposed to peer pressures, are more associated with weight concerns among adolescents (Field et al., 2001). Field and her colleagues (2001) found that females who reported that it was important to their parents that they were thin were twice as likely as their peers to become concerned with weight. In addition, when males and females reported that their weight was important to their father, in particular, they were more likely to diet. These effects were salient even after controlling for age and BMI, and they found no negative effects of pressure from peers on eating behaviors or attitudes.

Fewer studies have been conducted on the pressure to gain muscle exerted on adolescents by family and friends, and most of the research has focused on boys. As is not the case with females, the majority of body-related messages received by males are in the form of praise or compliments, particularly from mothers and female friends (Ricciardelli et al., 2000). Among males, less positive messages from mothers to lose weight have been associated with eating less to lose weight, while messages from fathers to exercise more have been associated with exercising to change body shape or gain muscle (Ricciardelli et al., 2000). Cross-sectional studies, however, suggest that perceived pressure from parents and peers to gain muscle is only weakly associated with weight and muscle gain strategies in both male and female adolescents (Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2004).

Current research and hypotheses

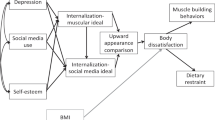

The current research focuses on how self-esteem, perceptions of pressure and support from family and friends, weight-related teasing, and media pressure are associated with adolescents’ perceptions of their bodies and their eating behaviors. Specifically, we examined a multivariate model using self-esteem, and perceived pressure from friends, family, and the media as predictors of adolescents’ negative eating attitudes and behaviors, discrepancies between their ideal and actual body perceptions, and their body esteem. Given that the emphasis on body perceptions is more focused on muscles for males and weight for females (Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2003), we also examined gender differences in both the predictor variables and body image indicators. Lastly, we examined how adolescents most at risk for eating disorders (those with the most negative eating attitudes and behaviors) differed from those less at risk.

We examined the following hypotheses:

-

A.

In general, females are expected to report more negative eating attitudes and behaviors and lower body esteem than their male counterparts. They are also expected to exhibit lower levels of global self-esteem.

-

B.

In terms of perceived pressures, males are expected to perceive more pressure from friends and family to gain muscle, and report greater discrepancies between their perceived actual and ideal upper body figures compared to females. Females, in contrast, are expected to perceive more pressure from friends and family to lose weight, and report greater discrepancies between their perceived actual and ideal overall bodies.

-

C.

In relation to the body image and eating behavior outcomes, we expect perceived pressures from friends and family members to differ in their effects from low support and teasing. We further expect these pressures to be associated with negative eating behaviors and weight-related attitudes for both males and females, even after controlling for self-esteem, social support, and teasing from family and peers. Accounting for pressures is expected to help explain the effects of these factors, particularly self-esteem, on the outcomes.

-

D.

We expect that the factors associated with high-risk negative eating attitudes and behaviors will differ between males and females.

Method

Sample and procedures

Participants (N = 177) included eighth through twelfth grade students, aged 13 to 19 (M = 15.8), from three schools in the Northeast United States. One of the schools was public and two of the schools were parochial (one co-ed and one same-sex). The sample was 56.5% female and 92.7% Caucasian.

Superintendents of public and parochial schools were supplied with a brief description of the study, a copy of the questionnaire, and copies of the consent forms and letter that were to be sent home with students. Interested schools contacted the researchers with the names of particular teachers who desired to be of assistance. Paper and pencil surveys were administered during school hours to adolescents who returned both assent and parental consent forms. The questionnaire was self-administered and trained undergraduate students remained in the classroom to facilitate administration and answer any questions.

Measures

The measures in the questionnaire were all adolescent self-report; see Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Eating attitudes and behaviors

The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) (Garner and Garfinkel, 1979) was used to measure negative eating attitudes and behaviors. The EAT-26 consists of 26 statements referring to anorexic/bulimic-like eating attitudes (e.g., “I am preoccupied with the thought of having fat on my body”), and behaviors (e.g., “I cut my food into small pieces”). Participants were asked to indicate frequency of each attitude or behavior on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from always (1) to never (6). In terms of scoring, three points were allotted to always, 2 points to usually, 1 point to often and 0 points to sometimes, rarely, and never. A total score greater or equal to 20 points is indicative of an eating problem (Garner and Garfinkel, 1979). The EAT has high criterion validity in discriminating between those with and without eating disorders for males and females and it is highly negatively correlated with Body Mass Index (Gila et al., 2005; Mintz and O’Halloran, 2000). The EAT-26 has been used extensively with both early adolescents (e.g., Gila et al., 2005; Pendley and Bates, 1996) and with high school samples (e.g., Gila et al., 2005; Rosen et al., 1988), and it has shown good construct validity when validated against other eating behavior measures (Rosen et al., 1988). The means and standard deviations on the EAT-26 for girls and boys in the current sample (see Table 1) are similar to norms for other adolescent samples (Rosen et al., 1988).

Body image and body esteem

The Contour Drawing Rating Scale (CDRS) (Thompson and Gray, 1995) for adults was used as a measure of body image, indicating discrepancies between adolescents’ actual and ideal body figures. The scale consists of 9 female and 9 male contour drawings that increase in size/weight from severely underweight (1) to very overweight (9). Body image was determined by measuring the discrepancy between the numbers associated with their actual and ideal figures. The CDRS has been used with early adolescent and high school samples (e.g., Lombardo et al., 2004; Wertheim et al., 2004) and shown good test-retest reliability and construct validity (Wertheim et al., 2004).

The Breast/Chest Rating Scale (BCRS) (Thompson and Tantleff, 1992), which consists of 5 female and 5 male figures, was also used as a measure of body image. Unlike those featured in the CDRS, the figures in the BCRS corresponded to the upper body only. The female figures ranged from small-chested (1) to a figure with large breasts (5). The male figures increased in muscularity from no visibly muscles (1) to well-defined pectorals and abs (5). The BCRS has been used primarily with college students (e.g., Thompson and Tantleff, 1992). Reviews of the literature on male body image, however, have suggested more extensive use of chest and body image rating scales with adolescents because younger rather than older males are likely to desire a more muscular appearance (Cafri and Thompson, 2004).

An abbreviated version of the Body-Esteem Scale (BES) (Franzoi and Shields, 1984) was used to measure body esteem. The scale consists of 16 body parts (e.g., waist, thighs, hips) and 5 related functions (e.g., appetite, muscular strength, health). Participants indicated how they felt about each particular part or function on their body. Possible responses ranged from have strong negative feelings (1) to have strong positive feelings (5). Items from the BES have been used with other adolescent samples and have good test-retest reliability and predictive validity (Presnell et al., 2004). The BES has also shown good convergent and discriminant validity (Franzoi, 1994).

Self-esteem

An adapted version of Harter’s (1982) global self-worth scale was used to measure self-esteem. Adolescents reported how much they wished they were different or could change things about themselves and how sure they are of themselves (3 items). Responses ranged from almost never (1) to almost always (5) (Eccles, 1993). This measure has been used on other adolescent samples (Ludden and Eccles, in press) and has acceptable psychometric properties (Harter, 1982).

Parental and peer social support

Adolescents reported the amount of social and emotional support received from parents (e.g., “my parents enjoy hearing what I think”) (4 items) and from friends (e.g., “my friends are good at helping me solve problems”) (3 items) separately [adapted from Procidano and Heller (1983)]. Responses ranged from not true (1) to very true (5). This adapted measure has been used with other adolescent samples (e.g., Bryant and Zimmerman, 2002) and has shown convergent and discriminant validity (Gavazzi, 1994; Procidano and Heller, 1983).

Sociocultural pressures

The Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale (Stice and Bearman, 2001) was used to measure sociocultural pressures. The first 8 statements focus on pressure to be thin and/or lose weight as exerted by friends, family, and the media (e.g., “I’ve noticed a strong message from the media to have a thin body”), while the last 2 relate to teasing about weight or body shape (e.g., “Family members tease me about my weight or body shape”). Eight statements where the words “lose weight” and “thin body” were replaced with “gain muscle” and “muscular body” were added to the original scale. Statements are rated on a 5-point scale from none (1) to a lot (5). The original measures have been used with adolescents and shown good test-retest reliability and predictive validity (Presnell et al., 2004; Stice and Bearman, 2001).

Data analytic approach

First, t-tests were used to examine gender differences on all of the independent and dependent measures. Second, a series of hierarchical step-wise linear regressions were performed where demographics and self-esteem (Model 1); emotional support and weight-related teasing from family and friends (Model 2); and pressure from family, friends, and the media (Model 3) were entered in separate steps to explain variance in the body image and eating attitudes measures (i.e., EAT, BES, CDRS, and BCRS). Third, high risk male and female adolescents were identified on the basis of EAT scores and compared to lower risk adolescents in terms of the independent measures as well as the other dependent measures.

Results

Gender differences

Eating and body image measures

Independent samples t-tests indicated significant gender differences on all measures of eating attitudes, body image and esteem (see Table 1). Females scored significantly higher than males on the EAT-26 (and exhibited a much greater variance in scores) and lower than males on the Body-Esteem Scale, which indicated more negative feelings toward specific body parts and functions. In terms of the whole-body rating scale, males had very little discrepancy between ideal and actual body (the mean was close to zero), whereas the discrepancy between the actual and ideal figures for females was significantly larger, indicating their desire to be smaller than they actually are. Both males and females also seemed to be dissatisfied with their upper bodies. Regardless of gender, a desire to have a larger upper body was expressed. The discrepancy between ideal and actual upper body, however, was significantly larger in males, indicating that they wanted to gain more upper-body weight/muscle. In contrast, the average discrepancy reported by females indicated that they had much less of a desire to gain upper-body weight.

Individual and sociocultural factors

Males and females also differed in terms of individual and sociocultural factors (see Table 1). Females reported higher peer support, teasing from family about weight, pressure from friends and family to lose weight, and media pressure. Males reported higher self-esteem and more pressure from friends and family to gain muscle than females.

Hierarchical regression analyses

Eating attitudes test (EAT-26)

In the first step (Model 1) of the hierarchical linear regression results for the EAT-26 (see Table 2), female adolescents, minority adolescents, and adolescents reporting low self-esteem were more likely to report negative eating attitudes and behaviors. This step explained the largest amount of variance (29%) in the EAT-26 scores, largely due to the strong association between low self-esteem and the EAT-26. Although the next step including support and teasing from family and friends did not explain a significant portion of variance, it did help to explain the links between gender and self-esteem and the EAT, rendering a reduction in these effects. The third and final step, resulting in Model 3, explained a significant portion of variance (8%). Adolescents who reported more pressure from friends and family to lose weight reported more negative eating attitudes and behaviors. Consistent with previous models, minority adolescents and those with low self-esteem also reported higher EAT-26 scores in the final model. Model 3 included a further reduction in the self-esteem effect on EAT-26 scores, indicating that this effect was partly explained by adolescents’ perception of pressure from friends and family to lose weight. The amount of variance (R 2) in adolescents’ negative eating attitudes and behaviors accounted for by the overall model was .40.

Body esteem

Regression results revealed, not surprisingly, in the first step (Model 1) that female adolescents and those who with low self-esteem were more likely to express negative feelings about their body parts and report lower body esteem. This step explained a significant portion of variance (46%) in adolescents’ BES scores; however, the results indicated that the family and friends factors helped to account for this strong association between self-esteem and body esteem. In Model 2, adolescents reporting lower levels of peer support and more teasing from family about weight reported lower body esteem; this was a significant step explaining 5% of the variance in BES scores. In Model 3, the final step added a significant portion of variance (3%). Including the pressures to lose weight factors explained the gender and the teasing effects from the previous models such that they were no longer significant. Results indicated, in this final model, that adolescents perceiving pressure from the media to lose weight reported significantly lower body esteem. As noted from the gender differences above, females tend to report greater pressures from the media than males, which may account for some of the gender differences in body esteem. As expected, self-esteem was associated with body esteem in all of the models. Peer support was also associated with body esteem in the final model. The amount of variance (R 2) in body esteem accounted for by the overall model was .54.

Contour drawing rating scale (CDRS)

The first step (Model 1) for the CDRS (see Table 3), revealed that female adolescents and those with low self-esteem were more likely to report a greater discrepancy between their ideal and actual body figures, indicating that their actual body/figure was larger than their ideal body/figure. Demographics and self-esteem appear to play a significant role in predicting CDRS scores as they explained 28% of the variance within the model. In the second step (Model 2), including the support and teasing factors did not explain a significant portion of the variance; however, it revealed that adolescents who reported having experienced more teasing from family members were more likely to report that their actual body/figure was larger than their ideal body/figure. The third step (Model 3), accounting for pressures from family and friends, was responsible for explaining 18% of the variance. Furthermore, it accounted for a reduction in the effects of gender, self-esteem, and family teasing, such that they were no longer significant. Results from the final model suggest that pressure from friends and family to lose weight may explain why females, those with low self-esteem, and those experiencing teasing from family are more likely to report that they are heavier than their ideal weight. The final model indicated that adolescents reporting less teasing from peers about weight, more pressure from friends and family to lose weight, and less pressure from friends and family to gain muscle were more likely to report that their actual figure was heavier than their ideal figure. The amount of variance (R 2) in CDRS scores accounted for by the overall model was .51.

Breast/chest rating scale (BCRS)

Model 1 revealed significant gender differences in the BCRS in the first step (and in subsequent models), where males were more likely to perceive that their upper bodies were smaller than ideal and females were more likely to indicate that their upper bodies were closer to an ideal build. Note that with the BCRS body image was determined by measuring the discrepancy between actual and ideal figures reported, and that lower scores indicate a desire for larger breasts for females and more muscular upper bodies for males. The means for both males and females were smaller than zero, indicating that, on average, adolescents wanted to increase their upper bodies. The second step, including support and teasing from family and friends, was not a significant step. The final step (Model 3), however, indicated that adolescents reporting pressure from family and friends to lose weight were more likely to want to decrease their upper body size, whereas adolescents who perceive pressure from the media were more likely to want to increase their upper body size. This step marked a significant increase in variance explained (6%) in the BCRS. Unlike the other outcome variables, adolescents’ reports of self-esteem were not associated with the BCRS in any of the models. Overall, this model explained the least variance—R 2 for this model was .24.

High risk EAT scores

In order to examine the characteristics of adolescents most at risk for negative eating attitudes and behaviors, males and females were divided separately into low risk (bottom three quarters of sample) and high-risk (top quartile) groups. For females, an EAT-26 score in the high-risk group was determined to be one of 11 or greater, whereas males in the high-risk group scored 6 or higher (see Table 4 for mean EAT scores and ranges for groups).

Females

Independent samples t-tests indicated that high-risk females as compared to low-risk females reported higher levels of teasing from family, teasing from friends, pressure from friends and family to lose weight, media pressure, and a greater desire to lose weight (higher CDRS discrepancies) (see Table 4). In addition, female adolescents in the high-risk eating attitudes and behaviors group reported less parental support, lower self-esteem, and lower body esteem than adolescents in the low-risk group (see Table 4).

Males

In contrast, only two factors distinguished the high-risk males from the low-risk males in terms of negative eating attitudes and behaviors. Independent samples t-tests revealed that males whose EAT scores fell within the top quartile reported less parental support and more pressure from family and friends to gain muscle than males whose scores fell within the bottom three-quarters of the sample (see Table 4).

Discussion

The current study provides further evidence that body image concerns and negative eating attitudes and behaviors are not limited to female adolescents, and that family influence on these perceptions and behaviors extends beyond support and teasing to include salient pressures to lose weight and gain muscle. Although females reported more negative perceptions regarding eating and their bodies, males also exhibited poor body image and distinguishable risk patterns could be identified. The focus of body-related concerns was different for males and females, consistent with previous research (e.g., McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003). The current study expands upon this research and research by Stice and Bearman (2001) on sociocultural pressures to be thin by identifying pressures that adolescents perceive from family, friends, and the media to gain muscle, which was more prevalent among males. In addition, males were more concerned with increasing the size of their upper body, while females were more concerned with decreasing the overall size of their body. Broadly speaking, females reported more negative self- perceptions and eating attitudes and behaviors. In the current research, females reported significantly higher levels of pressure from friends and family to lose weight, media pressure, and teasing. Males, on the other hand, felt significantly more pressure from friends and family to gain muscle, which has been related to the Adonis complex by Pope and colleagues (2000). The current research also provided evidence that accounting for pressures to lose weight from family, friends, and the media helps to explain why adolescents with low self-esteem are more likely to report negative eating behaviors and weight concerns.

The most salient predictor of negative body image and eating attitudes and behaviors was the family pressure to lose weight reported by adolescents. This factor not only helped to explain why adolescents with low self-esteem may be more vulnerable, it also helped to account for the influence of teasing from family on adolescents’ weight perceptions. Adolescents perceiving these pressures from family and friends to lose weight reported negative eating patterns and perceived that their actual whole and upper bodies differed from their ideal figures. When adolescents perceive these pressures from the people who are closest to them—their family and friends—they may become more distressed, feel more negatively about themselves, diet, and engage in other negative eating behaviors such as bingeing and purging (Ricciardelli et al., 2006; Stice and Bearman, 2001). The current research suggests that some of the reasons why adolescents with low self-esteem are so vulnerable to negative body perceptions are related to the pressures they feel from family and friends to be thin. It may be that adolescents with low self-esteem are more likely to interpret comments from people close to them as inducing pressure and they are more vulnerable to these pressures than adolescents with more self-esteem. The inextricable tie between self-esteem and physical appearance (Harter, 1999) is likely to be affected by and affect how adolescents interpret feedback and interact in their relationships with family members and friends.

These pressures may be particularly damaging when adolescents are emotionally close to their families and friends. The research suggests that peer social support may play a somewhat compensatory role in reducing the negative effects of these pressures on body esteem; however, when the stressors emerge from within this socially supportive relationship, the pressures may not be reduced due to the conflicting perceptions. The effects of social support may not be as strong as one would expect because although adolescents may rely upon their close friends for emotional support, these same friends may help them find ways to obtain what they conceive of as a better body—through dieting or through gaining muscle (Jones and Crawford, 2006; Phares et al., 2004; Tiggemann, 2001). When friendships are characterized by discussing body appearance and ways to enhance appearance, adolescents are more likely to have poor body image themselves (Carlson Jones, 2004; Jones et al., 2004). Interestingly, adolescents who reported that their peers tease them about their weight were more likely to perceive that their body weight was less than ideal, which may suggest some adaptive nature of teasing, or perhaps that the skinniest adolescents are teased.

Further research is needed to examine the nature of family pressures to lose weight. Knowledge about how these pressure messages are conveyed to adolescents—especially in the context of supportive family relationships—may help us alert parents as to how best to promote their adolescents’ health and well-being. Research suggests that the role of the father in teasing and exerting pressure is particularly salient for adolescents (Keery et al., 2005). Although adolescents are considered the optimal source of their own internal experiences (Edelbrook et al., 1985), gathering information from multiple informants (e.g., parents, siblings, teachers, peers) may contribute significantly to our understanding of the social context of adolescents’ perceived pressures regarding appearance. Identifying mismatches between parents (or peers) and adolescents’ perceptions of pressures may reveal how miscommunication and misunderstanding can occur.

In the current research, males and females differed in their mean levels of self-esteem, and perceived parental, peer, and media influences. They also differed in how these factors were associated with high risk eating behaviors and attitudes. This research has helped to unveil how males’ pattern of negative body attitudes are different from females’. Male adolescents in the study reported more pressures from family and friends to gain muscle than females. Interestingly, the mean level of pressure that males report to gain muscle, a moderate level of pressure, is higher than the mean level of pressure that females report to lose weight. This suggests that these pressures are likely to be relevant pressures in boys’ daily lives, and they are worthy of attention. Similarly, males were more likely than females to report that their upper bodies were smaller and less muscular than their ideal figures. Females’ ideal and actual upper body perceptions, on the other hand, were more alike. Although males do not report low body esteem, both the current study and previous research indicate that boys are just as likely to perceive appearance-related pressure as girls (Jones and Crawford, 2006). In this study, pressures to gain muscle, in addition to low parental support, are associated with high risk eating behaviors and attitudes. It is likely that pressures from parents and peers to gain muscle are also associated with additional high risk behaviors not examined here, such as steroid use and exercise dependence, which have been associated with muscularity concerns among boys (Cafri et al., 2005).

Limitations and areas for future research

The results of the current study expand upon the existing research on adolescent body image; however, a number of limitations should be acknowledged. Although we obtained significant results, the sample was small, suggesting that we may have underestimated the effects of some of the predictor variables. Furthermore, it is important to note that two of the schools in which we conducted our research were parochial—one co-ed and one same-sex. While we did not take type of school or religiosity into account, school social and academic context may contribute to adolescents’ beliefs and behaviors regarding health. Previous research suggests that adiposity and socioeconomic status are inversely related and females from private schools have lower BMI’s than those from public schools (Stice and Whitenton, 2002).

Also, the sample was homogeneous in terms of ethnicity. Further research would do well to expand the current research by examining sociocultural pressures regarding thinness and muscularity among diverse ethnic groups as previous research suggests that African American females tend to score higher on measures of body image than their Caucasian counterparts (Archibald et al., 1999; Nishina et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 1999a). Nishina and colleagues (2006), however, suggest more similarities than differences among ethnic groups in terms of adolescents’ perceptions of body image and links to well-being. Research on male adolescents’ desire to gain muscle has primarily failed to include ethnic minority adolescents (e.g., McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003; Smolak et al., 2005). Expanding our study of the pressures from family, friends, and the media associated with gaining muscle is also warranted.

Our study is further limited by the broad age-range of our sample. Although we accounted for age in our models, and the measures have been used with both early adolescents and high school students in the past, some predictors may be more important for particular age groups than others (e.g., media influences during early adolescence), which would not be illuminated with the current sample. In addition, the pattern of linkages found between risk factors and perceptions of the upper body may be different among younger adolescents and older adolescents whose bodies are more developed. Longitudinal research examining how body perceptions unfold from childhood through early adulthood is ideal.

The study is also limited by the measures—further research is needed to examine the nature of the pressures perceived by adolescents. In-depth qualitative research may help to elucidate how these messages are conveyed to adolescents, whether the pressure is explicit or inferred from behaviors or comments from those close to adolescents. In addition, more information is needed to understand better how different types of media (e.g., reality television shows, fashion magazines) translate into perceived pressures to lose weight or gain muscle for adolescents. More detailed information about the sources of pressure can help us to prevent adolescents from interpreting messages from others as pressure-inducing and decrease the likelihood of increased health risks.

Finally, future research should further examine the roles of different family members in exerting pressure to either lose weight or gain muscle. Past research suggests that while both parents play a role in adolescents’ body and weight-related issues, mothers’ and fathers’ contributions are unique and have differing effects on daughters versus sons (May et al., 2006). Similarly, rather than examine friend influences in general, pressures from same-sex and opposite-sex friends should be identified (Gerner and Wilson, 2005); the latter may exert greater influence due to the connection between appearance and cultural norms of heterosexual dating. Modeling of parents’ dysfunctional eating attitudes and behaviors, and sibling comparison and teasing should also be examined.

Conclusions

Adolescents with a pattern of particularly unhealthy eating attitudes and inappropriate eating behaviors are at a higher risk for eating disorders. The current research suggests that pressures from family and friends to be thin and gain muscle, low parental support, low body esteem, and perceptions that one’s own body is different from ideal are all important predictors of such high- risk eating-related beliefs and behaviors. The developmental context in which adolescents live today tends to be one in which looks are of utmost importance, support is limited, and pressure to live up to the cultural ideals of attractiveness are high. Such a context, unfortunately, does not serve to promote positive youth outcomes. Not only may the low self-esteem associated with this context lead to low body esteem and possibly eating disorders, but adolescents who tend to be appearance-oriented and compare their bodies to peers and images in magazines are also more likely to report risky sexual behavior and substance use (Gillen et al., 2006; Palmqvist and Santavirta, 2006). Increased attention to the pressures that adolescents feel and their desire to be thin or muscular, may help us determine what makes some youth more vulnerable than their peers, enhancing our ability to detect and prevent eating disorders among adolescents—regardless of their gender.

References

Archibald AB, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J (1999) Associations among parent-adolescent relationships, pubertal growth, dieting, and body image in young adolescent girls: a short-term longitudinal study. J Res Adolesc 9(4):395–415

Bearman SK, Presnell K, Martinez E, Stice E (2006) The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc 35(2):229–241

Bryant AL, Zimmerman MA (2002) Examining the effects of academic beliefs and behaviors on changes in substance use among urban adolescents. J Educ Psychol 94(3):621–637

Cafri G, Thompson JK (2004) Measuring male body image: A review of the current methodology. Psychol Men and Masculinity 5:18–29

Cafri G, Thompson JK, Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Smolak L, Yesalis C (2005) Pursuit of the muscular ideal: Physical and psychological consequences and putative risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev 25(2):215–239

Carlson Jones D (2004) Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Dev Psychol 40(5):823–835

Cash TF (1995) Developmental teasing about physical appearance: Retrospective descriptions and relationships with body image. Soc Behav Pers 23(2):123–130

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2006) Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. Surveill Summ, MMWR 55(5):1–107

Dunkley TL, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ (2001) Examination of a model of multiple sociocultural influences on adolescent girls’ body dissatisfaction and dietary restraint. Adolescence 36(142):265–279

Eccles JS (1993) Middle school family survey study. University of Colorado, Boulder

Edelbrook C, Costello AJ, Dulcan M, Kalas R, Conover N (1985) Age differences in the reliability of the psychiatric interview of the child. Child Dev 56:265–275

Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Haines J, Wall M (2006) Weight-teasing and emotional well-being in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT. J Adolesc Health 38(6):675–683

Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor B, Berkey CS, Roberts SB, Colditz GA (2001) Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics 107(1):54–60

Franzoi SL (1994) Further evidence of the reliability and validity of the body-esteem scale. J Clin Psychol 50:237–239

Franzoi SL, Shields SA (1984) The body-esteem scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. J Pers Assess 48:173–178

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9(2):273–279

Gavazzi SM (1994). Perceived social support from family and friends in a clinical sample of adolescents. J Pers Assess 62(3):465–471

Gerner B, Wilson PH (2005) The relationship between friendship factors and adolescent girls’ body image concern, body dissatisfaction, and restrained eating. Int J Eat Disord 37(4):313–320

Gila A, Castro J, Cesena J, Toro J (2005) Anorexia nervosa in male adolescents: Body image, eating attitudes and psychological traits. J Adolesc Health 36:221–226

Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES, Shearer CL (2006) Does body image play a role in risky sexual behavior and attitudes? J Youth Adolesc 35(2):243–255

Grabe S, Hyde JS (2006) Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction among women in the United States. Psychol Bull 32(4):622–640

Griffiths JA, McCabe MP (2000) The influence of significant others on disordered eating and body dissatisfaction among early adolescent girls. Eur Eat Disord Rev 8(4):301–314

Harrison K, Hefner V (2006) Media exposure, current and future body ideals, and disordered eating among preadolescent girls: A longitudinal panel study. J Youth Adolesc 35(2):153–163

Harter S (1982) The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev 53:87–97

Harter S (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. Guilford Press, New York

Jones DC, Crawford JK (2006) The peer appearance culture during adolescence: Gender and body mass variations. J Youth Adolesc 32(2):257–269

Jones DC, Vigfusdottir TH, Lee Y (2004) Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: An examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. J Adolesc Res 19(3):323–339

Keery H, Boutelle K, van den Berg P, Thompson JK (2005) The impact of appearance-related teasing by family members. J Adolesc Health 37(1):120–127

Klaczynski PA, Goold KW, Mudry JJ (2004) Culture, obesity stereotypes, self-esteem, and the “thin ideal”: A social identity perspective. J Youth Adolesc 33(4):307–328

Levine MP, Smolak L (2002) Body image development in adolescence. In Cash TF, Pruzinsky T (eds) Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. Guilford, New York, pp 74–82

Lieberman M, Gauvin L, Bukowski WM, White DR (2001) Interpersonal influence and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls: The role of peer modeling, social reinforcement, and body-related teasing. Eat Behav 2(3):215–236

Littleton HL, Ollendick T (2003) Negative body image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 6(1):51–66

Lombardo C, Russo PM, Lucidi F, Iani L, Violani C (2004) Internal consistency, convergent validity and reliability of a brief Questionnaire on Disordered Eating (DEQ). Eat Weight Disord 9(2):91–98

Ludden AB, Eccles JS (in press) Psychosocial, motivational, and contextual profiles of youth reporting different patterns of substance use during adolescence. J Res Adolesc

May AL, Kim J, McHale SM, Crouter AC (2006) Parent-adolescent relationships and the development of weight concerns from early to late adolescence. Int J Eat Disord 39(8):729–740

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA (2001) Parent, peer, and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence 36(142):225–240

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA (2003) Body image and strategies to lose weight and increase muscle among boys and girls. Health Psychol 22(1):39–46

Mintz LB, O’Halloran MS (2000) The eating attitudes test: Validation with DSM-IV eating disorder criteria. J Pers Assess 74(3):489–503

Nishina A, Ammon NY, Bellmore AD, Graham S (2006) Body dissatisfaction and physical development among ethnic minority adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 35(2):189–201

Palmqvist N, Santavirta N (2006) What friends are for: The relationships between body image, substance use, and peer influence among Finnish adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 35(2):203–217

Paxton SJ (1996) Prevention implications of peer influences on body image dissatisfaction and disturbed eating in adolescent girls. Eat Disord 4(4):334–347

Paxton SJ, Schutz HK, Wertheim EH, Muir SL (1999) Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. J Abnorm Psychol 108(2):255–266

Pendley JS, Bates JE (1996) Mother/daughter agreement on the eating attitudes test and the eating disorder inventory. J Early Adolesc 16(2):179–191

Phares V, Steinberg AR, Thompson JK (2004) Gender differences in peer and parental influences: Body image disturbance, self-worth, and psychological functioning in preadolescent children. J Youth Adolesc 33(5):421–429

Pope HG, Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R (2000) The Adonis complex: How to identify, treat, and prevent body obsession in men and boys. Touchstone, New York

Presnell K, Bearman SK, Stice E (2004). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: A prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 36(4):389–401

Procidano ME, Heller K (1983) Measures of perceived social support from friends and family: Three validation studies. Am J Community Psychol 11:1–24

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2003) Sociocultural and individual influences on muscle gain and weight loss strategies among adolescent boys and girls. Psychol Sch 40(2):209–224

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2004) A biopsychosocial model of disordered eating and the pursuit of muscularity in adolescent boys. Psychol Bull 130(2):179–205

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Banfield S (2000) Body image and body change methods in adolescent boys: Role of parents, friends, and the media. J Psychosom Res 49(3):189–197

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Lillis J, Thomas K (2006) A longitudinal investigation of the development of weight and muscle concerns among preadolescent boys. J Youth Adolesc 32(2):177–187

Rierdan J, Koff E (1997) Weight, weight-related aspects of body image, and depression in early adolescent girls. Adolescence 32(127):615–624

Rieves L, Cash TF (1996) Social developmental factors and women’s body-image attitudes. J Soc Behav Pers 11(1):63–78

Rosen JC, Silberg NT, Gross J (1988) Eating attitudes test and eating disorders inventory: Norms for adolescent girls and boys. J Consult Clin Psychol 56(2):305–308

Schwartz DJ, Phares V, Tantleff-Dunn S, Thompson JK (1999) Body image, psychological functioning, and parental feedback regarding physical appearance. Int J Eat Disord 25(3):339–343

Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R (1999) Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health 25:155–165

Smolak L, Murnen SK, Thompson JK (2005) Sociocultural influences and muscle building in adolescent boys. Psychol Men and Masculinity 6(4):227–239

Stice E, Bearman SK (2001) Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: A growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol 37(5):597–607

Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D (2002) Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: A 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol 21(2):131–138

Stice E, Maxfield J, Wells T (2003) Adverse effects of social pressure to be thin on young women: An experimental investigation of the effects of “fat talk”. Int J Eat Disord 34(1):108–117

Stice E, Whitenton K (2002) Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol 38(5):669–678

Swarr AE, Richards MH (1996) Longitudinal effects of adolescent girls’ pubertal development, perceptions of pubertal timing, and parental relations on eating problems. Dev Psychol 32(4):636–646

Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tantleff-Dunn S (1999b) Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Thompson S, Corwin S, Rogan T, Sargent R (1999a) Body size beliefs and weight concerns among mothers and their adolescent children. J Child Fam Stud 8(1):91–108

Thompson JK, Tantleff S (1992) Female and male ratings of upper torso: Actual, ideal, and stereotypical conceptions. J Soc Behav Pers 7:345–354

Thompson MA, Gray JJ (1995) Development and validation of a new body-image assessment scale. J Pers Assess 64(2):258–269

Tiggemann M (2001) The impact of adolescent girls’ life concerns and leisure activities on body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and self esteem. J Genet Psychol 162(2):133–142

Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Tilgner L (2004) Test-retest reliability and construct validity of Contour Drawing Rating Scale scores in a sample of early adolescent girls. Body Image 1(2):199–205

Weltzin T, Weisensel NE, Franczyk D, Burnett K, Klitz C, Bean P (2005) Eating disorders in men: Update. J Men’s Health Gender 2(2):186–193

Wiseman CV, Peltzman B, Halmi KA, Sunday SR (2004) Risk factors for eating disorders: Surprising similarities between middle school boys and girls. Eat Disord 12(4):315–320

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Rheanna N. Ata is currently a research assistant at the Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center, Miriam Hospital/Brown University. She is interested in body image and eating disorders and completed this research during her undergraduate studies at the College of the Holy Cross.

Alison Bryant Ludden is a developmental psychologist whose research focuses on social relationships and problem behaviors during adolescence, with a special interest in school as a developmental context. She is an assistant professor of psychology at the College of the Holy Cross.

Megan M. Lally is currently a graduate student in psychology at Pepperdine University. She completed this research during her undergraduate studies at the College of the Holy Cross.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ata, R.N., Ludden, A.B. & Lally, M.M. The Effects of Gender and Family, Friend, and Media Influences on Eating Behaviors and Body Image During Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 36, 1024–1037 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x