Abstract

The present study investigated the role of sexist ideology in perceptions of health risks during pregnancy and willingness to intervene on pregnant women’s behavior. Initially, 160 female psychology undergraduates in the South East of England completed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1996). Two months later, in an apparently unrelated study, they rated the safety of 45 behaviours during pregnancy (e.g., drinking alcohol, exercising, drinking tap water, and oral sex), and indicated their willingness to restrict pregnant women’s choices (e.g., by refusing to serve soft cheese or alcohol). As predicted, benevolent (but not hostile) sexism was related to willingness to restrict pregnant women’s choices. This effect was partially mediated by the perception that various behaviors are unsafe during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across cultures and periods of history, taboos and behavioral restrictions have surrounded pregnancy. Recent decades have seen the advent of official health advice given to pregnant women, typically advising against the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and various foods on the grounds of potential harm to unborn children. In this article, we argue that in at least some developed nations, these factors have contributed to a normative climate in which the behavior of pregnant women is construed as potentially unsafe, and in which it is acceptable to act in ways that restrict pregnant women from exercising free choice. Drawing upon Glick and Fiske’s (1996) influential conceptualization of sexism, we also argue that an affectionate but patronising view of women known as benevolent sexism plays an important role in this social phenomenon. We report a study using survey methodology with a sample of English undergraduate women designed to test hypotheses derived from this theoretical perspective.

In 2009, a pregnant woman tried to buy a portion of cheddar cheese from the delicatessen counter of a major English supermarket. Although cheddar cheese poses no particular health risk during pregnancy, a female staff member refused to sell it to her until she promised that she would not eat it herself. “How ridiculous”, said the customer in her letter of complaint, “that I had to openly lie in order to buy a piece of cheese”. She also reported that the staff member “told me how lucky my generation of pregnant women are to have such [health] information available to them because this was not the case ‘in her day’. I could only respond by saying that I thought pregnant women in the past were probably a whole lot less stressed and guilt-ridden as a result” (Clench 2009).

Albeit more vivid and absurd than usual, this woman’s experience illustrates the impingements upon their autonomy that pregnant women are subjected to. This does not happen only in England. In a further case in the same year, a Florida court enforced a bedrest on a pregnant woman that had been advised by her obstetrician (Burton v. Florida 2009). Further instances are found in anecdotes of pregnant women being refused service in English bars or even evicted for sipping from a small glass of beer (Elliot 2009). Also, in the last decade, the Governments of the UK, USA, Canada, France, Australia and New Zealand have stiffened their advice, recommending that women abstain altogether from alcohol. However, even advocates of this advice concede that there is scant evidence that light alcohol consumption (1 or 2 standard units of alcohol once or twice a week) is harmful to the fetus (e.g., Nathanson et al. 2007). Some findings, indeed, suggest there could be a benefit (e.g., Kelly et al. 2008). This discrepancy between evidence and official advice has led some medical researchers and senior practitioners to wonder whether a “value judgement” is being imposed on women without sufficient evidence from medical science (e.g., O’Brien 2007, p. 856).

Whether this paternalistic stance toward pregnant women does indeed have an ideological basis is the most general question that motivates the present investigation. Of course, it is extremely unlikely that such paternalism is driven by ideology alone; like most social phenomena, it is probably determined by many other factors. For example, if indeed public attitudes as well as official advice have recently become more restrictive, we might look to underlying social trends for explanations. Such trends might include the increasing availability of health information, authentic or otherwise, and an increasingly paranoid and aversive attitude to risk (Furedi 2001). It would also be possible, indeed plausible, to view any increase in paternalism as another manifestation of the recent backlash against the freedoms won by feminists in the 1970s (Faludi 1991; Rudman and Fairchild 2004). However, as interesting as these hypotheses about social change may be, it is beyond the scope of the present investigation to test them. Rather, we seek to examine whether willingness to restrict pregnant women’s choices may be informed by long-standing, even ancient, ideologies about gender.

Despite the intuitive appeal of this general hypothesis, it remains almost completely unexamined. Certainly, childbearing women have traditionally been subjected to a range of restrictions based on folkloric medical wisdom and taboo, rather than systematic medical science. For example, women in parts of Europe, Asia and Africa have been subjected to pre- and post-natal confinement, meaning periods of time in which they are not allowed to venture beyond their dwelling (e.g., Gélis 1996; Newman 1969; Rice 2000). Traditionally, pregnant and nursing women have been subjected to dietary exclusions in areas of the world including Mexico (Ninuk 2005) and Indonesia (Santos-Torres and Vasquez-Garibay 2003), at times depriving them of particularly nutritious and beneficial foods such as rice (Meyer-Rochow 2009). Some thinkers have linked these restrictive social practices to the need, in patriarchal social systems, for men to control women’s fertility. For example, Rothman (1994, p. 141) wrote that in such societies, “the essential concept is the ‘seed’, the part of men that grows into the children of their likeness within the bodies of women.... it is women’s motherhood that men must control to maintain patriarchy”. Patriarchal ideology, therefore, is held to require that women’s autonomy during pregnancy be curtailed. Thus far however, this view is not corroborated directly by social psychological theory or evidence.

Despite the lack of direct support for the hypothesis that the placing of restrictions upon pregnant women are ideologically motivated, some findings, considered together, provide indirect support for it. For example, in an influential study of the norms surrounding prejudice, Crandall et al. (2002) asked US college undergraduates the extent to which it is “OK to feel negatively” (p. 362) towards 105 social groups. Only rapists, child abusers, child molesters, wife beaters, terrorists, racists, members of the KKK, drunk drivers, and neo-Nazis were regarded as more legitimate targets of prejudice than the group “Pregnant women who drink alcohol”. It is also clear that these more conventionally odious groups overlap substantially (for example, there is a good chance that members of the KKK are also racist). Arithmetically, prejudice towards these women was regarded as more justifiable than prejudice toward the remaining 95 social groups, which included gang members, drug dealers, adulterers, exam cheats, and negligent parents. This strength of feeling seems to suggest that pregnant women who drink alcohol offend not only social convention and commonsense, but also a widely shared, deep-seated system of values.

Most salient to the ideological basis of the treatment of pregnant women, Hebl et al. (2007) conducted a field experiment in which female confederates posed either as customers, or applicants for jobs, in American retail stores. Confederates posing as job applicants were treated in a more hostile fashion by staff members when they appeared to be pregnant (thanks to a prosthesis) than when they did not. In contrast, confederates posing as customers were treated in a more kind and friendly fashion when they looked pregnant. Hebl et al. reasoned that apparently pregnant women were treated in these different ways because shopping but not working is a socially ordained role for them. This interpretation was reinforced by a second experiment in which pregnant applicants for stereotypically masculine jobs (e.g., janitor, corporate lawyer) as opposed to feminine jobs (e.g., maid, family lawyer) were met with especially hostile responses by members of the public. The studies by Hebl et al. (2007) reveal that the treatment afforded to pregnant women is shaped by whether or not they behave in accordance with traditional conceptions of their role. However, their studies were not designed to test whether beliefs and advice about the health of mother and baby have an ideological basis. Neither did they include a direct measure of ideology.

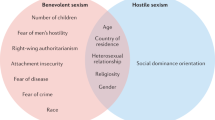

The present investigation is the first to explore the empirical relationship between ideology, beliefs about health risks during pregnancy, and willingness to restrict pregnant women’s freedoms. Of particular interest are sexist ideologies, which are theoretically linked to patriarchal social systems (Rothman 1994; Rudman and Fiske 2008). The most influential social-psychological model of these ideologies was offered by Glick and Fiske (1996). They argued that cultural representations of women are ambivalent. Throughout history and across cultures, “women have been revered as well as reviled” (Glick and Fiske 1996, p. 491). Reverent or benevolent sexism is a pattern of attitudes towards women which characterizes them as special, pure, necessary for men’s happiness, and in need of protection. It is associated with warm feelings and some warm behaviors towards women, but also with a tendency to patronise them, and to see them in stereotypical terms that suggest they are naturally suited to domestic roles. In contrast, hostile sexism is negatively valenced and portrays women as competitive, manipulative, and devious; a threat, rather than a boon, to men.

This model of sexism was extensively validated across cultures by Glick et al. (2000). Although women tend to endorse hostile sexism somewhat less than men do, they endorse benevolent sexism just as strongly. In studies that have included both men and women in their samples, benevolent sexism has had much the same effects on social judgment (Abrams et al. 2003; Glick et al. 2000). Benevolent and hostile sexism are not mutually exclusive and indeed appear to be complementary components of a patriarchal system of ideology which justifies and perpetuates the subordination of women (Glick and Fiske 2001). However, they are distinguishable psychometrically and often have distinct effects on social evaluations (e.g., Abrams et al. 2003; Viki and Abrams 2002). Of particular interest to this article, despite its name and positive affective tone benevolent sexism has adverse consequences for women. It has been shown to be associated with increased appearance-oriented behavior (use of cosmetics) among U.S. female undergraduates (Franzoi 2001), the blame of victims of acquaintance rape among English undergraduates (Abrams et al. 2003), and, when made experimentally salient, to reduce cognitive performance among samples of women in Belgium (Dardenne et al. 2007).

Thus, the present investigation is designed to determine not just whether, but also what type of, sexism is relevant to paternalism toward pregnant women. Are perceptions of risk and the cultural tendency to deny autonomy to pregnant women an artifact of misogyny: a dislike and distrust of women (i.e., hostile sexism)? Or do they follow, ironically, from the affectionate view of women as more communal and in need of protection (i.e., benevolent sexism)? There are interrelated theoretical grounds to suspect that benevolent sexism leads to the perception of dangers to pregnant women, and also to a desire to restrict their choices in a paternalistic fashion.

One is the origin of benevolent sexist ideology. Theorists have linked this to women’s particular reproductive role (Glick and Fiske 1996). Stylized carvings of pregnant women are among the earliest human artworks discovered by archaeologists, showing that they have been revered for at least tens of thousands of years. This reverence is adaptive insofar as an abundance of healthy women is essential for groups striving to grow their population or maintain it in trying circumstances (Guttentag and Secord 1983). Men in patriarchical social systems are especially dependent on women to provide them with male children (e.g., Rothman 1994). The significance of women’s reproductive role for benevolent sexism means that this ideology can be expected to motivate concern for the safety of pregnant women and the children they are carrying.

More generally, and perhaps for the same reason, benevolent sexism is likely to motivate concern for the safety and welfare of women, whether or not they are currently pregnant. It exhorts men to cherish and protect women, and implies therefore that women are vulnerable to harm. Indeed, benevolent sexism has been shown to relate to heightened appraisals of environmental danger, as in the fear of crime (Phelan et al. 2010). This elevated perception of danger tends to result in heterosexual men taking on an “altruistic” fear of crime, in which their principal fear is for the safety of their romantic partner (Rader 2010). The perception of women’s relative weakness or vulnerability also provides a powerful justification to intervene on their behavior. For example, Moya et al. (2007) found that Spanish women (undergraduates and members of their families) higher in benevolent sexism found it more acceptable for husbands to impose prohibitions on wives, so long as these prohibitions appeared to be justified by a protective motivation (e.g., “Don’t you drive; it’ll stress you out”).

On the other hand, although it is clear that hostile sexism is likely to be relevant to the way that pregnant women are treated, especially if they violate traditional norms of behaviour (e.g., Hebl et al. 2007; Sibley and Wilson 2004), it is less likely to be related specifically to a concern with the safety and welfare of pregnant women. It is characterised by an adverse emotional response to women, and perceptions that men and women’s interests are opposed to, or at best independent of, each other. It is therefore unlikely to encourage people to envisage that pregnant women and their children face environmental danger, or to make efforts to protect them.

Aim and Hypotheses of the Present Study

The present study sought to investigate the relationship between hostile and benevolent sexism, perceptions of the safety during pregnancy of a range of behaviours, and willingness to prevent pregnant women from engaging in behaviours that are widely perceived to be risky. In Phase 1 of the study, participants completed a measure of hostile and benevolent sexism. In Phase 2, apparently unrelated and conducted some two months later, participants answered questions about the perceived safety of various behaviours during pregnancy and their willingness to intervene on pregnant women’s choices.

Based on our analysis of the functions and consequences of benevolent and hostile sexism, we made the following key predictions:

-

H1.

Benevolent sexism (but not necessarily hostile sexism) will be negatively related to the perceived safety of pregnant women’s behaviors.

-

H2.

Benevolent sexism (but not necessarily hostile sexism) will be positively related to willingness to intervene on pregnant women’s behavior.

Our theoretical analysis implies that one reason benevolent sexism motivates restrictive interventions may be that it heightens perceptions that pregnant women’s behavior is potentially unsafe. On the other hand, as we have seen, benevolent sexism appears to confer upon others a right to act paternalistically to restrict women’s choices, even when they are not pregnant or facing palpable harm. Therefore, we predicted:

-

H3.

The relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene will be partially mediated by perceived safety.

Finally, in order to conduct a preliminary exploration of the generality of the relation between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene, we examined whether it was moderated by two salient variables. Recent research suggests that people may be more willing to act upon beliefs that they believe to be based on reliable evidence (Petty and Briñol 2008). Thus, we postulated that the relation between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene may be strengthened by perceived knowledge of pregnancy. Second, we reasoned that among participants who view pregnant women’s choices as potentially dangerous, benevolent sexism may be a particularly potent predictor of willingness to intervene (in order to save pregnant women from themselves, as it were). We therefore postulated that the relation between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene would be strengthened by high levels of perceived knowledge. These exploratory hypotheses are encapsulated by the general prediction that:

-

H4.

The relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene will be moderated by perceived knowledge of pregnancy and perceived safety.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were 160 undergraduate psychology students (M = 19.96 years, SD = 4.74) who participated in the study in exchange for course credit. All participants were women; the population of psychology students from which this sample was taken is skewed heavily toward women and was unlikely to yield a sufficient number of men upon which to base robust inferences. The present study employed a correlational, cross-sectional design. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the key predictor variables, hostile and benevolent sexism, were measured some months before the other variables.

Materials and Procedure

In a pre-test session conducted some weeks before the other variables were measured (in late September and early October 2009), and as part of a battery of measures for unrelated studies, participants completed the measure of sexism described below. In the main study, conducted in November and December 2009, participants completed the remaining measures, having been informed that they were participating in a study on perceptions of health risks during pregnancy. The following variables were key to our hypotheses.

Sexism

Participants completed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1996), which contains a subscale of 11 items referring to Hostile Sexism (α = .85, e.g., “Most women fail to appreciate fully all that men do for them”), and 11 items pertaining to Benevolent Sexism (α = .80: e.g., “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess”). Participants responded on a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and the mean of their responses was calculated after some items were reverse scored according to the coding instructions of Glick and Fiske (1996).

Perceived Safety

Given the paucity of research on social-psychological predictors of attitudes to the behaviours of pregnant women, a new scale was constructed for this study. This scale was treated both as mediator and moderator in the analyses. Participants were instructed that “Medical research suggests that some of the following activities are unsafe for pregnant women to engage in, because of health risks to them or their babies. Please indicate which you believe fall into this category.” Participants were then presented with a list of 45 behaviours such as “Travelling abroad”, “Eating hotdogs”, “Having sex”, and “Taking folic acid” and indicated the safety of each behaviour on a scale from 1 “Definitely Unsafe”, 2 “Probably Unsafe”, 3 “Probably Safe” and 4 “Definitely Safe”. These 45 items were adapted from a number of internet sources offering advice to pregnant women (see Appendix for list of items and their sources). Their mean was calculated to provide an index of perceived safety (α = .89).

Willingness to Intervene

In a new scale constructed for this study, participants were then asked to read six scenarios and rate the extent to which they would carry out the behaviour described in the scenario (1 = “Definitely Wouldn’t,” 7 = “Definitely Would”). Scenario examples include “Imagine that you are working on a delicatessen counter in a supermarket. A pregnant woman wants to buy some blue veined cheese. Would you serve her?”, “If you saw a pregnant women doing something you thought was inadvisable (e.g., drinking alcohol, engaging in strenuous activity, eating risky foods) would you say something to her?” An additional question was also added to two of the scenarios to further investigate the exact actions participants may take, and included “Would you offer a cigarette to the pregnant woman?” and “Would you offer her tap water?”. Altogether these 8 items were averaged to comprise the measure of willingness to intervene (α = .69) (See Appendix for full details).

Perceived Knowledge of Pregnancy

Undergraduate students may have, on average, a limited knowledge of pregnancy. It is therefore important to show that findings apply to students with relatively high and low levels of knowledge. To this end, we developed 5 items specifically for this study. The first item was “I know someone who is pregnant at the moment” (41% answered “yes”, 59% “no”). The remaining items read, “I have read books and articles about pregnancy and what pregnant women experience” (M = 3.55, SD = 1.85), “I have studied pregnancy”, (M = 3.21, SD = 1.85) “ I feel I have a good knowledge of pregnancy” (M = 4.00, SD = 1.68) and “I have a good knowledge of what pregnant women are advised to do and to avoid during pregnancy” (M = 4.38, SD = 1.52) (1 = “Not At All”, 7 = “A Great Deal”). Responses to each item were standardized and the mean of these standardized scores comprised the index of perceived knowledge of pregnancy (α = .77).

Results

The means and standard deviations of the test variables and intercorrelations between them are presented in Table 1. We first conducted partial correlations to examine the relationship between benevolent sexism and the perceived safety of pregnant women’s behaviors (H1) and willingness to intervene (H2). We then conducted a set of regression analyses recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test the hypothesis that the relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene would be partially mediated by lower levels of perceived safety (H3). Further, we conducted hierarchical regression analyses also recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test the hypothesis that the relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness would be moderated by perceived safety and perceived knowledge of pregnancy (H4). Finally, we report the results of some auxiliary and exploratory tests of the generality of our findings.

Correlational Analyses Involving Benevolent and Hostile Sexism

As recommended by Glick and Fiske (1996), we tested our first two hypotheses with partial correlation analyses, in which the relationship between each measure of sexism and test variables was examined while controlling statistically for the other measure of sexism. These analyses revealed that as predicted (H1), benevolent sexism (controlling for hostile sexism), was negatively related to perceived safety, r(147) = −.22, p = .006. Also as predicted (H2), benevolent sexism was positively related to willingness to intervene on pregnant women’s behavior, r(147) = .28, p < .001. In further support of these first two hypotheses, hostile sexism was unrelated to perceived safety, r(147) = .08, p = .341, and willingness to intervene, r(147) = −.04, p = .651, when benevolent sexism was controlled for.

Analysis of Mediation

Given that benevolent sexism was related both to health beliefs and paternalism, we proceeded to test the hypothesis (H3) that the relationship between benevolent sexism and paternalistic intervention would be mediated by perceptions of danger (Baron and Kenny 1986). Step 1 of the mediation analysis confirmed that benevolent sexism was related to perceived safety, β = −.23, t = −2.84, p = .005. Step 2 verified that it was also related to willingness to intervene, β = .28, t = 3.66, p < .001. Step 3 showed that perceived safety was strongly related to willingness to intervene when benevolent sexism was controlled for, β = −.48, t = −6.83, p < .001. However, the direct path between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene remained significant, β = .18, t = 2.53, p = .013. A Sobel test supported the hypothesis that there would be partial mediation, z = 2.62, p = .008.

Analysis of Moderation

Hierarchical linear regressions were calculated to determine whether the relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene was qualified by other factors as predicted by H4. We mean-centred benevolent sexism and the potential moderators. In Step 1, we entered them simultaneously as predictors of willingness to intervene, and then in Step 2, we added the interaction term, multiplying benevolent sexism by the moderator. The results are presented in Table 2. As this table shows, neither perceived knowledge of pregnancy nor perceived safety moderated the relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to intervene. Adding interaction terms including these variables did not contribute to the models’ ability to account for variation in willingness to intervene. Neither were these interaction terms significant predictors of willingness to intervene. Finally, of the two potential moderators we considered, only perceived safety was related to willingness to intervene. In summary, we found no support for H4. Note that the results of regression analyses reported in this article were not affected by collinearity between predictors. Diagnostic tests revealed in all cases that tolerance was >.90, well above the range <.20 that is conventionally defined as problematic.

Additional Exploratory Analyses

Although not initially hypothesized, we conducted some exploratory tests of the generality of our effects that we considered may be of interest to further theory and research. First, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the relationship between both measures of sexism and the perceived safety of each of the 45 behaviors in our list. Significant results are presented in Table 3. These represent a diverse range of behaviours, including dietary, lifestyle, and sexual behaviours. Some of these behaviours are proscribed by official advice (e.g., sleeping on your back), but the majority are not (e.g., having sex, having oral sex, using a microwave), and one is positively good for pregnant women (e.g., exercising at all). Further, in addition to the moderation analyses reported in Table 2, we determined that participants’ perceived knowledge of pregnancy did not moderate the relationship between benevolent sexism and perceived safety. The interaction term (mean-centred benevolent sexism multiplied by perceived knowledge) was not a significant predictor of perceived safety, β = .053, t = .66, p = .509, and adding it did not increase explained variance in perceived safety, F(1, 150) = 1.45, p = .509, R 2 = .00.

Discussion

The present study was the first to examine the link between sexist ideologies and perceptions of risk during pregnancy, and willingness to intervene on those risks by restricting pregnant women’s choices. Results uncovered a positive relationship between benevolent sexism and perceptions of risk. Largely independent of this effect, benevolent sexism also predicted participants’ self-reported willingness to act to obstruct pregnant women from doing things that are widely perceived to present a health risk. The present results therefore implicate sexist ideology as a contributor to lay people’s health concerns regarding pregnant women, and their willingness to restrict the freedom of pregnant women.

More specifically, the present findings illustrate the utility of distinguishing between benevolent and hostile forms of sexism. Hostile sexism, referring to misogynistic antipathy toward women, did not appear to play an active role in this study. Rather, benevolent sexism appeared to be the active ingredient in perceptions of risk and willingness to restrict pregnant women’s choices. This result is consistent with contemporary theories of the origin and function of this subjectively warm but patronising variety of sexism (Glick and Fiske 1996). According to these theories, benevolence is afforded to women because of the importance of their welfare to the reproductive success of their male partners (e.g., Rothman 1994), or of the community as a whole (e.g., Guttentag and Secord 1983). This underlying ideological motivation for benevolence toward women is likely to predispose individuals to perceive that pregnant women could easily come to harm, and to spur efforts to prevent such harms, even by preventing women from exercising free choice.

The present study therefore makes two key contributions to the social scientific understanding of the perception and treatment of pregnant women. First, it corroborates the suspicion by some (e.g., O’Brien 2007) that restrictive practices regarding pregnant women may have an ideological basis. Second, it illustrates the ability of contemporary approaches to sexist ideology, most notably the theory of ambivalent sexism (Glick and Fiske 1996), to shed light on this social phenomenon. These contributions are promising bases for further research. The remainder of the present discussion focuses on specific directions that future research could take, in light of both the promise and the limitations of this first study.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

An obvious limitation of this study is its reliance on an opportunity sample of women studying undergraduate-level psychology at an English university. One drawback of this sampling from this demographic is that participants are likely to tend to have relatively low levels of personal experience of pregnancy, and relatively few opportunities to intervene on pregnant women’s behavior. Nonetheless, most of our sample are likely to be pregnant themselves within the next decade or two, and the present study can be seen as a useful snapshot of the baseline attitudes that they are likely to take into this life experience. The present sample may also be seen to represent sections of the community that may be described as bystanders—without a great deal of knowledge or personal interest, but ready to provide an ideologically motivated opinion.

It is also encouraging that participants’ perceptions of their own knowledge and of the dangers inherent in various behaviors did not moderate the relationship between benevolent sexism and willingness to interfere with pregnant women’s choices. Although levels of benevolent sexism, knowledge of pregnancy, and willingness to intervene may be different in other populations, it is not yet clear why the relationships between them should be different. Nonetheless, it is clearly desirable to replicate the present results with more representative community samples. Further, the present results need to be replicated in other cultural settings before any claim of cross-cultural generality can be made. Although the theoretical framework of ambivalent sexism has been validated across cultures, we can expect variation at least in the form and possibly in the extent of the specific health belief and taboos surrounding pregnancy, and in people’s willingness to intervene.

It would also be highly desirable to replicate the present results with more specialized samples, such as pregnant women, their friends and families, health professionals, and health officials. We cannot yet confidently extrapolate from the present findings to these populations. However, if sexist ideology is indeed relevant to their attitudes toward health risks in pregnancy, we would expect to observe extremely important functional consequences in each population. Hypothetically, we might expect benevolent sexism to incline pregnant women to restrict their own choices, and possibly, to experience guilt for taking perceived risks with their own welfare or that of the developing fetus (Schaffir 2007). Benevolent sexism may likewise predispose pregnant women’s families, friends and spouses to offer prohibitive advice and to subtly restrict their choices. Benevolent sexism may also motivate health professionals to offer restrictive advice to their pregnant patients, and health officials to formulate prohibitive policies and communiqués (cf. O’Brien 2007).

The use of other dependent measures may also reveal that hostile sexism has some role to play in the treatment of pregnant women. Women who violate conventional expectations often find themselves at the receiving end of this ideology, and an associated stock of responses (e.g., Hebl et al. 2007; Sibley and Wilson 2004). So, we may expect hostile sexism, and not necessarily benevolent sexism, to be related to derogatory and punitive responses to pregnant women who defy conventional restrictions on their behavior. These sorts of responses were not assessed in the present study, which confined itself to perceptions of risk and willingness to prevent women from engaging in conventionally inappropriate actions in the first place.

The fact that these dependent measures were partially independent of each other also suggests a new set of outcomes on which further research might focus. Specifically, benevolent sexism motivated intentions to intervene paternalistically on pregnant women somewhat independently of its association with elevated perceptions of risk. Therefore, something in addition to perceived risk motivates benevolent sexists to intervene on pregnant women’s choices. One possibility is that benevolent sexists believe that pregnant women should live according to a precautionary principle, where women should abstain from behaviors that present a merely suggested risk, no matter how small or implausible. Another possibility is that because benevolent sexism is associated with concerns with women’s purity (Glick and Fiske 1996), it may motivate people to prevent them from subjectively impure or disgusting behaviors, regardless of their perceived health risks. Preventing women from drinking alcohol, tap water, or eating fungus-riddled cheese may satisfy this concern for purity, independently of perceived health risks.

Finally, we suggest that further research should examine some boundary conditions of our findings. First, the present study did not include a non-pregnant control condition. Conceivably, benevolent sexism affects reactions to pregnant women because and only because it affects reactions to women generally. From an applied point of view, this may not matter, but it is a theoretically important question. Arguably, pregnancy provides an opportunity and a justification to restrict women’s choices in ways that would normally be unacceptable, at least in modern Western nations. Thus, pregnancy may be a legitimizing condition (cf. Crandall et al. 2002) enabling ideologies to find expression. Additionally, it is possible that benevolent sexism and related ideological concerns are activated by contact with pregnant women (Rudman and Fiske 2008).

Finally, further research is needed to examine whether benevolent sexism motivates men, as well as women, to intervene on pregnant women’s behavior. Past research does not suggest that gender moderates the effect of benevolent sexism (e.g., Abrams et al. 2003; Sibley and Wilson 2004). However, men may feel less entitled to intervene on women’s behavior, for fear of being perceived as sexist (cf. Sutton et al. 2006), or of contributing to the gender inequality whose existence they sometimes acknowledge exists (Sutton et al. 2008).

In the meantime, the results that our sample of women have yielded show at least that benevolent sexism does not motivates only men to restrict women’s choices. Traditionally, benevolent sexism is thought to disempower women by granting men the power of paternalistic protection over women (Glick and Fiske 1996; Moya et al. 2007). Systems of social control, however, are generally more effective when they are internalized by their targets. Benevolent sexism has been shown at least in North American samples to be appealing to women (Fischer 2006; Kilianski and Rudman 1998). Women’s endorsement of benevolent sexism has been shown to increase in response to awareness of men’s hostility to women, suggesting that it is a strategy that women may use to protect themselves from realistic and material threats posed by men (Fischer 2006; see also Expósito et al. 2010). The appeal of benevolent sexism to women, and their occasional participation in the restrictions that it imposes on their gender arguably illustrate the principle that “when it comes to maintaining social inequality, honey is typically more effective than vinegar” (Jost and Kay 2005, p. 504). On this note, it is striking that in the anecdotes we mentioned at the beginning of this article, the retailer, obstetrician, and the duty bar manager who acted paternalistically were themselves women.

Conclusion

Medical science has shown some behaviors to be risky during pregnancy. There are reasons other than ideology to intervene on the behavior of pregnant women. However, concerns should be raised when sexist ideology is shown to be implicated in the perception of risks during pregnancy, and especially, in willingness to restrict pregnant women’s freedoms. A specific concern is that impositions may be placed on pregnant women, by lay people and possibly by some professionals, that are not warranted by medical knowledge. Indeed, it is striking that even independent of their own medical beliefs, benevolent sexists were willing to deprive pregnant women of choice. Further research is urgently required to investigate the generality of this phenomenon, and its medical, social, and psychological consequences for pregnant women.

Notes

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 111–125. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Burton v. State of Florida, L. T. CA 1167 (Fla. Dist. App. Ct., 1st Dist, 2009).

Clench, J. (2009, October 5). Pregnant mum in cheddar sale ban. The Sun, p. 35. http://www.thesun.co.uk/.

Crandall, C. S., Eshleman, A., & O’Brien, L. (2002). Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: The struggle for internalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 359–378. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.359.

Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 764–779. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.764.

Elliot, E. (2009, March 31). Pregnant women told to leave Hove pub. The Argus p. 1. http://theargus.co.uk/.

Expósito, F., Herrera, M. C., & Moya, M. (2010). Don’t rock the boat: Women’s benevolent sexism predicts fears of marital violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 36–42. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01539.x.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

Fischer, A. R. (2006). Women’s benevolent sexism as reaction to hostility. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 410–416. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00316.x.

Franzoi, S. L. (2001). Is female body esteem shaped by benevolent sexism? Sex Roles, 44, 177–188. doi:10.1023/A:1010903003521.

Furedi, F. (2001). Paranoid parenting. London: Allen Lane.

Gélis, J. (1996). History of childbirth: Fertility, pregnancy and birth in Early Modern Europe. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., Glick, P., Singletary, S. L., & Kazama, S. (2007). Hostile and benevolent reactions toward pregnant women: Complementary interpersonal punishments and rewards that maintain traditional roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1499–1511. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1499.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498.

Kelly, Y., Sacker, A., Gray, R., Kelly, J., Wolke, D., & Quigley, M. A. (2008). Light drinking in pregnancy, a risk for behavioural problems and cognitive deficits at 3 years of age? International Journal of Epidemiology, 2008, 1–12. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn230.

Kilianski, S. E., & Rudman, L. A. (1998). Wanting it both ways: Do women approve of benevolent sexism? Sex Roles, 39, 333–352. doi:10.1023/A:1018814924402.

Meyer-Rochow, V. B. (2009). Food taboos: Their origins and purposes. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 5, 18–27. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-18.

Moya, M., Glick, P., Exposito, F., de Lemus, S., & Hart, J. (2007). It’s for your own good: Benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1421–1434. doi:10.1177/0146167207304790.

Nathanson, V., Jayesinghe, N., & Roycroft, G. (2007). Is it all right for women to drink small amounts of alcohol in pregnancy? No. British Medical Journal, 335, 857. doi:10.1097/01.aoa.0000319773.76362.59.

Newman, L. F. (1969). Folklore of pregnancy: Wives’ tales in Contra Costa County, California. Western Folklore, 28, 112–135.

Ninuk, T. (2005). The importance of eating rice: Changing food habits among pregnant Indonesian women during economic crisis. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 199–210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.043.

O’Brien, P. (2007). Is it all right for women to drink small amounts of alcohol in pregnancy? Yes. British Medical Journal, 335, 856. doi:10.1136/bmj.39371.381308.AD.

Petty, R. E., & Briñol, P. (2008). Persuasion: From single to multiple to metacognitive processes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 137–147. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00071.x.

Phelan, J. E., Sanchez, D. T., & Broccoli, T. L. (2010). The danger in sexism: The links among fear of crime, benevolent sexism, and well-being. Sex Roles, 62, 35–47. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9711-8.

Rader, N. E. (2010). Till death do us part? Husband perceptions and responses to fear of crime. Deviant Behavior, 31, 33–59. doi:10.1080/01639620902854704.

Rice, P. L. (2000). Nyo dua hli—30 days confinement: Traditions and changed childbearing beliefs and practices among Hmong women in Australia. Midwifery, 16, 22–34. doi:10.1054/midw.1999.0180.

Rothman, B. K. (1994). Beyond mothers and fathers: Ideology in a patriarchal society. In E. N. Glenn, G. Chang, & L. R. Forcey (Eds.), Mothering: Ideology, experience, and agency (pp. 139–158). New York: Routledge.

Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, L. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 157–176. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.157.

Rudman, L. A., & Fiske, S. T. (2008). The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. New York: Guilford.

Santos-Torres, M. I., & Vasquez-Garibay, E. (2003). Food taboos among nursing mothers from Mexico. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition, 21, 142–149.

Schaffir, J. (2007). Do patients associate adverse pregnancy outcomes with folkloric beliefs? Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 10, 301–304. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0201-0.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-0718-x.

Sutton, R. M., Douglas, K. M., Wilkin, K., Elder, T. J., Cole, J. M., & Stathi, S. (2008). Justice for whom, exactly? Beliefs in justice for the self and various others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 528–541. doi:10.1177/0146167207312526.

Sutton, R. M., Elder, T. J., & Douglas, K. M. (2006). Reactions to criticism of outgroups: Social convention in the Intergroup Sensitivity Effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 563–575. doi:10.1177/0146167205282992.

Viki, G. T., & Abrams, D. (2002). But she was unfaithful: Benevolent sexism and reactions to rape victims who violate traditional gender role expectations. Sex Roles, 47, 289–293. doi:10.1023/A:1021342912248.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by The Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant 000-22-2540 awarded to Robbie M. Sutton and Karen M. Douglas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Perceived Safety Items

Having your hair dyed or permedFootnote 1, Eating uncooked meatFootnote 2, Going jet skiingFootnote 3, Riding on rollercoastersFootnote 4, Having your teeth whitenedFootnote 5, Travelling abroad2, Having oral sexFootnote 6, Eating for twoFootnote 7, Eating eggs7, Using tanning bedsFootnote 8, Cleaning out cat litter boxes2, Using a microwave2, Getting a tattoo or piercingFootnote 9, Eating hotdogs2, Having a manicure or pedicureFootnote 10, Using a laptop on your lap3, Lifting heavy objects3, Eating starchy foods7, Having contact with reptiles2, Eating fish2, Using an electric blanket2, Sleeping on a water bed2, Using cleaning products or household paints2, Eating foods rich in calcium7, Having contact with pesticides2, Having sex6, Eating ready meals7, Sleeping on your sideFootnote 11, Having X rays2, Taking over the counter medication2, Drinking herbal tea10, Eating or drinking artificial sweeteners10, Eating pate or other foods high in Vitamin A7, Getting stressed2, Eating junk food2, Sleeping on your back11, Getting regular medical examinations2, Exercising at all2, Taking folic acid2, Using a sauna, hot tub or taking long hot baths2, Taking prenatal vitamins2, Travelling to developing countriesFootnote 12, Eating meat at barbecues7, Having house plants2, Eating fat2.

Willingness To Intervene Scenarios And Items

-

*1.

Imagine that you are working on a delicatessen counter in a supermarket. A pregnant woman wants to buy some blue veined cheese. Would you serve her?

-

*2.

Imagine that you are at a party with a pregnant woman. Would you offer her alcohol?

-

*3.

Would you offer a cigarette to the pregnant woman?

-

*4.

Imagine that at work, you are in charge of providing refreshments for yourself and your colleagues. One of your colleagues is pregnant. Would you offer her tea or coffee?

-

*5.

Would you offer her tap water?

-

*6.

Imagine that you are working at a gym and a pregnant woman enters the gym ready to work out. Would you allow her to work out in the gym?

-

*7.

Imagine that you are working at a restaurant and a pregnant woman orders a meal with seafood in it. Would you take the order?

-

8.

If you saw a pregnant woman doing something that you thought was inadvisable (e.g., drinking alcohol, engaging in strenuous physical activity, eating risky foods) would you say something to her?

*reverse-scored

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sutton, R.M., Douglas, K.M. & McClellan, L.M. Benevolent Sexism, Perceived Health Risks, and the Inclination to Restrict Pregnant Women’s Freedoms. Sex Roles 65, 596–605 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9869-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9869-0